Abstract

Objectives

This study estimates the causal effect of paternal incarceration on children’s educational outcomes measured at the end of compulsory schooling (9th grade) in Denmark.

Methods

I use Danish administrative data and rely on a sentencing reform in 2000, which expanded the use of non-custodial alternatives to incarceration for traffic offenders, for plausibly exogenous variation in the risk of experiencing paternal incarceration.

Results

The results show that paternal incarceration does not affect academic achievement (grade point average), but that it does reduce the number of grades obtained, and–most importantly–roughly doubles the risk of not even completing compulsory school and getting a 9th grade certificate. These findings are driven mainly by boys for whom paternal incarceration appear to be particularly consequential.

Conclusions

The findings presented in this study highlight the presence of unintended and collateral consequences of penal policies–even in the context of a relatively mild penal regime. Effects are, however, estimated for a subgroup of Danish children experiencing paternal incarceration, and how results translate to other subgroups and beyond the Danish context is open for speculation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Paternal incarceration has been linked to a wide range of detrimental outcomes such as poor health (Roettger and Boardman 2012; Turney 2014; Wildeman et al. 2014), behavioral problems (Geller et al. 2012; Turney 2021; Wildeman 2010) and crime (Besemer et al. 2011; Murray and Farrington 2005; Porter and King 2015; Roettger and Swisher 2011; Wildeman and Andersen, 2017). Coupled with staggeringly high rates of paternal incarceration among disadvantaged children particularly in the United States (Wildeman 2009) this experience has the potential perpetuate and enhance existing inequalities between families and across generations and may do so through various channels and domains.

Schools represent a significant social arena in which children are embedded–second only to the family in importance–and educational outcomes have profound consequences for a wide range of aspects of an individual’s later life and future life chances in general (Lochner and Moretti 2004; Oreopoulos and Salvanes 2011). Thus, a significant number of studies have also examined how incarceration may have consequences for how the next generation fairs within the educational system. These studies generally find paternal incarceration to be associated with poorer educational outcomes on a wide range of measures (e.g., Andersen 2016; Foster and Hagan 2009; Hagan and Foster 2012; Haskins 2016; McCauley 2020; Turney 2017; Turney and Haskins 2014).

However, disentangling causal effects of paternal incarceration from differences in outcomes that are due to differences in pre-existing disadvantaged or other adverse experiences is a tricky endeavor and only few of the previous studies employ research designs that convincingly allow them to circumvent selection on unobservable factors. The studies that most convincingly address the issue of unobserved selection–either by treating the timing of paternal incarceration as plausibly exogenous (McCauley 2020) or by taking advantage of random allocation to judges (Bhuller et al. 2018; Dobbie, Grönqvist, Niknami, Palme, and Priks 2018; Norris, Pecenco, and Weaver 2021)–find no or only limited support for causal effects on grades, high school graduation, and being enrolled in schooling at age 20, thereby casting doubt on the harmful effects of paternal incarceration on educational outcomes. But if those most vulnerable to potential detrimental effects of paternal incarceration only have marginal attachments to the educational system, these outcomes might not capture the margin, where educational effects are expected to be strongest. Given the already poor performance of children with just minimal paternal criminal justice contact (Andersen 2016) it could be beneficial to examine early or minimal level educational outcomes in compulsory schooling, rather than high school, upper secondary or later measures of educational attainment, where children exposed to paternal incarceration may never have had very good outcomes–neither in the absence or presence of paternal incarceration.

In this paper, I rely on Danish administrative data and plausibly exogenous variation in the risk of paternal incarceration arising from a sentencing reform to estimate causal effects of paternal incarceration on educational outcomes measured at the end of compulsory schooling. Compulsory schooling in Denmark consists of integrated primary and lower secondary school and runs until 9th grade, where students are most often aged 15–16. By studying outcomes as early in the education system as possible and measuring both performance (grade point average, GPA), participation (grades obtained) and completion, I make a serious effort to examine effects at the margin where consequences for those with the weakest attachment to the educational system may be more likely to manifest themselves. By including these measures, I am also able to compare findings for outcomes that to a greater or lesser extent reflect academic or cognitive abilities. The sentencing reform in 2000 expanded the use of non-custodial alternatives to prison for traffic offenders, who went from a certain prison sentence before the reform to having three different sentencing options after the reform, that is (1) prison sentence, (2) suspended sentence with community service, and (3) suspended sentence with alcohol treatment. Relying on the plausibly exogenous variation introduced by the sentencing reform enables me to compare children whose fathers were sentenced to prison with children whose fathers were sentenced to non-custodial alternatives to prison, but who would have been sentenced to prison had the reform not been introduced (similar research designs have been used by Wildeman and Andersen (2014, 2017) to identify effects of paternal incarceration on foster care placement and criminal charges).

I find that paternal incarceration negatively affects children’s educational outcomes at the end of compulsory schooling. The negative effects pertain not so much to cognitive or academic abilities–as no causal effect is found on GPA–but rather the chances of putting those abilities to use. I find that paternal incarceration results in a moderate decrease in the number of grades obtained, and substantially increases the risk of not even completing compulsory school, which is a very rare occurrence in the Danish context. Without a diploma from compulsory schooling, future labor market opportunities are severely hampered and the risk of engaging in criminal activities is particularly high among this group making non-completion of this minimal level of education a quite consequential outcome. Additionally, results suggest that effects are mostly driven by the boys, thereby joining several studies pointing to gendered effects of paternal incarceration.

These results point to important and unintended consequences of penal policies and highlight how offenders, although punished as individuals, are often embedded in family networks in which a given punishment can have negative spill-over effects.

Background

With a heavy reliance on incarceration in especially the United States, paternal incarceration has become a common childhood experience among disadvantaged children with 50% of black children of high school drop-outs experiencing paternal imprisonment by age 14 (Wildeman 2009). Unpacking the consequences of this common–and unequally distributed event–has therefore gained the attention of criminologist, sociologists, and economists alike, and paternal incarceration has by now been linked to a wide range of detrimental outcomes both within and outside the United States. Particularly salient in shaping future life chances are educational outcomes, as they influence both future employment, income and health (Oreopoulos and Salvanes 2011) as well as criminal outcomes (Lochner and Moretti 2004). Examining educational consequences of paternal incarceration, thus informs us of the potential wide reach of penal policies–across generations and across institutional domains.

Paternal Incarceration and Children’s Educational Outcomes

Separation, Strain, Stigma, and Selection

Paternal incarceration can impact children’s educational outcomes through (1) the parent–child separation, (2) the strained family environment, and (3) the stigmatization that paternal incarceration may entail. These proposed mechanisms mirror the ones linking paternal incarceration to other outcomes, as they are thought to influence child well-being–a foundation for behavior, learning, and performance in school.

First, incarceration may interrupt and weaken attachment between father and child, which may have adverse developmental consequences (Bowlby 1985; Poehlmann 2005). Specifically, incarceration is thought to damage parent–child attachment both through physical separation (Murray and Farrington 2008), and through fathers diminished ability to engage positively with their children following incarceration (Smith and Jakobsen 2010; Turney and Wildeman 2013; Turney et al. 2012). Missing a parent (during incarceration) or a diminished closeness between parent and child (after incarceration) may result in a child having difficulty concentrating in school or in a child acting out in school.

