Abstract

There is a rapidly evolving need for e-health to support chronic disease self-management and connect patients with their healthcare teams. Patients with cirrhosis have a high symptom burden, significant comorbidities, and a range of psychological and cognitive issues. Patients with cirrhosis were assessed for their readiness and interest in e-health. Adults attending one of two outpatient cirrhosis clinics in Alberta were recruited. Eligible participants were not required to own or have experience with digital technologies or the Internet. Medical history, socioeconomic status, and attitudes regarding e-health, the Computer Proficiency Questionnaire, and the Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire were used to describe participants’ knowledge and skills. Of the 117 recruited patients, 68.4% owned a computer and 84.6% owned a mobile device. Patients had mean proficiency scores of 72.8% (SD 25.9%) and 69.3% (SD 26.4%) for these devices, respectively. In multiple regression analyses, significant predictors of device proficiency were age, education, and household income. Most patients (78.7%) were confident they could participate in videoconferencing after training and most (61.5%) were interested in an online personalized health management program. This diverse group of patients with cirrhosis had technology ownership, proficiency, and online behaviours similar to the general population. Moreover, the patients were very receptive to e-health if training was provided. This promising data is timely given the unique demands of COVID-19 and its influence on self-management and healthcare delivery to a vulnerable population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

All chronic liver diseases eventually progress to cirrhosis, a common endpoint where the accumulation of scar tissue causes portal hypertension-related complications and impedes normal liver function. Patients with compensated cirrhosis have a median survival time greater than 12 years [1]. Once the liver progresses to the decompensated state, indicated by complications such as ascites, hepatic encephalopathy (HE), or variceal bleeding, the median survival decreases to approximately two years [1]. Across the cirrhosis trajectory, patients receive complex medical care involving preventative screening (e.g., cancer, varices), treating complications, and managing their high symptom burden, including but not limited to pain, fatigue, and depression [2,3,4].

E-health solutions (e.g., websites, telemonitoring, mobile apps designed to perform specific functions) to support patient self-management and health services have been introduced in many chronic disease populations, such as cardiovascular diseases, fibromyalgia, Parkinson’s disease, chronic kidney disease, HIV, cancer, and mental illness [5,6,7,8,9]. In cirrhosis, the “Patient Buddy” app has been created for individuals with a history of hepatic encephalopathy [10]. The term “e-health” is used as both a noun and verb indicating the intersection of health, information, communication technology, and various stakeholders [11]. E-health has been associated with improvements in general self-management skills, communications with healthcare professionals, quality of life, physical function, pain management, and health outcomes [5].

An underlying assumption of e-health is that users have ready access to Internet-connected digital technology and the skills to use it effectively. The reality is that the “digital divide” persists along lines of social inequalities (i.e., education, urban versus rural, income, age, and immigration status [12,13,14]) and influences the access and the ability to use e-health. Two barriers are common in cirrhosis, prevalence of low socioeconomic status [15,16,17] and that nearly one third of patients are 65 years or older [18]. From a patient’s perspective, additional barriers may include cirrhosis severity, physical disabilities, or cognitive abilities [19, 20].

The purpose of this study was to characterize the readiness of patients with cirrhosis for e-health by: (1) assessing their Internet access frequency and digital technology ownership; (2) determining their digital literacy proficiency and identifying relevant predictors; and, (3) ascertaining their general attitudes and receptiveness to video conferencing and online health management programs by age group. Aims 1 and 2 considered the severity of cirrhosis as indicated by the Child-Pugh score [21, 22]. By understanding the skills and preferences of patients with cirrhosis, e-health solutions can be better designed to meet their unique needs and abilities. In turn, these e-health products may achieve a wider adoption and longer period of use leading to improved patient health outcomes [23].

