Abstract

This systematic review aimed to summarize the literature on the relationship between religiosity or spirituality (R/S) and medication adherence among patients with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and to describe the nature and extent of the studies evaluating this relationship. Seven electronic databases (PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, the Cochrane Central Library, ProQuest Theses and Dissertations, and Google Scholar) were searched with no restriction on the year of publication. The Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool was used to evaluate the methodological quality of the eligible studies. Due to the heterogeneity observed across the included studies, data synthesis was performed using a narrative approach. Nine original studies published between 2006 and 2018 were included in the review. Only a few quantitative studies have examined the relationship between R/S and medication adherence among patients with CVDs. Most studies were conducted in the USA (n = 7) and involved patients with hypertension (n = 6). Five studies showed a significant correlation between R/S (higher organizational religiousness, prayer, spirituality) and medication adherence and revealed that medication adherence improved with high R/S. The other four studies reported a negative or null association between R/S and medication adherence. Some of these studies have found relationships between R/S and medication adherence in hypertension and heart failure patients. This review showed a paucity of literature exploring the relationship between R/S and medication adherence among patients with other CVDs, such as coronary artery diseases, arrhythmia, angina and myocardial infarction. Therefore, the findings suggest that future studies are needed to explore the relationship between R/S and medication adherence among patients with other types of CVDs. Moreover, there is a need to develop interventions to improve patients’ medication-taking behaviors that are tailored to their cultural beliefs and R/S.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Religiosity is an important determinant of societal health (Zimmer et al., 2019). According to Zimmer et al. (2019), the relationship between health and religiosity is complex. Religiosity can influence the health behaviors of individuals with cardiovascular diseases (CVDs), such as coronary heart disease, hypertension and cerebrovascular disorders (Koenig, 2012). CVDs are non-communicable chronic disorders that are highly prevalent globally and are the leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The number of annual deaths due to CVDs is approximately 17.9 million. In addition, CVDs are associated with polypharmacy and medication non-adherence. Approximately 50% of patients suffering from these conditions are non-adherent to their prescribed medications (World Health Organization, 2018). For example, patients with heart failure can have poor adherence to their medications, which eventually leads to increased hospitalization and mortality (Hope et al., 2004; McMurray & Stewart, 2000). Thus, patient education, counseling, and effective communication between health care providers and patients are fundamental to improving health outcomes.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), adherence can be defined as “the degree to which the person's behavior corresponds with the agreed recommendations from a health care provider” (Sabaté, 2003). Medication non-adherence in patients with CVDs leads to increased morbidity and mortality and decreased quality of life (Shehab et al., 2016). Conversely, medication adherence plays a crucial role in enhancing health-related quality of life, especially in patients with heart failure (Huang et al., 2018). Patients with chronic diseases who are prescribed multiple medications are usually burdened with a large amount of health information to process and understand, including the importance of taking the medications (Fredericksen et al., 2018). This problem is widespread in CVD patients since they are often exposed to multiple medications. As a result, poor adherence is widely prevalent, resulting in the poor control of important risk factors, such as blood pressure and cholesterol levels, and ultimately poor treatment outcomes (Kronish & Ye, 2013). Medication adherence is affected by many factors, including but not limited to health literacy, polypharmacy, cognitive function, and adverse drug events (Gellad et al., 2011). In addition, the published literature has documented that medication adherence is affected by religious and cultural beliefs (Lin et al., 2018). However, studies investigating the association between religiosity and health outcomes, including medication-taking behaviors and adherence, are scarce.

Interest in the association between religiosity and health has increased in recent years. Some studies have shown a positive relationship between religiosity and health outcomes (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2002; Larson et al., 1989; Plante & Sharma, 2001). The interaction between religion and health has attracted many researchers to investigate the effect of religion on health. For example, Levin and Vanderpool discussed the mechanism of religion in reducing blood pressure. They found that religious practices such as prayer and meditation could induce relaxation, reduce sympathetic nervous system activity, and decrease heart rate and blood pressure (Vanderpool & Levin, 1990).

In general, a patient prefers to be treated as a whole person rather than someone suffering from a disease. “A whole person is someone who’s being has physical, emotional, and spiritual dimensions” (Koenig, 2000). Thus, neglecting these facets can make patients feel dissatisfied with their care and ultimately affect their healing process (Koenig, 2000). Consequently, the American College of Physicians recognizes the role of religiosity/spirituality (R/S) in improving health care outcomes. There are four questions suggested by the American College of Physicians that might help patients: (1) “Is faith (religion, spirituality) important to you in this illness?”; (2) “Has faith been important to you at other times in your life?”; (3) “Do you have someone to talk to about religious matters?”; and (4) “Would you like to explore religious matters with someone?” (Koenig, 2000). Both R and S are interchangeable and related in most social science research (Kiecolt-Glaser et al., 2002; Mattis, 2000). Therefore, R or S may be a beneficial topic for interventions, especially for patients with chronic diseases (Huang et al., 2018). In this review, we evaluated patients’ R and S and whether they can affect medication adherence.

