Abstract

Introduction There are substantial differences in the number of disability benefits for occupational low back pain (LBP) among countries. There are also large cross country differences in disability policies. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) there are two principal policy approaches: countries which have an emphasis on a compensation policy approach or countries with an emphasis on an reintegration policy approach. The International Social Security Association initiated this study to explain differences in return-to-work (RTW) among claimants with long term sick leave due to LBP between countries with a special focus on the effect of different disability policies. Methods A multinational cohort of 2,825 compensation claimants off work for 3–4 months due to LBP was recruited in Denmark, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the United States. Relevant predictors and interventions were measured at 3 months, one and 2 years after the start of sick leave. The main outcome measure was duration until sustainable RTW (i.e. working after 2 years). Multivariate analyses were conducted to explain differences in sustainable RTW between countries and to explore the effect of different disability policies. Results Medical and work interventions varied considerably between countries. Sustainable RTW ranged from 22% in the German cohort up to 62% in the Dutch cohort after 2 years of follow-up. Work interventions and job characteristics contributed most to these differences. Patient health, medical interventions and patient characteristics were less important. In addition, cross-country differences in eligibility criteria for entitlement to long-term and/or partial disability benefits contributed to the observed differences in sustainable RTW rates: less strict criteria are more effective. The model including various compensation policy variables explained 48% of the variance. Conclusions Large cross-country differences in sustainable RTW after chronic LBP are mainly explained by cross-country differences in applied work interventions. Differences in eligibility criteria for long term disability benefits contributed also to the differences in RTW. This study supports OECD policy recommendations: Individual packages of work interventions and flexible (partial) disability benefits adapted to the individual needs and capacities are important for preventing work disability due to LBP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Over the last decades work disability rates and corresponding costs have risen in most industrialised countries [1]. In the western world, work disability has become a major public health and economic problem. Long term sickness absence and work disability is associated with (work related) health risks, future serious illness and even an increased mortality risk [2]. From a societal perspective, the total yearly work disability costs are large. In the United Kingdom, the yearly costs are estimated at 24 billion pounds, and up to seventy-five percent of the total absence costs are associated with long-term absence [3, 4]. In the United States, workers’ insurance costs employers 2 to 4% of their gross earnings [5].

Low back pain (LBP) is the most common reason for long-term absence and work disability in the US and other industrialized countries [6]. There are substantial differences in the prevalence of disability benefits and claim rates among countries [1]. For example, the back claim rate in the United States is 60-fold higher than that in Japan [7]. In the back pain literature, it is often argued that different disability policies could explain these differences in claim rates and long-term disability benefits [1]. There are large cross country differences in disability policies. According to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) there are two principal disability policy approaches: there are countries which have an emphasis on a compensation policy approach, with broad access to disability benefits, combined with fewer reintegration efforts, and there are countries with an emphasis on an reintegration policy approach, stimulating primarily reintegration measures with more restricted access to disability benefits [8]. Due to a lack of evidence there is a debate among politicians and researchers which disability policies stimulate return-to-work (RTW) and which policies delay functional recovery and cause unnecessarily sickness absence and even long-term work disability [9–12].

Several years ago the International Social Security Agency (ISSA) initiated a multinational cohort study to evaluate the national differences in RTW and the effect of several predictors and interventions in six different countries with a special focus on (dis)incentives in their compensation systems. LBP was used as an example due to its high prevalence and the variation in prevalence of disability benefits between countries. The biopsychosocial model of pain and disability provided a theoretical framework for this study [13]. In addition, compensation policy variables that may be obstacles for recovery and RTW were defined. These variables have been labelled “black flags” and are beyond individual control [14]. The aim of this study is to explain differences in RTW among claimants with long term sick leave due to LBP between countries with a special focus on the effect of these insurance variables.

Methods

Study Design

We collected data from six cohort studies of occupational LBP and analysed them together. Two-year follow-up data from claimants sicklisted due to occupational LBP in Denmark, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, Sweden, and the USA (states of New Jersey and California) were analyzed. Because these studies had a core design comprising several identical basic features [15–19], it was possible to collapse the datasets into a homogenous internationally standardised dataset for multinational analysis [19].