Methods

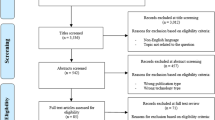

A survey-based, cross-sectional study was used to capture self-reported information regarding computer and Internet proficiency and attitudes in patients living with cirrhosis. The study was approved by the Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Alberta (Pro00082756). A convenience sample of consecutively consenting patients was recruited from outpatient liver clinics at two tertiary care hospitals located in western Canada from July 2018 to February 2019.

Participants

Eligibility criteria required that participants be: 18 years of age or older; have a confirmed diagnosis of cirrhosis as determined by imaging, medical history, transient elastography, or liver biopsy; could provide informed written consent; and, could read and write in English. Ineligible participants were transplant recipients or individuals who were unable to provide consent. There was no requirement for having previous digital technology or Internet access. This study had an intended enrollment target of 125 participants based upon previous studies of this kind [24,25,26].

Procedure

After written informed consent was obtained, patients were asked to complete a survey in a paper and pencil format to minimize bias regarding technology proficiency. It was completed in a clinic exam room. The research assistant remained nearby to answer questions and review the responses for completeness. If a patient asked the research assistant for a digital version of the survey, a link to an the online version was provided via REDCap [27].

Participant Characteristics

To characterize the cohort, each participant's personal health number was used to access their electronic health records: age (years), biological sex, liver disease etiology, prognostic measures (model for end-stage liver disease-sodium [MELD-Na] [28] and the Child-Pugh score, both determined with the patient’s most recent blood tests), history of HE, cancer history, significant comorbidities, disabilities, and current medications. Patients completed a general survey about their level of education, household income, digital technology devices they owned, frequency of Internet use, and online communication preferences.

Outcome Measures

The Computer Proficiency Questionnaire (CPQ) captures information about the patient’s computer and Internet skills [23]. The CPQ contains six domains assessing skills regarding computer basics, printing, communication, Internet, calendar, and entertainment. The Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire (MDPQ) characterizes the patient’s skills with smart devices across eight domains: mobile device basics, communication, data and file storage, Internet, calendar, entertainment, privacy, and troubleshooting and software management [20]. The CPQ and MDPQ used a 5-point Likert scale (1=never tried; 2=not at all; 3=not very easily; 4=somewhat easily; and 5=very easily) and the questionnaires were scored as previously described [20, 23]. The total possible points for the CPQ and MDPQ were 30 and 40, respectively. These validated questionnaires have demonstrated significant relationships with the length and frequency of use of a specific technology [20]. Internal consistency for each scale is high with Cronbach’s α≥.98 [20, 23, 29].

A third questionnaire captured patient receptiveness about video calling with healthcare professionals (see Supplemental-Fig. 1). It was developed in-house for this study and was not validated before use. Patient responses to each of the seven statements were answered with a Likert scale: 1=totally disagree, 2=somewhat disagree, 3=neutral, 4=somewhat agree, and 5=totally agree. Online delivery of healthcare programming was explored with the question “If our team provided you with the training to make you more comfortable with using the Internet, how interested would you be in participating in a personalized health management program delivered by an Internet-based app (e.g., receiving exercise information, dietary information, reminders, and motivational tips)?” Patient preferences regarding four discrete functional elements for the hypothetical personalized online program were captured with a 5-point Likert scale: 1=not helpful at all, 2=somewhat unhelpful, 3=neutral, 4=somewhat helpful, and 5=extremely helpful (see Supplemental-Fig. 2).

Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, median, frequency) were generated for participants organized by Child-Pugh (CP) classification (A vs. B/C). Between group comparisons were completed for categorical variables using the χ2 test or Fisher exact test, for continuous variables using independent samples t test, and ordinal variables using the Mann Whitney U test. Correlation analyses between CPQ and MDPQ scores and the continuous variables of age, CP score, and MELD-Na score were completed. To construct the regression models, significant variables (p<0.05) from the correlational analysis were included with dichotomous (sex, HE, comorbidities, visual impairment) and categorical (cirrhosis etiology, household income, education) variables and then regressed against either CPQ or MDPQ. Non-significant predictors were eliminated manually one by one and the regression was rerun. Only variables that significantly contributed to the models were retained. When assessing attitudes and preferences regarding video calling and online programming, the Kruskal-Wallis H test was used to determine if age differences existed. Specifically, with alpha set at p<.05, pairwise comparisons between the age groups were performed using Dunn's (1964) procedure with a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Missing survey data were obtained from the study participant. All analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

