Abstract

In academic research on private R&D investments, sectoral differences are generally analyzed on the basis of firms’ classification according to systems such as the American NAICS and the European NACE industry classification systems. The same classification principles are applied in many countries and regions when aggregating R&D statistics to the level of industries, for example by the EU’s statistical office Eurostat. We report evidence suggesting that the share of R&D associated with development of service-oriented products or with service activities is systematically lower than the share of R&D conducted by service sector firms. Results from a survey run in Sweden shows that the revenue streams in a significant share of R&D-performing service sector firms (as classified according to NACE) are dominated by sales of physical products (e.g. factoryless goods producers). An even larger share report that a majority of their R&D is directed towards development of physical products rather than service products (e.g. consultancy companies acting as external R&D departments for their clients in manufacturing industries). These findings imply that the share of R&D investments focusing on service-oriented activities is even lower than traditional statistics suggest.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Understanding and measuring service-oriented R&D efforts

Firms’ willingness to engage in research and development (R&D) activities remains an important concern for economists and policy makers. Historically, the interest in R&D was linked almost entirely to the production and sales of physical goods, which was seen as the productive core of an economy. As a key to inventing new physical products and to improving the efficiency with which they can be produced, R&D activities over time came into increasing focus, e.g. through the decisive role for economic growth that such activities was assigned in the so called new growth theory (e.g. Romer 1990).

Researchers and public authorities consequently have dedicated much effort to collecting data on R&D investments and R&D activities. With services playing an ever bigger role in modern economies, it is natural that such data collection efforts nowadays are broadened to also cover R&D efforts oriented towards service development. Official statistics suggest that the service sector has substantially increased its share of private R&D expenditure throughout the 1980s and 1990s. This development is particularly striking in the United States, where the share of R&D attributed to the service sector increased from below 5% to almost 40% in two decades (Howells 2008).

National statistic agencies have over time altered their methodology for collecting data on R&D by including a broader set of sectors (as defined by firms’ sectoral classification codes) (Jankowski 2001; Gallaher and Petrusa 2006), and surveying methods have been altered to capture service-oriented R&D efforts. These efforts are, however, associated with significant challenges.

A first such challenge is conceptual. Not only are service development activities intimately linked to “regular” business activities, the goals and outcomes of service-oriented R&D are also vaguely defined. Despite considerable effort, scholars still struggle with finding adequate representations of innovation in services (Vang and Zellner 2005). It is hence also very difficult to define and measure sources and effects of innovation in services. While some firms dedicate formal R&D efforts to service development (Love et al. 2010), other firms seem to be able to perform well in service innovation without such efforts (Tether and Tajar 2008b). As pointed out by Tether (2005), innovation in services is linked to the development of new workforce skills, service bundling and to new forms of inter-organizational cooperation. Even if firms make focused efforts to develop their service offering, such efforts might not, even for insiders, be distinguishable from other activities (Coombs and Miles 2000) and hence not easily discernable to outside observers (Djellal et al. 2003; Trigo 2013). In consequence, it is inherently challenging to capture the full extent of firms’ efforts directed towards service innovation through modification of the R&D surveys which—along with data on patenting activity—have been the work-horse of studies of industrial R&D (see e.g. Adams 2005). Self-reported information on R&D related to tax incentives are in many countries biased by technologically oriented definitions of what forms of activities that are considered to be a valid basis for tax deduction (Miles 2007).

Another challenge is one of attribution. In many twenty-first century value chains, services and physical products are intimately entangled. Through servitization of industry, outsourcing of manufacturing as well as services and increased networking when performing R&D, the industrial classification of a firm reporting R&D activities become an increasingly inappropriate indication of to what extend R&D is to be understood as related to the development of physical products or to services, respectively (Jankowski 2001).

In summary, there are substantial inherent methodological challenges of properly capturing R&D expenses directed at development of new and improved services; both because service development activities are difficult to separate from other activities and because of the continuous blurring of boundaries between service and manufacturing sectors through processes of outsourcing and of servitization. In consequence, estimates about the volume of non-manufacturing R&D remain filled with uncertainty.