Recruitment and Data Collection

A series of 2,825 claimants was recruited by national research teams during the period from May 1995 to September 1996, using databases of sickness benefit claimants in the participating countries. Detailed information about the data sources has been provided elsewhere [16]. All claimants were asked to participate and to sign a letter of authorisation, permitting their data to be used for the cohort study. Data were collected using questionnaires and interviews at 3–4 months (baseline), one (T2) and 2 years (T3) after the first day of sick leave. The response rates at T2 and T3 were 85 and 77%, respectively. Non-response analysis showed that there were no major differences between the response group and the non-response group with regard to demographic characteristics [16]. Three-hundred and twenty-eight cases had missing values in the database for the date of RTW. All of these 328 cases were at work at T3. We constructed the date of RTW for 305 of these cases on the basis of the other available data: work status at T2 and other available dates (day, month and year) regarding RTW in the database.

Study Population

We included claimants with LBP, i.e. pain between the lower edge of 12th rib and the gluteal folds. To be included, claimants had to be between 18 and 59 years of age. We excluded claimants with spinal fractures, with spinal surgery within the previous 12 months and those with an infectious or with malignant cause for their back pain. Claimants had to have completely stopped working due to LBP during 3 months before entry to the cohorts (i.e. they were in their 4th month of work disability). The baseline characteristics of all 2,825 participants in the 6 national cohorts have been described in detail elsewhere [16, 17].

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was work disability duration until sustainable RTW [18]. Two outcome measures were collected in the international database: 1. Date of RTW; and 2. Working status at T2 and T3. RTW was defined as ‘long-lasting’ or sustainable if RTW started during follow-up and a claimant was (still) working at T3. Work disability duration until sustainable RTW was defined as the number of days from first day of sick leave until first date of work resumption resulting in sustainable RTW [18]. For claimants who did not work at T3, work disability duration until sustainable RTW was censored. This primary outcome is hence forward called ‘work disability duration until sustainable RTW’ or shortly ‘sustainable RTW’.

Biopsychosocial and Compensation Policy Variables

Biopsychosocial variables were selected after a literature review [16] and based on their known or suspected influence on RTW. Patient characteristics, patient health, job characteristics, medical interventions, and work interventions were derived from the international database [19] and used in our multivariable model (see Table 1). For the multinational analyses, we selected only those variables that were measured in all participating countries. Detailed information about the content and categorisation of these variables is available in another publication [18] and the technical guide of the International Database [19]. Main characteristics of compensation systems in the involved countries were defined before the onset of the study into compensation policy variables by the members of all national research teams [16]. For this analysis, these variables were dichotomised as present or absent in a specific compensation system (see Table 2). Disability policies are according to the definition of the OECD [8] defined as the total of compensation policy policies and work reintegration measures in a country or state.

Statistical Data Analysis

Baseline descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables. The association between variables potentially explaining the differences between countries and work disability duration was assessed using a Cox proportional hazard model, in order to identify the best fitting multivariate model. Five blocks with variables that could potentially explain the differences between countries were identified: patient characteristics, health-related variables, job characteristics, medical interventions and work interventions. First, for each block all relevant variables within that specific block were entered in one step into the Cox regression model to calculate the relative contribution of each block to the cross country differences in work disability duration. Clustering of observations within countries was taken into account by conducting a Cox regression with countries as strata. Second, variables of all blocks were tested using stepwise statistical procedures (backward procedure) to construct the best fitting basic model to explain the differences in work disability duration between countries. The alpha criterion for stepwise selection of variables was set at 0.10. Third, the compensation policy variables were entered one by one into the basic model of the resulting variables of the five blocks. The order of entrance of the compensation policy variables was based on the strength of the Wald statistic. In this third step Cox regression analysis was only possible if country was not handled as strata. The proportion of explained variation in work disability duration was calculated for all blocks separately and for the final model (including the compensation policy variables) with the pseudo R 2 [20]. Interactions between age and comorbidity, and interactions between age and pain were tested based on concerns that age could modify the effects of these variables. In addition, based on concerns that compensation policy variables could modify the effects of work interventions, interactions between compensation policy variables and work interventions were tested by taking the compensation policy variables as strata in the Cox regression one by one. The assumption of a constant proportional hazard was tested for each compensation policy variable in the final model. Finally, a missing data analysis was conducted by comparing the multivariable samples on demographic, work and back pain characteristics (age, gender, pain intensity, sciatica, Hannover ADL, and working hours) to the samples of the participants with missing data.