Results

Description of Participants

One hundred seventeen patients were recruited (age range: 24 to 83 years; MELD-Na score range: 6 to 33; Table 1) of which 72 (61.5%) were men. Significant differences were found between the two study groups (Child-Pugh A versus B/C) for mean MELD-Na score, ascites, diuretics, and lactulose and/or rifaximin (p >.001 for each) which were consistent with cirrhosis severity. Many patients had significant comorbidities: diabetes (n=36; 30.8%); arthritis (n=33; 28.2%); any cancer (n=33; 28.2%); asthma, (n=14; 12.0%); or, myocardial infarction (n=10; 8.5%). A total of 14 (12.0%) participants reported a visual impairment. More than half of the respondents had attended post-secondary education (e.g., college, professional courses).

Digital Technology Ownership and Internet Behaviours

Participants’ responses to questions regarding their digital technology ownership, Internet access, attitudes are presented in Table 2. Disease severity indicated by Child-Pugh scores (A vs B/C) was not associated with any of the relevant variables. From a list of 10 common digital technology devices, 90 (76.9%) patients owned a smartphone. This was followed by ownership of laptops (53.8%), desktop computers (48.7%), tablets (43.6%), and smart televisions (31.6%) which are Internet connected and function like a television and computer. Only one patient stated that they did not own any of the devices. Nine (7.7%) patients did not own a smart device nor a computing system while 71 (60.7%) owned both. Daily Internet use was reported by 72 (61.5%) patients. Only 14 (12.0%) patients had never accessed the Internet. The Internet was accessed either frequently or very frequently for communication purposes by 69 (59.0%) patients. One hundred (85.5%) patients reported that digital technology was most helpful for communicating with others. Though only 52 (44.0%) patients used the Internet frequently or very frequently to obtain information, 78.6% stated that digital technology helped them to make more informed decisions. In all, 82.9% stated that life was better because of digital technology use.

Digital Technology Proficiency

Since the CPQ and MDPQ assess technology proficiency in four of the same areas (communication, Internet, calendar, and entertainment), and a strong positive correlation (r=0.93) was observed between the two sets of scores.

Common markers for disease severity (e.g., the MELD-Na score, Child-Pugh score) were not related to either the CPQ or MDPQ. The only significant correlate was age which was included in the subsequent multiple regression analyses. The final CPQ model explained 40% of the variance (adjusted R2 = 0.403), F(6, 110)=14.071, p<0.001 (Table 3). Educational background impacted CPQ scores where graduates from grade 8 or high school had lower scores (26.4% and 23.3%, respectively) than their post-secondary peers. Age had a significant influence in the multiple regression model where each year of life changed the CPQ score by -0.8% (reducing proficiency). For the household income variable, only the sub-category of less than $25,000 significantly influenced the CPQ by -10.8% (p=.02). These variables were also significant correlates for the MDPQ model with no difference in direction of influence of the predictors and no additional predictors identified (Table 3). When examining the effect size of the predictors for the CPQ and MDPQ, the patient age variable (partial η2=.17 and partial η2=.25, respectively) outperformed education considering its cumulative yearly impact and the mean age of the study population of 58.2 years.