Second, paternal incarceration may put a strain on the entire family and reduce the family resources available to the child. Families are likely to experience financial hardship due to income loss, which may result in less financial and social support for the child (Murray and Farrington 2008). Incarceration may also strain parents’ relationship and the remaining parent’s mental health, and paternal incarceration have been shown to increase both the risk of family disruption (Turney and Wildeman 2013) and maternal depression and parenting stress (Dennison et al. 2019; Wildeman et al. 2012). Such a strained family environment may negatively impact the level of stress, energy, or general well-being that a child brings to school as well as the time and help for homework received at home, thus impacting both the readiness to learn, academic performance, and behavior in school. However, in cases where the father represents a disruptive or even violent presence in the family, paternal incarceration may also be a relief for children and other family members (Hagan and Dinovitzer 1999; Wildeman 2010).

Third, paternal incarceration may result in children being stigmatized or socially isolated in the school context. The stigma of a criminal record has been shown to affect subsequent employment opportunities (Pager 2003), but children whose parents spend time in prison may also acquire a stigma by association (Goffman 1963) as people attribute negative characteristics to them solely based on their relation to the incarcerated parent. Particularly, teachers have been shown to lower their expectations of children of incarcerated parents (Dallaire et al. 2010; Wildeman, Scardamalia, Walsh, O’Brien, and Brew, 2017) which may impact both grading, learning, performance, and behavior in school and thus very directly affect educational outcomes.

Finally, associations between paternal incarceration and poor educational outcomes, may be spurious and due to selection rather than causal effects of separation, strain or stigma. Poor educational outcomes and paternal incarceration are likely to occur in the same families and could both be symptoms of the same underlying dysfunctional features, but not be causally linked. Factors such as parental criminality, low IQ, poor parenting practices, possibly including negligence, violence and abuse are underlying risk factors that affect children’s life chances and co-occur with or even increase the risk of paternal incarceration (Hagan and Dinovitzer 1999; Olsen 2013; Porter and King 2015). Additionally, many children whose father or mother has been incarcerated have also been exposed to adverse family and neighborhood characteristics such as poverty, parental substance abuse and mental health problems (Cho 2009), all of which can affect the children’s educational outcomes. Separating causal effects from selection, which is a central goal of this study, is essential if we want to know which adversities can be attributed to and addressed by penal policies.

Moderators

If paternal incarceration indeed has a causal effect on children’s educational outcomes it is by no means given that the consequences are equal across experiences and for all children. Some children may be more susceptible to potential adverse effects of paternal incarceration and some experiences of paternal incarceration may be particularly detrimental (Murray and Farrington 2008).

Paternal incarceration can both interfere with a child’s life as an event stressor or as a chronic stressor depending on the experience being unanticipated (and most likely occurring for the first time) or anticipated and feeding into a repeated pattern of cumulative disadvantage (Turney 2017). In cases of repeated or anticipated paternal incarcerations family resources may be particularly depleted leaving little room to shield children from potential harmful effects. However, when no prior paternal incarceration has occurred, the event may be particularly potent as it unexpectedly disrupts families yet to experience the strain, separation and stigma that paternal incarceration may entail. In such cases, the father is more likely to be a substantial source of financial support and families may still be intact, and Turney’s (2017) results do indeed show paternal incarceration to be most detrimental when the experience was unanticipated.

Paternal incarceration could also affect boys and girls differently. The stigma of having a father incarcerated may hit boys particularly hard (Wildeman et al. 2017) potentially due to gendered expectations that boys follow in the footsteps of their fathers. Evidence also suggest that fathers spend more time with and engage more in the parenting of boys than girls (e.g., Lundberg et al. 2007; Yeung et al. 2001), and the separation from a father may therefore come a larger cost for boys than girls. Boys and girls may also cope with adverse events and stressful situations in different ways (Kort-Butler 2009), some of which may be more detrimental to successful educational outcomes than others.

Furthermore, differences in effects across these dimensions–gender and whether the incarceration is a first-time (and potentially unexpected) occurrence–may interact to create unique effects of paternal incarcerations across subgroups. For example, if girls tend to respond to stressful events with avoidant coping patterns (Kort-Butler 2009) they may be able to hide their response to paternal incarceration better than boys, who may tend to respond with more expressive, action-oriented coping styles and “act out” in school as an immediate response to paternal incarceration. For girls, it may thus not be the first-time experience of paternal incarceration that manifests itself in poor educational outcomes, but rather experiences of prolonged situations of instability and repeated paternal incarcerations.

Existing Evidence

There is ample existing evidence linking paternal incarceration to a wide range of educational outcomes, but not all studies employ research designs that allow them to rule out selection from unobservable factors thereby reducing the confidence in the interpretation of the estimates as causal effects of paternal incarceration. One group of studies focus on educational outcomes measured early in school (age 5–9) and include a broad range of cognitive and non-cognitive skills. This group of studies rely on data from the United States (in particularly the Fragile Families and Child Well-being Study) and generally find paternal incarceration to be associated with poorer cognitive and non-cognitive skills along with higher risks of grade retention and special education placement (Haskins 2014, 2016; Turney 2017; Turney and Haskins 2014), although results for cognitive skills are rather mixed when controlling for covariates (Haskins 2014; Turney 2017). Despite including an impressive list of covariates (often using propensity score matching), these studies still lack strong causal design to address selection bias from any unobserved factors.

Another group of studies focus on educational achievements such as years of completed education, high school completion and grades which are generally measured in (young) adulthood. Drawing on data from both the United States and Scandinavia, the studies find that paternal incarceration is associated with lower high school grades, higher risk of high school drop-out and lower levels of completed education (Andersen 2016; Bhuller et al. 2018; Dobbie et al. 2018; Foster and Hagan 2009; Hagan and Foster 2012; McCauley 2020; Olsen 2013) and associations most often persist after controlling for a wide range of observable covariates. Four studies stand out with research designs that lend themselves well to circumventing (unobserved) selection into paternal incarceration. One compares children experiencing paternal incarceration with children who will experience this in the future (thereby limiting sources of unobserved selection bias, although timing of paternal incarceration may still not be randomly distributed) and find some effects on high school grades, but more consistently on behavioral outcomes like fighting, suspension and expulsion (McCauley 2020). Three other studies use random allocation to judges in Ohio as well as Sweden and Norway and do not find support for causal effects on school grades, high school graduation, and being enrolled in schooling at age 20 (Bhuller et al. 2018; Dobbie et al. 2018; Norris et al. 2021). Since the Scandinavian countries share many societal features including a more lenient criminal justice system compared to the United States, these latter two studies are the ones that most readily compares to the current study.

Taken together, the bulk of the research points to negative effects of paternal incarceration on educational outcomes. But the more rigorous studies cast doubt on whether effects carry on into broader measures of educational attainment later in life. However, if those with the weakest attachment to the educational system are most likely to be affected by paternal incarceration then it would be more plausible to see effects in early or minimal level educational outcomes, where there is likely to be more variation in the outcomes of these individuals, rather than in later or more advanced measure of educational achievement and enrolment, where they may never have had very good outcomes–neither in the absence or presence of paternal incarceration.Footnote 1

Furthermore, the existing research also indicates that the distinction between educational outcomes that pertain to cognitive skills (such as reasoning, verbal abilities, academic subject knowledge, and problem solving) and non-cognitive skills (such as effort, discipline, aggressiveness, sociability, and self-esteem) is significant. While, the cognitive skills are closely related to academic abilities and performance, the non-cognitive skills are also of great importance in educational outcomes and later occupational attainment (Farkas 2003). The evidence regarding paternal incarceration and cognitive skills or academic performance is much more mixed than evidence regarding non-cognitive skills and behavior or participation in school. Following this, we should expect to see greater effects on outcomes, where behavior, non-cognitive skills and non-academic processes play a larger part (such as obtaining grades and completing school) relative to outcomes, that are more closely related to cognitive skills and academic abilities (such as grade-point-average).

