Abstract

There has been limited longitudinal study of the health of migrant farmworkers due to their migratory lifestyles and there are opportunities to test new remote data collection methods in this subpopulation. A small randomized controlled trial was conducted with 75 migrant farmworker families who were randomly assigned to one of three groups that participated by (1) telephone interview, (2) online survey, or (3) mobile app between June 2021–April 2022. Of 50 farmworker adults who completed the baseline survey, there was differential attrition with 21% of the telephone interview group, 18% of the online survey group, and 3.2% of the online app group completing the 2-month follow-up. Over this period, migrant farmworkers reported relatively few mental health problems but notable alcohol use problems. Online apps were less effective than traditional methods for remote data collection. Alcohol use problems among migrant farmworkers in the U.S. may be an issue that deserves further study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mental health is a pressing issue among the estimated 2.5–3 million migrant farmworkers in rural America [1,2,3,4,5]. Studies have found that up to 45% of migrant farmworkers have reported moderate levels of depression [4, 6,7,8] and up to 18% have reported impairing levels of anxiety [4, 8, 9] compared to the general United States (U.S.) population with 4.2% experiencing moderate levels of depression and 2.7% experiencing severe anxiety [10]. However, there are various barriers for migrant farmworker families to access mental healthcare. These barriers might include costs of care, uninsurance, lack of transportation, language difficulties, cultural differences, limited knowledge about services, transient and migratory lifestyles, and stigma and fear of deportation and fear of law enforcement agencies [3, 4, 6, 7]. There has not been adequate longitudinal research on mental health, mental healthcare use, and related factors among migrant farmworkers to fully explore these issues.

One major challenge to conducting longitudinal research with migrant farmworkers is the migratory nature of their work and lifestyles as well as limited-English proficiency and limited access to technology and internet services in remote regions. There are various validated tools that have been developed to measure mental health of migrant farmworkers, such as the Spanish versions of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; [3]) and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; [4]). However, it is largely unknown to what extent administration of these measures and other data collection methods, such as online surveys and phone apps, are feasible and usable among migrant farmworker populations.

These issues became particularly salient during the Coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19 pandemic) which involved social distancing measures to be put in place and prohibited many in-person interactions like conducting in-person interviews, focus groups, and surveys. While there have been few cross-sectional reports indicating migrant farmworkers faced heightened vulnerabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic [11, 12], to date, there has been no published longitudinal study of the mental health of migrant farmworkers in the U.S. during the pandemic. Even beyond the pandemic, there is great utility in understanding the best methods to survey this important vulnerable working population.

In the current study, we conducted a small randomized controlled trial to test three different remote data collection methods with migrant farmworkers in South Texas with a 2-month follow-up period. The three remote methods were: telephone interview, online survey, or mobile app. To contribute to knowledge gaps on the mental health of U.S. migrant farmworkers during the COVID-19 pandemic, we also examined the mental health and well-being of the sample over time. The results will inform design and planning of future studies with this subpopulation as well as provide insights on the mental health of this subpopulation.

Methods

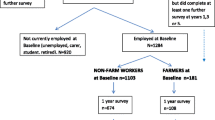

This study invited over 200 migrant farmworker family members residing in Texas and participating in the Education Service Centers (ESC) Migrant Education Program (MEP) between June 2021 and April 2022. The purpose of MEP is to “design and support programs that help migrant students overcome the challenges of mobility, cultural and language barriers, social isolation, and other difficulties associated with a migratory lifestyle” [13]. One feature of this program is the Parent Advisory Committee, which is comprised of migrant farmworker parents, schoolteachers, and other community partners, that meets throughout the academic year at ESC regions across Texas. Recruitment for this study occurred through the MEP and the Parent Advisory Committee. A total of 75 farmworker families agreed to participate and were randomly assigned to one of three groups to complete surveys by: (1) telephone survey; (2) online survey through Qualtrics, or (3) mobile app called LifeData. Participants were provided $10 compensation per assessment.

Research personnel randomized assignments by family unit; therefore, there were a different number of individuals assigned to each group. Out of a total of 150 individuals who were assigned, there were 109 adults and 41 adolescents. This study only included the adult participants. Of the 109 adults that were assigned to groups, there were 39 adults in the telephone group, 39 adults in the online survey group, and 31 adults in the mobile app group. To maximize data collection, research personnel invited participants who dropped out of their assigned group to continue the study by switching to a different data collection group of their preference. We conducted separate analyses on participants across groups after they had switched. No phone carrier charges for data or study application use were incurred by participants. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston (HSC-SPH-20-0756).

