Abstract

Purpose The sustainable employability of healthcare professionals in aged care is under pressure, but research into the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving employees’ sustainable employability is scarce. This review therefore aimed to investigate the effectiveness of workplace interventions on sustainable employability of healthcare professionals in aged care. Methods A systematic literature search was performed. Studies were included when reporting about the effect of an intervention at work in an aged care setting on outcomes related to one of the three components of sustainable employability (i.e. workability, vitality, employability). The methodological quality of each study was assessed and a rating system was used to determine the level of evidence. Additionally, a sensitivity analysis was performed, accounting for the match between the intervention’s focus and the targeted component of sustainable employability. Results Current review includes 32 interventions published between 1996 and 2019. Interventions covered learning and improving skills, changing the workplace, and exercising or resting. The initial analysis showed a strong level of evidence for employability and insufficient evidence for workability and vitality. The sensitivity analysis revealed strong evidence for the effectiveness of interventions addressing either employability or workability, and insufficient evidence for vitality. Conclusions Evidence for workplace interventions on sustainable employability of healthcare professionals in aged care differed. We found strong evidence for effects of workplace interventions on employability and for those directly targeting workability. Evidence for effects of interventions on vitality was insufficient. The alignment of the interventions to the targeted component of sustainable employability is important for effectiveness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Retaining healthcare professionals in aged care for their profession is an important yet challenging task nowadays. While the aging population increases the demand for care for older adults, the number of caregivers relative to older people has stagnated in most countries since 2011 [1]. This stagnation originates from the difficulty to attract young people and the challenge to retain current staff [1]. Job characteristics, like low compensation, high physical and emotional demands, heavy workload, scheduling challenges, insufficient supervision and limited training and career advancement prospects are related to job dissatisfaction and high turnover [2,3,4,5,6], which reinforces the difficulties for those remaining in the job [1, 7,8,9,10].

With many staff leaving the profession, sustainable employability of the workforce is a growing concern [11]. Sustainable employability has been defined by van der Klink et al. [12] as opportunities and conditions needed for employees to ‘make a valuable contribution through their work, now and in the future, while safeguarding their health and welfare’ (p. 74). In scholarly literature, three components have been distinguished to reflect an individual’s sustainable employability, i.e. workability, vitality and employability [13,14,15]. Workability has been described as the physical, mental and social capacity needed to deal with work demands [16]. Workability is therefore closely related to health, which is not limited to the absence of disease but refers to a complete state of physical, mental and social wellbeing [17]. Vitality has been defined as experiencing levels of energy and motivation [15], as being intrinsically motivated [18], and also as a state of both high psychological well-being and physical health [19]. Employability refers to the ability to adequately perform various tasks and to function optimally at work, now and in the future [15]. Taken together, workability mainly focuses on the health and functional capacity of employees, vitality mostly concerns energy and motivation, and employability focuses on employees’ knowledge and competences [20].

Given the growing general interest in sustainable employability, it is not surprising that previous reviews have attempted to shed light on the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving sustainable employability of employees. These reviews show that there (a) is insufficient evidence for the effectiveness of interventions on measures of sustainable employability specifically among aging employees [21], (b) is moderate-quality evidence for the effectiveness of workplace interventions on workability [22], and (c) are significant positive effects in a minority of interventions when aimed at the capabilities of an employee, i.e. employability [23]. Methodological limitations like small sample sizes and/or lack of high quality interventions hamper definite conclusions about the effectiveness of these interventions [21, 23].

From these previous reviews it is still unclear what effects interventions could have on the broad spectrum of sustainable employability (i.e., workability, vitality and employability), and for healthcare professionals caring for older adults in particular. Even more so because included interventions are mostly directed at the individual level. Interventions implemented on team- or organisational level might be more promising, since comprehensive interventions on all levels of the organisation are amongst the most effective to change wellbeing inhibiting factors at work [24]. Workplace interventions on the team- or organisational level seem to be especially promising in health care, where trust in management and teamwork appear to contribute to sustainable employability over time [11]. There is also the additional benefit of reaching larger groups of employees with team- or organisational level interventions [25].

Organisations providing care for older adults are urgently looking for ways to improve the sustainable employability of their staff. However, they lack an integrative overview of effective interventions to make evidence-based decisions. The present systematic review aims to contribute to a better understanding of the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving sustainable employability by a) incorporating a broad conceptualisation of sustainable employability that includes all three components (workability, vitality and employability), b) including interventions at the team- and organisational level (referred to as workplace interventions), and c) tailoring the search to a sector which is specifically in need of a sustainable workforce, namely aged care. Our review will not only shed more light on the effectiveness of workplace level interventions aimed at improving sustainable employability, but will also guide organisations providing care for older adults in their search towards an approach to attain a sustainable workforce that is so highly needed, now and in the future.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review guided by the principles of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [26]. We registered the review protocol in the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO ID:161,999).

