Abstract

Cultural background influences how migrants and ethnic minority populations view and assess health. Poor oral health literacy (OHL) may be a hindrance in achieving good oral health. This systematic review summarizes the current quantitative evidence regarding OHL of migrants and ethnic minority populations. The PubMed database was searched for original quantitative studies that explore OHL as a holistic multidimensional construct or at least one of its subdimensions in migrants and ethnic minority populations. 34 publications were selected. Only 2 studies specifically addressed OHL in migrant populations. Generally, participants without migration background had higher OHL than migrant and ethnic minority populations. The latter showed lower dental service utilization, negative oral health beliefs, negative oral health behavior, and low levels of oral health knowledge. Due to its potential influence on OHL, oral health promoting behavior, attitudes, capabilities, and beliefs as well as the cultural and ethnic background of persons should be considered in medical education and oral health prevention programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Due to the important interrelationship between oral and general health, oral health has been set as a Leading Health Indicator 2020 [1]. Oral inflammation (e.g. periodontitis) has been linked to non-communicable diseases such as cardiovascular diseases and diabetes [2,3,4], which both have a large impact on the health care economy [5]. The treatment of oral diseases can pose a great financial burden: not only at the individual level, but also for health care systems, as they are widespread and recurring [5]. In the European Union (EU) 79 billion EUR p. a. was spent on dental care between 2008 and 2012, which is expected to rise to 93 billion EUR in 2020 [5, 6]. Additionally, poor oral health has been shown to have a negative effect on quality of life [7,8,9,10,11].

Among other risk factors, having a migration background appears to be a risk factor for poor oral health [12,13,14,15]. Limited oral health literacy (OHL) is probably one reason for poor oral health in these populations. Current definitions of OHL have been based on the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of health literacy: “the cognitive and social skills which determine the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health." [16]. Migrant populations usually represent a very heterogeneous group of persons with varying oral health knowledge, diverse beliefs and attitudes, shaped by their culture and past experiences with the respective health care system in their home countries. Therefore, these migrant populations may not fit well in the “health care culture” of their host country and subsequently do not sufficiently benefit from it. In fact, previous research has found that being a migrant had a profound effect on ones’ awareness of disease and health management. This awareness usually differs from the common health perceptions in the host country [17].

Various studies dealing with migrant or ethnic minority groups have reported beliefs and attitudes about oral health that may fundamentally shape the way they view and manage their oral health. For example, beliefs such as that retaining ones’ natural teeth during old age will bring misfortune to the family [18, 19] and that caries and tooth loss is part of a natural aging process [18] have been reported in Chinese immigrants in various host countries (e.g. Canada, England). A study investigating the oral health beliefs of Mexican-Americans regarding nutrition found that many staple foods with high amounts of sugar were not perceived to be rich in sugar (e.g. high carbohydrate foods, ketchup, sweet rolls) [20]. Thus, misconceptions and a resulting unhealthy diet may prevent persons from maintaining good oral health. Such differences in attitudes and beliefs may be a hindrance to interaction with the host country’s health care system and participation in health care interventions.

The influence of culture on OHL, as well as important components of OHL, can be explained by using the conceptual framework by Hongal et al. [21]. According to this framework, the management of one’s oral health, the patient-doctor interaction, oral health behaviors and attitudes, and the educational and health care system with which a person interacts – all affect one’s OHL. Furthermore, these factors additionally interact with one’s oral health knowledge, literacy, interests in oral health, and the ability to access oral health information and services. The societal, family, and peer influences within the different societies and cultures of migrants and ethnic minorities may positively or negatively affect their literacy skills in the language of the host country, thereby influencing their oral health knowledge, their ability to access oral health information and services, their oral health-related attitudes, and, subsequently, their OHL.

However, to date, only single studies have investigated OHL in migrant or ethnic minority populations and no review of this possible relationship and the specific determinants has been published. Therefore, this paper aims to systematically review and summarize research findings about OHL of adult migrant and ethnic minority populations in quantitative studies. The focus lays on adults, because previous research suggests that the OHL of caregivers (e.g. parents) plays an important role in ensuring good oral health in children [22,23,24]. Through targeted education of the parents, the oral health outcomes in children should be improved as well [24].

Methods

The study was reviewed and approved by the ethics review committee at the Medical University Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (LPEK-0027). As the study does not involve human participants, human data, or human tissue, there were no ethical concerns.

The SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research) method [25] was applied to generate the search strategy. The following terms related to the concept “migrant” were included (S): migrant*, migrat*, immigrant*, immigrat*, emigrat*, refugee*, ethnic*, and race. To assess the concept “oral health literacy” (PI), the terms “oral, dental, literacy, knowledge, coping, self-management, health promotion, and health prevention” were used (Table 1).

