Abstract

Emerging and re-emerging diseases are responsible for recurrently affecting the health of human populations. Although people are aware of these diseases, they do not seem to adopt prophylactic methods to prevent them. Here, we propose to investigate the influence of religiosity/spirituality (R/S) on the frequency of the adoption of prophylactic behaviors and the perception of risk of vulnerability to the disease. We used dengue, which is a seasonal arboviral disease in Brazil, as a model. To measure the dimensions of religiosity/spirituality, we used the Portuguese version of the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiosity/Spirituality questionnaire. All data were obtained through a structured questionnaire that was answered online by 204 volunteers living throughout Brazil. Our results indicate that R/S is predictive of the frequency of prophylactic behaviors (p = 0.0222, R2 = 0.025) and the perception of risk of vulnerability (p < 0.05, R2 = 0.07). We argue that the effect of R/S on health occurs through the promotion of salutogenic mechanisms promoted by socialization in religious environments. This can help understand social dynamics in epidemiological crises and mitigate the influence of these diseases.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In this study, we investigated the influence of religiosity/spirituality (R/S) on the perception of health risk, as well as on the adoption of prophylactic behaviors with respect to emerging and re-emerging diseases, using dengue as our study model. An emerging infectious disease is one that appears and affects a population for the first time or has existed before but is increasing rapidly in terms of the number of new cases within a population (World Health Organization, 2014). The pressure imposed by emerging and re-emerging diseases deserves special attention because of the “fluctuation” in their frequency of occurrence (e.g., Wilder-Smith et al., 2017). Emerging infectious diseases include pathogens that have evolved recently spreading to new geographic areas and previously unrecognized or old infections that re-emerge due, for example, to lapses in public health measures (Clements & Casani, 2016). The proliferation of emerging infectious diseases is favored by human behavior and demographic factors (Clements & Casani, 2016). Despite being aware of these diseases, people do not seem to adopt prophylactic measures (Koenraadt et al., 2006; Shuaib et al., 2010), which leads to new epidemics (Gubler, 2006).

The adoption of health-related behaviors can be guided by several factors, one of which is perception of risk. The ability to detect and avoid harmful environmental conditions is necessary for the survival of all living organisms (Glendon & Clarke, 2018). Therefore, risk perception can be defined as the mechanism for detecting potentially harmful conditions (Smith et al., 2000). The perception of risk is modulated by susceptibility and perceived severity (Rimal & Morrison, 2006) and can be influenced by previous experience with the risk (Ohman, 2017). For example, studies have shown that preventive behavior in the H5N1 virus epidemic was related to a higher perceived susceptibility to infection for themselves or their families, promoting the adoption of prophylactic behaviors (Lau et al., 2007). Similar studies corroborate the findings of Lau et al. (2007) and suggest that in an infectious disease epidemic, the perception of risk related to health promotes behavior change (Brug et al., 2004; Sadique et al., 2007).

Thus, understanding how people perceive the risks to their health and the behaviors they adopt can improve our predictive capacity to direct public health actions. Allied to this, the seasonality of dengue makes this disease a good study model for risk perception and prophylactic behaviors, in addition to providing an understanding of the dynamics of this type of disease. The study of emerging and re-emerging diseases allows the development of strategies for environmental and health education (Mackey et al., 2014), as education has been essential to assisting the control of pathogens in human groups (Kelly et al., 1997; World Health Organization, 2010). Kiss et al. (2010) showed that when there are disease outbreaks, changes in health-promoting behaviors are essential to limit the spread of pathogens. If there is effective dissemination of information about the pathogen, the disease will be eliminated quickly, and the intervention measures to favor health tend to be more effective when considering the theoretical scenarios of human behavior (Glanz & Bishop, 2010).

The Evolution of Dengue in the World and Brazil

Dengue is an arbovirus that has four distinct serotypes (DENV-1, DENV-2, DENV-3, and DENV-4) transmitted by the vectors Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus (Jansen & Beebe, 2010; Marcondes & Ximenes, 2016). The first dengue epidemics were reported in the seventeenth century (Murray et al., 2013; Warkentien, 2016), with Antarctica being the only continent that has not yet experienced documented cases of dengue transmission (Brady et al., 2012).

Dengue appears to have a preferential distribution in subtropical and tropical areas, in which an estimated 3.6 to 4.1 billion people live (Messina et al., 2019). It is considered a neglected tropical disease (Huppatz & Durrheim, 2007), with an estimated infection rate of approximately 390 million people per year, causing approximately 10,000 deaths per year (Stanaway et al., 2016).