Search Strategy

Together with an information specialist we designed our search strategy that involved searches in five databases: Embase, CINAHL, Medline, PsycINFO, and Web of Science. Our search strategy consisted of keywords related to the population of interest (e.g. caregivers, care providers or nurses), the setting (e.g. long-term care, elderly care), the context (e.g. workplace or job), the intervention (e.g. intervention, training or program) and design (e.g. controlled study or randomised controlled trial). We did not specify keywords related to outcomes, because we aimed to include a broad range of outcome measures related to our operationalisation of sustainable employability. The search was restricted to English language journal articles and covered all articles available at the time of the literature search (January 20th 2020). The full search strategy can be found in the supplementary materials.

Operationalisation of Sustainable Employability

In this study we define an individual’s sustainable employability according to three components, i.e. workability, vitality and employability [14, 15, 27]. Conceptually there is some overlap between the three components, especially between vitality and workability. Both workability and vitality have been described in terms of psychological well-being and physical health [16, 19]. In order to better distinguish between the three components of sustainable employability in this review, we define workability in terms of physical health and functional capacity of employees, vitality in terms of mental health, energy and motivation, and employability in terms of employees’ knowledge and competences [20]. We made a distinction between physical health (workability) and mental health (vitality), since the latter has a closer relationship with mental processes like feeling energetic and intrinsically motivated [18, 28]. Table 1 shows our operationalisation of the three components and corresponding example outcome measures.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion in this review if they evaluated an intervention at work that targeted one or more outcomes related to one or more components of healthcare professionals’ sustainable employability. Because we were interested in workplace interventions that were implemented on the team- or organisational level, interventions focusing on individuals, as well as national or governmental policy were excluded. The intervention should have been implemented in a setting in which older people (often called ‘residents’) live or are taken care of (e.g. nursing homes, dementia special care units or home care). The study had to report on outcomes measures related to workability, vitality and/or employability of the care staff. In terms of design we included studies that were randomised or non-randomised controlled trials reporting at least two time points (pre- and post-intervention). The analytical strategy had to take into account the effect of group over time (e.g. interaction effect or adjusting for baseline value of outcome measure). Only primary quantitative studies were eligible for inclusion; qualitative studies, meta-analyses or theoretical papers were excluded.

Study Selection

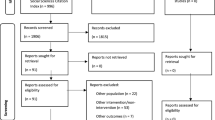

An overview of the study selection based on the PRISMA flow diagram [29] is depicted in Fig. 1. After a first draw from the databases, all duplicates were removed. Next, the first and second author used Rayyan [30], an online tool for systematic reviews, to assess titles and abstracts of the remaining studies based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. After screening 20 percent of the studies, there was no more than 5 percent disagreement between the first and second author about selection of the full-text paper. The first author continued to screen the remaining titles and abstracts and discussed any doubts with the second author. For the titles and abstracts that were selected for full-text appraisal, full-text copies were retrieved, which were assessed by the two authors independently. In case of a disagreement, the third and fifth author were consulted for a final decision. The first author screened the bibliography and identified 10 additional studies of interest. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria the first and second author agreed to include five more studies from the bibliography search, resulting in a total of 33 studies included in the synthesis.

Data Extraction

A custom made data-extraction form was used to extract the following data per study: author, publication year and country, study population, study design, intervention, outcome measures, significance and direction of relationships. Study outcomes were categorized into workability, vitality and employability. Results on outcome measures that did not fit into one of the three components of sustainable employability were not extracted (e.g. resident outcomes, training evaluations). The first and second author extracted the data of five articles together, after which the first author continued the extraction. The second author, and in some instances other authors, was involved in cases of uncertainty about the extracted data.

Quality Assessment

The methodological quality of the included studies was independently assessed by the first two authors by means of the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project [31]. This tool is suitable for the assessment of both randomised and non-randomised studies and has been used previously in other (review) studies [23, 32, 33]. The tool consists of six sections: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawals and dropouts. Each section was assessed as ‘strong’, ‘moderate’ or ‘weak’, in consonance with the tool’s dictionary. The overall quality of the studies was either strong (i.e. no weak sections), moderate (i.e. one weak section) or weak (i.e. two or more weak sections). Any discrepancies within ratings of the two reviewers were discussed in order to reach consensus.

Level of Evidence Rating

To our knowledge there is no existing level of evidence scheme that takes into account heterogeneity of outcome measures within single studies and heterogeneity of outcome measures within overarching components. Before we could apply an already existing rating system by Hoogendoorn et al. [34] and Van Drongelen et al. [35], we had to conduct two additional steps as this rating system does not take into account the possibility that one study contains multiple outcomes. Because we postulated these steps post-hoc, they were not included in the preregistration.

First, we looked at the statistical significance and direction of the relationships found within a study. If 50 percent or more of the outcome measures within a study were statistically significantly impacted in the same direction (p < 0.05), this was noted as ‘statistically significant impact’ in the data extraction table. This could be either a positive or negative statistical significance in relation to the component of sustainable employability at hand. If less than 50 percent of the outcomes were statistically significantly impacted, this was noted as ‘no statistically significant impact’ for that particular study on the component of sustainable employability. As most of the articles had 1, 2 or 3 outcome measures per component of sustainable employability, the 50 percent cut-off score was chosen because it yields the right balance without being too strict or too lenient in deciding upon the statistical impact of an intervention.

