Abstract

In spite of the extensive presence of Science Parks in developed countries, it is still unclear whether they have been successful in fostering the innovation performance of new technology-based firms (NTBFs). The aim of this paper is to help answer exactly this question. Using an unbalanced panel of 7691 observations associated with 1933 Spanish NTBFs (2007–2013), located both on-park and off-park, our empirical results show no evidence of a direct relationship between being located on a Science Park and the innovation performance of the NTBFs. However, our findings reveal that Science Parks play a positive selection role by attracting NTBFs with high technological capabilities (indirect effect). Moreover, our results also indicate that the decision to locate in a Science Park may enhance the innovation performance of NTBFs that collaborate and jointly export (moderating effect). This paper provides new explanations that help provide a better understanding of the effects of Science Parks on innovation performance and also outlines several practical implications.

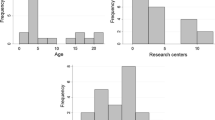

Source own elaboration

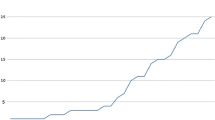

Source own elaboration

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Eveleens et al. (2016) presented a broad review of how network-based incubations influence start-up performance and they also obtained inconclusive results.

The classic models of asymmetric information pioneered by Akerlof (1970) in his “market for lemons” would assume that potential entrants have private information regarding their specific capabilities.

Following Eveleens et al. (2016), these specific capabilities would include absorptive capacity, network capacity and the relational capability of managing shared resources.

The data, questionnaire and a description of each variable are available online http://icono.fecyt.es/PITEC/Paginas/descarga_bbdd.aspx. This database provides some anonymized data in order to provide individual level information and to maintain the confidentiality required by data protection laws. López (2011) describes the procedure applied at the PITEC and demonstrates that the use of anonymized data from PITEC instead of original data produces reliable results.

The survey methodology follows the Guidelines proposed by the OECD for the collection and interpretation of data on innovation (Oslo Manual). The sampling design tries to minimize the sampling errors in the different phases and there are controls that guarantee a suitable quality level for the whole process. Finally, this survey is designed to deal more accurately with the innovation behavior of Spanish firms longitudinally.

Unfortunately, with the available information we cannot compare our results with those obtained in a period of economic growth.

We add one year to avoid ages of zero (Fukugawa 2006). Moreover, we use this variable in logarithmic form because one year might be insignificant to a middle aged firm but could be of great importance to a newly-established firm.

With the exception of the binary variables, which should have the possible values of 0 and 1, we mean centered the predictor variables in all the regression models to minimize multicollinearity (Aiken and West 1991).

The use of matched samples is another approach widely used in the literature (e.g. Westhead and Storey 1994; Löfsten and Lindelöf 2002; Fukugawa 2006). However, it has important limitations, especially for the objectives of our study. There is no reliable and cost-effective way to identify an adequate comparison group (Mian 1997); it provokes a sample bias; and as Ferguson and Olofsson (2004, p. 9) stated, It is difficult to know whether observed differences between the groups being compared are associated with the issue being studied, or a result of different samplings.

References

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Akerlof, G. (1970). The market for lemons: Quantitative uncertainty and the market mechanism. Quaterly Journal of Economics, 84(3), 488–500. doi:10.2307/1879431.

Albahari, A., Barge-Gil, A., Pérez-Cantó, S., & Modrego, A. (2017). The influence of Science and Technology Parks characteristics on firms’ innovation results. Papers in Regional Science. doi: 10.1111/pirs.12253.

Appold, S. J. (1991). The location processes of industrial research laboratories. The Annals of Regional Science, 25(2), 131–144. doi:10.1007/BF01581891.

Audretsch, D. B., Lehmann, E. E., & Wright, M. (2014). Technology transfer in a global economy. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 39(3), 301–312. doi:10.1007/s10961-012-9283-6.

Bakouros, Y. L., Mardas, D. C., & Varsakelis, N. C. (2002). Science Park, a high tech fantasy? An analysis of the Science Parks of Greece. Technovation, 22(2), 123–128. doi:10.1016/S0166-4972(00)00087-0.

Baptista, R., & Swann, P. (1998). Do firms in clusters innovate more? Research Policy, 27, 525–540.

Belderbos, R., Carree, M., & Lokshin, B. (2004). Cooperative R&D and firm performance. Research Policy, 33(10), 1477–1492. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2004.07.003.

Belderbos, R., Carree, M., Lokshin, B., & Sastre, J. F. (2015). Inter-temporal patterns of R&D collaboration and innovative performance. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(1), 123–137. doi:10.1007/s10961-014-9332-4.

Bell, G., & Zaheer, A. (2007). Geography, networks, and knowledge flow. Organization Science, 18(6), 955–972. doi:10.1287/orsc.1070.0308.

