Abstract

Objectives

This exploratory study examines if causal mechanisms highlighted by criminology theories work in the same way to explain both ideologically motivated violence (i.e., terrorism) and regular (non-political) homicides. We study if macro-level hypotheses drawn from deprivation, backlash, and social disorganization frameworks are associated with the likelihood that a far-right extremist who committed an ideologically motivated homicide inside the contiguous US resides in a particular county. To aid in the assessment of whether criminology theories speak to both terrorism and regular violence we also apply these hypotheses to far-right homicide and regular homicide incident location and compare the results.

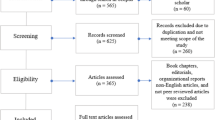

Material and methods

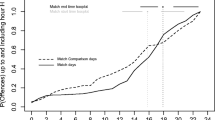

We use data from the US Extremist Crime Database (ECDB) and the FBI’s SHR to create our dependent variables for the 1990–2012 period and estimated a series of logistic regression models.

Conclusions

The findings are complex. On the one hand, the models we estimated to account for the odds of a far-right perpetrator residing in a county found that some hypotheses were significant in all, or almost all, models. These findings challenge the view that terrorism is completely different from regular crime and argues for separate causal models to explain each. On the other hand, we estimated models that applied these same hypotheses to account for the odds that a far-right homicide incident occurred in a county, and that a county had very high regular homicide rate. Our comparison of the results found a few similarities, but also demonstrated that different variables were generally significant for each outcome variable. In other words, although criminology theory accounts for some of the odds for both outcomes, different causal mechanisms also appear to be at play in each instance. We elaborate on both of these points and highlight a number of important issues for future research to address.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This paper compares the characteristics of counties where FRPs resided to counties where they did not reside. It does not compare the counties where FRPs resided to counties where far-left or Al Qaeda affiliated perpetrators who also committed ideologically motivated violence resided. Please see Chermak et al. (2015) for an in depth investigation of the latter issue.

As outlined in prior work (Freilich et al. 2014; see also Freilich et al. 2009), the far-right is operationalized as individuals or groups that subscribe to aspects of the following ideals: “… [far-rightists are] fiercely nationalistic (as opposed to universal and international in orientation), anti-global, suspicious of centralized federal authority, reverent of individual liberty (especially their right to own guns, be free of taxes), believe in conspiracy theories that involve a grave threat to national sovereignty and/or personal liberty and a belief that one’s personal and/or national “way of life” is under attack and is either already lost or that the threat is imminent (sometimes such beliefs are amorphous and vague, but for some the threat is from a specific ethnic, racial, or religious group), and a belief in the need to be prepared for an attack either by participating in or supporting the need for paramilitary preparations and training or survivalism. Importantly, the mainstream conservative movement and the mainstream Christian right are not included.”

Hamm (2007; see also Smith and Damphousse 2009) found that the far-right and Islamic jihadists commit different crime types in the United States. Far-right terrorists have been found on average to be older, and more likely to be male, religious, poorer and less educated and to operate in rural areas in the US compared to far-left terrorists (Gruenewald et al. 2013a, b; Handler 1990; Hewitt 2003; Smith 1994; Smith and Morgan 1994).

We recognize the critique that FRPs may be transients who recently moved into their residence and were not influenced by the characteristics of the county to which they just moved. We discuss how we addressed this important issue in FN 12 in the data and methods section.

Lyons (2007) Chicago hate crimes’ study found that anti-white hate crimes were more common in socially disorganized neighborhoods, while anti-black hate crimes occurred in organized areas. Although, almost all the FRPs in our study are white, we expect our findings will differ from Lyons results. First, we are focusing on homicides, while Lyons study excluded homicides. Lyons concludes that anti-black hate crimes occurred because white youths were “defending” their neighborhoods that were changing demographically (from white to more diverse). But, we expect that whites in changing neighborhoods would encourage actions like “routine” assaults or vandalism to “defend” their area (Freilich et al. 1999). Many whites, we suspect, would oppose the commission of exceptionally brutal assaults and homicides that may generate (negative) media coverage that could undermine their local support. Second, in addition to anti-minority hate homicides, our study also included other large categories of incidents such as anti-government homicides. Lyons did not study these types of crimes. Third, most hate crimes are committed by non-extremist youths acting in groups. Thus, few of the perpetrators in Lyons study were far-rightists, while all of the perpetrators in our study are far-rightists. Fourth, far-right racists are often stigmatized by mainstream society and many retreat to “free spaces” that allow them to act upon their beliefs away from society’s negative gaze (Simi and Futrell 2010). Such individuals are unlikely to be integrated into a county’s political and social elite or communal life (Beyerlein and Hipp 2005: 995). Finally, we examine county-level variation while Lyons focused on neighborhoods.

