Abstract

Purpose

The inclusion of people with mental disorders (MD) into competitive employment has become an important political and therapeutic goal. The present paper investigates meta-analytically to which extent people with MD who were unemployed or on sick leave due to MD prefer to work in a competitive job environment.

Methods

For this systematic review and meta-analysis of proportions, we searched Medline, PsycInfo, Cinahl, Google Scholar, and reference lists for peer-reviewed publications from 1990 to Dec 2023, which provided data on the job preferences of people with MD. Two authors independently conducted full-text screening and quality assessments. Pooled proportions of job preferences were calculated with a random-effects meta-analysis of single proportions, and subgroup analyses were performed to examine characteristics associated with job preferences.

Results

We included 30 studies with a total of 11,029 participants in the meta-analysis. The overall proportion of participants who expressed a preference for competitive employment was 0.61 (95%-CI: 0.53–0.68; I2 = 99%). The subgroup analyses showed different preference proportions between world regions where the studies were conducted (p < 0.01), publication years (p = 0.03), and support settings (p = 0.03).

Conclusion

Most people with MD want to work competitively. More efforts should be given to preventive approaches such as support for job retention. Interventions should be initiated at the beginning of the psychiatric treatment when the motivation to work is still high, and barriers are lower.

Trail Registration

The protocol is published in the Open Science registry at https://osf.io/7dj9r

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Mental disorders (MD) are one of the leading causes of missed educational opportunities, lower educational achievements, sick leave, job loss, long-term unemployment, and social exclusion [1]. However, apart from workplace characteristics such as high demands and low control, which can lead to mental health problems, employment is associated with better health [2]. Unemployment can cause mental distress through loss of structure, social contacts, economic status, activity and other important functions, leading to social exclusion and financial deprivation [3]. For many people with MD, even for those with more prolonged MD or severe mental illness (SMI), employment is an important goal in their recovery process [4,5,6]. Therefore, supporting a return to work is a core priority of mental health care services [7].

People with prolonged MD perceive several barriers to paid employment, including stigma, lack of skills and confidence, and cognitive and motivational problems caused by psychiatric symptoms and the side effects of pharmaceutical treatments [8]. Several vocational rehabilitation services have been established to support people with MD, including SMI, to return to work. Traditional services train individuals in sheltered pre-vocational training or transitional jobs to enable them to work in the general labour market (first train, then place approach). In contrast, Supported Employment (SE), and particularly Individual Placement and Support (IPS), aim to place individuals directly into the general labour market (first place, then train approach), taking the individual’s preferences and needs into account. IPS is more than twice as effective as traditional vocational approaches [9,10,11]. Furthermore, its effectiveness implies that competitive employment is possible even for people with SMI. However, employment rates for people with SMI remain low and are estimated to be less than 30% [1, 12].

People with any form of MD have the same rights to make work-related decisions as all other people do [13]. However, this principle is often not put into practice. It is widely assumed that most people with MD want to work competitively [14, 15]. Nevertheless, preference rates for employment in the general labour market of people with MD still need to be systematically reviewed. This systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the pooled proportion of people who are unemployed or on sick leave due to MD who prefer to work in the general labour market. Knowledge of preference rates for competitive employment enables policymakers and healthcare providers to set realistic goals and priorities to promote the rights of people with MD to work and live an inclusive life.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of peer-reviewed publications reporting preference rates of individuals with MD for competitive employment. We synthesised existing evidence on this topic and assessed contextual factors that may explain differences in preference estimates.

The protocol was published on Dec 5, 2021 (https://osf.io/7dj9r), and the study is reported in adherence to the PRISMA guidelines [16].

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We ran systematic searches on Medline, PsycInfo (both via Ovid) and Cinahl (via EBSCOhost) for peer-reviewed publications from 1990 to Dec 2023. We searched for keywords related to individuals with MD, their preferences, and work (see Supplementary material, Table S1-S2, for the complete search syntax). Additional searches were conducted on Google Scholar and in reference lists of relevant reviews and studies.