In Brazil, there are records of cases since 1845, with the first epidemics occurring between 1846 and 1848 (Pan American Health Organization, 2001). Over the years, successive epidemics have affected the Brazilian population (Fares et al., 2015). However, despite the long history of the disease in the country, dengue continues to affect the Brazilian population, with frequent and recurrent outbreaks in all states of Brazil (Brasil, 2016a, 2017, 2019a, b). In 2020, in Brazil, until the 10th week of the year, 332,000 cases of dengue were registered, with 77 deaths (Brasil, 2020).

Religion and Health

Religion is a phenomenon that arises through a “common system of beliefs and practices relating to superhuman beings within specific historical and cultural universes” (Silva, 2004). Some theories address the role of the origin and evolution of religious beliefs and practices in human evolution; however, the adaptive character of religions today is still discussed (Bourrat, 2015).

The system of practices and beliefs gives rise to two distinct events in religion: religiosity, formal or informal religious practices (Neff, 2006), and spirituality, the relationship of the individual with some transcendent force (Neff, 2006). However, religiosity and spirituality are not necessarily directly related and may vary from individual to individual in the same religious practice (Hill et al., 2000).

Levin (1996), for example, identified religious aspects as mediators of salutogenic mechanisms. Salutogenic mechanisms involve a decrease in the risk of contracting diseases and better well-being, for example, by avoiding smoking, drinking, taking illicit drugs, and having unprotected sex. In addition to influencing physical health, R/S also appears to influence mental health. Yi et al. (2006) analyzed patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and demonstrated that lower spiritual well-being was related to significant depressive symptoms. Similarly, Ironson et al. (2016) found that people with HIV who use particular spiritual coping strategies are two to four times more likely to survive than those who do not use these strategies.

The mechanisms by which R/S affects health are unclear. Evidence in the literature suggests that one of the mechanisms may be through the change and adoption of new behaviors by people. This change can be guided by the identification of health risks (Sheeran et al., 2014) and intensified by the influence of religions in promoting healthcare-related behaviors (Chatters, 2000; Cochran et al., 1992). The positive relationship between R/S and health (physical and mental) has been described in the literature by several studies (see Koenig, 2012; Moreira-Almeida et al., 2006; Powell et al., 2003). Various mechanisms of the actions of R/S on health have been discussed to understand this influence, and it has been suggested that R/S acts in different ways on mental and physical health (Aldwin et al., 2014).

The role of R/S in mental health appears to be through the promotion of a better way to face adverse situations, reducing stress (Ano & Vasconcelles, 2005), social dynamics that reduce negative emotional aspects (Nooney & Woodrum, 2002), and altruism (Saroglou, 2013). R/S also has a favorable influence on physical health by reducing stress and negative emotions and increasing social support. In physical health, the impact of R/S is given mainly because behaviors that have the potential to compromise the body’s well-being are generally discouraged (Levin, 1996; Powell et al., 2003). The modulation of these behaviors seems to be mediated by attendance at religious institutions and participation in religious services (Powell et al., 2003).

Despite evidence of the effect of R/S on prophylaxis, studies on the prophylactic phenomenon of R/S have mainly focused on sexual risk behaviors, drug use, and psychopathologies. Regarding infectious diseases, the main model studied was HIV. Therefore, there are gaps on the effect of R/S on the prophylaxis of arboviral infectious diseases, and our study bridges this gap in the literature.

Considering the premise that the adoption of health-related behaviors can be guided by several factors, such as risk perception, and that R/S has an adaptive function regarding the information on epidemiological and medical relevance, we hypothesize that R/S promotes the adoption of prophylactic behaviors in emerging diseases and the perception of risk of vulnerability in emerging diseases.

Methods

Sample Selection

The recruitment of people took place through social networks, such as Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram, from May to September 2019. Participants were invited to answer four questions on (1) religiosity/spirituality, (2) knowledge about dengue, (3) perception of risk of vulnerability, and (4) prophylactic behavior. Questionnaires were available on the online digital platform, Google Forms. To participate, volunteers had to participate be over 18 years old, residing in Brazil, and provide informed consent. We obtained a total of 204 volunteers, aged between 18 and 73 years, and including 138 women and 66 men from 17 different states in Brazil.

Religiosity/Spirituality

To collect data about R/S, the volunteers answered the Portuguese version of the Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiosity/Spirituality questionnaire (BMMRS-p). This questionnaire was created by the Fetzer Institute (Fetzer Institute & National Institute on Aging, 2003), and the Portuguese version was validated by Curcio et al. (2015) based on the work of Idler et al. (2003). The questionnaire has a total of 38 questions (one of which is categorical, to which religious denomination the volunteer belongs) that refer to 11 dimensions of R/S (see Table 1). We adapted the BMMRS-p to obtain a single score that would reflect the degree of religiosity/spirituality of an individual.