Religiosity (R) has been defined as “an individual’s belief toward a divinity” (Yaghoobzadeh et al., 2018). More specifically, according to Koenig (2018), “religiosity involves beliefs, practices, and rituals related to the ‘transcendent,’ where the transcendent relates to the mystical, supernatural, or God in Western religious traditions, or to Brahman, the Ultimate Truth, the Ultimate Reality, or practices leading to enlightenment, in Eastern traditions.” Beliefs about spirits, angels, or demons are also related to religion. Koenig (2018) further mentioned that “generally, religion involves specific beliefs about life after death and rules to guide personal behaviors and interactions with others during this life.”

Religion is frequently organized and practiced within a community. However, religion can also be practiced alone and privately outside of an institution, such as personal beliefs about and the commitment to transcendent and private activities such as prayer, meditation, and scripture study. Therefore, the term religion is not limited to organized religion, religious affiliation or religious attendance. Central to its definition, however, is that religion is rooted in an established tradition that arises from a group of people with shared beliefs and practices concerning the “transcendent” (p. 13) (Koenig, 2018). Spirituality is similar to religion, even though it may be broader in some faith traditions extending beyond religion (comprising the outcomes of devout religious involvement, such as having importance and an aim in life or being intimately connected to the divine) (Koenig et al., 2012).

Hyman and Handal (2006) conducted a pilot study to clarify whether the concept of religion and that of spirituality are the same or different. Four different types of religious professionals (imams, ministers, priests and rabbis) participated in this study. The study showed that 37% of the participants agreed that “spirituality is a broader concept than religion and includes religion.” In comparison, 18% of the participants agreed that “religion is a broader concept than spirituality and includes spirituality.” Moreover, 28% of the participants said that “religion and spirituality overlap but they are not the same concept”; 17% agreed that “religion and spirituality are the same concept and overlap completely”; and no participants agreed with the concept that “religion and spirituality are different and do not overlap.” In general, religious professionals displayed similar variability, except those in the Islamic group, who agreed that religion and spirituality are the same concept and overlap completely (Hyman & Handal, 2006).

Previous studies have reported an association between R or S and CVDs (Kobayashi et al., 2015; Trevino & McConnell, 2014), indicating that a higher level of R/S leads to better CVD outcomes. One study reported a positive correlation between R/S, personal beliefs and medication adherence in outpatients with heart failure (Alvarez et al., 2016). A study in the USA found that spiritual counseling effectively controlled the complications of heart failure and improved the patients’ quality of life (Tadwalkar et al., 2014).

Several studies from different parts of the world have reported a relationship between religiosity and medication adherence among patients diagnosed with hypertension or heart failure (Abel & Greer, 2017; Alvarez et al., 2016; Black et al., 2006; Harvin, 2018; Kretchy et al., 2013; Loustalot, 2006; Park et al., 2008; Yon, 2013). However, there is conflicting evidence regarding the direction and nature of this relationship. Moreover, no comprehensive systematic review investigating the association between R or S and medication adherence among patients with CVDs has been previously published. A deeper understanding of this relationship will help design spiritually based interventions (e.g., spiritual counseling) to improve medication-taking behaviors and adherence among patients with these disorders. Hence, this systematic review was undertaken to summarize the literature on the relationship between R/S and medication adherence and to describe the nature and extent of (i.e., to characterize and quantify) the studies evaluating the relationship.

Methods

This systematic review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Item for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009).

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they measured both patients’ R/S and medication adherence. The study population consisted of patients with a range of CVDs, including but not restricted to heart failure, acute coronary syndrome, and hypertension. The review included patients of all ages and from all settings. We included only articles published in the English language. Quantitative observational studies, randomized controlled trials, and qualitative studies were included. Non-research articles or non-original research articles (e.g., editorials, reviews, and letters) were excluded from the review.

Search Strategy

A systematic literature search was conducted to identify published studies investigating CVD patients’ R/S and medication adherence. We searched the following electronic databases for eligible studies with no limit on publication year (i.e., from inception to the search date): PubMed, MEDLINE, EMBASE, Scopus, the Cochrane Central Library, ProQuest Theses and Dissertations, and Google Scholar. Searches were conducted between August 17, 2018, and September 5, 2018. In addition, manual searches of the retrieved articles’ bibliographies were conducted to identify studies that were not found in the electronic searches. Two reviewers (ME and MIMI) used Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) terms and suitable keyword synonyms related to “religiosity” and “spirituality” (including the related terms of religiousness, religious beliefs, religion, and spiritual) in combination with “medication adherence” (including the related term and synonym “medication compliance”) and “cardiovascular diseases” (including the related terms of “heart diseases”, “heart failure”, “acute myocardial infarction”, “acute coronary syndrome”, and “hypertension”). Appendix 1 shows the details of the search strings. All search results were imported into EndNote® reference management software version 8.

