Abstract

This article focuses on perceptions of the Jewish ultra-Orthodox population in Israel—a religious minority—regarding guidelines enacted by the Israeli Ministry of Health (MOH) during the country’s second wave of COVID-19, and ways the community coped with the pandemic. Semi-structured interviews with 30 ultra-Orthodox individuals revealed five major discourses reflecting participants’ perceptions. Three discourses objected to MOH guidelines, while the other two aligned with them. The study’s findings also indicate a lack of cooperation between the ultra-Orthodox population and state health authorities, emphasizing the need to implement culturally adapted health interventions. Study limitations are discussed, and future research recommendations are provided.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) population is a minority group in Israeli society and the Jewish world. In Israel, the Haredi community is composed of 1,226,000 people, constituting 12.5% of the country’s population. The community is characterized by a particularly high fertility rate (6.9 children per woman), a young population (60% under the age of 20), and low socioeconomic status (Malach & Cahaner, 2021).

The Haredi population is classified into three major streams: (1) Hasidim, whose society is organized around a Hasidic “court” that is led by a rebbe, who shapes the nature of his congregation; (2) Lithuanian, characterized by a relative openness to modern life as compared to the Hasidim; and (3) Sephardim, a stream comprised of Jews from North Africa and the Middle East who have adopted the Lithuanian lifestyle (Brown, 2017).

While the Haredi population is divided into many subgroups, they all share numerous attributes: adherence to the strictest interpretation of Jewish law; commitment of males to Torah study, with emphasis on the importance of communal gathering for study and prayer; obedience to religious authority (rabbis); strict modesty norms regarding women’s clothing; objection to or reservations about a pre-messianic State of Israel; isolation from majority society by concentrating in enclaves, in certain cities and neighborhoods, due to the perception that the external world is threatening the community’s existence.

These attributes create an inherent tension between the Haredi community and the surrounding majority population (Friedman, 1991). Despite this, the boundaries between the Haredi community and majority society do allow some flexibly and may adjust under certain circumstances such as some police operations, even as religious constraints may pose obstacles for advancing community cooperation with such state organizations (Yogev, 2021).

The literature distinguishes between the mainstream moderate camp of Haredi society in Israel—the majority—and the minority extremist camp, affiliated with the Eda haHaredit. The Eda haHaredit is the framework that unites the groups and circles that refuse to recognize the legitimacy of the State of Israel as a Jewish State. This camp adopted a hard-line anti-Zionist stance and demanded that its members isolate themselves totally from the Zionist enterprise and the State of Israel (Friedman, 1991; Keren-Kratz, 2016). Typically, the mainstream camp follows the state’s laws and avoids clashes with state authorities, while the extremist camp tends to break state laws, often in contentious and violent ways.

The Israeli outbreak of COVID-19, beginning in March 2020, effected the Haredi communities in ways similar to other worldwide religious communities and congregations (Shapiro et al., 2020). The COVID-19 crisis led governments worldwide to implement guidelines that altered the nature of person-to-person interactions, which had profound implications for gatherings within religious settings and organizations (Osei-Tutu et al., 2021). Since religious gatherings can attract large numbers of participants and contribute to the spread of viruses, religious congregations and institutions were closed in many countries (DeFranza et al., 2020). The Israeli Ministry of Health (MOH) demanded the same from religious congregations and institutions in Israel, including those in the Haredi community: where it ordered the closure of educational institutions, including yeshivas (Jewish educational institutions for religious studies), and greatly restricted the number of worshipers in synagogues (Schroeder et al., 2021; Shapiro et al., 2020).

On March 25 2020, the government declared a lockdown which added more restrictions and legal sanctions to the previous guidelines (Waitzberg et al., 2020). These steps aroused opposition within many circles of Israel’s Haredi community, leading them to violate the guidelines intentionally. As a result, the rate of infection among the Haredi population was three times higher than the non-Haredi rate: 37% of all Israeli patients in 2020 were Haredim—from a population which is only 12.5% of the total (Malach & Cahaner, 2021). Similarly, until mid-October 2020, the death rates among the Haredi community were four times higher than their share of the general population (Weinreb, 2021).

Despite this, when a second lockdown was declared in Israel in September 2020 during the second wave of COVID-19 (July 2020–February 2021), violations of health guidelines by the Haredim intensified and were followed by contentious protests and violence against law enforcement officers. This reality led the authors to examine perceptions of the Haredim of the MOH guidelines and how the community coped with the pandemic during its second wave—a period of time during which vaccines did not yet exist, and it was not clear if and when they would.

As every religious minority group has unique beliefs, practices, and norms that can affect its members’ health and health behaviors, it is important to understand how the dynamic during COVID-19 varied among different religious minorities (Shapiro et al., 2020). While many studies have been published about the conduct of various religious minorities during COVID-19 (e.g., DeFranza et al., 2020; Michaels et al., 2022; Osei-Tutu et al., 2021; Weinberger-Litman et al., 2020), the conduct of the Haredi community in Israel—a religious minority subculture—has hardly been investigated (see Schroeder et al., 2021), particularly from the community’s own perspective.

The present study aims to fill this lacuna. Understanding the Haredi community perspectives and its internal discourse regarding the MOH’s guidelines and ways of coping with the pandemic sheds light on the unique aspects of the Haredi community that relate to health promotion and the spread of disease. On a more global level, the study provides insights regarding the behaviors of religious minority groups in the context of health and disease, in general, and during pandemics, in particular. The study also suggests ways to improve policies and plans for coping with epidemics among the Haredi population as well as other religious and ethnic minorities, and reducing health inequalities.