We are unable to make a comparison of FRP county residency to the perpetrators of regular homicides county residency because the latter information is unavailable. The FBI’s SHR only includes information on homicide incident location and does not report perpetrator residency location.

We only focused on FRHI that were committed by far-rightists in the contiguous (48 of the 50) US. Due to data limitations and methodological concerns, it is common for criminological research to sample from geographic regions located solely within the contiguous, continental US (Kaminski 2008; Lester 1996; Loftin and Hill 1974; Rosenfeld et al. 2007).

Recent studies have relied on the ECDB to examine the evolution of domestic extremist groups (Freilich et al. 2009), differences between violent and non-violent extremist groups (Chermak et al. 2013), comparisons between far-right homicides and “regular” non-extremist homicides (Gruenewald and Pridemore 2012), fatal far-right attacks against the police (Freilich and Chermak 2009; Suttmoeller et al. 2013) and lone wolf attacks (Gruenewald et al. 2013a, b).

The ECDB’s incident identification and coding is a multi-stage process (Freilich et al 2014). First, open-source publications (e.g. the FBI, GTD, and Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Report) and databases are used to identify cases that could fit the inclusion criteria. Additional incidents are identified in online newspaper articles. After potential incidents are identified, we systematically search more than 30 open-source search engines and databases to collect all publically available information on the homicide events. A coder then reads the documents, verifies that the incident met the inclusion criteria, conducts additional open-source searches, and codes each incident. Variables coded relate to the incident, the offenders, the victims, and the reliability of the open-source documentation. This coding process was iterative and reliability was increased through coder training and multiple coders examining each incident (Freilich et al. 2014).

The vast majority of the FRPs in this study were arrested. However, 14 of the perpetrators were technically not arrested. Six of these perpetrators committed suicide before their arrest, and 5 were killed by law enforcement before they could be arrested. Three others were involved in a prison murder. For all 14 perpetrators the open source information that we collected specifically discussed their linkage to the homicide and described their extremist activities.

The ECDB only includes the FRP’s county of residence at the time of an incident and does not include the length of time the perpetrator resided in the county before engaging in an attack. To assess the likelihood that a FRP lived in the county for at least a year before committing a homicide, and would, therefore, be susceptible to county-level influences (in that they were exposed to the county’s characteristics for an extended period), we randomly selected 20 % of the FRPs (N = 59). We searched these FRPs in the web-engines BeenVerified.com and Ancestry.com to locate information about them. We also reviewed the open-source information collected on these FRPs in the ECDB to see if other sources, such as the media or court documents, specified how long the FRP had resided at the location. No conclusive information was found for 57 % of these FRPs, but we verified the residency for 25 FRPs (43 % of the sample). Twenty-two FRPs (88 %) were determined to live in their county of residency for at least one year prior to the incident, while only 3 FRPs were deemed known transients. Thus, close to 90 % of the FRPs we found information on had resided in the county for at least one year prior to committing a far-right homicide. While some (American) terrorists may engage in conduct to evade capture and take steps (e.g. using aliases) to “stay off the radar” and thus little information exists on their whereabouts (Cothren et al. 2008), FRPs do not fall into this category. The overwhelming number of FRPs in the ECDB was prosecuted for homicides that though they were ideologically motivated were the outcome of (situational) presented opportunities, as opposed to carefully planned strikes.

We also conducted the analysis using the undichotomized variable and the direction and significance are the same as when this measure is used.

We considered calculating the percentage of Jews in each county, but they constitute only about 2 % of the US religious landscape and only 4 % of counties have a Jewish population that exceeds 5 %.