Subsequently, we looked at the consistency of the statistical significance and the direction of the relationships found across studies on the level of each component of sustainable employability. Here we used the cut-off score by Hoogendoorn’s et al. [34] and Van Drongelen’s et al. [35] rating scheme stating there is ‘insufficient evidence’ for an effect if less than 75 percent of the studies within a component of sustainable employability has been evaluated as having a statistically significant impact in the same direction. If this percentage is (more than) 75 percent, the findings are considered ‘consistent’.

In the last step we rated every component of sustainable employability by the scheme of by Hoogendoorn et al. [34] and Van Drongelen et al. [35] including the quality assessment rating for a final decision on evidence. The level of evidence was therefore either ‘strong’ (consistent findings in multiple high-quality studies), ‘moderate’ (consistent findings in one high-quality and/or multiple moderate-quality studies) or ‘insufficient’ (only one study available or inconsistent findings in multiple studies).

In addition, a sensitivity analysis was performed, in which we repeated the steps described above, but only including interventions directly addressing the component of sustainable employability. We have postulated this sensitivity analysis post-hoc, because we noted during data extraction that alignment between the intervention and outcome measures was not self-evident. As such, this analysis was not included in the preregistration.

Results

A total of 33 controlled trials published between 1996 and 2019 were included in the synthesis. Two articles reported about the same intervention [36, 37], which resulted in 32 unique interventions. Studies took place in several parts of the world (i.e. Europe, Australia, USA, Asia). Seventeen interventions focused on care-related education (e.g. person-centred care, oral health care or care with minimal restraints). Ten interventions mainly focused on skills (e.g. communication skills, feeding skills, dealing with challenging behaviours). Two programs aimed at changing the workplace (e.g. work improvement or redesign, implementing ceiling lifts) and three interventions involved physical activity or resting periods for the employees (e.g. exercising or a relaxing foot massage during work). Six studies consisted of one session, all the other studies included several sessions over the course of multiple weeks or months. Table 2 shows characteristics and results of the included studies, categorized by the outcome measure of interest matching the component of sustainable employability.

Quality Assessment

The overall methodological quality of the studies varied from weak, to moderate and strong (Table 3). Twelve studies were rated as strong, twelve as moderate and nine as weak. Since our review only included studies with a control group, all studies were designed either as a randomised controlled trial or a controlled trial (without randomisation) and were therefore rated ‘strong’ with respect to the quality of their study design. All studies received a moderate rating on the category blinding, because most studies did not provide information on the outcome assessor(s) and participants’ awareness of relevant blinding issues (e.g. exposure status of the participant or the awareness of the research question). Indistinct reporting on withdrawals, dropouts, and validity and reliability of data collection tools, was for most studies reason for their overall weak quality rating.

Effectiveness on Workability Outcomes

Seven studies reported about outcomes related to workability, such as skin symptoms, lower back pain or global physical impairment. Five out of seven interventions had a statistically significant positive impact on outcomes related to workability, meaning that within these five studies 50 percent or more of the outcome measures showed a statistically significant positive impact (p < 0.05). Those were interventions with a focus on employees’ physical health, namely a skin care program [38], the use of overhead ceiling lift program to prevent injury [39], a foot massage to improve blood pressure [40], an exercise program to improve physical health [41], and a multifaceted intervention including participatory ergonomics, cognitive behaviour training and physical training to prevent lower back pain [42]. The two interventions showing no statistically significant impact were mainly focused on improving employees’ skills, and encompassed a training in dementia care [43] and an acceptance and commitment therapy intervention [44].

When taking all the studies into account, less than 75 percent of the studies (5 out of 7, 71%) showed statistically significant results in the same (positive) direction, resulting in an overall rating of insufficient evidence. The sensitivity analysis, only including interventions directly addressing physical health and functional capacities of employees, revealed that all studies (5 out of 5, 100%) showed a statistically significant positive impact in multiple strong/moderate quality studies. According to the sensitivity analysis there is strong level of evidence for the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving outcomes related to workability of aged care staff.

