Abstract

Purpose

A comprehensive review of the literature on the time between the onset of symptoms and the first episode of care and its effects on important worker outcomes in compensated musculoskeletal conditions is currently lacking. This scoping review aimed to summarize the factors associated with time to service and describe outcomes in workers with workers’ compensation accepted claims for musculoskeletal conditions.

Methods

We used the JBI guidelines for scoping reviews and reported following the PRISMA-ScR protocol. We included peer-reviewed articles published in English that measured the timing of health service initiation. We conducted searches in six databases, including Medline (Ovid), Embase (Ovid), PsycINFO, Cinahl Plus (EBSCOhost), Scopus, and the Web of Science. Peer-reviewed articles published up to November 01, 2022 were included. The evidence was summarized using a narrative synthesis.

Results

Out of the 3502 studies identified, 31 were included. Eight studies reported the factors associated with time to service. Male workers, availability of return to work programmes, physically demanding occupations, and greater injury severity were associated with a shorter time to service, whereas female workers, a high number of employees in the workplace, and having legal representation were associated with a longer time to service. The relationship between time service and worker outcomes was observed in 25 studies, with early access to physical therapy and biopsychosocial interventions indicating favourable outcomes. Conversely, early opioids, and MRI in the absence of severe underlying conditions were associated with a longer duration of disability, higher claim costs, and increased healthcare utilization.

Conclusion

Existing evidence suggests that the time to service for individuals with compensated musculoskeletal conditions was found to be associated with several characteristics. The relationship between time to service and worker outcomes was consistently indicated in the majority of the studies. This review highlights the need to consider patient-centred treatments and develop strategies to decrease early services with negative effects and increase access to early services with better outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Work-related musculoskeletal conditions are a major cause of work disability worldwide [1]. These conditions constitute a considerable proportion of workers’ compensation claims [2,3,4]. In Canada and Australia, an estimated 1.2 million claims involving time off work were compensated for musculoskeletal conditions between 2004 and 2013 [5]. In Australia, injury and musculoskeletal conditions contributed to 87% of all workers’ compensation claims in 2020–2021 [6]. Despite a decreasing trend in total claim rates, work disability (i.e. absence from work due to injury/illness) and related compensation costs for musculoskeletal conditions remain a significant problem in high-income countries. For example, total workers’ compensation costs in Australia have increased 30% since 2016–2017 to $10.8 billion in 2020–2021 [4, 7]. In 2021–2022, musculoskeletal conditions represented approximately 7.3 million cases of time loss from work in Great Britain [8]. Most workers’ compensation schemes fund healthcare services to support injured workers’ return to work and recovery trajectories [9,10,11].

The timing of healthcare service is a key quality indicator for process measures within workers’ compensation systems [12] and has previously been associated with outcomes for workers with claims for musculoskeletal conditions [13, 14]. For example, several studies have demonstrated that delay in appropriate health services is associated with a longer period of absence from work (i.e. extended duration of disability), poorer rates of return to work, and worse recovery outcomes for musculoskeletal conditions, such as low back pain [15,16,17,18,19]. A recent cohort study on the timing of physical therapy among individuals with knee osteoarthritis demonstrates that a delay in initiating physical therapy of more than one month is associated with an increased risk of future opioid utilization compared to initiating physical therapy within one month (i.e. early) of the index date [20].

Timely access to appropriate healthcare services can expedite injury recovery and facilitate a quicker return to work [21,22,23]. Findings from a randomized controlled trial study reveal that early intervention, involving thorough examinations, information, and recommendations to stay active for patients with acute low back conditions, resulted in a significantly higher return to work rate at 12-month follow-up (i.e. 68.4% of the patients in the intervention group returned to work compared to 56.4% in the control group) [24]. Moreover, a systematic review of physical therapy (PT) studies by Ojha and Colleagues found that early PT, compared to delayed PT, was associated with lower costs and reduced subsequent health service utilization [25]. However, it is important to note that early treatment with some services with limited evidence to support, such as opioids and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for some musculoskeletal conditions (e.g. acute nonspecific low back condition), is not always useful and can result in increased healthcare costs and utilization [26]. A recent systematic review and narrative analysis showed that undergoing early MRI (i.e. MRI within the first 4 to 6 weeks of the index visit) compared to no MRI for low back pain without severe underlying conditions is associated with a longer disability duration [27]. Moreover, another systematic review discovered that prescribing opioids within the first 12 weeks (early) of the onset of musculoskeletal conditions is associated with prolonged work disability among workers’ compensation claims [28].

Access to timely and appropriate healthcare services within the workers’ compensation system can be influenced by various factors. Individual characteristics (e.g. age and gender), injury severity, occupation, and provider type have been previously reported as the factors that can affect the timing of health service utilization [29]. Furthermore, factors related to insurance policies (e.g. waiting periods for assessment, financial incentives, limiting provider choice in some jurisdictions), healthcare-related factors (e.g. health providers’ unwillingness to treat patients receiving workers’ compensation), work-related factors (e.g. work-relatedness of the injury), and access challenges (e.g. remoteness) have been shown to influence the time to service [15, 18, 22, 29,30,31,32]. A study conducted by Kominski and Colleagues revealed that policies that limit healthcare utilization may have a negative impact on access to quality care, return to work rates, and recovery outcomes [15]. In the United States, for example, due to limited first-line provider choice, 13.3% of workers encountered “some or a lot of difficulty getting medical care” when they were first injured [33]. Similarly, a study in California found that 8.5% of workers faced challenges in accessing physical therapists, 7.9% “specialist care”, or 2.5% “prescription medications” [15]. While several reviews have been conducted in the general population [34, 35], there is a lack of evidence regarding a comprehensive review of health service timing and the factors influencing the timing of health services for musculoskeletal conditions within the context of workers’ compensation systems exclusively.

Given the pervasive nature of musculoskeletal conditions and the corresponding WC claims, it is paramount to systematically map the available literature regarding the factors that influence compensation outcomes and the relationship between time-to-service and those outcomes. Empirical data on the timing of health service differ in terms of musculoskeletal conditions, types of services, and the outcome measures involved, and aggregating findings of multiple studies is impractical [27, 28, 36]. As a result, we conducted a scoping review to provide a literature summary of the factors influencing time-to-service and describe the time-to-service relationship with worker outcomes. To inform better healthcare funding practices, a comprehensive overview of the literature regarding the factors influencing time to service and its relationship with outcomes among workers with compensated musculoskeletal conditions is needed.

Research questions

-

i.

What factors are associated with time to service in studies of individuals with musculoskeletal conditions and accepted workers’ compensation claims?

-

ii.

What is the association between time to service and work and health outcomes in those individuals?

Methods

This scoping review study followed the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) framework [37] and was reported using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Supplementary file 1) [38]. The review protocol was pre-registered with the Open Science Foundation (link: https://osf.io/xjyd8).

Eligibility Criteria

Participants

Workers aged 15 years and above with an accepted workers’ compensation claim for a musculoskeletal condition affecting any body region were included [39]. Work-related musculoskeletal conditions at any stage of progression (i.e. acute, subacute, or chronic) were examined for inclusion.

Concept

We included studies that reported the time between an initial event, such as the initial report of musculoskeletal complaints, the date of claim acceptance, or primary index date and the services provided (time to service). We reviewed studies involving any treatment service (e.g. pharmacological and nonpharmacological) and diagnostic service (e.g. magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), X-ray, and ultrasound) funded by workers’ compensation. Evidence where the duration/average duration between the onset of injury and the first episode of care was not specified, and contact with healthcare providers for purposes other than treatment/diagnostic services (e.g. injury report writing and independent medical evaluations) were excluded.