Measures

Across all groups, data were collected through a battery of self-report measures. These measures were made available in both English and Spanish depending on participant choice.

Sociodemographic and background characteristics were collected at baseline through a questionnaire that asked about age, gender, nationality, education, income, marital status, children, current housing situation and housing history, and employment.

Psychological stress was assessed with the Migrant Farm Worker Stress Inventory (MFWSI; [4]), a 39-item self-report, validated instrument that assesses the quality and severity of stress in migrant farm work. Participants are asked to rate how stressful they find statements on a five-point Likert scale from 0 (Have not experienced) to 4 (Extremely stressful). Responses are summed for a total score ranging from 0 to 156, with a threshold score of 80 or higher indicating relatively high levels of migrant farmworker stress (i.e., representing upper 25% of scores) [4].

Symptoms of major depressive and generalized anxiety disorders were assessed with the two-item Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-2; [14]) and the two-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2; [15]), which are each highly correlated with the longer versions of each respective measure (PHQ-9 and GAD-7). Both measures have been utilized in previous studies of Spanish-speaking populations [16]. Items on both the PHQ-2 and GAD-2 were summed with scores of ≥ 3 indicative of a positive screen for each respective disorder [17].

Symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) were assessed with the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist, Version 5 (PCL-5; [18]), which asked participants to refer to a “very stressful experience” in their life and to rate 20 symptoms of PTSD on the degree to which they experienced each symptom in the past year on a five-point Likert scale from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely. The PCL-5 has been well validated and tested on English and Spanish-speaking populations [19]. Responses were summed for a total score that ranged from 0 to 80 considered as ≥ 33 to be indicative of a positive screen for PTSD [20].

Symptoms of alcohol use disorder were assessed with the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) with a score ≥ 4 indicative of a positive screen [21].

Somatic symptoms were assessed with the Somatic Symptoms Scale-8 (SSS-8; [22]) which consisted of eight items that asked participants to rate how much they were bothered by common somatic symptoms within the past 7 days on a five-point Likert scale from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Very much). Responses were summed for a total score that ranged from 0 to 32.

Social support was assessed with the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS; [23]) which is a 12-item measure of perceived adequate of social support from three sources: family, friends, and significant others. Participants were asked to rate items on a seven-point Likert scale from 1 (Very strongly disagree) to 7 (Very strongly agree). Responses were summed for a total score that ranged from 12 to 84.

Data analysis

First, descriptive statistics were conducted to characterize the total sample and then the three groups at baseline. Bivariate analyses using t-tests and chi-square tests compared characteristics of the three groups at baseline. Second, frequency analyses were conducted to examine the level of study participation among the three groups over time. All these analyses were based on participants in their original group assignment. Third, repeated measures analysis of variance (rANOVA) for continuous variables and Cochrane’s Q test for categorical variables were conducted to examine changes in psychological stress, mental health, substance use, social support, and quality of life of the total sample longitudinally. This last set of analyses were based on the total sample irrespective of group and included participants who switched groups. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 17.0.

Results

As shown in Table 1, the majority of migrant farmworkers were aged 30 s (age range = 18–59), female, reported family annual income below $30,000, had lived in the U.S. an average of 18 years (range = 1–42 years), and lived with family with an average of five other household members (range = 2–7). In addition, 17% of participants reported they had experienced homelessness in adulthood with a total average of 195.8 days homeless in their lifetime (range 2–720). In terms of employment, participants reported they had worked an average of 13 years in agriculture (range = 1–45 years) and most worked in some type of produce harvesting as a migrant farmworker. Some participants held other jobs in addition to being migrant farmworkers, with the most common being jobs in the service industry.

In comparing the telephone, online survey, and online app groups, participants in the telephone group were significantly more likely to be from the U.S., had higher levels of education, and had fewer children compared to the other two groups. There were no other significant group differences on sociodemographic or background characteristics.

