Abstract

The two studies reported in the article provide normative measures for 120 novel nominal metaphors, 120 novel similes, 120 literal sentences, and 120 anomalous utterances in Polish (Study 1) and in English (Study 2). The presented set is ideally suited to addressing methodological requirements in research on metaphor processing. The critical (sentence-final) words of each utterance were controlled for in terms of their frequency per million, number of letters and syllables. For each condition in each language, the following variables are reported: cloze probability, meaningfulness, metaphoricity, and familiarity, whose results confirm that the sentences are well-matched. Consequently, the present paper provides materials that can be employed in order to test the new as well as existing theories of metaphor comprehension. The results obtained from the series of normative tests showed the same pattern in both studies, where the comparison structure present in similes (i.e., A is like B) facilitated novel metaphor comprehension, as compared to categorical statements (i.e., A is B). It therefore indicates that comparison mechanisms might be engaged in novel meaning construction irrespectively of language-specific syntactic rules.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

In studies on language processing, the use of well-controlled stimuli is crucial, especially in research employing behavioral or neuroimaging methods, whose results are highly influenced by stimuli characteristics, including, but not limited to, word frequency, meaningfulness, and familiarity (Balota et al. 2006). It is therefore of a great importance to ensure that the stimuli used in such studies have been thoroughly normed for the variables that are important to control for, taking into account the specific research questions that are to be addressed in the experiment proper. Oftentimes, researchers employing quantitative research methods use a shared database of the stimuli that have already been appropriately normed so as to ensure consistency across different projects and laboratories, where the studies are conducted (Campbell and Raney 2016). The present paper provides a database on Polish (Study 1) and English (Study 2) novel nominal metaphors, novel similes, literal, and anomalous sentences that have all been normed on a number of factors in order to ensure that they can effectively be employed in further studies on novel metaphoric and literal language processing.

Metaphoric utterances, such as That lawyer is a shark, are defined as conveying meanings that do not refer to their literal sense (De Grauwe et al. 2010). Consequently, metaphor comprehension is assumed to require the process of cross-domain mapping, in which common features of two concepts (i.e., metaphor source—shark, and metaphor target—lawyer) need to be recognized and structurally aligned (Gibbs and Colston 2012; Bowdle and Gentner 2005). Importantly, as postulated within the Career of Metaphor Model (Bowdle and Gentner 2005), metaphor comprehension is highly modulated by how lexicalized (conventional) a metaphor source is, since a conventional metaphor source, as a result of its repeated use, has both a literal and metaphoric reference. Namely, a conventional metaphor such as That lawyer is a shark involves a source domain (shark) that is polysemous and can denote either a literal (i.e., a predator) or a nonliteral, metaphoric sense (i.e., someone who unscrupulously exploits others; Gentner and Bowdle 2001). This dual reference results in the fact that conventional metaphors might be comprehended as either comparisons or categorizations, with categorization mechanisms being more favorable, as they are faster and less cognitively intensive. In contrast, novel metaphors are not characterized by such a dual reference, as their source domains refer to domain-specific, literal concepts, as a result of which novel metaphoric utterances can be understood only by means of comparison. Consequently, while conventional (familiar) metaphors require meaning retrieval mechanisms, novel (unfamiliar) metaphoric utterances involve the processes of meaning construction that are based on comparison between the source and target domain. A distinction between novel and conventional metaphors, in line with the Career of Metaphor Model (Bowdle and Gentner 2005), is presented in Fig. 1.

Novel and conventional metaphor comprehension according to the Career of Metaphor Model (after Bowdle and Gentner 1999: 92)

The model therefore assumes that novel metaphoric meanings are easier to comprehend when presented as similes (A is like B) compared to nominal (categorical) sentences (A is B), due to the fact that the form of a simile automatically initiates comparison mechanisms that are engaged in novel metaphor processing. Such a hypothesis has previously been supported in a number of behavioral, electrophysiological, and neuroimaging studies (e.g., Bowdle and Gentner 2005; Shibata et al. 2012; Lai and Curran 2013), suggesting that the processing of novel similes is less cognitively taxing compared to novel nominal metaphors.