The dimensions do not have the same number of equally distributed questions, meaning that the dimensions have different minimum and maximum scores. The dimensions of the BMMRS-p can be analyzed together or separately, which allows analysis of general or specific scores for each dimension of R/S. In our study, we used the general score resulting from the sum of all responses (Table 1).

The questionnaire responses were ordered from the most frequent item to the least frequent. The answers were then ordered (except for the categorical question) on a decreasing scale so that the first response option had the highest value and the last the lowest value (Curcio, 2013). The scale assumes the maximum value of the total number of alternatives; for example, a question that has six alternatives has a maximum value of 6.

The questionnaire included questions that evaluated the frequency of negative R/S individual relationships, such as frequency of divine punishment (question 20), divine abandonment (question 21), distrust of the superior entity (question 22), criticism from the religious community (question 27), and significant loss of faith (question 30).

Therefore, for questions that assess the frequency of negative individual R/S relationships, values were ordered such that the first response option (most frequent) had the lowest value, and the last (least frequent), the highest value (Curcio, 2013). Finally, the degree of R/S was calculated using the scores of respondents on the BMMRS, determined by the sum of the scores for each dimension, ranging from 38 to 170.

Knowledge of Dengue Fever and Perception of Risk of Vulnerability

The online questionnaires on dengue consist of ten questions that asked about previous experience with the disease, knowledge about the disease, and understanding of the epidemiological stages of dengue (Appendix1). In this study, previous experience was considered concerning whether the individual had a history of the disease.

The questionnaire on the perceived risk of vulnerability (Appendix2) consists of ten questions that address the consequences of the disease on the person’s routine, control over contracting the disease, treatment, concern, understanding, perceived severity, perceived vulnerability, duration of disease, and the number of symptoms.

The response options to the questions were arranged on a scale of 0 to 5, where 0 represented the lowest evaluation category and 5 represented the largest category, except for two questions that had categorical answers regarding the duration of the disease and quantities of symptoms.

Among the ten questions, three required scale inversion for analysis purposes: perceived control (question 2), treatment efficiency (question 3), and understanding of the disease (question 5).

Among the ten questions, three required scale inversion for data analysis: perceived control (question 2), treatment efficiency (question 3), and understanding of the disease (question 5). These three questions were inverted because the scale evaluates from the smallest dimension (e.g., a score of 0 corresponding to “no control,” “inefficient,” and “I understand little”) to the most significant dimension (e.g., a score of 5 values corresponding to “total control,” “totally efficient,” and “I fully understand”). Respondents having a higher perception of risk of vulnerability would respond with a lower option, for example, "no control,” “inefficient” or “I understand little.”

Regarding questions with categorical answers, we consider that a higher perceived duration and a greater number of perceived symptoms indicate a higher perception of risk of vulnerability. The responses were then ranked increasingly from 1.

The responses of each participant were added to generate an individual risk perception vulnerability index (RPV), which can vary from 2 to 47.

Prophylactic Behavior

The questionnaire on prophylactic behavior included 11 questions (Appendix 3). Of these, eight questions dealt with the frequency of adoption of behaviors that varied from 1 (never) to 5 (always), and two dichotomous questions (yes or no) about the adoption of behaviors. The dichotomous responses were transformed into numeric values with “Yes” = 1 and “No” = 0. The responses were added to generate an index of the frequency of adoption of prophylactic behaviors (FAPB) for each volunteer, ranging from 8 to 43.

The distribution of values is shown in Table 2, where for each variable, we have the minimum and maximum values obtained by the participants, as well as the average of the measured values, the median, mode, and standard deviation.

Data Analysis

We hypothesize that R/S: (1) promotes the adoption of prophylactic behaviors and (2) promotes the perception of risk of vulnerability. To test this, we built linear mixed models (LMM) with a Gaussian distribution. We then proceeded to adjust the model by sequentially removing the variables that did not show a significant effect until we obtained the model with the lowest AIC value (Agresti, 2015).

For the first hypothesis, we adopted the frequency of adoption of prophylactic behaviors of each participant as a dependent variable and as a predictor of the index of religiosity/spirituality and previous experience. In our model, we also included the location where the volunteer resides as a random factor. The analysis of our most complex model (AIC = 1318.697) demonstrated that previous experience did not influence the frequency of participants’ adoption of prophylactic behaviors. For better adjustment of the model (AIC = 1318.33), the previous experience variable was excluded.

For the second hypothesis regarding perception, we built a model similar to the previous one, replacing the frequency of adoption of prophylactic behaviors with the perception of risk of vulnerability. The more complex model (AIC = 1267.023) demonstrated that previous experience did not influence the participants’ perception of the risk of vulnerability. After excluding the previous experience variable, we obtained a better model (AIC = 1266.64).

