Abstract

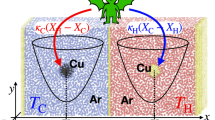

We consider the refrigeration of an array of heat-dissipating cylindrical nanosystems as a simplified model of computer refrigeration. We explore the use of He II as cooling fluid, taking into account forced convection and heat conduction. The main conceptual and practical difficulties arise in the calculation of the effective thermal conductivity. Since He II does not follow Fourier’s law, the effective geometry-dependent conductivity must be extracted from a more general equation for heat transfer. Furthermore, we impose the restrictions that the maximum temperature along the array should be less than \(T_{\lambda }\) transition temperature and that quantum turbulence is avoided, in order not to have too high heat resistance.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Refrigeration of arrays of heat-dissipating nanodevices by means of superfluid helium is a particular problem of cryogenics [1] both for cooling nanoelectronic and nanomechanical devices down to millikelvin and sub-millikelvin temperatures, as recently performed in laboratories and in aerospatial cryogenics, and for representing a potential future interest in computer refrigeration, as for instance in quantum computers which require a high extent of quantum coherence of the global wave function for qubits [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9], achieved at very low temperature.

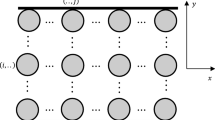

In a previous paper [10] we considered, as a simplified model, the refrigeration of a regular array of cylindrical heat-dissipating nanodevices immersed in superfluid helium between two parallel plates. The main difficulty of the problem was finding the effective heat conductivity for helium counterflows [11,12,13,14] (heat transport without net mass transport), in the laminar regime (namely without any kind of turbulence), which strongly depends on the geometry of the problem, in contrast with usual Fourier’s law, where thermal conductivity is a material coefficient independent of the geometry. The effective thermal conductivity was determined for both dilute and dense arrays of nanocylinders, perpendicular to the walls of the channel, and we computed the maximum heat which could be removed per unit time under the restriction of avoiding quantum turbulence.

The aim of the present paper is to incorporate the role of a forced convective helium flow (also called co-flow) in removing the dissipated heat. The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2, the basic equations of the problem are presented, with special emphasis on the equation for heat transport in He II, which is much more general than Fourier’s law. In Sect. 3, the results for the total effective thermal conductivity in different geometries are given, with and without the arrays of hot cylinders. In Sect. 4, the discrete algorithm for the temperature profile in the lattice of dissipating cylinders is discussed.

2 Basic Equations for Heat Transfer in Superfluid Helium

We aim to consider heat removal from the system by means of forced He II convection with net velocity \(\mathbf{v}\). The basic equations for the specific volume (volume per unit mass) \(V=\rho ^{-1}\), the velocity \({\mathbf {v}}\), the specific internal energy \(\epsilon \) and heat flux \({\mathbf {q}}\) are [15,16,17,18]

where S is the entropy per unit volume, p pressure, T temperature, \(\rho \) the total mass density, \(\tau \) the relaxation time of \({\mathbf {q}}\), \(\lambda _1\) and \(\eta \) can be interpreted as the thermal conductivity and the shear viscosity, respectively, when applied to a classical fluid [17], the ratio \(\lambda _1/\tau \) is related to the second-sound speed, and L is the vortex length density, describing the presence of quantized vortices in the turbulent regime. The last two Eqs. (3) and (4) can be related to the hydrodynamical equations for the fields \({\mathbf {v}}_n\) and \({\mathbf {v}}_s\) (the normal and superfluid components in the two-fluid model [19]) by \({\mathbf {v}}_s= {\mathbf {v}}-\frac{\rho _n}{\rho _s}\frac{1}{\textit{TS}} {\mathbf {q}}\) and \({\mathbf {v}}_n= {\mathbf {v}}+\frac{1}{\textit{TS}} {\mathbf {q}}\), \({\mathbf {v}}\) and \({\mathbf {q}}\) being more directly measurable than \({\mathbf {v}}_n\) and \({\mathbf {v}}_s\).