However, thus far little attention has been devoted to directly comparing novel metaphor comprehension across different languages. Consequently, the question whether the comparison structure facilitates novel meaning comprehension irrespectively of language-specific grammatical properties remains under-investigated. In order to provide valid insights into that notion, it seems crucial to compare languages in which a simile and categorical structure require a syntactically-different realization. For instance, in Polish and English, categorical statements differ in terms of their morpho-syntactic forms (i.e., Polish: A to B; English: A is B). Although in both languages, they include copular clauses, in English, a verbal copula to be needs to be explicitly stated, while in Polish, categorical sentences include a pronominal copula, which is dropped (Bondaruk 2014). On the other hand, using a verbal copula in Polish, which is a highly inflected language, would result in a sentence structure where a verbal copula to be (i.e., A jest B) marks the predicate for instrumental. In contrast, in the case of English categorical statements, a verbal copula to be (i.e., A is B) marks the predicate for nominative. It needs to be noted that since in Polish instrumental is much more structurally complex relative to nominative, metaphor source domains should be embedded in sentences where predicates are marked for nominative by using a pronominal copula (i.e., A to B). The two studies reported in the present article aim to show whether a comparison form present in similes facilitates novel metaphor comprehension in both Polish and English, with Polish nominal statements involving a pronominal copula, and English nominal statements involving a verbal copula.

Importantly, previous research into metaphor comprehension has indicated that, apart from metaphor conventionality, other factors modulating metaphoric meaning processing include the level of predictability, meaningfulness, and metaphoricity of the stimuli (De Grauwe et al. 2010; Jankowiak 2019). All of these variables might be measured by, for instance, employing rating Likert-type scales (Likert 1932), where participants rate utterances by means of selecting an appropriate numerical value on a predetermined scale (Gravetter and Forzano 2012). Likert-type scales have previously been used as a measure in conventionality (familiarity), meaningfulness, and metaphoricity ratings on metaphoric stimuli.

Familiarity is defined as the frequency of encountering an utterance (Gernsbacher 1984; Libben and Titone 2008; Tabossi et al. 2011; Nordmann et al. 2014), and has been shown to highly influence the process of word recognition to the point that it has been referred to as a strong predictor of the speed and accuracy of language processing (Connine et al. 1990; Ellis 2002). In research on metaphor processing, familiarity is understood in terms of meaning conventionality, with higher familiarity ratings for more conventional metaphors (Jankowiak et al. 2017). Additionally, the level of familiarity is interpreted as positively correlated with the subjective frequency of lexical items, as less familiar utterances are less frequently encountered in everyday language.

Next, the level of metaphoricity of an utterance provides answers to the question whether an expression, in order to make sense, needs to be interpreted literally or metaphorically. To this aim, metaphoricity ratings involve participants deciding how metaphorical or literal a given expression is. In studies on metaphor comprehension, metaphoricity ratings are aimed to confirm that novel metaphoric meanings are perceived as more metaphorical than conventional metaphors, both of which are more metaphorical than literal utterances (Arzouan et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2013).

Yet another variable that has been suggested to strongly modulate cognitive mechanisms engaged in metaphor comprehension is the predictability of an utterance (Sperber and Wilson 1986; Frisson and Pickering 2001; Katz and Ferretti 2001). The level of predictability is often tested by means of employing a cloze probability test, whose aim is to examine how much a context sentence suggests a to-be-inferred concept. Consequently, a cloze probability test is employed to investigate if the critical items are embedded in low or highly constraining contexts (Monzó and Calvo 2002). In such a test, participants are provided with utterances which are truncated before the final critical word (e.g., She bought some apples and _______). Respondents are asked to provide the first word that comes to their mind so that the sentence would be meaningful and grammatically correct (Bambini et al. 2013). It has been suggested that the processing of an upcoming lexical item is facilitated when presented in a predictable context compared to a non-predictable one (e.g., Kutas and Hillyard 1984; Zola 1984; Schwanenfluegel and Shoben 1985; Rayner and Pollatsek 1989). In metaphor processing, previous studies have revealed lower predictability for metaphoric than literal utterances, with novel metaphors eliciting lower results in cloze probability tests relative to conventional metaphors (e.g., Coulson and Van Petten 2002; Jankowiak et al. 2017).

