Abstract

Purpose

As stigma is a barrier to work participation of unemployed people with mental health issues/mental illness (MHI), a stigma awareness intervention can be helpful to make informed decisions about disclosing MHI. The aim of this process evaluation was to investigate the feasibility of a stigma awareness intervention, to explore experiences of clients and their employment specialists; and to give recommendations for further implementation.

Methods

The intervention consisted of a stigma awareness training for employment specialists and a decision aid tool for their clients with (a history of) MHI. For the process evaluation, six process components of the Linnan & Stecklar framework were examined: recruitment, reach, dose delivered, dose received, fidelity and context. Using a mixed-methods design, quantitative and qualitative data were collected and analyzed.

Results

The six components showed the intervention was largely implemented as planned. Questionnaire data showed that 94% of the clients found the tool useful and 87% would recommend it to others. In addition, more than half (54%) indicated the tool had been helpful in their disclosure decision. Qualitative data showed that participants were mainly positive about the intervention. Nevertheless, only a minority of clients and employment specialists had actually discussed the tool together. According to both, the intervention had increased their awareness of workplace stigma and the disclosure dilemma.

Conclusion

The implementation of a stigma awareness intervention was feasible and did increase stigma awareness. Experiences with the intervention were mainly positive. When implementing the tool, it is recommended to embed it in the vocational rehabilitation system, so that discussing the disclosure dilemma becomes a routine.

Trail Register

The study was retrospectively registered at the Dutch Trial Register (TRN: NL7798, date: 04-06-2019).

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Background

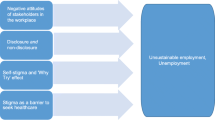

People with mental health issues/mental illness (MHI) are 3 to 7 times more often unemployed than people without MHI [1, 2]. This is problematic, because being unemployed is associated with personal, social and economic consequences such as poorer (mental) health and financial strains [3,4,5] and under favourable conditions, employment contributes to health, wellbeing and recovery [1, 6]. There is growing evidence showing that stigma and discrimination are important barriers for the employment opportunities of people with MHI [7,8,9,10]. Stigma is the process of (negatively) labelling and excluding groups of people from society, which subsequently could lead to discriminatory behavior [11]. Link and Phelan’s theory [11] conceptualize stigma in four different components, i.e. (1) distinguishing and labeling human differences, (2) Cultural beliefs link these labels to undesirable characteristics and negative stereotypes; (3) Labels are placed in distinct categories to accomplish separation of ‘us’ from ‘them’; and (4) Because of labels, status loss and discrimination is experienced. Negative stereotypes and discrimination on the part of employers, as well as internalized stigma, i.e. turning the stigmatizing stereotypes to themselves, among people with MHI, could hamper finding and retaining paid employment [7, 12,13,14,15,16]. Furthermore, a lack of work experience could result in less return to work self-efficacy [17] and subsequently in the ‘why try’-effect (i.e. no longer participating in activities because of fear of discrimination) [8, 18].

Decisions about disclosure of a MHI to employers are complex and several studies have suggest that deliberate decisions are of importance for the (re-)employment success of people with MHI [7, 19,20,21], but are also complicated and personal [22]. Disclosure of MHI can lead to positive outcomes such as support or adjustments in the work environment [19], but could also have negative consequences such as stigma and discrimination (e.g. not getting hired) [19, 20]. A recent study found that the great majority of employees in the Netherlands had a strong preference to disclose MHI, as around 75% of Dutch employees indicated they had disclosed, or would want to disclose, their MHI to their manager [23, 24]. Studies have found that reasons for a disclosure preference are a positive relationship with the manager and high responsibility feelings towards the work environment [23,24,25,26,27]. However, 64% of Dutch managers were found to be reluctant to hire job applicants with MHI [13].

Rationale

Decision aids for making informed decisions about whether or not disclosing MHI in the work context seem promising [21, 28, 29]. For example, the COnceal or ReveAL (CORAL) decision aid has shown to be effective in reducing decision-making stress, and in improving work participation of unemployed people with MHI in the UK [21]. Recently, the effectiveness of CORAL in combination with a stigma awareness training for employment specialists was tested in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) in Dutch municipal practice [30]. The intervention was found to be effective for unemployed people with MHI in finding and retaining paid employment. However, in addition to investigating the effectiveness of an intervention, it is also relevant to evaluate what elements contributed to the effectiveness, and to evaluate how the intervention was implemented in practice. Therefore, in this study, a process evaluation was conducted, in order to have a better understanding of the results of the RCT and the implementation of this intervention in the future.

Aim

The aim of this process evaluation was to (1) investigate the feasibility of the stigma awareness intervention, (2) explore experiences of participants (i.e. clients and their employment specialists); and (3) give recommendations for further implementation of the stigma awareness intervention.

Method

In this mixed methods study, data for the process evaluation was gathered alongside a cluster RCT, conducted between March 2018 and July 2020. For the process evaluation, 6 process components of the framework of Linnan and Steckler [31] were used: i.e. recruitment, reach, dose delivered, dose received, fidelity and context. Quantitative and qualitative methods were used to collect data on the process components among participants of the intervention group: questionnaires for clients and employment specialists, administrative data and telephone interviews with clients and employment specialists.

