Abstract

Objectives

This paper examines the impact of local economic activity on criminal behavior. We build on existing research by relaxing the identification assumptions required for causal inference, and estimate the impact of local economic activity on recidivism.

Methods

We use the fracking boom as a source of credibly exogenous variation in the economic conditions into which incarcerated people are released. We replicate and extend existing instrumental variables analyses of fracking on how many released offenders return to state prison seperately from aggregate crime and arrests.

Results

Our instrumental variables estimates imply that a ten thousand dollar increase in the value of per capita production is associated with a 2.8% reduction in the 1-year recidivism of ex-offenders at the county level. Improved labor market conditions, specifically an increase in wages for young adults, may explain a non-negligible fraction of the reduction in recidivism associated with economic booms. In contrast, we replicate existing work finding that fracking increased aggregate measures of crime and arrests.

Conclusion

Increased economic opportunity appears to have a different impact of overall crime than on recidivism. This suggests that the relationship between economic opportunity and offending may be conditioned by local social ties. Further research examining how social connections and labor markets affect individual criminal behavior is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

One of the legacies of the United States experiment with mass incarceration in the 1980s and 1990s is that an increasingly large number of people are now leaving confinement and reentering general society. According to the National Prisons Statistics, in 2019 over 600 thousand people were released from state or federal prison, roughly 30 thousand more than the number of people entering those same facilities. Many of those released will continue to engage in crime; around 40% of people released from prisons in 2005 were arrested at least once during their first year of release (Alper and Markman 2018). In contrast to the scope of the problem, there is currently limited casual evidence on what sorts of policy interventions can successfully reduce the probability that someone leaving incarceration will be re-incarcerated (Nagin et al. 2009; Doleac 2020). This is noticeably different than the evidence on offending more generally, where there is a fair amount of evidence on “what works” to reduce crime (e.g., Nagin 2013; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine 2018). In this paper, we combine insights from two strands of literature to provide new estimates of the role of labor market opportunities on recidivism, exploiting credibly causal variation in local economic activity generated by the fracking boom of the mid-2000s. We find evidence that increased economic activity reduced recidivism, despite being associated with an increase in overall crime and arrests at the county level.

A large literature, spanning criminology, economics, and sociology, examines the role of an individual’s economic opportunity in recidivism. Employment is consistently found to be a strong correlate of desistance (Bushway and Reuter 2001; Laub and Sampson 2001; Doleac 2020), and individuals who are released into areas where actual or perceived labor demand is higher are less likely to recidivate (Raphael and Winter-Ebmer 2001; Corman and Mocan 2005; Galbiati et al. 2021; Yang 2017; Schnepel 2018; Agan and Makowsky 2021).

At the same time, experimental evaluations of job placement and job training for formerly incarcerated people are substantially more mixed. There are many credible potential explanations for this. Discrimination against ex-offenders in the labor market may dampen the ability of trained, qualified, formerly incarcerated people to be hired (Pager 2011; Agan and Starr 2018). Many experimental evaluations have low statistical power, which is particularly problematic if the true average impact of job training programs on wages and employment is small (Doleac 2020). Requiring participation in even “one stop” re-entry programs, particularly if they are ineffective, may inadvertently create an additional task that formerly incarcerated people must complete to comply with parole terms, potentially crowding out more effective, individually driven, job search efforts (Denver et al. 2017; Schnepel 2018).

We contribute to this literature by exploring the recidivism of people who, rather than being required to participate in a training or placement program, are simply released into economies with a high demand for relatively low skilled labor. While unexplained variation in labor market conditions on release, previously studied in Schnepel (2018) and Yang (2017) may not necessarily be correlated with individual characteristics, in this paper we know the precise reason for the increased economic activity. As a result, we require a weaker identifying assumption than the existing research evaluating the impact of economic conditions on recidivism.

The increase in economic activity we analyze is due to the growth of the oil and gas industry in certain parts of the United States. This growth was the result of technological developments, which lowered the cost of extracting oil and natural gas from underground shale formations through hydraulic fracturing or “fracking.” The increased revenue for energy companies also appears to have had some positive spillover effects for local residents; fracking in areas that sit over shale formations, which are overwhelmingly in rural areas and relatively small cities, has been estimated to generate an average wage increase of around $0.20 for every dollar of new production (Feyrer et al. 2017).

We identify the causal effects of this local economic activity on recidivism, measured using the National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP). Our central modeling approach replicates IV strategy developed by Feyrer et al. (2017) to estimate the causal impact of fracking revenue on a variety of socioeconomic outcomes. The approach involves instrumenting for the amount of fracking revenue in one county with the average annual revenue generated by the larger “shale play” (an area sharing particular geographic and geological properties) where the county is located. Intuitively, we estimate whether people are more or less likely to return to prison when they are released into a community located on top of a shale play that happens to be more, or less, productive in that year. Under the assumptions that (1) changes in the value of a shale play are driven primarily by technological advances in drilling, (2) each county contributes only a small fraction of the total shale play revenue, and (3) there is no plausible reason that advancement in drilling technology is correlated with an individual’s propensity to recidivate, except through the net impact of that technology on the local economy, our estimates can be interpreted as the causal impact of economic activity on recidivism. To facilitate comparisons with existing research (specifically Schnepel 2018), we focus on 1-year recidivism rates to emphasize the role of economic activity in both desistance from crime and a person’s ability to comply with parole conditions, although the results do not change in a meaningful way when we examine return to prison over longer time horizons.

We estimate that a ten thousand dollar increase in the per capita value of energy production is associated with a 2.8% reduction in the 1-year recidivism of ex-offenders relative to those released into other counties or at different times, an effect only slightly larger than the 2% reduction in recidivism associated with a one standard deviation increase in construction jobs identified in Schnepel (2018). This suggests that economic activity generated by fracking resulted in almost 2,250 fewer offenders returning to prison (within 1 year of release) between 2006 and 2014.

Of course, economic activity itself can generate a wide array of socioeconomic changes, and each individual change may influence criminal behavior through a unique mechanism. Our single economic shock cannot separately identify exactly what about increased economic activity translates into more successful re-entry. However, we do explore the potential channels through which economic activity leads to lower recidivism in counties experiencing fracking booms, ranging from post-fracking compositional changes in the population to wage growth. We find that increased wages likely explain a non-negligible fraction of our findings.

Our results are consistent with Street (2019), which finds that long-time residents of areas in North Dakota that benefited from fracking are less likely to have criminal charges filed against them in court. We conclude that the findings of Street (2019) likely hold outside of the specific North Dakota context, and relate to recidivism as well as general offending by established residents. Of course, like Street (2019), our local average treatment effects are estimated in the more rural places where fracking has primarily occurred, but the similarity of our results to Schnepel (2018) suggest that the relationship between economic opportunity and returning to prison is independent of how urbanized a place is.