Inclusion criteria were peer-reviewed articles of empirical studies providing prevalence data on preferences for competitive employment of individuals with MD aged between 16 and 65 who were unemployed or on sick leave due to MD. Studies published since 1990 and written in Latin letters were included. Studies that did not provide prevalence data on preferences for competitive employment, qualitative studies, and studies that only reported on populations with disabilities other than MD (e.g. mobility, visual, or intellectual disorders) were excluded. Articles not in English or German were translated using DeepL.com to assess their eligibility.

After removing duplicates, two authors (ChA, LE) independently screened the articles based on titles and abstracts, and full-texts were retrieved for closer inspection. Each full-text was independently assessed for eligibility by two authors and blinded to each other’s decisions (ChA, SM). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion involving a third reviewer (DR). If multiple publications were based on the same data, only the first publication was considered in each case.

Data Extraction and Coding

Two authors independently extracted data for each of the included studies (ChA, SM, KS) using a standardised form. Variables extracted for study description were first author, publication year, country, year of study conduction, study design, sampling method, response rate, support setting (vocational rehabilitation, community mental health care setting, inpatient and outpatient psychiatric treatment setting, other settings), gender ratio, age, type and severity of MD, employment status, education, assessment method for job preferences, total sample size, and target sample size.

The outcome of interest was the number of individuals with a preference for competitive employment (including preferences for job training, education, or Supported Employment services) among the target sample. Competitive employment was defined as any full-time or part-time (self-) employment that paid at least the minimum wage or other usual compensation, with or without professional support (including preferences for education, training, or university studies). Non-competitive employment was defined as any employment situation other than competitive employment and included transitional or sheltered employment, employment without pay, or work in day centres. The target sample includes all individuals in the total sample with MD who were unemployed or on sick leave due to MD (e.g. psychiatric inpatients). As recommended in the methodological literature [17], the target sample only included complete cases; subjects with missing answers about job preference were excluded. Because several studies considered different study groups (i.e. subsamples of people with physical impairments or MD), participant characteristics were extracted only when it referred to the subgroup with a majority (> 80%) affected by MD. If a publication only reported on percentages, frequency counts were calculated by the authors. If the preference for competitive employment was reported on a continuum instead of a single value (e.g. strong, moderate, low, no job preference), we extracted the number of individuals with a strong preference. If preferences were reported for different time points (e.g. now, in the near or distant future), we extracted the rate for job preferences in the future.

Study Risk of Bias Assessment

The quality of the studies was independently assessed by two authors (ChA, SM, KS) using seven of the nine items of the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Checklist for Studies Reporting Prevalence Data [18] (Supplementary material, Table S3). Each item (sampling frame, recruitment method, sample size, description of subjects and settings, valid assessment, statistical analysis, and response rate) was rated with yes (1), no (0), or unclear (0), and quality sum scores were computed. A quality sum score of six to seven was classified as good, four to five as moderate, and three or less as poor study quality. The interrater agreement of the quality ratings was 83%. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. We did not perform publication bias tests because their utility in studies reporting proportions is not clear [19].

Data Analysis

We calculated the proportion of individuals with MD who preferred competitive employment for each study. A random-effect analysis of single proportions was performed using the inverse variance method to pool the point estimates of job preferences [20]. The Freeman-Tukey double-arcsine transformation was used while pooling the estimates [21]. Results are reported as forest plots showing the pooled proportions and associated 95% confidence intervals (95%-CI). Heterogeneity between the studies was assessed using I2 and prediction intervals.

Subgroup analyses were performed to explore potential moderating factors that might explain the heterogeneity between proportions across studies. Subgroups were defined during the data extraction process by consensus discussion (ChA, SM, DR), considering knowledge from relevant research. Subgroup analyses were conducted in terms of study quality ratings (high, medium, low), support setting (vocational rehabilitation services, community mental health and other settings, psychiatric treatment settings), the proportion of schizophrenic spectrum disorders in the sample (less than 50%, more than 50%), assessment of job preferences (closed-ended questions asking for preferences to work competitively or to use Supported Employment services, open-ended or multiple choice questions asking for preferences for multiple employment options), study year (before and after the financial crisis in 2008), and world regions of studies (America, Europe, Australia, and Asia). Differences between subgroups were tested using Chi2 tests with α = 0.05.