Study Context

In the Netherlands, people who are above 18 years and have insufficient income or capital and who do not make use of other provisions or benefits (such as disability benefits), are entitled to social benefits. At the time of the study, 430.000–455.000 people received social benefits in the Netherlands [32]. Of the people receiving social benefits, 31% receive mental health care [33]. Taken into account the treatment gap among people with MHI [34], this is likely to be an underestimation of the actual percentage of people with MHI who receive social benefits. Receiving social benefits involves specific rights and obligations through the Work and Social Assistance Act (2004). One of these obligations is cooperating in the support municipalities offer, aimed at entering the job market or returning to existing employment. Municipalities are authorized to organize this support by themselves. As a result, some have their own vocational rehabilitation services and employment specialists who provide vocational rehabilitation to (often long-term unemployed) clients receiving social benefits from the municipality, whereas other municipalities hire the services of external organizations. The support could be organized as one-on-one appointments or as job application group training sessions to the clients.

Study Population

In the cluster RCT [30], eight organizations (i.e. municipalities and organizations who work on behalf of these municipalities) participated. Organizations were reached via the networks of the researchers. Subsequently, the researchers presented the study design during meetings at the local organizations. Randomization took place on organization level (i.e. cluster randomization). Four organizations were randomized to the intervention group and four organizations to the control group. In this study, only the organizations of the intervention group are included.

The intervention focused on 2 groups of participants: (1) unemployed people with MHI receiving social benefits, hereafter clients and (2) employment specialists working at the local municipalities who provided clients with guidance to find paid employment, hereafter employment specialists.

Clients

N = 76 clients participated in the intervention group of the study. Inclusion criteria were (1) being unemployed, i.e. an income below minimum income and receiving social benefits; (2) self-reporting to have either had a current MHI (including addiction), or to have had MHI in the past and having sought any treatment (currently or in the past) for that by a health professional (e.g. general practitioner, psychiatrist, psychologist). Type or severity of the MHI was irrelevant for inclusion in the study; and (3) adequate command of the Dutch language, as the intervention and questionnaires were in Dutch. Clients filled out questionnaires at four measurements (baseline, 3, 6 and 12 months) with questions about personal characteristics and questions regarding the feasibility of CORAL.NL (i.e. Dutch version of CORAL decision aid, see Online Appendix 1 and 4 for Dutch version and Online Appendix 2 for English version). Clients received a financial remuneration of 10 euros after filling out each questionnaire (in total clients could receive 40 euro for completing all questionnaires) to motivate them to complete the longitudinal study and to thank them for their time.

After completing the intervention study, clients of the intervention group were invited by the researchers for a telephone interview. The invited clients were a representation of the total sample in age, gender, educational level and did/did not found paid employment during the study period. N = 7 clients were not reached, other reasons for not participating in the interviews were: not interested (N = 4), too busy (N = 3), personal reasons (N = 1), and did not remember participating in the intervention study (N = 1). After interviews with N = 16 clients data saturation was reached. All signed an informed consent prior to the interview. Clients received a financial remuneration of 10 euros to thank them for their time.

Employment Specialists

Participating employment specialists were working at one of the four organizations of the intervention group, i.e. municipalities and organizations who work on behalf of municipalities. The employment specialists provided vocational rehabilitation to the clients who participated in this process evaluation and received the stigma awareness training for employment specialists, which was part of the intervention. In total, self-report data from N = 35 employment specialists was used. Employment specialists filled out questionnaires at three measurements (prior to stigma awareness training and directly and 12 months after stigma awareness training) with questions about personal characteristics and questions regarding the feasibility of the stigma awareness training and CORAL.NL.

In addition, after completing the intervention study, those employment specialists of the intervention group that who were still working at their organization (N = 13) were invited by the researchers for a telephone interview. Of them, N = 12 responded positively and signed an informed consent to participate in the interview. One employment specialist was not willing to participate in the interview.

Intervention

The stigma awareness intervention had two elements: (1) a printed booklet of the decision aid CORAL.NL for people with MHI and two infographics, i.e. simplified versions of the decision aid for those with literacy or concentration problems and (2) a 3 × 2 h training targeted at employment specialists to increase their awareness about workplace stigma. In the RCT, the control group received vocational rehabilitation without the stigma awareness intervention, i.e. practice as usual.

CORAL.NL Tool

The CORAL.NL decision aid is based on the English Conceal Or ReveAL (CORAL) decision aid [21]. The decision aid was translated and developed further into the CORAL.NL for the Dutch practice by conducting a focus group study [19]. Adjustments were related to Dutch legislation (i.e. Dutch employers are not allowed to ask questions about an employee’s illness), and by including more information about the disclosure process (i.e. who to disclose to, timing, preparation, message content and communication style) as these topics were found to be important in a previous focus group study [19]. The CORAL.NL decision aid entails a printed booklet consisting of four parts with several paragraphs: (1) choices about disclosure, including pros and cons of (non-)disclosure (e.g. ‘You can ask your employer for time off to go to things like doctor’s appointment’ and ‘You may be less likely to get the job’) and personal needs and values; (2) identifying the personal situation, including preferences about when and to whom to disclose; (3) tips (e.g. emphasize on telling what you need to do your job well rather than mentioning the mental health diagnosis, practice how to (not) disclose with a trusted one); and (4) a recap of previous sections to make a plan about whether and what to disclose or not, and if so, to whom and when. When pilot tested by employment specialists who worked with people with MHI, the CORAL.NL (a 14-pages booklet) was seen as too elaborate for people with lower concentration or reading skills. Therefore, two one-page infographics were created as a brief summary of the CORAL tool: one version about disclosure during the job application process and the other about disclosure during employment (see Online Appendix 1). The infographics consisted of three parts, including (1) reasons not to disclose MHI, (2) reasons to disclose MHI and (3) some tips about what to disclose (e.g. emphasize on telling your needs to do your job well). For the infographics, only a few items from the CORAL tool could be chosen. The selected items were confirmed to be important in a prior study on workplace mental health disclosure [19].