In this research note, we investigate a particular form of attribution problem. The leading principle by which todays reported R&D expenditures are allocated to physical products and service activities, respectively, is that of using the firm’s industry classification code. Utilizing survey-based data on Swedish firms, we compare this methodology to alternatives based on self-reported information about sales and about the purpose of R&D. We find that attribution based on NACE-codes underestimates the share of R&D expenditure and—in particular—the share of R&D investment which is associated with physical products and manufacturing activities. This finding implies that the share of R&D activity which is associated with truly service-oriented firms is even lower than what most available statistical evidence would seem to suggest. In addition, the R&D activities reported by actual service-oriented firms are to a large extent directed towards developing physical products. One possible explanation to the latter is that consultancy companies, with revenue streams mainly from services, can act as external R&D departments for clients in manufacturing industries (Tether and Tajar 2008b).

2 Industry classification as a basis for R&D analysis

In research efforts seeking to associate private R&D expenditures with different kinds of economic activity, the most commonly used approach is to sort firms with positive R&D expenditures into groups by their main industrial classification (according to the American NAICS, the European NACE or the international ISIC systems). This approach is used e.g. in the Swedish survey on business R&D. Service-sector R&D, by the principle of this and similar surveys, is the sum of all R&D expenditure in firms with a main NACE code identifying them as belonging to the service sector.

In contrast, the US BRDI survey (in its longer form) allocates R&D across sectors by the purpose of R&D rather than the main activity of the R&D-performing firm. In this survey, which has been in use since 2008, firms are asked to attribute their R&D activities directly to economic activities by NAICS code. Data is aggregated into sectors on the principle that all R&D expenditures of a firm are associated with the sector in which expenditures are the greatest. Similar to aggregation by firm-level NACE-code, this aggregation method can be argued to distort the statistical distribution between manufacturing and non-manufacturing activities—in particular for multi-division firms (Awuku-Budu and Sveikauskas 2015). However, it would seem to allow greater precision than the principle of attributing R&D entirely by firms’ main classification.

It is a well-known fact that existing classification schemes—or, more generally, any attempt to produce categories of commercial activities—is liable to problems of imprecision and direct misclassification.Footnote 1 Attempts to quantify the bias introduced in academic research by classification imprecisions are few and far between. Generally, where such studies have been conducted, they tend to confirm an intermediary level of uncertainty in and between leading classification schemes. Kahle and Walkling (1996) finds that the classification of firms (2-digit code) differ between two well-known firm-level databases for well over a third of all firms. Bhojraj et al. (2003) compare four different industry classification systems and find that the across an array of firm-level economic variables, the Global Industry Classifications Standard (GICS) has greater predictive power than both the NAICS and its predecessor the SIC. Among other findings, they report that the GICS classification explains 64% of the firm-level variation in R&D intensity, whereas NAICS explains 52%. Christensen (2013) compared classification by the NACE scheme as implemented in Denmark to self-reported accounts of firms’ activities. He concludes that 18% of the firms in his sample seem misclassified, in the sense that the main 2-digit NACE codes do not correspond to such independently provided information.

The inherent ambiguities and imprecisions of industry classification systems spill over to any attempt to associate R&D expenditure with different economic activities, such as determining to what extent R&D is associated with the development of physical products and manufacturing or service-oriented activities. For example, an inspection of R&D in the US retail sector found that the lion’s part of R&D-performing firms classified as retailers may well have a primary business of manufacturing physical products (NSF 2005). It has also been acknowledged that there is a large group of “factoryless goods producers”, employing about 2 million US workers, which design and coordinate the production of physical goods without running manufacturing operations of their own. (Bernard and Fort 2015). These firms are typically classified as being active in wholesale trade. This implies that substantial R&D efforts directed towards the development of physical goods—such as e.g. the fabled iPhone of Apple Inc.—takes place in firms classified as belonging to the service (i.e. non-manufacturing) sector. Currently, statistical offices are considering the possibility to identify such firms and integrate them into the manufacturing sector of national statistics where appropriate.