The current study builds on the previous research by (1) applying a rigorous research design well equipped at ruling out (unobserved) selection and estimating causal effects of paternal incarceration, and (2) including educational outcomes that capture both academic performance (GPA), participation (grades obtained) and completion and thus to a greater or lesser extent reflect academic and cognitive abilities at a margin where there is still likely be some variation in the outcomes of those with the weakest attachment to school.

The Danish Context

When studying paternal incarceration in Denmark, particularly two features of the Danish context are likely to impact the findings and how they fit into the broader knowledge of the consequences of paternal incarceration.

First, Denmark has a mild penal regime with much lower imprisonment rates (63 people imprisoned per 100.000 in the population (World Prison Brief 2018)) compared with the United States and many other European and Western countries. The low imprisonment rate reflects that fewer people are sent to prison, and when they are, prison sentences are usually short (60% of all prison sentences in 2017 were less than four months (Danish Prison and Probation Services 2018)). Within the last decades Denmark has also seen a large increase in the use of non-custodial sanctions that serve as alternatives to prison. The low imprisonment rate results in much fewer children experiencing paternal or maternal incarceration especially for longer periods of time (1.5% of Danish children experience paternal incarceration lasting at least 6 months compared to 8% of children in the United States) (Wildeman and Andersen 2015).Footnote 2

Second, Denmark has an extensive welfare state, which could alleviate some of the potential detrimental effects of paternal incarceration. Generally, there is a high level of redistribution within the Danish society (Causa and Hermansen 2019) and the comparatively generous social welfare benefits, including cash transfers in case of unemployment and illness, means that many families can keep poverty at bay while having only weak attachments to the labor market. For families of inmates there are even some measures put into place in order to help them financially (Smith and Jakobsen 2010). Denmark also has government funded education all through primary school to university, which should in principle make room for considerable educational mobility and render parental resources less influential in terms of their children’s educational outcomes.

The Danish case thus allows us to study effects of rather short spells of incarceration in a setting where financial cost associated with paternal incarceration are to a large extent offset by a generous welfare state and where paternal incarceration is generally rare. The short duration of paternal incarceration naturally results in less father-child separation, which would lead us to expect smaller effects in Denmark compared to countries where fathers are incarcerated for much longer periods of time. Additionally, the comparatively high levels of social benefits mean that financial strain on family resources brought on by an incarcerated father is likely to by smaller in the Danish context compared to settings with a less developed social safety net. But the relatively low prevalence of paternal incarceration could imply that paternal incarceration might be more heavily stigmatized and unexpected in the Danish context.Footnote 3 Previous research has found paternal incarceration to increase the risk of foster care placement and of facing criminal charges in Denmark (Andersen and Wildeman 2014; Wildeman and Andersen 2017).

The Sentencing Reform in 2000

The empirical strategy to estimate causal effects relies on plausibly exogenous variation in paternal incarceration introduced by a Danish sentencing reform. The reform, which came into effect on July 1st 2000, expanded the use non-custodial alternatives to prison through two channels and resulted in a sharp decline in the risk of being sentenced to prison after the reform and particularly so for offenders convicted of severe and/or repeated traffic violations.

First, the reform changed the use of community service as an alternative to prison for a wide range of offenses. Besides supervision from the Danish Prison and Probations Services a community service sentence involves unpaid work in public institutions such as libraries, museums, or the military. Offenders are sentenced to community service on the basis of an eligibility assessment conducted prior to the sentencing by the Danish Prison and Probation Services that consider employment, family relations, health, criminal history and personal motivation in their assessment (Lagoni and Kyvsgaard 2008). The scheme was introduced in 1992, but only for a very restricted number of offenses. On July 1st 2000 the sentencing policies were changed to expand the use of community service by (a) allowing major traffic offenders to be sentenced to community service rather than prison, and (b) making community service eligibility assessment mandatory for property offenders at risk of receiving their first prison sentence (Forslag til Lov om ændring af straffeloven (nr. 41) 1999)). But as Fig. 1 shows, the increase in the use of community service almost exclusively pertain to traffic offenders.

Second, the reform changed the use of alcohol-treatment programs as alternatives to prison for offenders convicted of serious/repeated drunk driving. The scheme was introduced in 1990, where drunk-drivers sentenced to less than 60 days in prison could apply for the program, which involved Antabus treatment and therapy, pay a fine and have their prison sentence suspended given that they did not commit new crime within two years (Nielsen and Kyvsgaard 2007). The reform in 2000 substituted the pardon-from-prison scheme with a scheme where offenders were sentenced to the program at court, hereby both expanding the use of the alcohol treatment program and reducing the degree of self-selection into the program.

Figure 2 (Panel A) shows that the sentencing reform in 2000 also led to an increase in the use of suspended sentences with alcohol treatment equivalent to the increase in community service sentences for serious/repeated drunk-drivers.Footnote 4 Major traffic offences not related to drunk driving (Panel B), on the other hand, only saw an increase in community service.

Development in prison and suspended sentences for major traffic offences. Figure shows share of all prison and suspended sentences for major traffic offences that results in either prison, suspended w. community service or suspended sentences w. alcohol treatment.

Overall, the 2000 sentencing reform was to a large extent targeted towards serious/repeated traffic offenders, who went from a certain prison sentence before the reform to having three different sentencing options after the reform, that is (1) prison sentence, (2) community service, and (3) alcohol treatment, as illustrated in Table 1.

Implications for the Margin of Treated and the Margin of Treatment

Relying on the sentencing reform has several implications for whom the findings of the paper apply to and for how the findings should be interpreted.

Margin of Treated

The reform almost exclusively replaced prison sentences with non-custodial alternatives for (serious) traffic offenders, and the findings thus apply to the children of this particular group of offenders. This raises the question of which margin of the distribution of offenders or incarcerated populations the serious traffic offenders represent. Two points are noteworthy here. First, at the time of the sentencing reform, prison sentences and suspended sentences were only an option for particularly severe traffic offences such cases with an extremely high blood alcohol content (BAC above 0.2%) or when following a prior offence, for which the driver’s license was suspended. This implies that we are not dealing with speeding, low-level drunk driving, running a red light, or other minor traffic violations. Second, being incarcerated for traffic offences is quite common for fathers in prison. 17% of incarcerated fathers were in prison due to traffic offences in 2013, which naturally represent a much lower level than what would have been the case prior to the introduction/expansion of the non-custodial alternatives for this group (Oldrup et al. 2016). These two points are reflected in the comparison between fathers convicted and sentenced to prison for different offence types in 1999 (see Table 7). Although fathers sentenced to prison for traffic offences are older, more likely to be native Danes, and slightly more advantaged in terms of socio-economic measures than property or violent offenders sentenced to prison, they generally resemble other fathers in prison (particularly those incarcerated for violent crime) much more than they resemble the general pool of traffic offenders with children, who receive fines.