Stigma Awareness Training for Employment Specialists

Employment specialists participated in a stigma-awareness training about disclosure of MHI in the work context, specifically designed for the purpose of this study. While developing the training, input from a focus group study was used [19] combined with recent literature about working elements in destigmatizing interventions [35,36,37]. Important working elements are education about (people with) MHI and social contact between people with and without MHI in a context of equality [35]. Therefore, these elements were included in all training sessions. Specifically, the first training session entailed a live interview with a mental health advocate with lived experience, followed by an interactive discussion. In the second training session, a short film with personal stories of five workers with MHI who had experienced workplace stigma and discrimination was shown and discussed. In the final training session, employment specialists practiced conversations about the disclosure dilemma with a mental health advocate with lived experience. Aims of the training were enhancing awareness for (1) mental health workplace stigma and discrimination; (2) the disclosure dilemma; and (3) practice use of CORAL.NL and enhance skills for implementation. An overview of the learning goals and format of the training sessions is shown in Online Appendix 2.

The training consisted of three meetings of two hours, guided by 2–3 researchers (KJ and EB and/or MJ) and were provided in groups of 4–12 employment specialists at their own organizations. During the first meeting, employment specialists were trained to start to work with CORAL.NL in practice. In the training sessions, employment specialists were stimulated and reminded to use the CORAL.NL tool in practice, after clients had completed the baseline questionnaire.

Data Collection

Feasibility of the Intervention

To examine the feasibility of the intervention, the framework of process components by Linnan and Steckler [31] was used. The process components were described on the level of (a) clients and (b) employment specialists.

-

Recruitment: The procedures used to approach participants for the intervention. The recruitment of both clients and employment specialists was described.

-

Reach: The proportion of the intended target group that participated in the intervention. For clients, reach was defined as the proportion of those who actually participated in the study divided by the number of clients that were reached by the various recruitment strategies. For employment specialists, reach was the proportion that participated in the intervention group divided by the number of employment specialists that were invited to participate.

-

Dose delivered: The number of intended interventions that is actually delivered. In the present study dose delivered was defined for clients as the number who received the CORAL.NL tool (i.e. the booklet and infographics) by the intervention providers. For employment specialists, dose delivered is the proportion that attended the training meetings according to the protocol.

-

Dose received: The extent to which participants engaged in the intervention. For clients, dose received was defined as the proportion that (1) has read the intervention, and (2) has discussed the content of the CORAL.NL tool with their employment specialist. For employment specialists, dose received is the proportion that participated in the training meetings, and the proportion that indicated in (open) questions to actively work with the CORAL.NL tool which was introduced in the training (i.e. ‘Did you use the CORAL.NL booklet/infographics in supporting clients with MHI?’, ‘Why did you use the CORAL.NL tool?’ and ‘Do you still use the CORAL.NL tool in supporting clients with mental health issues/mental illness?’).

-

Fidelity: The extent to which the intervention was implemented and delivered as planned. For clients, fidelity was defined as the extent to which the CORAL.NL tool was implemented as planned, i.e. as a tool for clients and employment specialists to think more deliberate about disclosing MHI and/or have a conversation about the disclosure dilemma. For employment specialists, fidelity is the extent to which the training meetings were delivered as planned, and the extent to which the CORAL.NL was implemented in their support to clients. This was evaluated by self-report data from clients about their disclosure decisions and attitudes towards the CORAL.NL tool. Attitudes towards the perceived utility of the CORAL.NL tool were measured using eight statements (e.g. ‘I believe the CORAL.NL infographics were useful’, ‘The CORAL.NL tool has played an important role during the application process’ and ‘I would recommend the CORAL.NL tool to others’) with four answer categories: totally disagree, disagree, agree, totally agree. In this study, totally disagree and disagree were merged into ‘disagree’, totally agree and agree were merged into ‘agree’. In addition, data from telephone interviews with both clients and employment specialists were used.

-

Context: Aspects of the environment that may have influenced the implementation of the intervention. Both the context for clients and employment specialists will be described. The process component context was assessed by telephone interviews.

Telephone Interviews with Clients and Their Employment Specialists

Telephone interviews were held with clients and employment specialists to collect qualitative data for the process components fidelity and context. Prior to the interviews, two topic lists (one for clients and one for employment specialists) were developed based on the research questions of this study and the framework of process components [31]. The topic lists consisted of questions about experiences regarding feasibility, working elements and effects of the intervention on finding and retaining paid employment, and on what experienced barriers and facilitators were for a successful implementation. Telephone interviews lasted for about 15–30 min.

Data Analysis

Data of the questionnaires were analyzed using descriptive statistics. These statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0 for Windows. Interviews with participants were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were anonymized before analyses were performed. Interviews were coded and categorized through thematic coding by researcher KJ, using the qualitative data analysis software program Atlas.ti, version 9. Researchers EB, MJ and JW each checked the coding of two interviews (one of clients and one of employment specialists). Code agreements and disagreements were discussed within the team. Disagreements were reconsidered until agreement was reached.

Results

Mean age of clients was 37.4 years, and 58% was female. Most frequent self-reported psychiatric diagnoses were depression (26%), autism spectrum disorder (18%) and burnout (16%). For employment specialists, the mean age was 42.7 years and 84% was female. The mean years of work experience was 17.2 years, and the mean years of experience working with clients with MHI was 7.7 years (see Table 1).