By JBI recommendations [22], we did not exclude low-quality studies from the meta-analysis. Instead, we performed sensitivity analyses 1) by excluding the low-quality studies to explore their contribution to the results of the meta-analysis and subgroup comparisons and 2) by excluding studies with inadequate recruitment methods (JBI Q2).

All statistical analyses were conducted using meta (version 6.2-1) [23] of the R statistical software (version 4.2.2) [24].

Results

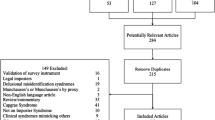

After removing duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of 2754 unique database records for eligibility (Fig. 1). We reviewed 131 full-text articles from the database search and 40 from the searches in the reference lists and Google Scholar. Of these, 30 studies were identified as eligible and were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis [14, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53].

The studies included 16,062 individuals with sample sizes ranging from 35 to 3380 for single studies (Table 1). The size of the target samples ranged from 16 to 2163 individuals, summing up to a total of 11,029 participants included in the meta-analysis.

Twelve studies were conducted in the United States, four in Germany, three in the United Kingdom, Australia, and India, two in Belgium, and one in Italy, Norway, and Switzerland. Studies were published between 1992 and 2021, with 13 studies published before 2008 (1992 to 2007) and 17 published after 2008 (2011 to 2021).

The studies included between 1.3% and 72.2% female participants, and mean age ranged from 24.3 to 51.4 years. Several clinical and social sample characteristics were not or only incompletely reported. For example, the reported MD varied from “history of mental illness” [26] over “mental or emotional problems” [37] and “homeless individuals with severe and persistent mental illness “ [28] to the number or proportion of specific diagnoses in the sample. Of the studies that reported diagnostic information, twelve included fewer than 50% with a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, and ten included more than 50%.

Six studies were conducted in a vocational rehabilitation setting, ten in community mental health settings, four studies were conducted in “other” settings (normal population, self-help programmes), and ten studies were conducted in inpatient and outpatient psychiatric treatment settings. Two vocational settings aimed to reintegrate their service users into competitive employment (Supported Employment settings) [34, 44], and four targeted unspecific or sheltered employment [30, 31, 49, 53].

Job preferences were assessed using a variety of methods. Most studies (n = 15) used a single closed-ended question asking participants whether they wished to work in a competitive job or asking them about the intensity of their job preference. Some asked for job preferences within a particular time frame, while most asked about job preferences without a time reference. Three studies asked about the wish to use a Supported Employment service to attain a regular job. Other studies asked for vocational preferences using open-ended questions (n = 5) or a list of multiple vocational options (multiple choice; n = 5) [14, 42, 49, 50, 53]. Open-ended questions asked participants about their vocational aspirations [28], goals relevant to their participation in the vocational rehabilitation support programme [30], what they hope to accomplish as a result of their mental health treatment [39], what they hope to do, change, or accomplish in the next year [43], and what they would like to see changed with regard to their finances [52]. Multiple-choice questions asked participants to identify preferred vocational goals out of a list with multiple vocational options like competitive employment, self-employment, education and training, freelance work, sheltered employment or vocational rehabilitation, day activity centres, voluntary work, domestic work, and no vocational activity. Two studies did not describe the assessment method [32, 47]. These studies were categorised into the first assessment subgroup (closed-ended questions) based on their description of the findings.

Study quality ratings ranged from 3 to 7 out of 7 possible scores (Table 1 and Supplementary material, Table S4). Our assessment classified the quality of seven studies as high, 18 as medium, and five as low. Overall, study quality was low regarding recruitment procedure and sample size (Supplementary material, Table S4). Study quality was high regarding the sampling frame, description of subjects and settings, assessment methods, and statistical analysis.