Similar classification problems are likely to arise across a wide range of firms and industries (Leiponen and Drejer 2007; Tether and Tajar 2008a). We may for example think about the problems of attributing R&D performed by conglomerate or highly diversified firms to one specific sector, or of the problem of classifying firms driving fast-paced industrial change and innovation—activities which by their very nature challenge existing categorizations (Graham et al. 2007; Hicks 2011). Incoherencies between group-level and firm-level classification may also be a source of measurement inaccuracy. Gallaher et al. (2006) claim that a substantial share of R&D carried out in firms classified as belonging to the financial industry has nothing to do with financial services. This is a statistical artefact which is created by the choice of several large pharmaceutical groups to organize part of their R&D and patenting activities under group holding companies.

Several studies discussing firms’ investments in innovation activities have offered principles for clustering firms that either replace or extend the traditional grouping based on industrial classification codes. Such groupings are often based on business logic (e.g. Pavitt et al. 1989; Evangelista 2000) and mainly complement firm groupings based on NAICS/NACE classes with other principles for aggregating individual NAICS/NACE codes into groups. Hollenstein (2003) presents a grouping based on “innovation modes”. Classifying firms into five groups based on survey data on innovation investments and innovation results, Hollenstein finds a great variety in terms of industry classifications within groups.

As a consequence of the imprecisions and classification difficulties outlined above, aggregate statistics on to what extent service-oriented firms conduct R&D may be biased. This bias may, however, work in two directions, leading to either underestimated or inflated statistics on service R&D. The direction as well as the level of bias hence remains an empirical question. In order to investigate this question, we exploit data that allows us to compare classification by the official industry classification code with alternative definitions of what constitutes a service-oriented firm.

3 Methodology

Data was collected through a survey, developed on the basis of the official Swedish R&D survey. This survey is administered biannually. It is mandatory to respond. All firms with more than 200 employees and all firms classified as having R&D services as their main activity are selected for inclusion, along with a random sampling among all other firms with at least 10 employees, stratified on size and industry. The survey adopts the OECD Frascati manual definition of R&D, thereby aligning itself with definitions currently used e.g. in the US Business R&D and Innovation Survey (BRDIS) and the European Eurostat standard. Specifically, R&D activities are defined as systematic efforts to (1) search for new knowledge or new ideas with or without targeting a particular application or to (2) exploit research results, scientific knowledge or new ideas to develop new materials, goods, services, processes, systems, methods or substantial improvements of existing items in any of these categories.Footnote 2

To the official survey on R&D activities in the year 2011, a small set of additional voluntary questions on firm was appended at the initiative of the authors. One of these questions asked firms to assess what shares of their revenues that during this year were derived from (a) the sales of goods; (b) the sales of services; (c) licensing revenues; and (d) other sources. Our survey also includes questions about the relative importance of service products in terms of the motivation for R&D activities.Footnote 3

Complete answers to the survey were provided by 6951 firms, representing a 92% response rate. 1006 of these firms also completed the voluntary questions, representing a response rate of 13%. Survey weights were constructed for both sets of responses. In the results that follow, these weights are applied in order to allow scaling results up to the level of the Swedish economy.

Data from the survey is matched to register data on the firm’s industry classification. In the analysis that follows, we follow the recommendations of Eurostat, and the European NACE and SPIN classification systems (2007 editions) in defining service industries and service products. In the two-digit version of each of these two systems, codes 01–09 are primary industries, 10–34 are manufacturing industries and 35–99 are reserved for a wide variety of service industries.

4 Results

In a first step, we investigate survey responses on sales and motivation for R&D. In particular, we are interested in how they vary between firms classified as belonging to the service sector—as identified through their NACE code—and other firms. Table 1 shows the share of revenues and the share of R&D expenditure associated with service products in the average firm. In columns 1 and 2, results are broken down by firm classification, according to the NACE system. We observe (column 2) that firms with a NACE-code classifying them as belonging to the manufacturing sector on average report to have less than one-fifth of revenues generated through service sales. They also have a very limited share of R&D motivated by service development. Firms with a NACE-code classifying them as belonging to the service sector are involved in the sales of physical goods to a fairly high degree (on average above one-fourth of revenues are generated from the sales of goods). Notably, a full 40% of R&D at the average service sector firm is motivated by the development of physical products.