All of the aforementioned variables influencing the process of metaphor comprehension have been tested in the two present studies, which were aimed to examine the level of predictability, meaningfulness, familiarity, and metaphoricity of Polish (Study 1) and English (Study 2) novel nominal metaphors, novel similes, literal, and anomalous sentences. By means of controlling the above-mentioned factors, the two studies provide valid insights into whether it is a comparison structure that facilitates novel meaning comprehension in Polish and English. As the two languages differ in the grammatical structures of categorical and comparison sentences, similar patterns of results observed in both Polish and English would indicate that the syntactic structure itself does not modulate complex semantic operations that are engaged in novel metaphor comprehension. Finally, the study aims to provide stimuli to serve as well-controlled materials perfectly suited to further examine a number of other different aspects of novel metaphoric meaning comprehension, and to test competing theories of how novel metaphors are constructed and processed in the human brain.

Study 1: Polish Stimuli

Method

Participants

Participants taking part in the surveys were all Polish native speakers, and were recruited from online social media, research mailing lists, and language forums. Participants spent less than 15 min to complete each survey. Importantly, raters who failed to complete the entire survey were removed from the analyses. Cloze probability tests were completed by 140 participants (Mage = 22.83, SD = 2.52; 123 females), meaningfulness ratings—by 132 participants (Mage = 21.8, SD = 2.4; 115 females), familiarity ratings—by 101 participants (Mage = 22.33, SD = 2.37; 80 females), and metaphoricity ratings—by 102 participants (Mage = 23.32; SD = 2.4, 87 females).

Materials and Design

Materials used in the ratings included 120 novel nominal metaphors (e.g., Blizny to pamiętnik; Eng: Scars are a diary), 120 novel similes (e.g., Blizny są jak pamiętnik; Eng: Scars are like a diary), 120 literal (e.g., Ten egzemplarz to pamiętnik; Eng: This copy is a diary), and 120 anomalous sentences (e.g., Ten młot jest jak pamiętnik; Eng: This hammer is like a diary). Each set shared the same sentence-final word, which was always a concrete noun. Novel nominal metaphors and novel similes shared the same target and source domain, and they differed only in their syntactic structure (i.e., A to B; Eng: A is B vs. A jest jak B; Eng: A is like B). Additionally, the critical words were controlled for in terms of their frequency per million (M = 4.68, SD = .45, range 2.47–4.7), number of syllables (M = 2.34, SD = .48, range 2–3), and number of letters (M = 6.57, SD = 1.45, range 4–11). Frequency values were calculated using the SUBTLEX-PL corpus (Mandera et al. 2014). The mean sentence lengths of the stimuli ranged from 3 to 5; novel nominal metaphors: M = 3.28, SD = .50, novel similes: M = 4.28, SD = .48, literal sentences: M = 4.00, SD = .18, and anomalous sentences: M = 3.71, SD = .57. The list of Polish stimuli is provided in Appendix 1.

Procedure

All of the normative studies were conducted using an online survey-development cloud-based software that enabled designing web-based surveys and collecting survey responses. For the normative tests, the materials were divided into four (meaningfulness ratings) or three (cloze probability tests, familiarity, and metaphoricity ratings) blocks so as to avoid the repetition of the critical word within one block. While meaningfulness ratings included all types of utterances (i.e., novel nominal metaphors, novel similes, literal, and anomalous sentences), normative tests on cloze probability, familiarity, and metaphoricity involved meaningful stimuli only (i.e., novel nominal metaphors, novel similes, and literal utterances).

Participants first gave their consent, after which they were provided with general instructions about the task. In all cases, the instructions were presented together with several examples and explanations. Each participant completed only one block, and rated the presented 120 sentences (in meaningfulness ratings) or 90 sentences (in cloze probability tests, familiarity, and metaphoricity ratings). All of the rating scales included 7-point Likert-type scales, i.e. meaningfulness ratings: 1—totally meaningless, 7—totally meaningful; familiarity ratings: 1—very rarely, 7—very frequently; metaphoricity ratings: 1—very literal, 7—very metaphorical). In cloze probability tests, raters were provided with the beginning of a sentence, and were asked to write a critical word (a noun) which first came to their mind, so that the whole sentence would be meaningful and syntactically correct. The order of stimuli presentation within each survey was randomized and counterbalanced across participants, with an equal number of stimuli per each condition presented to all participants.