Effectiveness on Vitality Outcomes

More than half of the included studies in this review (19 of the 32), reported about outcomes related to vitality. Levels of burnout (i.e. emotional exhaustion, personal accomplishment and depersonalisation) and satisfaction were amongst the most frequently assessed outcomes, and were incorporated in fourteen studies. Only four studies showed a statistically significant positive impact on outcomes related to vitality, meaning that within these four studies 50 percent or more of the outcome measures showed a statistically significant positive impact (p < 0.05). One of them was a relaxing foot massage [40] and the other three were interventions targeting skills of the employee, i.e., an emotion regulation training [45], an acceptance and commitment therapy intervention [44], and a train-the-trainer in dementia care intervention [46]. The interventions that showed no statistically significant impact on increasing vitality were interventions focusing on education about person-centred care, geriatric nursing, communication, challenging behaviours, cooperation and emotion oriented care [36, 37, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53]. Other interventions with no statistically significant impact focused on skills (positive psychology, dealing with people with dementia, self-efficacy, cooperation and communication or experiencing degenerating physical functioning) or included a change in the workplace (instalment of ceiling lifts and job redesign) [39, 43, 54,55,56,57,58]. As less than 75 percent of the studies (4 out of 19, 21%) showed statistically significant results in the same direction, the level of evidence for vitality is rated as insufficient. For the sensitivity analysis we included three studies directly addressing the energy and motivation of employees themselves, which where the emotion regulation training, the positive psychology intervention and the acceptance and commitment therapy [44, 45, 54]. The sensitivity analysis revealed that 2 out of 3 studies (67%) showed a statistically significant impact, whereby indicating that the level of evidence for the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving vitality of aged care staff is insufficient.

Effectiveness on Employability Outcomes

Over half of the included studies in this review (17 out of 32) reported about outcomes related to employability. Knowledge is the most frequently reported outcome regarding this component, and is measured in fourteen studies. Fourteen interventions showed a statistically significant positive impact on outcomes related to employability, meaning that within these fourteen studies 50 percent or more of the outcome measures showed a statistically significant positive impact (p < 0.05). These interventions all focused on improving knowledge and/or skills of the employee (e.g. oral health care, restraint reduction, communication, dealing with challenging behaviour, self-efficacy) [43, 46, 48, 49, 56, 58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66].

Since more than 75 percent of the studies (14 out of 17, 82%) showed statistically significant results in the same (positive) direction and multiple were of high quality (5 strong and 5 moderate quality studies), the level of evidence is rated as strong. Since all studies had a clear link to the competence and skills of employees, no additional sensitivity analysis was conducted.

Discussion

This review aimed to investigate the effectiveness of workplace interventions at team- or organisational workplace level on each of the three components (i.e,. workability, vitality, employability) of sustainable employability of healthcare professionals caring for older adults. We found strong level of evidence for effects of workplace interventions on employability and for workplace interventions directly targeting workability. Evidence for effects of interventions on vitality was insufficient.

Regarding workability, it is remarkable that we did not find strong evidence for the effectiveness of interventions when taking all interventions into account. However, we did find strong level of evidence when only taking into account interventions directly addressing workability. All interventions with a statistically significant positive impact had a direct link to the core of our operationalisation of workability, namely the physical health of employees. In contrast, interventions that did not have a direct link to physical health of the employee (i.e. dementia care and acceptance and commitment therapy) did not report a statistically significant impact on workability. The reviews by Oakman et al. [22] and Cloostermans et al. [21] also found no effect of interventions targeting behaviour change through education on workability. In contrast to our findings, they also did not find an impact of physical activity interventions on workability. Since our review included indicators of workability (and not workability itself), the effects in our review were possibly more direct and short-term effects of the interventions. Future research should disentangle whether these effects on indicators of workability also have a significant and enduring impact over time.

The results concerning outcomes related to vitality show a more complicated picture. Very few studies had a statistically significant impact on outcomes related to the vitality of employees. The interventions with statistically significant impact varied in terms of approach, content and outcome measures. One of them was a relaxing foot massage [40] and the other three were interventions in which very different kinds of skills of the employee were targeted, such as emotion regulation [45], acceptance and commitment/mindfulness [44], and skills to train others in dementia care [46]. The level of evidence for the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving vitality of healthcare professionals in aged care was rated insufficient. This result is in line with the return-to-work literature showing insufficient and mixed evidence for workplace interventions on outcomes related to quality-of-life (e.g. mental health) [67]. What stands out in our review is that almost all studies on vitality without statistically significant impact were primarily aimed at improving the workplace or knowledge/skills of the employee and expected outcomes related to vitality to be the secondary/indirect effect of the intervention [36, 37, 39, 43, 47,48,49,50,51,52,53, 55, 57, 58]. To illustrate, an educational intervention can be effective in improving skills (employability), but rarely has an additional impact on employee well-being or stress (vitality) [46, 48]. It could be that interventions aimed at vitality are more often focused on the individual and therefore not included in this review. Nonetheless, our finding is congruent with the review of Hazelzet et al. [23] who suggested that the misalignment of the outcome measures and intervention content explains the limited evidence for effectiveness of the interventions. In order to attain effects of workplace interventions at the vitality of employees it thus seems important that the interventions focuses on that component specifically. To draw conclusions about the effectiveness of interventions on outcomes of vitality, future research should dive into the success factors of the few successful current interventions. Effect- and process evaluations of new workplace interventions aiming to improve the energy and motivation of staff should provide insight into the effectiveness of these vitality-directed interventions.