Single preference rates in the individual studies ranged between 17.7 and 92.2%. The meta-analysis revealed a pooled proportion of 0.61 individuals who prefer competitive employment (95%-CI 0.53 to 0.68; Fig. 2). Study heterogeneity was substantial; the overall I2 statistic for heterogeneity was 99%, and the prediction interval ranged from 0.21 to 0.94.

Figure 3 shows the subgroup comparisons. Details are presented in Supplementary material, Fig. S1-S6. The subgroup analyses comparing study quality ratings, the proportion of people with schizophrenic disorders, and the assessment methods revealed no significant differences. Subgroups significantly differed regarding the support settings, publication years, and the world regions where the studies had been conducted.

Subgroup analyses of pooled proportions of people with mental disorders who prefer competitive employment (The forest plots of subgroup analyses showing the individual studies and their subgroup assignments are shown in the Supplementary material, Fig. S1-S6. JBI = Joanna Briggs Institute, NA = not available)

Preference proportions from studies that were conducted in Australia and Asia were higher (0.77; 95%-CI 0.67 to 0.85; I2 = 57% and 0.83; 95%-CI 0.71 to 0.92; I2 = 83% respectively) than those conducted in America (0.61; 95%-CI 0.51 to 0.70; I2 = 97%) or Europe (0.49; 95%-CI 0.38 to 0.61; I2 = 98%). Regarding support settings, preference proportions were highest in psychiatric treatment settings (0.71; 95%-CI 0.61 to 0.80; I2 = 92%), followed by community mental health and other settings (0.59; 95%-CI 0.49 to 0.68; I2 = 99%). Vocational rehabilitation settings showed the lowest preference proportion (0.46; 95%-CI 0.29 to 0.64; I2 = 98%). Among the vocational rehabilitation settings, the Supported Employment settings targeting competitive employment [34, 44] show preference proportions higher than the overall proportion, while the vocational rehabilitation settings targeting unspecific or sheltered employment [30, 31, 49, 53] show preference proportions lower than the overall preference proportion (Supplementary material, Fig. S2). Studies published before 2008 reported smaller preference proportions (0.52; 95%-CI 0.44 to 0.61; I2 = 97%) than studies published after 2008 (0.67; 95%-CI 0.56 to 0.76; I2 = 99%). Regarding assessment methods, there is a trend (p = 0.13) for larger preference proportions if assessed with closed-ended questions asking participants whether they wanted to work or wished access to Supported Employment services (0.64; 95%-CI 0.55 to 0.73; I2 = 99%). Preference proportions were smaller when job preferences were indirectly assessed using open-ended or multiple-choice questions (0.53; 95%-CI 0.43 to 0.63; I2 = 92%).

The sensitivity analyses (Supplementary material, Fig. S7-S8) showed no difference in the pooled proportion of job preferences after excluding low-quality studies (0.59; 95%-CI 0.51 to 0.67; I2 = 99%; k = 25) or studies with inadequate recruitment methods (0.61; 95%-CI 0.42 to 0.78; I2 = 100%; k = 9).

Discussion

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of proportions among 30 studies that asked individuals with MD who were unemployed or on sick leave due to MD about their preference for competitive employment. This is the first study that systematically synthesises reported preference proportions into a meta-analysis. The pooled analysis showed that 61% of study participants prefer to work competitively. The subgroup analyses showed that the preference proportion varies according to the support setting, world region, and publication year. These findings suggest that preferences are not static but dynamic and malleable, influenced by socio-cultural and economic factors.

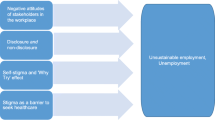

The differences we found between the world regions suggest that socio-economic and cultural factors may influence individuals' job preferences. Socio-economic factors such as lower economic development, unequal income distributions, or weak unemployment protection further reinforce the adverse effects of unemployment on mental health [3]. Thus, it is conceivable that these factors also increase preferences for competitive employment. In contrast, fear of losing social security benefits was a significant barrier to employment in more developed countries and increased the likelihood of preferring non-employment [30, 45, 50, 51]. This may explain the lower preference proportion that we found in the European and American studies. Good unemployment and social security insurance guarantees during the job resumption process could support people with MD in pursuing their preferences for a competitive job. In terms of cultural factors, it is known that Asian cultures promote specific work ethics, which may explain some of the differences [54].

