Abstract

We conducted a literature search to identify and compare definitions of the experiential dimension of spiritual pain. Key databases were searched, up to the year 2021 inclusive, for papers with a definition of “spiritual” or “existential” pain/distress in a clinical setting. Of 144 hits, seven papers provided theoretical definitions/descriptions; none incorporated clinical observations or underlying pathophysiological constructs. Based on these findings, we propose a new definition for “spiritual pain” as a “self-identified experience of personal discomfort, or actual or potential harm, triggered by a threat to a person’s relationship with God or a higher power.” Our updated definition can inform future studies in pain assessment and management.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Spirituality is becoming a focus of increasing inquiry in medicine. Currently, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) has a comprehensive strategic plan for the years 2021–2025, that delineates a commitment to research programs on “the whole person and on the integration of complementary and conventional care,” although the plan omits clear terminology about the spiritual dimension of healthcare (NCCIH, 2021, p. 1).

Important advances have been achieved by studies of the neuroscience of religious experience. Research from the past two decades provides a functional brain mapping of spiritual practices (Newberg, 2014) and includes the delineation of related regional brain activity and EEG patterns (Beauregard & Paquette, 2008; Ferguson et al., 2021; Jegindø et al., 2013), religion’s neurologic substrate (Cristofori et al., 2016) and common neural pathways for physical and social pain (Eisenberger, 2012). These advances are occurring in tandem with the recent updating of the definition of pain (Raja et al., 2020) by the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) and proposals for new and/or reorganized pain-related terms in the 11th edition of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) by IASP and the World Health Organization (Treede et al., 2019).

Spirituality-related instruments or scales continue to emerge (Büssing, 2017). For example, the Pain and Palliative Care Service at the NIH Clinical Center developed and validated a scale for psycho-social spiritual healing of individuals with life-threatening and life challenging situations, called the National Institutes of Health-Healing Experience of All Life Stressors or NIH-HEALS (Ameli et al., 2018). The latter is a welcome new measure of psycho-social spiritual healing, since there is a scarcity of scales that specifically assess spiritual practices or spiritual healing for patients with significant pain or suffering from life-threatening illnesses. The totality of the emerging data indicates a new appreciation for the potential importance of spiritual practices and highlights the need for dedicated terminology and instruments applicable to the clinical setting.

To address this unmet terminological need, we surveyed the literature in search of descriptors to define and conceptualize a new taxonomy of spiritual pain. Such terminology may help define the experience or symptoms of spiritual pain within the context of each patient's personal spirituality. Based on our findings, we aim to offer a practical and clinically applicable definition of spiritual pain in the hope of providing pathophysiological and ontological frameworks for healthcare providers.

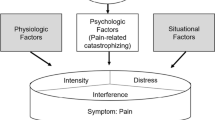

Our narrative review addresses the experiential dimension of spiritual pain, building upon existing theoretical or clinical definitions, including if and how this type of pain differs from the biological, psychological, and social dimensions of pain and/or distress. This review also addresses the extent to which spiritual pain is a component of other types of pain or whether it is a distinct entity.

At the outset of this project, an initial survey of the Hospice and Palliative Care literature revealed an evolution in thinking that described the spiritual context of an individual. Until recently, the existence of a spiritual sphere of being was implicit in research focused on the terminally ill person, with a paradigm shift emerging. The last two decades point toward the distinctiveness of such a spiritual sphere.

In this respect, data was reported from Australia, on the interventional work of staff and volunteer chaplains, employed by hospitals, church or government, dealing with pain patients (Carey et al., 2006). The authors underscore the use of pastoral skills in tackling non-physical aspects of the pain experience with exclusively religious interventions (e.g., prayer, devotions, ritual, and worship). Notably, recent research highlights the evolving nomenclature available from the World Health Organization's (WHO) Pastoral Intervention Codings (now called Spiritual Intervention Codings: WHO-SPICs), as part of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), where distinct spiritual interventions in healthcare are codified (Carey & Cohen, 2015). Without a doubt, the growing interest in the spiritual needs of patients and their caretakers is becoming more explicit, and has gradually extended into other areas of clinical care.