Context

Personal injury reports involving transportation accidents (motor vehicle), the military, sports, and daily/home activities were excluded because injury cases in these settings are typically handled through alternative compensation schemes.

Type of Evidence Sources

Peer-reviewed studies published in English, including randomized and non-randomized controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohorts, case-control, analytical cross-sectional, and qualitative studies, were considered. Expert comments, perspective papers, conference abstracts, editorials, supplements, and magazine reports were excluded. Grey literature, such as dissertations and national survey data, was also excluded. Citation chaining was used to identify missing pertinent articles [40, 41].

Changes from the Original Protocol

Minor changes were made to the inclusion criteria indicated in the registered protocol. First, our preliminary search indicated that the working age group in certain important industries was older than 65, which was our original maximum cut-off age limit. As a result, we did not limit the maximum age in the review to 65 years. Second, grey literature, such as dissertations and national survey reports, expert opinions, viewpoint papers, and conference abstracts, was excluded from this review as we identified sufficient peer-reviewed literature to address our research questions. Third, the most recent search date for all databases included in this review (November 1, 2022) occurred after the date specified in the protocol (September 1, 2022). Finally, we added certain items to the protocol’s data charting table as new findings became available.

Search Strategy

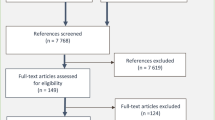

A preliminary search was conducted in the Medline (Ovid) database to identify text words and index keywords using the participant, concept, and context (PCC) approach [42]. Synonyms of musculoskeletal injury, time-to-treatment, work-related injury, and workers’ compensation were used. Terms of related concepts were combined using the Boolean OR operator, whereas the Boolean AND operator was used to combine different concepts. The search strategy was developed by two authors (THM and MDD) and was reviewed by a third author (GR) in consultation with a professional librarian. The final search was conducted on November 1, 2022, in six databases: MEDLINE (Ovid), EMBASE (Ovid), Psych Info (Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Scopus, and Web of Science. Peer-reviewed studies published in English until November 01, 2022, were included. The PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) displays the evidence screening steps, and Supplementary File 2 provides the Medline search strategy.

Study Selection

Citation management was conducted using Endnote software version 19.3 [43]. The citations were then exported to Covidence® for duplicate removal and evidence screening [44]. Two reviewers (THM and MDD) screened the titles and abstracts independently. The full-text studies that passed the initial screening step were obtained, and the same reviewers independently screened the full-text articles. Articles that did not fit the inclusion criteria were removed, and the reason was documented. Minimal disagreements were settled through discussion at all steps. Three authors (THM, MDD, and GR) were involved in the decision-making process regarding article exclusions.

Data Extraction/Charting

Data charting was conducted in Microsoft Excel using a standard data extraction template (Supplementary file 3). After checking for the comprehensiveness of the pilot findings conducted by one reviewer (MDD), another reviewer (THM) completed the entire data extraction. One reviewer (MDD) double-checked the extraction of seven articles at random, and the result was consistent between the authors. The characteristics of the study, including first author, year, title, journal, country, study design, data source, inclusion and exclusion criteria, study sample and sample size, and participant characteristics such as sex, age (mean with standard deviation, median with interquartile range), type of musculoskeletal conditions, type of services, main findings, and author conclusions were extracted. We charted detailed data regarding the use of time-to-service in each study (i.e. as an outcome, predictor, or both), information on the type of timing measure (e.g. continuous, categorical relative to a goal or certain treatment guideline, such as ‘early’), timing measurement (e.g. hours, days, weeks, and months ), timing start point, time-to-service average duration, factors affecting time-to-service and findings, and time-to-service predicting outcomes.

Summarizing and Reporting the Results

We first described the characteristics of the included studies. We then developed a narrative summary of time to service, followed by a synthesis table with the average duration and timing definitions. Next, we conducted a narrative summary of factors affecting time-to-service. Factors affecting time-to-service were categorized into four themes: individual, injury-related, workplace, and health services-related factors. The selection of the variables is based on the Behavioural Model of Health Services utilization, with a slight modification made to accommodate variables available within the workers’ compensation system administrative data, including work-related factors [45]. A descriptive summary of study outcomes (e.g. disability duration) was also produced, and the relationship between time to service and outcomes was described. We grouped worker outcomes into four categories following a previous study approach [25]: work outcomes, claim costs, healthcare utilization, and patient-reported health outcomes. Additionally, a summary table that includes the relationship between the outcomes and time to service, definitions of outcomes, and some study features was developed. At each stage of the process, the results were reviewed, refined, and feedback was shared among the authors until a final agreement was reached.

Results

Studies Selection

Electronic database searches yielded 3500 references in total. Citation chaining returned two additional relevant articles. After removing duplicates, 2345 records progressed to the title and abstract screening. Following title and abstract screening, 58 reports were passed for full-text review. During the full-text screening, 27 citations were excluded, leaving 31 eligible articles for inclusion. The PRISMA flow diagram (Fig. 1) fully reports the search results [46].

Study Characteristics

Table 1 presents the key characteristics of the included studies. Studies originated from the United States (n = 22) [40, 41, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66] and Canada (n = 9) [67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75], with most published from 2000 onwards (n = 27) [40, 41, 47,48,49,50, 52, 54, 55, 57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67, 69, 71,72,73, 75,76,77]. In (n = 5) studies, the study inception period/year of injury occurred before 2000 [53, 56, 64, 68, 74], and no year of injury was specified in (n = 2) studies [65, 67]. A retrospective cohort was the most common study design reported (n = 22) [40, 41, 47, 48, 54, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65, 69,70,71,72,73,74,75]. Other included studies used a prospective cohort (n = 6) [50,51,52, 55, 66, 68], randomized controlled trial (RCT) (n = 2) [53, 67], and cross-sectional (n = 1) [49] methods. Most studies used administrative data directly from workers’ compensation schemes (n = 20) ) [40, 41, 47, 48, 51, 54, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65, 69, 71, 75, 76] or with other studies using data sources such as employee interviews, medical records, and surveys (n = 11) [49, 50, 53, 55, 66,67,68, 72,73,74, 78]. The sample size ranged from 63 [67] to 137,175 participants [75].

Characteristics of Musculoskeletal Condition

A large number of studies included workers with low back pain in (n = 23) studies [40, 47, 49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60, 63,64,65, 67, 70,71,72,73,74]. More than one condition (multiple body parts) was reported in (n = 6) studies [48, 61, 62, 66, 68, 75], and (n = 1) study each for shoulder pain [69] and neck pain [41](Fig. 2).

Description of Time to Service

Time to service was most commonly used as a predictor in (n = 23) studies [41, 47, 48, 50, 52,53,54, 56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65, 67,68,69, 71, 73, 74] in reporting rather than as an outcome in (n = 3) studies [49, 55, 72]. Time to service was used as both a predictor and an outcome in (n = 5) studies [40, 51, 66, 70, 75]. Duration of time to service was measured from the date of injury in (n = 25) studies [40, 41, 47,48,49, 51,52,53,54, 56, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65, 67,68,69,70, 72,73,74], claim acceptance date in (n = 2) studies [71, 75], and index visit (i.e. first service) was used in (n = 4) studies [50, 55, 57, 66].