In our study, the job preference prevalence was higher in inpatient and outpatient psychiatric treatment settings than in vocational rehabilitation services. This may be related to the fact that more people in psychiatric treatment settings are on sick leave, while most people in vocational rehabilitation settings are unemployed. The barriers to maintaining employment and returning to work after sick leave are lower than for reintegration into new employment [55]. In addition, service users’ preferences for competitive employment were in line with the effectiveness of their vocational rehabilitation services. While Supported Employment services consistently showed to be more effective than traditional pre-vocational services [9,10,11], preferences for competitive employment were apparently higher in the Supported Employment studies [34, 44] than in those studies whose vocational rehabilitation service targeted unspecific or sheltered employment [30, 31, 49, 53]. This also may be related to the long time spent in psychiatric rehabilitation, which seems to make people with MD fear re-employment and resign themselves to their situation [31, 36, 38]. Therefore, vocational support efforts should begin as early as possible in the mental health recovery process, when their motivation to work is still high, and barriers to work are smaller. For example, workplace interventions combined with therapeutic interventions showed good effectiveness for people on sick leave due to MD [56, 57], and Supported Education programmes could be an appropriate intervention to support young people with MD [58].

With the duration of the mental disorder, the risk for social exclusion increases regarding work and other areas of life. Prolonged and frequent psychiatric hospitalisations are significantly associated with social exclusion regarding employment, housing, family situations, and decreased friendship contacts [59]. The more life domains are affected by social exclusion, the more likely work becomes just one priority among many others. This may also be reflected in our study's different preference proportions across assessment methods. Preferences for competitive employment were higher when asked directly with closed-ended questions than when assessed by open-ended or multiple-choice questions. This finding may suggest that people with MD indeed prefer being included in competitive employment. However, if different goals or support needs compete, people with MD must prioritise.

This study has some limitations. The included studies showed considerable heterogeneity in the reported preference proportions, study quality, support settings, mental disorders, and assessment methods. The wide prediction interval in job preference proportions may comprise the interpretation and may limit our findings’ generalisability. Secondly, only few of the included studies were rated as high-methodology papers. In most studies, the quality was rated low regarding recruitment methods and sample sizes, which may have led to biased estimates and low precision. More high-quality research on the job preferences of people with MD is needed to clarify the influence of methodological heterogeneity on the estimated preference proportion. Thirdly, findings from subgroup analyses should be considered exploratory and hypothesis-generating.

The results of this study show that most individuals with MD want to work competitively. However, to date, less than 30% of them are included in the general labour market [1, 12]. Considering the UN Convention on the Rights of People with Disabilities [13], this gap implies the need for more effective vocational support, such as Supported Employment services. Vocational interventions should be offered in different settings and initiated early in mental health treatment and care when the motivation to work is still high, and barriers to re-employment are lower. The greater the barriers to work have become for people with MD (e.g. through delayed work integration assistance after having already lost employment or through longer treatment paths following the first train, then place approach) [9,10,11, 55, 59], the more their motivation may be downregulated, which may result in subsequent social exclusion. To support people with MD in realising their right to work and social inclusion, we need to incentivise rather than sanction the return to work (e.g. through loss of social security insurance) and focus on job retention besides reintegration into the general labour market.

Data Availability

The authors confirm that all data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article. The R code of the meta-analysis can be accessed upon request at the corresponding author.

References

Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development OECD. Sick on the job? Myths and realities about mental health and work. Paris, France: OECD Publishing; 2012.

Harvey SB, Sellahewa DA, Wang MJ, Milligan-Saville J, Bryan BT, Henderson M, et al. The role of job strain in understanding midlife common mental disorder: a national birth cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(6):498–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(18)30137-8.