Early contributions to building a dedicated taxonomy for the spiritual aspects of healthcare are found in the nursing literature. In 1992, the North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) meeting reviewed the terms “spiritual distress” and “risk for spiritual distress” as well as an early nursing definition of spiritual pain as a “disruption in the principle which pervades a person’s entire being and which integrates and transcends one’s biological nature" (North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA,1992 as cited in Boss et al., 2015, p. 918). Currently, “spiritual distress” remains as a listed term in the most recent NANDA Handbook (2021) but not “spiritual pain” (Herdman et al., 2021). Caldeira et al. (2013) characterized “spiritual distress” as a condition contrary to “spiritual well-being,” which results in loss of meaning in life.

Spirituality, specifically, has been characterized in various ways; however, a clear and more focused conceptualization with an angle distinct from existential features is lacking. An early characterization of spirituality was presented in broad terms, as “a personal experiential connection with the universe that is larger than you, and is in, through and around you” (Berger and deSwaan, 2006, p.98). A few years later, the Archtone Foundation's Consensus Conference spearheaded a landmark set of guidelines seeking to integrate spiritual care as essential for optimal palliative care (Puchalski et al, 2009). The agreed upon definition at the time stated that “spirituality is the aspect of humanity that refers to the way individuals seek and express meaning and purpose and the way they experience their connectedness to the moment, to self, to others, to nature, and to the significant or sacred” (Puchalski et al, 2009, p. 887).

A more recent concept analysis of spirituality further identified three defining characteristics: “Spirituality is a way of being in the world in which a person feels a sense of connectedness to self, others, and/or higher power or nature, a sense of meaning in life, and transcendence beyond self, everyday living, and suffering” (Weathers et al., 2016, p. 93).

While we agree with portions of the above definitions, they are representative of the broad terminology which is non-descriptive of the transcendental spirituality space. A recent summary of the spirituality literature by Koenig (2018) highlights the lack of clarity and consensus in existing definitions of spirituality within a clinical context (p. 8). Therefore, we begin by re-examining and updating the concept of spirituality, which we define as “a transcendent space of being, which is non-physical and non-mental, wherein dwells a higher power, God, or universal energy with which a person seeks to enter or bask in a relationship temporarily, periodically, or permanently” (Illueca et al., 2020). It is within the context of this transcendent space that the experience or symptoms of spiritual pain may be manifested in the clinical setting. We propose that spiritual pain is a symptom because it can only be experienced and/or identified by the patient, as opposed to a sign that is assessed by an observer.

Cicely Saunders’s spearheaded the hospice movement and was early to point out the multi-dimensional nature of “total pain,” including the mental and spiritual spheres of the pain experience. This view of spiritual pain emphasizes the “unfairness” of terminal events and a “desolate feeling of meaninglessness" (Saunders, 1988). We argue that the latter concept of spiritual pain is primarily a reference to existential rather than spiritual issues. By “existential,” we mean those aspects of life that are integral to a person’s self-identity and meaning of life in the here and now. For the purposes of this paper, the existential context is distinct from the transcendental sphere of spirituality, which extends beyond life itself. Frankl describes the existential context in psychological terms as “existence itself” (i.e., the specifically human mode of being), its meaning and the search to find this meaning (Frankl, 1985, p.123).

With all the above in mind, we surveyed papers from various clinical settings reporting the experience of spiritual pain as a focus for therapeutic strategies. We summarized the prototypes of prior definitions related to the concept of spiritual pain, identified key descriptors in those early definitions, and built a new clinical definition of spiritual pain.

Methods

We performed a narrative review by searching key medical and psychology databases for papers published up to the year 2021 inclusive. Inclusion criteria were papers written in English, with a focused description or definition of “spiritual" or “existential” pain or distress, within a patient-centered or clinical context. Only primary sources were included. Exclusion criteria referred to papers mentioning spiritual pain with no clear definition in the text, or papers that provided a definition cited from another primary source.

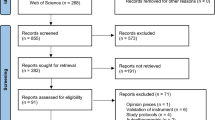

This search yielded 144 papers from Web of Science, PubMed, PsycNet, and Tufts Hirsch Health Sciences Library's JumboSearch. The searches were augmented with a manual review of citations presented within relevant papers, for a total of 18 articles of interest (Table 1). Attention focused on whether spiritual pain was studied as part of other types of pain or whether it was treated as a distinct type of distress. Papers that included work on existential distress were included if they defined or characterized spiritual pain conditions or if their definitions of existential pain or distress included a spiritual dimension.