Measures of time to services varied depending on the type of services and musculoskeletal conditions involved. Several studies reported service timing categorically (or in binary terms) by classifying a service as either early or not. This usually occurred in studies of opioid, MRI, and physical therapy services for low back pain, where the measure of whether a service was early was based on guideline recommendations or evidence. For example, five studies involving magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) defined early service as service received within six weeks (n = 3) [52, 64, 77] and within the first 30 days (n = 2) [58, 60] of back conditions.

Overall, there was no standard timing definition, even for a particular service and condition. In addition, the reason for choosing different timing classifications within cohorts has not been described in some studies (Table 2).

Description of the Included Services

Services included in the eligible studies were: opioids in (n = 8) studies [50, 55, 59, 61, 62, 72, 73, 75], magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in (n = 5) studies [51, 52, 58, 60, 64], multiple (combination of services) in (i = 5) studies [49, 56, 69,70,71], surgery in (n = 4) studies [40, 41, 63, 65], physical therapy care in (n = 3) studies [66, 68, 74], visits to any healthcare provider in (n = 3) studies [47, 48, 54], interdisciplinary biopsychosocial intervention in (n = 2) studies [53, 67], and chiropractic care in (n = 1) study [57]; Fig. 3 .

Factors Affecting Time to Service

Eight studies identified the factors associated with time to service [40, 49, 55, 69, 70, 72, 75, 77]. These included individual, workplace, injury, and health service-related factors and are described in the following section (Table 3).

Individual-Related Factors

Gender

Five studies found a significant relationship between gender and the time to service [40, 49, 70, 72, 77]. Of these, three studies indicated male workers were associated with shorter time to service. The studies involved multiple services (i.e. medical doctor, chiropractor, physiotherapist, and nurse practitioner) used within a month, MRI within six weeks, and early opioid use within eight weeks of low back pain onset. A single study involving multiple services for low back injuries showed that males were more likely to receive delayed services [49], while another single study indicated that female workers received delayed surgery for back pain [40].

Age

Four studies found a significant relationship between age and time to service [69, 70, 72, 79]. Three studies found that older age was associated with longer time to service [40, 69, 70]. These three studies involved multiple services (i.e. medical doctor, chiropractor, physiotherapist, and nurse practitioner) and, surgery for low back pain, and assessment and clinical investigations for a shoulder injury as the service types. The fourth study reported that older workers used opioids early (i.e. within eight weeks) of low back injury [72].

Personal Income

A single study found that the time to service (i.e. first-line service involving a medical doctor, chiropractor, nurse practitioner, and physical therapist) for low back pain was more likely longer in high-income workers than in low-income workers [70].

Remoteness

One study of low back pain in workers found an association between residence in rural or urban/rural mixed regions and a shorter time to opioid use (i.e. within eight weeks of injury) [72].

Comorbidity

A single study demonstrated that workers with comorbidities used opioids soon (i.e. within eight weeks of a back injury) [72].

Tobacco Use

A single study found that workers with low back pain who used tobacco daily received opioids earlier (i.e. within six weeks of their initial healthcare visit) than workers who never used tobacco [55].

Functional Limitation

A single study found that experiencing a higher functional limitation was associated with a shorter time to service for low back pain (i.e. within the first four to sixteen weeks of injury) [49].

Work-Related Factors

Return to Work Programme

A single study found that the availability of a return-to-work programme in the workplaces was associated with a shorter time to services (first-line service) than workplaces with no return-to-work programme available [70].

Occupation

A single study reported that patients with low back pain whose occupation was clerical/sales experience a longer time to service (any visit to a provider) [49].

Employers' Doubt About Work-Relatedness of Injury

In one study, it has been observed that time to service was longer among workers with low back pain whose employers had doubts about occupational relatedness of injury [70].

The Number of Employees

One study showed that workers with low back pain in workplaces with a high number of employees experience a longer time to provider visits [70].

Injury-Related Factors

Injury Severity

Five studies demonstrated that injury severity was significantly associated with time to service [49, 55, 70, 72, 75, 77]. Three of the five studies indicated that time-to-service was shorter among the workers with greater injury severity. Of these studies, two studies involved early opioid use for low back pain [55] and for fractures, dislocations, and amputations [75], and another study involved early MRI for radiculopathy [77]. In contrast, two studies found that greater severe injuries were related to delayed services for low back conditions (visit to provider in both studies) [49, 70].

Previous Compensation History

A single study found that workers with a prior claim history had a shorter time to service for low back pain [70].

Pain

In one study, workers with greater pain severity were associated with early opioid use (i.e. within six weeks of healthcare visit) for low back conditions [55].

Year of Injury

A single included study involving early opioid prescription found that a more recent year of injury was associated with a longer time to service [72]. Two other included studies also reported decreasing trends in early opioid use with an increasing year of injury, but only descriptive results were documented [73, 75].

Health Service-Related Factors

The Type of Provider

One study showed that having a physiotherapist as the initial provider was associated with a longer time to service [70]. In another study, first consulting a surgeon was associated with early MRI utilization for low back pain (i.e. within six weeks of injury) [77].

Prescriber Demographics

Time to opioid use was shorter (i.e. within eight weeks of a low back injury) for workers who had their first visit with female and younger prescribers in a single study [72].

Overall, most studies examining the factors influencing the timing of services used quantitative administrative datasets and primarily focused on the characteristics of the injured workers. There was no qualitative study reported, and the factors related to health systems (e.g. the availability of providers), compensation schemes, insurance policies, and employers were insufficiently addressed.

Time to Service as a Predictor of Worker Outcomes

Table 4 provides a summary of outcome measures and definitions. There was a significant association between time to service and worker outcomes in (n = 25) studies [40, 41, 47, 48, 50, 52,53,54, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64, 66,67,68,69,70,71, 73,74,75, 77]. The majority of eligible studies that assessed the association between time to service and worker outcomes were retrospective designs, that involved low back conditions, and most studies were limited to North America. Studies on the relationship between time to service and patient-reported health outcomes, including mental health (e.g. depression and anxiety) were limited [65], and no studies were identified regarding addiction as an outcome among early opioid users. The timing definitions and outcome measures were also used inconsistently across studies.

In a study involving early physical therapy (i.e. service initiated at the initial point of healthcare contact) for upper and lower extremities, neck, back, and other body parts, time to service was associated with reduced costs and a shorter duration of care [66]. Another study involving early physical therapy received within 30 days [74] and one further study involving early evidence-based case-managed interdisciplinary (biopsychosocial approach) received within four to ten weeks of low back pain injury was associated with a greater rate of return to work [67]. Moreover, early physician assessment within four to sixteen weeks for shoulder injury was associated with improved patient-reported health outcomes, such as reduced pain exacerbation) [69].

Studies involving early opioid use (seven studies with various conditions) [50, 59, 61, 62, 71, 73, 75] and MRI (five studies with low back conditions) [52, 58, 60, 64, 77] demonstrated associations with longer duration of disability, increased costs, higher healthcare utilization, and poor patient-reported health outcomes. Moreover, a delayed visit to any provider for low back condition [54, 70] and surgery for neck injury (i.e. injury-to-surgery > 2 years) [41] was associated with negative outcomes (i.e. increased disability duration for a back condition and a decreased rate of return to work for neck injury).

Most studies reported more than one outcome. Therefore, we grouped the outcomes into related themes: work, cost, healthcare utilization, and patient-reported health outcomes. Each theme is discussed below.

Work Outcomes

The work outcome measures include work disability duration and return to work.