Health Behaviors in the Haredi Community

Violation of MOH’s guidelines by Israeli Haredim did not start with COVID-19. A previous notable incident was the Israeli measles outbreak of 2007. Despite high national measles immunization (94–95%), in August of that year there was a large measles outbreak among extreme Haredi groups in Jerusalem, cause by long-standing noncompliance of those groups (Stein-Zamir et al., 2008). This approach might demonstrate both a basic distrust in the "Zionist" health system of some extreme Haredi groups and an inner Haredi discourse involving both fake and misleading data.

Nevertheless, maintaining one’s health in the Haredi society is perceived as a religious obligation, relying on the religious command: “And you should take great care for your souls” (Deuteronomy, 4:15). Yet, the Haredi population in Israel engages in low levels of health-promoting behaviors (Leiter et al., 2019), similar to other populations that are characterized by a low socioeconomic status (Kail et al., 2019), mainly due to economic reasons and lack of awareness (Bayram & Donchin, 2019).

Still, the general health level of the Haredi population is considered high relative to the general population (Chernichovsky & Sharony, 2015). In general, it has longer life expectancy than other Israelis (Pinchas-Mizrachi et al., 2020) thanks to aspects embedded in the religion known to promote health, such as religious rituals and practices, a faith-based worldview, and particularly high social capital (Chernichovsky & Sharony, 2015). Many studies refer specifically to elements of social capital embedded in the religious community that promote health behaviors and improve health among believers while emphasizing the role of clergy, religious institutions, religious affiliations, inter-communal welfare, and networking, and their importance in providing privileged access to resources (Milstein et al., 2020; Satariano, 2020; Shapiro & Sharony, 2018). Yet, social capital can sometimes have negative consequences. It can restrict individual freedoms and bar outsiders from gaining access to the same resources through particularistic preferences (Portes, 1998). Social capital can also have negative impact when religious group norms conflict with medically appropriate actions (Shapiro, 2021).

One of the major components of the Haredi population social capital is the strong connection with religious leaders—that is, the rabbis—and “health mediators.” Rabbis are the ultimate religious authorities for counseling in all areas of life, including health issues (Zalcberg, 2015). They outline the paths and perceptions of a Haredi individual (Brown, 2017). As such, they have a major effect on his or her health behaviors (Coleman-Brueckheimer & Dein, 2011).

“Health mediators,” known as askanim (as they will be referred to throughout the text), are figures in the community who are considered authorities on health-related issues. They mediate between community members and health professionals and service providers outside of the Haredi world (Coleman Brueckheimer et al., 2009).

While the askanim usually deal with individuals, the rabbis have to consider the many facets of the community well-being, which cannot be measured only by the physical health of its individuals, but also by their spiritual well-being, which from the Haredi perspective, is threatened by the pandemic regulations (Zalcberg & Block, 2021). From this point of view, in the case of COVID-19, there was a conflict of values for the rabbis. On the one hand there is the individual who is commanded to keep safe and healthy, on the other hand a whole community might suffer spiritually, if everybody will act for themselves. This is also the place where the role of the rabbi gets into the picture, seeking to balance between the physical health of individuals and the spiritual well-being of his community.

Both rabbis and askanim also influence the Haredi population access to health knowledge—a variable that is considered a significant factor in health promotion (Khan et al., 2021; Peles et al., 2018). With the outbreak of COVID-19, by employing misleading data, many rabbis and askanim encouraged violation of MOH instructions, calling on followers to attend yeshivas and synagogues when such gatherings were forbidden (Zalcberg & Block, 2021).

In light of the conduct of the Haredi population during the second wave of COVID-19 and the high COVID-19 morbidity rates among the Haredi population, this study focuses on the following question: What were the perceptions of the Haredim regarding the MOH guidelines and how did the community cope with the pandemic during the second wave of COVID-19 in Israel?

Method

The Research Paradigm

The current study utilized a qualitative paradigm (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011) that focuses on reality—as it is perceived by those living it—while emphasizing a context-informed approach (Roer-Strier & Sands, 2015). This approach allows for insights into participants’ experiences through their unique social-cultural context and the significance that they attach to those experiences.

Sample and Sampling Method

The study population included men and women 18 years of age or older from the various groups of Haredi society in Israel. To recruit participants from this population, the authors reached out to their contacts in the Haredi community, who were known to them from previous studies they conducted on Haredi society. These contacts helped recruit participants for the current study. At a later stage, some of the participants referred the authors to additional participants (“snowball sampling”). At the end of this process, the final sample included 30 participants (18 men and 12 women) who were willing to share their knowledge and perceptions regarding the research topic.

The age of participants ranged from twenty-five to sixty-five; all were married, with seven children on average. Twenty-one participants were from the moderate mainstream camp of ultra-Orthodoxy, and nine were affiliated with the extremist circles (self-identified with a group affiliated to the Eda haHaredit). All lived in urban areas. Ten participants worked in education, nine worked in business, financial services, and clerical work, seven (all male) dedicated their time to Torah study in yeshiva (Kollel), and two (women) were housekeepers (Table 1).

Data Collection

Data collection consisted of semi-structured interviews conducted in Hebrew, by the authors. The interviews were based on an interview guide that was formed on the basis of previous studies, which focused on aspects related to well-being and health of the Haredi population, as well as Haredi individuals’ attitudes toward the state authorities (Block, 2016; Zalcberg, 2017; Zalcberg & Block, 2021). The interview included topics related to perceptions regarding the MOH’s prohibition on gatherings for religious worship and family events, the MOH’s demand to close religious educational institutions, the obligation to go into quarantine and be tested for COVID-19 when an infection is suspected, and the appropriate steps for fighting the pandemic.