Only primary sources were included and papers that just cited a primary source for a definition were excluded. Duplicates and papers without an explicit definition for spiritual pain were not included even if they mentioned the term. Definitions for spiritual pain, from the seven papers that met our inclusion and exclusion criteria, were tabulated, and assessed for their applicability to both spirituality and the clinical setting (Table 2). Essential descriptors were identified and noted as key components that may support a clinical definition of spiritual pain. Mixed definitions were noted as well as those that conflated existential and spiritual components. For the latter, key terms applicable only to the spirituality of the person were considered as true definitional components. Finally, based on aggregated findings, a new definition for spiritual pain is proposed.

Results

Seven papers were identified that provided limited definitions or descriptors of spiritual pain in a clinical setting including Saunders' early definition noted above. Four papers were from Western countries (USA and Sweden), one from Japan, and two papers, although written in the USA, did not specify the location of the study (Table 2). Papers in our review which indicate that “spiritual pain” is largely a self-identified experiential state separate from physical pain are discussed next, with data suggesting that spiritual pain may occur independently or in parallel with signs of somatic or existential discomfort.

Spiritual pain was studied in 57 advanced cancer patients in palliative care (Mako et al., 2006). These patients agreed to participate in study interviews given by chaplains. The operational definition of spiritual pain was “a pain deep in your soul (being) that is not physical." A total of 96% of participants reported the symptom anytime in their life and 61% during the study period. Through content analysis of patients' qualitative expression of their spiritual pain, the authors identified three distinct manifestations of the patient's experience. The reported variations included descriptions of an intrapsychic conflict (48%), or an issue in relation to the divine (38%), or an interpersonal loss/conflict (13%) as described by patients (see Table 2). In the same study by Mako et al. (2006), the authors noted that the spectrum of spiritual pain intensity was consistent across age, gender, natural history of disease, or religious/spiritual background, based on the patients' self-report. In addition, patients rated the intensity of their spiritual pain on an 11-point scale similar to the scale used to grade their physical pain on daily nursing rounds. The study did not report using any validated scales in their methods. The collected data was used to measure and estimate the correlation of spiritual pain outcomes (i.e., physical pain intensity, depression, severity of disease, and religiosity) using t test, analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Chi-square. Pertinent to our review, the only significant correlation was with depression (r = 0.43, p < 0.001), and no correlation was found with the disease stage nor with their physical pain.

Although not part of our primary series of papers, it is of interest that Delgado-Guay et al. (2011) conducted a cross-sectional prospective study of 100 patients with cancer treated at MD Anderson’s Palliative Care Clinic. Using Mako's definition (Mako et al., 2006) this group reported additional data on spiritual pain, assessing the prevalence and intensity of spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain. In this publication, as in the literature in general, religiosity refers to the adherence to ritual and ceremonial practices within an established religious dogma. The authors also looked for connections between these factors and symptoms at the time of presentation, ways of coping, and quality of life. Patients in this study identified their own spiritual symptoms. The authors found that spiritual pain was associated with lower self-perceived religiosity and lower spiritual quality of life. Patients reporting more intense spiritual pain had higher levels of anxiety, depression, anorexia, and drowsiness. The adverse effects seen in the latter group of patients extended to increased physical and emotional symptoms.

Hui et al. (2011) studied spiritual distress from the point of view of its prevalence and symptom correlates in a cohort of patients with cancer admitted to MD Anderson’s acute palliative care unit (APCU). Patient characterization included symptom assessment using the Edmonton Symptom Assessment scale (ESAS), a validated tool for use in palliative care. The ESAS assesses for feelings of well-being as well as nine symptoms: pain, fatigue, nausea, depression, anxiety, drowsiness, sleep, appetite, and shortness of breath. A total of 113 patients were included, and 44% were considered to have spiritual distress. When compared with the group without spiritual distress by univariate analysis, the most frequent features of the distress group were younger age, pain, and depression. Age and depression were also correlated by multivariate analysis.

In addition, Hui et al. (2011) reported that spiritual distress was evaluated and diagnosed by their team's chaplains, using a shortened seven item version of the original 22 item questionnaire by Nash (1990). The modified tool included seven spiritual distress domains for which a high prevalence of dysfunction was reported, in at least two of seven domains relevant to cancer care. The seven domains with a prevalence of imbalance were hope versus despair (32%), wholeness versus brokenness (27%), courage versus anxiety/dread (29%), connected versus alienated (16%), meaningful versus meaningless (15%), grace/forgiveness versus guilt (8%), and empowered versus helpless (25%).