Thus, although traffic offenders may be considered an atypical group of offenders, not routinely studied in the context of paternal incarceration, it is a significant group to consider. Both in Danish context–but also in the United States, where serious traffic offences may also result in jail or prison time.Footnote 5

Margin of Treatment

In this study, children whose fathers are sentenced to prison comprise the treatment group, and children whose fathers are sentenced to either of the non-custodial alternatives to prison comprise the control group. The treatment thus consists of roughly 30 days of prison (maximum 60 days), and traffic offenders would serve their sentence in low security “open prisons” with significant freedom within the prison and few barriers to the outside world. The routines in the Danish prisons are generally structured to resemble life on the outside with time for both work/education and leisure and with private cells. Although there is a strong focus on rehabilitation in the Danish prisons, programs to address potential substance abuse issues in prison were relatively sparse during the period and given the short duration of the prison sentences it is unlikely that the traffic offenders with alcohol abuse issues had the chance receive treatment that addressed these issues in prison.Footnote 6 Although the lengths of the incarceration may resemble for example jail (potentially pre-trial) incarcerations in the United States, is it important to highlight that the conditions under which the sentence is served are different. Furthermore, for incarcerated individuals and their family serving a sentence may also be a significantly different experience compared to being incarcerated pre-trial (Wakefield and Andersen 2020) even if the duration and other conditions of the incarceration are similar.

The fathers of the children who comprise the control-group are sentenced to either one of the two non-custodial alternatives. In the absence of paternal incarceration, the children in the control group are expected to benefit from ((a) not being separated from their father, (b) not being subjected to the same degree of stigma (non-custodial sanctions are easier to hide and potentially carry less stigma even if known), and (c) not experiencing the same degree of financial hardship and strain following the sanction as non-custodial sanctions have less severe consequences than incarceration for labor market attachment (Andersen 2014). However, in addition to the absence of paternal incarceration, the children in the control group may also benefit from either (a) successful treatment of a father’s alcohol issues (when fathers are sentenced to alcohol treatment programs), which may have positive effects on the home environment, or (b) any positive effects of a father participating in community service (e.g., establishing new pro-social ties that may positively impact the life course of offenders, Wermink et al. 2010). I address the issue in a robustness check (where I find that it is highly unlikely that findings are driven by positive effects of the alcohol treatment programs) and discuss the implications for the interpretation of the findings in the discussion (where I highlight the salience of considering community service as an alternative to incarceration).

Data and Method

Danish Administrative Data

For the analysis I make use of full population Danish administrative data made available by Statistics Denmark.Footnote 7 The administrative records contain unique identifiers on all residents in Denmark and enable me to link (1) family members and (2) information from different societal institutions. The administrative records go back as far as 1980 essentially enabling the creation of 30–40 years of panel data (for a general description of the Danish administrative data, see Andersen 2018). For the purpose of this study, the link between family members is crucial as it allows me to identify the father-child pairs, but the linking across different domains–from the criminal justice system to the educational system–is also essential for the analysis. The two most central sources of data used here come from The Central Criminal Register, which supply information on convictions, and the Danish Ministry of Education, who supplies information on for example grades from compulsory school (from 2002) and highest achieved education.

Analytical Sample

I arrive at my analytical sample through inclusion criteria pertaining to (a) the conviction, and (b) the children (see Table 8 for a stepwise sample restriction). The conviction must meet the following three criteria to for the child to be included in the sample. First, the conviction must result in either a prison sentence or a suspended sentence (with community service or alcohol treatment) and fall within one year before and after the reform was implemented (on July 1st 2000). The one-year cut off is chosen to achieve the narrowest possible window around the reform to minimize the risk of general trends skewing the comparison between those whose father was convicted before and after the reform, while avoiding seasonal variation in crime to affect the before-after comparison. Second, since I study paternal conviction, it must be a father (not a mother) who was convicted (this drops roughly 10% of the sample). Third, I restrict my analytical sample to only include children whose father was convicted of traffic offences since the sentencing reform almost exclusively changed the risk of receiving a prison sentence for this group of offenders.

Regarding the inclusion criteria pertaining to the children, I restrict the analytical sample to only include children born between 1988 and 1995, who were aged between 5 and 11 at the time of paternal conviction. The restriction on cohort is necessary to ensure that educational outcomes measured by the end of compulsory school (9th grade) should be available for all children and the restriction of age ensures that the before and after groups are balanced in terms of age.Footnote 8 This leaves me with an analytical sample of 2443, and since some children appear with more than one paternal conviction that meet the criteria this number covers 2215 individual children.

Variables

Paternal Incarceration

The explanatory variable of interest is paternal incarceration, for which I use a binary indicator of whether the child’s father was sentenced to prison (1) or sentenced to one of the non-custodial alternatives (0).Footnote 9 If sentenced to prison prior to the reform the average sentence length in the sample is 32 days. The measure only refers to a specific conviction within the chosen time window around the reform, and it does not measure whether a child has ever experienced paternal incarceration. To examine effects of first-time paternal incarcerations I also conduct the analysis on a sample of children, who have not previously experienced any paternal incarceration lasting at least a week, and I refer to this as the first-time sample.

Educational Outcomes

The organization of the Danish educational system consists of 10 years of compulsory schooling (grade 0–grade 9) in which primary and lower secondary school is integrated in a single structure. After finishing compulsory schooling adolescents are free to pursue further upper secondary education, either in a vocational or a three-year college-bound track (similar to high school), or not. Children usually start grade 0 in the year they turn 6 and finish 9th grade the year they turn 16, but late school starting age and grade retention will result in deviations from this standard schooling trajectory. I focus on educational outcomes from the end of compulsory schooling (9th grade) because it is the lowest level of completed education that one can obtain in Denmark and a significant crossroad within the Danish educational system. In this way, I hope to capture educational outcomes at a margin, where even children with a weak attachment to school are represented and have some variation in outcomes in a way, they might not have if the focus was on for example grades or completion of high school or college.

In the analysis I use the following three measures of educational outcomes: (1) children’s grades by the end of 9th grade, (2) the proportion of compulsory grades that they obtain and (3) whether they complete compulsory schooling. The first variable is thought to serve as an indicator of academic achievement (and the outcome most closely aligned with cognitive abilities), the second is thought to give us an indication of level of participation in school, and the third serves as a marker of not having completed what should be the minimal level of education.Footnote 10 Of the three the latter is thought to be the strongest marker of future life chances.

Standardized GPA

By the end of 9th grade two sets of grades are given. One is the grades from the exams, which are either oral or written. The other set is the end-of-year grades based on the student’s performance throughout the school year. I construct two measures of grade point average (GPA)–one for exam grades and one for end-of-year grade—standardized within year.Footnote 11 I use both exam and end-of-year measures because I suspect that end-of-year grades could be more affected by potential teacher-bias, since end-of-year grades are based solely on the classroom teacher’s assessment whereas exams are graded in collaboration with an external teacher with no prior knowledge of the child.

