Abstract

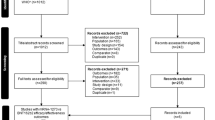

Language barriers (LB) contribute to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) health inequities. People with LB were more likely to be SARS-CoV-2 positive despite lower testing and had higher rates of hospitalization. Data on hospital outcomes among immigrants with LB, however, are limited. We aimed to investigate the clinical outcomes of hospitalized COVID-19 cases by LB, immigration status, ethnicity, and access to COVID-19 health information and services prior to admission. Adults with laboratory-confirmed community-acquired COVID-19 hospitalized from March 1 to June 30, 2020, at four tertiary-care hospitals in Montréal, Quebec, Canada were included. Demographics, comorbidities, immigration status, country of birth, ethnicity, presence of LB, and hospital outcomes (ICU admission and death) were obtained through a chart review. Additional socio-economic and access to care questions were obtained through a phone survey. A Fine-Gray competing risk subdistribution hazards model was used to estimate the risk of ICU admission and in-hospital death by immigrant status, region of birth and LB Among 1093 patients, 622 (56.9%) were immigrants and 101 (16.2%) of them had a LB. One third (36%) of immigrants with LB did not have access to an interpreter during hospitalization. Admission to ICU and in-hospital mortality were not significantly different between groups. Prior to admission, one third (14/41) of immigrants with LB had difficulties accessing COVID-19 information in their mother tongue and one third (9/27) of non-white immigrants with a LB had difficulties accessing COVID-19 services. Immigrants with LB were inequitably affected by the first wave of the pandemic in Quebec, Canada. In our study, a large proportion had difficulties accessing information and services related to COVID-19 prior to admission, which may have increased SARS-CoV-2 exposure and hospitalizations. After hospitalization, a large proportion did not have access to interpreters. Providing medical information and care in the language of preference of increasing diverse populations in Canada is important for promoting health equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to compromise of patients’ privacy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease 2019

- LB:

-

Language barriers

- MSDI:

-

Material and Social Deprivation Index

- NEWS2:

-

National Early Warning Score 2

References

Lopez L 3rd, Hart LH 3rd, and, Katz MH. Racial and ethnic health disparities related to COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(8):719–20.

Passos-Castilho AM et al. Outcomes of hospitalized COVID-19 patients in Canada: impact of ethnicity, migration status and country of birth. J Travel Med, 2022.

Quadri NS, et al. Evaluation of Preferred Language and timing of COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake and Disease outcomes. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(4):e237877–7.

Hayward SE, et al. Clinical outcomes and risk factors for COVID-19 among migrant populations in high-income countries: a systematic review. J Migr Health. 2021;3(100041):100041.

Guttmann A et al. COVID-19 in Immigrants, Refugees and Other Newcomers in Ontario: Characteristics of Those Tested and Those Confirmed Positive, as of June 13, 2020. 2020, ICES: Toronto, ON. p. 140.

Bowen S. Language barriers in access to health care. Health Canada: Ottawa; 2001.

Ortega P, Martínez G, Diamond L. Language and Health Equity during COVID-19: lessons and opportunities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2020;31(4):1530–5.

Ministère de l’Immigration et Communautés culturelles Québec. Présence en 2011 des immigrants admis Au Québec De 2000 à 2009, Direction De La Recherche et de l’analyse prospective Du ministère De l’Immigration et des Communautés culturelles, editor. Gouvernement du Québec: Quebec; 2011. pp. 1–3.

Espace Montréalais d’information sur la santé (EMIS). Portrait de santé des CIUSSS du Montreal, 2021. [Internet] 2021 2022 [cited 2021 December 30]; Available from: https://emis.santemontreal.qc.ca/sante-des-montrealais/portrait-global/portraits-de-sante-des-ciusss-de-montreal-2018/.

Statistics Canada. Census Profile, 2016 Census. 2021 [cited 2022 February 25]; Available from: https://www12.statcan.gc.ca/census-recensement/2016/dp-pd/prof/details/page.cfm?Lang=E&Geo1=CSD&Code1=2466023&Geo2=CD&Code2=2466&SearchText=montreal&SearchType=Begins&SearchPR=01&B1=Visible%20minority&TABID=1&type=1.

LeBlanc JJ, et al. Real-time PCR-based SARS-CoV-2 detection in Canadian laboratories. J Clin Virol. 2020;128:104433.

Statistics Canada. Visible minority of person. 2021 May 17, 2023]; Available from: https://www23.statcan.gc.ca/imdb/p3Var.pl?Function=DECI&Id=257515.

Charlson M, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Quan H, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–82.

Izzy S, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of latinx patients with COVID-19 in comparison with other ethnic and racial groups. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(10):ofaa401.

Chowdhury TA. Diabetes and COVID-19: Diseases of racial, social and glucose intolerance. World J Diabetes. 2021;12(3):198–205.

The Royal College of Physicians. National early warning score (NEWS) 2: standardising the assessment of acute-illness severity in the NHS. Updated report of a working party. London, UK: RCP; 2017. p. 77.

Institut national de santé publique du Québec (INSPQ). Index of material and social deprivation compiled by the Bureau d’information et d’études en santé des populations (BIESP) from 1991, 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016 Canadian Census data. 2019 [cited 2021 25 February]; Available from: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/en/deprivation/material-and-social-deprivation-index.

Bahar Özvarış Ş et al. COVID-19 barriers and response strategies for refugees and undocumented migrants in Turkey. J Migr Health, 2020. 1–2: p. 100012.