This paper also contributes to a growing literature that specifically investigates the relationship between hydraulic fracturing activity and economic and social outcomes (Feryer et al. 2017; James and Smith 2017; Kearney and Wilson 2018; Bartik et al. 2019; Street 2019; Cascio and Narayan 2022). Notably, a recent review of 25 studies of fracking and crime concluded that the positive relationship between increased production and crime is, essentially, undisputed (Stretesky and Grimmer 2020). We are able to replicate this finding in our specific context, and conclude that our findings complicate this fracking-crime relationship by documenting a relationship between the economic activity generated by hydraulic fracturing activity and recidivism which differs from the average impact on crime.

While speculative, our results are consistent with evidence that local community ties not only condition, but potentially invert, the relationship between economic booms and individual criminal behavior. Alternately, our results can be interpreted as identifying potential heterogeneity in the relationship between community ties and criminal behavior.Footnote 1

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses hydraulic fracturing. Section 3 describes the data, and Sect. 4 the empirical methodology. Section 5 presents the results and several robustness checks. Our conclusions are provided in Sect. 6.

Background

In order to identify the impact of local economic conditions on recidivism, we exploit variation in the oil and gas production generated by the development of hydraulic fracturing. This technological innovation created a sharp increase in the amount of economic activity in regions with the geographic features conducive to oil and gas extraction. We can use the timing of this technological innovation to better understand the causal impact of economic growth on recidivism, as long as this technological change in the ability of energy companies to extract oil and gas from the geographic formations underlying a released individual’s hometown is not related to when that individual is released from prison and their underlying propensity to recidivate.

Fracking is a well stimulation technique involving the high-pressure injection of water, sand and chemicals into low permeability shale formations that contain large reservoirs of oil and natural gas. The process of fracking begins by drilling a well into shale, and inserting a casing pipe into the well bore. Fluid is then injected into the shale at high pressure, creating cracks in the rock. The fluid itself contains material called proppants, typically sand, which then hold the fractures open and enable oil and gas to escape to the surface through the casing pipes. The widespread adoption of horizontal drilling, which involves drilling vertically until a target depth is reached, and then drilling several thousand feet further horizontally into a rock formation, has broadened the scale and scope of hydraulic fracturing.

Throughout the text, we refer to shale formations in the form of “basin” and “play.” A shale basin, usually covering hundreds of square miles, is a bowl-shaped area containing multiple oil and natural gas resources. A shale play is part of a basin with particular geographic and geological properties that allow for drilling and production to actually occur.Footnote 2

The development of hydraulic fracturing, in conjunction with horizontal drilling, has dramatically increased domestic oil and gas production over the last two decades. It now accounts for slightly more than 50% of total oil production (4.3 million barrels per day) and nearly 70% of gas production in the U.S. (53 billion cubic feet per day). More than 300,000 new wells were hydraulically fractured between 2000 and 2014 (U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2016a and 2016b). The oil and gas industry extracted around $400 billion worth of new production and is estimated to have generated over 600,000 new jobs over the period from 2005 to 2012 (Feyrer et al. 2017).

The first order effect of fracking is to increase the demand for labor in extraction-related jobs, but there are substantial spillovers associated with this activity as well. In particular, existing research has documented a substantial increase in population, especially young single men, which could lead to increased demand in other industries, particularly in the retail, accommodation, and food sectors (Munasib and Rickman 2015). Feyrer et al. (2017) also show that 20% of the overall increase in employment was in the mining sector, 30% was in the transportation sector and the remaining was in sectors not directly related to extraction. This increase in overall economic activity means that people, including the formerly incarcerated, may not have to directly work in extraction in order to have their incentives and opportunities from fracking.

Data

The data for this study are compiled from several different sources. The first one is the administrative records on prisoner admissions and releases collected by the Bureau of Justice as part of the National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP). NCRP is a voluntary program, beginning in 2000 with the participation of 15 states. It has grown steadily over time, and in our sample forty-three state Departments of Correction participate.Footnote 3 NCRP data include basic information such as each prisoner’s gender, race/ethnicity, and educational attainment, as well as state prison admittance and release dates. In addition, for each prison spell, the data provide the reason why the prisoner initially entered into custody (their “original offense”) and the reason why the prisoner was released. Unique state identification numbers allow us to track all returns to custody over time, as long as re-offending takes place within the same state – this is generally considered to capture over 90% of reoffending (Raphael and Weiman 2007).Footnote 4 The NCRP data also contain information on county of conviction, which we use as a proxy for each offender’s post-release location.Footnote 5

We impose three restrictions on our sample. First, we limit our attention to the first time an offender appears in the data and explore criminal activities onwards.Footnote 6 Thus, each offender can only contribute once to our estimate of recidivism. Second, we drop offender-level observations if information on county of conviction and date of admittance or release are missing (2.3% and 12% of the first time offender sample, respectively). Finally, we drop observations if the reason for release code from prison is death (0.4% of the first time offender sample).

The data on hydraulic fracturing activity are drawn from Feyrer et al. (2017) and include the total value (in 2014 dollars) of oil and natural gas extracted from new wells between 2005 and 2014, by county. Monthly information on value of oil and gas extracted from each well is obtained from DrillingInfo.Footnote 7 We link NCRP data with data on hydraulic fracturing activity using county level identifiers. Appendix Table 7 presents the states and years with NCRP data available over the period between 2005 and 2014.Footnote 8 We also include county level information on demographic, economic and other related variables from the Census (county level population, education, and race), the IRS Tax Statistics (county level immigration), the U.S. Enviromental Protection Agency (county level air pollution) and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (wage and employment estimates).

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics on the more than 2.5 million unique offenders in our sample. As shown in the first column of Table 1, more than 11% of all offenders return to state prison within 1 year of release. For these first time offenders, the rate of return to prison within 3 year is around 25%. An overwhelming majority of prisoners are male (86%). White offenders comprise 53% of all prisoners while Black offenders make up more than one-third. A large fraction (50%) did not graduate from high school. The average age at the time of release is 34 and actual time served in prison is around 2 year. The most serious convictions associated with original incarceration spell are somewhat evenly distributed across violent, property and drug- related offenses. Finally, around 28% of the prisoners in the effective sample are released after serving their full sentence, meaning they are not subject to parole oversight. Column 3 of Table 1 provides the same statistics for inmates who return to prison within 1 year of release. Relative to the whole sample, recidivists are slightly more likely to be male and Black and have fewer years of education. Recidivism is more likely for people who were originally convicted of property crimes, and are lower among those who served their full sentence.

