Abstract

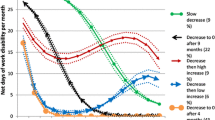

Purpose The return to work (RTW) of people with mood and anxiety disorders is a heterogeneous process. We aimed to identify prototypical trajectories of RTW over a two-year period in people on sick leave with mood and anxiety disorders, and investigate if socio-demographic or clinical factors predicted trajectory membership. Methods We used data from the randomized IPS-MA trial (n = 283), evaluating a supported employment intervention for participants with recently diagnosed mood or anxiety disorders. Information on “weeks in employment in the past 6 months” was measured after 1/2, 1, 1 ½ and 2 years, using data from a nationwide Danish register (DREAM). Latent growth mixture modelling analysis was carried out to identify trajectories of RTW and logistic regression analyses were used to estimate predictors for trajectory membership. Results Four trajectory classes of RTW were identified; non-RTW [70% (196/283)] (practically no return to work); delayed-RTW [19% (56/283)] (6 months delay before full RTW); rapid-unstable-RTW [7% (19/283)] (members rapidly returned to work, but only worked half the time); and the smallest class, rapid-RTW [4% (12/283)] (members rapidly reached full employment, but later experienced a decrease in weeks of employment). Self-reported disability score according to the SDS, not living with a partner, and readiness to change on the CQ scale were found to be significantly associated with RTW. Conclusion The trajectories identified support that many do not benefit from vocational rehabilitation, or experience difficulties sustaining employment; enhanced support of this patient group is still warranted.

Trial registration: http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT01721824)

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2013;380(9859):2163–2196.

Flachs EM, Eriksen L, Koch MB, Ryd JT, Dibba E, Skov-Ettrup LJK. Sygdomsbyrden i Danmark: sygdomme. København: Sundhedsstyrelsen; 2015.

Hellström L, Bech P, Hjorthøj C, Nordentoft M, Lindschou J, Eplov LF. Effect on return to work or education of individual placement and support modified for people with mood and anxiety disorders: results of a randomised clinical trial. Occup Environ Med. 2017;74(10):717–725.

Reme SE, Grasdal AL, Løvvik C, Lie SA, Øverland S. Work-focused cognitive-behavioural therapy and individual job support to increase work participation in common mental disorders: a randomised controlled multicentre trial. Occup Environ Med. 2015;72(10):745–752.

Himle JA, Bybee D, Steinberger E, Laviolette WT, Weaver A, Vlnka S, Golenberg Z, Levine DS, Heimberg RG, O’Donnell LA. Work-related CBT versus vocational services as usual for unemployed persons with social anxiety disorder: a randomized controlled pilot trial. Behav Res Ther. 2014;63:169–176.

Vlasveld MC, van der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Ader HJ, Anema JR, Hoedeman R, van Mechelen W, et al. Collaborative care for sick-listed workers with major depressive disorder: a randomised controlled trial from the Netherlands Depression Initiative aimed at return to work and depressive symptoms. Occup Environ Med. 2012;70(4):223–230.

Hees HL, de Vries G, Koeter MWJ, Schene AH. Adjuvant occupational therapy improves long-term depression recovery and return-to-work in good health in sick-listed employees with major depression: results of a randomised controlled trial. Occup Environ Med. 2013;70(4):252–260.

Nandi A, Beard JR, Galea S. Epidemiologic heterogeneity of common mood and anxiety disorders over the lifecourse in the general population: a systematic review. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:31–42.

Pedersen P, Lund T, Lindholdt L, Nohr EA, Jensen C, Søgaard HJ, et al. Labour market trajectories following sickness absence due to self-reported all cause morbidity: a longitudinal study. BMC Public Health. 2016;16(1):337–347.

van Vilsteren M, van Oostrom SH, de Vet HCW, Franche RL, Boot CRL, Anema JR. Workplace interventions to prevent work disability in workers on sick leave. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;10(10):CD006955.

Oyeflaten I, Lie SA, Ihlebæk CM, Eriksen HR. Multiple transitions in sick leave, disability benefits, and return to work. A 4-year follow-up of patients participating in a work-related rehabilitation program. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):748–756.