Proportion of Grades Obtained

I also construct measures of the proportion of the compulsory grades that the student has obtained. This is done because not all students obtain a full set of grades–some have not obtained any grades at all–and this measure captures how close children are to fully completing compulsory school and exams. Not obtaining grades can come about if children do not attend school, skip exams, are placed in special schools or if the teacher decide against grading. Among children in the analytical sample as many as 18% do not have any grades registered at all. To ensure that their lack of appearance in the grade register is not due to a misregistration, delay or because they were not in the country at the time, I only include children living in Denmark on January 1st of year they turned 16, who has not completed any further education that requires completing compulsory schooling, and who are not still enrolled in compulsory school by 2015. About a third of the children who do not appear in the grade register fit these criteria and are included in the proportion of grades variables.Footnote 12

Not Completing Compulsory Schooling

Finally, I include a measure of whether children have completed compulsory schooling (9th grade) by age 20. To be marked as “not completed” the child has to be registered as having completed less than 9th grade (or have missing highest achieved education, due to the high quality of the data) by October 1st the year they turn 20 and not previously have been registered with any higher education.Footnote 13

Instrumental Variable Approach

I use an instrumental variable (IV) approach to exploit the plausibly exogenous variation in the risk of experiencing paternal incarceration imposed by the 2000 sentencing reform (similar to the approach used by Andersen and Wildeman 2014). I use timing of paternal conviction–that is, before or after the reform came in effect on July 1st, 2000–as an instrument (Z) for paternal incarceration. This approach entails that only the variation in paternal incarceration induced by the sentencing reform is leveraged and that the variation that may be correlated with unobservables and may otherwise bias the results is bypassed. The IV approach consists of two steps, which illustrates this logic well:

First, I use the timing of conviction (Z) and a vector of covariates (X) to predict the risk of paternal incarceration. Second, I use the predicted risk of paternal incarceration from the first stage to estimate the causal effect of paternal incarceration on children’s educational outcomes. The interpretation of the Two Stage Least Square (2SLS) estimate (β1) as a causal effect rests on the validity of the instrument (Angrist 2006).

Instrument Validity

The validity of timing of paternal conviction as an instrument for paternal incarceration depends on how well it satisfies two key features/assumptions.Footnote 14 First, timing of paternal conviction must be a relevant instrument in the sense that it affects the risk of paternal incarceration. Figures 1 and 2 presented above show that this is clearly the case and the first stage results (Table 4) show that having a father that was convicted after the reform decreases the risk of paternal incarceration by 72 percentage points. Second, the timing of paternal convictions has to be exogenous–that is, timing of paternal conviction does not have an impact on the outcomes other than through the first stage and timing of paternal conviction is as good as random (Angrist and Pischke 2009).

In this light, one need to consider the possible threats to instrument exogeneity. First, time trends might lead to different circumstances for children whose father was convicted before or after the reform, although using a narrow time window around the reform should minimize this risk. Second, the announcement of the reform might lead some prosecutors or defenders to delay/rush through some cases because they want a specific outcome or the reform might change the process of reaching a conviction (e.g., via plea bargaining). While there is some evidence of the former process, there is no tradition for plea bargaining within the Danish system akin to what exists in the United States and in the Anglo-Saxon systems, and the reform did not result in fewer or more cases going to trial or resulting in a guilty verdict, nor in greater/lesser discrepancy between initial charge and the crime type for which a conviction is reached (figures are available upon request). Third, potential offenders might know of the changed sentencing practices through media coverage and change their behavior accordingly and commit crime (that they would otherwise have abstained from) as the sentence becomes lighter. I perform robustness checks to examine the possibility of announcement bias and time trends driving the results, and find no evidence of this, and although it is difficult to rule out some degree of self-selection completely, there are no indicators of a systematic change in the composition of offenders and children across the reform.Footnote 15

If timing of paternal conviction is indeed as good as random and the reform therefore introduces an exogenous shock to the risk of experiences paternal incarceration, then we should expect the children and their fathers to be similar before and after the reform. Testing differences in background characteristics for children whose fathers were convicted before/after the reform does provide an indicator (although not a decisive test) of how similar the before/after groups are. Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for the pre-reform and post-reform groups and tests how balanced the sample is across the reform on a standard set of background factors (all determined prior to conviction and included as covariates in the regressions) including child demographics and socioeconomic status, criminal history, and basic demographics of both parents (see Table 9 for and equivalent table for the first-time sample). There are a few significant differences in background characteristics between the before and after group. Some of these differences indicate that children in the before-group were more disadvantaged (like paternal disability pension and prior prison sentences) but others indicate otherwise (like residential situation and immigrant background), and overall the table does not give us cause to suspect that groups differ in systematic ways.Footnote 16

Results

Baseline Associations

In line with prior research I find that paternal incarceration is generally associated with worse educational outcomes within a broad population of Danish children. This pattern is clear from Panel A in Table 3, which shows the differences in educational outcomes between children experiencing any length of paternal incarceration (including short stays in jail lasting less than 24 h) and children with no paternal incarceration for cohorts born 1988–1995. On average children whose father has been incarcerated score significantly worse than children whose father has never been in jail or prison on all educational outcomes. They score roughly 0.4 standard deviations lower than children with no paternal incarceration on the GPA-measures, only obtain grades in 87% of subjects rather than 94%, and almost 5% have not completed compulsory schooling by age 20 compared to 1.5% of children with no paternal incarceration.

But the two groups compared in Panel A most likely differ on a wide range of other characteristics besides the experience of paternal incarceration–paternal prior criminal record being just one of them–which could drive the observed differences educational outcomes. Some of these differences (i.e. sources of selection) can be circumvented simply by directing our attention to the analytical sample, which only includes children of fathers convicted of traffic offences, and comparing educational outcomes among children whose father is sentenced to prison to children whose father is sentenced to a non-custodial alternative (Panel B). Results show much smaller differences in standardized GPA between the two groups than observed in Panel A, with both scoring 0.4–0.5 standard deviations below the overall mean, and only the difference in end-of-year GPA is statistically significant. Of the children whose father is sentenced to prison, as many as 8% have not completed compulsory schooling by age 20, which is almost twice as many in the non-custodial group, and they also obtain grades in much fewer subjects (81% vs. 87%). However, as sentencing outcomes are based on eligibility assessment and judges’ discretion, this simple comparison between children whose father was sentenced to prison vs. the non-custodial alternatives may still be driven by selection and cannot be interpreted as causal effects of paternal incarceration.

Main Results

Table 4 presents the first stage estimates for the sample of children with minimum one non-missing educational outcome and shows that having a father that was convicted after the reform relative to before decreased the risk of paternal incarceration substantially (72 percentage points for the main sample and 82 percentage points for children who have had no prior paternal incarceration). This highlights that the sentencing reform did indeed provide a substantial shock to the risk of experiencing paternal incarceration.

Table 5 presents the main results from OLS and IV models for both the main sample and the sample of children with no prior paternal incarceration. The first two rows present OLS and IV estimates of effects of paternal incarceration on the standardized GPA-measures. In the OLS models there are no statistically significant differences in GPA between children whose father are sentenced to prison and children whose father are sentenced to non-custodial alternatives, when controlling for differences in child and parental characteristics. In the IV models, estimates are both very close to zero and statistically insignificant suggesting that there are no effects of paternal incarceration on GPA–at least not for the children who do participate in school and receive grades. These results also hold for the sample of children with no prior paternal incarceration.

For the second set of outcomes the results from the IV models show that paternal incarceration decreases the proportion of grades obtained with 4.5 percentage points overall, and 5.7 percentage points for the proportion of exam grades obtained–representing a 5% and 6% change relative to the baseline in group of children whose father are sentenced to non-custodial alternatives. The effect on proportion of end-of-year grades obtained is smaller and only marginally statistically significant. Effects of first-time paternal incarceration are very close to the estimated main effects, which suggests that paternal incarceration is not uniquely harmful the first time it occurs.