Table 2 provides descriptive statistics, at the county-year level, for the 2653 unique counties in the effective sample. Across counties, the average 1-year recidivism rate is around 12%. The average value of oil and natural gas production is $1600 per year, per capita, with a noticeable large dispersion around that mean; the standard deviation is more than $13,600.Footnote 9 On the 365 counties located in major shale plays, the average value of production is $17,000, with a standard deviation of $73,500. Figure 1 displays the average value of oil and natural gas production for each county, per person, matched with the NCRP data from 2005 to 2014.Footnote 10 Hydraulic fracturing activity is concentrated in a number of major shale plays, covering the states of North Dakota, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Texas, West Virginia and Wyoming. Figure 2 also plots these major shale plays, along with basins, in the U.S. Note that these 14 shale plays, located within 12 basins, generate almost all domestic oil and natural gas production (Drilling Productivity Report of the U.S. Energy Information Administration-various years).Footnote 11

Average value per capita from oil and natural gas production (2005–2014). NOTES: Forty contiguous states with available National Corrections Reporting Program (NCRP) data over the span from 2005 to 2014 are plotted in the map. States that did not participate in NCRP and those states with no available data over the time span are omitted from the map. Average new values per capita from oil and natural gas production are in 2014 dollars and are drawn from Feyrer et al. (2017)

Major shale plays and shale basins in the contiguous United States. NOTES: Major shale plays and shale basins in the contiguous United States are drawn from the drilling productivity report (various years) of the U.S. Energy Information Administration. These shales plays (basins) are Bakken (Williston), Barnett (Fort-Worth), Eagle Ford (Western Gulf), Fayetteville (Arkoma), Haynesville (TX-LA-MS Salt), Marcellus (Appalachian), Niobrara–Denver (Denver), Niobrara-Greater Green River (Greater Green River), Niobrara-Powder River (Powder River), Permian All Plays (Permian), Utica (Appalachian), Woodford–Anadarko (Anadarko), Woodford-Ardmore (Ardmore) and Woodford–Arkoma (Arkoma). The NCRP data is not available for Arkansas during our analysis period and therefore, Fayetteville is excluded in the analysis

Methodology

To evaluate the effect of hydraulic fracturing on recidivism, we begin by estimating the following model, which essentially combines Schnepel (2018) with Feyrer et al. (2017)

where \(R_{czt}\) is the natural log of the number of former inmates returning to prison within a year from each release cohort t in county c and commuting zone z. \(New~Value_{zt-1}\) is the lagged annual value per capita of the oil and natural gas extracted from new wells at commuting zone level z. The variable of interest is defined as “new value” because it solely represents the value of production from new wells in any given year. \(X_{ct}\) is a vector of observed characteristics (e.g., proportion of the county population who are female, white, black and Hispanic, proportion of the county population with high school degree or less and county population), \(\eta _{c}\) and \(\lambda _{t}\) denote county and release cohort (time) fixed effects, respectively and finally, \(\epsilon _{czt}\) is the error term.Footnote 12 The coefficient \(\beta _{1}\) shows the effect of hydraulic fracturing activity on 1 year recidivism (we report the effect for 3 year recidivism in Section 5.1). In this specification, we are assuming that each additional ten thousand dollars of oil and gas revenue, per person, changes the number of people who recidivate by (\(\beta _{1}*100)\)%.

We lag fracking revenue by 1 year to capture the effect of an increase in the revenue generated by fracking on employment opportunities in the energy industry (a direct effect), as well as multiplier (indirect) impacts on economic opportunities more generally. Note also that aggregating the value of oil and gas production to the commuting zone level incorporates potential spillovers across counties, safeguarding against contamination in the estimated effects that may arise because of failing to account for spatial propagation of fracking activity (e.g., offenders working in nearby counties with higher fracking activity).Footnote 13 Our main findings are similar when new value per capita is defined at the county level or if we replace the lagged value of new production with its current value. Finally, county level release cohort size is included as a right hand side variable in all specifications throughout the paper (unless otherwise stated).

Straightforward estimation of Equation (1) via OLS provides an unbiased coefficient estimate of \(\beta _{1}\) if the value of hydraulic fracturing activity is exogenously determined. However, similar to the broader issues raised in Feyrer et al. (2017), there are many potential unobserved factors that could affect recidivism and are also correlated with hydraulic fracturing activity. For example, one of the costs associated with fracking is purchasing land and mineral rights. The price of the land on a shale play is a function of urbanization and pre-existing longer run trends in economic activity in that area which may be correlated with recidivism. Examples of this include differential long run trends in depopulation or “brain drain,” where economically disadvantaged areas becoming increasingly disadvantaged over time, meaning that people released into places with more favorable economic conditions also committed their initial crimes in fundamentally different economic situations than those released into poor and declining economies. Ignoring these factors in the estimation of Equation (1) will yield a biased coefficient estimate of the effect of economic output per capita on recidivism, and that bias is, a-priori, difficult to sign, based on the myriad reasons for social and economic differences across places.

To address these potentially confounding effects, we follow Feyrer et al. (2017) and estimate an instrumental variable (IV) model by exploiting arguably exogenous variation in productivity in geographical formations. Specifically, we estimate the following equation

where \(\delta _{st}\) represents shale play-by-year fixed effects and \(\nu _{ct}\) is an error term.Footnote 14 The log specification enables each county to benefit from the shale play productivity in proportion to its relative area within the play. We then follow the basic set up in Feyrer et al. (2017) in our main specification: predicted values from this equation are transformed into level form and scaled by county population, i.e., (\(e^{ \hat{\eta }_{c}+\hat{\delta }_{st}}-1)/Population\). The predicted county level values are then aggregated to commuting zone level in order to create a value of fracking production per capita at the commuting zone level. We use lagged values of these aggregate predictions as instrument for \(New~Value_{zt-1}\) in equation (1).Footnote 15

Note that predictions from equation (2) incorporate timing of new production from shale-plays and abstracts away from idiosyncratic shocks to level of production in the county. Predicted values for new production in the county are based on the timing of new production for all counties in a given shale play, rather than the actual roll out of fracking within any specific county, and thus more credibly exogenous to local economic conditions and criminal behavior of people leaving prison. As discussed in Section 5.3, the results are similar when we use the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation of \(New~Value_{ct}\) in equation (2). Finally, standard errors reported throughout the paper are all clustered at the county level. The precision of the results remains qualitatively unchanged if we instead cluster at the commuting zone or state level.

As a first step, we test for potential post-fracking changes in the composition of released offenders by replacing the dependent variable in equation (1) with several release cohort characteristics. We estimate series of IV regressions where we only control for county and cohort fixed effects (Appendix Table 8). Overall, we do not find any evidence for endogenous changes in neither institutional nor demographic composition of the released offenders.Footnote 16

Results

Baseline Results

We present our baseline results in Table 3. Column 1 reports the estimated effect from an OLS regression while the rest of the columns report the point estimates from IV regressions. In addition, as there is growing evidence pertaining to age-specific nature of labor demand shocks associated with hydraulic fracturing boom (Bartik et al. 2019 and Cascio and Narayan 2022), we also estimate the effects by offender’s age at the time of release (Columns 3 and 4), where we divide cohorts by the median age in our sample (35). Appendix Table 9 reports the results from first-stage and reduced form regressions. The coefficient estimates on the instrument are statistically significant at the 1% level across all first-stage regressions.