Work Disability Duration

The relationship between time to service and work disability duration was reported in sixteen studies [40, 47, 48, 50, 54, 57,58,59, 62,63,64, 68, 71, 73, 75, 76]. Studies described work disability duration using time to claim closure, length of disability, compensation duration, claim duration, duration of benefits, days absent from work, days lost work, and lost time work. Some studies used the concept of indemnity/wage replacement benefits to measure work disability duration [57, 59, 63, 64, 68, 71, 73, 70].

Studies involving early opioid use for low back conditions [50, 59, 71, 73] and for the lower extremity, upper extremity, back/neck, or multiple body parts [62], and early MRI for low back pain [58, 64] indicated a prolonged disability duration.

Five included studies found that early timing of health services is associated with reduced disability duration [40, 47, 48, 63, 67]. One study found that early interdisciplinary intervention (i.e. 4–10 weeks of low back pain onset) was associated with a decreased average number of days lost from work [67]. A detailed report is presented in Table 4.

Return to Work

The relationship between time to service and a return to work (RTW) outcome was reported in four studies [40, 41, 67, 74]. Two studies of participants with low back pain found a faster RTW outcome for time to surgery within two years of injury, compared to surgery performed two years after the injury [40, 41]. A cohort study of physical therapy in Canada (Quebec) revealed that physical therapy received early (i.e. within 30 days of low back pain) resulted in shorter time to RTW than those who did not receive physical therapy early [74]. Another randomized controlled trial report in Canada [67] also found that workers who received early (i.e. 4–10 weeks of a back injury) a biopsychosocial model-based interdisciplinary intervention exhibited significantly better RTW outcomes.

Claim Costs Outcomes

Nine studies reported the association between time to service and claim costs. The studies involving early opioids (i.e. 15 days within injury date) [59] and MRI (i.e. 6 weeks within injury report ) [52, 58, 60] for low back pain, and early physical therapy (i.e. within two days as soon as possible or as late as 70 days of injury ) for soft tissue acute musculoskeletal conditions in the back, upper, or lower limbs [68], and early multidisciplinary services for low back pain [53] were associated with increased medical and nonmedical costs.

Two studies indicated that surgery for low back pain within the first two years compared to surgery after two years [40, 63], and early physical therapy (i.e. physical therapy received at the initial point of care after injury report) for multiple body regions, was associated with decreased costs [66].

The effect of timing on cost outcomes was reported inconsistently. The majority of the studies reviewed addressed the relationship between early services and low back pain.

Healthcare Utilization Outcomes

Eight eligible studies assessed the relationship between time to service and overall healthcare utilization outcomes. Healthcare utilization outcomes reported in eligible studies include the duration of care, late opioid use (five and above opioids prescriptions between 30- and 730-day post-onset, subsequent surgery, spinal injection (i.e. caudal, facet lumbar/sacral, transforaminal lumbar/sacral, or sacroiliac joint injections), and overall healthcare utilization (e.g. frequency of visit, and intensity).

In one study, a decreased risk of long-term opioid use (i.e. an average of at least one prescription per month for three months or at least three consecutive prescription refills with less than one month between refills) has been shown among workers with low back pain using opioids early (i.e. within one month of injury date) and an increased risk among workers with shoulder injuries [61]. In another report, early opioid use (i.e. within 15 days of injury) for low back pain was associated with increased rates of subsequent opioid use and surgery services [59]. Four included studies indicated that early MRI (i.e. within 30–42 days of injury) for acute low back pain resulted in increased likelihood of spinal/ Lumbosacral injection and overall health care utilization [52, 58, 60, 77].

Generally, the studies indicated that early utilization of opioids and MRI were associated with the increased likelihood of greater healthcare utilization.

Patient-Reported Health Outcomes

Four included studies reported the association between time to service and patient-reported health outcomes [65, 68, 69, 75]. Patient-reported health outcomes included recovery, pain, health-related quality of life, mental health, and functional status. One eligible study involving surgery for low back pain (degenerative spinal disease) reported no significant relationship between time to service and pain, disability, mental health, and physical function [65]. Another single report found that early physical therapy (i.e. within as soon as two days or as late as seventy days of injury) for soft tissue musculoskeletal conditions, including the back, upper and lower limbs, was associated with improved pain, quality of life, and functional status [68]. Further, one included study showed that early opioids (i.e. within two weeks of claim acceptance) for back and related conditions were associated with delayed recovery [75]. Another study reported that time to early physician assessment (i.e. within 16 weeks of injury) for shoulder injury was associated with reduced pain symptoms [69].

Discussion

This scoping review identified a wide range of individual, injury, workplace, and health service-related factors associated with time to service in eight included studies. The relationship between time to service and worker outcomes was observed in twenty-five studies, and four categories of outcomes were identified across the studies: work outcomes (i.e. disability duration and return to work), healthcare utilization, claim costs, and patient-reported health outcomes. A shorter time to physical therapy care and interdisciplinary biopsychosocial interventions after injury report were associated with positive worker outcomes such as reduced pain, shorter time to return to work, lower likelihood of subsequent healthcare use, improved functional capacity, and decreased healthcare and indemnity cost. Conversely, early opioids use and MRI after injury reporting, against guideline recommendations, resulted in a longer duration of disability, increased costs, and healthcare utilization, and poorer patient-reported health outcomes in workers’ compensation accepted claims for musculoskeletal conditions.

Description of Time to Services

We noted variability in measuring and defining time to services. This variation may be because our review included any study that examined the timing of services. Moreover, the differences could be because the included studies used different milestones as starting points for the services, such as injury date, claim acceptance date, or initial point of care. Further, the included studies also employed different units of measurement for time to services, such as days, weeks, or months. A previous systematic review study by Arnold et al. supports the heterogeneity observed in our findings [34]. Arnold et al. measured the timing of physical therapy for acute low back pain and found varying definitions of early and delayed timing in the documented evidence. Authors of the study defined early as within 30 days of index date compared to delayed or usual care. Another prior systematic review study by Ojha et al. [25] found that most studies they examined defined early physical therapy as a service initiated within 14 days of the injury or index visit for musculoskeletal conditions.

We also found numerous studies that reported services as being accessed ‘early’ compared to not early. A possible explanation may be that studies that included services such as MRI and opioids typically involved early as defined by certain clinical practice guidelines. In our scoping review, 74% of the included studies examined low back pain conditions- a common musculoskeletal condition [80], most of which measured the prevalence and impact of the non-guideline adherent timing of certain services, including MRI and Opioids. Low back pain represents a substantial portion of workers’ compensation claims, so studies testing whether healthcare is guideline adherent are not necessarily surprising. These studies identified that services were frequently offered during the acute phase of low back conditions, even when such services were not in line with practice guideline recommendations. Furthermore, many studies reporting the timing of services relative to best practice care/ guidelines involved workers with low back pain [53, 67, 74].

Factors Influencing Time to Services

Addressing the factors associated with health service timing could help identify the barriers to timely access to appropriate services. In our review, time to service was shorter for male workers experiencing low back pain in studies involving services with visits to any provider, early MRI, and opioids [70, 72, 77]. This report was in line with the findings of prior research [81, 82]. It has been shown that male workers are more likely to experience injuries and fatalities than females [83], which may be a possible reason for male workers to seek healthcare services earlier than females. Our study also found that the time to service was longer for female workers in a study involving surgery for low back conditions [40]. It has previously been reported that females experience a longer time to health services due to facing more barriers, such as family responsibility [84]. Another study also supports the finding of our review in that women workers experienced a longer waiting time for consultation and surgical treatment for a compensable shoulder injury, suggesting that the difference may be due to the combination of biological and social differences [85]. The current scoping review also demonstrated that other non-modifiable factors including older age were associated with time to service [40, 69, 70, 72]. Moreover, the time to opioid use was shorter for low back pain patients with comorbidities and those in rural and remote areas [72]. People with comorbidities may experience greater pain symptoms, leading to prompt healthcare-seeking practice.