Study Selection Process

The included studies were first assessed by an initial review of the article title and an abstract review. Then, the full texts of the publications that met the inclusion criteria were retrieved for data extraction. Two investigators (ME and MIMI) independently conducted the study selection process and review. The reviewers met several times to discuss the study eligibility criteria. In the case of discrepancies, a third reviewer (AA) provided the final judgment regarding the inclusion or exclusion of the articles.

Data Extraction

The reviewers developed and piloted a standardized data extraction form to obtain information relevant to this systematic review. The extraction form included data on the authors, publication year, country of study, setting and population, study design, sample size, type of CVD, religion type, R/S measure, medication adherence measure, major findings, study limitations, and conclusions. In addition, detailed information regarding the outcome measures (R/S and medication adherence) was obtained, including the number of items and the description of the tool and scoring systems. The two reviewers (ME and MIMI) extracted the data, and the third investigator (AA) provided the final judgment regarding data extraction.

Quality Assessment

The authors used the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool (CCAT) to analyze and assess the methodological quality of the included studies. The CCAT is suitable for all research designs (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method designs). The eight assessed categories are the preliminaries, introduction, design, sampling, data collection, ethical issues, results, and discussion. Each category is scored from 0 to 5, where a higher score indicates a higher quality (Crowe & Sheppard, 2011a, b). A quality assessment score was calculated as a percentage for each study according to the CCAT User Guide (Crowe et al., 2011). The quality assessment was performed by two independent reviewers (ME and MIMI). The percentage agreement between the reviewers was determined using Cohen’s kappa test.

Data Synthesis

Meta-analysis could not be conducted in this systematic review due to the methodological heterogeneity of the predictor/outcome measures and the research designs across the included studies. However, according to the University of York criteria, a narrative approach to data synthesis is recommended in systemic reviews to arrive at the conclusions of studies that vary in design (Popay et al., 2006). Thus, a qualitative narrative synthesis was used to summarize the findings of this review.

Results

Study Selection

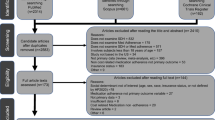

Four hundred and seven references were identified from the electronic bibliographic database searches, from which 88 duplicates were removed. After screening the titles and abstracts, only 11 studies potentially met the eligibility criteria for inclusion; full-text versions of these studies were retrieved for review. Of these, two studies were excluded due to the omission of R/S and medication adherence measures. One study was excluded because it was a thesis based on a study that was already included in the review. One additional study was included based on the search of the included articles’ reference lists. As a result, nine studies (Abel & Greer, 2017; Alvarez et al., 2016; Black et al., 2006; Greer & Abel, 2017; Harvin, 2018; Kretchy et al., 2013; Loustalot, 2006; Park et al., 2008; Yon, 2013) were included in the present systematic review. A PRISMA flowchart describing the search results and selection process is provided in Fig. 1.

Description Of Included Studies

Designs And Countries Of Study

The nine included studies were published between 2006 and 2018. Most studies (n = 7) were conducted in the USA (Abel & Greer, 2017; Black et al., 2006; Greer & Abel, 2017; Harvin, 2018; Loustalot, 2006; Park et al., 2008; Yon, 2013), while the others were performed in Ghana (Alvarez et al., 2016) and Brazil (Kretchy et al., 2013). Many of the studies (n = 6) used a cross-sectional design (Abel & Greer, 2017; Alvarez et al., 2016; Kretchy et al., 2013; Loustalot, 2006; Park et al., 2008; Yon, 2013); one study used a mixed-methods design (Greer & Abel, 2017); one utilized an experimental design (Harvin, 2018); and one used a cohort design (Black et al., 2006). The sample sizes of the studies ranged from 10 to 5302.