The naive impact from the first column of Table 3 is small in magnitude and is not statistically different from zero. When we take into account the potential endogeneity of per capita production by exploiting the variation in resource availability, we obtain an entirely different result. The estimated effect of oil and gas production is negative and significant at the 10% level. The difference between the OLS and IV results suggest that increased economic activity due to more aggressive extraction is associated with higher rates of recidivism, but that association is not causal. This would be the case if, for example, more economically depressed areas had higher rates of recidivism and also more landowners and localities being willing to sell their mineral rights to energy companies at lower prices. The first stage \(F-statistics\), reported in the bottom of Table 3, is 12.22, which is greater than 10–the threshold suggested by Stock and Yogo (2005) for weak instruments; weak instruments will bias the results toward OLS, which in our case is a downward bias.

Consistent with the age patterns of labor demand identified in Bartik et al. (2019) and Cascio and Narayan (2022), we find a larger effect for younger offenders (age 34 and less), shown in Column 3 of Table 3. Specifically, a ten thousand dollars increase in new value per capita from oil and gas production at the commuting zone level decreases the number of younger released inmates returning to prison within 1 year by 4.1%.Footnote 17 Turning to older workers (age 35 and more), we again find a negative effect (2.6% fewer people recidivating per ten thousand dollars of new revenue), but it is smaller in magnitude and is not statistically different from zero. We fail to reject the null hypothesis that the estimated effects from Columns 3 and 4 of Table 3 are equal (\(p-value\)= 0.58).

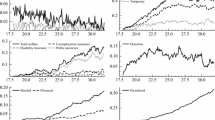

Panel A of Fig. 3 further presents the results of a series of regressions, where we start with a cohort of only the youngest offenders (under the age of 25), and then sequentially add older released offenders to the group up to 40. The relationship between fracking revenue and returns to prison is roughly stable across ages for relatively younger offenders. We also examine return to prison by replacing the dependent variable in equation (1) with log recidivism rate per 100 released inmates (inmates returning to prison divided by release cohort size). The findings from this exercise are consistent with those obtained using recidivism levels, which control for release cohort size in the specifications, although the point estimates are less precise (Panel B of Fig. 3).

The effects of hydraulic fracturing on recidivism-by age. NOTES: The dependent variable in Panel A is natural log of the number of former inmates returning to prison within a year from each release cohort, while it is the log of recidivism rate per 100 released inmates in Panel B. Each point in the panels comes from a separate regression, using samples that increase in age moving rightward along the x-axis. The height of the bars extending from each point represents the bounds of the 95% confidence interval

The NCRP data allow us to track all returns to custody over time, as long as re-offending takes place within the same state. Any systematic outflow of post-release offenders with different propensities to recidivate may conflate changes in recidivism with sample attrition.Footnote 18 The fact that we do not find any meaningful relationship between fracking activity and offender demographics and other related characteristics provides some evidence against such selective migration (Appendix Table 8). To further probe this concern, we re-estimate the effects of oil and gas production by limiting our attention to conditional releases (e.g., parole and probation). People on conditional release are largely geographically constrained, and among this sub-sample we find essentially the same results as in the full sample; a ten thousand dollars increase in new value per capita production at the commuting zone level decreases the number of younger conditionally released inmates returning to prison within 1 year by 3.3%. This suggests that selective migration of former inmates is unlikely to be driving our results.

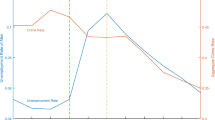

Finally, we examine how recidivism changes over longer time horizons.Footnote 19 First year recidivism, which we measure as return to state prison, may occur because of parole violations or new offenses. To the extent that parole conditions could include employment, economic booms may help former offenders avoid incarceration by both reducing criminal incentives and making it easier to comply with their terms of parole. Our estimates of how economic booms affect 1 year, 2 year, and 3 year recidivism of older and younger offenders, are presented in Fig. 4. We find that the initial short term reductions in recidivism from our primary specification appear to persist for at least three years after release.

The effects of hydraulic fracturing on timing of recidivism. NOTES: The figure plots coefficient estimates from regressions that use timing of recidivism as the dependent variable. In order to observe returns to prison over time without censoring, the effective sample is limited to 2012 and earlier releases. Confidence intervals (95%) are based on standard errors clustered at the county level

To put these numbers into perspective, we use observed production to generate a predicted change in recidivism by county and year and aggregate to the nation level.Footnote 20 Our estimates imply that, by 2014, a total of 2,245 fewer offenders returned to prison during the first year of their release than would have in a world without fracking. We can bound the direct fiscal savings associated with this reduction in spending using Donohue’s (2009) average cost estimate of spending per prisoner per year of $35,000, and Owens’ (2009) marginal cost estimate of $14,000 per prisoner per year. The average cost estimate includes both relevant variable costs, such as those incurred on intake, and irrelevant fixed costs such as building maintenance and correctional employee wages, both of which are excluded from the estimated marginal costs. The average prison sentence of recidivating inmates is 2 years, implying a reduction in prison expenditure of between $63 and $157 million.

Who Benefits from Increased Economic Activity?

Our economic boom is driven by growth in the oil and natural gas industry. As such, it is not obvious that all people released from prison are equally likely to benefit, as all may not be equally able to obtain a position in this industry. Indeed, a county level analysis of the impact on average wages by county and industry (shown in Appendix Table 10) suggest that a $1 increase in fracking revenue increases average wages by $0.15, wages in construction by roughly $0.20 (more than the effect on overall wages), mining and transportation by $0.14 (roughly equal to the overall wage effect), manufacturing by an imprecise $0.02, and other service industries by an imprecise $0.05 (both of which are less than the effect on overall wages). While the economic multiplier associated with fracking may be smaller than some other types of regional shocks, based on existing research the average wage multiplier associated with fracking is likely to be around 1.7, implying a potential reduction in recidivism across people with a broad range of skill sets (Munasib and Rickman 2015). At the same time, this boom did not address any disparities in access that different people may have to employment, either through direct discrimination on the part of employers or more structural differences in the ability of workers to take up available job opportunities, like differences in education attainment or social networks across people in different identity groups.

With these varied wage effect in mind, we extend our analysis in Table 4 to see whether there are differential effects of oil and gas production on recidivism across gender, race, and by the most serious type of original offense. We also show the first stage F-statistics, and generally find that our instrument is reasonably, but not universally, strong within these subgroups.Footnote 21 As shown in the first two columns, we do not observe any appreciable differences in the estimated effects for male and female prisoners. This suggests that even if jobs in fracking tend to be filled by men, the beneficiaries of the increased overall economic development are not so obviously gendered. A negative and non-negligible estimated impact of new value on female recidivism is consistent with the broader economic impacts of this industry-specific boom on labor market opportunities.Footnote 22

We find the estimated effects of new oil and gas production per capita to be more pronounced for white offenders. Although we fail to reject the test of equality of the coefficient estimates in Columns (3) and (4), difference in the point estimates for white and black ex-offenders is non-trivial. There are multiple mechanisms that could cause this disparity in who benefits from economic activity. For example, the fracking boom was not associated with any particular sort of policy change or investment aimed at reducing racial bias in hiring decisions, which may disadvantage Black people with criminal records in a disproportionate way (Agan and Starr 2018). The observation that improvements in the economy may disproportionately benefit white offenders is an important consideration for policy makers, as it suggests additional support may be required for members of historically disadvantaged groups in both economic expansions and economic contractions. However, it also may be the case that the concentration of fracking in rural places where the majority of the population is white may limit our ability to statistically detect an impact on recidivism for Black people.