In a separate analysis we looked at the relationship between having any Jews in the county and a county having a Jewish congregation. In 1990 over 62 % of counties that had any Jews also had a congregation, and in 2000 the overlap was 93 %. The results of our multivariate analyses were very similar (significant and in the same direction), regardless of what measure (any Jews present or a Jewish congregation in the county) was used.

The ARDA stores the major source of data on religious groups in America. The Glenmary Research Center is the organization that publishes the data. We contacted them directly to see if they knew of a 1990 county-level measure. They did not think that a reliable measure exists for 1990.

The mainline Protestant groups that were included in both the 1990 and 2000 data collections were: American Baptist Churches in the USA, Christian Church (Disciples of Christ), Congregational Christian Churches, Episcopal Church, Moravian Church in America, National Association of Congregational Christian Churches, Presbyterian Church (USA), Reformed Church in America, United Church of Christ, and United Methodist Church.

The SPLC’s Hate Group Listing places groups into several categories. We combined racist skinheads, skinheads, identity, white nationalists, Ku Klux Klan, Neo-Confederates, and Neo-Nazis in the white hate group count and excluded Black hate groups since FRPs are almost 100 %.White.

The SPLC published both reports annually (since 1994 for militia/patriots and 1990 for hate groups). Although scholars have questioned the SPLC’s procedures (Chermak 2002; Freilich and Pridemore 2006), they have used the same strategies to identify organizations over time (SPLC, 2011).Unlike law enforcement agencies and others that compile intelligence information only on criminally active groups, the SPLC tracks violent and non-violent groups.

There were other variables from the ARDA, US Census, and Uniform Crime Report that we considered including as controls, such as, percentage Evangelical, female headed households, male, African American, white, foreign born, response to the US census, homeowner occupancy rate, unemployment rate, economic inequality index, number of police, per capita police pay, and the ratio of female to male wages. We also considered several GSS variables that were tied to our theoretical concepts. None of these variables contributed to any unique variation in our dependent variables (i.e. no significant effects) or meaningfully changed any of our key findings.

There is a higher number of perpetrator counties than incident counties because multiple perpetrators could have been involved with one incident.

To account for the rarity of the dependent variable, we considered using a procedure suggested by King and Zeng (2001) for generating approximately unbiased and lower-variance estimates of logit coefficients and their variance–covariance matrix. Unfortunately, we could not find a way to use this procedure while also estimating the three models simultaneously, and testing for significant differences in the coefficients across models. Additionally, for the most part the direction of the coefficients and significance levels differed minimally regardless of the modeling technique.

We considered only presenting an analysis for the entire 22 time-period using key predictors from the 1990s. Most of the independent and control variables from 1990 to 2000 are highly correlated at 0.90 and above. However, some characteristics (i.e. divorce rates, 9–11) about the US changed over the 22-year time span.

GeoDa allows one to run regression analysis to investigate this relationship, however to the best of our knowledge the program does not model binary outcome data.

In a separate analysis we found that poverty was significantly and highly (at least 0.66) correlated with a Gini index of economic inequality and the county’s unemployment rate. However, when entered with poverty, these two coefficients were in the opposite direction. Higher levels of unemployment and more economic inequality were associated with greater odds of a FRP. We considered including economic inequality and unemployment in the full analysis, but they were not significant when entered with the remaining variables in the final model. We also considered combining them with poverty to develop an overall measure of deprivation, but the three variables were operating in different directions with the dependent variable.

The mean 1990 income in a county with a FRP was $36,927, and in a county without a FRP it was $29,456. We would have used mean income instead of poverty, but poverty was a more robust indicator and remained significant when other variables were entered.

Other county-level research has found that poverty is associated with increased odds of a terrorist incident occurring in the county (see for e.g. LaFree and Bersani 2014); but these studies examined all terrorist incidents and did not disaggregate to only examine far-right attacks.