Recruitment

Clients were recruited through the four participating organizations. Employment specialists personally asked eligible clients if they were willing to receive more information about the study by telephone by the researchers. However, this recruitment strategy did not ensure enough eligible clients. Therefore, eligible clients were also recruited via personal invitation letters and leaflets from the organizations where the participating employment specialists were employed. Table 2 gives an overview of the number of clients recruited via the various recruitment strategies.

Employment specialists were recruited within the four participating organizations. Two small organizations working in small teams (circa 8 employment specialists) invited all their employment specialists to participate in the study. In one large organization, the manager of a large team invited a selection of employment specialists who were not already involved in other projects or studies. In the other large organization, the manager selected the employment specialists of their team, as there were also other professionals (i.e. social workers, debt counselors) involved in their teams.

Reach

After being asked by employment specialists to be willing to receive more information about the study from the researchers, clients were contacted by telephone by the researchers to give this information, check the inclusion criteria and to invite to participate. Here, information was provided, including that their decision whether or not to participate had no consequences for their contacts with their employment specialist, and that participation was entirely on a voluntary basis and anonymous. With some recruitment strategies (e.g. personal letters), clients who did not meet the inclusion criteria (e.g. not having (had) MHI) were also recruited, but they were excluded from participating in the study. Furthermore, clients may have been recruited in two or more ways (e.g. via the employment specialist and via a personal letter). The reach percentages for the recruitment strategies were: 59/88 = 67% for personal invitations by employment specialists, 5/20 = 25% for recruitment during job application training sessions, 12/320 = 4% for invitations via personal letter or email from the organizations, and 0/0 = 0% for leaflets in waiting rooms of the organizations. The reach percentage for all recruitment strategies together was 76/428 = 18% (see Table 2).

For employment specialists, the reach percentage was 100% for two small organizations (N = 17). For one large organization, ten employment specialists were invited by their team manager to visit an information session about the research. After the sessions, eight employment specialists were willing to participate, therefore the reach percentage was 8/10 = 80%. Within the other large organization, eight employment specialists were reached by their team managers and willing to participate (8/8 = 100%). The total reach percentage was 33/35 = 94%.

Dose Delivered

All clients received the CORAL.NL booklet and infographics from the researcher after filling out the baseline questionnaire. This resulted in a dose delivered of 100%.

For employment specialists, all of them (N = 35, 100%) participated in the first training session. N = 7 employment specialists dropped out after the first training session because of several reasons: not willing to participate in the study anymore (N = 3), not working in the organization anymore (N = 3) and maternity leave (N = 1). After the second training session, N = 8 employment specialists dropped out (not working in the organization anymore: N = 7, not willing to participate in the study anymore: N = 1). In total, N = 20 employment specialists (57%) completed the full training.

Dose Received

After filling out the baseline questionnaire, clients received the CORAL.NL tool by the researchers. Although employment specialists were instructed not to hand out the tool to clients before their participation at baseline, N = 3 clients (4%) had received the tool from their employment specialist prior to baseline (data not shown in table). As can be found in Table 3, 3 months after baseline, 59% of the clients indicated in the questionnaires that they were familiar with the tool. Respectively, after 6 and 12 months, 61% and 69% of the clients were familiar with the tool. The CORAL.NL infographics had been read by 71% of the clients, and the booklet by 65% of the clients after 12 months. Around 16–18% of the clients discussed the tool with their employment specialist during the study period (see Table 3).

After completing the stigma awareness training, 68% of employment specialists indicated they had used the CORAL.NL infographics and 26% had used the CORAL.NL booklet in their contact with clients with MHI. Employment specialists who indicated they used the tool did not use these during every client contact. Of the employment specialists who used the tool (N = 13), six indicated to use them ‘because of the importance of the topic’, three ‘because clients asked questions about disclosure’ and three for other reasons. 1 year after the training, 41% reported still using the infographics and 26% the booklet. Of the employment specialists who reported using the tool, only one specialist used the tool during every client contact. Of the employment specialists who still used the tool (N = 11), one reported using them ‘because of the importance of the topic’, three ‘because clients asked questions about disclosure’ and three for other reasons (see Table 4).

Fidelity

Clients received the CORAL.NL tool, i.e. a decision aid to make more deliberate disclosure decisions in the work context, after filling out the baseline questionnaire. In case clients lost the tool or did not remember it anymore at follow-up questionnaires, the tool was provided again. In the questionnaires was found that after 12 months, 94% of the clients indicated that they believe the CORAL.NL infographic was useful, and 92% of the clients believed the CORAL.NL booklet had been useful. The CORAL.NL tool was recommended to others by 87% of the clients. For 54% of the clients the tool was helpful in deciding whether or not disclosing their MHI to an employer, and 45% indicated that the tool had changed their mind about disclosure of MHI. About one in five (22%) of the clients indicated that the tool had played an important role during their job application process and 21% indicated that the tool had been important during finding paid employment (see Table 3). In the interviews, most clients mentioned they believed that discussing the tool and the disclosure decision with their employment specialist would have been useful, although they had not discussed it.