Results

Cross-National Differences in Medical Interventions and Work Interventions

There were substantial differences in the applied medical interventions and work interventions in the six countries during follow-up. The USA had the highest frequency in surgery (35.1%), Israel and Denmark in pain relieving medication (86.9 and 78.9%, respectively), Germany in passive treatment and manipulation (41.7%), the USA and the Netherlands in exercise therapy (63.0%), and Germany and Denmark in back schools (28%). The differences in frequencies of medical interventions between counties were all significant (P ≤ 0.001). The frequency of ‘therapeutic work resumption’ (60.0%) and ‘working hours adaptation’ (49.2%) was high in the Netherlands. High frequencies for work interventions were also found in the Israeli (job redesign 43.7%) and in the Swedish cohort (job training 18.0%). In Germany, the frequencies of work interventions were the lowest for all types of work interventions. The differences in frequencies of work interventions between countries were all significant (P ≤ 0.001; Table 3).

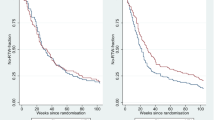

Differences Between Countries in Sustainable RTW

A total of 1,156 out of 2,825 claimants (41.3%) had a sustainable RTW at T3 (i.e. 2 years after the first day of sick leave). Figure 1 demonstrates the Kaplan–Meier survival curves for work disability duration until sustainable RTW stratified for countries. As shown in Fig. 1, sustainable RTW at T3 varied considerably between countries (log rank test P < 0.001): ranging from 22% of the claimants in the German cohort to 62% of the claimants in the Dutch cohort. Sustainable RTW at T3 was found in 31, 39, 49 and 49% of the claimants in the Danish, Swedish, American and Israeli cohort, respectively. In addition, RTW-patterns in the first and second year varied between countries.

Explaining Biopsychosocial and Compensation Policy Variables for Differences in RTW Between Countries

First, a basic Cox regression model (with the biopsychosocial variables, without the compensation policy variables) was constructed to explain the observed differences in duration until sustainable RTW and to determine the relative contribution of the five blocks of biopsychosocial variables to the explained variance. The first block (I), patient characteristics, had a relatively small contribution to explained variance (6%; pseudo R 2 = 0.06). Health-related variables at T1 (block II) explained 21% of the differences in duration until sustainable RTW. For block (III), job characteristics, the explained variance was 22%. Medical interventions (block IV) contributed to 18% of the explained variance. The last block (V), work interventions, accounted for 26% of the variance in (differences in) RTW.

Subsequently, the compensation policy variables were entered into the basic Cox regression model. This final model is presented in Table 4. For three health-related variables, there was an association with earlier sustainable RTW: no co-morbidity interference, a lower pain intensity and less functional limitations (i.e. higher score on the Hannover ADL scale). The following job characteristics were associated with earlier sustainable RTW: longer tenure, higher work ability score, less physical job demands (i.e. higher score) and less job strain. There was an association with earlier sustainable RTW for the following medical interventions: surgery (at T0–T1), no surgery (at T2–T3), pain medication (at T0–T2), pain medication (at T2–T3), exercise therapy (at T0–T2). Four work interventions were related to earlier sustainable RTW: adaptation of the workplace, job redesign, working hours adaptation, and therapeutic work resumption (i.e. work resumption with ongoing benefits). For the following compensation policy variables for entitlement to benefits, an effect on earlier sustainable RTW was found: no or late timing of entitlement (>3 months after onset claim) to a long-term disability benefit (P < 0.001) and no high minimum (50% or less) degree of work incapacity needed for a long-term partial disability benefit (P < 0.001). Medical certificates needed for a benefit was not significant in the final model (P = 0.07). One compensation policy variable, waiting days before getting a sickness benefit, was left out of the final model, because it was not significant and caused multi-co linearity. There were no significant interaction effects found between compensation policy variables and work interventions in the model. Proportional hazard assumption was met for each compensation policy variable in the final model. The total explained variance of the final model, including the compensation policy variables, was 48%.