Bengtsson, L., & Löwegren, M. (2001). Internationalisation in Nordic and Baltic Science Parks (p. P99133). Project: Final Report to Nordisk Industrifond.

Bergek, A., & Norrman, C. (2008). Incubator best practice: A framework. Technovation, 28(1), 20–28. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2007.07.008.

Butchart, R. I. (1987). A new UK definition of the high technology industries. Economic Trends, 400, 82–88.

Carvalho, L. (2009). Four challenges for a new Science Park: AvePark in Guimaraes. Portugal. Urban Research and Practice, 2(1), 103–108. doi:10.1080/17535060902727090.

Cassiman, B., & Veugelers, R. (2002). R&D cooperation and spillovers: Some empirical evidence from Belgium. American Economic Review, 92(4), 1169–1184. doi:10.1257/00028280260344704.

Cassiman, B., & Veugelers, R. (2006). In search of complementarity in innovation strategy: Internal R&D and external knowledge acquisition. Management Science, 52(1), 68–82. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1050.0470.

Chan, K. F., & Lau, T. (2005). Assessing technology incubator programs in the Science Park: The good, the bad and the ugly. Technovation, 25(10), 1215–1228. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2004.03.010.

Chan, K. A., Oerlemans, L. A. G., & Pretorius, M. W. (2010). Knowledge exchange behaviors of Science Park firms: The innovation hub scene. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 22(2), 207–228. doi:10.1080/09537320903498546.

Chyi, Y. L., Lai, Y. M., & Liu, W. H. (2012). Knowledge spillovers and firm performance in the high-technology industrial cluster. Research Policy, 41(3), 556–564. doi:10.1093/cep/byi010.

Coeurderoy, R., Cowling, M., Licht, G., & Murray, G. (2012). Young firm internationalization and survival: Empirical tests on a panel of ‘adolescent’new technology-based firms in Germany and the UK. International Small Business Journal, 30(5), 472–492. doi:10.1177/0266242610388542.

Cohen, W. M., & Levinthal, D. A. (1990). Absorptive capacity: A new perspective on learning and innovation. Administrative Science Quarterly, 35(1), 128–152. doi:10.2307/2393553.

Colombo, M. G., & Delmastro, M. (2002). How effective are technology incubators? Evidence from Italy. Research Policy, 31(7), 1103–1122. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(01)00178-0.

Cooper, A. C. (1971). The founding of technologically-based firms. Milwaukee: The Center for Venture Management.

Dahl, M., & Pedersen, C. (2004). Knowledge flows through contact in industrial clusters: Myth or reality? Research Policy, 33(10), 1673–1683.

Díez-Vial, I., & Fernández-Olmos, M. (2015). Knowledge spillovers in science and technology parks: How can firms benefit most? The Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(1), 70–84. doi:10.1007/s10961-013-9329-4.

Eveleens, C. P., van Rijnsoever, F. J., & Niesten, E. M. (2016). How network-based incubation helps start-up performance: A systematic review against the background of management theories. The Journal of Technology Transfer. doi:10.1007/s10961-016-9510-7.

Fariñas, J. C., & López, A. (2007). Las empresas pequeñas de base tecnológica en España: delimitación, evolución y características. Economía industrial, 363, 149–160.

Felsenstein, D. (1994). University-related Science Parks –“Seedbeds” or “Enclaves” of Innovation? Technovation, 14(2), 93–110. doi:10.1016/0166-4972(94)90099-X.

Ferguson, R., & Olofsson, C. (2004). Science Parks and the development of NTBFs—location, survival and growth. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(1), 5–17. doi:10.1023/B:JOTT.0000011178.44095.cd.

Filatotchev, I., Liu, X., Lu, J., & Wright, M. (2011). Knowledge spillovers through human mobility across national borders: Evidence from Zhongguancun Science Park in China. Research Policy, 40(3), 453–462. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2011.01.003.

Fukugawa, N. (2006). Science Parks in Japan and their value-added contributions to new technology-based firms. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 24(2), 381–400. doi:10.1016/j.ijindorg.2005.07.005.

Fukugawa, N. (2013). University spillovers into small technology-based firms: Channel, mechanism, and geography. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 38(4), 415–431. doi:10.1007/s10961-012-9247-x.

Fukugawa, N. (2016). Knowledge spillover from university research before the national innovation system reform in Japan: Localisation, mechanisms, and intermediaries. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, 24(1), 100–122. doi:10.1080/19761597.2016.1141058.

Gibson, L., Lim, J., & Paavlakovich-Kochi, V. (2013). The university research park as a micro-cluster: Mapping its development and anatomy. Studies in Regional Science, 43(2), 177–189. doi:10.2457/srs.43.177.