Participant Characteristics

The age of the study participants ranged from 19 to 85 years. The majority of participants were women in most studies. Two studies were conducted specifically among African American women (Abel & Greer, 2017; Greer & Abel, 2017), whereas three studies were conducted predominantly among males (Black et al., 2006; Greer & Abel, 2017; Park et al., 2008). In the studies performed in the USA, Brazil, and Ghana, the participants were primarily Christian, while a fourth study reported that approximately 90% of the participants were Christian, 5% were Muslim, and 1% identified with traditional religion (Kretchy et al., 2013). Three studies did not specify the religion of the participants (Alvarez et al., 2016; Harvin, 2018; Park et al., 2008). Six of the nine studies enrolled patients with hypertension (Abel & Greer, 2017; Greer & Abel, 2017; Harvin, 2018; Kretchy et al., 2013; Loustalot, 2006; Yon, 2013), while three studies involved patients with heart failure (Alvarez et al., 2016; Black et al., 2006; Park et al., 2008). A detailed description of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

Measures of Religiosity/Spirituality

A variety of R/S measures were utilized in these studies, including a measure of nine R/S questions that were developed by the investigators (Abel & Greer, 2017): organizational religious activity (ORA); non-organizational religious activity (NORA); intrinsic religiosity (IR) (Alvarez et al., 2016; Kretchy et al., 2013; Yon, 2013); positive and negative R/S coping (Greer & Abel, 2017); R/S commitment (Park et al., 2008); active and passive spiritual health locus of control beliefs (Yon, 2013); spiritual views, the extent to which these views were held, and engagement in spiritually related behaviors (Harvin, 2018); and purpose and meaning in life, inner resources, interconnectedness, and transcendence (Black et al., 2006). Different types of instruments were used to assess R/S. Two measures were used in more than one study: the Duke University Religion Index (DUREL) (Alvarez et al., 2016; Kretchy et al., 2013; Yon, 2013) and the Spiritual Perspective Scale (SPS) (Harvin, 2018; Kretchy et al., 2013). A detailed description of the tools and scoring systems that were used is presented in Table 2.

Measures of Medication Adherence

The tools used to measure medication adherence varied. These included the Repetitive Education and Monitoring for Adherence for Heart Failure (REMADHE) (Alvarez et al., 2016), adherence tools developed by the investigators (Harvin, 2018; Park et al., 2008), the JHS Medication Survey Forms (Loustalot, 2006), and the Heart Failure Compliance Questionnaire (HFCQ) (Black et al., 2006). Additionally, the 14-item Hill-Bone Compliance Scale was used in two studies (Abel & Greer, 2017; Greer & Abel, 2017), and the 4- and 8-item Morisky Medication Adherence Scale was used in two studies (Kretchy et al., 2013; Yon, 2013). A detailed description of each adherence instrument is presented in Table 3.

Study Quality Assessments

The CCAT assessed the quality of the included studies, and the scores ranged from 75 to 95%. A few of the studies addressed the representativeness of their sample or the generalizability of their findings to a broader population. Most studies reported study objectives and ethical considerations. Percentiles were used to classify the included studies into low quality (less than 76.5%), moderate quality (76.5–88%), and high quality (above 88%). Only one study (Yon, 2013) fell in the high-quality category, while the other eight studies were categorized as moderate or low in quality (Table 4). The kappa test demonstrated high agreement between the two reviewers (κ = 0.85).

Association Between Religiosity/Spirituality And Medication Adherence

Hypertension. Six studies discussed the relationship between R/S and medication adherence in patients with hypertension and highlighted the importance of addressing spiritual issues when managing hypertension to improve patients’ adherence to antihypertensive medications. Four studies (Abel & Greer, 2017; Kretchy et al., 2013; Loustalot, 2006; Yon, 2013) used a cross-sectional design, one study (Greer & Abel, 2017) used a mixed-methods design, and one study (Harvin, 2018) used a single-group pre–post-experimental design. Prayer was an important coping mechanism of religiosity and was positively associated with medication adherence among African American women with hypertension (Greer & Abel, 2017). A positive correlation was reported between three dimensions of religiosity (organized, non-organized, and intrinsic religiosity) and medication adherence. An experimental study examined faith-based educational interventions in patients with hypertension (Harvin, 2018). The study found that patients had a higher score for medication adherence after the intervention (p = 0.034). In contrast, there were nonsignificant correlations between medication adherence and attending church/religious services, praying, reading the Bible/religious material, and strength of spiritual beliefs in African American women (Abel & Greer, 2017). However, the data supported that medication adherence improved as spiritual and religious beliefs increased, although the relationship was insignificant.

Heart Failure. Three studies investigated the association between R/S and medication adherence in patients with heart failure. Two studies (Alvarez et al., 2016; Park et al., 2008) used a cross-sectional design; the third study (Black et al., 2006) utilized a cohort study design. The results of the cohort study reported that there was no relationship between the variables of spirituality and medication adherence of heart failure patients (Black et al., 2006). On the other hand, one study supported a significant association between spirituality, intrinsic religiosity and medication adherence (Park et al., 2008). The third study reported mixed findings, with some aspects of religiousness that were associated with better medication adherence, while other aspects were associated with worse medication adherence (Alvarez et al., 2016). In summary, there were mixed findings concerning whether R/S contributes positively or negatively to medication adherence.