Since the interviews were conducted during the second wave of COVID-19 in Israel, to maintain social distance, nineteen interviews were conducted by phone and eleven by Zoom, according to the participant’s preference. Each interview lasted between 1 and 1.5 hours. The data collection took place from September 2020 to November 2020. With the participants’ consent, all interviews were documented—twenty-four were recorded and transcribed, and six were documented in writing, according to the participants’ preference.

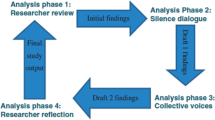

Data Analysis

Data analysis was based on the grounded theory approach (Strauss & Corbin, 1997), which is relevant for studies in which there is a general research question without a hypothesis to prove or disprove, as in the current study. The analysis, according to this approach, consists of two levels: The first is a general thematic analysis to identify major themes in the interviews and correspondence, and the second consists of uncovering the meanings underlying the surface-level data, as well as the meanings of the first-level categories.

The thematic analysis includes the following steps: First, authors familiarized themselves with the data by reading interviews several times. Second, authors together identified preliminary ideas by reading the first five interviews repeatedly, identifying segments representing discrete units of meaning. Then, codes were identified manually by the authors together,Footnote 1 and grouped into initial themes. As the authors continued reading, themes were revised. Finally, themes were refined, named, and interrelationships between them suggested.

Data saturation was reached when there was enough information to replicate the study when the ability to obtain additional new information has been attained, and when further coding is no longer feasible (Fusch & Ness, 2015).

Quality Assurance and Ethical Aspects

The study’s quality assurance was based on Lincoln and Guba’s criteria of qualitative research (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). The credibility of the findings was established by including participants from various Haredi groups in order to obtain a broad range of opinions on the subject; usage of an in-depth interview to encourage free and open dialogue; repetitive review of data collection and analysis processes; and engagement in a peer review process of the findings, and the implementation of recommendations.

Further, to reduce authors’ bias, there was an explicit focus on having the authors be aware of their own perceptions about the topic of study and an explicit effort to avoid guiding participants to discuss particular topics during the interview. This step supported the conformability of the findings. The transferability of findings was demonstrated by the inclusion of a detailed description of the study’s participants, the research process, and an explanation of how the findings fit within the relevant cultural context.

The study was conducted in accordance with the code of ethics as determined by the American Psychological Association (Campbell et al., 2010). As such, the study’s purpose was explained to participants prior to the start of the study. Participation was voluntary, and participants were notified that they would be able to withdraw from the study at any given time. Participants’ confidentiality and anonymity were ensured throughout all stages of the study, and included the use of pseudonyms and the omission of all identifying details from the current paper.

Findings

The analysis of the data identified five main discourses reflecting participants’ perceptions of the MOH guidelines and ways of coping with the pandemic during its second wave. Three of the discourses expressed objection toward MOH guidelines: (a) an educational-value discourse, which expressed strong opposition to the demand to close yeshivas, fearing young men would cease studying Torah; (b) a medical discourse, which objected to the requirements for COVID-19 tests and isolation when there is a suspicion of infection, and to the hospitalization of COVID-19 patients; and (c) a theological discourse, which explained the outbreak of the pandemic in theological terms related to women’s modesty, and accordingly argued that only improving female modesty would stop the pandemic.

The other two discourses were aligned with the MOH guidelines: (a) a discourse of compliance, which called for complying with the MOH guidelines in accordance with the instruction of a few religious leaders, and (b) a critical discourse, which called for complying with the MOH guidelines while sharply criticizing the rabbinical leadership that opposed them (Fig. 1).

Value-Educational Discourse

Most participants (25) strongly opposed the MOH guidelines, especially those related to temporarily closing yeshivas. The reason for this, in addition to fearing Torah study would be abandoned, that was mentioned strongly at the first wave of the pandemic (Zalcberg & Zalcberg Block, 2021), was participants fear that closing yeshivas would lead Haredi youth to loiter, drop out of yeshivas, and abandon the world of Torah. As one participant explained:

We strongly oppose shutting down the yeshivas. Beyond causing an abandonment of Torah, this will cause our boys to hang around in the street, and you know... it’s a slippery slope. Therefore, in some circles, there was a quiet call under the radar from the rabbis that yeshiva students would not be tested, even those who have symptoms. Because if there is a positive result, the MOH will immediately demand the institution be shut down, and then there is a great danger of loitering in bad places.

Along these lines, another participant stated:

If the yeshivas were shut down, many young people would be without any framework and would be exposed to a great risk of encountering secular young people. This is our real danger, that youth will abandon the world of Torah and the Haredi world. Therefore, the rabbis said to open the yeshivot at all costs.

The Haredi community was concerned with the high dropout rates of its youth before the COVID-19 outbreak, and the threat of yeshivas being shut down and Haredi youth loitering in the streets increased this fear, which the Haredim consider a significant “spiritual risk” (Nadan et al., 2019). For the Haredi community, this is a threat at the personal, family, and community level—a danger to the continuity of the world of Torah and religious life. For this reason, rabbis encouraged their followers to continue attending the yeshivas and did not try to stop their violent protests against the MOH guidelines.

The Medical Discourse

Several participants (8), especially those from the extremist circles, explained that their perceptions of the MOH guidelines resulted from their medical approach. In contrast to the MOH, they believe that there is no need for COVID-19 tests, even for those who are symptomatic or came in contact with a verified patient, because COVID-19 is a mild disease that passes within a few days. One participant who takes this position said:

I had a high fever and a strong cough, but I did not go to be tested. For what? You rest a bit, and it all passes. That’s what everyone did here. The MOH and the doctors just scare everyone. Do not believe them. You should not be afraid and let the disease take you over.