Video Calling Preferences

Figure 1 presents the responses to questions regarding patient opinions about this online form of communication. Most patients were receptive to using video calling with health care professionals and only 16 (13.7%) were totally against it. Seventy-nine (67.5%) patients expected that video calling with a healthcare professional would be confidential. Patients expected that video calling would be both quick to learn and easy to do thereafter. Seventy-seven (65.8%) patients agreed that video calls with healthcare professionals would be associated with a safe feeling. When asked if they could make video calls on their own, only 25 (29.1%) patients totally agreed. When asked if they were provided with training, 56 (47.9%) patients totally agreed that they could use video calling.

To determine the impact of patient age on their video calling preferences, a Kruskal-Wallis H test was run with patients categorized into three groups: Group A, 24-55 years (n=40); Group B, 56-63 years (n=39); and, Group C, 64-83 years (n=38). Patient age had a significant impact on responses for questions 1, 3, 4, and 6 (see Fig. 1 for survey results). Younger patients (Group A) were more receptive and positive about the use of video calling with healthcare professionals than older patients in Groups B or C (see Supplemental-Table 1 for pairwise comparison details).

Online Personalized Exercise Program Preferences

Regarding interest in an online personalized health management program, 72 (61.5%) patients were somewhat or very interested, 12 (10.2%) were neutral, 21 (17.9%) were somewhat or very disinterested, and 12 (10.2%) did not know. Patient responses to the four elements of the online program (e.g., video content and motivational messaging) ranged across the entire Likert scale; a considerable proportion (range: 21.3% to 36.7%) of respondents did not consider these as helpful (see Fig. 2 for survey results). A single element was neither favoured nor disliked by the entire study group. The Kruskal-Wallis H test identified that preferences about text messaging motivational tips were significantly impacted by patient age with younger patients preferring it more than older ones (Group A vs Group C; see Supplemental-Table 2 for pairwise comparison details).

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating digital literacy skills, Internet access, and digital technology preferences of patients with cirrhosis. Within our cohort, the main findings of this study were: (1) most patients owned or used technology in their homes with the majority accessing the Internet daily; (2) skills using either computers or mobile devices was moderate and significant predictors of proficiency were age, education, and household income less than $25,000 per year; and, (3) most were receptive to video calling with healthcare professionals and interested in online personalized health management programming.

Technology ownership in this cirrhosis study was similar to data presented in the Internet and digital technology component of the 2016 General Social Survey for Canada [30]: (smart device: 76% vs. 85%; computer: 71% vs. 68.4%, respectively). Our study participants reported that technology was even more useful for communication than the national average (86% vs. 77%, respectively), including its use to make informed decisions (79% vs. 52%, respectively) be more creative (64% vs. 36%, respectively). Overall, 83% of study patients believed that life was better because of technology versus 60% for Canadians of a similar age range. The median household income for the study group of $25,000 to $50,000 was below the average for the Edmonton region ($87,225) and province ($93,835) [31]. Despite limited finances, study patients had similar rates of technology ownership, Internet habits, and attitudes as other Canadians. This suggests that study participants value Internet and communications technology and financially prioritize these. Interestingly, when participants were grouped by their Child-Pugh score, no significant differences were found suggesting that these behaviours may be independent of cirrhosis severity.

The scores on the computer and mobile device proficiency questionnaires (CPQ and MDPQ, respectively) indicate that patients had moderate proficiency with these technologies. For comparison, one study reported a mean CPQ score of 33.3% (n=276) was attained by people with minimal computer experience while a mean score of 81.2% (n=76) was associated with several years of computer experience and computer ownership in older adults [23]. A second study reported a mean CPQ score of 78.2% for 116 adults from the general population [29]. MDPQ scores have been significantly correlated with both the length and frequency of use of mobile devices in adults (n=95) [20]. Specifically, MDPQ scores for the general population have ranged between 48% to 92% in the United States [20] and 33% to 90% in Spain [29]. Overall, our study patients had computer and mobile device proficiencies comparable to their healthy counterparts.