Missing Data Analysis

A small proportion (13.5%) of all participants (n = 381) had missing data in the multivariable analyses. Those in the model (n = 2,444) had similar demographic, job and back pain characteristics compared to those with missing data (n = 381), although two characteristics—for pain intensity and working hours—were statistically significant (P < 0.05).

Discussion

From a Biopsychosocial Model to a Biopsychosocial-Political Model

With the biopsychosocial model [13] as a framework we studied the contribution of medical, psychological, social (occupational), and compensation policy variables to explain the differences between six countries in sustainable RTW among LBP claimants. This study showed that occupational back pain disability is more of a socio political than a medical problem. Cross-country differences in applied work interventions and eligibility criteria for long-term disability benefits contributed to the observed differences in RTW-rates. Work interventions and less strict compensation policies to be eligible for long-term (partial) benefits, contributed to sustainable RTW.

Comparison with Other Studies

To date, in a few studies the effect of compensation policy variables is described. Cassidy et al. [21] showed that a system change from a ‘tort’ insurance system to a ‘no fault’ system in Saskatchewan, Canada, was associated with a decrease in the incidence and duration of claims and with faster recovery of those with whiplash injuries. Similar results were found for those with LBP and mild brain injuries [22, 23].

Another example is a replication of a study in a different compensation system, e.g. studies evaluating the Sherbrooke model in Canada and the Netherlands [24, 25]. Despite the different socio-political context, the effectiveness of work interventions on RTW after LBP in the Canadian study was to a large extent replicated in the Dutch study.

In former studies on this multinational cohort study it was shown that work interventions were effective on RTW in LBP claimants, whereas medical interventions were in general not effective in the participating countries [17, 18]. This study adds that it shows that the large cross country differences in RTW were mainly explained by differences in applied work interventions in the cohorts. In addition, it showed that compensation policy variables independently explained part of these differences in RTW.

Strengths

It is stated that new methodology in health policy research, e.g. multinational cohort studies, is strongly needed to allow evidence based policy development [26]. To date, the influence of a compensation policy change on outcomes has been studied in only one before-after design in one jurisdiction of Canada [21–23]. In contrast to the multinational cohort design, before-after designs are more susceptible to bias: compensation policy changes frequently coincide with and cannot always be disentangled from other socioeconomic or political changes. In addition, due to the multinational design the external validity of the findings of the present study is larger than in studies conducted in one state or country. Because compensation policy variables cannot be studied in randomised controlled studies, a multinational cohort design seems the best option in health policy research. Therefore, this study and its methodology are a unique contribution to the evidence base in the field of back pain and health policy research.

Weaknesses

The observational design is a strength as well as a limitation of this study. The (demographic) differences at baseline between the national cohorts might have led to bias. We attempted to limit this bias by adding these demographic characteristics to the biopsychosocial and compensation policy variables in the explaining model. Baseline differences in demographic characteristics appeared to have no important contribution to the differences in sustainable RTW. Although we did not find any relevant interaction effects between compensation policy variables and the work interventions, the effect of compensation policy variables could be determined (partially) by other unknown variables that coincide or highly correlate with the studied compensation policy variables. Finally, the compensation policy variables we studied were previously defined by the members of all national research teams [16] and dichotomised for this analysis on a theoretical basis. It was assumed by the panel that these compensation policy variables have an influence on differences in RTW between countries in RTW. This assumption was, however, not based on any previous research, due to a lack of health policy research in this field. Hence, it might be that relevant compensation policy variables were not included in the present study.

Policy Implications

In many countries, e.g. in the USA, disability policies after shorter-term sickness are focussed on strict medical and occupational requirements to be eligible for long-term disability benefits and/or for work interventions. Frequently, the physicians’ role in these countries is to assess these requirements for receiving ‘compensation for the injury’ or access to care [27]. However, to distinguish full from partial and permanent from temporary disability is notoriously difficult and causes confusion and injustice [8]. A recent qualitative study showed that such policies directed on judging the eligibility for claims, do not stimulate claimants to return to work [28]. In addition, these policies could induce claimants to adopt a ‘sick role’ to prove their pain is real [27].