Our finding of strong level of evidence for the effectiveness of interventions on outcomes of employability is in line with the review of Hazelzet et al. [23] showing that interventions can have positive effects when aimed at having the right competences to perform the job, and development of skills and knowledge. In our review we found that almost all interventions focused on improving knowledge and/or skills of employees showed statistically significant impact in doing so, which is in agreement with the predominantly effective educational initiatives in several topics in nursing care [68, 69].

Methodological Considerations

For our literature search we used a very thorough search strategy that was developed with an experienced librarian. On the one hand we searched for well-designed studies (with both pre-post measures and a control group) in a specific target population (healthcare professionals caring for older adults) with broad outcome measures (related to sustainable employability). Our search therefore resulted in a rich sample of interventions, in which we exclusively focused on outcomes that we considered indicative of sustainable employability according to the classification as described by De Vos and Van der Heijden [20]. The decision to consider a certain outcome as an indicator of workability, vitality or employability was to some extent subjective, since there is no consensus among scholars about the definition and components of sustainable employability [20, 70].

On the other hand, our search strategy led to heterogeneity in outcomes related to a component of sustainable employability. As a result, specific information about the methods and effects of single studies are lost in general statements about the effectiveness of interventions on the level of the components of sustainable employability. For example, we did not differentiate between studies with long and short-term follow-up, online versus offline interventions, or interventions including one or multiple sessions. Since the review focused on effect evaluations, and not on process evaluations, it is unknown whether the lack of evidence for components of sustainable employability were either due to program failure or theory failure [71].

The diversity of the sample is also visible in the quality assessments. The quality of the included articles varied from weak, to moderate, to strong. In order to be rated as ‘strong’ on the data collection component of the quality assessment tool, studies had to provide information about the validity of the measures that were incorporated. Not all articles included this information, resulting in an immediate weak score on this component.

To assess the level of evidence, we have postulated a sensitivity analysis post-hoc, because we noted during data extraction that the alignment between the intervention and outcome measures differed between studies. This additional analysis enabled us to show that the link between the intervention and outcome is an important factor in the level of evidence for effectiveness of the interventions.

The overall level of evidence rating scheme is based on the previously used scheme by Hoogendoorn et al. [34] and Van Drongelen et al. [35], which involves the counting of effective studies versus ineffective studies based on their attained outcome measures’ p-value. With this method a nonsignificant finding could be due to a true absence of the effect, but it can also be due to low statistical power [72]. Also, p-values do not state anything about the size or clinical relevance of effects, since statistical significance does not necessarily imply large or meaningful effects [73]. The used method therefore provides more insight into the level of evidence for effectiveness of interventions on components of sustainable employability, rather than referring to the size or clinical relevance of the findings. Effect sizes that were reported in the full-texts of the studies varied from small, to medium and large [40, 43,44,45, 48].

Practical Implications and Recommendations for Future Research

As a result of this review, we have a number of recommendations for facilities providing care for older adults, if they wish to improve employees’ sustainable employability. Firstly, we would advise these facilities to prioritize one component of sustainable employability within their organisation, because to date we have no (evaluated) interventions that show statistically significant positive effects on all three of its components. Secondly, it is important that organisations look for an intervention that matches the component they intend to improve. For workability this means that interventions should focus on the physical health and functional capacities of employees and for employability the main focus should lie on development of knowledge and skills. Our review does not offer much evidence for the effectiveness of workplace vitality-directed interventions. Therefore, future research should focus on evaluation of interventions aimed at improving the energy and motivation of employees at team or organisational level as this will enable us to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of such interventions on vitality.

Concluding Remarks

We found different levels of evidence for workplace interventions on sustainable employability of aged care staff. We found a strong level of evidence for—small to large sized—effects of workplace interventions on employability and for workplace interventions directly targeting workability. For workability this means that interventions should focus at the physical health and functional capacities of employees and for employability the main focus should lie on the development of knowledge and skills. Evidence for effects of interventions on vitality was insufficient. More research is needed towards workplace interventions aimed at improving vitality to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of such interventions on vitality. This is necessary because of the focus of workplace interventions to the component of the sustainable employability it is aiming to improve, is important for its effectiveness.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

OECD. Who Cares? Attracting and Retaining Elderly Care Workers [Internet]. OECD; 2020. [cited 2020 Dec 3] (OECD Health Policy Studies). https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/social-issues-migration-health/who-cares-attracting-and-retaining-elderly-care-workers_92c0ef68-en

Brannon D, Barry T, Kemper P, Schreiner A, Vasey J. Job perceptions and intent to leave among direct care workers: evidence from the better jobs better care demonstrations. Gerontol. 2007;47(6):820–9.

Ejaz FK, Noelker LS, Menne HL, Bagaka’s JG. The impact of stress and support on direct care workers job satisfaction. Gerontol. 2008;48(Suppl 1):60–70.

Franzosa E, Tsui EK, Baron S. “Who’s caring for us?”: understanding and addressing the effects of emotional labor on home health aides’ well-being. Gerontol. 2019;59(6):1055–64.