Employment specialists were asked by managers to participate in the study. Participating in the study as employment specialist was voluntary and employment specialists filled out informed consent forms. Although the employment specialists were required by their managers to attend the training sessions, they were free to do what they wanted with the knowledge from the stigma awareness training. In addition, employment specialists were motivated but not obligated to recruit participants for the study. Employment specialists’ training sessions were provided at their organizations. If an employment specialist could not be present at a training session, a separate training session (alone or together with other employment specialists who could not be present) was organized. In the interviews, employment specialists mentioned that through the training sessions, the topic of disclosure had become more part of the conversation with clients with MHI. Employment specialists experienced more awareness about the disclosure dilemma and the everyday presence of stigmas because of the training sessions. Employment specialists mentioned to use the tool especially with clients who were actively searching for work and not to use it with clients who would deny their MHI because of having a non-Western cultural background and therefore having very different views on what MHI are, had concentration or literacy problems or were not ready to search for work yet. One of the most appreciated aspects by employment specialists was the presence of a mental health advocate with lived experience during the training sessions, which had impressed them. Furthermore, employment specialists mentioned that they had appreciated the presentations on scientific research of workplace stigma and the disclosure dilemma and the interactive debates about topic related statements, and had found these to be informative.

Context

Clients did not always have frequent meetings with their employment specialist, e.g. because employment specialists could postpone appointments in case they estimated the MHI at that moment as too severe, which hindered discussing the CORAL.NL tool with their employment specialists. In the interviews clients were asked about their opinion of the feasibility of the CORAL.NL tool. Clients found the CORAL.NL tool clear and well structured, with good explanations. Some clients mentioned that they were not yet actively seeking for a job and therefore did not see the importance of thinking whether to disclose or not. Other clients sometimes distrusted their employment specialist, thinking they were only trying to get them to work because that would save the municipality money, rather than being interested in and supportive of clients’ well-being. Facilitators mentioned for the use of the CORAL.NL tool was having a good relationship with their employment specialist and having an employment specialist who was interested in the disclosure dilemma.

In the interviews, the majority of the employment specialists mentioned that working with the tool had not become a routine and that using the tool was not necessary to discuss the disclosure dilemma with clients. However, the disclosure dilemma had become a more prominent topic of discussion in their contact with clients. They indicated that it would have helped if they would have been reminded more often to use the tool by the researchers. ‘Yes, I still have it in my mind, but it does fade away. [Also because I see a lot of clients], so it sometime [the appointments] goes quite quickly, and I notice in myself that when a lot of new things come up, certain things also recede into the background’ (Professional) In addition, employment specialists indicated that more frequent contact with the researchers and/or more training sessions could have been a facilitator to maintain focus on the disclosure topic. Employment specialists reported in the interviews that the content of the training quickly became of minor importance in their guidance of clients because of other tasks and work activities.

Previous Disclosure Experiences and Experiences Regarding Participating in the Intervention

At the baseline measurement, of the clients who had applied for work, 12% of the clients had disclosed their MHI in some job application letters, and 23% of the clients had disclosed their MHI sometimes or always during a first job application interview. After 12 months, none of the clients had disclosed their MHI in a job application letter and 19% of the clients had disclosed their MHI in a first job interview (see Table 5).

In the interviews, clients indicated that information about (non-)disclosure decisions was useful. They reported that increasing awareness of the disclosure dilemma was an important effect of the CORAL.NL tool. Clients said that as a result of the CORAL.NL tool they had become more aware of the pros and cons of both disclosure and non-disclosure. ‘Well, especially the idea of having a choice has really helped me, you know. I never really thought about it before. There’s absolutely no obligation to share those things; it’s more like… it can be helpful to share them’ (Client). In some cases, clients retained their original disclosure decision, however this decision was now more deliberate rather than intuitive only. Other clients reported that they had changed their mind after using the tool, especially from disclosure to non-disclosure but also from non-disclosure towards disclosure.

Most employment specialists were motivated to participate in the training sessions and reported that they had become more aware about stigma of MHI and the disclosure dilemma. Some of the interviewed employment specialists mentioned that they had hoped to learn more about how to deal with and support clients with MHI in their vocational rehabilitation and were somewhat disappointed that the stigma awareness intervention had not addressed this.

Discussion

The aim of this process evaluation was to investigate the feasibility of a stigma awareness intervention, to report experiences of clients and their employment specialist, and to give recommendations for further implementation in practice. The stigma awareness intervention consisted of the Dutch CORAL.NL decision aid and a newly developed stigma awareness training for employment specialists. The overall results show that the intervention was feasible to implement and that the intervention proved to be successful in increasing stigma awareness and awareness about the disclosure dilemma in both clients and their employment specialists.

The results of the study showed that the majority of the clients were positive about the content of the CORAL.NL tool. Clients affirmed they had become more aware about the importance of deliberate disclosure decisions and most of the clients would recommend the tool to others. In addition, the tool was reported to be helpful for the majority of the clients in making a decision about whether to disclose MHI or not, and 40–53% of the clients had changed their mind about disclosure of MHI due to the tool. About one in five clients indicated that the tool had helpful in applying and/or finding work. This suggests that the timing of presenting the tool to clients may be important, where it is more helpful for those people who are actively searching and/or applying for work [21]. Another explanation may be that the tool makes people feel more empowered, which may reduce self-stigma and increase someone’s self-esteem [38, 39]. Subsequently, this could lead to more positive work participation outcomes.

Results of a separately conducted RCT examining the effects of current stigma awareness intervention have shown that participants of the intervention group had found (51%) and retained (49%) paid employment twice as often compared to the control group (respectively 26% and 23%) [30]. In addition, participants of the experimental group reported to be more satisfied with the support received from their employment specialists [30]. This illustrates that it is highly important to educate and motivate employment specialists in using such interventions the tools and address the topics of stigma and disclosure with their clients. In times of high unemployment rates, which has increased only more after the COVID-19 pandemic and especially for people with MHI [40,41,42], this intervention may substantially contribute to improved employment opportunities of people with MHI, have great financial implications on a societal and personal level.