Table 2 shows the level of completion among the three groups over the 2 months of the study. Across groups, 50 migrant farmworker adults completed the baseline survey. There was differential attrition between groups starting at baseline, with 22 participants completing baseline in the telephone group (56.4% completion from initial assignment), 22 in the online survey group (56.4%), and 6 in the online app group (19.4% completion or 80.6% dropout). At 1 month, there was substantial attrition across groups as 30.8% of participants in the telephone group from initial assignment were retained, 25.6% retained in the online survey group, and 12.9% retained in the online app group. Finally, at 2 months, 66.6% of participants in the telephone group were retained from 1 month (or 20.5% retained since initial assignment), 70.0% retained in the online survey group (or 17.9% retained since initial assignment), and 25.0% retained in the online app group (or 3.2% retained since initial assignment).

Among those who dropped out, eight participants in the mobile app group dropped out and indicated their preference to be moved to the online survey group at baseline or 1 month; and one participant in the mobile app group dropped out and was moved to the telephone interview group. Across groups and after switches, a total of 50 participants completed the survey at baseline, 26 participants at 1-month follow-up, and 16 participants at 2-month follow-up.

Table 3 describes the mental health of participants across the three groups over the 2-month study period. Overall, the total sample reported relatively lower migrant farmworker stress; few symptoms of depression, anxiety, PTSD, and psychosomatic symptoms; and moderate levels of social support. Over 2 months, there was a significant increase observed in migrant farmworker stress and alcohol use problems, but declining anxiety and PTSD symptoms.

Discussion

This study contributes to research about the mental health of migrant farmworkers and strategies to overcome data collection challenges due to their migratory lifestyles and reservations about sharing personal health information. Through a small randomized trial, we tested three different remote data collection methods with a sample of U.S. migrant farmworkers and found that mobile phone apps like LifeData were not as effective in engaging migrant farmworkers as a survey method than traditional methods such as through phone interviews or online surveys. Only a handful of participants in the mobile app group completed the baseline assessment, so it is not that many were willing to use it and attrition occurred over time. Rather, it seems at least in our sample, most migrant farmworkers were reluctant to even start using the mobile app despite research personnel offering technical assistance on how to use the mobile app. It is not clear whether U.S. migrant farmworkers tend not to use mobile apps in general, or specifically mobile apps for health surveys. Regardless, our findings suggest mobile apps may not be the best remote data collection method for migrant farmworkers.

There are known barriers that may explain this, such as cultural differences, privacy concerns, fear of deportation and law enforcement, and lack of access to technologies and internet services in remote locations [3, 4, 6, 7]. Instead, we found that the highest rate of study participation was among migrant farmworkers who were engaged through traditional telephone interviews. Study participation by online survey was not far beyond telephone interviews (4% lower participation rate). These findings inform design and planning of future studies with U.S. migrant farmworkers on which remote data collection methods may be most fruitful, sample sizes needed, and the level of attrition that may be expected with each method.

Our sample of migrant farmworkers reported relatively low levels of farmworker stress (i.e., average score 35–39 out of 156) and did not report particularly high symptoms of depression, anxiety, or PTSD that warrant clinical attention during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, 8% of our sample screened positive for major depression and 6% screened positive for PTSD at baseline, which is comparable or lower than the estimated point prevalence of major depression and PTSD in the U.S. adult population [24, 25]. Moreover, migrant farmworker stress increased slightly over the 2-month study period, symptoms of depression, anxiety, and PTSD declined over time. Since we used a convenience sample, it is not clear how generalizability our findings are. However, our findings suggest U.S. migrant farmworkers have been quite resilient in their mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, which accord with recent studies that have found veterans with severe mental illness or recent homelessness have fared better in their mental health than those in the general population [26, 27]. Migrant farmworkers, along with other subpopulations, who have experienced considerable adversities in their lives may have developed a certain level of resilience that mitigated and protected psychological impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

One area that may deserve clinical attention is the level of alcohol use reported in our sample. In our small sample size, we observed increases in reported alcohol use problems over time with about 19% of migrant farmworkers screening positive for alcohol use problems which is higher than the 10–13% prevalence of high-risk drinking found in the general U.S. adult population [28]. Several studies over the past decade have reported high alcohol consumption among farmworkers in general, and the negative health and social consequences of their heavy drinking [29, 30]. Increased problems with alcohol use have been consistently reported in the general U.S. population during the COVID-pandemic [31,32,33] and further study is needed to determine whether this was this “COVID-19 effect” on alcohol consumption disproportionately impacted migrant farmworkers. This is an area that needs follow-up evaluation to observe whether alcohol use problems remain elevated in the population or return to baseline levels in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