Equation (1) has been written in terms of the volume V instead of the usual density \(\rho \) for future purposes. Since we want to avoid quantum turbulence, we will take \(L=0\) in Eq. (4); otherwise, an additional evolution equation for L should be included in (1)–(4). The source term \(\sigma ^{\epsilon }\) corresponds to the supplies of internal energy acting on the system. In our case, they represent the heat-dissipating nanodevices whose heat we want to remove from the system, in order to avoid an excessive increase of temperature, which could damage the system or reduce its efficiency.

In (1)–(4) the upper dot stands for material derivatives, i.e., \(\displaystyle \frac{\partial }{\partial t}+({\mathbf {v}}\cdot \nabla )\). Combining (1) and (2) at constant pressure one obtains

with \(h=\epsilon +pV\) being the specific enthalpy of helium II. In Eq. (5), \(\sigma ^{\epsilon }\) is given by the particular system we want to refrigerate, and the main physical challenge is to obtain \({\mathbf {q}}\), which is the heat transported inside the system by conduction, or by internal convection.

Indeed, heat transport in He II is not described by Fourier’s law, but by a more complex equation, including non-local terms, strongly depending on the geometry and the size of the particular system being considered. Heat transport can be investigated in laminar regime, in fully turbulent regime, in the ballistic regime, or in the transition from laminar to turbulent regimes [10, 18,19,20,21]. In the laminar regime, one has for the average heat flux

where \(K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}\) is the effective thermal conduction, depending of the size and the geometry, which is obtained by integration of (3) and (4) over the suitable geometry, thus yielding \(K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}\). On the other hand, in the fully turbulent regime one has \({\mathbf {q}}\sim \left( \nabla T\right) ^{\frac{1}{3}}\) (Görter-Mellink regime).

In [18,19,20,21] heat transport in He II was studied in the laminar, turbulent and ballistic regimes as well as in the intermediate regimes, obtaining an expression of \(\mathbf{q}\) of the form (6) by starting from Eq. (4). Here, as in [10], we want to consider the laminar regime in order to avoid quantum turbulence, which reduces the efficiency of heat removal [18].

3 Derivation of Effective Thermal Conductivity

In this section, we briefly review past results obtained for Helium counterflows illustrated in Ref. [10]. In the steady state, Eqs. (3) and (4) read as follows

where the term of the order of \(1/\lambda _1\) is neglected in Eq. (4) due to the fact that \(\lambda _1,\tau \gg 1\) and their ratio \(\lambda _1/\tau \) is finite.

In [10] we considered a laminar regime in a geometry where terms \(({\mathbf {v}}\cdot \nabla ){\mathbf {v}}\) and \(({\mathbf {v}}\cdot \nabla ){\mathbf {q}}\) are identically zero, as it occurs in the problem investigated in the present work. Hence, Eqs. (7) and (8) are reduced to

and \(S\nabla T=\nabla p\). Equation (9) is analogous to the equation for a Poiseuille flow of velocity \(\displaystyle {\mathbf {b}}\equiv {\mathbf {v}}+\frac{{\mathbf {q}}}{ST}\). Starting from Eqs. (7) and (8) and imposing the counterflow condition \(\bar{{\mathbf {v}}}=0\) (namely the average velocity across any transversal section of the channel is zero), in [10] we obtained the following expressions for the effective thermal conductivity \(K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}\) of a helium counterflow in a rectangular cross-sectional channel with dimensions \(x \in [0,l]\) (streamwise direction), \(y \in \left[ -\frac{a}{2},\frac{a}{2}\right] \) (spanwise direction), \(z \in [0,b]\) (vertical direction):

-

(a)

plane channel (without arrays of cylindrical nanodevices) [10, 20]

$$\begin{aligned} K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}= \frac{ab^3}{12}\left( \frac{S^2T}{\eta }\right) \left[ 1-\sum _{n,\mathrm {odd}}^{\infty }\frac{1}{n^5} \left( \frac{192}{\varphi \pi ^5}\right) \tanh \left( n\pi \frac{\varphi }{2}\right) \right] , \end{aligned}$$(10)which for \(\varphi =a/b\gg 1\) (thin and wide channels) reduces to

$$\begin{aligned} K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}= \frac{ab^3}{12}\left( \frac{S^2T}{\eta }\right) \left[ 1-\frac{0.63}{\varphi }\right] . \end{aligned}$$(11) -