Concerning the stigma awareness training, most employment specialists adhered to completing all training sessions. Employment specialists’ opinions about the training sessions were divided. Most (teams of) employment specialists were very enthusiastic and motivated to participate in the training sessions, whilst others did not see added value. Employment specialists mainly dropped out the training sessions because of job changes. However, four employment specialists dropped out because they lost interest to participate in the study. Perhaps, this may be the result of some employment specialists’ disappointment about the content not being more broadly about how to help people with MHI. Effective elements in stigma awareness interventions are face-to-face contact with someone with lived experience and the educative components [35, 43,44,45], and these were also present in the current stigma awareness intervention and much appreciated by the employment specialists. However, in further implementation, having trainers with an employment specialist background providing the training sessions might increase participation of employment specialists because they better able to respond to the needs of employment specialists from their personal experiences.

In this process evaluation, six process components of Linnan and Steckler’s framework [31] were explored. Of all strategies, recruitment via personal invitations from employment specialists had the highest reach percentage. Other strategies (such as invitations via personal letters or email) had a lower reach percentage but were less time intensive and included in total more eligible clients. Recruitment of clients via employment specialists can cause difficulties because of keeping them involved and motivated to recruit [46]. For this reason, in this study other recruitment strategies were needed. In addition, recruitment via employment specialists could create selection bias [47], e.g. employment specialists who prevent their clients from participating or because they were unaware of the clients’ MHI because the client did not disclose.

This process evaluation has shown that the intervention was largely implemented and conducted as planned. However, the adherence to the intervention by clients and employment specialists could have been better. Low adherence to interventions is a problem in many studies (e.g. [48,49,50]), as in the current study. Around two third of the clients had read the CORAL.NL tool and one fifth of the clients had discussed the CORAL.NL tool with their employment specialists. For employment specialists, after completing the training sessions, half of them used the tool during some of their client contact. After 1 year, a quarter of the employment specialists still used it (sometimes). Improving the adherence of the intervention by clients and employment specialists in future implementation may even improve the effectiveness of the intervention on employment outcomes. Therefore, it might be helpful to systematically embed the CORAL.NL into vocational rehabilitation services. This may ensure that the tool is accessible to everyone who wants to, as the tool was not always at the forefront of employment specialists’ minds. Currently, in the Netherlands, practitioners of the supported employment method Individual Placement and Support have already incorporated the tool into their guidance.

Strengths and Limitations

A strength of this process evaluation is the use of the theoretical framework of Linnan & Steckler [31]. Using a theoretical framework ensures several relevant process components are assessed thoroughly. Second, a strength of the current study is the use of both quantitative and qualitative data, as well as the combination of data from clients together with data from their employment specialists. A limitation of this study is the lack of a fidelity instrument to measure the feasibility of the stigma awareness intervention in a structured fashion. Another limitation was the lack of information available from eligible clients who decided not to participate in the study or who were not invited by their employment specialists to participate in the study. Therefore, it was not possible to conduct a non-response analysis. The municipalities’ vocational rehabilitation services support all unemployed people in finding employment. Although people in a severe and acute phase of mental illness were not excluded from the study, they may not have been seen as eligible for the study (and/or for vocational rehabilitation) by the employment specialists. It is remarkable that in current study few clients with an anxiety disorder participated, despite the fact that the proportion of anxiety disorders among MHI is much higher, which could create bias in current study. A possible explanation may be that individuals with anxiety disorders are less inclined to participate in this type of research. Future research should determine that. In addition, a limitation of the questionnaires in this study is the use of different time points in the questions: last month, last 3 months and ever. Therefore, it is difficult to link the results of these questions to each other. Finally, in this study employment specialists were aware that they were participating in a study on improving work participation outcomes of people with MHI. This may have lead to the Hawthorne effect [51], i.e. employment specialists could have become more motivated to support people with MHI because of this extra awareness.

Implications for Research and Practice

Results of previously published RCT showed that the stigma awareness intervention was highly effective, as about twice as many clients in the experimental group found and retained paid employment after 6 (51% versus 26%) and 12 months (49% versus 23%) respectively. Moreover, clients in the intervention group were significantly more satisfied with the support received than in the control group [30]. This indicates that more attention towards MHI stigma awareness and the disclosure dilemma contributes to improved (and sustainable) labor participation and satisfaction with support from employment specialists. It is recommended that future research evaluate the effects of the intervention more specifically on changes in disclosure decisions and subsequent outcomes. The findings of current study have major implications for practice, as this suggests that as found in current study that implementing this feasible, inexpensive and relatively simple stigma awareness intervention in municipal practice, could possibly double the employment rates of unemployed people with MHI. Improving the employment outcomes of people with MHI, will both have personal positive effects, e.g. better health and wellbeing [1, 6], as well as societal benefits, such as lower societal costs. However, the findings of the current study show that many employment specialists found the tools and training not so important and that the large majority did not use the tool anymore 1 year after the trainings. Therefore, it is highly important to continue to educate employment specialists about the importance of the topic, tools and training.

Conclusion

This process evaluation showed that the implementation of a stigma awareness intervention was feasible and did increase stigma awareness in both clients and employment specialists. Experiences with the intervention were mainly positive, as 87% of the clients would recommend the CORAL.NL tool to others. Considering the intervention about doubled the number of clients who found and retained paid employment and lead to clients being more satisfied with the support received from their employment specialists [30] it is highly important to increase awareness and motivate employment specialists use the tools and address the topics of stigma and disclosure with their clients. Findings of the present study showed that the low interest employment specialists had in the topic is a concern and priority for future studies.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- RCT:

-

Randomized Controlled Trial

- CORAL:

-

Conceal or Reveal

- MHI:

-

Mental health issues/Mental illness

References

OECD. Sick on the job?: myths and realities about mental health and work. OECD Publishing Paris; 2012.