References

Agnew R (1992) Foundation for a general strain theory of crime and delinquency. Criminology 30:47–87

Agnew R (1999) A general strain theory of community differences in crime rates. J Res Crime Delinq 36:123–155

Agnew R (2001) Building on the foundation of general strain theory: specifying the types of strain most likely to lead to crime and delinquency. J Res Crime Delinq 38:319–361

Agnew R (2010) A general strain theory of terrorism. Theor Criminol 14(2):131–153

Aho JA (1990) The politics of righteousness: Idaho Christian patriotism. University of Washington Press, Seattle

Akyuz K, Armstrong T (2011) Understanding the sociostructural correlates of terrorism in Turkey. Int Crim Justice Rev 21(2):134–155

Allison PD (2001) Missing data. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Anderson E (2000) Code of the street: decency, violence, and the moral life of the inner city. W. W. Norton, New York

Bakker E (2006) Jihadi terrorists in Europe: their characteristics and the circumstances in which they joined the jihad: an exploratory study. Netherlands Institute of International Relations, Clingendael

Barkun M (1997) Religion and the racist right: the origins of the Christian Identity movement. University of California Press, Berkeley

Bellair PE (1997) Social interaction and community crime: examining the importance of neighbor networks. Criminology 35:677–703

Berrebi C (2009) The economics of terrorism and counterterrorism: What matters and is rational-choice theory helpful? RAND MG-849-OSD. In: Davis PK, Cragin KR (eds) Social science for counterterrorism. RAND Corporation, Santa Monica

Beyerlein K, Hipp JR (2005) Social capital, too much of a good thing? American religious traditions and community crime. Soc Forces 84(2):995–1013

Bjørgo T (1995) Introduction. Terror Polit Viol 7(1):1–16

Blalock HM Jr (1967) Toward a theory of minority-group relations. Wiley, New York

Blazak R (2001) White boys to terrorist men. Am Behav Sci 44(6):982–1000

Blejwas A, Griggs A, Potok M (2005) Terror from the right. SPLC Intell Rep 110:33–46

Broidy L, Agnew R (1997) Gender and crime: a general strain theory perspective. J Res Crime Delinq 34:275–306

Bursik J Jr (1988) Social disorganization and theories of crime and delinquency: problems and prospects. Criminology 26:519–551

Bursik RJ Jr, Grasmick HG (1993) Economic deprivation and neighborhood crime rates, 1960–1980. Law Soc Rev 27(2):263–283

Chermak SM (2002) Searching for a Demon: the media construction of the militia movement. Northeastern University Press, Boston

Chermak SM, Gruenewald J (2015/in press) Laying the foundation for the criminological examination of right-wing, left-wing, and Al Qaeda inspired extremism in the United States. Terror Polit Viol 27(1)

Chermak SM, Freilich JD, Shemtob Z (2009) Law enforcement training and the domestic far-right. Crim Just Behav 36(12):1305–1322

Chermak SM, Freilich JD, Parkin WS, Lynch JP (2012) American terrorism and extremist crime data sources and selectivity bias: an investigation focusing on homicide events committed by far-right extremists. J Quant Criminol 28(1):191–218

Chermak SM, Freilich JD, Suttmoeller M (2013) The organizational dynamics of far-right hate groups in the United States: comparing violent to non-violent organizations. Stud Confl Terror 36(3):193–218

Clarke RV, Newman GR (2006) Outsmarting the terrorists. Praeger, New York

Cothren J, Smith BL, Roberts P, Damphousse KR (2008) Geospatial and temporal patterns of preparatory conduct among American terrorists. Int J Comp Appl Crim Justice 32:23–41

Disha I, Cavendish JC, King RD (2011) Historical events and space of hate: hate crimes against Arabs and Muslims in Post-9/11 America. Soc Prob 58(1):21–46

Dugan L, Young J (2009) Allow extremist participation in the policy-making process. In: Frost NA, Freilich JD, Clear TR (eds) Contemporary issues in criminal justice policy: policy proposals from the american society of criminology conference. Cengage/Wadsworth, Belmont, CA

Dugan L, LaFree G, Piquero AR (2005) Testing a rational choice model of airline hijackings. Criminology 43(4):1031–1070

Durkheim E (1930) Suicide: a study in sociology translated by George Simpson and John A. Spaulding. The Free Press, New York

Ezekiel RS (1995) Inside the racist mind: portraits of american neo-nazis and Klansmen. Penguin, New York

Ferber AL (1998) White man falling: race, gender and white supremacy. Roman and Littlefield, New York