Strang and colleagues investigated the concept of “existential pain” as understood by hospital chaplains, palliative care doctors and pain specialists (Strang et al., 2004). We included this paper because it addresses religious issues and their existential pain context, defining the latter as a metaphor of “suffering with no clear connection to physical pain” (Strang et al., 2004, p. 241). This definition is problematic because it does not exclude concurrent psychological pain as it may relate to mental health diagnoses. The latter study is valuable, however, in revealing key differences between the groups. The chaplains’ focus was on the idea of guilt and on religious issues whereas palliative doctors tended to relate existential pain to a sense of annihilation and impending separation. Pain specialist physicians responded in such a way as to indicate a sense that “life itself is painful.”

Another author (McGrath, 2002, 2003) highlighted the role of spiritual and existential beliefs as determinants of the attitudes of patients receiving palliative care. Using qualitative analyses of patient narratives, a pioneering study of differences in the experience of pain between survivors of hematological malignancies (McGrath, 2002) and hospice patients (McGrath, 2003) was conducted. First, data from the 12 cancer survivors disclosed a few distinctive features (McGrath, 2002). In the latter, the notion of spiritual pain was represented by a subjective, post-treatment painful loss of the meaning of life with an accompanying “sense of void,” “cosmic loneliness,” and “disconnection” with “normal/expected relationships.” Notably, in the survivor report, the degree of spiritual pain was sometimes indicative of a “suicidal intensity.” Additional data from the 14 hospice patients revealed comparable distinctive features (McGrath, 2003). The latter were characterized by “relational pain” resulting from “existential losses” including loss of self, personal relationships, and loss of “the expected satisfaction and meaning-making from life” but no relevant reports of suicidal intensity from the spiritual pain. In the two papers by McGrath (2002, 2003), we found a recurrence of the conflation around existential issues and spiritual pain or distress.

In this respect, the contrast between existential and spiritual pain or suffering, as it pertains to hospice and palliative care, was further explored through a literature review (Boston et al., 2011). Multiple spiritual and existential issues were identified including various dichotomies that highlighted the differences between existential and spiritual parameters: meaning and purpose in life (existential), connectedness with family and others (existential/social), worry about their loved ones (existential/social) and fear of dying (existential/spiritual). Among the existential issues considered distinct from spiritual ones are a sense of purpose, autonomy, freedom, and relational capabilities pertaining to significant others and loved ones. In contrast, the hallmark of spirituality was the self-transcendent tone in its defining traits: a sense of meaning within a religious, non-social context, recognition of a “higher source” of meaning and a relational sense of communion with the divine. The authors also found vagueness and inconsistency in the terminology and conceptualization of spiritual and existential issues.

One more paper was included that explored spiritual pain in Japanese patients with terminal cancer using a conceptual framework approach based on what the author considers the three dimensions of the human being, that is, a being founded on temporality, relationships, and autonomy (Murata, 2003). In Murata’s analysis, spiritual pain was defined as “pain caused by extinction of the being and the meaning of the self.” The latter idea is in tandem with the expected sense of isolation or social abandonment frequently noted in patients with pain (Craig et al., 2020; Eisenberger, 2012). Murata’s findings indicated that spiritual pain was characterized as a state of loss of life’s meaning, loss of identity and lack of self-worth that arose from the deep sense of losses of the dying patient (e.g., their future, their relationships, and their autonomy). The author concluded with recommendations for principles of spiritual care of terminally ill cancer patients that include recovery from this sense of loss in the various existential dimensions of the dying patient.

Discussion

The available medical literature has not yet produced a consistent or uniform definition of spiritual pain. Therefore, we propose the following:

Spiritual pain is a self-identified experience of personal discomfort, or actual or potential harm, triggered by a threat to a person’s relationship with God or a higher power. Spiritual pain becomes clinically significant when it interferes with one’s functionality and prevents one from entering the transcendent spaces of spiritual practices temporarily or permanently.

In the present review, we found widespread conflation of spiritual and existential terminology with no consistent definition of spiritual pain. Therefore, to seek a clinical definition of spiritual pain is more than an exercise in exact clinical thinking, but rather a series of complex processes that typify clinical reasoning, including the use of a “differential diagnosis” and often, a “diagnosis of exclusion.”