For the normative studies with rating scales on stimuli meaningfulness, familiarity, and metaphoricity, analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted, whose results are reported below. Significance values for pairwise comparisons were corrected for multiple comparisons using the Bonferroni correction. If Mauchly’s tests indicated that the assumption of sphericity was violated, the Greenhouse–Geisser correction was applied. In such cases, the original degrees of freedom are reported with the corrected p value.

Results

To determine the reliability of the norming tests, intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated for all dimensions requiring a subjective rating. All measures indicated a high consistency across raters (Table 1).

Cloze probability tests

Cloze probability tests were carried out with a view to ensuring that all of the critical (sentence-final) words were not expected due to the preceding context. Table 2 summarizes the results obtained from the cloze probability tests (reported as the percentage of participants who completed the presented sentence with a critical word) together with familiarity ratings and the correlation between the two variables.

Meaningfulness ratings

To evaluate the meaningfulness of the sentences, raters assessed them on a scale from 1 (totally meaningless) to 7 (totally meaningful). The analysis showed a main effect of utterance type, F(3, 384) = 906.25, p < .001, ε = .774, ηp2 = .876. Pairwise comparisons further revealed that literal sentences (M = 5.66, SE = .07) were rated as more meaningful than novel similes (M = 4.42, SE = .08), p < .001, novel similes were rated as more meaningful than novel nominal metaphors (M = 3.87, SE = .08), p < .001, and novel nominal metaphors were assessed as more meaningful compared to anomalous utterances (M = 1.80, SE = .06), p < .001.

Familiarity ratings

In order to examine the familiarity of the stimuli, raters decided how often they encountered the presented novel nominal metaphors, novel similes, and literal sentences on a scale from 1 (very rarely) to 7 (very frequently). The obtained results revealed a main effect of sentence type, F(2, 196) = 45.94, p < .001, ε = .562, ηp2 = .319. Pairwise comparisons confirmed that novel nominal metaphors (M = 1.80, SE = .09) were less familiar than both novel similes (M = 1.88, SE = .09), p = .014, and literal sentences (M = 2.51, SE = .13), p < .001. Furthermore, novel similes were less familiar than literal utterances, p < .001.

Metaphoricity ratings

In order to assess the metaphoricity of the stimuli, raters decided how metaphorical or literal novel nominal metaphors, novel similes, and literal sentences were on a scale from 1 (very literal) to 7 (very metaphorical). The analysis showed a main effect of sentence type, F(2, 198) = 902.18, p < .001, ε = .658, ηp2 = .901. Pairwise comparisons further showed that novel similes (M = 5.73, SE = .08) were rated as more metaphorical than novel nominal metaphors (M = 5.53, SE = .08), p = .001, as well as than literal sentences (M = 1.86, SE = .07), p < .001. Additionally, novel nominal metaphors were rated as more metaphorical than literal utterances, p < .001. Figure 2 presents meaningfulness, metaphoricity, and familiarity ratings for the materials.

The overall means obtained from the normative tests confirmed desired differences between the conditions. Table 3 provides interscale correlations between stimuli dimensions, and Table 4 presents the summary of stimuli characteristics by sentence type.

Study 2: English Stimuli

Method

Participants

Participants taking part in the web-based surveys were all English native speakers, and were recruited from online social media, research mailing lists, and language forums. Participants spent less than 15 min to complete each survey. Importantly, raters who failed to complete the entire survey were removed from the analyses. Cloze probability tests were completed by 152 participants (Mage = 26.31, SD = 9.99; 78 females), meaningfulness ratings—by 119 participants (Mage = 24.28, SD = 8.03; 62 females), familiarity ratings—by 87 participants (Mage = 26.61, SD = 10.2; 40 females), and metaphoricity ratings—by 87 participants (Mage = 25.96, SD = 9.02; 44 females).