Freilich JD, Chermak SM (2009) Preventing deadly encounters between law enforcement and American far-rightists. Crime Prev Stud 25:141–172

Freilich JD, LaFree G (2015) Criminology theory and terrorism: introduction to the special issue. Terror Polit Viol 27

Freilich JD, Pridemore WA (2006) Mismeasuring militias: limitations of advocacy group data and of state-level studies of paramilitary groups. Justice Q 23:147–162

Freilich JD, Pridemore WA (2007) Politics, culture and political crime: covariates of abortion clinic attacks in the United States. J Crim Justice 35(3):323–336

Freilich JD, Pichardo-Almanzar NA, Rivera CJ (1999) How social movement organizations explicitly and implicitly promote deviant behavior: the case of the militia movement. Justice Q 16(3):655–683

Freilich JD, Chermak SM, Caspi D (2009a) Critical events in the life trajectories of domestic extremist white supremacist groups: a case study analysis of four violent organizations. Criminol Public Policy 8(3):497–530

Freilich JD, Chermak SM, Jr Simone J (2009b) Surveying American State Police Agencies about terrorism threats, terrorism sources, and terrorism definitions. Terror Polit Viol 21(3):450–475

Freilich JD, Chermak SM, Belli R, Gruenewald J, Parkin WS (2014) Introducing the United States extremist crime database (ECDB). Terror Polit Viol 26(2):372–384

Gibson JW (1994) Warrior dreams: violence and manhood in post-Vietnam America. Hill and Wang, New York

Goetz SJ, Rupasingha A, Loveridge S (2012) Social capital, religion, Walmart and hate groups in America. Soc Sci Q 93(2):379–393

Green DP, Strolovich DZ, Wong JS (1998) Defended neighborhoods, integration, and racially motivated crime. Am J Sociol 104(2):372–403

Green DP, Abelson RP, Garnett M (1999) The distinctive political views of hate-crime perpetrators and white supremacists. In: Prentice DA, Miller DT (eds) Cultural divides: understanding and overcoming group conflict. Russell Sage, New York

Gruenewald JA, Pridemore WA (2012) A comparison of ideologically-motivated homicides from the new extremist crime database and homicides from the supplementary homicides reports using multiple imputation by chained equations to hand missing values. J Quant Criminol 28:141–162

Gruenewald JA, Chermak SM, Freilich JD (2013a) Distinguishing “Loner” attacks from other domestic extremist violence: a comparison of far-right homicide incident and offender characteristics. Criminol Public Policy 12(1):65–91

Gruenewald J, Chermak SM, Freilich JD (2013b) Lone wolves and far-right terrorism in the United States. Stud Confl Terror 36(12):1005–1024

Hamm MS (1993) American skinheads: the criminology and control of hate crime. Praeger Publishers, Westport

Hamm MS (2002) In bad company: America’s terrorist underground. Northeastern University Press, Boston

Hamm MS (2007) Terrorism as crime: from the order to Al-Qaeda and beyond. New York University Press, New York

Handler JS (1990) Socioeconomic profile of an American terrorist. Terrorism 13:195–213

Hewitt C (2003) Understanding terrorism in America: from the Klan to Al Qaeda. Routledge, New York

Hirchi T, Gottfredson MR (2001) Self control theory. In: Patternoster R, Bachman R (eds) Explaining criminals and crime. Roxbury, Los Angeles

Jurgensmeyer M (2003) Terror in the mind of god: the global rise of religious violence. University of California Press, Berkeley

Kaminski RJ (2008) Assessing the county-level structural covariates of police homicides. Homicide Stud 12:350–380

Kaplan J (1995) Right wing violence in North America. Terror Polit Viol 7(1):44–95

King RD, Brustein WI (2006) A political threat model of intergroup violence: Jews in Pre-World War II Germany. Criminology 44(4):867–890

King G, Zeng L (2001) Logistic regression in rare events data. Polit Anal 9:137–163

Kornhauser RR (1978) Social sources of delinquency. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Krueger AB (2007) What makes a terrorist: economics and the roots of terrorism. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Krueger AB (2008) What makes a homegrown terrorist? Human capital and participation in domestic Islamic terrorist groups in the U.S.A. Working Paper no. 533 Princeton University Industrial Relations Section: http://www.irs.princeton.edu/pubs/pdfs/533.pdf