Lammerts L, Schaafsma FG, Eikelenboom M, Vermeulen SJ, van Mechelen W, Anema JR, et al. Longitudinal associations between biopsychosocial factors and sustainable return to work of sick-listed workers with a depressive or anxiety disorder. J Occup Rehabil. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-015-9588-z

Vemer P, Bouwmans CA, Zijlstra-Vlasveld MC, van Der Feltz-Cornelis CM, Hakkaart-van Roijen L, Roijen LH. Let’s get back to work: survival analysis on the return-to-work after depression. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:1637–1645.

Arvilommi P, Suominen K, Mantere O, Valtonen H, Leppamaki S, Isometsa E. Predictors of long-term work disability among patients with type I and II bipolar disorder: a prospective 18-month follow-up study. Bipolar Disord. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12349

Dewa CS, Hoch JS, Lin E, Paterson M, Goering P. Pattern of antidepressant use and duration of depression-related absence from work. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;183(6):507–513.

Koopmans PC, Roelen CAM, Groothoff JW. Sickness absence due to depressive symptoms. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2008;81(6):711–719.

Waghorn G, Chant D, Harris MG. The stability of correlates of labour force activity. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2009;119(5):393–405.

Hees HL, Koeter MWJ, Schene AH. Predictors of long-term return to work and symptom remission in sick-listed patients with major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(8):1048–1055.

Riihimäki K, Vuorilehto M, Isometsä E. A 5-year prospective study of predictors for functional and work disability among primary care patients with depressive disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2015;30(1):51–57.

Waghorn G, Chant D. Work performance among Australians with depression and anxiety disorders: a population level second order analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194(12):898–904.

Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Chelminski I, Young D, Dalrymple K, Ruggero CJ. Sustained unemployment in psychiatric outpatients with bipolar disorder: frequency and association with demographic variables and comorbid disorders. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(7):720–726.

Lamberg T, Virtanen P, Vahtera J, Luukkaala T, Koskenvuo M. Unemployment, depressiveness and disability retirement: a follow-up study of the Finnish HeSSup population sample. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2010;45(2):259–264.

Tolman RM, Himle J, Bybee D, Abelson JL, Hoffman J, Van Etten-Lee M. Impact of social anxiety disorder on employment among women receiving welfare benefits. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(1):61–66.

Banerjee S, Chatterji P, Lahiri K. Identifying the mechanisms for workplace burden of psychiatric illness. Med Care. 2014;52(2):112–120.

Druss BG, Schlesinger M, Allen HM. Depressive symptoms, satisfaction with health care, and 2-year work outcomes in an employed population. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158(5):731–734.

Nielsen MBD, Bültmann U, Madsen IEH, Martin M, Christensen U, Diderichsen F, et al. Health, work, and personal-related predictors of time to return to work among employees with mental health problems. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(15):1311–1316.

Bultmann U, Rugulies R, Lund T, Christensen KB, Labriola M, Burr H. Depressive symptoms and the risk of long-term sickness absence: a prospective study among 4747 employees in Denmark. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006;41(11):875–880.

Lee RSC, Hermens DF, Naismith SL, Lagopoulos J, Jones A, Scott J, et al. Neuropsychological and functional outcomes in recent-onset major depression, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia-spectrum disorders: a longitudinal cohort study. Transl Psychiatry. 2015;5(4):e555–e565.

Hellström L, Bech P, Nordentoft M, Lindschou J, Eplov LF. The effect of IPS-modified, an early intervention for people with mood and anxiety disorders: study protocol for a randomised clinical superiority trial. Trials. 2013;14(1):442–452.

The Danish Agency for Labour Market and Recruitment. The DREAM database, Statistics Denmark [DREAM databasen, Danmarks Statistik]. Copenhagen: The National Labour Market Authority; 2015.

The Civil Registration System (CPR-register) [Internet]. Available from https://www.cpr.dk/.