The LMMs (see Table 3) were constructed using the Rlme4 package (Bates et al., 2015), and the effect size of the variables was measured using the R MuMIn package (Bartoń, 2019). All tests were performed using R (version 3.5.3) (R Development Core Team, 2019), and all results with a p-value < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

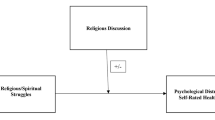

Demographic characteristics of the volunteers are presented in Table 4. The final model generated to assess the effect of R/S on prophylactic behavior (Table 3) showed a significant relationship between BMMRS-p and FABP (p = 0.0222), indicating that more religious/spiritual people adopted more frequent prophylactic behaviors (Fig. 1). The effect size of this model explained 2.5% (marginal R2 = 0.025) of the variation related to the frequency of prophylactic behaviors.

In the final model to assess the effect of R/S on risk perception (Table 3), we obtained a similar result (p < 0.05), indicating that more religious/spiritual people feel more vulnerable to dengue (Fig. 2). In this model, the effect size explained approximately 7% (marginal R2 = 0.07) of the variation in perceived vulnerability.

Discussion

Our findings suggest that R/S may have a direct influence on the behavior of epidemiological relevance, although this influence was weak. This finding reinforces the idea that there are likely other variables that can explain this phenomenon. We analyzed previous experience with dengue to control for possible bias. People who had previous contact with dengue could have a higher frequency in the adoption of prophylactic behaviors or altered perception of risk of vulnerability. However, we did not find any influence from previous experience on the adoption of behaviors or perception of risk, indicating that R/S promotes the highest frequency of prophylactic behaviors and a greater perception of vulnerability.

The health promotion mechanisms of R/S seem to be associated with a strong social component, in which there is also a promotion of cooperation/pro-sociality (Midlarsky et al., 2012; Norenzayan & Shariff, 2008; Norenzayan et al., 2016). Pro-social behavior can be defined as voluntary behavior designed to benefit individuals or groups (Eisenberg et al., 2013). For example, reviews (Ellison et al., 2010; Levin & Vanderpool, 1987) have observed that people connected to social networks who had a degree of religious involvement could benefit from salutogenic effects through religious assistance. In this sense, by identifying with each other in the religious sphere, social support among people has positive effects on their health. This effect can still be intensified, as people who attend religious services tend to have more extensive social networks (Ellison & George, 1994). Moreover, those who have a higher frequency of attendance benefit from more exceptional support than those who attend less frequently (Ellison & George, 1994). In addition, religious leaders can have a great influence on health-related decision-making and interventions (Ahmed et al., 2006; Anshel & Smith, 2014; Toni-Uebari & Inusa, 2009).

Based on the evidence in the literature, we believe that one of the possible mechanisms that can help clarify our findings is the social aspect of R/S. We believe that the support social dynamics promoted by R/S among more religious/spiritual people can favor the adoption of prophylactic behaviors in relation to emerging and re-emerging diseases. The dynamics of social support promoted by R/S could act as a promoter to learn and reinforce information on prophylactic measures related to dengue, thus leading to greater adoption of prophylactic behaviors.

The dynamics of health-protective behaviors are also linked to the perception of risks (Brewer et al., 2007). The perception of risk influences concerns about the disease (Shiloh et al., 2013). It is an important factor in determining the ability of individuals to reduce their vulnerability to risk (Williams et al., 2010). In religious/spiritual people, a phenomenon called sanctification of the bodyFootnote 1 can influence lifestyle and body care. Mahoney et al. (2005) observed that sanctification of the body was related to higher levels of health-protecting behaviors.

We believe that people who are more religious/spiritual when exposed to epidemics of emerging and reemerging diseases such as dengue may feel that the body (possessing sacred qualities) is more likely to be damaged. The fear of having the body affected by the disease can cause the perception of vulnerability to increase among more religious/spiritualized people, and as a result, there is a higher frequency in the adoption of prophylactic behaviors.

R/S and its health-promoting mechanisms contribute positively to tackling emerging and reemerging diseases, as they promote a higher frequency of adoption of prophylactic behaviors. We suggest that R/S may be a factor associated with a decrease in the frequency of emergent and reemerging diseases. Given the social mechanisms of R/S and their direct influence on health, our findings can be used to combat/decrease the forms of transmission of these diseases because more religious/spiritual people perceive these diseases as a higher risk and there is a particular propensity of people with higher R/S to perform behaviors of epidemiological relevance.

Our results have a significant contribution, as in recent years other emerging/re-emerging diseases have caused great concern among people, such as H1N1, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), HN1, Zika virus, Dengue, Ebola (Zumla & Hui, 2019), and, more recently, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic (Liu & Saif, 2020). These findings can contribute to understanding social dynamics in situations of epidemiological crisis and mitigate the effect of these diseases.