Next, we examine the relationship between fracking activity and recidivism based on the most serious types of offense associated with an offender’s original incarceration spell. As shown in Columns 5–7 of Table 4, the estimated impact is large for drug and property offenders, while it is small and insignificant for violent criminals. Variation in the substantive size of the impact of economic activity on the recidivism of people convicted of different offenses could have multiple interpretations. It may be that people with violent criminal histories are unlikely to be the marginal worker who might be hired during economic expansions. Alternately, to the extent that people are “specialists” in particular crime types, the relative return to property or drug offenses might be more sensitive to economic conditions than violence.Footnote 23 Consistent with this premise, we find more pronounced effects for offenders who were originally incarcerated for financially motivated crimes such as property crime and selling drugs (Columns 8 and 9). Finally, we test for heterogeneity in recidivism via different types of offenses (Appendix Table 11). Similar to those results presented in Table 4, we find large and more precise coefficient estimates when the outcome is defined as re-incarceration for financially motivated crimes.Footnote 24

Robustness Checks and Additional Estimations

We undertake several additional sensitivity checks to examine the robustness of our results to modeling choices. These results are reported in Table 5. First, we run a log-log model by taking the logarithm of new value per capita from the value of oil and gas production (Panel A). Second, we replace the lagged value in equation (1) with its current value and estimate a contemporaneous model (Panel B). Our results from these two alternative specifications are comparable to those reported in Table 3. We also extend our analysis by including the current and lagged values of new value per capita of the oil and natural gas production at the same time. The contemporaneous effects from these specifications are highly insignificant and are always very close to zero in magnitude. A delayed response may indicate that ex-offenders are more responsive to realized economic gains, which contrasts with Galbiati et al. (2021), which found that offenders are more responsive to information about potential openings than actual opportunities. Of course, we do not observe media coverage of the returns to fracking, and we are also studying a very different context (France vs. the U.S.). Either or both of these factors may explain the difference in our results and those of Galbiati et al. (2021).

Third, we replace the lagged value in equation (1) with its lead version and run a falsification test. In the absence of confounders, new value per capita production at time \(t+1\) should not influence recidivism rates at time t. Reassuringly, as shown in Panel C, the point estimates from this exercise are all virtually indistinguishable from zero.

Fourth, we define our variable of interest at the county level instead of a commuting zone. Doing so mutes the estimated effects of oil and gas production on recidivism, but the impact for younger offenders still continues to be statistically significant (Panel D). The estimated effects from Panel D also highlights the importance of geographic dispersion. Ignoring spatial propagation of fracking activity leads to underestimation of the effects of oil and gas production on recidivism. Fifth, regression estimates weighted by county population are reported in Panel E. Our findings remain unchanged across all of these specifications. Sixth, in Panel F, we cluster the standard errors at the state level and doing so does not affect the statistical inference. Seventh, Appendix Table 12 reports the impact of hydraulic fracturing on recidivism by excluding county and release cohort characteristics. Reassuringly, the IV estimates from Table A6 are similar to those presented throughout the text and alleviates concerns on the potential contamination of the estimated effects due to endogenous controls.

We also estimate the IV models using individual-level offender data. The point estimates from this exercise are consistent with those reported in the text, although imprecisely estimated. For example, a ten thousand dollars increase in new value per capita production at the commuting zone level decreases the likelihood of reoffending by 0.37 percentage points for younger released inmates. Taking the average recidivism rate among counties with no fracking activity as our benchmark, the estimated impact implies a reduction in recidivism of around 3%.

Finally, Appendix Table 13 shows that the causal effects of new value per capita oil and gas production do not change appreciably if we use the inverse hyperbolic sine transformation of both the dependent variable and the instrument (i.e., predicted values in equation [2] without the use of \(+1\)), if we control for lagged values of county crime levels (i.e., total number of arrests), and if we condition on the lagged dependent variable.Footnote 25

Why does Economic Growth Affect Recidivism?

Results from previous sections suggest that the increase in value of hydraulic fracturing activity significantly decreased recidivism. While we are unable to identify exactly what about this industry-specific boom affected recidivism, existing research on the social impacts of fracking points to multiple potential channels. As discussed, there is a sizeable impact of the value of oil and gas production on wages and non-labor income (i.e., royalty payments on land use), as well as on job opportunities. More boradly, these impacts would tend to reduce recidivism driven by economic strain. On the other hand, there are mechanisms through which the increased return to oil and gas production might increase recidivism. There are substantial concerns about negative social impacts from fracking, including air pollution, higher dropout rates, and increased interpersonal conflict stemming from a growing, negatively selected, population (Feyrer et al. 2017; Kearney and Wilson 2018; Bartik et al. 2019; Cascio and Narayan 2022). To further explore mechanisms, we consider the following domains that existing research suggests are associated with criminal activity as alternate outcome variables: (i) wages, (ii) migration inflow, and (iii) air pollution (Raphael and Winter-Ebmer 2001; Bell et al. 2012; Spenkuch 2014; Herrnstadt et al. 2016).Footnote 26

Columns (1–3) of Table 6 report the estimated effects of new value per capita from oil and gas production on various county-level outcomes. We find a large and significant impact of oil and gas production on migration inflow. Specifically, a ten thousand dollars increase in per capita production increases in-migration by around 5% (Column 1). We also find a negative and significant impact of oil and gas production on the number of unhealthy days.Footnote 27 Although a negative relationship between county air pollution and drilling may look surprising, there is growing evidence regarding the mitigating role of fracturing on air pollution through reductions in emissions of carbon monoxide, particulate matter and nitrogen oxides. This may follow from the growth in shale gas production which substantially reduced energy prices and in turn may led to a substitution away from coal towards gas in power generation (Jackson et al. 2014; Moore et al. 2014).Footnote 28 Finally, as shown in Appendix Table 10 and reproduced here in Column 3 of Table 6, every $1 of new production at the community zone level generates a wage increase of $0.15.

Panel B of Table 6 reports the association of these variables with recidivism from panel regressions which control for county and release cohort fixed effects and all other covariates.Footnote 29 Migration inflow and wages are negatively correlated with recidivism. These associations are statistically significant (Columns 4 and 6) and are consistent with the existing studies.Footnote 30 Migration inflow is likely to increase local public safety expenditures such as the total number of police officers (Street 2019). To the extent that released offenders are able to observe the increase in these expenditures and perceive a higher risk of apprehension, reoffending is expected to decline through the deterrence channel (Becker 1968). Column 5 of Table 6 suggests a positive and less precisely estimated correlation between air pollution and recidivism.