Materials and Design

Materials used in the ratings included 120 novel nominal metaphors (e.g., Viruses are travellers), 120 novel similes (e.g., Viruses are like travellers), 120 literal (e.g., These people are travellers), and 120 anomalous sentences (e.g., Tables are travellers). Similarly to the stimuli tested in Study 1, each set shared the same sentence-final word, which was always a concrete noun. Novel nominal metaphors and novel similes shared the same target and source domain, and they differed only in their syntactic structure (i.e., A is B vs. A is like B). The critical words were controlled for in terms of their frequency per million (M = 3.93, SD = .56, range 2.47–4.95), number of syllables (M = 2.19, SD = .39, range 2–3), and number of letters (M = 6.87, SD = 1.24, range 5–10). Frequency values were calculated using the SUBTLEX-UK corpus (van Heuven et al. 2014). The mean sentence lengths of the stimuli ranged from 3 to 7; novel nominal metaphors: M = 4.12, SD = .82, novel similes: M = 5.12, SD = .83, literal sentences: M = 4.82, SD = .66, and anomalous sentences: M = 4.86, SD = .94. The list of English stimuli is provided in Appendix 2.

Procedure

The procedures applied in the normative tests on English stimuli were the same as those used in Study 1.

Results

To determine the reliability of the norming tests, intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated for all dimensions requiring a subjective rating. All measures indicated high consistency across raters (Table 5).

Cloze Probability Tests

Cloze probability tests were carried out with a view to ensuring that all of the critical (sentence-final) words were not expected due to the preceding context. Table 6 summarizes the results obtained from the cloze probability tests (reported as the percentage of participants who completed the presented sentence with a critical word), together with familiarity ratings and the correlation between the two variables.

Meaningfulness Ratings

To evaluate the meaningfulness of the sentences, raters assessed them on a scale from 1 (totally meaningless) to 7 (totally meaningful). The analysis showed a main effect of utterance type, F(3, 345) = 2026.18, p < .001, ε = .872, ηp2 = .946. Pairwise comparisons further revealed that literal sentences (M = 5.92, SE = .05) were rated as more meaningful than novel similes (M = 4.98, SE = .05), p < .001, novel similes were rated as more meaningful than novel nominal metaphors (M = 4.50, SE = .05), p < .001, and novel nominal metaphors were assessed as more meaningful compared to anomalous utterances (M = 1.85, SE = .05), p < .001.

Familiarity Ratings

In order to examine the familiarity of the stimuli, raters decided how often they encountered the presented novel nominal metaphors, novel similes, and literal sentences on a scale from 1 (very rarely) to 7 (very frequently). The obtained results revealed a main effect of sentence type, F(2, 168) = 159.86, p < .001, ε = .661, ηp2 = .656. Pairwise comparisons confirmed that novel nominal metaphors (M = 2.00, SE = .06) were less familiar than both novel similes (M = 2.13, SE = .07), p < .001, and literal sentences (M = 2.92, SE = .10), p < .001. Furthermore, novel similes were less familiar than literal utterances, p < .001.

Metaphoricity Ratings

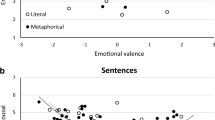

In order to assess the metaphoricity of the stimuli, raters decided how metaphorical or literal novel nominal metaphors, novel similes, and literal sentences were on a scale from 1 (very literal) to 7 (very metaphorical). The analysis showed a main effect of sentence type, F(2, 168) = 2466.83, p < .001, ε = .847, ηp2 = .967. Pairwise comparisons further showed that novel nominal metaphors (M = 5.85, SE = .04) were rated as more metaphorical than novel similes (M = 5.61, SE = .07), p = .001, as well as than literal sentences (M = 1.76, SE = .03), p < .001. Additionally, novel similes were rated as more metaphorical than literal utterances, p < .001. Figure 3 presents meaningfulness, metaphoricity, and familiarity ratings for the materials.

The overall means obtained from the normative tests confirmed desired differences between the conditions. Table 7 provides interscale correlations between stimuli dimensions, and Table 8 presents the summary of stimuli characteristics by sentence type.

Correlation Analyses Between Study 1 and Study 2

The correlation analyses were carried out for Study 1 and Study 2 on the meaningfulness, familiarity, and metaphoricity ratings, and were conducted on averaged values for all novel similes, novel nominal metaphors, literal, and anomalous sentences. The results showed a strong positive correlation between in the two studies on meaningfulness ratings (r(478) = .79, p < .001), familiarity ratings (r(358) = .28, p < .001), and metaphoricity ratings (r(358) = .90, p < .001). Figures 4, 5, and 6 show scatterplots representing the correlations between the two studies on meaningfulness, familiarity, and metaphoricity, respectively.