Study Limitations

We believe that the main limitation of our study was sample representativeness from Brazilian general population. Volunteers were recruited through the dissemination of the investigators' profiles on their social networks, which may contain some kind of bias on participant selection. A larger group of volunteers or intentional proportional selection could provide more robust inferences. Therefore, we suggest that future studies replicate our idea with a larger number of volunteers or control the sample representativeness utilize another re-emerging disease model.

Notes

The sanctification of the body can be understood as the attribution of sacred qualities to the body, such as the body being the dwelling of entities or a divine gift (Mahoney et al., 2005).

References

Agresti, A. (2015). Foundations of linear and generalized linear models. Wiley.

Ahmed, S., Atkin, K., Hewison, J., & Green, J. (2006). The influence of faith and religion and the role of religious and community leaders in prenatal decisions for sickle cell disorders and thalassaemia major. Prenatal Diagnosis, 26(9), 801–809. https://doi.org/10.1002/pd.1507

Aldwin, C. M., Park, C. L., Jeong, Y.-J., & Nath, R. (2014). Differing pathways between religiousness, spirituality, and health: A self-regulation perspective. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034416

Ano, G. G., & Vasconcelles, E. B. (2005). Religious coping and psychological adjustment to stress: A meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(4), 461–480. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20049

Anshel, M. H., & Smith, M. (2014). The role of religious leaders in promoting healthy habits in religious institutions. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(4), 1046–1059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9702-5

Bartoń, K. (2019). MuMIn: Multi-model inference (1.6; p. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=MuMIn). R package version. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/MuMIn/MuMIn.pdf

Bates, D., Mächler, M., Bolker, B., & Walker, S. (2015). Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. Journal of Statistical Software, https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v067.i01

Bourrat, P. (2015). Origins and evolution of religion from a Darwinian point of view: Synthesis of different theories. In T. Heams, P. Huneman, G. Lecointre, & M. Silberstein (Eds.), Handbook of evolutionary thinking in the sciences (pp. 761–780). Springer.

Brady, O. J., Gething, P. W., Bhatt, S., Messina, J. P., Brownstein, J. S., Hoen, A. G., Moyes, C. L., Farlow, A. W., Scott, T. W., & Hay, S. I. (2012). Refining the global spatial limits of dengue virus transmission by evidence-based consensus. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 6(8), e1760. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0001760

Brasil. (2016a). Boletim Epidemiológico n 38–2016 (Vol. 47, Issue Tabela 2). http://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2016/dezembro/20/2016-033---Dengue-SE49-publicacao.pdf

Brasil. (2016b). Resolução Nº 510, de 07 de April de 2016. Available on: http://conselho.saude.gov.br/resolucoes/2016/Reso510.pdf

Brasil. (2017). Boletim Epidemiológico–Semana 50. In Boletim Epidemiológico–SVS–Ministério da Saúde (Vol. 48, Issue 28). https://www.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2018/janeiro/10/2017-046-Publicacao.pdf

Brasil. (2019a). Boletim epidemiológico do Brasil no ano de 2018 (Vol. 50, Issue Tabela 1). http://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2019/janeiro/28/2019-002.pdf

Brasil. (2019b). Boletim Epidemiológico No 13 de 2019 (Vol. 50, Issue 13). http://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2019/marco/25/2019-013-Monitoramento-dos-casos-de-arboviroses-publicacao-25-03-2019.pdf

Brasil. (2020). Monitoramento dos casos de Arboviroses urbanas transmitidas pelo Aedes (dengue, chikungunya e Zika). In Boletim Epidemiológico Arboviroses (Vol. 51, Issue 24). https://portalarquivos2.saude.gov.br/images/pdf/2020/janeiro/20/Boletim-epidemiologico-SVS-02-1-.pdf

Brewer, N. T., Chapman, G. B., Gibbons, F. X., Gerrard, M., McCaul, K. D., & Weinstein, N. D. (2007). Meta-analysis of the relationship between risk perception and health behavior: The example of vaccination. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 26(2), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.26.2.136

Brug, J., Aro, A. R., Oenema, A., de Zwart, O., Richardus, J. H., & Bishop, G. D. (2004). SARS risk perception, knowledge, precautions, and information sources, the Netherlands. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 10(8), 1486–1489. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1008.040283

Chatters, L. M. (2000). Religion and health: Public health research and practice. Annual Review of Public Health, 21(1), 335–367. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.335

Clements, B. W., & Casani, J. A. P. (2016). Emerging and reemerging infectious disease threats. In Disasters and public health, pp. 245–265. Elsevier

Cochran, J. K., Beeghley, L., & Bock, E. W. (1992). The influence of religious stability and homogamy on the relationship between religiosity and alcohol use among protestants. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 31(4), 441. https://doi.org/10.2307/1386855