Goffin, K., & Koners, U. (2011). Tacit knowledge, lessons learnt, and new product development. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 28(2), 300–318. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5885.2010.00798.x.

González-Pernía, J. L., Parrilli, M. D., & Peña-Legazkue, I. (2015). STI–DUI learning modes, firm–university collaboration and innovation. Journal of Technology Transfer, 40(3), 475–492. doi:10.1007/s10961-014-9352-0.

Granstrand, O. (1998). Towards a theory of the technology-based firm. Research Policy, 27(5), 465–489. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(98)00067-5.

Griliches, Z. (1992). The search for R&D spillovers. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 94(Supplement), 29–47.

Grunert, K. G., & Traill, B. (2012). Products and process innovation in the food industry. Berlin: Springer.

Guadix, J., Carrillo-Castrillo, J., Onieva, L., & Navascués, J. (2016). Success variables in science and technology parks. Journal of Business Research, 69(1), 4870–4875.

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Hannan, M. T., & Freeman, J. (1984). Structural inertia and organizational change. American Sociological Review, 49(2), 149–164. doi:10.2307/2095567.

Hobbs, K.G., Link, A.N. & Scott, J.T. (2016). Science and technology parks: An annotated and analytical literature review. The Journal of Technology Transfer, in press (on line first). doi:10.1007/s10961-016-9522-3.

Huang, K., Yu, C. J., & Seetoo, D. J. (2012). Firm innovation in policy-driven parks and spontaneous clusters: The smaller firm the better. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 37, 715–731. doi:10.1007/s10961-012-9248-9.

Inkpen, A. C., & Pien, W. (2006). An examination of collaboration and knowledge transfer: China–Singapore Suzhou Industrial Park. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 779–811. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00611.x.

Lamperti, F., Mavilia, R., & Castellini, S. (2015). The role of Science Parks: A puzzle of growth, innovation and R&D investments. The Journal of Technology Transfer. doi:10.1007/s10961-015-9455-2.

Liberati, D., Marinucci, M., & Tanzi, G. M. (2016). Science and Technology Parks in Italy: Main features and analysis of their effects on the firms hosted. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 41, 694–729. doi:10.1007/s10961-015-9397-8.

Lindelöf, P., & Löfsten, H. (2003). Science Park location and new technology-based firms in Sweden–implications for strategy and performance. Small Business Economics, 20(3), 245–258. doi:10.1023/A:1022861823493.

Lindelöf, P., & Löfsten, H. (2004). Proximity as a resource base for competitive advantage: University–industry links for technology transfer. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 29(3–4), 311–326. doi:10.1023/B:JOTT.0000034125.29979.ae.

Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2006). U.S. university research parks. Journal of Productivity Analysis, 25(1–2), 43–55. doi:10.1007/s11123-006-7126-x.

Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2007). The economics of university research parks. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 23(4), 661–674. doi:10.1093/icb/grm030.

Link, A. N., & Scott, J. T. (2015). Research, science, and technology parks: Vehicles for technology transfer. In A. N. Link, D. S. Siegel, & M. Wright (Eds.), The Chicago handbook of university technology transfer and academic entrepreneurship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Little, A. (1977). New technology-based firms in the United Kingdom and the Federal Republic of Germany. London: Wilton House.

Löfsten, H., & Lindelöf, P. (2001). Science Parks in Sweden–industrial renewal and development? R&D Management, 31(3), 309–322. doi:10.1111/1467-9310.00219.

Löfsten, H., & Lindelöf, P. (2002). Science Parks and the growth of new technology-based firms—academic-industry links, innovation and markets. Research Policy, 31(6), 859–876. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(01)00153-6.

Löfsten, H., & Lindelöf, P. (2003). Determinants for an entrepreneurial milieu: Science Parks and business policy in growing firms. Technovation, 23(1), 51–64. doi:10.1016/S0166-4972(01)00086-4.

Löfsten, H., & Lindelöf, P. (2005). R&D networks and product innovation patterns—academic and non-academic new technology-based firms on Science Parks. Technovation, 25(9), 1025–1037. doi:10.1016/j.technovation.2004.02.007.

López, A. (2011). Effect of microaggregation on regression results: An application to Spanish innovation data. The Empirical Economics Letters, 10(12), 1265–1272.

Malairaja, C., & Zawdie, G. (2008). Science Parks and university-industry collaboration in Malaysia”. Technology Analysis and Strategic Management, 20(6), 727–739. doi:10.1080/09537320802426432.

Mian, S. A. (1997). Assesing and managing the university technology business incubator: An integrative framework. Journal of Business Venturing, 12(4), 251–285. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.04.032.

Monck, C. P., Quintas, P. R., Porter. R. B., Storey, D. J., & Wynarczyk. P. (1988). Science Parks and the Growrh o/High Technolog.v Firins. London & New York: Croom Hehi.