Discussion and Conclusions

The present article was aimed to provide normative data for a set of Polish (Study 1) and English (Study 2) novel nominal metaphors, novel similes, literal, and anomalous sentences, and to show whether differences in the syntactic structures of the two languages modulate comparison and categorization mechanisms engaged in novel metaphor comprehension.

The obtained results showed that novel similes elicited higher meaningfulness ratings compared to novel nominal metaphors, which is in line with the Career of Metaphor Model (Bowdle and Gentner 2005), and indicates that comparison processes initiated by similes facilitate novel meaning comprehension, and consequently, a form of a simile might ease novel metaphor construction. Under this view, novel metaphoric meanings need to undergo the process of comparison and alignment between the target domain and the literal meaning of the source domain (Bowdle and Gentner 1999; Zharikov and Gentner 2002). Such results are in line with a reaction time (RT) study conducted by Bowdle and Gentner (2005), who observed faster RTs for novel comparisons than novel categorizations, as well as in accordance with an fMRI (functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging) study conducted by Shibata et al. (2012), who found extended brain activation in the right inferior frontal gyrus in response to novel nominal metaphors relative to novel similes.

The observed results might also be interpreted as in line with the Relevance Theory (Sperber and Wilson 1986), which views meaning conventionality as a modulating factor in metaphor vs. simile comprehension, and assumes different explicatures that are communicated by the two types of utterances. Namely, novel creative metaphorical meanings are more likely to be conveyed via similes, which are postulated to require lexically encoded concepts. Conventionalized meanings, in contrast, are usually understood in terms of ad hoc concepts, whose meanings can be implied by typical connotations of metaphor source concept (Carston and Wearing 2011; Jankowiak 2019).

A preference for similes in communicating novel meanings is also in line with the Semantic Space Model (Utsumi 2011), which is based on the Predication Model (Kintsch 2001). In the Semantic Space Model, the meaning of each lexical item takes the form of a semantic space based on word occurrence. Based on this, a semantic similarity between two lexical items can be computed by comparing their respective semantic spaces. In the simulation experiment, Utsumi (2011) showed that categorization processes facilitate conventionalized meaning comprehension, while semantically diverse entities (i.e., novel metaphors) are easier to be interpreted as comparisons.

Importantly, the present results showed the same pattern of results in both Polish and English, therefore indicating that mechanisms involved in novel metaphor processing are similar even in languages with different syntactic rules governing the structure of similes and categorical statements. Thus, though there are differences in the morpho-syntactic forms of Polish and English categorical statements (i.e., Polish: A to B; English: A is B), with a verbal copula to be explicitly stated in English, and a pronominal copula dropped in Polish (Bondaruk 2014), the cognitive mechanisms engaged in arriving at semantically complex, novel metaphoric meanings seem to be irrespective of such language-specific differences. This in turn suggests that mental operations involved in semantic analyses and meaning integration might be superior to syntactic analyses, probably due to extended semantic mechanisms that are required when comprehending unfamiliar, poetic meanings. Further research is, nonetheless, needed in order to examine whether similar patterns of results would be observed in behavioral or electrophysiological studies employing such a between-language design to investigate comparison mechanisms in novel metaphor comprehension.

In addition, meaningfulness ratings for the two studies showed that literal utterances were perceived as most meaningful, followed by novel similes, novel nominal metaphors, and finally anomalous sentences. Importantly, novel metaphors, being very poetic and rarely used in everyday language, still elicited higher meaningfulness ratings as compared to anomalous utterances, thus confirming that the raters were able to arrive at a nonliteral interpretation of novel metaphoric meanings.

The stimuli presented in the present paper have been thoroughly examined in terms of their level of predictability, meaningfulness, familiarity (conventionality), and metaphoricity. Additionally, the critical (final) words of each sentence were selected so that they were all matched on their frequency, concreteness, number of letters and syllables. This is of special importance for any behavioral and electrophysiological research, where dependent variables (e.g., reaction times, event-related brain potentials) are time-locked to the presentation of the sentence-final word. As a result, it is assured that the observed differences in the results elicited in response to different conditions are dependent only on the category of a sentence (i.e., metaphorical, literal, or anomalous), as other lexico-semantic variables influencing language processing were highly controlled for.