Brickhill-Atkinson M, Hauck FR. Impact of COVID-19 on resettled refugees. Prim Care. 2021;48(1):57–66.

Deal A, et al. Strategies and action points to ensure equitable uptake of COVID-19 vaccinations: a national qualitative interview study to explore the views of undocumented migrants, asylum seekers, and refugees. J Migr Health. 2021;4:100050.

Dhawan N, et al. Healthcare Disparities and the COVID-19 pandemic: analysis of primary Language and translations of Visitor policies at NCI-Designated Comprehensive Cancer centers. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2021;61(5):e13–6.

Flores G, et al. Errors of medical interpretation and their potential clinical consequences: a comparison of professional versus ad hoc versus no interpreters. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(5):545–53.

Lundon DJ, et al. Social determinants Predict outcomes in Data from a multi-ethnic cohort of 20,899 patients investigated for COVID-19. Front Public Health. 2020;8:571364.

Ingraham NE, et al. Racial and ethnic disparities in Hospital admissions from COVID-19: determining the impact of Neighborhood Deprivation and Primary Language. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(11):3462–70.

John-Baptiste A, et al. The effect of English language proficiency on length of stay and in-hospital mortality. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):221–8.

Karliner LS, et al. Do professional interpreters improve clinical care for patients with limited English proficiency? A systematic review of the literature. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(2):727–54.

Karliner LS, Perez-Stable EJ, Gregorich SE. Convenient Access to Professional interpreters in the Hospital decreases Readmission Rates and estimated hospital expenditures for patients with Limited English proficiency. Med Care. 2017;55(3):199–206.

Lindholm M, et al. Professional language interpretation and inpatient length of stay and readmission rates. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(10):1294–9.

Seale E, et al. Patient-physician language concordance and quality and safety outcomes among frail home care recipients admitted to hospital in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ. 2022;194(26):E899–e908.

Mazzalai E et al. Risk of Covid-19 severe outcomes and mortality in migrants and ethnic minorities compared to the General Population in the European WHO Region: a systematic review. J Int Migr Integr, 2023: p. 1–31.

Kebede LF. Language barrier adds to concern and confusion for Memphis parents over quarantine related to coronavirus, in Chalkbeat. Chalkbeat: Tennesse; 2020.

Cavallaro G, Contino G. Here’s how South Carolina is getting coronavirus information to spanish-speaking residents, Greenville News. 2020, Greenville News: Greenville, South Carolina.

Foy N. Many idahoans lack crucial coronavirus information. Who is trying to get the word out? In Idaho Statesman. Idaho Statesman: Boise, Idaho; 2020.

Kim HN, et al. Assessment of disparities in COVID-19 testing and Infection across Language Groups in Seattle, Washington. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):1–4.

Rozenfeld Y, et al. A model of disparities: risk factors associated with COVID-19 Infection. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(126):1–10.

Newbold B. The short-term health of Canada’s new immigrant arrivals: evidence from LSIC. Ethn Health. 2009;14(3):315–36.

Lu C, Ng E. Healthy immigrant effect by immigrant category in Canada. Health Rep. 2019;30(4):3–11.

Ng E, Pottie K, Spitzer D. Official language proficiency and self-reported health among immigrants to Canada. Health Rep. 2011;22(4):15–23.

Flores G. The impact of medical interpreter services on the quality of health care: a systematic review. Med Care Res Rev. 2005;62(3):255–99.

Jacobs EA, Sadowski LS, Rathouz PJ. The impact of an enhanced interpreter service intervention on hospital costs and patient satisfaction. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 2):306–11.

Jacobs EA, et al. Overcoming language barriers in health care: costs and benefits of interpreter services. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(5):866–9.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Azoulay holds a Chercheur-Boursier Senior Award from the Fonds de Recherche du Québec - Santé and is the recipient of a William Dawson Scholar award from McGill University. Dr. Passos-Castilho has received a postdoctoral fellowship from the Canadian Network on Hepatitis C (CanHepC). CanHepC is funded by a joint initiative of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (NPC-178912) and the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Funding

This work was supported by an Investigator Initiated Grant from Gilead and the Jewish General Hospital Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: Christina Greenaway.

Data curation: Olina Dagher.

Formal analysis: Ana Maria Passos-Castilho.

Funding acquisition: Christina Greenaway.

Methodology: Christina Greenaway, Cecile Rousseau, Andrea Benedetti, Laurent Azoulay.

Project administration: Christina Greenaway.

Resources: Christina Greenaway, Annie-Claude Labbé, Sapha Barkati, Me-Linh Luong.

Writing - original draft: Christina Greenaway, Ana Maria Passos-Castilho, Olina Dagher, Vasu Sareen.

Writing - review & editing: Ana Maria Passos-Castilho, Annie-Claude Labbé, Sapha Barkati, Me-Linh Luong, Olina Dagher, Vasu Sareen, Cecile Rousseau, Andrea Benedetti, Laurent Azoulay, Christina Greenaway.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This study was approved by the CIUSSS West-Central Montréal, the CIUSSS de l’Est-de-l’Île-de-Montréal, the McGill University Health Center, and the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal Review Ethics Boards.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Dr. Azoulay reports personal fees from Janssen and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. Dr. Greenaway has provided consultations for AbbVie and has received investigator-initiated grants from Gilead. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Dagher, O., Passos-Castilho, A.M., Sareen, V. et al. Impact of Language Barriers on Outcomes and Experience of COVID-19 Patients Hospitalized in Quebec, Canada, During the First Wave of the Pandemic. J Immigrant Minority Health 26, 3–14 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-023-01561-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-023-01561-7