LaFree G, Bersani BE (2014) County-level correlates of terrorist attacks in the United States. Criminol Public Policy 13

LaFree G, Dugan L (2009) Research on terrorism and countering terrorism. Crime Justice 38:413–477

LaFree G, Dugan L, Korte R (2009) The impact of British counterterrorist strikes on political violence in Northern Ireland: comparing deterrence and backlash models. Criminology 47(1):17–45

LaFree G, Dugan L, Xie M, Singh P (2012) Spatial and temporal patterns of terrorist attacks by ETA, 1970 to 2007. J Quant Criminol 27:7–29

Lee MR (2000) Community cohesion and violent predatory victimization: a theoretical extension of cross-national opportunity theory. Soc Forces 79:683–706

Lee MR (2008) Civic community in the hinterland: toward a theory of rural social structure and violence. Criminology 46(2):447–477

Lester D (1996) Regional variation in homicide rates of infants and children. Injury Prev 2:121–123

Lipset S, Raab E (1977) The politics of unreason: right wing extremism in America, 1790–1977. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Loftin C, Hill RH (1974) Regional subculture and homicide: an examination of the Gastil–Hackney thesis. Am Sociol Rev 39:714–724

Lyons CJ (2007) Community (dis)organization and racially motivated crime. Am J Sociol 113(3):815–863

McVeigh R (2009) The rise of the Ku Klux Klan: right-wing movements and national politics. University of Michigan Press, Michigan

McVeigh R, Cunningham D (2012) Enduring consequences of right-wing extremism: Klan mobilization and homicides in southern counties. Soc Forces 90(3):843–862

Merton RK (1938) Social structure and anomie. Am Sociol Rev 3:672–682

Messner SF, Rosenfeld R (2007) Crime and the American dream. Thomson/Wadsworth, New York

Nice DC (1988) Abortion clinic bombings as political violence. Am J Polit Sci 32:178–195

Pampel FC (2000) Logistic regression: a primer. Sage, Thousand Oaks

Parkin WS (2012) Developing theoretical propositions of far-right ideological victimization. Ph.D. dissertation, Graduate Center and John Jay College, CUNY

Pridemore WA, Freilich JD (2006) A test of recent subcultural explanations of white violence in the United States. J Crim Justice 34(1):1–16

Putnam RD (1995) Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. J Democr 6(1):65–78

Putnam RD (2000) Bowling alone: the collapse and revival of American community. Simon and Schuster, New York

Rosenfeld R, Messner SF, Baumer EP (2001) Social capital and homicide. Soc Forces 80(1):283–309

Rosenfeld R, Baumer E, Messner SF (2007) Social trust, firearm prevalence, and homicide. Ann Epidemiol 17:119–125

Royston P (2004) Multiple imputation of missing values. Stata J 43:227–241

Sageman M (2004) Understanding terror networks. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia

Sampson RJ (2012) Great American City: Chicago and the enduring neighborhood effect. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Sampson RJ, Bartusch DJ (1998) Legal cynicism and (subcultural?) tolerance of deviance: the neighborhood context of racial differences. Law Soc Rev 32(4):777–804

Sampson RJ, Groves WB (1989) Community structure and crime: testing social disorganization theory. Am J Sociol 94:774–802

Sampson RJ, Raudenbush SW, Earls F (1997) Neighborhoods and violent crime: a multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science 277(5328):918–924

Scheitle C, Adamczyk A (2009) It takes two: the interplay of individual and group theology on social embeddedness. J Sci Study Relig 48:16–29

Shaw CR, McKay HD (1976) Juvenile delinquency and urban areas, 2nd edn. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Shecory M, Laufer A (2008) Social control theory and the connection with ideological offenders among Israeli youth during the Gaza disengagement period. Int J Offender Therapy Comp Criminol 52(4):454–473

Silber MD, Bhatt A (2007) Radicalization in the West: the homegrown threat. New York City Police Department Intelligence Division, New York. Accessed 8 May 2011. http://www.nypdshield.org/public/SiteFiles/documents/NYPD_ReportRadicalization_in_the_West.pdf