Workplace factors, such as the availability of early return to work programmes within organizations, were associated with a shorter time to service for low back pain [70]. This may be due to the fact that workers in workplaces with return to work programmes available may have better information and awareness on early injury reporting and health-seeking practices.

Included studies also indicated that the severity of injury significantly influences time to service [49, 51, 55, 70, 72, 75]. Earlier study shows that a greater injury severity is associated with a shorter delay in healthcare consultation [86]. In the current review, a more recent year of injury was significantly associated with a longer time to service in a study involving early opioid prescriptions [72]. The decreasing pattern of receiving early opioids may be attributed to the increasing awareness of the potential adverse effects of early opioids or temporal changes related to workers’ compensation policies regarding early opioid reimbursement. Of the studies screened, Gross et al. reported a decreasing trend of early opioid prescriptions, with rates declining from 6.7% in 2000 to 4.8% in 2005 [75]. Moreover, a study by Carnide and colleagues demonstrated a reduction rate of early opioid prescriptions from 20.3% in 1998/1999 to 13.2% in 2000/2009 [73]. However, the authors did not report the significance of the association with time to service. Of the health service-related factors, one study demonstrated that the time to service for low back pain was longer when the type of first provider is a physiotherapist [70]. There is a lack of studies to compare these findings.

The included studies rarely reported on factors associated with health systems (e.g. referral process, availability of services), and compensation policies (e.g. insurance coverage). It is unclear why these were not studied. It may be that most studies used administrative claims data or that data was taken from a single jurisdiction, meaning comparisons of health systems or insurance policies were not possible.

Association Between Time to Service and Worker Outcomes

Early access to evidence-based services, such as physical therapy and case-managed interdisciplinary biopsychosocial interventions, was associated with improved outcomes (i.e. a shorter duration of disability/a higher rate of return to work, lower claim costs, decreased healthcare duration, and improved patient-reported health outcomes (e.g. improved functional status, quality of life, and less pain symptoms)). For example, a study by Ehrmann-Feldman et al. shows that physical therapy within a month (early) of a back injury that involves various treatments (i.e. exercise, heat, ultrasound, back education, manipulation, and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation) is associated with a higher rate of return to work within 60 days than physical therapy utilized later [74]. This positive association was consistent across conditions affecting various body parts, including the upper and lower extremities, neck, back, shoulder, and other parts. Consistent with the present study, previous studies demonstrated that early treatment with best practice services was associated with desired outcomes [25, 87,88,89].

In the present review, a prospective study by Sinclair et al. indicated that early physical therapy utilization was associated with increased claim costs [20]. This report contradicts with a study by Young et al. [90]. The differences could be related to differences in the definition of timing and study population. While timely, appropriate care has been promoted as a good thing for recovery in people with various musculoskeletal conditions, our review has highlighted the challenges with testing that theory. For example, the study by Sinclair et al. defined early physical therapy as active, exercise, and education programme based-intervention initiated within two days or as delayed as 70 days of soft tissue musculoskeletal injury onset compared to usual care [68], whereas the study by Young et al. defined early physical therapy as treatment started on the same day of provider contact or within 30 days of pain diagnosis [90]. Understanding the context and characteristics of patients who benefit the most from early physical therapy assists in clarifying these disparities and guides informed decisions.

The association between early services and outcomes varied depending on the type of services provided. For example, surgery within one year compared to surgery after one year [63] and surgery within two years compared to surgery after two years of low back injury [40] resulted in a faster return to work rate, shorter disability duration, lower claim costs, and reduced healthcare utilization. For a neck injury, a lower rate of return to work was observed for surgery two years after the injury than surgery within two years [41].

Studies involving early MRI and opioid prescription demonstrated negative worker outcomes. Prior research suggests that early MRI has been associated with unfavourable outcome [51, 91]. Guidelines discourage early timing of diagnostic imaging (e.g. MRI) for conditions such as low back pain in the absence of severe underlying conditions [92, 93]. Consistent with literature findings [27, 94], early opioid use was associated with worse outcomes, with consistent results across the studies. Early opioids may lead to opioid addiction and prolonged use [95]. We found no studies that reported the effects of early opioid use on addiction in workers with low back conditions. Future research may use a prospective study to investigate the relationship between early opioids and subsequent addiction in patients managed under workers’ compensation systems.

Limitations of the Current Scoping Review

This scoping review included studies with an array of data sources. Administrative datasets were most common, likely due to our defined population. Some studies used a combination of datasets, including administrative data sets linked to medical records and population data, surveys, and patient interviews. Included studies also used different study designs, such as randomized controlled studies, prospective and retrospective designs with statistical adjustments that were used to control potential confounders and manage missing data. Moreover, the current scoping review covered a broad range of conditions and services, with a robust report on how the timing of healthcare services funded through the workers’ compensation system affects the outcomes of individuals suffering from musculoskeletal conditions.

Some limitations mentioned by the studies examined include limited reliability of administrative data and a lack of a direct measure of injury severity (e.g. pain, intensity, and functional limitations), or missed potential variables within workers’ compensation administrative data for controlling confounders [57, 70, 72, 75]. Besides, some studies were descriptive [56, 69], included small sample sizes [53, 56, 65, 67, 96], or were cross-sectional [49]. There were also inconsistent timing definitions and outcome measurements across the studies and services, which make it challenging to compare study reports. Consistent outcome measurements may enable cross-study comparison and findings synthesis. Furthermore, the relatively wide range of concepts covered in the current scoping review limits our ability to deeply explore each construct. Despite these limitations, the findings of the included studies demonstrated a significant relationship between various characteristics and time to services, and its effect on outcomes.

Implications

Variability in outcome measures used by included studies highlights the need for standardization of measures of healthcare service timing. A consistent outcome measure could assist in comparing the timing of various services between healthcare systems and insurance systems for the management of musculoskeletal conditions, such as low back pain within the workers’ compensation system [97]. Moreover, several factors associated with the timing of health services for workers’ compensation system accepted claims of musculoskeletal conditions highlight the need to consider barriers to timely access to appropriate services, as well as characteristics that drive early services with little evidence support. The provision of interventions that consider the need for individual patient characteristics, such as age, gender, injury severity, occupation, and medical history (e.g. comorbidities), may enable to achieve favourable worker outcomes and reduce potential costs associated with workers compensation claims. Moreover, workers’ compensation policies need to ensure that strategies to reduce the practice of early services with negative effects are in place. This could be accomplished through awareness raising and educating providers and patients about the risks and benefits of early services that lack evidence of effectiveness, such as opioids and MRI, and providing adequate access to early services with superior outcomes, such as physical therapy. Graves et al. for example, found that implementing a utilization review programme for advanced imaging reduced the trends of services with minimal benefits, including MRI and injection [98]. The study also showed that the utilization review strategy was associated with substantially lower claim costs, shorter average durations of disability, and a lower percentage of workers on disability payments.

Subject to the common drawback of a scoping review, we did not assess the methodological quality of the included studies. Acknowledging the breadth of a scoping review, the wider nature of services and conditions contained in the review may affect the representativeness of the study to a particular group or service. Moreover, the study included only peer-reviewed journals published in English, which may lead to the study selection bias. Finally, because our search was limited to the workers’ compensation context, findings may not be translated to the general and uncompensated populations.