These participants also strongly opposed the hospitalization of verified patients with severe symptoms. In their view, hospitalization is not only ineffective but also increases the risk to the patient, exposing them to inappropriate treatment, neglect, and severe loneliness. As one participant explained, “At the hospital, doctors kill patients, and they die there alone. They should stay at home, with a family that takes care of them.”

To prevent the need for hospitalization, several askanim set up a system to provide free medical equipment and home care to seriously ill patients. One participant, an askan from the extremist camp, who took part in building this charitable organization, explained:

We have 89 oxygen concentrators and lots of vitamins and water with garlic, which the patient takes for a few days. We have someone who understands this and tells the patient what to take. After few days of this home care everything goes away. Among us, no one went to the hospital. Whoever went to the hospital - did not return.

These statements express some Haredi circles’ strong suspicion and mistrust of the medical establishment. Manifestations of this distrust also arose among many participants (9) from the moderate camp. According to some participants, their communities developed an attitude that advocates intentional mass infection, known as “herd infection.” As one participant noted, “We believe that everyone should be infected in order to be vaccinated. Therefore, not only do we not send for quarantine, but we even put all the young people together so that one can infect the other.”

This approach, openly challenging the MOH guidelines, was particularly noticeable among one of Israel’s most prominent Hasidic communities due, in part, to the popularity of its leader, the great rabbi of the Belz community, the Belzer Rebbe, Rabbi Yissachar Dov Rokeach. One participant belonging to this community said:

Our Rebbe conveyed that life should continue as usual. He instructed us to “read fewer newspapers,” that is, to reduce the exposure to “outside” information regarding COVID-19 guidelines, and gave the instruction: “be happy.” For his Hasidim [followers], the message to violate the MOH guidelines was clear.

The same participant added that their leader believed that the entire population would be infected sooner or later. Therefore, there was no point in disrupting the routine of daily life with efforts to prevent infections. Another participant from the same Hasidic community added:

The Rebbe thought that everyone should be infected, as everybody is always together in the yeshiva, so they will infect each other and go through it. The Rebbe expressed his attitude towards the MOH guidelines through the mass wedding he held for his grandson, which was attended by thousands of Hasidim, in high density and without masks. We have no disregard for human life but a different medical understanding of the situation.

The Theological Discourse

Through religion, individuals can make sense of many sorts of misfortunes, with one explanation being failure to follow a proper religious way of life (Osheim, 2008). This can be seen here, in the theological discourse, that sought to explain and give meaning to the COVID pandemic. Participants, mainly from the extremist circles (about eight people), created a linkage between a lack of modesty among the women within the community and the outbreak of the pandemic. According to them, the only solution to end the pandemic is strictly adhering to modesty codes relating to women and not strictly adhering to the MOH guidelines. As one of them explained:

We ask what God wants to tell us with this. Apparently, the women here are not modest enough. They walk in tight clothes and skirts [that are] too short. God wants to say that we need to be more modest. There is a real “measure against measure” here. So many women dress immodestly and expose their bodies in public, and now, because of COVID, everyone has to be covered with a mask and not be seen in public.

These participants further emphasized a link between women not covering their hair entirely and high morbidity rates. As one explained:

In recent years, many Haredi women walk with hats, leaving all their hair out, or, God forbid, with wigs, which are worse than real hair. Now comes COVID-19. Known [in Israel] as Corona, from the word crown, it implies in its name the violations of modesty rules concerning the crown of the Jewish woman—that is, the covering of her head.

A Discourse of Obedience

Not all participants saw the violation of modesty as the primary cause of the epidemic, nor considered yeshivas remaining open as a supreme value—when it involved a health risk. A minority of the participants (5) cited that they adhered to the MOH guidelines, following the instruction of their religious authority. As one of them noted:

We definitely obey the MOH’s instructions. The Rebbe said that we must. When the MOH just began with the demand for quarantine, one of the congregants was a verified patient. When our Rebbe found out, he immediately ordered all the people who came in contact with that man to go into quarantine, and about 200 hundred Hasidim obeyed and went into quarantine.

Another participant explained in a similar vein:

Our rabbi has a sickly girl, who is in a risk group. He immediately understood the danger of the epidemic, and immediately instructed us to act in accordance with all the MOH’s guidelines. I, as well as the rest of the community, of course obeyed our rabbi and acted accordingly.

Obedience to the religious leaders, the rabbis, even in matters beyond Jewish law, matters of everyday life, are considered a supreme value in Haredi society, and these participants followed MOH instructions mainly, if not only, to obey the rabbi who instructed them to do so.

The Critical Discourse

Among the participants who followed the MOH guidelines, a small minority (5) expressed criticisms of those leaders who did not encourage their followers to obey the MOH and went so far as to encourage them to violate the guidelines. Although only a few expressed this view, it could not be ignored. One participant noted:

The Haredi leadership had difficulty understanding the epidemiological-professional material, and it took them time to come up with a position that was consistent with the MOH. Haredi leaders always first oppose any change, and then they slowly internalize the need for it and take slow steps.

At the beginning of his remarks, this participant expressed guarded criticism of Haredi leaders, noting a shortcoming in their leadership, which he attributed to their lack of professional-medical knowledge. However, his careful remarks were possibly due to his own difficulty criticizing his leaders, as even if religious leaders lacked medical knowledge, most of them had access to relevant knowledge through the askanim and professionals with whom they are in constant contact (Coleman-Brueckheimet al., 2009). Indeed, this participant’s subsequent statements somewhat confirmed this assumption as he explained that the conduct of the religious leadership was deliberate, resulting from a fundamental conservatism that characterizes the Haredi worldview (Brown, 2017).