Paul KI, Moser K. Unemployment impairs mental health: meta-analyses. J Vocat Behav. 2009;74(3):264–282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.01.001.

Axiotidou M, Papakonstantinou D. The meaning of work for people with severe mental illness: a systematic review. Ment Health Rev J. 2021;26(2):170–179. https://doi.org/10.1108/MHRJ-12-2020-0088.

O’Day B, Kleinman R, Fischer B, Morris E, Blyler C. Preventing unemployment and disability benefit receipt among people with mental illness: evidence review and policy significance. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2017;40(2):123. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000253.

Lloyd C, Waghorn G. The importance of vocation in recovery for young people with psychiatric disabilities. Br J Occup Ther. 2007;70(2):50–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/030802260707000202.

World Health Organization WHO. Guidance on community mental health services: promoting person-centred and rights-based approaches. 2021.

Blank A, Harries P, Reynolds F. Mental health service users’ perspectives of work: a review of the literature. Br J Occup Ther. 2011;74(4):191–199. https://doi.org/10.4276/030802211X13021048723336.

Modini M, Tan L, Brinchmann B, Wang M-J, Killackey E, Glozier N, et al. Supported employment for people with severe mental illness: systematic review and meta-analysis of the international evidence. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(1):14–22. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.115.165092.

Richter D, Hoffmann H. Effectiveness of supported employment in non-trial routine implementation: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2019;54(5):525–531. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-018-1577-z.

Suijkerbuijk YB, Schaafsma FG, van Mechelen JC, Ojajärvi A, Corbiere M, Anema JR. Interventions for obtaining and maintaining employment in adults with severe mental illness, a network meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:CD011867. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011867.pub2.

Richter D, Hoffmann H. Social exclusion of people with severe mental illness in Switzerland: results from the Swiss Health Survey. Epidemiol Psychiatr Sci. 2019;28(4):427–435. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796017000786.

United Nations: Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://www.ohchr.org/en/instruments-mechanisms/instruments/convention-rights-persons-disabilities (2006). Accessed 07.04.2022.

Westcott C, Waghorn G, McLean D, Statham D, Mowry B. Interest in employment among people with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiat Rehabil. 2015;18(2):187–207. https://doi.org/10.1080/15487768.2014.954162.

Bond GR, Drake RE. Making the case for IPS supported employment. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2014;41:69–73. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-012-0444-6.

Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int J Surg. 2021;88: 105906. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijsu.2021.105906.

Akl EA, Kahale LA, Agoritsas T, Brignardello-Petersen R, Busse JW, Carrasco-Labra A, et al. Handling trial participants with missing outcome data when conducting a meta-analysis: A systematic survey of proposed approaches. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0083-6.

Munn Z, Moola S, Lisy K, Riitano D, Tufanaru C. Methodological guidance for systematic reviews of observational epidemiological studies reporting prevalence and incidence data. Int J Evid Based Healthc. 2015;13(3):147–153. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000054.

Barker TH, Migliavaca CB, Stein C, Colpani V, Falavigna M, Aromataris E, et al. Conducting proportional meta-analysis in different types of systematic reviews: A guide for synthesisers of evidence. BMC Medical Res Methodol. 2021;21(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-021-01381-z.

Schwarzer G, Rücker G. Meta-Analysis of Proportions. In: Evangelou E, Veroniki AA, editors. Meta-Research: methods and Protocols. Springer, US: New York, NY; 2022. p. 159–172.

Freeman MF, Tukey JW. Transformations related to the angular and the square root. Ann Math Stat. 1950;21(4):607–611. https://doi.org/10.1214/aoms/1177729756.

Lisy K. Quality counts: Reporting appraisal and risk of bias. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2015;13(3):1–2. https://doi.org/10.11124/jbisrir-2015-2267.

Balduzzi S, Rücker G, Schwarzer G. How to perform a meta-analysis with R: a practical tutorial. BMJ Mental Health. 2019;22(4):153–160. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2019-300117.

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. In: Computing RFfS, editor. R version 4.0.3 ed. R Core Team: Vienna, Austria; 2020.