Conclusion

This scoping review found that time to service for individuals with compensated musculoskeletal conditions was associated with several individual, injury, workplace, and health service-related factors. The majority of the studies indicated the relationship between time to service and worker outcomes, with early access to physical therapy and biopsychosocial interventions indicating an increased rate of return to work for low back conditions, reduced pain for shoulder injury, improved functional status, health-related quality of life, and pain symptoms for the back, upper or lower limb musculoskeletal conditions, decreased duration of care and claim costs in patients with upper extremity, lower extremity, neck, and back conditions. Conversely, early opioids and MRI use were found to be associated with prolonged disability duration, increased claim costs, poorer patient-reported outcomes, and a greater likelihood of subsequent healthcare use, with consistent reports across studies. This review suggests that there is a need to consider various individual and contextual factors and develop strategies to minimize the early use of opioids and MRI and promote access to early services with better outcomes (e.g. physical therapy and interdisciplinary biopsychosocial intervention) for the management of compensable musculoskeletal conditions. Further study may be required to explore the various contextual factors affecting health service timing and its impacts on compensation outcomes.

Abbreviations

- CINAHL:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature ICD:International Classification of Diseases

- LBP:

-

Low back pain

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- NSAIDs:

-

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- PRISMA-ScR:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Reviews

- RCT:

-

Randomized controlled trial

- USA:

-

United States of America

- WRMSD:

-

Work-related musculoskeletal disorders

References

Loisel P, Anema JR. Handbook of Work Disability Prevention and Management. New York 2013.

Collie A, Lane T, Hatherell L, McLeod C. Compensation policy and return to work effectiveness (ComPARE) project: introductory report. In.: Research Report; 2015.

Lipscomb HJ, Schoenfisch AL, Cameron W, Kucera KL, Adams D, Silverstein BA. Contrasting patterns of care for musculoskeletal disorders and injuries of the upper extremity and knee through workers’ compensation and private health care insurance among union carpenters in Washington State, 1989 to 2008. Am J Ind Med. 2015;58(9):955–963.

Oakman J, Clune S, Stuckey R. Work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Australia. Safe Work Australia: Canberra, Australia 2019.

Macpherson RA, Lane TJ, Collie A, McLeod CB. Age, sex, and the changing disability burden of compensated work-related musculoskeletal disorders in Canada and Australia. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):1–11.

Safe Work Australia. : Australian Workers’ Compensation Statistics. Available at: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-12/australian_workers_compensation_statistics_2020-21.pdf. 2020–2021.

Safe Work Australia. : Comparative Performance Monitoring (CPM) 24th edition indicators. Workers’ compensation funding. Available at: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-12/cpm_24_-_workers_compensation_funding.

Health and Safety Executive. Health and safety at work. Key facts. Summary statistics for Great Britain 2022. https://www.hse.gov.uk/statistics/overall/hssh2122.pdf.

Kosny A, Lifshen M, Yanar B, Tonima S, MacEachen E, Furlan A, Koehoorn M, Beaton D, Cooper J, Neis B. The role of healthcare providers in return to work. Int J Disabil Manag. 2018;13:e3.

Xia T, Collie A, Newnam S, Lubman DI, Iles R. Timing of health service use among truck drivers after a work-related injury or Illness. J Occup Rehabil. 2021;31(4):744–753.

Safe Work Australia. Comparison of worker’ compensation arrangements in Australia and New Zealand: Australian Government-Safe Work Australia, 2012.

Wickizer TM, Franklin G, Plaeger-Brockway R, Mootz RD. Improving the quality of workers’ compensation health care delivery: the Washington State Occupational Health Services Project. Milbank Q. 2001;79(1):5–33.

van Duijn M, Eijkemans MJ, Koes BW, Koopmanschap MA, Burton KA, Burdorf A. The effects of timing on the cost-effectiveness of interventions for workers on sick leave due to low back pain. Occup Environ Med. 2010;67(11):744–50.

Stover B, Wickizer TM, Zimmerman F, Fulton-Kehoe D, Franklin G. Prognostic factors of long-term disability in a workers’ compensation system. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49:31–40.

Kominski GF, Pourat N, Roby DH, Cameron ME. Return to work and degree of recovery among injured workers in California’s Workers’ Compensation system. J Occup Environ Med. 2008;50:296–305.

Crook J, Moldofsky H. The probability of recovery and return to work from work disability as a function of time. Qual Life Res. 1994;3:97–S109.

Vora RN, Barron BA, Almudevar A, Utell MJ. Work-related chronic low back pain—return-to-work outcomes after referral to interventional pain and spine clinics. Spine. 2012;37(20):E1282–E1289.

McIntosh G, Frank J, Hogg-Johnson S, Bombardier C, Hall H. 1999 young investigator research award winner: prognostic factors for time receiving workers’ compensation benefits in a cohort of patients with low back pain. Spine. 2000;25(2):147.

Kucera KL, Lipscomb HJ, Silverstein B, Cameron W. Predictors of delayed return to work after back injury: a case–control analysis of union carpenters in Washington State. Am J Ind Med. 2009;52(11):821–830.

Kumar D, Neogi T, Peloquin C, Marinko L, Camarinos J, Aoyagi K, Felson DT, Dubreuil M. Delayed timing of physical therapy initiation increases the risk of future opioid use in individuals with knee osteoarthritis: a real-world cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2022-106044.

Voss MR, Homa JK, Singh M, Seidl JA, Griffitt WE. Outcomes of an interdisciplinary work rehabilitation program. Work. 2019;64(3):507–514.

Kosny A, MacEachen E, Ferrier S, Chambers L. The role of health care providers in long term and complicated workers’ compensation claims. J Occup Rehabil. 2011;21(4):582–90.

Elbers NA, Chase R, Craig A, Guy L, Harris IA, Middleton JW, Nicholas MK, Rebbeck T, Walsh J, Willcock S. Health care professionals’ attitudes towards evidence-based medicine in the workers’ compensation setting: a cohort study. BMC Med Inf Decis Mak. 2017;17:1–12.

Hagen EM, Eriksen HR, Ursin H. Does early intervention with a light mobilization program reduce long-term sick leave for low back pain? Spine. 2000;15:1973–6.

Ojha HA, Wyrsta NJ, Davenport TE, Egan WE, Gellhorn AC. Timing of physical therapy initiation for nonsurgical management of musculoskeletal disorders and effects on patient outcomes: a systematic review. J Orthop Sports Phys Therapy. 2016;46(2):56–70.

Gilbert F, Grant A, Gillan M, Vale L, Scott N, Campbell M, Wardlaw D, Knight D, McIntosh E, Porter R. Does early magnetic resonance imaging influence management or improve outcome in patients referred to secondary care with low back pain? A pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess. 2004;8:1.

Shraim BA, Shraim MA, Ibrahim AR, Elgamal ME, Al-Omari B, Shraim M. The association between early MRI and length of disability in acute lower back pain: a systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):1–12.

Carnide N, Hogg-Johnson S, Cote P, Irvin E, Van Eerd D, Koehoorn M, Furlan AD. Early prescription opioid use for musculoskeletal disorders and work outcomes. Clin J Pain. 2017;33(7):647–58.

Kucera KL, Lipscomb HJ, Silverstein B. Medical care surrounding work-related back injury claims among Washington State union carpenters, 1989–2003. Work. 2011;39(3):321–30.