Others were harsher in their criticism. Some participants said they disobeyed their rabbis when they ordered followers to continue attending yeshivas as usual. One participant stated:

These are irresponsible rabbis who preached that the guidelines should be violated in the name of Torah study, which would protect against any disease, and used the Torah to gain legitimacy for violating the guidelines. I’m not willing to put anyone at risk. [...] The rabbi cannot repeal the Jewish law of maFintaining health. The Torah instructs us not to obey the leader when he contradicts the Torah!

This participant claimed a contradiction existed between the religious authority’s order and the Torah’s commandment, and he preferred to obey what he perceived to be the Torah’s commandment.

Several participants criticized the Belzer Rebbe, who held the mass wedding to his grandson. This Rebbe is one of the most prominent Haredi leaders in Israel, who typically cooperates with state authorities and institutions, especially on health matters. His conduct concerning the MOH guidelines during COVID-19 deviated from his usual conduct over the years. As one participant stated, “his behavior seems strange and incomprehensible. The Haredi population obey the rabbis, but we are not blind. We see there is a pandemic, there are sick people, and there are deaths.”

The Belzer Rebbe was sharply criticized even by some of his own Hasidim, which is not a trivial matter. One of the participants that affiliate with Belz said:

This is about killing! The Rebbe not only instructs [us] to harm the law but Jewish morality. Many Haredim are angry with him because of this conduct. Although the Rebbe invited all the Hasidim to his grandson’s wedding, I did not go. I am not willing to be part of it. I stood my ground without blinking. Any leader can be wrong, even great leaders, and he made a big mistake.

Though critical, this participant maintained that the Belzer Rebbe was a great leader and, to a certain extent, tried to protect him, claiming the Rebbe did not act out of malice and just happened to be wrong in this case.

In this context it’s worth noting that in normal times the Haredi society usually follows all the medical system’s guidelines. The COVID was a unique case when even parts of the non-Haredi public also didn’t follow the regulation.

Discussion

The study’s findings revealed two primary perceptions of the MOH guidelines and ways of dealing with COVID-19 among the Haredi population in Israel during its second wave. The first, expressed by most participants, opposed the guidelines and embraced violating them. The second, expressed by a minority of participants, supported the guidelines and believed they should be followed.

The negative perception of the guidelines was expressed in three discourses: the value-educational, the medical, and the theological. The value-educational discourse emphasized the spiritual risk of young people leaving the world of Torah and the Haredi world if the yeshivas were closed. This risk, according to participants, outweighs the risk of becoming infected. More broadly, like for any other religious minority, it reflects the constant threat Hardei society perceives itself to face—that the boundaries separating it from the outside world will be broken (Almond et al., 2011)—and the attempt to fight this threat at all costs, including the health of its members.

In this context, it is interesting to note that participants almost did not raise concerns about government guidelines affecting synagogue and life-cycle event attendance. This can be explained by the fact that this issue, of extreme concern to the Haredi population during the first wave—as seen in previous study (Zalcberg & Block, 2021)—during the second wave carried forward and was taken for granted by participants. During the second wave, the Haredi population became concerned by other aspect that was hardly (if at all) raised at the first wave, and the participants focused on it: The fear that closing yeshivas would lead Haredi youth to loiter, drop out of yeshivas, and abandon the world of Torah.

The medical discourse expressed a medical approach opposed to the MOH regarding the COVID-19 tests and hospitalizations and encourages herd infection, even if not formally. This discourse reveals that some Haredi circles preferred to preserve their “normal” life routine at the cost of widespread morbidity. This preference possibly stemmed from information disseminated in the media in the pandemic’s first and second waves that COVID-19 hardly affects young people. Since the Haredi population is primarily young (Malach & Cahner, 2021), these circles felt less threatened by the pandemic.

The theological discourse held the MOH guidelines to be irrelevant, arguing that the pandemic is God’s punishment for a lack of modesty and, therefore, only improving modesty can help. The linkage between women’s modesty and the fate of Jewish people is not a recent innovation. Rather, it is a familiar motif in the Haredi narrative, primarily based on the phrase “thanks to righteous women, Israel was redeemed from Egypt” (Sota 9). Based on various adaptations of this expression, bad events that befell the Jewish people over the years were interpreted as a punishment for the women’s inappropriate modesty (Block, 2011; Zalcberg, 2007; Zalcberg & Zalcberg, 2016); the same is true concerning the COVID-19 outbreak.

These three discourses—the value-educational, the medical, and the theological—are not detached from each other. Still, there is an affinity between them, with the common denominator of distrust regarding state institutions and authorities, in general, and the MOH, in particular.

Despite the trend of some integration into majority society in recent years (Brown, 2021), Haredi society is still characterized by its apprehension and basic suspicion and distrust toward the state, its institutions, and any sort of governmental ruling, even in time of emergency, particularly if conceived as offensive to Haredi lifestyle. Apprehension and distrust intensified during COVID-19, even among moderate Haredi circles, as crises tend to intensify and sharpen the sense of threat religious minorities feel from the majority society. At times, this might lead to emphasizing group boundaries, sometimes through hostility and violence toward others outside the community (Bavel et al., 2020), which can be seen in the conduct of the Haredi population.