Simcha-Fagan O, Schwartz JE (1986) Neighborhood and delinquency: an assessment of contextual effects. Criminology 24(4):667–699

Simi P, Futrell R (2010) American swastika: inside the white power movements hidden spaces of hate. Rowman and Littlefield, New York

Smith BL (1994) Terrorism in America: pipe bombs and pipe dreams. State University of New York Press, New York

Smith BL, Damphousse KR (2009) Patterns of precursor behaviors in the lifespan of an American eco-terrorist group. Criminol Public Policy 8(3):475–496

Smith BL, Morgan KD (1994) Terrorist right and left: empirical issues in profiling American terrorists. Stud Confl Terror 17:39–57

Soule SA, Van Dyke N (1999) Black church arson in the United States, 1989–1996. Ethnic Racial Stud 22:724–742

Stark R (1987) Deviant places: a theory of the ecology of crime. Criminology 25:893–909

Stern J (2003) Terror in the name of god: why religious militants kill. Harper Collins, New York

Sutherland EH, Cressey DR (1978) Criminology, 10th edn. Lippincott, New York

Suttmoeller MJ, Gruenewald J, Chermak SM, Freilich JD (2013) Killed in the line of duty: Comparing police homicides committed by far-right extremists to all police homicides. Law Enforc Exec Forum 13(1):45–64

U.S. Bureau of the Census (1990a) USA counties data file downloads: poverty. http://www.census.gov/support/USACdataDownloads.html#PVY. Accessed 14 Jan 2013

U.S. Bureau of the Census (1990b) USA counties data file downloads: population. http://www.census.gov/support/USACdataDownloads.html#POP. Accessed 14 Jan 2013

U.S. Bureau of the Census (1996) Table 1. Land area, population, and density for states and counties: 1990. http://www.census.gov/population/www/censusdata/files/90den_stco.txt. Accessed 15 Jan 2013

U.S. Bureau of the Census (2000a) USA counties data file downloads: poverty. http://www.census.gov/support/USACdataDownloads.html#PVY. Accessed 14 Jan 2013

U.S. Bureau of the Census (2000c) USA counties data file downloads: population. http://www.census.gov/support/USACdataDownloads.html#POP. Accessed 14 Jan 2013

U.S. Bureau of the Census (2000d) Population, housing units, area, and density: 2000—United States—county by state; and for Puerto Rico census 2000 summary file 1 (SF 1) 100-percent data. http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?pid=DEC_00_SF1_GCTPH1.US05PR&prodType=table. Accessed 21 Jan 2013

U.S. Bureau of the Census (2001) Mapping census 2000: the geography of U.S. diversity. www.census.gov/population/cen2000/atlas/divers.xls. Accessed 24 Jan 2013

Van Buuren S, Boshuizen HC, Knook DL (1999) Multiple imputation of missing blood pressure covariates in survival analysis. Stat Med 18:681–694

Van Dyke N, Soule SA (2002) Structural social change and the mobilizing effect of threat: explaining levels of patriot and militia organizing in the United States. Soc Prob 49:497–520

Wareham J, Cochran JK, Dembo R, Sellers CS (2005) Community, strain and delinquency: a test of a multi-level model of general strain theory. West Criminol Rev 6:117–133

Warner BD (2007) Directly intervene or call the authorities? A study of forms of neighborhood social control within a social disorganization framework. Criminology 45(1):99–128

Webb JJ, Cutter SL (2009) The geography of U.S. terrorist incidents, 1970–2004. Terror Polit Viol 21:428–449

Wilson WJ (1996) When work disappears: the world of the new urban poor. Vintage, New York

Wuthnow R (2004) Saving America? Faith-based services and the future of civil society. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a series of Grants from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) Science and Technology Directorate’s University Program Division; and Resilient Systems Division both directly and through the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START), and a John Jay College Collaborative Research Award. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies, either expressed or implied, of DHS, START, or John Jay College.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Freilich, J.D., Adamczyk, A., Chermak, S.M. et al. Investigating the Applicability of Macro-Level Criminology Theory to Terrorism: A County-Level Analysis. J Quant Criminol 31, 383–411 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9239-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-014-9239-0