Table 1 suggests that it would be inaccurate to associate all R&D conducted in service sector firms with service development activities. In Table 2, we investigate just how large the difference between service sector R&D and service-oriented R&D might be at the level of the aggregate Swedish economy. We find that 20.3% of all R&D expenditures in Sweden are motivated by service development. This is notably less than the share of R&D expenditures accounted for by service sector firms (27.7%).Footnote 4 That is, allocating R&D investment between service and manufacturing activities on the basis of firms’ industry classification codes would seem to substantially overestimate to what extent R&D activities are related to service development.Footnote 5,Footnote 6

In what follows, we present a closer examination of R&D investments and R&D expenditures in the Swedish private sector. In particular, we contrast the service sector given by the use of NACE codes with service-oriented firms defined through self-reported survey information.

The reference point is the traditional division of firms into groups of sectors by main activity, as implemented in industry classification code schemas.

-

A. Classification based on NACE-code Firms are classified as belonging to either a service sector or to a manufacturing sector.Footnote 7

We use the survey questions on revenue streams and on the objective of R&D activities to introduce two definitions of what constitutes a service-oriented firm.

-

B. Classification based on the share of sales derived from services Firms with more than 50% of their operating revenuesFootnote 8 coming from services and/or licensing are classified as service providers. Firms with a majority of revenues from sales of physical goods are referred to as goods providers.

-

C. Classification based on self-reported R&D objectives Firms whose R&D to more than 50% is motivated by service development (SPIN-codes 35–99) are classified as service developers. Firms with R&D expenditures primarily motivated by the development of physical goods are referred to as goods developers.

In consistence with the results presented above, a significant number of firms belonging to service sector industries are goods providers and/or goods developers. This would, for example, apply to “factoryless goods producers”. There are also, however, examples of the opposite relationship, e.g. that firms which report to derive more than 50% of their operating revenues from sales of services have NACE codes identifying them as a manufacturers. We may think of such firms as “highly servitized manufacturers”. We also find three major groups of manufacturing sector firms which are goods producers but also service developers—i.e. a majority of their R&D is directed towards services. These are first and foremost firms from a wide variety of manufacturing NACE codes providing R&D services to other firms. Secondly, there is a group of firms in industries such as graphical production and manufacturing of advanced instruments whose R&D is related to ICT services. Thirdly, a group of firms classified as producers of construction materials are pursuing R&D related to construction services. This latter finding echoes that of Christensen (2013), who find that the difference between NACE codes and firms’ self-reported accounts of their activities to be particularly accentuated among firms classified as belonging to the construction industry.

Table 3 shows breakdowns of Swedish private sector R&D expenditure (i.e. costs for R&D activities conducted within the firm) by each of the three alternative categorizations introduced above. Consistent with the results in Tables 1 and 2, the share of R&D associated with service-sector firms is found to be higher than that associated with either service providers or service developers. The choice of what measure to use as indicator for the degree of servitization of R&D does in light of these findings seem to matter rather substantially. For example, the choice of Swedish official statistics to report the R&D expenditure share of service-sector firms rather than (as in the official US statistics) service developers would seem to partly conceal the prevailingly strong connection to physical goods production in Swedish private sector R&D.