The third set of outcomes (and most likely the most consequential outcomes) are whether the child has completed compulsory schooling by age 20. Here I find rather substantial effects in the IV model with paternal incarceration estimated to increase the likelihood of not completing compulsory schooling by 4.5 percentage points by age 20 representing substantial increases relative to the baseline of 4.2%. Estimates are similar in size for those with no prior paternal incarceration.

Jointly, these estimates suggest that while paternal incarceration does not affect the academic performance (GPA) of children, who do participate in compulsory schooling and receive grades (which aligns with the mixed previous literature regarding cognitive and academic skills), the educational participation and completion is significantly and negatively affected. These latter outcomes may be driven by, not so much to cognitive skills, but rather non-cognitive skills and non-academic processes, which are also significant in determining educational outcomes (Farkas 2003).

Generally, IV estimates presented in Table 5 are very similar to the equivalent OLS estimates, which indicate that once the sample is restricted to children of fathers who have committed the same type of offences, there is little selection on unobservables that separates those exposed to paternal incarceration and those that do not. This means that OLS estimates only appear to be slightly biased for this specific population of children.

Heterogenous Effects

Table 6 presents IV estimates of the effect of paternal incarceration for boys and girls and generally support the hypothesis that boys are more severely impacted by paternal incarceration than girls.

The observed statistically significant effects of paternal incarceration appear to be primarily driven by the boys in the sample, although estimates for girls generally go in the same direction and I cannot reject the null hypothesis that estimates effects are the same across gender. Paternal incarceration is estimated to reduce the proportion of exam grades obtained by 7.3 percentage points for boys, and 4.2 percentage points for girls–the latter is only marginally significant. Likewise paternal incarceration is estimated to increase the risk of not completed compulsory schooling by age 20 with 5.6 percentage points for boys relative to 3.4 percentage points for girls. Furthermore, for first-time paternal incarceration the differences in gender are much larger and also statistically significant indicating that gender disparities in the consequences of paternal incarceration are more pronounced for first-time paternal incarceration. This could be tied to differences in coping styles between boys and girls, where girls may be more prone to avoidant coping styles, which could mask initial responses to paternal incarceration and require repeated paternal incarceration or prolonged periods of instability to manifest themselves in poorer educational outcomes.

Robustness Analysis

The validity of the main results presented above rests on the instrument (i.e., timing of paternal conviction) being exogenous. Some potential threats to instrument exogeneity were highlighted in Methods section, and in order to assess whether they should be causes of concern I present a series of robustness checks.

First, a concern could be the possibility of an announcement bias leading certain cases to be postponed or moved forward across the reform to achieve certain outcomes. There is some evidence of announcement bias as there is a drop in convictions for drunk driving two months prior to the July 1st 2000 and an increase in the two months after (Andersen and Wildeman 2014). I check whether my results are sensitive to the exclusion of two months immediately before and immediately after the reform and present the results from the “donut”-specification in Table 11. The results are overall remarkably similar to the main estimates indicating that the estimates effects are not driven by announcement bias.

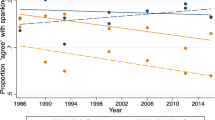

Second, another concern could be that general time trends for example in the development in educational outcomes could drive the effect seen in the main estimates. To address this, I present reduced form estimates (i.e., from models regressing educational outcomes on a before/after reform dummy) from several placebo samples constructed around an artificial reform date. For the 1999 placebo sample, children whose father was convicted between July 1st 1998 and June 30th 1999 are categorized as the before group, and children whose father was convicted between July 1st 1999 and June 30th 2000 are in the after group despite no sentencing reform taking place on July 1st 1999. Estimates are presented in Fig. 3 and show that reduced form estimates are virtually zero for all years for the standardized GPA (including 2000), but estimates for the other outcomes are neither as large as nor statistically significant in any other years than in 2000, where the actual reform was implemented.

Finally, a third issue concerns the interpretation of the estimates as causal effects of paternal incarceration. By using the 2000 reform I have essentially grouped together two distinct control groups with two distinct experiences–that is, children whose father is sentenced to community service and children whose father is sentenced to non-custodial alcohol treatment program. While it is likely that the most significant aspect of having a father sentenced to community service rather than prison is that the father avoids prison, a father’s participation in an alcohol treatment program may also have a significant impact on the child and the child’s home environment above and beyond avoiding time in prison. Children whose father is sentenced to alcohol treatment both avoid paternal incarceration and experience their father getting a treatment, which addresses issues of alcohol abuse that may have taken its toll on family life before. This implies that the negative effects seen above might not solely be due to paternal incarceration but also stem from the possible positive effects of alcohol treatment that some children in the control group experience together with avoiding paternal incarceration.

To address this concern, I conduct a robustness check in which I remove those sentenced to alcohol treatment from the sample. However, in order to maintain a balanced before and after sample, I match those sentenced to alcohol treatment (after the reform, N = 411) with a comparable group convicted before the reform and remove this matched group (N = 411) from the sample as well.Footnote 17 I use propensity score matching with detailed measures of crime type and criminal history (including separate measures for drunk driving history) in addition to the paternal characteristics used elsewhere in the analysis to identify the group convicted before the reform, which most closely matches those sentenced to alcohol treatment after the reform. This robustness check thus seeks to identify effects of paternal incarceration by using solely those sentenced to community service as the control group. Results (presented in Table 12) show that effects persist in the restricted sample and estimates are in fact numerically larger than the original estimates, which suggests that any benefits of alcohol treatment are not significant drivers of the effects observed in the main sample.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this paper I have used plausibly exogenous variation in the form of a sentencing reform in 2000, which expanded the use of non-custodial alternatives to prison, to estimate the effect of paternal incarceration on children’s educational outcomes related to finishing compulsory schooling. More specifically, I studied the effect on standardized grade point average, proportion of grades obtained, and the risk of not completing compulsory schooling (9th grade).

I found that paternal incarceration decreases the proportion of grades obtained in the compulsory subjects by the end of 9th grade and increases the likelihood of not completing compulsory schooling. Although these outcomes are measured at the end of compulsory schooling (9th grade) and later, it is likely that the damage of paternal incarceration reflected in the effects on these outcomes has occurred earlier in the school course. Not completing compulsory school and not obtaining a full set of grades are quite severe outcomes and are most likely connected to prolonged periods of absence, need for special education, poor academic performance or destructive behavior possibly leading teachers and children to give up in terms of completing compulsory schooling. Previous studies on early educational outcomes have reported negative associations between paternal incarceration and non-cognitive skills, grade retention and special education placement (Haskins 2014; Turney and Haskins 2014) which are most likely related to the outcomes in this paper. Given that paternal incarceration is not found to have any effects on grade point average it seems unlikely that cognitive or academic abilities that are affected by the experience, rather it appears to be the chances of putting those abilities to use that are severely hampered by the experience of paternal incarceration. The current study thus adds to the already mixed literature on educational outcomes relating to cognitive and academic skills by finding null-effects on GPA while applying a rigorous research design well equipped at ruling out (unobserved) selection and estimating causal effects of paternal incarceration.