Discussion

This study, which summarized the literature on the relationship between R/S and medication adherence and described the nature and extent of the studies evaluating the relationship in patients with CVDs, arrived at several conclusions. First, a better understanding of the relationship between R/S and medication-taking behaviors will help to develop culturally sensitive, spiritually based, and patient-centered interventions to improve medication adherence. These findings will subsequently contribute to positive health outcomes among patients with CVDs. Second, there is evidence of a positive or negative influence of religious and spiritual elements on adherence to pharmacological therapy (Badanta-Romero et al., 2018). Third, the findings suggest a significant association (positive or negative, depending on age, sex, and other confounding factors) between R/S and medication adherence in patients with CVDs.

These findings primarily apply to patients suffering from either hypertension or heart failure, since these were the only CVDs where the association was examined. Six of the included studies were conducted among patients with hypertension in the USA, while three studies were conducted among patients with heart failure. A significant association was observed concerning medication adherence with the three dimensions of religiosity reported to have a positive correlation among patients with hypertension (Kobayashi et al., 2015), where highly religious patients demonstrated a high adherence rate. Similarly, prayer was also associated with a high level of adherence among hypertensive patients (although only based on qualitative findings) (Greer & Abel, 2017). However, there was no correlation between R/S and adherence among heart failure patients in one study (Black et al., 2006). On the other hand, two studies reported significantly better adherence among those who had a higher level of R/S (Alvarez et al., 2016; Park et al., 2008).

We believed that a higher level of R/S would be associated with higher medication adherence among patients with CVDs, which might ultimately lead to better health outcomes. A recent systematic review of the relationship between R/S and QOL in CVD patients supports this research question (Abu et al., 2018).

To better understand the association between R/S and medication adherence, we need to define and differentiate between the two constructs (i.e., R/S). According to the current review, most studies did not mention the definitions of R/S or the difference between the two constructs. Some studies measured religiosity alone, some measured spirituality, and others measured both R/S. Thus, more research needs to be conducted to better understand the concepts of R and S (see Table 5).

As mentioned previously, medication adherence is vital to ensure better health outcomes. Movahedizadeh et al. (2019) found a significant positive correlation between religious beliefs and medication regimen adherence (Movahedizadeh et al., 2019). Religious beliefs and spirituality are social determinants that can increase patients’ abilities to manage their disease and encourage their recovery. Patients must believe that medication-taking behaviors are an effort toward improved health and wellness. Medicine is a means to improve health, and patients must have faith in the medicine. Therefore, religion impacts a person’s use of medication.

It is not necessary to assume that if a person has high spirituality, he or she will have high religiosity because religiosity depends on practice and commitment. “Religiosity is associated with organized worship, while spirituality is defined as the internalization of positive values” (Mattis, 2000). To assess the association between religiosity/spirituality and medication adherence, we first need to identify whether the patients believe in religiosity, spirituality or both and bring their religious beliefs and spiritual thoughts into all of their life situations (Zimmer et al., 2019). Zimmer and coworkers (2019) suggested defining the term ‘religiosity’ in the language as “a belief, which is complete obedience, being driven by a certain thought or doctrine, and walking with its passengers and in its paths. As for the concept of religiosity as a term, it is a set of principles and values, which is embraced by a community of beliefs, words, and deeds, and in many cases, these values can affect the details of our lives and decisions, including for health issues, while for the concept of spirituality, it “is concerned with the soul, values and way of thinking about the world.” Those who are religious can also be spiritual and vice versa. In summary, the difference between R and S depends on the population's cultural and religious backgrounds in addition to personal spiritual beliefs.

We found that several different tools were used to measure R/S. Most of the included studies used existing validated scales (Alvarez et al., 2016; Black et al., 2006; Greer & Abel, 2017; Harvin, 2018; Kretchy et al., 2013; Loustalot, 2006; Park et al., 2008; Yon, 2013); however, one study utilized an investigator-developed scale to measure R/S among African American women (Abel & Greer, 2017). The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL), which contains three dimensions of religiosity (intrinsic, organizational, and non-organizational religiosity), has been used in several studies (Koenig & Büssing, 2010).

Study Strengths And Limitations

To our knowledge, this systematic review is the first to examine the relationship between R/S and medication adherence among patients with CVDs. We used international guidelines to conduct these systematic reviews and searched approximately seven electronic databases. This review will ultimately create more research opportunities to deliver practical, tailored interventions to improve patient medication adherence and health outcomes.

However, there were limitations to this review. First, we excluded non-English articles, which could lead to publication bias. Second, most of the included studies had small sample sizes and were conducted among patients with hypertension, affecting the generalizability of our findings. Third, most studies were conducted in the USA, which may not sufficiently represent all types of religions or religious affiliations. Fourth, most of the studies utilized subjective instead of objective measures of adherence. Fifth, the data retrieved in this systematic review were not meta-analyzed because of the high methodological heterogeneity with large variability between studies in terms of the study design, instruments used to assess R/S, definition of outcome measures, etc. We applied a narrative approach to data synthesis in this review. Finally, according to the CCAT, the evaluation of the included studies was deemed to be of low-to-moderate quality.