(b1)

for transport through an array of cylindrical obstacles with narrow separation between cylinders [10]

$$\begin{aligned} K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}=\frac{1}{b\left( 1-\phi \right) } \left\{ \frac{12}{b^3\left( 1-\phi \right) \left( 1-\frac{0.63}{\varphi }\right) } +\frac{9\pi }{2bc^2}\left[ \frac{\phi ^2}{\left( 1-\phi ^2\right) ^{5/2}}\right] \right\} ^{-1}\left( \frac{S^2T}{\eta }\right) ,\nonumber \\ \end{aligned}$$(12)cylinders

$$\begin{aligned} K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}=\frac{1}{b\left( 1-\phi \right) } \left\{ \frac{12}{b^3\left( 1-\phi \right) \left( 1-\frac{0.63}{\varphi }\right) } + \frac{3}{bc^2}\left[ \frac{1}{\left( 1-\phi ^2\right) ^2}\right] \right\} ^{-1} \left( \frac{S^2T}{\eta }\right) ,\nonumber \\ \end{aligned}$$(13)

where \(\displaystyle \phi =R/c\) (R being the radius of the cylinder and 2c the distance between the axes of consecutive cylinders in such a way that \(2\left( c-R\right) \) is the separation between two consecutive cylinders, or between the cylinders and the walls). For such a system, narrow separation between cylinders means \(1-\phi \ll 1\Leftrightarrow \phi \rightarrow 1\), i.e., the spacing between the cylinders is much smaller than their cross-sectional dimensions; and wide separation between cylinders means \(\phi \ll 1\Leftrightarrow \phi \rightarrow 0\), i.e., the spacing between the cylinders is much bigger than their radius R.

The total effective thermal conductivity \(K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}^{\mathrm{{tot}}}\) for an array of cylinders inside a rectangular channel will combine (10), or (11), (denoted as \(K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}^{\mathrm{{(a)}}}\)) with (12) or (13) (denoted as \(K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}^{\mathrm{{(b)}}}\)) in parallel depending on the channel and the array we are considering:

This last expression has been obtained following the general lines of Ref. [10] by adding the contribution of two pressure gradients (arising from the presence of both channel walls and the array of cylinders), yielding the corresponding hydrodynamical resistance of He II, carrying the heat. Once we have the expression of the effective thermal resistance, we may solve in principle our problem.

4 Solution for the Temperature Profile

Let \(\dot{Q_i}'\) be the sum of the dissipated heat of all the cylinders in column i [i.e., \(\dot{Q_i}'=\sum _j \dot{Q_{ij}}'\), being \(\dot{Q_{ij}}'\) the heat dissipated by the (i, j) nanodevice, see Fig. 1]. In other words, the \(\sigma ^{\epsilon }\) describing the source terms in Eq. (2) is composed of all the cylinders in the column, i.e., it is a discretized term acting on the positions of the several cylinders.

In [10] it was assumed that heat was flowing by pure counterflow: Because of the symmetry of the system, it was flowing from \(i=0\) to \(i=N\) and to \(i=-N\) (the upper and lower boundaries were assumed to be insulating in our particular example, see Fig. 1 ). We obtained the steady-state temperature \(T_i\) of He II at the several positions \(i \in [-N,N]\) along the x-axis (in fact, He II is considered as a continuous system, and its temperature is defined over the whole continuous zone it is occupying, but for our purpose knowing the temperature of this discrete set of positions of the cylinder is sufficient to characterize the state of the system for practical needs).

In the present work, we employ the same strategy, but in the presence of forced helium convection with volume flow \({\dot{Q}}_\mathrm{v}\equiv A {\mathbf {v}}\) (with \(A=ab\) the transversal area of the channel) crossing the system from \(i=-N\) to \(i=N\). In continuous terms, Eq. (5) can be written

where we have assumed that \({\mathbf {v}}=(v,0,0)\) and \({\mathbf {q}}=-K_{\mathrm{{eff}}} \partial T/\partial x\) with \(K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}\) given by (10)–(14) and \(\sigma ^{\epsilon }=\dot{Q_i}'\).