Another issue that emerged from the three discourses attests to the lack of updated medical knowledge among the Haredi population regarding the sources of the pandemic and its implications (Zalcberg & Zalcberg Block, 2021). The Haredi leadership—the rabbis and the askanim—is partially responsible for this lack of knowledge. They serve as “gatekeepers” that prevent the intrusion of “external” content into the community, including essential health knowledge, on the one hand, and by bringing alternative, selective, and misleading knowledge, on the other. This aspect connects to another issue that arises from two of these discourses: the significant influence that religious leaders have on the health behaviors of believers and their conduct during illnesses and pandemics—as many participants stated that they violated MOH guidelines because they were obeying their rabbis.

The place of religious leaders in this context also stood out in the second perception, which supported the MOH guidelines, in the discourse of obedience. This discourse demonstrates that some participants who adhered to the MOH guidelines followed the instructions of their rabbis. Therefore, it seems that just as rabbis can prevent believers from adopting health-promoting behaviors, they can encourage them to embrace health-promoting behaviors and help build trust between believers and institutionalized medical authorities (Coleman-Brueckheimer et al., 2009; Peles et al., 2018; Schroeder et al., 2021). This finding is in line with previous studies that highlighted the central place of religious leaders in times of crisis, distress, and illness, including during pandemic (Ataguba & Ataguba, 2020; Heward-Mills et al., 2018; Shapiro et al., 2020).

One cannot ignore the harsh criticism that emerged in the critical discourse regarding religious leaders who advocated violating the MOH guidelines; these are criticisms to which the “Haredi ear” is not accustomed. These voices have challenged the conduct of religious authorities, and they indicate that still, for some Haredim, maintaining health—as a religious value and as a personal matter—outweighs obedience to religious authorities.

Although study participants came from the various groups and streams of Haredi society, findings show no evidence concerning the connection between the stream to which one belongs and to his or her behavior during the pandemic. This finding could attest that at the second wave of the pandemic in Israel, the majority of Haredi society expressed a quite uniform position regarding MOH guidelines, regardless of belonging to one stream or another.

The analysis of the various discourses thus provides insights into the interrelationships of the Haredi population, its leadership, and state authorities, in general, and health authorities, in particular, shedding light on the tension between the Haredi community and the government health system (Schroeder et al., 2021). These insights may indicate that the health behaviors of religious minority groups, and their conduct during pandemics, are the result of a group’s characteristics, leadership, and relations with the surrounding society. At the same time, they can point out that health behaviors can be a prism toward understanding the characteristics of a religious group and its relations with the surrounding majority society.

Research Limitations and Recommendations for Future Studies

Despite the insights that emerge from the present study, it has some limitations. First, the dynamic nature of the COVID-19 pandemic and, as a result, the changing governmental instructions intended to counter it, influences the conduct of the Haredi population, which shifted accordingly. Thus, the findings reflect the perceptions and experiences of the Haredi population during the second wave of COVID-19 in Israel, the data collection period. This may not necessarily be generalizable to the Haredi community outside of Israel, or with other religious groups, which may interact differently with different "secular" authorities and the majority society.

Second, as in any qualitative study, this study may suffer from sample bias because only those willing to participate in the study were interviewed. This potential limitation is especially relevant when researching religious communities and other minorities with strong boundaries. In addition, sample did not include participants under 25 or single. Future research should try to include these groups.

Third, the limited scope of the sample did not allow for quantitative analysis that would enable an examination of differences in participants’ perceptions across sociodemographic variables and sub-sectoral affiliation. Even though, at the moment, it seems that the current severity of COVID-19 is fading and restrictions are relaxing, a future study that includes such analysis—on a broader sample—is suggested, as a rebound of COVID-19 or emergence of any new pandemic is always present.

Fourth, the MOH’s COVID-19 vaccination campaign began in Israel after the data for this study was collected and continues today. In addition, the MOH had announced a polio outbreak in Israel in 2022 and there was a measles outbreak in 2018–2019, especially among the Haredi population, with vaccination campaigns aimed at eradication. Therefore, it is worth examining the conduct of the Haredi population regarding different vaccination campaigns since it has serious consequences for the spread of epidemics (Schroeder et al., 2021). Another interesting issue for future research is related to the intra-community home care that emerged from the “medical discourse.” Although the home care offered as an alternative to hospitalization is given subversively, and without MOH supervision, it is worth investigating its potential as an alternative model for hospitalization in order to reduce the load on hospitals and the emotional difficulties faced by a patient and his family in cases of pandemics.

This study focused on perceptions of the Haredi population regarding the MOH’s guidelines. It is worth conducting further research in the reverse direction, investigating the MOH’s perspective regarding behavior of the Haredim during the pandemic, the challenges this population posed, and how the MOH dealt with them. It also worth examining what, if any, changes have been introduced to improve communication between MOH and the Haredi community, as well as follow-up interviews among the Haredi community, in order to learn their current views regarding MOH and if they have changed.

Conclusions

The participants in the current study were Haredi individuals from various communities and streams of the Haredi society in Israel. The findings revealed five major discourses reflecting participants’ perceptions. Three discourses objected to MOH guidelines, while the other two aligned with them. The study’s findings also indicate a lack of cooperation between the Haredi population in Israel and state health authorities.

Regardless of limitations, the findings of this study provide additional insight about the interrelationships of the Haredi population and government health authorities, elucidating the tension between the two. In addition, some practical conclusions and recommendations emerge from the findings.

First, the findings attest to the necessity of incorporating cultural competence into interventions and services for the Haredi community. Health authorities and professionals should understand the Haredi population’s unique values and needs, and promote culturally adapted programs (Waitzberg et al., 2020). Increasing incorporation of the codes and the values of the target religious community are primary for accessibility of current knowledge on diseases and pandemics, and how to eradicate them.