Lo CC, Cheng TC. Race, unemployment rate, and chronic mental illness: a 15-year trend analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014;49(7):1119–28.

Vaalavuo M. Deterioration in health: what is the role of unemployment and poverty? Scan J Pub Health. 2016;44(4):347–53.

Zechmann A, Paul KI. Why do individuals suffer during unemployment? Analyzing the role of deprived psychological needs in a six-wave longitudinal study. J Occup Health Psychol. 2019;24(6):641.

Hampson ME, Watt BD, Hicks RE. Impacts of stigma and discrimination in the workplace on people living with psychosis. BMC Psychiat. 2020;20(1):288.

van der Noordt M, H IJ, Droomers M, Proper KI. Health effects of employment: a systematic review of prospective studies. Occup Environ Med. 2014;71(10):730–6.

Brouwers EPM. Social stigma is an underestimated contributing factor to unemployment in people with mental illness or mental health issues: position paper and future directions. BMC Psychol. 2020;8:1–7.

Brouwers EP, Mathijssen J, Van Bortel T, Knifton L, Wahlbeck K, Van Audenhove C, et al. Discrimination in the workplace, reported by people with major depressive disorder: a cross-sectional study in 35 countries. BMJ open. 2016;6(2):e009961.

Stuart H. Mental illness and employment discrimination. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2006;19(5):522–6.

Russinova Z, Griffin S, Bloch P, Wewiorski NJ, Rosoklija I. Workplace prejudice and discrimination toward individuals with mental illnesses. J Voc Rehabil. 2011;35(3):227–41.

Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Ann Rev Sociol. 2001;27(1):363–85.

van Beukering IE, Smits SJC, Janssens KME, Bogaers RI, Joosen MCW, Bakker M, et al. In what ways does health related stigma affect sustainable employment and well-being at work? A systematic review. J Occup Rehabil. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-021-09998-z.

Janssens KME, van Weeghel J, Dewa C, Henderson C, Mathijssen JJP, Joosen MCW, et al. Line managers’ hiring intentions regarding people with mental health problems: a cross-sectional study on workplace stigma. Occup Environ Med. 2021;78(8):593.

Biggs D, Hovey N, Tyson PJ, MacDonald S. Employer and employment agency attitudes towards employing individuals with mental health needs. J Men Health. 2010;19(6):505–16.

Henderson C, Williams P, Little K, Thornicroft G. Mental health problems in the workplace: changes in employers’ knowledge, attitudes and practices in England 2006–2010. Br J Psychiat. 2013;202(s55):s70–6.

Lettieri A, Díez E, Soto-Pérez F. Prejudice and work discrimination: exploring the effects of employers’ work experience, contact and attitudes on the intention to hire people with mental illness. T Soc Scien J. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/03623319.2021.1954464.

Lettieri A, Díez E, Soto-Pérez F, Bernate-Navarro M. Employment related barriers and facilitators for people with psychiatric disabilities in Spain. Work. 2022;71:901–15.

Corrigan PW, Larson JE, Rusch N. Self-stigma and the why try effect: impact on life goals and evidence-based practices. W Psychiat. 2009;8(2):75–81.

Brouwers EPM, Joosen MCW, van Zelst C, Van Weeghel J. To disclose or not to disclose: a multi-stakeholder focus group study on mental health issues in the work environment. J Occup Rehabil. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-019-09848-z.

Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Waldmann T, Staiger T, Bahemann A, Oexle N, et al. Attitudes toward disclosing a mental health problem and reemployment: a longitudinal study. The J Ner Men Diseas. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000810.

Henderson C, Brohan E, Clement S, Williams P, Lassman F, Schauman O, et al. Decision aid on disclosure of mental health status to an employer: feasibility and outcomes of a randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;203(5):350–7.

Toth KE, Dewa CS. Employee decision-making about disclosure of a mental disorder at work. J Occup Rehabil. 2014;24(4):732–46.

Dewa CS, Van Weeghel J, Joosen MC, Brouwers EP. What could influence workers’ decisions to disclose a mental illness at work? Int J Occup Environ Med. 2020;11(3):119.

Dewa CS, van Weeghel J, Joosen MC, Gronholm PC, Brouwers EP. Workers’ decisions to disclose a mental health issue to managers and the consequences. Fron Psychiat. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.631032.

Dewa C. Worker attitudes towards mental health problems and disclosure. Int J Occup Environ Med. 2014;5(4):175.

Evans-Lacko S, Knapp M. Global patterns of workplace productivity for people with depression: absenteeism and presenteeism costs across eight diverse countries. Soc Psychiat and Psychiatr Epidem. 2016;51:1525–37.

Von Schrader S, Malzer V, Bruyère S. Perspectives on disability disclosure: the importance of employer practices and workplace climate. Empl Respons Rights J. 2014;26:237–55.

Stratton E, Choi I, Hickie I, Henderson C, Harvey SB, Glozier N. Web-based decision aid tool for disclosure of a mental health condition in the workplace: a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med. 2019;76(9):595–602.

McGahey E, Waghorn G, Lloyd C, Morrissey S, Williams PL. Formal plan for self-disclosure enhances supported employment outcomes among young people with severe mental illness. Early Interv Psychia. 2016;10(2):178–85.

Janssens KME, Joosen MCW, Henderson C, Bakker M, van Weeghel J, Brouwers EPM. Effectiveness of a stigma awareness intervention on reemployment of people with mental health issues/ mental illness: a cluster randomised controlled trial. J Occup Rehabil. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-023-10129-z.