Curcio, Cristiane Schmann Silva. (2013). Validação da versão em Português da “Brief Multidimensional Measure of Religiousness/Spirituality ” ou “Medida Multidimensional Breve de Religiosidade/Espiritualidade”. [UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DE JUIZ DE FORA]. http://www.ufjf.br/nupes/files/2013/12/Dissertação-Validação-BMMRS-Cristiane-S-S-Curcio.pdf

Curcio, C. S. S., Lucchetti, G., & Moreira-Almeida, A. (2015). Validation of the Portuguese version of the brief multidimensional measure of religiousness/spirituality (BMMRS-P) in clinical and non-clinical samples. Journal of Religion and Health, 54(2), 435–448. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9803-1

da Silva, E. M. (2004). Religião, Diversidade e Valores Culturais: Conceitos teóricos e a educação para a Cidadania. REVER –Revista de Estudos da Religião, 2, 1–14

Eisenberg, N., Spinrad, T. L., & Morris, A. S. (2013). Prosocial development. In P. D. Zelazo (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of developmental psychology 2: Self and other. (Vol. 1). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199958474.013.0013. Oxford University Press

Ellison, C., Hummer, R., Burdette, A., & Benjamins, M. (2010). Race, religious involvement, and health: The case of African Americans. In Religion, Families and Health: Population-Based Research in the United States, (pp. 321–348)

Ellison, C. G., & George, L. K. (1994). Religious involvement, social ties, and social support in a southeastern community. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 33(1), 46. https://doi.org/10.2307/1386636

Fares, R. C. G., Souza, K. P. R., Añez, G., & Rios, M. (2015). Epidemiological scenario of dengue in Brazil. BioMed Research International, 2015, 321873. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/321873

Fetzer Institute, & National Institute on Aging (2003). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in Health Research: A report of the national working group. https://fetzer.org/sites/default/files/resources/attachment/%5Bcurrent-date%3Atiny%5D/Multidimensional_Measurement_of_Religousness_Spirituality.pdf

Glanz, K., & Bishop, D. B. (2010). The role of Behavioral Science theory in development and implementation of public health interventions. Annual Review of Public Health, 31(1), 399–418. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103604

Glendon, A. I., & Clarke, S. (2018). Human safety and risk management. Human Safety and Risk Management. https://doi.org/10.1201/b19401.CRCPress

Gubler, D. J. (2006). Dengue/dengue haemorrhagic fever: History and current status. In G. Bock & J. Goode (Eds.), New treatment strategies for dengue and other flaviviral diseases Novartis foundation symposium. Wiley.

Hill, P. C., Pargament, K. I., Hood, R. W., McCullough, M. E., Jr., Swyers, J. P., Larson, D. B., & Zinnbauer, B. J. (2000). Conceptualizing religion and spirituality: Points of commonality, points of departure. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 30(1), 51–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5914.00119

Huppatz, C., & Durrheim, D. N. (2007). Control of neglected tropical diseases. New England Journal of Medicine, 357(23), 2407.

Idler, E. L., Musick, M. A., Ellison, C. G., George, L. K., Krause, N., Ory, M. G., Pargament, K. I., Powell, L. H., Underwood, L. G., & Williams, D. R. (2003). Measuring multiple dimensions of religion and spirituality for health research. Research on Aging, 25(4), 327–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027503025004001

Ironson, G., Kremer, H., & Lucette, A. (2016). Relationship between spiritual coping and survival in patients with HIV. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 31(9), 1068–1076. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-016-3668-4

Jansen, C. C., & Beebe, N. W. (2010). The dengue vector Aedes aegypti: What comes next. Microbes and Infection, 12(4), 272–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micinf.2009.12.011

Kelly, J. A., Murphy, D. A., Sikkema, K. J., McAuliffe, T. L., Roffman, R. A., Solomon, L. J., Winett, R. A., & Kalichman, S. C. (1997). Randomised, controlled, community-level HIV-prevention intervention for sexual-risk behaviour among homosexual men in US cities community HIV prevention research collaborative. The Lancet, 350(9090), 1500–1505. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07439-4

Kiss, I. Z., Cassell, J., Recker, M., & Simon, P. L. (2010). The impact of information transmission on epidemic outbreaks. Mathematical Biosciences, 225(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mbs.2009.11.009

Koenig, H. G. (2012). Religion, spirituality, and health: The research and clinical implications. ISRN Psychiatry, 2012, 278730. https://doi.org/10.5402/2012/278730

Koenraadt, C. J. M., Tuiten, W., Sithiprasasna, R., Kijchalao, U., Jones, J. W., & Scott, T. W. (2006). Dengue knowledge and practices and their impact on Aedes aegypti populations in Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand. The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 74(4), 692–700. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.2006.74.692