Importantly, previous studies on metaphor comprehension have rarely tested stimuli in four separate normative tests (i.e., cloze probability, meaningfulness, metaphoricity, and familiarity), and they most often involved familiarity and/or interpretability ratings, or were limited to controlling only the critical items in terms of their frequency and number of letters. Additionally, previous research has rarely employed 7-point Likert scales, while using such a scale has been proven advantageous, as raters often seem to avoid extreme categories (e.g., 1 or 7), and therefore a scale with fewer than 5 categories would likely provide a too limited number of responses to select from. Furthermore, raters might find it relatively difficult to discriminate between too many categories, and as a result, they could blend the them when provided with more than 9 categories to choose from (Gravetter and Forzano 2012).

The aim of the two present studies was to provide a database of Polish and English novel nominal metaphors, novel similes, literal, and anomalous sentences with variables that have been previously shown to impact the processing of such utterances (i.e., predictability, meaningfulness, familiarity, metaphoricity). The same patterns of results observed in both Polish and English suggest that, although the two languages differ in their grammatical rules to a great extent, the syntactic structures themselves seem not to modulate comparison and categorization mechanisms engaged in novel metaphor comprehension, therefore suggesting that novel simile comprehension is facilitated by a comparison form, irrespectively of language. The large number of items and normed factors influencing language processing that are provided in the two present studies maximize the stimuli flexibility, as they can be effectively employed to suit a number of different research questions, populations, tasks, and designs. The final set of stimuli was selected so that novel similes, novel nominal metaphors, literal, and anomalous sentences are matched for sentence length, meaningfulness, familiarity, metaphoricity, and cloze probability, and the critical words are additionally matched for frequency, number of letters and syllables. The present database will hopefully provide a useful tool to anyone researching the processing and comprehension of metaphoric meanings in Polish and English, in both the monolingual and bilingual populations.

References

Arzouan, Y., Goldstein, A., & Faust, M. (2007). Brainwaves are stethoscopes: ERP correlates of novel metaphor comprehension. Brain Research, 1160, 69–81.

Balota, D. A., Yap, M. M., & Cortese, M. J. (2006). Visual word recognition: The journey from features to meaning (a travel update). In M. Taxler & M. Gernsbacher (Eds.), Handbook of psycholinguistics (2nd ed., pp. 285–375). London: Academic Press.

Bambini, V., Ghio, M., Moro, A., & Schumacher, P. B. (2013). Differentiating among pragmatic uses of words through timed sensicality judgments. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 1–16.

Bondaruk, A. (2014). Characterizing and defining predicational clauses in Polish. In L. Veselovská & M. Janebová (Eds.), Proceedings of the Olomouc Linguistics Colloquium 2014: Language use and language structure (pp. 333–348). Olomouc: Olomouc Modern Languages Series (OMLS).

Bowdle, B. F., & Gentner, D. (1999). Metaphor comprehension: From comparison to categorization. In M. Hahn & S. C. Stoness (Eds.), Proceedings of the twenty-first annual conference of the cognitive science society (pp. 90–95). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Bowdle, B. F., & Gentner, D. (2005). The career of metaphor. Psychological Review, 112(1), 193–216.

Campbell, S. J., & Raney, G. E. (2016). A 25-year replication of Katz et al’.s (1988) metaphor norms. Behavior Research Methods, 48, 330–340.

Carston, R., & Wearing, C. (2011). Metaphor, hyperbole and simile: A pragmatic approach. Language and Cognition, 3(2), 283–312.

Connine, C. M., Mullennix, J., Shernoff, E., & Yelen, J. (1990). Word familiarity and frequency in visual and auditory recognition. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 6, 1084–1096.

Coulson, S., & Van Petten, C. (2002). Conceptual integration and metaphor: An event-related potential study. Memory and Cognition, 30(6), 958–968.

De Grauwe, S., Swain, A., Holcomb, P. J., Ditman, T., & Kuperberg, G. R. (2010). Electrophysiological insights into the processing of nominal metaphors. Neuropsychologia, 48(7), 1965–1984.

Ellis, N. C. (2002). Frequency effects in language acquisition: A review with implications for theories of implicit and explicit language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 24, 143–188.

Frisson, S., & Pickering, M. J. (2001). Obtaining a figurative interpretation of a word: Support for underspecification. Metaphor and Symbol, 16, 149–171.