Taking into account that \(\displaystyle \frac{\partial h}{\partial T}=C_\mathrm{p}\), with \(C_\mathrm{p}\) the specific heat at constant pressure, the general steady-state solution of (15) is

In our discretized version, \(\Delta T_i\) through the i-th column of cylinders is

where \(\displaystyle (i-1)\Delta x\) is the distance of the i-th column from the first column and \(\Delta x\) the gap between two consecutive columns. If we divide \(\Delta T_i\) by \(\Delta x\) and pass to the continuum, we get

where we have assumed that He II meets the first array of cylinders at \(x=-N\) with own temperature \(T_0\) (note that x gives the position in terms of \(\Delta x\) taken as reference length).

Solutions (16)–(18) obtain the combination of two different effects: (a) Forced convection brings heat in the positive x direction, whereas (b) heat conduction brings heat toward both positive and negative x directions [10] (refer to Fig. 1). The following two particular cases arise:

-

1.

In the absence of convection (\(v=0\)), from (15) we recover the parabolic profile for T found in [10], where heat is carried out toward sides.

-

2.

The linear solution \(T(x)=T_0+\frac{{\dot{Q}}'}{\rho C_\mathrm{p} v} (x+N)\) is obtained when the convective term balances the dissipated heat \({\dot{Q}}'\), namely when the balance Eq. (15) reduces to: \(\rho v C_\mathrm{p} \partial T/\partial x={\dot{Q}}'\). For other values of temperature, the exponential form in (18) is required.

The maximum possible value of \(T_{N}\) is restricted by the condition that \(T_{N}<T_{\lambda }\) in order to avoid transition to normal He I [22]. A second restriction is that the quantum Reynolds number \({{Re}}_\mathrm{q}\), defined by

has to be smaller than the temperature-dependent critical value \({{Re}}_{\mathrm{q,crit}}(T)\) for each cylinder column i, i.e., \({{Re}}_q(T_i) < {{Re}}_{\mathrm{q,crit}}(T)\), in order to avoid quantum turbulence [10, 18, 20]. Indeed, the critical value of \({{Re}}_q\) plays a decisive role in the appearance of quantum turbulence [13, 18].

A more complex scenario would consider this laminar flow condition not to hold for all the columns i, i.e., in some regions of the channel a transition to turbulent flow could occur, with the consequent nucleation of quantum vortices which could then be taken away by the convective flow.

5 Conclusions

With the analysis of this particular system, we want to cross the gap between the theoretical description of He II in the one-fluid extended model characterized by Eqs. (1)–(4), and the potential practical applications of it. In our case, the crucial element in this connection has been the evaluation of \(K_{\mathrm{{eff}}}\). This is achieved by suitable integration of the evolution Eq. (4) for the heat flux in the geometry of the problem being considered. Note that we have considered a relatively simple geometry (a regular array of cylinders). More complicated geometries would require particular numerical solutions, not amenable to specific algebraic analysis.

The truly practical outcome would be an algorithm characterizing the temperature of He II at each position of interest (i, j), given the values of each \({\dot{Q}}_{ij}\). In fact, our ultimate aim would be to know the temperature \(T_{i,j}\), of each cylindrical nanodevice, which will be different from the temperature of He II around it because of the corresponding Kapitza thermal resistance between the cylinders and the fluid. This resistance could be further increased if around the cylinders there was a localized turbulent region due to a local \({{Re}}_q\) higher than the critical value. Furthermore, one could consider that each nanodevice (i, j) has a different value for the heat dissipation rate \({\dot{Q}}_{ij}\), and one could try finding the optimal flow conditions for several different dissipation distributions.

Consideration of these additional points would make the problem more interesting and demanding, but also longer and more specific than we can afford in this limited space. The relatively simplified study illustrated in the present work shows a preliminar but successful combination between the fundamental physics of the thermodynamic description of He II and the position of its practical application.