Lau, J. T. F., Kim, J. H., Tsui, H. Y., & Griffiths, S. (2007). Anticipated and current preventive behaviors in response to an anticipated human-to-human H5N1 epidemic in the Hong Kong Chinese general population. BMC Infectious Diseases, 7(1), 18. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2334-7-18

Levin, J. S. (1996). How religion influences morbidity and health: Reflections on natural history, salutogenesis and host resistance. Social Science and Medicine, 43(5), 849–864. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(96)00150-5

Levin, J. S., & Vanderpool, H. Y. (1987). Is frequent religious attendance really conducive to better health?: Toward an epidemiology of religion. Social Science and Medicine, 24(7), 589–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(87)90063-3

Liu, S. L., & Saif, L. (2020). Emerging viruses without borders: The wuhan coronavirus. Viruses, 12(2), 130. https://doi.org/10.3390/v12020130

Mackey, T. K., Liang, B. A., Cuomo, R., Hafen, R., Brouwer, K. C., & Lee, D. E. (2014). Emerging and reemerging neglected tropical diseases: A review of key characteristics, risk factors, and the policy and innovation environment. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 27(4), 949–979. https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00045-14

Mahoney, A., Carels, R. A., Pargament, K. I., Wachholtz, A., Edwards Leeper, L., Kaplar, M., & Frutchey, R. (2005). The sanctification of the body and behavioral health patterns of college students. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 15(3), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327582ijpr1503_3

Marcondes, C. B., & Ximenes, M. F. (2016). Zika virus in Brazil and the danger of infestation by Aedes (Stegomyia) mosquitoes. Revista Da Sociedade Brasileira De Medicina Tropical, 49(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1590/0037-8682-0220-2015

Messina, J. P., Brady, O. J., Golding, N., Moritz, U. G., Kraemer, G. R., Wint, W., Ray, S. E., Pigott, D. M., Shearer, F. M., Johnson, K., Earl, L., Marczak, L. B., Shirude, S., Weaver, N. D., Gilbert, M., Velayudhan, R., Jones, P., Jaenisch, T., Scott, T. W., … Hay, S. I. (2019). The current and future global distribution and population at risk of dengue. Nature Microbiology, 4(9), 1508–1515. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-019-0476-8

Midlarsky, E., Mullin, A. S. J., & Barkin, S. H. (2012). Religion, altruism, and prosocial behavior: Conceptual and empirical approaches. In The Oxford handbook of psychology and spirituality, (p. 33). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199729920.013.0009. Oxford University Press

Moreira-Almeida, A., Lotufo Neto, F., & Koenig, H. G. (2006). Religiousness and mental health: A review. Revista Brasileira De Psiquiatria, 28(3), 242–250. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-44462006005000006

Murray, N. E. A., Quam, M. B., & Wilder-Smith, A. (2013). Epidemiology of dengue: Past, present and future prospects. Clinical Epidemiology, 5(1), 299–309. https://doi.org/10.2147/CLEP.S34440

Neff, J. A. (2006). Exploring the dimensionality of “religiosity” and “spirituality” in the Fetzer multidimensional measure. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 45(3), 449–459. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5906.2006.00318.x

Nooney, J., & Woodrum, E. (2002). Religious coping and church-based social support as predictors of mental health outcomes: Testing a conceptual model. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 41(2), 359–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-5906.00122

Norenzayan, A., & Shariff, A. F. (2008). The origin and evolution of religious prosociality. Science, 322(5898), 58–62. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1158757

Norenzayan, A., Shariff, A. F., Gervais, W. M., Willard, A. K., McNamara, R. A., Slingerland, E., & Henrich, J. (2016). The cultural evolution of prosocial religions. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 39, e1. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X14001356

Ohman, S. (2017). Previous experiences and risk perception: The role of transference. Journal of Education, Society and Behavioural Science, 23(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.9734/JESBS/2017/35101

Pan American Health Organization (2001). A timeline for dengue in the Americas to December 31, 2000 and noted first occurrences. http://new.paho.org/hq/dmdocuments/2010/A timeline for dengue.pdf. Pan American Health Office

Powell, L. H., Shahabi, L., & Thoresen, C. E. (2003). Religion and spirituality linkages to physical health. American Psychologist, 58(1), 36–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.36

R Development Core Team (2019). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. https://www.r-project.org/

Rimal, R. N., & Morrison, D. (2006). A uniqueness to personal threat (UPT) hypothesis: How similarity affects perceptions of susceptibility and severity in risk assessment. Health Communication, 20(3), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327027hc2003_1

Sadique, M. Z., Edmunds, W. J., Smith, R. D., Meerding, W. J., de Zwart, O., Brug, J., & Beutels, P. (2007). Precautionary behavior in response to perceived threat of pandemic influenza. Emerging Infectious Diseases, 13(9), 1307–1313. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1309.070372

Saroglou, V. (2013). Religion, spirituality, and altruism. In K. I. Pargament, J. J. Exline, & J. W. Jones (Eds.), APA handbook of psychology, religion, and spirituality (Vol 1): Context, theory, and research. American Psychological Association.