To determine the predictive power of each channel, we multiply the point estimates from Columns (4)-(6) with their corresponding counterparts in Columns (1)-(3). The validity of this exercise hinges on the unbiasedness of the estimated effects from Columns (4)-(6). This is a very generous assumption, but, with this proviso in mind, multiplying the coefficient estimates from the first and fourth columns yield a value of \(-\)0.012, meaning that increased migration inflow can predict around 40% of the observed effect in Column 2 of Table 3. Applying the same translation to wages (Columns 3 and 6) suggests a similar predictive power (40%).Footnote 31

To shed further light on the underlying mechanisms, we analyze the heterogeneity in the effects of oil and gas production across different time periods. Feyrer et al. (2017) show that the economic benefits of hydraulic fracturing activity are significantly more pronounced in the early years of fracking boom (2005–2008) and during the Great Recession (2009–2011). To the extent that reduction in recidivism works through economic responses to local shocks, one would expect to see larger effects in these two respective time periods. Reassuringly, we find that a ten thousand dollar increase in new value per capita production at the commuting zone level decreases recidivism rates both in the early years and during the recession, while the effects for the 2012–2014 period are almost equal to zero in magnitude across all columns (Appendix Table 14). The Sanderson-Windmeijer \(F-statistics\) are reported in the bottom of the table, indicating that weak instruments are not an issue.Footnote 32

Revisiting the Fracking-Crime Relationship

Observed patterns in the NCRP suggest that, when it comes to a specific type of criminal behavior, hydraulic fracturing has had a protective effect on certain communities. Ex-offenders who are released to places where shale plays were more productive are less likely to be re-incarcerated after 1 year. This stands in contrast with existing research which finds that fracking is associated with increased criminality (James and Smith 2017; Bartik et al. 2019),Footnote 33 but is consistent with studies focused on criminal behavior of people who lived in these particular places prior to fracking (Street 2019).

In order to better understand the apparent conflict between our results and some of the existing crime literature, we first replicate the existing finding that fracking increases crime within our sample. Specifically, we replace the outcome of interest (recidivism) from equation (1) with the natural log of the total number of reported crimes and arrests, obtained from the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports (UCR).Footnote 34 The findings from this exercise are consistent with James and Smith (2017) and Bartik et al. 2019 that use the same data to examine the impact of fracking on crime (Appendix Table 15). We estimate a positive, but insignificant, relationship between economic activity and reported crime, and a 5.5% increase in the number of arrests after a ten thousand dollar increase in per capita production, indicating that the positive relationship between fracking and overall crime is robust to any arbitrary differences in sampling and modeling choices across papers.Footnote 35

Taken at face value, these results suggest that the impact of fracking on crime may be a heterogeneous function of the identity of the potential offender. We are able to show that fracking results in a large in-migration of young men to affected counties. The simultaneous increase in crime and reduction in recidivism is consistent with these new immigrants having higher propensities to engage in crime. In contrast, the increased economic benefits for ex-offenders, who for the most part were living in the area prior to the fracking boom and thus have some pre-existing ties to the community or “social capital,” reduces their propensity to offend. Further research that exploits credibly exogenous variation in both community ties and economic opportunity is needed to rigorously test this hypothesis.

Conclusion

In this paper, we examine how economic growth affects recidivism. We focus on variation in economic activity generated by the natural gas and oil industry during the fracking boom. In contrast to existing research which found that fracking was associated with an increase in crime rates, and consistent with the existing literature on labor market demand and crime, we find evidence that increased production, measured in value of energy production, is associated with lower recidivism rates. Our findings add nuance to the finding that economic activity, and fracking in particular, can lead to higher crime rates, and suggests that much of the social costs of frac king may be driven by selective in-migration.

By exploiting the variation in the location of shale plays and the timing of fracking initiation in an instrumental variables framework, we find that a ten thousand dollar increase in the value of per capita energy production is associated with a 2.8% reduction in the 1 year recidivism rate of ex-offenders at the county level. This is qualitatively identical to current estimates of the change in recidivism associated with a one standard deviation increase in construction jobs (Schnepel 2018), or typical employment growth over the course of a business cycle (Yang 2017), but slightly smaller than typical wage growth during a business cycle (Yang 2017). Our estimates suggest that the increased economic activity generated by fracking resulted in almost 2,250 fewer offenders returning to prison (within 1 year of release) between 2006 and 2014. While there are multiple mechanisms linking economic activity to recidivism, increased wages appear to explain a non-negligible fraction of the reduction in recidivism. Several robustness checks and falsification tests support our results.

In a broader sense, our findings suggest that studies that use aggregate crime data to evaluate the impact of local economic development programs will mask important individual level heterogeneity in the response to those programs. While predicting the exact source of this heterogeneity is outside the scope of this paper, it is possible that social ties condition the relationship between income shocks and crime. Further research on why, and when, economic growth reduces criminal behavior is necessary.

Notes

See Cochran (2019) for a recent review of this research.

There are more than 20 shale plays and 10 shale basins in the U.S. The top ten shale plays generate the majority of oil and natural gas production in the U.S. Note also that a basin may contain more than one shale play. See Figures 1 and 2 for the distribution of shale plays and basins in the contiguous U.S.

Delaware and New Mexico did not reveal county information and thus are dropped from the analysis sample.

The findings from the criminal mobility literature indicates that more than 90% of all offenders reside in county of conviction post-release (Raphael and Weiman 2007). Perhaps not surprisingly, consistent with this general consensus, around only 9% of all observed recidivism activity in the NCRP data occurs in a different location than the county in which first offense was observed. Finally, as discussed below, our main identification strategy exploits variation at the commuting zone level which is likely to alleviate any concerns related to spatial propagation.

We opt out of using the county from second conviction as a proxy for each offender’s post-release location because subsequent location can potentially be endogenous to fracking activity. Nevertheless, we experiment with our analysis by excluding offenders whose county of second conviction is different than that of the first one. Doing so does not alter any of our findings. These results are available upon request.

DrillingInfo is an oil and gas exploration and production and analytics company based in Austin, Texas. The details about how the total new value of oil and natural gas extraction (from new wells) is constructed is available in Feyrer et al. (2017).

As noted, NCRP began in 2000 with the participation of 15 states, meaning information on recidivism rates date back to early 2000 s for several states.

Individual county production, on average, comprises 3% of the total annual production at the shale play level.

The states that did not participate in NCRP between 2005 and 2014 are obviously omitted from this figure.