Second, it is recommended that state and public health authorities cooperate with religious leaders (Schroeder et al., 2021) and work to strengthen the trust of the Haredi population in state institutions. Implementation of these recommendations is essential for reducing health inequalities that characterize the Haredi population in Israel and other religious minorities. During COVID-19, or any other epidemic, these recommendations have significant implications beyond a particular community. For, in the fight of a pandemic, a lack of local—or community—appropriate care carries serious consequences for the entire population.

The study also has a contribution on a global level, beyond Haredi society in Israel. It could shed light on other religious minorities dealing with tensions between theology or religious lifestyle and government demands—demonstrating a need to better understanding these communities and employ appropriately tailored messaging (Carmody et al., 2021).

Notes

As the two authors did the coding together, there was no need to a comparison between their codes.

References

Almond, G. A., Appleby, R. S., & Sivan, E. (2011). Strong religion: The rise of fundamentalisms around the world. University of Chicago Press.

Ataguba, O. A., & Ataguba, J. E. (2020). Social determinants of health: The role of effective communication in the COVID-19 pandemic in developing countries. Global Health Action, 13(1), 1788263. https://doi.org/10.1080/16549716.2020.1788263

Bavel, J. J. V., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., & Willer, R. (2020). Using social and behavioral science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behavior, 4(5), 460–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

Bayram, T., & Donchin, M. (2019). Determinants of health behavior inequalities: A cross-sectional study from Israel. Health Promotion International, 34(5), 941–952. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day054

Block, S. Z. (2011). Shouldering the burden of redemption: How the “fashion” of wearing capes developed in ultra-Orthodox society. Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, (22), 32. https://doi.org/10.2979/nashim.22.32

Block, S. Z. (2016). Religious coercion and violence against women: The case of Beit Shemesh. In Women's Rights and Religious Law (pp. 152–176). Routledge.

Brown, B. (2017). The Haredim. A guide to their beliefs and sectors. The Israeli Democracy Institute [Hebrew].

Brown, B. (2021). A society in motion: Structures and processes in ultra-Orthodox Judaism. The Israeli Democracy Institute [Hebrew].

Campbell, L., Vasquez, M., Behnke, S., & Kinscherff, R. (2010). APA Ethics Code commentary and case illustrations. American Psychological Association.

Carmody, E. R., Zander, D., Klein, E. J., Mulligan, M. J., & Caplan, A. L. (2021). Knowledge and attitudes toward COVID-19 and vaccines among a New York Haredi-Orthodox Jewish community. Journal of Community Health, 46(6), 1161–1169. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-021-00995-0

Chernichovsky, D., & Sharony, C. (2015). The relationship between social capital and health in the Haredi sector. Jerusalem: Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel.

Coleman-Brueckheimer, K., & Dein, S. (2011). Health care behaviours and beliefs in Hasidic Jewish populations: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Religion and Health, 50(2), 422–436. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-010-9448-2

Coleman-Brueckheimer, K., Spitzer, J., & Koffman, J. (2009). Involvement of Rabbinic and communal authorities in decision-making by haredi Jews in the UK with breast cancer: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Social Science & Medicine, 68(2), 323–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.10.003

DeFranza, D., Lindow, M., Harrison, K., Mishra, A., & Mishra, H. (2020). Religion and reactance to COVID-19 mitigation guidelines. American Psychologist, 76(5), 744–754. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000717

Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2011). The Sage handbook of qualitative research. Sage.

Friedman, M. (1991). Ultra-Orthodox Society: Sources trends and processes. Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies [Hebrew].

Fusch, P. I., & Ness, L. R. (2015). Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 20(9), 1408.

Heward-Mills, N. L., Atuhaire, C., Spoors, C., Pemunta, N. V., Priebe, G., & Cumber, S. N. (2018). The role of faith leaders in influencing health behaviour: a qualitative exploration on the views of Black African Christians in Leeds, United Kingdom. Pan African Medical Journal, 10, 10–11. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2018.30.199.15656

Kail, B. L., Spring, A., & Gayman, M. (2019). A conceptual matrix of the temporal and spatial dimensions of socioeconomic status and their relationship with health. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 74(1), 148–159. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gby025

Keren-Kratz, M. (2016). Westernization and Israelization within Israel’s extreme Orthodox Haredi society. Israel Studies Review, 31(2), 101–129.

Khan, S., Asif, A., & Jaffery, A. E. (2021). Language in a time of COVID-19: Literacy Bias ethnic minorities face during COVID-19 from online information in the UK. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 8(5), 1242–1248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00883-8

Leiter, E., Finkelstein, A., Greenberg, K., Keidar, O., Donchin, M., & Zwas, D. R. (2019). Barriers and facilitators of health behavior engagement in ultra-Orthodox Jewish women in Israel. European Journal of Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.26

Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage.

Malach, G., & Cahaner, L. (2021). Statistical report on Orthodox society in Israel 2020. Center for Religion, Nation and State. The Israel Democracy Institute.

Michaels, J. L., Hao, F., Ritenour, N., & Aguilar, N. (2022). Belongingness is a mediating factor between religious service attendance and reduced psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health, 61(2), 1750–1764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01482-5

Milstein, G., Palitsky, R., & Cuevas, A. (2020). The religion variable in community health promotion and illness prevention. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 48(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2019.1617519

Nadan, Y., Gemara, N., Keesing, R., Bamberger, E., Roer-Strier, D., & Korbin, J. (2019). Spiritual risk: A parental perception of risk for children in the ultra-Orthodox jewish community. The British Journal of Social Work, 49(5), 1198–1215. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcy092

Osei-Tutu, A., Affram, A. A., Mensah-Sarbah, C., Dzokoto, V. A., & Adams, G. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 and religious restrictions on the well-being of Ghanaian Christians: The perspectives of religious leaders. Journal of Religion and Health, 60(4), 2232–2249. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01285-8

Osheim, D. J. (2008). Religion and epidemic disease. Historically Speaking, 9(7), 36–37.