Measures of cirrhosis severity (MELD-Na, CP score), comorbidities, history of HE, and visual impairments were not significant predictors of either CPQ or MDPQ scores. However, the well-described barriers of age, education, and income impacted digital technology proficiency [24, 26, 32, 33], were significant predictors for our cirrhosis study group. Within the limits of our sample, this suggests that there are no unique digital divide barriers specific to cirrhosis.

Although descriptive studies have indicated that cognitive decline and episodic memory are barriers to both technology adoption and Internet use, two studies have found evidence suggesting other elements are involved [24, 26]. In addition to age and education, they found other predictors of technology proficiency: sense of control, inductive reasoning, perceptual speed, and psychomotor speed. They hypothesized that these additional predictors could compensate for cognitive and memory issues [24, 26]. Similarly, a history of HE was not a significant predictor of either CPQ or MDPQ scores. Notably, these patients were on lactulose or rifaximin as per practice guidelines [34], and detailed cognitive testing was not carried out in the current study.

Patients with cirrhosis had positive perceptions and attitudes regarding video conferencing with healthcare professionals. For comparison, a 2016 study in England reported that only 50% of 270 adult patients attending one of three general practitioners’ clinics were willing to use video consulting [35]. In this study, patients expected that videoconferencing should be confidential, it would be quick to learn, and easy to do once they received training. These same factors influenced the intention to use video calling for 256 adults (median age: 71 years) who were living independently at home [36]. In cirrhosis, e-health involving video calling must meet the design and usability needs across a broad age spectrum (20-80+ years).

Though patients were receptive to a virtual personalized health management program, there was variation in their preferences for program content and functional features such as motivational tips. This suggests that for any e-health tool to be successful, it needs to be customizable and offer flexible options for interaction with the user. In addition to adequate training, it was clear that patients also wanted to engage with the virtual program on terms that best suited their perceived needs and interests.

Strengths and Limitations

A study strength is that patients were recruited from three different clinic environments - a tertiary care outpatient liver clinic at an academic hospital, a liver transplant clinic and an outpatient clinic affiliated with an inner-city tertiary care hospital. This ensured that participants came from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds, residential locations, and health experiences thereby supporting the generalizability of the results, except to those at the extremes of homelessness and poverty. Though the CPQ and MDPQ have been validated, they rely on self-reported skills and may not be reflective of a person’s true ability. Though we did not have the infrastructure and resources to do so, a more direct evaluation of digital literacy proficiencies would be to watch a patient perform tasks in real-time. Commercial online proficiency tests are available but extensive customization of the proprietary software is required for research making them impractical [37]. As inclusion criteria required English language proficiency, the results cannot be generalized to non-English speakers.

Though we were able to explore the influence of many cirrhosis-related and general health-related factors on computing and mobile device proficiencies, it was beyond the scope of the study to explore the predictive characteristics that correlated with CPQ scores, such as inductive reasoning, perceptual speed, and psychomotor speed [24, 26]. Our rationale for selecting the CPQ and MDPQ was their specificity for evaluating computing and mobile device skills, ease of assessment, and currency in consideration of the rapid changes in digital technology and Internet behaviours.

In conclusion, we found that patients living with cirrhosis are ready for e-health a long as it is provided alongside adequate training and support. The recent successes of e-health suggest that it will no doubt persist beyond the current pandemic [38, 39]. Only by building upon past work and integrating useful frameworks (i.e., Technology Evaluation and Assessment Criteria for Health apps [40]) will e-health solutions effectively improve patient care and health outcomes. It is becoming apparent that society is rapidly moving into an era where e-health access and possessing a minimum of technology skills are becoming basic necessities rather than a luxury or lifestyle choice. For the cirrhosis population, results of this study show that e-health strategies offer promising opportunities to support patient management and healthcare.

Abbreviations

- HE:

-

hepatic encephalopathy

- MELD-NA:

-

model for end stage liver disease – sodium

- CPQ:

-

Computer Proficiency Questionnaire

- MDPQ:

-

Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire

- CP:

-

Child-Pugh score

References

D'Amico G, Garcia-Tsao G, Pagliaro L. Natural history and prognostic indicators of survival in cirrhosis: a systematic review of 118 studies. J Hepatol. 2006;44(1):217-231.