Furthermore, the findings from this study thus highlights the added benefits of going beyond traditional measures of educational outcomes–such as grades and highest completed education–since they might not capture detrimental effects for the children most likely to experience and to be impacted by paternal incarceration. In fact, bridging the findings from the current study with null-findings on educational outcomes in prior studies in similar contexts (Bhuller et al. 2018; Dobbie et al. 2018) could suggest that those most affected by paternal incarceration are children at the margin of participating in and completing even the minimal level of education. Children with even limited paternal criminal justice contact have very poor educational outcomes (Andersen, 2016), and when paternal incarceration further impedes on these outcomes it is likely to take the form of dropping out of compulsory school rather than getting a grade lower or not completing college. Focusing on completed education at high school or even college level could then obscure effects at the other end of the distribution.

Compulsory school may thus be a potential arena for intervention as these children may lose contact with the educational system earlier than most other kids. Dropping out of school means that there is no other institutional contact until somethings goes wrong–that is, the next time these children will be in touch with social institutions and possibly a target for intervention is through the social service system, health care system, and potentially the criminal justice system themselves given the high rate of criminal justice involvement among school dropouts. However, given that stigmatization and teacher bias (Wildeman et al. 2017) could be significant drivers of the detrimental consequences of paternal incarceration in Denmark, such school level interventions would need to approach this subject with much caution.

The findings also show an indication that effects on educational outcomes are mainly driven by the boys in the sample. This suggests that boys are more vulnerable to paternal incarceration than girls or respond to this experience differently and in ways that impacts their early educational outcomes more negatively. Coupled with previous research in the area (Cooper et al. 2011; Haskins, 2014) it is likely that the effects on these educational outcomes go through a decrease in non-cognitive skills or increase in behavioral problems following paternal incarceration, where results also show gendered effects. Broadening the range of outcomes to include measures such as internalizing behavior, depression or quality of social relationships could be useful in terms of understanding whether paternal incarceration affects only boys or whether girls just respond differently and in ways that are not as harmful for their school performance.

By studying the effects in Denmark, I not only take advantage of administrative data uniquely suited for studying intergenerational effects (similar to the Swedish and Norwegian data used in Bhuller et al. 2018; Dobbie et al. 2018)) I also indirectly gain insight into which mechanisms are most plausibly driving the effects given the specific penal and social context. Given the short durations of paternal incarceration studied here, and the extensiveness of the social safety net in Denmark, it is less likely that the negative consequences run through substantial decreased paternal attachment or financial strain brought on by incarceration, and rather more likely that experienced or perceived stigmatization is the central mechanism. However, the rarity and potentially unanticipated nature of the event may contribute to making it particularly hard for the children, who do experience it, although paternal incarceration may not to the same degree as elsewhere contribute to perpetuating broader inequalities at the population level.

While reliance the on a Danish sentencing reform allows the study to leverage exogenous variation in the likelihood of having a father sentenced to prison, it does put some limitations in the generalizability and the interpretations of the findings. First, the findings pertain to children of (severe) traffic offenders, a group that is not routinely studied in the context of paternal incarceration and may be considered somewhat atypical. However, traffic offences are not uncommon offences among inmates in Denmark (Oldrup et al. 2016), and the fathers incarcerated for traffic offenders generally resemble other inmates more than minor traffic offenders. Second, the interpretation of the results is complicated by the reform expanding the use of two types of non-custodial alternatives (community service and alcohol treatment). However, a robustness check which attempts to provide a cleaner comparison between children whose father was sentenced to prison with children whose father was sentenced to community service (due to the reform) finds similar (and slightly stronger) effects, which indicates that any positive effects of paternal alcohol treatment are not the drivers of the overall effects. Finally, to the extent that community service benefits children above and beyond avoiding negative effects of paternal incarceration (i.e., community service may have pro-social effects on offender and their families), the findings may reflect both negative effects of paternal incarceration and any positive effects of community service. However, since offenders at the margin of receiving a prison sentence would rarely just be free to go in the absence of a prison sentence (that is, the alternative sanction would most often be parole with some conditions) the relevant margin when estimating effects of would not necessarily be to compare paternal incarceration with no criminal justice intervention. In fact, since community service is widely and commonly alternative to prison sentences (Faraldo Cabana 2020), it may be a particularly relevant comparison for policy perspective–even if part of the negative effects attributed to paternal incarceration may go through an added benefit of a father being sentenced to community service.

In summation, paternal incarceration increases the likelihood of not completing compulsory schooling and decreases the likelihood of obtaining full set of grades when finishing 9th grade. In combination these measures point to an increased risk of school failure, dropping out and being only marginally involved in the educational system. Not completing compulsory schooling, in particular, makes further education and employment beyond unskilled labor highly unlikely. The results highlight that paternal incarceration plays a role in enhancing the transmission of disadvantage from one generation to another, and points to the benefits of the use of non-custodial alternatives to prison for the children of offenders.

Notes

A parallel point regarding labor market participation and earnings is made by Dobbie and colleagues (2018), when they find little evidence of effects parental incarceration on overall earnings, but find effects in the far left tail of the earning distribution, suggesting that “…parental incarceration has a larger impact on children at the margin of any employment, with relatively little impact on children with higher potential earnings”(Dobbie et al., 2018, p. 21). They furthermore find, that it is the most disadvantaged children in their sample, who drive the observed effects of parental incarceration on employment, teen convictions and teen pregnancy (Dobbie et al., 2018).

Estimates from Denmark are based on full population administrative data on all incarceration spells. Estimates from the United States are based on the results from Wildeman (2009), which uses the Survey of Inmates of State and Federal Correctional Facilities to estimate the cumulative risk of paternal imprisonment in state and federal prisons (that is, jail incarcerations are not included). Since the minimum time served in United States state and federal prisons is 6 months, the authors note that comparing the risk of paternal incarceration lasting at least 6 months in Denmark is the relevant comparison to the risk of paternal imprisonment in the United States (Wildeman & Andersen, 2015).

The low imprisonment rate also implies that those who do end up in prison are likely to be a highly select and disadvantaged group relative to a context where incarceration is more prevalent, which might also have implications for the estimated effect. It could both be speculated that highly disadvantaged groups are more (Dobbie et al., 2018) or less (Turney, 2017) impacted than more advantaged groups.

The data on convictions, obtained from Statistics Denmark, does not contain information on whether the suspended sentence involved alcohol treatment. However, suspended sentences given for drunk driven that does not involve community service will instead involve alcohol treatment (Nielsen & Kyvsgaard, 2007, p. 4). Furthermore, as a consequence of the pardon-from-prison scheme in place prior to the reform some are registered with a prison sentence but did in fact get pardoned as part of the program, but I am unable to identify this group in the data.

Within the United States, there is significant variation across states in sanctions for drunk driving and other traffic offenders. Overall, it is not uncommon for drunk driving (with high BAC) to results in jail or prison time ranging from a few days to several months depending on the BAC-level and prior offences.

Inmates committed to escaping substance abuse could be placed in special wards, where trained staff would provide help and support and regular testing. From 2007 the Danish Prison and Probation Services have been obliged to offer treatment for substance abuse issues in all facilities and within a short amount of time from the start of incarceration.

The de-identified individual-level data used to arrive at the findings may be obtained through Statistics Denmark following a clearance process. For information on the process and the accessibility of Danish registry data, see http://www.dst.dk/ext/645846915/0/forskning/Access-to-micro-data-at-Statistics-Denmark_2014--pdf.

For general information about access to Danish registry data through Statistics Denmark, including information on how to apply for data access, see http://www.dst.dk/en/TilSalg/Forskningsservice.

Data on grades from primary school are available from 2002 onward, but to avoid reliance of on the two first years, which suffer from a relatively high level of missing data, the eldest children included are born in 1988 and should finish primary school in 2004 (following a standard schooling trajectory).