One specific area of diagnostic challenge stems from the interchangeable terminology used in the literature to address “existential” and “spiritual” issues. However unintentional, this overlap of meaning between existential and spiritual aspects of pain is not a new issue. As mentioned earlier, in the 1960’s, the advent of the hospice movement served to manifest the multidimensional nature of pain, including the psychological and spiritual spheres of the pain experience as interpreted by Saunders (1988) and later expanded by Boston et al. (2011). In addition, we noted that some papers came from the Hospice and Palliative Care literature, and we propose that these terms can be extrapolated to any sick patient, especially those with chronic pain or a serious medical illness at any stage, not only those in the terminal phase of their illness.

Of interest, within the context of spiritual care, it is important to note potential roadblocks to its implementation within the care plan for every patient. The barriers to psychosocial spiritual care are described in the literature based on a physician group study, considering a major challenge the fact that healthcare practitioners do not offer psychosocial spiritual care (Chibnall et al., 2004). The authors defined psychosocial spiritual care as the “aspects of care concerning patient emotional state, social support and relationships, and spiritual well-being.”

Using a qualitative group discussion format, with physicians in a variety of practice settings, Chibnall et al. (2004) identified barriers in three main areas: cultural, organizational, and clinical. In the area of cultural barriers, a recurrent finding was the marginalization of psychosocial aspects of care as “tangential” within the fundamental curriculum of medical and healthcare training. Among organizational barriers, there was a tangible degree of dissatisfaction among the medical professionals, compounded by the busyness and “workaholic norm” of physicians that get in the way of pursuing the psychosocial aspects of care in the dying patient. And concerning clinical barriers, there were communication difficulties between the evidence-based medical workstyle and the subjective nature of spiritual and psychosocial issues.

Lastly, by November 2021, the time of submitting this paper for publication, there are no new references describing spiritual pain in the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic. There is, however, emerging literature considering the importance of “spiritual care” (Ferrell et al., 2020) and “spiritual fortitude” (Zhang et al., 2021) as areas to consider in future spirituality and health research.

Limitations

There are limitations to our approach in defining spiritual pain. The available scientific terminology is problematic, without uniformity or consensus. The scarce medical literature on this topic, mainly from the Hospice and Palliative Care setting, offers fragmented prototypes of definitions and few descriptors with little or no applicable clinical criteria as summarized above in our results. Attempting to define a clinical symptom or experience that manifests itself beyond the physical and psychological spheres is a task that defies suitability for evidence-based medicine. In our quest to define spiritual pain, we recognized the need for delineating a personalized spirituality context, within which this experience may or may not be identified.

The question remains, how do we approach the spiritual dimension of healthcare within a framework of research and clinical practice? The topic of spiritual pain has a complexity that does not allow for a standard methodology to be used across various patient populations, diverse cultures, and healthcare specialties. Yet, we believe that the definition we are putting forth facilitates the dialog toward this end.

Conclusions

To embrace the idea of a spiritual dimension of care, where spiritual pain is considered a cardinal symptom, it is necessary to be open to an individualized, yet collaborative approach to patient care. Spiritual needs overlap with those of physical and mental maladies, and it is essential to endorse patient-care models in which the chaplain or pastor is a participant in the clinical team. Eventually, through the collaborative efforts of both health care and pastoral workers, it will be feasible to provide patients with relief from this real source of distress and suffering, separate from physical and psychological ailments.

The spiritual dimension of a patient is a crucial yet elusive target for intervention and, more research from more diverse clinical and cultural populations, will help to discern the best strategies to incorporate formal training in this key aspect of the holistic approach to medical care.

References

Ameli, R., Sinaii, N., Luna, M. J., Cheringal, J., Gril, B., & Berger, A. (2018). The National Institutes of Health measure of Healing Experience of All Life Stressors (NIH-HEALS): Factor analysis and validation. PLoS ONE, 13(12), e0207820. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207820

Beauregard, M., & Paquette, V. (2008). EEG activity in Carmelite nuns during a mystical experience. Neuroscience Letters, 444(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neulet.2008.08.028

Berger, A. & deSwaan, C. B. (2006). Healing pain: The innovative, breakthrough plan to overcome your physical pain and emotional suffering. Rodale Press.