There were several limitations of this study worth noting. We had a small sample size so our findings should be interpreted with caution and study replication with a larger sample size is needed. We followed migrant farmworkers for a duration of 2 months; a longer follow-up period may yield further insights about our different data collection methods and richer data about their mental health. Our data was based on self-report and subject to recall and respondent bias, especially since there is social stigma around mental health status that may have affected the openness of migrant farmworkers from sharing information about their mental health. We did not assess level of acculturation/assimilation which are important constructs related to psychosocial functioning [34,35,36]. The COVID-19 pandemic was a complex event that involved not only disease transmission but social distancing measures, city lockdowns, restrictions on international travel, and social strife—all of which may have impacted the results in unmeasured ways. Last, we focused on migrant farmworkers in the U.S. who lived in Texas who were predominantly Mexican–American adults and it is unknown whether these findings would be generalizable to other Hispanic subgroups or migrant farmworkers outside the U.S.

New Contribution to the Literature

Limitations notwithstanding, this study contributes to knowledge about effective remote data collection methods to assess the mental health of U.S. migrant farmworkers. This study provides needed information to guide future design of migrant farmworker studies by finding phone interviews and online surveys are much more effective in engaging and obtaining data from migrant farmworkers than mobile apps over multiple follow-up periods. Mobile apps may not be as readily adopted by migrant farmworkers, migrant farmworkers may be reluctant to share personal information on mobile apps, and mobile apps may not yield completion rates as high as traditional data collection methods. More work is needed to encourage adoption of mobile apps or develop ways to maximize traditional data collection methods to conduct beneficial research for the migrant farmworker population. Remote data collection methods were useful and necessary during the COVID-19 pandemic, which revealed migrant farmworkers in our study were resilient in their mental health over time during the pandemic. Further study is needed to understand the psychosocial and cultural factors underlying the resilience of migrant farmworkers and under what circumstances are remote data collection methods best to use for this population.

References

Arcury TA, Quandt SA. Delivery of health services to migrant and seasonal farmworkers. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:345–63.

Hansen E, Donohoe M. Health issues of migrant and seasonal farmworkers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2003;14(2):153–64.

Anthony MJ, Martin EG, Avery AM, Williams JM. Self care and health-seeking behavior of migrant farmworkers. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(5):634–9.

Hiott AE, Grzywacz JG, Davis SW, Quandt SA, Arcury TA. Migrant farmworker stress: mental health implications. J Rural Health. 2008;24(1):32–9.

National Center for Farmworker Health. Facts about Agricultural Workers: National Center for Farmworker Health, 2020.

Ramos AK, Su D, Lander L, Rivera R. Stress factors contributing to depression among Latino migrant farmworkers in Nebraska. J Immigr Minor Health. 2015;17(6):1627–34.

Donlan W, Lee J. Screening for depression among indigenous Mexican migrant farmworkers using the patient health questionnaire–9. Psychol Rep. 2010;106(2):419–32.

Mora DC, Quandt SA, Chen H, Arcury TA. Associations of poor housing with mental health among North Carolina Latino migrant farmworkers. J Agromedicine. 2016;21(4):327–34.

Crain R, Grzywacz JG, Schwantes M, Isom S, Quandt SA, Arcury TA. Correlates of mental health among Latino farmworkers in North Carolina. J Rural Health. 2012;28(3):277–85.

Zablotsky B, Weeks JD, Terlizzi EP, Madans JH, Blumberg SJ. Assessing anxiety and depression: A comparison of National Health Interview Survey measures. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2022 Contract No.: 172.

Haley E, Caxaj S, George G, Hennebry J, Martell E, McLaughlin J. Migrant farmworkers face heightened vulnerabilities during COVID-19. J Agric Food Syst Community Dev. 2020;9(3):35–9.

Vosko LF, Basok T, Spring C, Candiz G, George G. Understanding migrant farmworkers’ health and well-being during the global COVID-19 pandemic in Canada: toward a transnational conceptualization of employment strain. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(14):8574.