Steckler AB, Linnan L, Israel B. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002.

Statistics Netherlands. Persons with social benefits; personal characteristics (Personen met bijstand; persoonskenmerken). Den Haag: Statistics Netherlands. Available from: https://opendata.cbs.nl/#/CBS/nl/dataset/82016NED/table?dl=927A5 (2023).

Einerhand M, Ravesteijn B. Psychische klachten en de arbeidsmarkt. Gezondheidszorg. 2017;102(4754):3.

Evans-Lacko S, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Benjet C, Bruffaerts R, et al. Socio-economic variations in the mental health treatment gap for people with anxiety, mood, and substance use disorders: results from the WHO World Mental Health (WMH) surveys. Psychol Med. 2018;48(9):1560–71.

Thornicroft G, Mehta N, Clement S, Evans-Lacko S, Doherty M, Rose D, et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental-health-related stigma and discrimination. Lancet. 2016;387(10023):1123–32.

Gronholm PC, Henderson C, Deb T, Thornicroft G. Interventions to reduce discrimination and stigma: the state of the art. Soc Psychiat and Psychiatr Epidem. 2017;52(3):249–58.

Gayed A, Milligan-Saville JS, Nicholas J, Bryan BT, LaMontagne AD, Milner A, et al. Effectiveness of training workplace managers to understand and support the mental health needs of employees: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Occup Environ Med. 2018;75(6):462.

Mittal D, Sullivan G, Chekuri L, Allee E, Corrigan PW. Empirical studies of self-stigma reduction strategies: a critical review of the literature. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63(10):974–81.

Yanos PT, Lucksted A, Drapalski AL, Roe D, Lysaker P. Interventions targeting mental health self-stigma: a review and comparison. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2015;38(2):171.

Petrosky-Nadeau N, Valletta RG. An unemployment crisis after the onset of COVID-19. FRBSF Economic Letter. 2020;12:1–5.

Şahin A, Tasci M, Yan J. The unemployment cost of COVID-19: how high and how long? Econ Comm. 2020. https://doi.org/10.26509/frbc-ec-202009.

Pompili M, Innamorati M, Sampogna G, Albert U, Carmassi C, Carrà G, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on unemployment across Italy: consequences for those affected by psychiatric conditions. J Affect Dis. 2022;296:59–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.035.

Pinfold V, Thornicroft G, Huxley P, Farmer P. Active ingredients in anti-stigma programmes in mental health. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2005;17(2):123–31.

Hanisch SE, Twomey CD, Szeto ACH, Birner UW, Nowak D, Sabariego C. The effectiveness of interventions targeting the stigma of mental illness at the workplace: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16(1):1.

Mehta N, Clement S, Marcus E, Stona A-C, Bezborodovs N, Evans-Lacko S, et al. Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental health-related stigma and discrimination in the medium and long term: systematic review. Br J Psychiatr. 2015;207(5):377–84.

Howard L, de Salis I, Tomlin Z, Thornicroft G, Donovan J. Why is recruitment to trials difficult? An investigation into recruitment difficulties in an RCT of supported employment in patients with severe mental illness. Contemp Clin Trials. 2009;30(1):40–6.

Kahan BC, Rehal S, Cro S. Risk of selection bias in randomised trials. Trials. 2015;16:405.

Volker D, Zijlstra-Vlasveld MC, Brouwers EPM, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM. Process evaluation of a blended web-based intervention on return to work for sick-listed employees with common mental health problems in the occupational health setting. J Occup Rehabil. 2017;27(2):186–94.

Joosen MCW, van Beurden KM, Terluin B, van Weeghel J, Brouwers EPM, van der Klink JJL. Improving occupational physicians’ adherence to a practice guideline: feasibility and impact of a tailored implementation strategy. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):82.

Joosen MCW, van Beurden KM, Rebergen DS, Loo MAJM, Terluin B, van Weeghel J, et al. Effectiveness of a tailored implementation strategy to improve adherence to a guideline on mental health problems in occupational health care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19(1):281.

McCambridge J, Witton J, Elbourne DR. Systematic review of the Hawthorne Effect: new concepts are needed to study research participation effects. J of Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(3):267–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.015

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants from the research program Vakkundig aan het Werk of The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Grant Number: 535001003). We thank all participants and participating municipalities and organizations, including the employment specialists who participated in this study. We thank the client advisory board for advising us about recruiting participants. We thank the student-assistants for their help in data collection.

Funding

This study was funded by grants from the research program Vakkundig aan het Werk of The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Grant Number: 535001003).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EB, MJ, JW and KJ: designed the study and developed the Dutch intervention. CH: was involved by developing the Dutch intervention. Project supervision is provided by EB, MJ and JW. KJ: drafted the first version of the article. EB, MJ, JW, and CH: provided feedback on the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and no professional writer has been involved.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

KJ, MJ, CH, JW and EB declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. The Ethics Review Board of Tilburg University evaluated and approved the study design, protocol, information letter, informed consent form and questionnaires (EC-2018.06t). The study was registered at the Dutch Trial Register under trial registration number NL7798.

Consent to Participants

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable (no case reports or images/figures of individual participants).

Informed Consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Janssens, K.M.E., Joosen, M.C.W., Henderson, C. et al. Improving Work Participation Outcomes Among Unemployed People with Mental Health Issues/Mental Illness: Feasibility of a Stigma Awareness Intervention. J Occup Rehabil 34, 447–460 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-023-10141-3

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-023-10141-3