References

S.W. Van Sciver, Helium Cryogenics, 2nd edn. (Springer, Berlin, 2012)

J.I. Cirac, P. Zoller, Quantum computation with cold trapped ions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 74, 4091–4094 (1995)

D.P. Di Vincenzo, The physical implementation of quantum computation. Forstchritte der Physik 48, 771 (2000)

T.D. Ladd, F. Jelezko, R. Laflamme, Y. Nakamura, C. Monroe, J.L. O’Biren, Quantum computing. Nature 464, 45–53 (2010)

S.A. Lyon, Spin-based quantum computing using electrons on liquid helium. Phys. Rev. A 74, 052338 (2006)

M.I. Dykman, P.M. Platzman, Quantum computing with electrons floating on liquid helium. Science 284, 1967–1969 (1999)

L.V. Levitin, R.G. Bennett, A. Casey, B. Cowan, J. Saunders, D. Drung, T. Schurig, J.M. Parpia, B. Ilic, N. Zhelev, Study of superfluid He under nanoscale confinement. J. Low Temp. Phys. 175, 667–680 (2014)

F.R. Bradbury, M. Takita, T.M. Gurrieri, K.J. Wilkel, K. Eng, M.S. Carroll, S.A. Lyon, Efficient clocked electron transfer on superfluid helium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 266803 (2011)

G. Yang, A. Fragner, G. Koolstra, L. Ocola, D.A. Czaplewski, R.J. Schoelkopf, D.I. Schuster, Coupling an ensemble of electrons on superfluid helium to a superconducting circuit. Phys. Rev. X 6, 011031 (2016)

M. Sciacca, A. Sellitto, L. Galantucci, D. Jou, Refrigeration of an array of cylindrical nanosystems by superfluid helium counterflow. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 104, 584–594 (2017)

C.F. Barenghi, R.J. Donnelly, W.F. Vinen, Quantized Vortex Dynamics and Superfluid Turbulence (Springer, Berlin, 2001)

R.J. Donnelly, Quantized Vortices in Helium II (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1991)

S.K. Nemirovskii, Quantum turbulence: theoretical and numerical problems. Phys. Rep. 524, 85–202 (2013)

M. Tsubota, M. Kobayashi, H. Takeuchi, Quantum hydrodynamics. Phys. Rep. 522, 191–238 (2013)

D. Jou, G. Lebon, M. Mongiovì, Second sound, superfluid turbulence, and intermittent effects in liquid helium II. Phys. Rev. B 66, 224509 (2002)

D. Jou, M. Mongiovì, Description and evolution of anisotropy in superfluid vortex tangles with counterflow and rotation. Phys. Rev. B 74, 054509 (2006)

M.S. Mongioví, Extended irreversible thermodynamics of liquid helium II. Phys. Rev. B 48, 6276–6283 (1993)

M. Sciacca, D. Jou, M.S. Mongioví, Effective thermal conductivity of helium II: from Landau to Gorter–Mellink regimes. Z. Angew. Math. Phys. 66, 1835–1851 (2015)

L.D. Landau, E.M. Lifshitz, Fluid Mechanics Course of Theoretical Physics, vol. 6 (Pergamon, London, 1959)

M. Sciacca, L. Galantucci, Effective thermal conductivity of superfluid helium: laminar, turbulent and ballistic regimes. Commun. Appl. Ind. Math. 7, 111–129 (2016)

M. Sciacca, A. Sellitto, D. Jou, Transition to ballistic regime for heat transport in helium II. Phys. Lett. A 378, 2471–2477 (2014)

M.S. Mongiovì, L. Saluto, Effects of heat flux on \(\lambda \)-transition in liquid 4He. Meccanica 49, 2125–2137 (2014)

Acknowledgements

D.J. acknowledges the financial support of the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness under Grant TEC2015-67462-C2-2-R. L.G.’s work is supported by Fonds National de la Recherche, Luxembourg, Grant No. 7745104. M.S. and L.G. acknowledge the National Group of Mathematical Physics (GNFM–INDAM) of Italy.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Jou, D., Galantucci, L. & Sciacca, M. Refrigeration of an Array of Cylindrical Nanosystems by Flowing Superfluid Helium. J Low Temp Phys 187, 602–610 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10909-016-1708-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10909-016-1708-4