Boss, L., Branson, S., Cron, S., & Kang, D. H. (2015). Spiritual pain in meals on wheels’ clients. Healthcare, 3(4), 917–932. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3040917

Boston, P., Bruce, A., & Schreiber, R. (2011). Existential suffering in the palliative care setting: An integrated literature review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41(3), 604–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.010

Büssing, A. (2017). Measures of spirituality/religiosity—description of concepts and validation of instruments. Religions, 8(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel8010011

Caldeira, S., Carvalho, E. C., & Vieira, M. (2013). Spiritual distress—Proposing a new definition and defining characteristics. International Journal of Nursing Knowledge, 24(2), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2047-3095.2013.01234.x

Carey, L. B., & Cohen, J. (2015). The utility of the WHO ICD-10-AM pastoral intervention codings within religious, pastoral, and spiritual care research. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(5), 1772–1787. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9938-8

Carey, L. B., Newell, C. J., & Rumbold, B. (2006). Pain control and chaplaincy in Australia. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 32(6), 589–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.06.008

Chibnall, J. T., Bennett, M. L., Videen, S. D., Duckro, P. N., & Miller, D. K. (2004). Identifying barriers to psychosocial spiritual care at the end of life: A physician group study. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 21(6), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1177/104990910402100607

Craig, K. D., Holmes, C., Hudspith, M., Moor, G., Moosa-Mitha, M., Varcoe, C., & Wallace, B. (2020). Pain in persons who are marginalized by social conditions. Pain, 161(2), 261–265. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001719

Cristofori, I., Bulbulia, J., Shaver, J. H., Wilson, M., Krueger, F., & Grafman, J. (2016). Neural correlates of mystical experience. Neuropsychologia, 80, 212–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2015.11.021

de Araújo Elias, A. C., Giglio, J. S., de Mattos Pimenta, C. A., & El-Dash, L. G. (2006). Therapeutical intervention, relaxation, mental images, and spirituality (RIME) for spiritual pain in terminal patients. A training program. The Scientific World Journal, 6, 2158–2169. https://doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2006.34545

Delgado-Guay, M. O., Hui, D., Parsons, H. A., Govan, K., De la Cruz, M., Thorney, S., & Bruera, E. (2011). Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain in advanced cancer patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 41(6), 986–994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.09.017

Eisenberger, N. I. (2012). The neural bases of social pain: Evidence for shared representations with physical pain. Psychosomatic Medicine, 74(2), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0b013e3182464dd1

Ferguson, M. A., Schaper, F. L. W. V. J., Cohen, A., Siddiqi, S., Merrill, S. M., Nielson, J. A., Grafman, J., Urgesi, C., Fabbro, F., & Fox, M. D. (2021). A neural circuit for spirituality and religiosity derived from patients with brain lesions. Biological Psychiatry, S0006–3223(21), 01403–01407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2021.06.016

Ferrell, B. R., Handzo, G., Picchi, T., Puchalski, C., & Rosa, W. E. (2020). The urgency of spiritual care: COVID-19 and the critical need for whole-person palliation. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(3), e7–e11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.06.034

Frankl, V. E. (1985). Man’s search for meaning. Simon and Schuster.

Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. (Eds.). (2021). NANDA International nursing diagnoses: Definitions & classification, 2021-2023. Georg Thieme Verlag.

Hui, D., de la Cruz, M., Thorney, S., Parsons, H. A., Delgado-Guay, M., & Bruera, E. (2011). The frequency and correlates of spiritual distress among patients with advanced cancer admitted to an acute palliative care unit. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 28(4), 264–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909110385917

Illueca, M., Bradshaw, Y. & Carr. D. (2020) 46th International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) World Congress on Pain, Virtual Congress (2020 September–2021, March).

Jegindø, E. M. E., Vase, L., Skewes, J. C., Terkelsen, A. J., Hansen, J., Geertz, A. W., Roepstorff, A., & Jensen, T. S. (2013). Expectations contribute to reduced pain levels during prayer in highly religious participants. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 36(4), 413–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-012-9438-9

Koenig, H. G. (2018). Religion and mental health: Research and clinical applications. Academic Press.