The primary focus of R&D statistics in most countries is on intramural R&D expenditures—as reported in Table 3. This focus on the question of who conducts R&D is motivated e.g. by the view of R&D activities as a source for spatial knowledge spillovers (Audretsch and Feldman 1996). For the purpose of analyzing to what extent R&D is driven by development of service products or physical products, respectively, it is however also interesting to study who is paying for the privately funded R&D. Table 4 reports results on R&D investment, i.e. the level of funding for R&D by firms irrespectively of whether this R&D is conducted intramural or extramurally.Footnote 9

Parallel to the results in Table 3, the share of R&D expenditure associated with service-oriented firms declines when considering alternative definitions to that offered by the NACE-based classification. The difference between service-sector firms and service developers is, in fact, yet more accentuated in Table 4 than in Table 3. This difference is driven by the behavior of a set of firms which are net funders of R&D. On closer examination, it appears that these are firms acting as R&D centers within larger, manufacturing-oriented international groups.Footnote 10

Taken together, the dominant pattern that emerges from our data is that classification by NACE overestimates the importance of services in aggregate accounts of R&D expenditures and—in particular—R&D investment.

In a final set of analysis, we explore to what extent the level of mismatch between industry classification, sales and R&D objectives in terms of firms’ service-orientation is captured by traditional firm-level variables, as commonly used in studies of R&D and innovation. For this analysis, we exploit a connection between our survey data and Swedish official firm registers.

We find that firms which are miss-classified in the sense that they are coded as belonging to a service industry, but which do not meet one of the two alternative criteria for service orientation, are largely similar to other service-industry firms. There are no statistical significant differences in firm size, value added or the growth of turnover in the period 2007–2011. They are also neither less nor more likely to be part of a group or to have foreign ownership. However, miss-classified firms are on average older, have higher turnover per employee, and they are more likely to export. These characteristics seem to fit well with more capital-intensive production. “Miss-classified” firms are found throughout the spectrum of NACE-codes, with particular concentration in ICT and R&D services.

We finally investigate the characteristics of firms whose R&D is motivated by physical product development, despite being classified as service companies. Such firms are roughly twice as R&D intensive as an average R&D-performing service industry firm. The business idea in some of those companies is to do commissioned R&D for clients in the manufacturing industry.

5 Discussion

The provision and effects of R&D for firms, nations and societies remains a central interest for economists (Tassey 2004; Broström and Karlsson 2017). Students of economics therefore have strong reasons to critically reflect on how national and transnational statistical agencies collect and analyze data (Link 1996). In this research note, we investigate how imprecisions arising from the principle to allocate R&D activities by firm’s main industry (NAICS/NACE/SIC) code affects aggregate statistics. On the one hand, highly servitized manufacturers may conduct R&D which is directed towards the development of services rather than physical products. On the other hand, R&D intermediaries, factoryless goods producers and other firms classified as belonging to the service sector are conducting R&D that in essence is related to the development of physical products and manufacturing activities.

Examining survey data on Swedish firms, we find evidence suggesting that the latter effect dominates the former. NACE-based statistics suggest that 28% of all R&D is conducted by service industry firms. Our classification based on self-reported data suggests that only about 20% of all R&D is conducted in firms primarily oriented towards service activities. Similarly, while NACE-based statistics show that the service sector is responsible for 18% of all R&D investments, the alternative measures suggest figures at 10–15%. Together, these findings imply that the share of Swedish R&D activity which is associated with service-oriented firms and motivated by the development of service products is even lower than what traditional measurements would suggest.

Our results provide indications that comparison of service sector R&D across the Atlantic may be subject to systematic bias. Official statistics suggest that the service sector’s share of R&D expenditures is almost as high in Sweden as in the US.Footnote 11 We have found, however, that adjusting the Swedish measure using similar principles as those applied by the NSFFootnote 12 reduces the share of service R&D considerably. We find it plausible that these differences reflect patterns that would apply also to other European countries that, similar to the Swedish statistical authority, attribute R&D expenditure across sectors on the basis of firms’ official NACE codes. Official statistics already suggest that the service sector’s share of R&D spending is considerably higher in the US than in Europe, taken as a whole. Our results suggest that the fundamental differences between these economies in terms of R&D expenditures may be greater than what such statistics may suggest. This calls for further analysis of differences in how European and US firms engage in service development activities and for further efforts to study differences in how manufacturing-oriented R&D is organized.