O’Sullivan RL, Fava M, Agustin C, Baer L, Rosenbaum JF. Sensitivity of the six-item Hamilton depression rating scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1997;95(5):379–384.

Bech P. Clinical psychometrics. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2012.

Maier W, Buller R, Philipp M, Heuser I. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale: reliability, validity and sensitivity to change in anxiety and depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 1988;14(1):61–68.

Pedersen G, Karterud S. The symptom and function dimensions of the global assessment of functioning (GAF) scale. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(3):292–298.

Sheehan DV, Harnett-Sheehan K, Raj BA. The measurement of disability. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1996;11(Suppl 3):89–95.

Rogers ES, Chamberlin J, Ellison ML, Crean T. A consumer-constructed scale to measure empowerment among users of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48(8):1042–1047.

Miller WR, Johnson WR. A natural language screening measure for motivation to change. Addict Behav. 2008;33(9):1177–1182.

Jung T, Wickrama K. An introduction to latent class growth analysis and growth mixture modeling. Soc Personal Psychol. 2008;2(1):302–317.

Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7th edn. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2012.

Clark SL, Muthén B. Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. https://www.statmodel.com/download/relatinglca.pdf. Accessed 13 July 2015.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Faber B, Verbeek JH, Neumeyer-Gromen A, Hees HL, Verhoeven AC, et al. Interventions to improve return to work in depressed people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;12(12):CD006237.

Bejerholm U, Larsson ME, Johanson S. Supported employment adapted for people with affective disorders: a randomized controlled trial. J Affect Disord. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2016.08.028

Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S. Work outcomes of sickness absence related to mental disorders: a systematic literature review. BMJ Open. 2014;4(7):e005533–e005548.

Nielsen MBD, Bültmann U, Amby M, Christensen U, Diderichsen F, Rugulies R, et al. Return to work among employees with common mental disorders: study design and baseline findings from a mixed-method follow-up study. Scand J Public Health. 2010;38(8):864–872.

Nieuwenhuijsen K, Noordik E, Van Dijk FJH, Van Der Klink JJ. Return to work perceptions and actual return to work in workers with common mental disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2013;23(2):290–299.

Holma IA, Holma KM, Melartin TK, Rytsälä HJ, Isometsä ET. A 5-year prospective study of predictors for disability pension among patients with major depressive disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125(4):325–334.

Fleten N, Johnsen R, Førde OH. Length of sick leave: why not ask the sick-listed? Sick-listed individuals predict their length of sick leave more accurately than professionals. BMC Public Health. 2004;4(1):46–57.

Joyce S, Modini M, Christensen H, Mykletun A, Bryant R, Mitchell PB, et al. Workplace interventions for common mental disorders: a systematic meta-review. Psychol Med. 2016;46(July):683–697.

Funding

The randomized trial was funded by the Obel Family Foundation, the Tryg Foundation, and the Danish Agency for Labour Market and Recruitment. No current or future sponsors of the trial have had any role in the trial design, collection of data, analysis of data, data interpretation, or in publication of data from the trial.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LH did the scientific literature search, study design of analysis, participated in the data analysis, data interpretation, drafting of figures and writing of the manuscript. TM participated in the study design of analysis, conducted the data analysis, data interpretation, drafting of figures and co-writing of the manuscript. LFE took part in planning and design of the study, interpretation of analysis and co-writing of the manuscript. PB and MN took part in interpretation of the analysis, and co-writing of the manuscript. All authors have read and critically revised the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

The study was approved by The Regional Ethics Committees of the Capital Region (journal no: H-2-2011-FSP20), reported to the Danish Data Protection Agency (Journal no: 2007-58-0015, local Journal no: RHP-2011-20), and registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov (Identifier: NCT01721824).

Informed Consent

All participants provided oral and written informed consent prior to inclusion in the study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hellström, L., Madsen, T., Nordentoft, M. et al. Trajectories of Return to Work Among People on Sick Leave with Mood or Anxiety Disorders: Secondary Analysis from a Randomized Controlled Trial. J Occup Rehabil 28, 666–677 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9750-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-017-9750-x