Montoro-Sánchez, A., Ortiz-de-Urbina-Criado, M., & Mora-Valentín, E. M. (2011). Effects of knowledge spillovers on innovation and collaboration in science and technology parks. Journal of Knowledge Management, 15(6), 948–970. doi:10.1108/13673271111179307.

Nieto, M. J., & Santamaria, L. (2010). Technological collaboration: Bridging the innovation gap between small and large firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(1), 46–71. doi:10.1111/j.1540-627X.2009.00286.x.

Phan, P. H., Siegel, D. S., & Wright, M. (2005). Science Parks and incubators: Observations, synthesis and future research. Journal of Business Venturing, 20(2), 165–182. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2003.12.001.

Quintas, P., Wield, D., & Massey, D. (1992). Academic-industry links and innovation—questioning the Science Park model. Technovation, 12(3), 161–175. doi:10.1016/0166-4972(92)90033-E.

Salomon, R. M., & Shaver, J. M. (2005). Learning by exporting: New insights from examining firm innovation. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 14(2), 431–460. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9134.2005.00047.x.

Salvador, E. (2011). Are Science Parks and incubators good “brand names” for spin-offs? The case study of Turin. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 36, 203–232. doi:10.1007/s10961-010-9152-0.

Siegel, D. S., Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (2003a). Assessing the impact of university Science Parks on research productivity: Exploratory firm-level evidence from the United Kingdom. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 21(9), 1357–1369. doi:10.1016/S0167-7187(03)00086-9.

Siegel, D. S., Westhead, P., & Wright, M. (2003b). Science Parks and the performance of new technology-based firms: A review of recent U. K. evidence and an agenda for future research. Small Business Economics, 20(2), 177–184. doi:10.1023/A:1022268100133.

Sofouli, E., & Vonortas, N. S. (2007). S&T parks and business incubators in middle-sized countries: The case of Greece. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 32(5), 525–544. doi:10.1007/s10961-005-6031-1.

Squicciarini, M. (2008). Science Parks’ tenants versus out-of-Park firms: Who innovates more? A duration model. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 33(1), 45–71. doi:10.1007/s10961-007-9037-z.

Stinchcombe, A. L. (1965). Organizations and social structure. Handbook of organizations, 44(2), 142–193.

Storey, D., & Tether, B. (1998). New technology-based firms in the European Union: An introduction. Research Policy, 26(9), 933–946. doi:10.1016/S0048-7333(97)00052-8.

Teece, D. J. (1986). Profiting from technological innovation: Implications for integration, collaboration, licensing and public policy. Research Policy, 15(6), 285–305. doi:10.1016/0048-7333(86)90027-2.

UNCTAD (2015). Policies to promote collaboration in science, technology and innovation for development: The role of science, technology and innovation parks. TD/B/C.II/30, pp 1–17.

Vásquez-Urriago, Á. R., Barge-Gil, A., & Rico, A. M. (2016). Science and Technology Parks and cooperation for innovation: Empirical evidence from Spain. Research Policy, 45(1), 137–147. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2015.07.006.

Vedovello, C. (1997). Science Parks and university-industry interaction: Geographical proximity between the agents as a driving force. Technovation, 17(9), 491–531. doi:10.1016/S0166-4972(97)00027-8.

Wennberg, K., & Lindqvist, G. (2010). The effect of clusters on the survival and performance of new firms. Small Business Economics, 34(3), 221–241. doi:10.1007/s11187-008-9123-0.

Westhead, P. (1997). R&D ‘inputs’ and ‘outputs’ of technology-based firms located on and off Science Parks. R&D Management, 27(1), 45–62. doi:10.1111/1467-9310.00041.

Westhead, P., & Cowling, M. (1995). Employment change in independent owner-managed high-technology firms in Great Britain. Small Business Economics, 7(2), 111–140. doi:10.1007/BF01108686.

Westhead, P., & Storey, D. J. (1994). An assessment of firms located on- and off-Science Parks in the UK. London: HMSO.

Wiersema, M. F., & Bowen, H. P. (2009). The use of limited dependent variable techniques in strategy research: issues and methods. Strategic Management Journal, 30(6), 679–692. doi:10.1002/smj.758.

Yang, C.-H., Motohashi, K., & Chen, J.-R. (2009). Are new technology-based firms located on Science Parks really more innovative? Research Policy, 38(1), 77–85. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2008.09.001.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by project grant ECO2016-77-P (AEI/FEDER, UE) and the COMPETE research group (S125; Government of Aragón -Spain- and FEDER).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ramírez-Alesón, M., Fernández-Olmos, M. Unravelling the effects of Science Parks on the innovation performance of NTBFs. J Technol Transf 43, 482–505 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9559-y

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-017-9559-y