The findings reported in this note also have implications for researchers’ use of firm-level R&D data. In particular, studies using firms’ industry classification as selection criteria are potentially subject to imprecision. In order to hedge against any bias caused by such imprecision, researchers would be well-advised to pay attention to the cases where the three criteria compared in this note would seem to produce the most contrasting views of manufacturing versus service orientation of firms. In particular, researchers may want to…

-

… consider, where possible, to use survey data on the use of R&D by activity (NAICS) or product group (SPIN) as a basis for re-classifying the industry status of firms

-

… re-classify the industry status of R&D-performing firms within groups on the basis of existing classification of other (larger) firms within the group

-

… think carefully about how to handle firms classified as belonging to ICT industry and to the R&D services industry.

Notes

For a discussion of alternatives to traditional activity-based classification, see Giertz (2000).

We believe that there are service firms which exploit new ideas to develop substantial improvements of existing services, but which do not report any R&D activities. This problem is however not further reflected upon or investigated in this research note.

While classifications based on industrial codes remains the standard, questions similar to this one have been used by statistical agencies in countries in northern and central Europe to seek to allocate R&D performed by service sector firm on behalf of costumers classified as manufacturing sector firms to the manufacturing sector (Duchêne et al. 2010).

As we later can see in Table 4, almost half (46%) of the R&D in service sector firms is funded by external means (internal means = 19.6% * 61,700 = 12,093; external means = 53.2% * 19,500 = 10,374). This indicates that almost half of the R&D reported by service sector firms is paid for by their clients or by other firms within their groups.

Beyond of the direct scope of this research note, our results suggest that the use of traditional industry classification may produce rather inaccurate images of the service economy in general. As shown in Table 1, the average service industry firm has just above one quarter of its revenues coming from sales of physical goods. At the level of the aggregate Swedish economy, this translates into a substantial difference between the relative size of service industries and the relative importance of service production. While 66 percent of total private sector turnover emanates from service industry firms, the share of turnover generated through services in the total economy is estimated to be 37 percent.

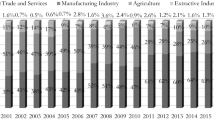

Further exploration of data available in the official reports published by Statistics Sweden confirms that the difference between the share of R&D performed by service sector firms, and the hare of R&D motivated by service development is not specific to the 2011 survey from which we draw our data. As shown in Fig. 1 in “Appendix” section, the gap is even larger in earlier (2005, 2007) and later (2015) editions of the survey rounds.

For simplicity, primary sector firms are considered together with manufacturing sector firms.

Revenues excluding financial and extraordinary income.

A full 81% of investments in extramural R&D are indeed made within a group structure, whereof 73% are cross-border (international) investments.

The National Science Foundation is responsible for producing the official R&D statistics for the US.

References

Adams, J. D. (2005). Industrial R&D laboratories: Windows on black boxes? Journal of Technology Transfer, 30(1/2), 129–137.

Audretsch, D. B., & Feldman, M. P. (1996). R&D spillovers and the geography of innovation and production. The American Economic Review, 86(3), 630–640.

Awuku-Budu, C., & Sveikauskas, L. (2015). Allocation of company research and development expenditures to industries using a Tobit model. US Census Bureau Center for Economic Studies. Paper No. CES-WP-15-42.

Bernard, A. B., & Fort, T. C. (2015). Factoryless goods producing firms. American Economic Review, 105(5), 518–523.

Bhojraj, S., Lee, C. M. C., & Oler, D. K. (2003). What’s my line? A comparison of industry classification schemes for capital market research. Journal of Accounting Research, 41, 745–774.

Broström, A., & Karlsson, S. (2017). Mapping research on R&D, innovation and productivity: A study of an academic endeavor. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 26(1–2), 6–20.

Christensen, J. L. (2013). The ability of current statistical classifications to separate services and manufacturing. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 26, 47–60.

Coombs, R., & Miles, I. (2000). Innovation, measurement and services: The new problematique. In J. S. Metcalfe & I. Miles (Eds.), Innovation systems in the service economy (pp. 85–103). New York: Springer.