Children are included in the analytical sample on the basis of conviction, which may have introduced discrepancies between children registered with paternal incarceration and children actually experiencing paternal incarceration. Such discrepancies can be caused by both the pardon-from-prison alcohol treatment scheme operating before the reform, and from the fact that we are dealing with suspended sentences meaning that the father will have to go to prison if he does not fulfill the conditions for his sentence. These are cases of treatment migration and dilution, which is unlikely to have occurred at random, but as this only serves to minimize differences between the groups (Angrist, 2006), it is most likely that this would lead to underestimated effects of paternal incarceration.

Attention within Danish education policy has long been directed toward bringing down the share of young adults who only complete primary school, it is only recently that attention has been directed towards the fact that not everyone achieve this minimal level of education (Wittrup, 2017).

Included in the exam GPA-measure are grades in Danish (written, oral and grammar), Math (written), Science and English (oral). For end-of-year GPA the included grades are in Danish (written, oral and grammar), Math (oral, written), Science, English (oral) and a project assignment. These subjects are not the only ones in which the students receive grades. They are, however, the only subjects for which grades are given throughout 2002–2015. Equal weight is given to all the grades, which means that Danish as a subject is given three times the weight as English in constructing the GPA. I standardize measures within year to avoid general trends in grading practices to skew results and because the grading scale changes during the period in which the outcome is measured (ranging from 0 to 13 with a passing grade of 6 until 2007 and ranging from –3 to 12 with a passing grade of 2 from 2007 and onwards).

In the population of children born between 1988–1995, 8% do not appear with any grades in the grade register, but only 12% of the children with missing grades are in the country the year the turn 16 and do not complete further education.

The Danish educational registers are of high quality when it comes to education started/completed at the Danish educational institutions. For education achieved abroad (for immigrants for example) information on highest achieved education is flawed, but it is highly unlikely that such misregistration would pertain to the sample of children, who are all in Denmark at ages 5–11, where their father is convicted.

Another necessary assumption for the IV approach is monotonicity, which is the assumption that the instruments only affect the treatment variable in one direction. This means that the reform must decrease the risk paternal incarceration for all and there can be no defiers whose risk of paternal incarceration increase following the reform. As the suspended sentences (w. community service or alcohol treatment) where not available prior to the reform the existence of defiers in terms of sentencing is not plausible.

There is a small increase in the number of convictions between the before and after groups (see Table 1), but this increase mainly occurs just around the reform and cannot be due to people changing behavior after the reform since it takes on average six months from crime to convictions (for traffic offenders at the time).

These minor differences do in no way drive our results. Table 10 shows that the results are very robust to including the covariates in the IV regressions.

Excluding only the children whose father gets sentenced to alcohol treatment is not a viable strategy, as this would entail only choosing the group of children after the reform, who are less likely to have fathers with alcohol abuse, to serve as controls for the full group of fathers sentenced before the reform, which could lead to significant bias.

References

Andersen SH (2014) Serving time or serving the community? exploiting a policy reform to assess the causal effects of community service on income, social benefit dependency and recidivism. J Quant Criminol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9237-2

Andersen LH (2016) How childrens educational outcomes and criminality vary by duration and frequency of paternal incarceration. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 665(1):149–170. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716216632782

Andersen LH (2018) Danish register data: flexible administrative data and their relevance for studies of intergenerational transmission. In: Eichelsheim VI, van de Weijer S (eds) Intergenerational continuity of criminal and antisocial behavior: an international overview of studies. Routledge, New York, pp 28–43

Andersen SH, Wildeman C (2014) The effect of paternal incarceration on children’s risk of foster care placement. Soc Forces 93(1):269–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sou027

Angrist JD (2006) Instrumental variables methods in experimental criminological research: what, why and how. J Exp Criminol 2(1):23–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-005-5126-x

Angrist JD, Pischke J-S (2009) Mostly harmless econometrics: an empiricist’s companion. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Besemer S, van der Geest V, Murray J, Bijleveld CCJH, Farrington DP (2011) The relationship between parental imprisonment and offspring offending in England and the Netherlands. Br J Criminol 51(2):413–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azq072

Bhuller M, Dahl GB, Loken KV, Mogstad M (2018) Intergenerational effects of incarceration. AEA Papers and Proceedings 108:234–240. https://doi.org/10.1257/pandp.20181005

Bowlby J (1985) Attachment and Loss Vol Separation Anxiety and Anger . The Hogarth Press, London

Causa O, and Hermansen M (2019) Income redistribution through taxes and transfers across OECD countries. OECD Economics Department WorkingPapers. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1787/bc7569c6-en.

Cho RM (2009) The impact of maternal imprisonment on children’s educational achievement. Journal of Human Resources, 44(3), 772–797. Retrieved from http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=trueanddb=bthandAN=43608259andsite=ehost-live

Cooper CE, Osborne CA, Beck AN, McLanahan SS (2011) Partnership instability school readiness and gender disparities. Sociol Educ 84(3):246–259

Dallaire DH, Ciccone A, Wilson LC (2010) Teachers’ experiences with and expectations of children with incarcerated parents. J Appl Dev Psychol 31(4):281–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2010.04.001

Danish Prison and Probation Services. (2018). Statistik 2017. Retrieved from https://www.kriminalforsorgen.dk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/kriminalforsorgens-statistik-2017-3-udgave.pdf

Dennison S, Besemer K, Low-Choy S (2019) Maternal Parenting Stress Following Paternal or Close Family Incarceration: Bayesian Model-Based Profiling Using the HILDA Longitudinal Survey. J Quant Criminol. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09430-z

Dobbie W, Grönqvist H, Niknami S, Palme M, and Priks M (2018) The Intergenerational Effects of Parental Incarceration (NBER Working Paper No. 24186). Retrieved from http://www.nber.org/papers/w24186

Faraldo Cabana P (2020) Paying off a fine by working outside prison: on the origins and diffusion of community service. Eur J Criminol 17(5):628–646. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370818819691

Farkas G (2003) Cognitive skills and noncognitive traits and behaviors in stratification processes. Ann Rev Sociol. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.29.010202.100023

Forslag til Lov om ændring af straffeloven (nr. 41) (1999). Retrieved from https://www.retsinformation.dk/Forms/R0710.aspx?id=87866

Foster H, Hagan J (2009) The mass incarceration of parents in America: issues of race/ethnicity, collateral damage to children, and prisoner reentry. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 623:179–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716208331123

Geller A, Cooper C, Garfinkel I, Schwartz-Soicher O, Mincy R (2012) Beyond Absenteeism: Father Incarceration and Child Development. Demography 49(1):49–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-011-0081-9

Goffman E (1963) Stigma: notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall, New Jersey

Hagan J, Dinovitzer R (1999) Collateral consequences of imprisonment for children, communities, and prisoners. Crime Justice 26:121–162. https://doi.org/10.1086/449296

Hagan J, Foster H (2012) Intergenerational educational effects of mass imprisonment in America. Sociol Educ 85(3):259–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040711431587

Haskins AR (2014) Unintended consequences: effects of paternal incarceration on child school readiness and later special education placement. Sociol Sci 1:141–158. https://doi.org/10.15195/v1.a11

Haskins AR (2016) Beyond boys’ bad behavior: paternal incarceration and cognitive development in middle childhood. Soc Forces. https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/sow066