Mako, C., Galek, K., & Poppito, S. R. (2006). Spiritual pain among patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9(5), 1106–1113. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1106

McGrath, P. (2002). Creating a language for spiritual pain through research: A beginning. Supportive Care in Cancer, 10(8), 637–646. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-002-0360-5

McGrath, P. (2003). Spiritual pain: A comparison of findings from survivors and hospice patients. American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, 20(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1177/104990910302000109

Murata, H. (2003). Spiritual pain and its care in patients with terminal cancer: Construction of a conceptual framework by philosophical approach. Palliative Supportive Care, 1(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951503030086

Nash, R. B. (1990). Life’s major spiritual issues: An emerging framework for spiritual assessment and pastoral diagnosis. The Caregiver Journal, 7(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/1077842X.1990.10781563

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (2021). NCCIH Strategic Plan FY 2021– 2025: Mapping the Pathway to Research on Whole Person Health. National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health website. Retrieved December 2, 2021, from https://files.nccih.nih.gov/nccih-strategic-plan-2021-2025.pdf

Newberg, A. B. (2014). The neuroscientific study of spiritual practices. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 215. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00215

North American Nursing Diagnosis Association (NANDA) (1992) as cited in Boss, L., Branson, S., Cron, S., & Kang, D. H. (2015). Spiritual pain in meal on wheels’ clients. In Healthcare, 3(4), 917–932. Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare3040917

Puchalski, C., Ferrell, B., Virani, R., Otis-Green, S., Baird, P., Bull, J., Chochinov, H., Handzo, G., Nelson-Becker, H., Prince-Paul, M., Pugliese, K., & Sulmasy, D. (2009). Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: The report of the Consensus Conference. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 12(10), 885–904. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2009.0142

Raja, S. N., Carr, D. B., Cohen, Ms., Finnerup, N. B., Flor, H., Gibson, S., Keefe, F. J., Mogil, J. S., Ringkamp, M., Sluka, K. A., Song, X. J., Stevens, B., Sullivan, M. D., Tutelman, P. R., Ushida, T., & Vader, K. (2020). The revised International Association for the Study of Pain definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain, 161(9), 1976–1982. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001939

Saunders, D. C. (1988). Spiritual pain. Journal of Palliative Care, 4(3), 29–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/082585978800400306

Schultz, M., Meged-Book, T., Mashiach, T., & Bar-Sela, G. (2017). Distinguishing between spiritual distress, general distress, spiritual well-being, and spiritual pain among cancer patients during oncology treatment. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 54(1), 66–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2017.03.018

Strang, P., Strang, S., Hultborn, R., & Arner, S. (2004). Existential pain—an entity, a provocation, or a challenge? Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 27(3), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.07.003

Treede, R. D., Rief, W., Barke, A., Aziz, Q., Bennett, M. I., Benoliel, R., Cohen, M., Evers, S., Finnerup, N. B., First, M. B., Giamberardino, M. A., Kaasa, S., Korwisi, B., Kosek, E., Lavand’homme, P., Nicholas, M., Perrot, S., Scholz, J., Schug, S., Smith, B. H., Scensson, P., Vlaeyen, J.W. S., & Wang, S. J. (2019). Ýe IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD- 11). Pain, 160(1), 19–27. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384

Weathers, E., McCarthy, G., & Coffey, A. (2016). Concept analysis of spirituality: An evolutionary approach. Nursing Forum, 51(2), 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/nuf.12128

Zhang, H., Hook, J. N., Van Tongeren, D. R., Davis, E. B., Aten, J. D., McElroy-Heltzel, S., Davis, D. E., Shannonhouse, L., Hodge, A. S., & Captari, L. E. (2021). Spiritual fortitude: A systematic review of the literature and implications for COVID-19 coping. Spirituality in Clinical Practice, 8(4), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000267

Acknowledgements

Unpublished portions of this paper were written in fulfillment of the “End-of-life and Palliative Care Issues” course directed by Ms. Pamela K. Ressler, MS, RN, HNB-BC in the Pain Research, Education and Policy (PREP) program at Tufts University School of Medicine, Public Health and Professional Degree Programs, Boston, MA. The authors wish to thank Ms. Amy Lapidow, MLS, Associate Librarian Research & Instruction, at Tufts Hirsh Health Sciences Library, Tufts University School of Medicine, for technical assistance.

Funding

The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical standards

This paper complies with ethical standards.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Portions of this manuscript were presented in poster form at the 46th International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) World Congress on Pain, Virtual Congress, 2020.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Illueca, M., Bradshaw, Y.S. & Carr, D.B. Spiritual Pain: A Symptom in Search of a Clinical Definition. J Relig Health 62, 1920–1932 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01645-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01645-y