Sheeran, P., Harris, P. R., & Epton, T. (2014). Does heightening risk appraisals change people’s intentions and behavior? A meta-analysis of experimental studies. Psychological Bulletin, 140(2), 511–543. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033065

Shiloh, S., Wade, C. H., Roberts, J. S., Alford, S. H., & Biesecker, B. B. (2013). Associations between risk perceptions and worry about common diseases: A between- and within-subjects examination. Psychology and Health, 28(4), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2012.737464

Shuaib, F., Todd, D., Campbell-Stennett, D., Ehiri, J., & Jolly, P. E. (2010). Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding dengue infection in Westmoreland Jamaica. The West Indian Medical Journal, 59(2), 139–146.

Smith, K., Barrett, C. B., & Box, P. W. (2000). Participatory risk mapping for targeting research and assistance: With an example from East African pastoralists. World Development, 28(11), 1945–1959. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00053-X

Stanaway, J. D., Shepard, D. S., Undurraga, E. A., Halasa, Y. A., Coffeng, L. E., Brady, Ol. J., Hay, S. I., Bedi, N., Bensenor, I. M., Castañeda-Orjuela, C. A., Chuang, T.-W., Gibney, K. B., Memish, Z. A., Rafay, A., Ukwaja, K. N., Yonemoto, N., & Murray, C. J. L. (2016). The global burden of dengue: An analysis from the global burden of disease study 2013. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, 16(6), 712–723. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)00026-8

Toni-Uebari, T. K., & Inusa, B. P. D. (2009). The role of religious leaders and faith organisations in haemoglobinopathies: A review. BMC Blood Disorders, 9(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2326-9-6

Warkentien, T. (2016). Dengue fever: Historical perspective and the global response. Journal of Infectious Diseases and Epidemiology, https://doi.org/10.23937/2474-3658/1510015

Wilder-Smith, A., Gubler, D. J., Weaver, S. C., Monath, T. P., Heymann, D. L., & Scott, T. W. (2017). Epidemic arboviral diseases: Priorities for research and public health. The Lancet. Infectious Diseases, 17(3), e101–e106. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30518-7

Williams, L., Collins, A. E., Bauaze, A., & Edgeworth, R. (2010). The role of risk perception in reducing cholera vulnerability. Risk Management, 12(3), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1057/rm.2010.1

World Health Organization (2010). Control of the leishmaniases. In World Health Organization Technical Report Series (Issue 949). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44412/WHO_TRS_949_eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

World Health Organization (2014). R.O. for S.-E. A. A brief guide to emerging infectious diseases and zoonoses. http://www.who.int/iris/handle/10665/204722

Yi, M. S., Mrus, J. M., Wade, T. J., Ho, M. L., Hornung, R. W., Cotton, S., Peterman, A. H., Puchalski, C. M., & Tsevat, J. (2006). Religion, spirituality, and depressive symptoms in patients with HIV/AIDS. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(S5), S21–S27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00643.x

Zumla, A., & Hui, D. S. C. (2019). Emerging and reemerging infectious diseases: Global overview. Infectious Disease Clinics of North America, 33(4), 13–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.idc.2019.09.001

Acknowledgements

This study was financed in part by the Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior—Brasil (CAPES)—Finance Code 001. Contribution of the INCT Ethnobiology, Bioprospecting, and Nature Conservation, certified by CNPq, with financial support from FACEPE (Foundation for Support to Science and Technology of the State of Pernambuco—Grant number: APQ-0562-2.01/17). Thanks to CNPq for the productivity grant awarded to UPA. Thanks to Dr. Leonardo Chaves for your help with the statistical analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest exists.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals

The project was executed following the requirements of the current legislation (Resolution No. 510 of April 07, 2016, of the National Health Council) (Brasil, 2016b).

Informed Consent

All volunteers who agreed to participate in this research signed the free and informed consent form, authorizing the collection, use, and publication of data.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Oliveira, D.V.B., da Silva, J.F., de Sousa Araújo, T.A. et al. Influence of Religiosity and Spirituality on the Adoption of Behaviors of Epidemiological Relevance in Emerging and Re-Emerging Diseases: The Case of Dengue Fever. J Relig Health 61, 564–585 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01436-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01436-x