Important Knowledge From The Current Review

This systematic review collected all significant evidence about the connection between religiosity, spirituality and medication adherence among patients with CVDs. In addition, it has been noticed that the problem of medication non-adherence is only seen among patients with chronic CVDs such as hypertension and heart failure. However, no study has been performed on other types of acute CVDs, such as coronary artery disease, angina, or myocardial infarction. Patients with acute CVDs are cautious about taking their medications as per health care professionals’ instructions due to disease severity and their critical condition. Hence, we found no studies that discussed the relationship between religiosity, spirituality and medication adherence among patients suffering from acute CVDs. The researchers believe that this is the reason for the dearth of literature discussing medication adherence and other acute CVDs. Our systematic review supported the results of a meta-analysis that was carried out to prove that religious involvement is associated with low mortality and improved illness (McCullough, Hoyt, Larson, Koenig, & Thoresen, 2000).

Practical Implications And Recommendations

The current systematic review will help clinicians and researchers be mindful of the gap in the literature, particularly among patients with CVDs in areas where religion is particularly important, i.e., religious/cultural traditions may strongly influence compliance with medications. Furthermore, religion and spirituality could be psychosocial factors and provide biological benefits for recovering from physical and mental disorders. Therefore, professionals should be aware of the impact that R/S has on a patient's life and incorporate these beliefs in care planning to support a holistic patient care approach. In addition, it is necessary to design interventions to promote positive coping strategies.

Future studies need to examine R/S and medication adherence in patients suffering from myocardial infarction, arrhythmia, and various levels of coronary artery disease. These findings should assist in designing comprehensive and effective interdisciplinary interventions, i.e., education and counseling programs, to address the influences of R/S on the management of chronic diseases such as CVDs. Future research in this area is greatly needed, particularly prospective studies and randomized clinical trials including patients with a more diverse range of CVDs, larger samples, and patients from different geographical locations, cultures, and religious backgrounds. In addition, understanding the relationship between R/S and medication adherence might help design spiritually integrated interventions (e.g., spiritual counseling) to improve medication-taking behaviors and adherence in patients with CVDs.

Conclusions

In summary, the current comprehensive review of the relationship between R/S and medication adherence among patients with CVDs was missing from the literature. A few studies have examined the relationship between religiosity/spirituality and medication adherence in patients with CVDs (hypertension and congestive heart failure). No studies investigating other types of CVDs were found. The studies reviewed had observational designs and found inconsistent relationships between R/S and medication adherence. The level of medication adherence among patients with CVDs (heart failure and hypertension) can be positively and negatively influenced by religious activity (prayer, intrinsic religiosity) and spirituality. Indeed, throughout history, religiosity and spirituality have been increasingly recognized as impacting health and treatment. Finally, understanding the relationship between religiosity/spirituality and medication adherence will help design educational programs and spiritually integrated interventions to improve medication-taking behaviors in patients with CVDs.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Abel, W. M., & Greer, D. B. (2017). Spiritual/religious beliefs & medication adherence in black women with hypertension. Journal of Christian Nursing, 34(3), 164–169. https://doi.org/10.1097/cnj.0000000000000333

Abu, H. O., Ulbricht, C., Ding, E., Allison, J. J., Salmoirago-Blotcher, E., Goldberg, R. J., & Kiefe, C. I. (2018). Association of religiosity and spirituality with quality of life in patients with cardiovascular disease: A systematic review. Quality of Life Research, 27(11), 2777–2797. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1906-4

Alvarez, J. S., Goldraich, L. A., Nunes, A. H., Zandavalli, M. C., Zandavalli, R. B., Belli, K. C., da Rocha, N. S., de Almeida Fleck, M. P., & Clausell, N. (2016). Association between spirituality and adherence to management in outpatients with heart failure. Arquivos Brasileiros De Cardiologia, 106(6), 491–501. https://doi.org/10.5935/abc.20160076

Badanta-Romero, B., de Diego-Cordero, R., & Rivilla-Garcia, E. (2018). Influence of religious and spiritual elements on adherence to pharmacological treatment. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(5), 1905–1917. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-018-0606-2

Black, G., Davis, B. A., Heathcotte, K., Mitchell, N., & Sanderson, C. (2006). The relationship between spirituality and compliance in patients with heart failure. Progress in Cardiovascular Nursing, 21(3), 128–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0889-7204.2006.04804.x

Crowe, M., & Sheppard, L. (2011a). A general critical appraisal tool: An evaluation of construct validity. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 48(12), 1505–1516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.06.004