These shales plays (basins) are Bakken (Williston), Barnett (Fort-Worth), Eagle Ford (Western Gulf), Fayetteville (Arkoma), Haynesville (TX-LA- MS Salt), Marcellus (Appalachian), Niobrara-Denver (Denver), Niobrara-Greater Green River (Greater Green River), Niobrara- Powder River (Powder River), Permian All Plays (Permian), Utica (Appalachian), Woodford-Anadarko (Anadarko), Woodford- Ardmore (Ardmore) and Woodford-Arkoma (Arkoma).

The NCRP data are not available for Arkansas during our analysis period and therefore, Fayetteville is excluded in the analysis below.

The full set of controls include the proportion of the county population who are female, white, black and Hispanic, proportion of the county population with high school degree or less, county population, release cohort size, proportion of release cohort that are male, white, black and Hispanic, average age of offenders at the time of release, proportion of release cohort with a high school degree or less, proportion of release cohort convicted of a felony crime, violent, property and drug-related crimes. We will later return to this point and show that excluding these controls does not have a large impact on the estimated effects of fracking on recidivism (Appendix Table 12).

We allocate counties to commuting zones using the crosswalk files of David Dorn. The 1990 crosswalk files are available at http://www.ddorn.net/data.htm.

Each county in the effective sample is assigned to a shale play. There are more than 20 designations of plays.

More precisely, the first stage equation is given as

$$\begin{aligned} New~Value_{zt-1}=\pi _{0}+\pi _{1}New~Value\_Inst_{zt-1}+X_{ct}^{\prime }\pi _{2}+\eta _{c}+\lambda _{t}+\eta _{zt} \end{aligned}$$where \(New~Value\_Inst_{zt-1}\) is obtained using the predicted values from equation (2).

We also investigate the correlations between our instrument and pre-fracking county covariates (e.g., unemployment rate, income and proportion of the county population with high school degree or less) in 2000. We generally cannot reject the hypothesis that the covariates are not associated with average value of aggregate predictions per capita between 2006 and 2014.

Note that a ten thousand dollars increase is slightly less than one standard deviation of new value from Table 2.

Recall that any potential contamination in the estimated effects stemming from selective migration within the state is picked up by our instrumental variable approach.

In order to observe 3-year recidivism without any censoring, we limit our effective sample to 2012 and earlier releases.

We first obtain the point estimate from an IV regression (controlling for all other covariates) of total number of inmates returning to prison within a year on new oil and gas production per capita. We multiply the point estimate from this regression with observed production by county and year. Predicted changes in recidivism are then annually aggregated to nation level and summed over time.

The sample sizes across columns vary because counties do not have offenders in all subgroups for all years. This also explains the lower first stage \(F-statistics\) values for a few subgroups.

Our conclusions remain intact when we further explore the heterogeneity by gender and age groups. Specifically, all point estimates are negative and we again fail to reject the test of equality among all four subgroups.

The extent to which people specialize in drug, property, or violent offenses is a source of active empirical and theoretical work in criminology, and likely varies by the age of a particular offender. See Thomas et al. (2020) for recent work in this area.

Among inmates who were conditionally released, a ten thousand dollar increase in new value per capita production is associated with a 3.1% reduction in the 1 year recidivism rate when the outcome is defined as re-incarceration for new commitments. The analogous effect for technical violations is not statistically different from zero and the point estimate is 0.010 (s.e.=0.007).

Replacing the control for crime levels with that of crime rates does not change the results in a meaningful way. It is well known that fixed effects models with lagged dependent variables are biased when the number of time periods for which data are available is small. Our goal in conditioning on lagged dependent variable is to show that the coefficient estimates on new value remain unchanged.

By exploiting variation in pollution driven by daily changes in wind direction, Herrnstadt et al. (2016) show that short-run changes in ambient pollution has a positive impact on the likelihood of committing a violent crime. Bell et al. (2012) examine the effect of increases in asylum-seekers on crime for England and Wales and find a higher incidence of property crime induced by asylum-seekers who face substantial barriers to labor market participation. Exploiting immigrants’ tendencies to settle in ethnic clusters and using county level data, Spenkuch (2014) finds a significant and increasing effect of immigrant stocks on property crime rates but no impact on violent crime. Of course, there is a growing literature finding that the impact of immigration on crime is context dependent, particularly when it comes to economic opportunities (Fasani 2018).

Note that, in Column 2, we lose a large number of observations because Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) pollution monitoring network is not available for all counties. This type of data limitation may lead to a selected sample which may result in different coefficient estimates than in our primary specification in Table 3. The effect of new value per capita from oil and gas production on recidivism is statistically significant and is slightly above 7% when we limit our analysis to the sample from Column 2 of Table 6. This estimated impact is almost three times of that reported in Column 2 of Table 3 and therefore, caution is warranted in interpreting the point estimates from pollution analysis. To further examine potential selection bias, we create an indicator variable that takes the value of one if annual county level pollution data is missing. The point estimates from cross sectional analysis are generally significant.

Number of unhealthy days in any given year refers to total number of days when air quality index (AQI) value ranges between 151 to 200. The defining parameters of AQI are Criteria Gases and Particulates. The results remain the same when we use other measures of air pollution such as maximum AQI or the 90th percentile AQI.

Natural gas prices fell by two-thirds from around $10 per million thermal units to $3 over the last decade (U.S. Energy Information Administration 2016b).

Measures of mechanism are aggregated to commuting zone level in Columns (4)-(6) to be consistent with the rest of the paper.

Yang (2017) finds that a 5% increase in real wages decreases the probability of re-offending by 2.3%. Similarly, Agan and Makowsky 2021 shows that a $0.50 increase in average minimum wages (8% increase relative to sample mean) reduces the likelihood of returning to prison within 1 year by 2.8%. The estimated association reported herein is consistent with these estimates. Specifically, a ten thousand dollar increase in wages per capita (approximately 25% increase relative to sample mean) is associated with a 8.1% decrease in the 1 year recidivism rate. A 5% increase in wages per capita is then roughly equal to 1.6% decrease in the 1 year recidivism rate.

We analyze other important pathways that may help explain the relationship between oil and gas production and recidivism. For example, we consider the impact of fracking activity on log of total number of police officers at the county level. The point estimate from this regression is 0.017 (s.e.=0.007) and increased policing can predict around 7% of the observed effect in Column 2 of Table 3.

Note that we have three instruments (lagged predicted new value per capita production and its interactions with time period dummies).

It is possible that recidivism could fall because of “law enforcement swamping,” where local law enforcement becomes so overwhelmed by crime that recidivism is less likely to be detected. While we technically cannot rule out unrecorded criminal activity, we believe this channel is highly unlikely to be driving our results. People with criminal histories are both formally, and as a matter of practice, under higher levels of supervision than the general public. Re-offending in almost all jurisdictions is explicitly considered more serious than first time offending, in terms of increased sentence length and probability of conviction. Both factors make it unlikely that people recently released from prison would be the marginal criminal no longer subject to police scrutiny.