Ali M, Schur L, Blanck P. What types of jobs do people with disabilities want? J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21:199–210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-010-9266-0.

Bonsaksen T, Fouad M, Skarpaas L, Nordli H, Fekete O, Stimo T. Characteristics of Norwegian clubhouse members and factors associated with their participation in work and education. Br J Occup Ther. 2016;79(11):669–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022616639977.

Briest J. Health condition, health care utilisation and attitude towards return to work in individuals receiving temporary disability pension. Gesundheitswesen. 2020;82(10):794–800. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0795-3511.

Camardese MB, Youngman D. HOPE: Education, employment, and people who are homeless and mentally ill. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 1996;19(4):45–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0095423.

Casper ES, Carloni C. Assessing the underutilization of supported employment services. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2007;30(3):182–188. https://doi.org/10.2975/30.3.2007.182.188.

Drebing CE, Van Ormer EA, Schutt RK, Krebs C, Losardo M, Boyd C, et al. Client goals for participating in VHA vocational rehabilitation: distribution and relationship to outcome. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2004;47(3):162–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/00343552040470030501.

Eikelmann B, Reker T. A second labour market? Vocational rehabilitation and work integration of chronically mentally ill people in Germany. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;88(2):124–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03425.x.

Filia K, Cotton S, Watson A, Jayasinghe A, Kerr M, Fitzgerald P. Understanding the barriers and facilitators to employment for people with bipolar disorder. Psychiatr Q. 2021;92(4):1565–1579. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-021-09931-w.

Frounfelker RL, Wilkniss SM, Bond GR, Devitt TS, Drake RE. Enrollment in supported employment services for clients with a co-occurring disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(5):545–547. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.62.5.pss6205_0545.

Graffam JH, Naccarella L. Disposition toward employment and perspectives on the employment process held by clients with psychiatric disabilities. Aust Disabil Rev. 1997;3:3–15.

Gühne U, Pabst A, Lobner M, Breilmann J, Hasan A, Falkai P, et al. Employment status and desire for work in severe mental illness: results from an observational, cross-sectional study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56(9):1657–1667. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02088-8.

Hatfield B, Huxley P, Mohamad H. Accommodation and employment: A survey into the circumstances and expressed needs of users of mental health services in a Northern Town. Br J Soc Work. 1992;22(1):61–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.bjsw.a055831.

Henry AD, Hooven F, Hashemi L, Banks S, Clark R, Himmelstein J. Disabling conditions and work outcomes among enrollees in a Medicaid buy-in program. J Vocat Rehabil. 2006;25(2):107–117.

Hölzle P, Baumbach A, Mernyi L, Hamann J. Return to work: a psychoeducational module—An intervention study. Psychiatr Prax. 2018;45(6):299–306. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-105775.

Iyer SN, Mangala R, Anitha J, Thara R, Malla AK. An examination of patient-identified goals for treatment in a first-episode programme in Chennai India. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2011;5(4):360–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-7893.2011.00289.x.

Khare C, Mueser KT, Fulford D, Watve VG, Karandikar NJ, Khare S, et al. Employment functioning in people with severe mental illnesses living in urban vs rural areas in India. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55(12):1593–1606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01901-0.

Khare C, Mueser KT, Bahaley M, Vax S, McGurk SR. Employment in people with severe mental illnesses receiving public sector psychiatric services in India. Psychiatry Res. 2021;296:113673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113673.

Knaeps J, Neyens I, van Weeghel J, Van Audenhove C. Perspectives of hospitalized patients with mental disorders and their clinicians on vocational goals, barriers, and steps to overcome barriers. J Ment Health. 2015;24(4):196–201. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2015.1036972.

Laudet AB, Magura S, Vogel HS, Knight EL. Interest in and obstacles to pursuing work among unemployed dually diagnosed individuals. Subst Use Misuse. 2002;37(2):145–170. https://doi.org/10.1081/JA-120001975.