Crowe, M., & Sheppard, L. (2011b). A review of critical appraisal tools show they lack rigor: Alternative tool structure is proposed. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 64(1), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.02.008

Crowe, M., Sheppard, L., & Campbell, A. (2011). Comparison of the effects of using the Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool versus informal appraisal in assessing health research: A randomised trial. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 9(4), 444–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1609.2011.00237.x

Fredericksen, R., Gibbons, L., Brown, S., Edwards, T., Yang, F., Fitzsimmons, E., Alperovitz-Bichell, K., Godfrey, M., Wang, A., Church, A., Gutierrez, C., Paez, E., Dant, L., Loo, S., Walcott, M., Mugavero,M. J., Mayer, K., Mathews, W. C., Patrick, D. L., Crane, P. K., Crane, H. M. (2018). Medication understanding among patients living with multiple chronic conditions: Implications for patient-reported measures of adherence. Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy, 14(6), 540–544. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2017.06.009

Gellad, W. F., Grenard, J. L., & Marcum, Z. A. (2011). A systematic review of barriers to medication adherence in the elderly: Looking beyond cost and regimen complexity. The American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy, 9(1), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjopharm.2011.02.004

Greer, D. B., & Abel, W. M. (2017). Religious/spiritual coping in older African American women. The Qualitative Report, 22(1), 237–260. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2017.2535

Harvin, L. (2018). Bridging the Gap: The use of a faith based intervention to improve the management of hypertension among African Americans. http://hdl.handle.net/11603/10788

Holt, C. L., Clark, E. M., Kreuter, M. W., & Rubio, D. M. (2003). Spiritual health locus of control and breast cancer beliefs among urban African American women. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 22(3), 294–299. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.22.3.294

Holt, C. L., Clark, E. M., & Klem, P. R. (2007). Expansion and validation of the spiritual health locus of control scale: factorial analysis and predictive validity. Journal of health psychology, 12(4), 597–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105307078166

Hope, C. J., Wu, J., Tu, W., Young, J., & Murray, M. D. (2004). Association of medication adherence, knowledge, and skills with emergency department visits by adults 50 years or older with congestive heart failure. American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, 61(19), 2043–2049. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/61.19.2043

Huang, J., Fang, J.-B., & Zhao, Y.-H. (2018). The relationship between quality of life and psychological and behavioral factors in patients with heart failure following cardiac resynchronization therapy. Journal of Nursing/hu Li Za Zhi, 65(3), 58–70. https://doi.org/10.6224/JN.201806_65(3).09

Hyman, C., & Handal, P. J. (2006). Definitions and evaluation of religion and spirituality items by religious professionals: A pilot study. Journal of Religion and Health, 45(2), 264–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-006-9015-z

Kiecolt-Glaser, J. K., McGuire, L., Robles, T. F., & Glaser, R. (2002). Emotions, morbidity, and mortality: New perspectives from psychoneuroimmunology. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 83–107. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135217

Kobayashi, D., Shimbo, T., Takahashi, O., Davis, R. B., & Wee, C. C. (2015). The relationship between religiosity and cardiovascular risk factors in Japan: A large–scale cohort study. Journal of the American Society of Hypertension, 9(7), 553–562. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jash.2015.04.003

Koenig, H. G. (2000). Religion, spirituality, and medicine: Application to clinical practice. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284(13), 1708–1708. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.284.13.1708-JMS1004-5-1

Koenig, H. G. (2012). Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry, 2012, 278730. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/278730

Koenig, H. G., & Büssing, A. (2010). The Duke University Religion Index (DUREL): A five-item measure for use in epidemological studies. Religions, 1(1), 78–85. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel1010078

Koenig, H., Koenig, H. G., King, D., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health. Oxford University Press.

Koenig, H. G. (2018). Religion and mental health: Research and clinical applications. Academic Press.

Kretchy, I., Owusu-Daaku, F., & Danquah, S. (2013). Spiritual and religious beliefs: Do they matter in the medication adherence behaviour of hypertensive patients? BioPsychoSocial Medicine, 7(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1751-0759-7-15

Kronish, I. M., & Ye, S. (2013). Adherence to cardiovascular medications: Lessons learned and future directions. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 55(6), 590–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2013.02.001

Larson, D. B., Koenig, H. G., Kaplan, B. H., Greenberg, R. S., Logue, E., & Tyroler, H. A. (1989). The impact of religion on men’s blood pressure. Journal of Religion and Health, 28(4), 265–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00986065

Lin, C.-Y., Saffari, M., Koenig, H. G., & Pakpour, A. H. (2018). Effects of religiosity and religious coping on medication adherence and quality of life among people with epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior, 78, 45–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2017.10.008

Loustalot, F. (2006). Race, religion, and blood pressure [Doctoral dissertation, The University of Mississippi Medical Center]. Public Health Database.