Kemper P, Heier B, Barry T, Brannon D, Angelelli J, Vasey J, et al. What do direct care workers say would improve their jobs? Differences Across Settings. Gerontol. 2008;48(suppl 1):17–25.

Stone R, Wilhelm J, Bishop CE, Bryant NS, Hermer L, Squillace MR. Predictors of intent to leave the job among home health workers: analysis of the national home health aide survey. Gerontol. 2016;57(5):890–9.

Cooke FL, Bartram T. Guest editors’ introduction: human resource management in health care and elderly care: current challenges and toward a research agenda. Hum Resour Manage. 2015;54(5):711–35.

Estryn-Béhar M, Nézet OL, Van der Heijden BIJM, Ogińska H, Camerino HM, Conway PM, et al. Inadequate teamwork and burnout as predictors of intent to leave nursing according to seniority stability of associations in a one-year interval in the European NEXT Study. Ergon Int J Ergon Human Fact. 2007;29(3–4):225–33.

Jourdain G, Chênevert D. Job demands–resources, burnout and intention to leave the nursing profession: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2010;47(6):709–22.

Poghosyan L, Clarke SP, Finlayson M, Aiken LH. Nurse burnout and quality of care: cross-national investigation in six countries. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(4):288–98.

Roczniewska M, Richter A, Hasson H, von Schwarz UT. Predicting sustainable employability in Swedish healthcare the complexity of social job resources. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(4):1200.

Van der Klink JJ, Bültmann U, Burdorf A, Schaufeli WB, Zijlstra FR, Abma FI, et al. Sustainable employability—definition, conceptualization, and implications: a perspective based on the capability approach. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2016;42(1):71–9.

De Lange AH, Van der Heijden BIJM. Een leven lang inzetbaar? Duurzame inzetbaarheid op het werk: interventies, best practices en integrale benaderingen [Employable for life? Sustainable employability at work: interventions, best practices and integrated approaches] Alphen a/d Rijn: Vakmedianet; 2013.

Een kwestie van gezond verstand: breed preventiebeleid binnen arbeidsorganisaties [Common sense: comprehensive prevention policies in labour organisations]. Den Haag: Sociaal-Economische Raad; 2009.

Van Vuuren T, Caniëls MCJ, Semeijn JH. Duurzame inzetbaarheid en een leven lang leren [Sustainable employability and lifelong learning]. Gedrag en Organisatie, 2011;24(4):356–73.

Ilmarinen J, Tuomi K, Seitsamo J. New dimensions of work ability. Int Congr Ser. 2005;1280:3–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ics.2005.02.060

World Health Organization. ‘Preamble to the constitution of the World Health Organization, entered into force on 7 April 1948, Official Records of the World Health Organization, no. 2, p. 100’, adopted by the International Health Conference 1946, New York, p. 19–22

Bakker AB, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP, Taris TW. Work engagement: an emerging concept in occupational health psychology. Work Stress. 2008;22(3):187–200.

Ryan RM, Frederick C. On energy, personality, and health: subjective vitality as a dynamic reflection of well-being. J Pers. 1997;65(3):529–65.

De Vos A, Van der Heijden BIJM. Handbook of research on sustainable careers. Cheltenham, UK Northhampton, MA, USA: Edward Elgar Publishing; 2017, p. 461.

Cloostermans L, Bekkers MB, Uiters E, Proper KI. The effectiveness of interventions for ageing workers on (early) retirement, work ability and productivity: a systematic review. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2015;88(5):521–32.

Oakman J, Neupane S, Proper KI, Kinsman N, Nygård CH. Workplace interventions to improve work ability: a systematic review and meta-analysis of their effectiveness. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2018;44(2):134–46.

Hazelzet E, Picco E, Houkes I, Bosma H, de Rijk A. Effectiveness of interventions to promote sustainable employability: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(11):1985.

Peeters MCW, De Jonge J, Taris TW. An introduction to contemporary work psychology. Chichester: Wiley; 2013. p. 510.

Nielsen K, Taris TW, Cox T. The future of organizational interventions: addressing the challenges of today’s organizations. Work Stress. 2010;24(3):219–33.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JPA, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–34.

De Lange A, Van der Heijden BIJM. Een leven lang inzetbaar?: Duurzame inzetbaarheid op het werk: Interventies, best practices en integrale benaderingen [Employable for life? Sustainable employability at work: interventions, best practices and integrated approaches.] Alphen aan den Rijn: Vakmedianet: 2013.

Van Dam K, Van Vuuren T, Kemps S. Sustainable employment: the importance of intrinsically valuable work and an age-supportive climate. Int J Hum Resour Manag. 2017;28(17):2449–72.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, The PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097.

Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A. Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210.

Ciliska D, Miccuci S, Dobbins M, Thomas BH. Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies [Internet]. Effective Public Healthcare Panacea Project. 1998 [cited 2021 Mar 5]. https://www.ephpp.ca/quality-assessment-tool-for-quantitative-studies/

Deeks JJ, Dinnes J, D’amico R, Sowden AJ, Sakarovitch C, Song F, et al. Evaluating non-randomised intervention studies. Health Technol Assess. 2003 Sep;7(27).