Cancelliere C, Donovan J, Stochkendahl MJ, Biscardi M, Ammendolia C, Myburgh C, Cassidy JD. Factors affecting return to work after injury or Illness: best evidence synthesis of systematic reviews. Chiropr Man Ther. 2016;24:1–23.

Brijnath B, Mazza D, Kosny A, Bunzli S, Singh N, Ruseckaite R, Collie A. Is clinician refusal to treat an emerging problem in injury compensation systems? BMJ open. 2016;6(1):e009423.

Dembe AE. Access to medical care for occupational disorders: difficulties and disparities. J Health Social Policy. 2001;12(4):19–33.

Rudolph L, Dervin K, Cheadle A, Maizlish N, Wickizer T. What do injured workers think about their medical care and outcomes after work injury? J Occup Environ Med. 2002;44:425–34.

Arnold E, La Barrie J, DaSilva L, Patti M, Goode A, Clewley D. The effect of timing of physical therapy for acute low back pain on health services utilization: a systematic review. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2019;100(7):1324–38.

McDevitt AW, Cooper CG, Friedrich JM, Anderson DJ, Arnold EA, Clewley DJ. Effect of physical therapy timing on patient reported outcomes for individuals with acute low back pain: a systematic review with meta analysis of randomized controlled trials. PM&R. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1002/pmrj.12984.

Zigenfus GC, Yin J, Giang GM, Fogarty WT. Effectiveness of early physical therapy in the treatment of acute low back musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42:35–9.

Peters MDJ, Marnie C, Tricco AC, Pollock D, Munn Z, Alexander L, McInerney P, Godfrey CM, Khalil H. Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evid Implement. 2021;19(1):3–10.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group* P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(4):264–9.

Australian Safety and Compensation Council Type of Occurrence Classification System. Third edition (revision one) May 2008. Available at: https://www.safeworkaustralia.gov.au/system/files/documents/1702/typeofoccurrenceclassificationsystemtoocs3rdeditionrevision1.pdf.

Ren BO, Rothfusz CA, Faour M, Anderson JT, O’Donnell JA, Haas AR, Percy R, Woods ST, Ahn UM, Ahn NU. Shorter time to surgery is associated with better outcomes for spondylolisthesis in the workers’ compensation population. Orthopedics. 2020;43(3):154–60.

Faour M, Anderson JT, Haas AR, Percy R, Woods ST, Ahn UM, Ahn NU. Surgical and functional outcomes after multilevel cervical fusion for degenerative disc disease compared with fusion for radiculopathy: a study of workers’ compensation population. Spine. 2017;42(9):700–6.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32.

The EndNote Team. Endnote. In., EndNote X9 Edn. Philadelphia, PA: Clarivate; 2013.

Covidence systematic review software., Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, Australia. Available at www.covidence.org.

Andersen RM. National health surveys and the behavioral model of health services use. Med Care. 2008;46:647–53.

Transparent Reporting of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses. PRISMA for Scoping Reviews. Available at:http://www.prisma-statement.org/Extensions/ScopingReviews.

Besen E, Harrell IIIM, Pransky G. Lag times in reporting injuries, receiving medical care, and missing work: associations with the length of work disability in occupational back injuries. J Occup Environ Med. 2016;58(1):53.

Besen E, Young A, Gaines B, Pransky G. Lag times in the work disability process: differences across diagnoses in the length of disability following work-related injury. Work. 2018;60(4):635–48.

Côté P, Baldwin ML, Johnson WG. Early patterns of care for occupational back pain. Spine. 2005;30(5):581–7.

Franklin GM, Stover BD, Turner JA, Fulton-Kehoe D, Wickizer TM. Early opioid prescription and subsequent disability among workers with back injuries: the disability risk identification study cohort. Spine. 2008;33(2):199–204.

Graves JM, Fulton-Kehoe D, Jarvik JG, Franklin GM. Early imaging for acute low back pain: one-year health and disability outcomes among Washington State workers. Spine. 2012;37(18):1617–27.

Graves JM, Fulton-Kehoe D, Jarvik JG, Franklin GM. Health care utilization and costs associated with adherence to clinical practice guidelines for early magnetic resonance imaging among workers with acute occupational low back pain. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(2):645–65.

Greenwood JG, Wolf HJ, Pearson RJC, Woon CL, Posey P, Main CF. Early intervention in low back disability among coal miners in West Virginia: negative findings. J Occup Med. 1990;32:1047–52.

Sinnott P. Administrative delays and chronic disability in patients with acute occupational low back injury. J Occup Environ Med. 2009;51:690–9.

Stover BD, Turner JA, Franklin G, Gluck JV, Fulton-Kehoe D, Sheppard L, Wickizer TM, Kaufman J, Egan K. Factors associated with early opioid prescription among workers with low back injuries. J Pain. 2006;7(10):718–25.

Tacci JA, Webster BS, Hashemi L, Christiani DC. Healthcare utilization and referral patterns in the initial management of new-onset, uncomplicated, low back workers’ compensation disability claims. J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40:958–63.

Wasiak R, Kim J, Pransky GS. The association between timing and duration of chiropractic care in work-related low back pain and work-disability outcomes. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49:1124–34.

Webster BS, Cifuentes M. Relationship of early magnetic resonance imaging for work-related acute low back pain with disability and medical utilization outcomes. J Occup Environ Med. 2010;52:900–7.

Webster BS, Verma SK, Gatchel RJ. Relationship between early opioid prescribing for acute occupational low back pain and disability duration, medical costs, subsequent Surgery and late opioid use. Spine. 2007;32(19):2127–32.

Webster BS, Choi Y, Bauer AZ, Cifuentes M, Pransky G. The cascade of medical services and associated longitudinal costs due to nonadherent magnetic resonance imaging for low back pain. Spine. 2014;39(17):1433.

Heins SE, Feldman DR, Bodycombe D, Wegener ST, Castillo RC. Early opioid prescription and risk of long-term opioid use among US workers with back and shoulder injuries: a retrospective cohort study. Inj Prev. 2016;22(3):211–5.

Haight JR, Sears JM, Fulton-Kehoe D, Wickizer TM, Franklin GM. Early high-risk opioid prescribing practices and long-term disability among injured workers in Washington State, 2002 to 2013. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62(7):538.

Lavin RA, Tao X, Yuspeh L, Bernacki EJ. Temporal relationship between lumbar spine surgeries, return to work, and workers’ compensation costs in a cohort of injured workers. J Occup Environ Med. 2013;55(5):539–43.

Mahmud MA, Webster BS, Courtney TK, Matz S, Tacci JA, Christiani DC. Clinical management and the duration of disability for work-related low back pain. J Occup Environ Med. 2000;42:1178–87.

Patel MR, Jacob KC, Lynch CP, Cha ED, Patel SD, Prabhu MC, Vanjani NN, Pawlowski H, Singh K. Impact of time to surgery for patients using workers’ compensation insurance undergoing minimally invasive transforaminal lumbar Interbody Fusion: a preliminary analysis of clinical outcomes. World Neurosurg. 2022;160:e421–9.

Phillips TD, Shoemaker MJ. Early access to physical therapy and specialty care management for American workers with musculoskeletal injuries. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(4):402–11.

Schultz IZ, Crook JM, Berkowitz J, Meloche GR, Prkachin KM, Chlebak CM. Early intervention with compensated lower back-injured workers at risk for work disability: fixed versus flexible approach. Psychol Injury Law. 2013;6(3):258–76.