Mattis, J. S. (2000). African American women’s definitions of spirituality and religiosity. Journal of Black Psychology, 26(1), 101–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798400026001006

McCullough, M. E., Hoyt, W. T., Larson, D. B., Koenig, H. G., & Thoresen, C. (2000). Religious involvement and mortality: a meta-analytic review. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 19(3), 211–222. https://doi.org/10.1037//0278-6133.19.3.211

McMurray, J. J., & Stewart, S. (2000). Epidemiology, aetiology, and prognosis of heart failure. Heart, 83(5), 596–602. https://doi.org/10.1136/heart.83.5.596

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & Group, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Movahedizadeh, M., Sheikhi, M. R., Shahsavari, S., & Chen, H. (2019). The association between religious belief and drug adherence mediated by religious coping in patients with mental disorders. Social Health and Behavior, 2(3), 77. https://doi.org/10.4103/SHB.SHB_9_19

Park, C. L., Moehl, B., Fenster, J. R., Suresh, D., & Bliss, D. (2008). Religiousness and treatment adherence in congestive heart failure patients. Journal of Religion, Spirituality & Aging, 20(4), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/15528030802232270

Plante, T. G., & Sharma, N. K. (2001). Religious faith and mental health outcomes. In T. G. Plante & A. C. Sherman (Eds.), Faith and health: Psychological perspectives (pp. 240–261). The Guilford Press.

Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., . . . Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A product from the ESRC methods programme Version, 1, b92. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf (Access date: October 23, 2020)

Sabaté, E. (2003). Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42682/9241545992.pdf;jsessionid=1F5339078F653C3ED4268110DD49DBAF?sequence=1 (Access date: August 5, 2020)

Shehab, A., Elnour, A. A., Al Swaidi, S., Bhagavathula, A. S., Hamad, F., Shehab, O., AbuMandil, M., Abasaeed, A., Dahab, A., Kalbani, N.A., Abdulla, R., Asim, S., Erkekoglu, P., Nuaimi, S.A., Suwaidi, A. A. A., & Kalbani, N. (2016). Evaluation and implementation of behavioral and educational tools that improves the patients’ intentional and unintentional non-adherence to cardiovascular medications in family medicine clinics. Saudi Pharmaceutical Journal, 24(2), 182–188. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsps.2015.02.022

Sherbourne, C. D., Hays, R. D., Ordway, L., DiMatteo, M. R., & Kravitz, R. L. (1992). Antecedents of adherence to medical recommendations: results from the Medical Outcomes Study. Journal of behavioral medicine, 15(5), 447–468. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00844941

Tadwalkar, R., Udeoji, D. U., Weiner, R. J., Avestruz, F. L., LaChance, D., Phan, A., Nguyen, D., Bharadwaj, P., & Schwarz, E. R. (2014). The beneficial role of spiritual counseling in heart failure patients. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(5), 1575–1585. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9853-z

Trevino, K., & McConnell, T. (2014). Religiosity and religious coping in patients with cardiovascular disease: Change over time and associations with illness adjustment. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(6), 1907–1917. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-014-9897-0

Vanderpool, H. Y., & Levin, J. S. (1990). Religion and medicine: How are they related? Journal of Religion and Health, 29(1), 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00987090

World Health Organization (2018). Cardiovascular diseases. Geneva, Switzerland (Retrieved November 9, 2018, from https://www.who.int/health-topics/cardiovascular-diseases#tab=tab_1)

Yaghoobzadeh, A., Soleimani, M. A., Allen, K. A., Chan, Y. H., & Herth, K. A. (2018). Relationship between spiritual well-being and hope in patients with cardiovascular disease. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(3), 938–950. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0467-0

Yon, A. S. (2013). The influence of spirituality on medication adherence and blood pressure among older adults with hypertension. [Doctoral dissertation, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill]. https://doi.org/10.17615/ercq-8r03.

Zimmer, Z., Rojo, F., Ofstedal, M. B., Chiu, C.-T., Saito, Y., & Jagger, C. (2019). Religiosity and health: A global comparative study. SSM Population Health, 7, 100322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.11.006

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. We would like to thank American Journal of Experts and Springer Nature Author Services for editing the language of the article.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have made substantial contributions to all of the following: (1) the conception and design of the study, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data, (2) drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content, and (3) final approval of the version to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Not applicable.

Disclosure

The abstract for this paper was presented at ISPOR conference 2019 (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2019.09.1052).

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Elhag, M., Awaisu, A., Koenig, H.G. et al. The Association Between Religiosity, Spirituality, and Medication Adherence Among Patients with Cardiovascular Diseases: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J Relig Health 61, 3988–4027 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01525-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-022-01525-5