Thomas BH, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2004;1(3):176–84.

Hoogendoorn WE, van Poppel MNM, Bongers PM, Koes BW, Bouter LM. Systematic review of psychosocial factors at work and private life as risk factors for back pain. Spine. 2000;25(16):2114–25.

Van Drongelen A, Boot CR, Merkus S, Smid T, van der Beek AJ. The effects of shift work on body weight change; a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Scand J Work Environ Health. 2011;37(4):263–75.

Barbosa A, Nolan M, Sousa L, Figueiredo D. supporting direct care workers in dementia care: effects of a psychoeducational intervention. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2015;30(2):130–8.

Barbosa A, Nolan M, Sousa L, Marques A, Figueiredo D. Effects of a psychoeducational intervention for direct care workers caring for people with dementia: results from a 6-month follow-up study. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Demen. 2016;31(2):144–55.

Dulon M, Pohrt U, Skudlik C, Nienhaus A. Prevention of occupational skin disease: a workplace intervention study in geriatric nurses. Br J Dermatol. 2009;161(2):337–44.

Engst C, Chhokar R, Miller A, Tate R, Yassi A. Effectiveness of overhead lifting devices in reducing the risk of injury to care staff in extended care facilities. Ergonomics. 2005;48(2):187–99.

Moyle W, Cooke M, O’Dwyer ST, Murfield J, Johnston A, Sung B. The effect of foot massage on long-term care staff working with older people with dementia: a pilot, parallel group, randomized controlled trial. BMC Nurs. 2013;12(1):5.

Skargren E, Öberg B. Effects of an exercise program on musculoskeletal symptoms and physical capacity among nursing staff. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1996;6(2):122–30.

Rasmussen CDN, Holtermann A, Bay H, Søgaard K, Birk JM. A multifaceted workplace intervention for low back pain in nurses’ aides: a pragmatic stepped wedge cluster randomised controlled trial. Pain. 2015;156(9):1786–94.

Kuske B, Luck T, Hanns S, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC, Behrens J, et al. Training in dementia care: a cluster-randomized controlled trial of a training program for nursing home staff in Germany. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(02):295.

O’Brien WH, Singh R, Horan K, Moeller MT, Wasson R, Jex SM. Group-based acceptance and commitment therapy for nurses and nurse aides working in long-term care residential settings. J Altern Complement Med. 2019;25(7):753–61.

Buruck G, Dörfel D, Kugler J, Brom SS. Enhancing well-being at work: The role of emotion regulation skills as personal resources. J Occup Health Psychol. 2016;21(4):480–93.

Franzmann J, Haberstroh J, Pantel J. Train the trainer in dementia care: a program to foster communication skills in nursing home staff caring for dementia patients. Z Für Gerontol Geriatr. 2016;49(3):209–15.

Brazil K, Jewell A, Lyle C, Zuraw L, Stanton S. Assessing the impact of staff development on nursing practice. J Nurses Staff Dev JNSD. 1998;14(4):198–204.

Broughton M, Smith ER, Baker R, Angwin AJ, Pachana NA, Copland DA, et al. Evaluation of a caregiver education program to support memory and communication in dementia: a controlled pretest–posttest study with nursing home staff. Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(11):1436–44.

Davison TE, McCabe MP, Visser S, Hudgson C, Buchanan G, George K. Controlled trial of dementia training with a peer support group for aged care staff. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;22(9):868–73.

Fukuda K, Terada S, Hashimoto M, Ukai K, Kumagai R, Suzuki M, et al. Effectiveness of educational program using printed educational material on care burden distress among staff of residential aged care facilities without medical specialists and/or registered nurses: cluster quasi-randomization study: effect of PEM on burden among care staff. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2018;18(3):487–94.

Schrijnemaekers VJJ, van Rossum E, Candel MJJM, Frederiks CMA, Derix MMA, Sielhorst H, et al. Effects of emotion-oriented care on work-related outcomes of professional caregivers in homes for elderly persons. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58(1):S50–7.

Visser SM, Mccabe MP, Hudgson C, Buchanan G, Davison TE, George K. Managing behavioural symptoms of dementia: Effectiveness of staff education and peer support. Aging Ment Health. 2008;12(1):47–55.

Zwijsen SA, Gerritsen DL, Eefsting JA, Smalbrugge M, Hertogh CMPM, Pot AM. Coming to grips with challenging behaviour: a cluster randomised controlled trial on the effects of a new care programme for challenging behaviour on burnout, job satisfaction and job demands of care staff on dementia special care units. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(1):68–74.

Kloos N, Drossaert CHC, Bohlmeijer ET, Westerhof GJ. Online positive psychology intervention for nursing home staff: a cluster-randomized controlled feasibility trial of effectiveness and acceptability. Int J Nurs Stud. 2019;98:48–56.