Macias C, DeCarlo LT, Wang Q, Frey J, Barreira P. Work interest as a predictor of competitive employment: policy implications for psychiatric rehabilitation. Admin Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. 2001;28(4):279–297. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1011185513720.

McQuilken M, Zahniser JH, Novak J, Starks RD, Olmos A, Bond GR. The work project survey: consumer perspectives on work. J Vocat Rehabil. 2003;18(1):59–68.

Mueser KT, Salyers MP, Mueser PR. A prospective analysis of work in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2001;27(2):281–296. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a006874.

Poremski D, Distasio J, Hwang SW, Latimer E. Employment and income of people who experience mental illness and homelessness in a large Canadian sample. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(9):379–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674371506000902.

Ramsay CE, Broussard B, Goulding SM, Cristofaro S, Hall D, Kaslow NJ, et al. Life and treatment goals of individuals hospitalized for first-episode nonaffective psychosis. Psychiatry Res. 2011;189(3):344–348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.05.039.

Rennhack F, Lindahl-Jacobsen LE, Schori D. Pre-vocational therapy in mental health. Clients’ desired and achieved productivity status. Scand J Occup Ther. 2021;30(2):195–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/11038128.2021.1968950.

Secker J, Bob G, Seebohm P. Challenging barriers to employment, training and education for mental health service users: the service user’s perspective. J Mental Health. 2001;10(4):395–404. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230123559.

Secker J, Gelling L. Still dreaming: Service users’ employment, education and training goals. J Ment Health. 2006;15(1):103–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230500512508.

Serowik KL, Rowe M, Black AC, Ablondi K, Fiszdon J, Wilber C, et al. Financial motivation to work among people with psychiatric disorders. J Ment Health. 2014;23(4):186–190. https://doi.org/10.3109/09638237.2014.924046.

Zaniboni S, Fraccaroli F, Villotti P, Corbiere M. Working plans of people with mental disorders employed in Italian social enterprises. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2011;35(1):55–58. https://doi.org/10.2975/35.1.2011.55.58.

Kim AE, Park G-S. Nationalism, Confucianism, work ethic and industrialization in South Korea. J Contemporary Asia. 2003;33(1):37–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472330380000041.

Zürcher SJ, Zürcher M, Burkhalter M, Richter D. Job retention and reintegration in people with mental health problems: a descriptive evaluation of supported employment routine programs. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2023;50(1):128–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-022-01227-w.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Verbeek JH, Neumeyer-Gromen A, Verhoeven AC, Bültmann U, Faber B. Interventions to improve return to work in depressed people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006237.pub4.

Joyce S, Modini M, Christensen H, Mykletun A, Bryant R, Mitchell PB, et al. Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic meta-review. Psychol Med. 2016;46(4):683–697. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715002408.

Bond GR, Al-Abdulmunem M, Marbacher J, Christensen TN, Sveinsdottir V, Drake RE. A systematic review and meta-analysis of IPS supported employment for young adults with mental health conditions. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2023;50(1):160–172. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-022-01228-9.

Smith P, Nicaise P, Giacco D, Bird VJ, Bauer M, Ruggeri M, et al. Use of psychiatric hospitals and social integration of patients with psychiatric disorders: a prospective cohort study in five European countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55:1425–1438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-020-01881-1.

Acknowledgements

We thank Laila Elhilali for her excellent support during the search and screening process.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Universitäre Psychiatrische Dienste Bern. The authors declare that no funds, grants, or other support were received during the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Christine Adamus, Dirk Richter, and Simeon Joel Zürcher contributed to the study conception and design. The literature search, data collection, and the selection process were conducted by Christine Adamus, Sonja Mötteli, and Dirk Richter. Data extraction, summarisation, and analysis were performed by Christine Adamus, Sonja Mötteli, Dirk Richter, and Kim Sutor and all authors contributed to the data interpretation. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Christine Adamus and Sonja Mötteli and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Adamus, C., Richter, D., Sutor, K. et al. Preference for Competitive Employment in People with Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Proportions. J Occup Rehabil (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-024-10192-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-024-10192-0