We use the county-level UCR crime data, and aggregate agency level arrests data by county, both provided by Jacob Kaplan via openICPSR. Our use of the county-level UCR crime data requires assuming that the known measurement error in this data set is uncorrelated with our measure of economic activity, a caveat shared by existing county-level studies of fracking and crime. That said, given that the positive relationship between crime and fracking has been observed at multiple levels of spatial aggregation, we think this assumption is reasonable. We exclude all duplicate observations in the annual arrest data, and sum all arrests by the FIPS information added to the data by Dr. Kaplan.

We also investigate the relationship between fracking activity and crime by replacing total number of reported crimes and arrests with corresponding measures of crime rates, which are defined as log of total number of reported crimes and arrests per 10,000 adult population in the county. The estimated effects for log of reported crime and arrest rates are 0.020 (s.e.=0.016) and 0.066 (s.e.=0.030), respectively.

References

Agan A, Starr S (2018) Ban the box, criminal records, and racial discrimination: a field experiment. Quart J Econ 133(1):191–235

Agan AY, Makowsky MD (2021) The minimum wage, EITC, and criminal recidivism. J Human Resour

Alper M, Markman J(2018) 2018 update on prisoner recidivism: a 9-year follow-up period (2005–2014). Bureau of Justice Statistics

Bartik AW, Currie J, Greenstone M, Knittel CR (2019) The local economic and welfare consequences of hydraulic fracturing. Am Econ J Appl Econ 11(4):105–155

Becker GS (1968) Crime and punishment: an economic approach. J Polit Econ 76(2):169–217

Bell B, Fasani F, Machin S (2012) Crime and immigration: evidence from large immigrant waves. Rev Econ Stat 95(4):1278–1290

Bushway S, Reuter P (2001) Labor markets and crime. In: Crime, eds. Wilson J, Petersilia J,pp 191–224

Cascio EU, Narayan A (2022) Who needs a fracking education? The educational response to low-skill-biased technological change. ILR Rev 75(1):56–89

Cochran, J. C. (2019). Inmate social ties, recidivism, and continuing questions about prison visitation BT—e Palgrave handbook of Prison and the Family. pp. 41–64. Cham: Springer International Publishing

Corman H, Mocan N (2005) Carrots, sticks, and broken windows. J Law Econ 48(1):235–266

Denver M, Siwach G, Bushway SD (2017) A new look at the employment and recidivism relationship through the lens of a criminal background check. Criminology 55(1):174–204

Doleac, J. (2020). A review of Thomas Sowell’ys discrimination and disparities. Working paper

Donohue JJ (2009) Assessing the relative benefits of incarceration: overall changes and the benefits on the margin. In: Raphael S, Stoll MA (eds) Do prisons make us safer? The benefits and costs of the prison boom. Russell Sage Foundation, New York, pp 269–342

Fasani F (2018) Immigrant crime and legal status: evidence from repeated amnesty programs. J Econ Geograph 18(4):887–914

Feyrer J, Mansur ET, Sacerdote B (2017) Geographic dispersion of economic shocks: evidence from the fracking revolution. Am Econ Rev 107(4):1313–1334

Galbiati R, Ouss A, Philippe A (2021) Jobs, news and reoffending after incarceration. Econ J 131(633):247–270

Herrnstadt, E., A. Heyes, E. Muehlegger, and S. Saberian (2016). Air pollution as a cause of violent crime : evidence from Los Angeles and Chicago. Working Paper

Jackson RB, Vengosh A, Carey JW, Davies RJ, Darrah TH, O’Sullivan F, Pétron G (2014) The environmental costs and benefits of fracking. Annu Rev Environ Resour 39(1):327–362

James A, Smith B (2017) There will be blood: crime rates in shale-rich U.S. Counties. J Environ Econ Manag 84:125–152

Kearney MS, Wilson R (2018) Male earnings, marriageable men, and nonmarital fertility: evidence from the fracking boom. Rev Econ Stat 100(4):678–690

Laub JH, Sampson RJ (2001) Understanding desistance from crime. Crime Justice 28:1–69

Moore CW, Zielinska B, Pétron G, Jackson RB (2014) Air impacts of increased natural gas acquisition, processing, and use: a critical review. Environ Sci Technol 48(15):8349–8359

Munasib A, Rickman DS (2015) Regional economic impacts of the shale gas and tight oil boom: a synthetic control analysis. Reg Sci Urban Econ 50:1–17

Nagin DS (2013) Deterrence in the twenty-first century. Crime Justice 42:199–263

Nagin DS, Cullen FT, Jonson CL (2009) Imprisonment and reoffending. Crime Justice 38(1):115–200

National Academies of Sciences Engineering and Medicine (2018) Proactive policing: effects on crime and communities. The National Academies Press, Washington, DC

Owens EG (2009) More time, less crime? Estimating the incapacitative effect of sentence enhancements. J Law Econ 52(3):551–579

Pager D (2011) Comment: young disadvantaged men: reactions from the perspective of race. Ann Am Acad Polit Soc Sci 635(1):123–130

Raphael S (2011) Improving employment prospects for former prison inmates: challenges and policy. In: Cook PJ, Ludwig J, McCrary J (eds) Controlling crime: strategies and tradeoffs. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Raphael S, Weiman DF (2007) Returned to Custody. In: Bushway S, Stoll M, Weiman D (eds) Barriers to reentry?: The labor market for released prisoners in PostIndustrial America, Chapter 10. Russell Sage Foundation

Raphael S, Winter-Ebmer R (2001) Identifying the effect of unemployment on crime. J Law Econ 44(1):259–283

Schnepel KT (2018) Good Jobs and Recidivism. Econ J 128(608):447–469

Spenkuch JL (2014) Understanding the impact of immigration on crime. Am Law Econ Rev 16(1):177–219

Stock JH, Yogo M (2005) Testing for weak instruments in linear IV regression. In: Andrews DWK, Stock JH (eds) Identification and inference for econometric models: essays in honor of Thomas Rothenberg. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, pp 80–108

Street, B. (2019). The impact of economic opportunity on criminal behavior: evidence from the fracking boom. Working Paper

Stretesky P, Grimmer P (2020) Shale gas development and crime: a review of the literature. Extr Indus Soc 7(3):1147–1157

Thomas KJ, Loughran TA, Hamilton BC (2020) Perceived arrest risk, psychic rewards, and offense specialization: a partial test of rational choice theory. Criminology 58(3):485–509

U.S. Energy Administration Information. Drilling Productivity Report (various years)

U.S. Energy Administration Information. Hydraulic Fracturing Accounts for about Half of Current U.S. Crude Oil Production. https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=25372

Yang CS (2017) Local labor markets and criminal recidivism. J Public Econ 147:16–29

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

We would like to thank John MacDonald and three anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions. All results, conclusions and errors are our own.

Appendix A

Appendix A

See Tables 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eren, O., Owens, E. Economic Booms and Recidivism. J Quant Criminol 40, 343–372 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-023-09571-2

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-023-09571-2