Janani K, Jain M, Vargese J, et al. Health-related quality of life in liver cirrhosis patients using SF-36 and CLDQ questionnaires. Clin Exp Hepatol. 2018;4(4):232-239.

Marchesini G, Bianchi G, Amodio P, et al. Factors associated with poor health-related quality of life of patients with cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 2001;120(1):170-178.

Martin LM, Sheridan MJ, Younossi ZM. The impact of liver disease on health-related quality of life: a review of the literature. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2002;4(1):79-83.

Lee J-A, Choi M, Lee SA, Jiang N. Effective Behavioral Intervention Strategies Using Mobile Health Applications for Chronic Disease Management: A Systematic Review. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2018;18(1):12.

Stevenson JK, Campbell ZC, Webster AC, et al. eHealth interventions for people with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;8(8):Cd012379.

Penedo FJ, Oswald LB, Kronenfeld JP, Garcia SF, Cella D, Yanez B. The increasing value of eHealth in the delivery of patient-centred cancer care. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(5):e240-e251.

Triberti S, Savioni L, Sebri V, Pravettoni G. eHealth for improving quality of life in breast cancer patients: A systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev. 2019;74:1-14.

Naslund JA, Marsch LA, McHugo GJ, Bartels SJ. Emerging mHealth and eHealth interventions for serious mental illness: a review of the literature. J Ment Health. 2015;24(5):321-332.

Ganapathy D, Acharya C, Lachar J, et al. The patient buddy app can potentially prevent hepatic encephalopathy-related readmissions. Liver Int. 2017;37(12):1843-1851.

Meier CA, Fitzgerald MC, Smith JM. eHealth: extending, enhancing, and evolving health care. Annu Rev Biomed Eng. 2013;15:359-382.

Scheerder A, van Deursen A, van Dijk J. Determinants of Internet skills, uses and outcomes. A systematic review of the second- and third-level digital divide. Telematics and Informatics. 2017;34:1607-1624.

Beaunoyer E, Dupere S, Guitton MJ. COVID-19 and digital inequalities: reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior. 2020;111:106424.

Haight M, Quan-Haase A, Corbett BA. Revisiting the digital divide in Canada: the impact of demographic factors on access to the internet, level of online activity, and social networking site usage. Information, Communication & Society. 2014;17(4):503-519.

Axley PD, Richardson CT, Singal AK. Epidemiology of Alcohol Consumption and Societal Burden of Alcoholism and Alcoholic Liver Disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2019;23(1):39-50.

Jones L, Bates G, McCoy E, Bellis MA. Relationship between alcohol-attributable disease and socioeconomic status, and the role of alcohol consumption in this relationship: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:400.

Singh GK, Hoyert DL. Social epidemiology of chronic liver disease and cirrhosis mortality in the United States, 1935-1997: trends and differentials by ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and alcohol consumption. Hum Biol. 2000;72(5):801-820.

Orman ES, Roberts A, Ghabril M, et al. Trends in Characteristics, Mortality, and Other Outcomes of Patients With Newly Diagnosed Cirrhosis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e196412.

Hargittal E, Piper AM, Ringel Morris MR. From Internet access to Internet skills: digital inequality among older adults. Univ Access Inf Soc. 2019;18:881-890.

Roque NA, Boot WR. A new tool for assessing mobile device proficiency in older adults: the Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaire. J Appl Gerontol. 2018;37(2):131-156.

Pugh RN, Murray-Lyon IM, Dawson JL, Pietroni MC, Williams R. Transection of the oesophagus for bleeding oesophageal varices. Br J Surg. 1973;60(8):646-649.

Child CG, Turcotte JG. Surgery and portal hypertension In: Child CG, ed. The Liver and Portal Hypertension. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1964:50-64.