Sinclair SJ, Hogg-Johnson S, Mondloch MV, Shields SA. The effectiveness of an early active intervention program for workers with soft-tissue injuries: the early claimant cohort study. Spine. 1997;22(24):2919–31.

Razmjou H, Boljanovic D, Lincoln S, Geddes C, Macritchie I, Virdo-Cristello C, Richards RR. Examining outcome of early physician specialist assessment in injured workers with shoulder complaints. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2015;16(1):1–8.

Blanchette M-A, Rivard M, Dionne CE, Steenstra I, Hogg-Johnson S. Which characteristics are associated with the timing of the first healthcare consultation, and does the time to care influence the duration of compensation for occupational back pain? J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(3):359–68.

Busse JW, Ebrahim S, Heels-Ansdell D, Wang L, Couban R, Walter SD. Association of worker characteristics and early reimbursement for physical therapy, chiropractic and opioid prescriptions with workers’ compensation claim duration, for cases of acute low back pain: an observational cohort study. BMJ open. 2015;5(8):e007836.

Carnide N, Hogg-Johnson S, Côté P, Koehoorn M, Furlan AD. Factors associated with early opioid dispensing compared with NSAID and muscle relaxant dispensing after a work-related low back injury. Occup Environ Med. 2020;77(9):637–47.

Carnide N, Hogg-Johnson S, Koehoorn M, Furlan AD, Côté P. Relationship between early prescription dispensing patterns and work disability in a cohort of low back pain workers’ compensation claimants: a historical cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(8):573–81.

Ehrmann-Feldman D, Rossignol M, Abenhaim L, Gobeille D. Physician referral to physical therapy in a cohort of workers compensated for low back pain. Phys Ther. 1996;76(2):150–6.

Gross DP, Stephens B, Bhambhani Y, Haykowsky M, Bostick GP, Rashiq S. Opioid prescriptions in Canadian workers’ compensation claimants: prescription trends and associations between early prescription and future recovery. Spine. 2009;34(5):525–31.

Blanchette M-A, Rivard M, Dionne CE, Hogg-Johnson S, Steenstra I. Association between the type of first healthcare provider and the duration of financial compensation for occupational back pain. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27:382–92.

Graves JM, Fulton-Kehoe D, Martin DP, Jarvik JG, Franklin GM. Factors associated with early magnetic resonance imaging utilization for acute occupational low back pain: a population-based study from Washington State workers’ compensation. Spine. 2012;37(19):1708–18.

Grant GM, O’Donnell ML, Spittal MJ, Creamer M, Studdert DM. Relationship between stressfulness of claiming for injury compensation and long-term recovery: a prospective cohort study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(4):446–53.

Ren BO, O’Donnell JA, Anderson JT, Haas AR, Percy R, Woods ST, Ahn UM, Ahn NU. Time to Surgery affects Return to work Rates for workers’ compensation patients with single-level lumbar disk herniation. Orthopedics. 2021;44(1):e43–9.

World Health Organization. : Musculoskeletal health 2022. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/musculoskeletal-conditions.

Carrière G, Sanmartin C. Waiting time for medical specialist consultations in Canada, 2007. Health Rep. 2010;21(2):7.

Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, Williams JI, Harvey B, Glazier R, Badley EM. Differences between men and women in the rate of use of hip and knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(14):1016–22.

Nonfatal Occupational Injuries and Illnesses Requiring Days Away From Work, 2015: News Release. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), U.S. Department of Labor, November 10, 2016.

Wellstood K, Wilson K, Eyles J. Reasonable access’ to primary care: assessing the role of individual and system characteristics. Health Place. 2006;12(2):121–30.

Razmjou H, Lincoln S, Macritchie I, Richards RR, Medeiros D, Elmaraghy A. Sex and gender disparity in pathology, disability, referral pattern, and wait time for Surgery in workers with shoulder injury. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2016;17(1):1–9.

Feldman DE, Bernatsky S, Haggerty J, Leffondré K, Tousignant P, Roy Y, Xiao Y, Zummer M, Abrahamowicz M. Delay in consultation with specialists for persons with suspected new-onset rheumatoid arthritis: a population‐based study. Arthritis Care Res. 2007;57(8):1419–25.

Hon S, Ritter R, Allen DD. Cost-effectiveness and outcomes of direct access to physical therapy for musculoskeletal disorders compared to physician-first access in the United States: systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys TherDoi. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/pzaa201.

Fritz JM, King JB, McAdams-Marx C. Associations between early care decisions and the risk for long-term opioid use for patients with low back pain with a new physician consultation and initiation of opioid therapy. Clin J Pain. 2018;34(6):552–8.

Oral A. Is multidisciplinary biopsychosocial rehabilitation effective on pain, disability, and work outcomes in adults with subacute low back pain? A Cochrane Review summary with commentary. Musculoskelet Sci Pract. 2019;44:102065.

Young JL, Snodgrass SJ, Cleland JA, Rhon DI. Timing of physical therapy for individuals with patellofemoral pain and the influence on healthcare use, costs and recurrence rates: an observational study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):1–9.

Shraim M, Cifuentes M, Willetts JL, Marucci-Wellman HR, Pransky G. Why does the adverse effect of inappropriate MRI for LBP vary by geographic location? An exploratory analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2019;20:1–11.

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. : Low back pain and sciatica in over 16s: assessment and management. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng59/resources/low-back-pain-and-sciatica-in-over-16s-assessment-and-management-pdf-183752169363.

Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT Jr, Shekelle P, Owens DK. Physicians CEASotACo, Panel* tACoPAPSLBPG: diagnosis and treatment of low back pain: a joint clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians and the American Pain Society. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):478–91.

Szucs K, Gray SE. Impact of opioid use on duration of time loss after work-related lower limb injury. J Occup Rehabil. 2022;33(1):71–82.

Chou R, Turner JA, Devine EB, Hansen RN, Sullivan SD, Blazina I, Dana T, Bougatsos C, Deyo RA. The effectiveness and risks of long-term opioid therapy for chronic pain: a systematic review for a National Institutes of Health Pathways to Prevention Workshop. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162(4):276–86.

Schultz I, Crook J, Berkowitz J, Milner R, Meloche G, Lewis M. A prospective study of the effectiveness of early intervention with high-risk back-injured workers—A pilot study. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18(2):140–51.

Chiarotto A, Terwee CB, Ostelo RW. Choosing the right outcome measurement instruments for patients with low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2016;30(6):1003–20.

Graves JM, Fulton-Kehoe D, Jarvik JG, Franklin GM. Impact of an advanced imaging utilization review program on downstream health care utilization and costs for low back pain. Med Care. 2018;56(6):520–8.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Waikit Lee for contributing to a study screening and Mario Sos, a liaison librarian at Monash University, for contributing to the literature search.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The author THM received the Monash Graduate Scholarship and Monash International Tuition Scholarship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

THM, AC, and GR designed the study; THM, MDD, and GR contributed to the literature search; THM and MDD screened the articles; THM and MDD extracted data; THM synthesized, interpreted evidence and wrote the manuscript draft; THM, MDD, AC, and GR reviewed and finalized the manuscript. All authors reviewed the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This study was a review of previous evidence. Therefore, ethics approval was not required.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Mekonnen, T.H., Di Donato, M., Collie, A. et al. Time to Service and Its Relationship with Outcomes in Workers with Compensated Musculoskeletal Conditions: A Scoping Review. J Occup Rehabil (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-023-10160-0

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-023-10160-0