In few countries, like the Netherlands, disability policies are primarily based on reintegration measures with no or few medical or occupational requirements for entitlement to long-term and partial benefits and occupational rehabilitation. The rationale of these policies is that less disagreement between claimants, employers and insurers creates a safe and secure workplace environment for RTW without risk of losing benefits. This could explain the high rate of work interventions and success in preventing work disability due to LBP in the Netherlands [29]. This rationale is also recently supported by the OECD: People do not return to work if they risk the loss of their benefits and risk denial of access to (occupational) health care; this contributes to very low outflow rates from disability benefits [8].

The main implication of our study is that a policy change is needed to encourage more work interventions supported by less strict compensation policy policies for entitlement to long-term and partial disability benefits. In order to achieve such a policy change, a collaborative action is needed by politicians and stakeholders at the workplace [30–32]. Hadler formulated it recently as the ‘important legacy from the twentieth century’s debacle with back injury’: “Even more important than a workplace that is comfortable when workers are well and accommodating when they are ill, is a workplace that appreciates each individual’s humanity: the need to be valued, the need to feel secure, the need for some autonomy, and the need to see a future. ‘Human capital’ deserves no less” [9].

References

Waddell G, Aylward M, Sawney P. Back pain, incapacity for work and social security benefits: an international literature review and analysis. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 2002.

Anema JR, van der Beek AJ. Medically certified sickness absence. BMJ. 2008;337:825–6.

Choosing health: making healthier choices easier. London: Department of Health. 2004.

Towards a better understanding of sickness absence costs. Dorking: Unum Limited, Institute for Employment Studies. 2001.

Blum F, Burton JF. Workers’ compensation costs in 2005: regional, industrial, and other variations. Work Compens Policy Rev. 2006;6:3–20.

Hashemi L, Webster BS, Clancy EA. Trends in disability duration and costs of workers’ compensation low back pain claims (1988–1996). J Occup Environ Med. 1998;40:1110–9.

Volinn E, Nishikitani M, Volinn W, Nakamura Y, Yano E. Back pain claim rates in Japan and the United States: framing the puzzle. Spine. 2005;30:697–704.

OECD. Transforming disability into ability. Polices to promote work and income security for disabled people. OECD. 2003. OECD Code 812003021P1; ISBN: 92-641-988-73.

Hadler NM, Tait RC, Chibnall JT. Back pain in the workplace. JAMA. 2007;297:1594–6.

Anema JR, van der Giezen AM, Buijs PC, van Mechelen W. Ineffective disability management of doctors is an obstacle for return-to-work. A cohort study on low back pain patients sicklisted for 3–4 months. Occup Environ Med. 2002;59:729–33.

A new deal for welfare: Empowering people to work. Colegate, UK: Department for Work and Pensions; 2006. http://www.dwp.gov.uk/welfarereform/docs/A_new_deal_for_welfare-Empowering_people_to_work-Full_Document.pdf. Accessed 24 January 2006.

Snashall D. Health of the working age population. New report recommends integration of occupational health into mainstream health care. BMJ. 2008;336:682.

Waddell G, Burton AK, Aylward M. A biopsychosocial model of sickness and disability. AMA guides newsletter. Chicago: American Medical Association; 2008. p. 1–13.

Main CJ, Williams AC. Musculoskeletal pain. BMJ. 2002;325:534–7.

van der Giezen AM, Bouter LM, Nijhuis FJ. Prediction of return-to-work of low back pain patients sicklisted for 3–4 months. Pain. 2000;87:285–94.

Bloch FS, Prins R. Who returns to work and why? A six country study on work incapacity and reintegration, vol. 5. New Brunswick: International Social Security Series; 2001.

Hansson TH, Hansson EK. The effects of common medical interventions on pain, back function, and work resumption in patients with chronic low back pain: a prospective 2-year cohort study in six countries. Spine. 2000;25:3055–64.

Anema JR, Cuelenaere B, van der Beek AJ, Knol DL, de Vet HCW, van Mechelen W. The effectiveness of ergonomic interventions on return-to-work after low back pain: a prospective 2-year cohort study in 6 countries on low back pain patients sicklisted 3–4 months. Occup Environ Med. 2004;61:289–94.