Peles, C., Rudolf, M., Weingarten, M., & Bentwich, M. E. (2018). What can be learned from health-related tensions and disparities in ultra-Orthodox Jewish families? Journal of Religion and Health, 57(3), 1133–1145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0590-6

Pinchas-Mizrachi, R., Zalcman, B. G., & Shapiro, E. (2020). Differences in mortality rates between Haredi and non-Haredi Jews in Israel in the context of social characteristics. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 60(2), 274–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12699

Portes, A. (1998). Social capital: Its origins and applications in modern sociology. Annual Review of Sociology, 24(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.24.1.1

Roer-Strier, D., & Sands, R. G. (2015). Moving beyond the ‘official story’: When ‘others’ meet in a qualitative interview. Qualitative Research, 15(2), 251–268. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794114548944

Satariano, B. (2020). Religion, health, social capital and place: The role of the religious, social processes and the beneficial and detrimental effects on the health and wellbeing of inhabitants in deprived neighborhoods in Malta. Journal of Religion and Health, 59(3), 1161–1174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01006-7

Schroeder, H., Numa, R., & Shapiro, E. (2021). Promoting a culturally adapted policy to deal with the COVID-19 crisis in the Haredi population in Israel. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01186-2

Shapiro, E. (2021). A protective canopy: Religious and social capital as elements of a theory of religion and health. Journal of Religion and Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01207-8

Shapiro, E., Levine, L., & Kay, A. (2020). Mental health stressors in Israel during the coronavirus pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12(5), 499. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000864

Shapiro, E., & Sharony, C. (2018). Religious and social capital and health. In E. Elgar (Ed.), Companion to social capital and health (pp. 70–88). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Stein-Zamir, C., Abramson, N., Shoob, H., & Zentner, G. (2008). An outbreak of measles in an ultra-Orthodox Jewish community in Jerusalem, Israel, 2007-an in-depth report. Eurosurveillance, 13(8), 5–6.

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. M. (1997). Grounded theory in practice. Sage.

Waitzberg, R., Davidovitch, N., Leibner, G., Penn, N., & Brammli-Greenberg, S. (2020). Israel’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic: Tailoring measures for vulnerable cultural minority populations. International Journal for Equity in Health, 19(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-01191-7

Weinberger-Litman, S. L., Litman, L., Rosen, Z., Rosmarin, D. H., & Rosenzweig, C. (2020). A look at the first quarantined community in the USA: Response of religious communal organizations and implications for public health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Religion and Health, 59(5), 2269–2282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01064-x

Weinreb, A. (2021). Excess mortality and life expectancy in Israel in 2020. Taub Center for Social Policy Studies in Israel.

Yogev, D. (2021). Community-society equilibrium: Religious organizations in the service of a secular state. Contemporary Jewry, 41(2), 369–386.

Zalcberg, S. (2007). Grace is deceitful and beauty is vain: How hassidic women cope with the requirement of shaving one’s head and wearing a black kerchief. Gender Issues, 24(3), 13–34.

Zalcberg, S. (2015). They won't speak to me, but they will talk to you: On the challenges facing a woman researcher doing fieldwork among male ultra-Orthodox victims of sexual abuse. Nashim: A Journal of Jewish Women’s Studies & Gender Issues, (29), 108–132. https://doi.org/10.2979/nashim.29.108

Zalcberg, S. (2017). The place of culture and religion in patterns of disclosure and reporting sexual abuse of males: A case study of ultra Orthodox male victims. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 26(5), 590–607.

Zalcberg, S., & Block, S. Z. (2021). COVID-19 amongst the ultra-Orthodox population in Israel: An inside look into the causes of the high morbidity rates. Contemporary Jewry, 41(1), 99–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12397-021-09368-0

Zalcberg, S., & Zalcberg, S. (2016). Body and sexuality constructs among youth of the ultra-Orthodox jewish community. In Religion, gender and sexuality in everyday life (pp. 125–140). Routledge.

Funding

This work was supported by the Shandong-Tel Aviv Joint Institute for Jewish and Israel Studies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by both authors. The first draft of the manuscript was written by both authors. They also wrote the other versions of the manuscript and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No authors of this paper have any conflicts of interest to report.

Ethical Approval

The article is based on research conducted through the auspices of the religion studies department, Tel Aviv University. This department, until only very recently, had not been sending its research proposals to a research ethics committee (mainly because it is not a social science program). Although this is now changing, the present research was already completed before the policy of the department had changed and hence this research was never presented to an ethics committee. However, both authors also teach in the school of social work at the Hebrew University and Ariel University, where all the studies do go through a research ethics committee, and the lead author teaches a graduate level course in ethics in social research, and supervises graduate students for their Master thesis, and frequently sends proposal to ethics committees of those respective institutions which have always been approved. Therefore, authors are very aware of the RULES OF ETHICS in social research, and followed them strictly in the current study, as is detailed in the article itself.

Informed Consent

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Zalcberg Block, S., Zalcberg, S. Religious Minorities’ Perceptions of Official COVID-19 Health Guidelines: The Case of Ultra-Orthodox Society in Israel. J Relig Health 62, 408–427 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01662-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01662-x