Kossek EE, Thompson RJ, Lawson KM, Bodner T, Perrigino MB, Hammer LB, et al. Caring for the elderly at work and home: can a randomized organizational intervention improve psychological health? J Occup Health Psychol. 2019;24(1):36–54.

Mackenzie CS, Peragine G. Measuring and enhancing self-efficacy among professional caregivers of individuals with dementia. Am J Alzheimers Dis Dementiasr. 2003;18(5):291–9.

Pillemer K, Suitor JJ, Henderson CR, Meador R, Schultz L, Robison J, et al. A cooperative communication intervention for nursing home staff and family members of residents. The Gerontol. 2003;43(Suppl 2):96–106.

Yu CY, Chen KM. Experiencing simulated aging improves knowledge of and attitudes toward aging. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2012;60(5):957–61.

Bourgeois MS, Dijkstra K, Burgio LD, Allen RS. Communication skills training for nursing aides of residents with dementia: the impact of measuring performance. Clin Gerontol. 2004;27(1–2):119–38.

Ersek M, Grant MM, Kraybill BM. Enhancing end-of-life care in nursing homes: palliative care educational resource team (PERT) program. J Palliat Med. 2005;8(3):556–66.

Janssens B, Vanobbergen J, Lambert M, Schols JMGA, De Visschere L. Effect of an oral healthcare programme on care staff knowledge and attitude regarding oral health: a non-randomised intervention trial. Clin Oral Investig. 2018;22(1):281–92.

Janssens B, De Visschere L, van der Putten GJ, de Lugt-Lustig K, Schols JMGA, Vanobbergen J. Effect of an oral healthcare protocol in nursing homes on care staffs’ knowledge and attitude towards oral health care: a cluster-randomised controlled trial. Gerodontology. 2016;33(2):275–86.

Kong EH, Song E, Evans LK. Effects of a multicomponent restraint reduction program for Korean nursing home staff. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2017;49(3):325–35.

Mellor D, Mccabe M, Davison T, Karantzas G, George K. An evaluation of the beyondblue depression training program for aged care workers. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(S2):843–843.

Pellfolk TJE, Gustafson Y, Bucht G, Karlsson S. Effects of a restraint minimization program on staff knowledge, attitudes, and practice: a cluster randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(1):62–9.

Chang CC. Effects of a Feeding Skills Training Program on Knowledge, Attitude, Perceived Behavior Control, Intention, and Behavior of Formal Caregivers Toward Feeding Dementia Patient in Taiwan Nursing Homes [Internet]. [Ann Arbor]: Case Western Reserve University; 2005 [cited 2021 Mar 7]. https://etd.ohiolink.edu/apexprod/rws_olink/r/1501/10?clear=10&p10_accession_num=case1093631995

Franche RL, Cullen K, Clarke J, Irvin E, Sinclair S, Frank J, et al. Workplace-based return-to-work interventions: a systematic review of the quantitative literature. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15(4):607–31.

Brunero S, Lamont S, Coates M. A review of empathy education in nursing. Nurs Inq. 2010;17(1):65–74.

Coffey A, Saab MM, Landers M, Cornally N, Hegarty J, Drennan J, et al. The impact of compassionate care education on nurses: a mixed-method systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2019;75(11):2340–51.

Van der Klink JJL, Burdorf A, Schaufeli WB, Van der Wilt GJ, Zijlstra FRH, Brouwer S, et al. Duurzaam Inzetbaar: Werk als Waarde [Sustainable Employability: Work as Value] [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2019 Sep 17]. https://www.voion.nl/downloads/d83f3d24-c126-4947-8cd1-6798565acbff

Kristensen TS. Intervention studies in occupational epidemiology. Occup Environ Med. 2005;62(3):205–10.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. Chichester: Wiley; 2009. p. 421.

Wasserstein RL, Lazar NA. The ASA statement on p -values: context, process, and purpose. Am Stat. 2016;70(2):129–33.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the librarians of the Radboud University who helped developing our search strategy.

Funding

This study was funded by the Foundation Joannes de Deo, 24001506 (ID 243207). This foundation aims to support research activities contributing to knowledge and quality of care for older adults. The funder had no role in the conduct of this review.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Together with an information specialist CH designed the search strategy, in consultation with the other authors. The literature search was performed by CH. CH and AdW screened titles and abstracts and assessed the articles that were selected for full text appraisal. MvH and CB were consulted in case of disagreement. CH extracted the data in collaboration with AdW, and in some instances other authors. The methodological quality of the studies was assessed by CH and AdW independently. The level of evidence rating scheme was discussed with all authors, performed by CH, and checked by the others. CH had a leading role in writing the manuscript, with all authors critically revising the manuscript, providing intellectual input and approval of the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Heijkants, C.H., de Wind, A., van Hooff, M.L.M. et al. Effectiveness of Team and Organisational Level Workplace Interventions Aimed at Improving Sustainable Employability of Aged Care Staff: A Systematic Review. J Occup Rehabil 33, 37–60 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10064-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-022-10064-5