Boot WR, Charness N, Czaja SJ, et al. Computer proficiency questionnaire: assessing low and high computer proficient seniors. The Gerontologist. 2015;55(3):404-411.

Champagne K, Boot WR. Exploring predictors of mobile device proficiency among older adults. In: Kurosu M, ed. Human-Computing Interaction 2017, Part II. Springer International Publishing; 2017:162-171.

Mitzner TL, Savla J, Boot WR, et al. Technology Adoption by Older Adults: Findings From the PRISM Trial. The Gerontologist. 2019;59(1):34-44.

Zhang S, Grenhart WCM, Collins McLaughlin A, Allaire JC. Predicting computer proficiency in older adults. Comput Human Behav. 2017:106-112.

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377-381.

Kim WR, Biggins SW, Kremers WK, et al. Hyponatremia and mortality among patients on the liver-transplant waiting list. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(10):1018-1026.

Moret-Tatay C, Beneyto-Arrojo MJ, Gutierrez E, Boot WR, Charness N. A Spanish Adaptation of the Computer and Mobile Device Proficiency Questionnaires (CPQ and MDPQ) for Older Adults. Front Psychol. 2019;10:1165.

Statistics Canada. The internet and digital technology. Catalogue no. 11-627-M. 2017; https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-627-m/11-627-m2017032-eng.htm. Accessed February 1, 2021.

Statistics Canada. Edmonton, CY [Census Subdivision], Alberta. Census Profile. 2016 Census. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2016001 2017; https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/index.cfm?Lang=E. Accessed February 2, 2021.

Nguyen A, Mosadeghi S, Almario CV. Persistent digital divide in access to and use of the Internet as a resource for health information: Results from a California population-based study. Int J Med Inform. 2017;103:49-54.

Reiners F, Sturm J, Bouw LJW, Wouters EJM. Sociodemographic factors influencing the use of eHealth in people with chronic diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16(4):645.

Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, et al. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60(2):715-735.

Johnston S, MacDougall M, McKinstry B. The use of video consulting in general practice: semi-structured interviews examining acceptability to patients. J Innov Health Inform. 2016;23(2):493-500.

van Houwelingen CT, Ettema RG, Antonietti MG, Kort HS. Understanding older people's readiness for receiving telehealth: mixed-method study. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20(4):e123.

Olney AM, Bakhtiari D, Greenberg D, Graesser A. Assessing computer literacy of adults with low literacy skills. JEDM. 2017:128-134.

Su GL, Glass L, Tapper EB, Van T, Waljee AK, Sales AE. Virtual Consultations Through the Veterans Administration SCAN-ECHO Project Improves Survival for Veterans With Liver Disease. Hepatology. 2018;68(6):2317-2324.

Tapper EB, Asrani SK. The COVID-19 pandemic will have a long-lasting impact on the quality of cirrhosis care. J Hepatol. 2020.

Camacho E, Hoffman L, Lagan S, et al. Technology Evaluation and Assessment Criteria for Health Apps (TEACH-Apps): Pilot Study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e18346.

Funding

This study was funded in part by the Canadian Donation and Transplant Research Program awarded to P Tandon. KP Ismond received funding from Mitacs in conjunction with unrestricted funding from Lupin Pharma Canada Ltd. and Astellas Pharma Canada, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KPI and PT planned and conducted the study, TE and KF collected data with assistance of MS and RJB. Data analyses and interpretation involved KP, JCS, JA, JS, and PT. Manuscript drafted by KPI and all contributed critical edits and feedback.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Statement of Interests

The authors have no declarations of personal interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Patient Facing Systems

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ismond, K.P., Eslamparast, T., Farhat, K. et al. Assessing Patient Proficiency with Internet-Connected Technology and Their Preferences for E-Health in Cirrhosis. J Med Syst 45, 72 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-021-01746-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10916-021-01746-3