Djellal, F., Francoz, D., Gallouj, C., Gallouj, F., & Jacquin, Y. (2003). Revising the definition of research and development in the light of the specificities of services. Science and Public Policy, 30(6), 415–429.

Duchêne, V., Lykogianni, E., & Verbeek, A. (2010). R&D in services industries and the EU-US R&D investment gap. Science and Public Policy, 37(6), 443–453.

Evangelista, R. (2000). Sectoral patterns of technological change in services. Economics of Innovation and New Technology, 9(3), 183–222.

Gallaher, M. P., Link, A. N., & Petrusa, J. E. (2006). Innovation in the US service sector. London: Routledge.

Gallaher, M. P., & Petrusa, J. E. (2006). Innovation in the US service sector. Journal of Technology Transfer, 31, 611–628.

Giertz, E. (2000). Measuring success: Identifying performance indicators. Malmö: Celemi.

Graham, J. M., Davis, S., Lippoldt, D., Mann, C. L., & Triplett, J. (2007). The measure of a nation: Quantifying innovative strength through improved service sector metrics. NBR special report 11. Seattle, Washington: National Bureau of Asian Research.

Hicks, D. (2011). Structural change and industrial classification. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 22, 93–105.

Hollenstein, H. (2003). Innovation modes in the Swiss service sector: A cluster analysis based on firm-level data. Research Policy, 32, 845–863.

Howells, J. (2008). New directions in R&D: Current and prospective challenges. R&D Management, 38, 241–252.

Jankowski, J. E. (2001). Measurement and growth of R&D within the service economy. Journal of Technology Transfer, 26, 323–336.

Kahle, K. M., & Walkling, R. A. (1996). The impact of industry classifications on financial research. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 31, 309–335.

Leiponen, A., & Drejer, I. (2007). What exactly are technological regimes? Intra-industry heterogeneity in the organization of innovation activities. Research Policy, 36(8), 1221–1238.

Link, A. N. (1996). On the classification of industrial R&D. Research Policy, 25, 397–401.

Love, J. H., Roper, S., & Hewitt-Dundas, N. (2010). Service innovation, embeddedness and business performance: Evidence from Northern Ireland. Regional Studies, 44(8), 983–1004.

Miles, I. (2007). Research and development (R&D) beyond manufacturing: The strange case of services R&D. R&D Management, 37(3), 249–268.

National Science Foundation, Division of Science Resources Statistics. (2005). National patterns of research and development resources: 2003. NSF 05-30. Arlington: Brandon Shackelford.

Pavitt, K., Robson, M., & Townsend, J. (1989). Technological accumulation, diversification and organisation in UK companies, 1945–1983. Management Science, 35(1), 81–99.

Romer, P. M. (1990). Endogenous technological change. Journal of Political Economy, 98, S71–S102.

Tassey, G. (2004). Underinvestment in public good technologies. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 30(1–2), 89–113.

Tether, B. S. (2005). Do services innovate (differently)? Insights from the European Innobarometer Survey. Industry and Innovation, 12(2), 153–184.

Tether, B. S., & Tajar, A. (2008a). Beyond industry–university links: Sourcing knowledge for innovation from consultants, private research organisations and the public science-base. Research Policy, 37(6), 1079–1095.

Tether, B. S., & Tajar, A. (2008b). The organisational-cooperation mode of innovation and its prominence amongst European service firms. Research Policy, 37, 720–739.

Trigo, A. (2013). The nature of innovation in R&D- and non-R&D-intensive service firms: Evidence from firm-level latent class analysis. Industry and Innovation, 20, 48–68.

Vang, J., & Zellner, C. (2005). Introduction: Innovation in Services. Industry and Innovation, 12(2), 147–152.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

See Fig. 1.

Source Authors’ summary of official data from statistics Sweden (www.scb.se)

Share of Swedish R&D expenditure attributed to service firms and to service development activities.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Broström, A., Giertz, E. Service development accounts for an even smaller share of European R&D investments than we may think. J Technol Transf 46, 1256–1267 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9592-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9592-x