Wolf J, Cuelenaere B. Technical guide to the international database T1 to T3. Study on Work Incapacity and Reintegration (WIR) project. Hamburg: International Social Security Association Research Programme; 2000.

Kent JT, O’Quigly J. Measures of dependence for censored survival data. Biometrika. 1988;75:525–34.

Cassidy JD, Carroll LJ, Côté P, Lemstra M, Berglund A, Nygren A. Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1179–86.

Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Côté P, Berglund A, Nygren A. Low back pain after traffic collisions: a population-based cohort study. Spine. 2003;28:1002–9.

Cassidy JD, Carroll L, Côté P, Holm L, Nygren A. Mild traumatic brain injury after traffic collisions: a population-based inception cohort study. J Rehabil Med. 2004;43(Suppl):15–21.

Loisel P, Abenhaim L, Durand P, Esdaile JM, Suissa S, Gosselin L, et al. A population-based, randomized clinical trial on back pain management. Spine. 1997;22:2911–8.

Anema JR, Steenstra IA, Bongers PM, de Vet HC, Knol DL, Loisel P, et al. Multidisciplinary rehabilitation for subacute low back pain: graded activity or workplace intervention or both? A randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2007;32:291–8.

Wyatt M, Underwood MR, Scheel IB, Cassidy JD, Nagel P. Back pain and health policy research: the what, why, how, who, and when. Spine. 2004;29:E468–75.

Hadler NM. Workers with disabling back pain. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:341–3.

Lippel K. Workers describe the effect of the workers’ compensation process on their health: a Québec study. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30:427–43.

Steenstra IA, Verbeek JH, Prinsze HJ, Knol DL. Changes in the incidence of occupational disability as a result of back and neck pain in the Netherlands. BMC Public Health. 2006;18:6–190.

Loisel P, Buchbinder R, Hazard R, Keller R, Scheel I, van Tulder M, et al. Prevention of work disability due to musculoskeletal disorders: The challenge of implementing evidence. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15:507–24.

Schultz IZ, Stowell AW, Feuerstein M, Gatchel RJ. Models of return to work for musculoskeletal disorders. J Occup Rehabil. 2007;17:327–52.

Frank J, Sinclair S, Hogg-Johnson S, et al. Preventing disability from work-related low-back pain. New evidence gives new hope—if we can just get all the players onside. Can Med Assoc J. 1998;158:1625–31.

Acknowledgments

We thank AStri group for the scientific co-ordination of this multinational study and all participants in the Work Incapacity and Reintegration project for their contributions to this study. We thank the International Social Security Association (ISSA) for initiating this study. We are indebted to Dirk L Knol PhD for statistical advice. We thank the IEA Data Processing Centre, Hamburg, Germany for the data. Research Center for Insurance medicine AMC-UWV-VU University Medical Center, Amsterdam, the Netherlands is a joint initiative of Academic Medical Center, National Institute for Employment Benefit Schemes (UWV), and VU University Medical Centre. Contributors: The authors declare that they participated in the study and made the following contributions to the study and that I have seen and approved the final version. TJV contributed to the conception and design of this study. JRA and AJMS contributed to the analysis and JRA, AJMS, JDC, PL, TJV and AJvdB to the writing up of this study. JRA, AJMS and AJvdB will act as guarantors of this study. The corresponding author (JRA) had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. They declare that they have no competing interests. Funding sources: Social Security Supervisory Board, the Netherlands Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment and the Netherlands Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sports, with a grant from the General Disability Funds (now: UWV). JDC is partially funded by a Centre of Research Expertise grant from the Ontario Workplace Safety and Insurance Board. JRA and AJMS are (partially) funded by the Dutch Employee Benefit Schemes. The study sponsors had no (decisive) role in study design, in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication. All the patients reported in this study, gave a written informed consent. The design of this cohort study was observational and for data collection only questionnaires were used. Consequently, an ethics committee was not involved.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Anema, J.R., Schellart, A.J.M., Cassidy, J.D. et al. Can Cross Country Differences in Return-to-Work After Chronic Occupational Back Pain be Explained? An Exploratory Analysis on Disability Policies in a Six Country Cohort Study. J Occup Rehabil 19, 419–426 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9202-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10926-009-9202-3