ESC-20. Welcome to the Migrant Education Program. ESC-20. n.d. https://www.esc20.net/apps/pages/migrant-education. Accessed Jan 5, 2023.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The patient health questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depression screener. Med Care. 2003;41(11):1284–92.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Monahan PO, Löwe B. Anxiety disorders in primary care: prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(5):317–25.

Reyes S, Acosta LM, Domínguez V, Ramos AK, Andrews AR III. Immigrant and US-born migrant farmworkers: dual paths to discrimination-related health outcomes. Am J Orthopsych. 2022;92(4):452–62.

Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606–13.

Weathers FW, Litz BT, Keane TM, Palmieri PA, Marx BP, Schnurr PP. The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, National Center for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, Washington, DC. 2013. http://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/assessment/adult-sr/ptsd-checklist.asp. Accessed April 8, 2014.

Marshall GN. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom checklist: factor structure and English-Spanish measurement invariance. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17(3):223–30.

Bovin MJ, Marx BP, Weathers FW, Gallagher MW, Rodriguez P, Schnurr PP, et al. Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist for diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders-fifth edition (PCL-5) in veterans. Psychol Assess. 2016;28(11):1379–91.

Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonnell MB. The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. JAMA Intern Med. 1998;158(16):1789–95.

Gierk B, Kohlmann S, Kroenke K, Spangenberg L, Zenger M, Brähler E, et al. The somatic symptom scale–8 (SSS-8): a brief measure of somatic symptom burden. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(3):399–407.

Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52:30–41.

Brody DJ, Pratt LA, Hughes JP. Prevalence of depression among adults aged 20 and over: United States, 2013–2016. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2018 Contract No.: 303.

Schein J, Houle C, Urganus A, Cloutier M, Patterson-Lomba O, Wang Y, et al. Prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder in the United States: a systematic literature review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37(12):2151–61.

Wynn JK, McCleery A, Novacek DM, Reavis EA, Senturk D, Sugar CA, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and functional outcomes in Veterans with psychosis or recent homelessness: a 15-month longitudinal study. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(8):e0273579.

Pietrzak RH, Tsai J, Southwick SM. Association of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder with posttraumatic psychological growth among US veterans during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(4):e214972.

Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Kerridge BT, Ruan WJ, et al. Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001–2002 to 2012–2013: results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. JAMA Psychiat. 2017;74(9):911–23.

Worby PA, Organista KC. Alcohol use and problem drinking among male Mexican and Central American im/migrant laborers: a review of the literature. Hisp J Behav Sci. 2007;29(4):413–55.

Arcury TA, Talton JW, Summers P, Chen H, Laurienti PJ, Quandt SA. Alcohol consumption and risk for dependence among male Latino migrant farmworkers compared to Latino nonfarmworkers in North Carolina. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2016;40(2):377–84.

Pollard MS, Tucker JS, Green HD. Changes in adult alcohol use and consequences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(9):e2022942.

Kim JU, Majid A, Judge R, Crook P, Nathwani R, Selvapatt N, et al. Effect of COVID-19 lockdown on alcohol consumption in patients with pre-existing alcohol use disorder. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5(10):886–7.

Barbosa C, Cowell AJ, Dowd WN. Alcohol consumption in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. J Addict Med. 2021;15(4):341–4.

Tsai J, Gu X. Homelessness among immigrants in the United States: rates, correlates, and differences compared with native-born adults. Public Health. 2019;168:107–16.

Lara M, Gamboa C, Kahramanian MI, Morales LS, Hayes Bautista DE. Acculturation and Latino health in the United States: a review of the literature and its sociopolitical context. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:367–97.

Choy B, Arunachalam K, Gupta S, Taylor M, Lee A. Systematic review: acculturation strategies and their impact on the mental health of migrant populations. Public Health in Practice. 2021;2:100069.

Funding

There was no specific funding for this project and this work was supported by internal university funds.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

None of the authors report any conflicts of interest with this work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Tsai, J., Rodriguez, A. & Solis, V. A Small Randomized Controlled Trial of Three Remote Methods to Collect Mental Health Data from Migrant Farmworker Adults. J Immigrant Minority Health 25, 1025–1032 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-023-01452-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-023-01452-x