Gentner, D., & Bowdle, B. F. (2001). Convention, form, and figurative language processing. Metaphor and Symbol, 16(3), 223–247.

Gernsbacher, A. M. (1984). Resolving 20 years of inconsistent interactions between lexical familiarity and orthography, concreteness, and polysemy. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113, 256–281.

Gibbs, R. W., & Colston, H. L. (2012). Interpreting figurative meaning. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Gravetter, F. J., & Forzano, L.-A. B. (2012). Research methods for the behavioral sciences. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Jankowiak, K. (2019). Lexico-semantic processing in bilingual metaphor comprehension: Behavioral and electrophysiological evidence. Poznań: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.

Jankowiak, K., Rataj, K., & Naskręcki, R. (2017). To electrify bilingualism: Electrophysiological insights into bilingual metaphor comprehension. PLoS ONE, 12(4), 1–30.

Katz, A. N., & Ferretti, T. R. (2001). Moment-by-moment reading of proverbs in literal and nonliteral contexts. Metaphor and Symbol, 16, 193–221.

Kintsch, W. (2001). Predication. Cognitive Science, 25(2), 173–202.

Kutas, M., & Hillyard, S. A. (1984). Brain potentials during reading reflect word expectancy and semantic association. Nature, 307, 161–163.

Lai, V. T., & Curran, T. (2013). ERP evidence for conceptual mappings and comparison processes during the comprehension of conventional and novel metaphors. Brain and Language, 127(3), 484–496.

Libben, M. R., & Titone, D. A. (2008). The multidetermined nature of idiom processing. Memory & Cognition, 36, 1103–1121.

Likert, R. (1932). A technique for the measurement of attitudes. Archives of Psychology, 140, 1–55.

Mandera, P., Kueleers, E., Wodniecka, Z., & Brysbaert, M. (2014). SUBTLEX-PL: Subtitle-based word frequency estimates for Polish. Behavior Research Methods, 47(2), 471–483.

Monzó, A. E., & Calvo, M. G. (2002). Context constraints, prior vocabulary knowledge and on-line inferences in reading. Psicothema, 14(2), 357–362.

Nordmann, E., Cleland, A. A., & Bull, R. (2014). Familiarity breeds dissent: Reliability analyses for British-English idioms on measures of familiarity, meaning, literality, and decomposability. Acta Psychologica, 149, 87–95.

Rayner, K., & Pollatsek, A. (1989). The psychology of reading. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Schwanenfluegel, P. J., & Shoben, E. J. (1985). The influence of sentence constraint on the scope of facilitation for upcoming words. Journal of Memory and Language, 24, 232–252.

Shibata, M., Toyomura, A., Motoyama, H., Itoh, H., Kawabata, Y., & Abe, J. (2012). Does simile comprehension differ from metaphor comprehension? A functional MRI study. Brain and Language, 121(3), 254–260.

Sperber, D., & Wilson, D. (1986). Relevance: Communication and cognition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Tabossi, P., Arduino, L., & Fanari, R. (2011). Descriptive norms for 245 Italian idiomatic expressions. Behavior Research Methods, 43, 110–123.

Utsumi, A. (2011). Computational exploration of metaphor comprehension processes using a semantic space model. Cognitive Science, 35(2), 251–296.

Van Heuven, W. J. B., Mandera, P., Kueleers, E., & Brysbaert, M. (2014). Subtlex-UK: A new and improved word frequency database for British English. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 67, 1176–1190.

Yang, F.-P. G., Bradley, K., Huq, M., Wu, D.-L., & Krawczyk, D. C. (2013). Contextual effects on conceptual blending in metaphors: An event-related potential study. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 26(2), 312–326.

Zharikov, S., & Gentner, D. (2002). Why do metaphors seem deeper than similes. In Proceedings of the twenty-fourth annual conference of the cognitive science society (pp. 976–981).

Zola, D. (1984). Redundancy and word perception during reading. Perception and Psycholinguistics, 36, 277–284.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Science Centre, Poland (Grant Number 2017/25/N/HS2/00615).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jankowiak, K. Normative Data for Novel Nominal Metaphors, Novel Similes, Literal, and Anomalous Utterances in Polish and English. J Psycholinguist Res 49, 541–569 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09695-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10936-020-09695-7