Because of the lack of research on this topic and the possibility of unintentionally excluding relevant studies, no restrictions were applied to the search strategy in terms of the evaluation (E) of the publications. Original quantitative publications were included (D, R). No time restriction was applied as an exclusion criterion. Only publications in German or English were included. During the initial title screening, all publications unrelated to oral health were removed. During abstract and full text screening, studies were excluded, which had no focus on migration/ethnicity/race, included persons under 18 years old, included data other than original quantitative data, did not deal with OHL or at least one of its indicators (e.g. oral health knowledge, dental service utilization, oral health beliefs), or focused only on clinical health status instead of OHL. A criteria list for the abstract and full text screening was developed and used by the two reviewers for the screening of abstracts and full texts. Any discrepancies found during the selection of the full texts to be included in the review were discussed and resolved.

Results

A total of 201 publications was selected for abstract screening, resulting in 58 publications for the full text screening. Of these 58 publications, 5 full texts could not be found despite contacting the authors, and 19 were excluded from the review based on the criteria listed in Fig. 1. This review includes a total of 34 publications, originating from industrialized countries like Australia, Austria, Canada, China, Israel, Germany, Norway, Sweden, and the United States (US), with the majority coming from the US (N = 24).

OHL Studies in Migrants and Racial/Ethnic Groups

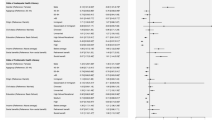

Only 8 studies specifically explored OHL, originating from the US (N = 7) and Canada (N = 1). Of these 8 studies, only 2 studies specifically targeted migrant populations [26, 27], while all others collected data about ethnicity or race [28,29,30,31,32,33]. Measurement of OHL or HL in dentistry in these studies consisted mainly of word recognition tests (e.g. REALM-D [34] for dental-related terms or S-TOFHLA, a generic test of functional literacy in adults [35]).

Geltman and colleagues [27] used the REALD-30 as a measure for HL in dentistry as well as the S-TOFHLA in a sample of Somali refugees, where 73% had low REALD-30 scores and 74% had low S-TOFHLA scores (Table 2). People with higher REALD-30 scores and higher English proficiency were twice as likely to visit the dentist for preventive purposes within the preceding year. However, these associations disappeared when controlling for the effects of acculturation and stratifying by sojourn time in the US.

Calvasina [26] reported that 83.1% of Brazilian immigrants living in Canada who participated in their study had adequate OHL as measured by the OHLI developed by Sabbahi et al. [36], which contains numeracy and reading comprehension items. However, 46.5% of the participants had inadequate oral health knowledge. Limited OHL was associated with not visiting a dentist in the preceding year, not having a dentist as a primary information source, and not participating in shared dental treatment decision making. English comprehension in this sample is implied to be low. The majority (86.1%) of participants in this study chose to complete the questionnaire in Portuguese (Tables 3 and 4).

OHL-studies collecting only race/ethnicity data found that high education and English competency were associated with higher scores in REALM-D [28, 32] and REALD-30 [30] in non-Caucasian participants than in Caucasian participants. For instance, one study observed significantly higher REALM-D scores in non-Hispanic Caucasians than Hispanics [32]. The study by Tam et al. [33] also observed significant associations between OHL (REALMD-20 & REALMD) and race/ethnicity as well as OHL and education. Another study using the S-TOFHLA within a dental research context [31] observed that Caucasian females had higher HL scores than African American males. Moreover, higher age was also associated with lower HL. Messadi et al. [32] also collected ethnicity/race data and observed high S-TOFHLA (S-TOFHLA score > 22) mean scores in all ethnic groups. However, the scores were highest in non-Hispanic Asians, followed by non-Hispanic Caucasians, African Americans, and Hispanics. In a sample of ethnically diverse female caregivers, no significant associations between OHL (REALD-30) and dental service utilization were detected [29].

Studies Investigating Dental Service Utilization, Oral Health Behavior, Oral Health Beliefs, and Oral Health Knowledge in Migrants

The majority of studies investigating at least one component of OHL in migrant populations collected data on dental service utilization [14, 37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. Six of these studies took place in the US; they show different results in various migrant populations. A study by Xhihani et al. [46] that explored the dental service utilization of Albanian immigrants (mean duration of stay in US = 12.9 years) observed high utilization of dental services, with 68% of this group having visited the dentist within the past year. Wu et al. [47] investigated the dental service utilization patterns of older Chinese and Russian immigrants (60 + years old) in the US and found that both had a low service utilization rate. Among them, fewer Chinese elders (46.9%) had used dental services in the last 12 months than Russian elders (60.3%). Predictors were different in these groups. Education, length of stay in the US, social support, and smoking behavior were significant indicators for the use of dental services among older Chinese, while age, income, and denture use were significant indicators for dental service utilization in older Russian immigrants.

Another study in 2010 examining the determinants of oral health care utilization among a diverse group of immigrants in New York City observed that the majority of Asian, Hispanic, and African American Caribbean immigrants reported not having a regular source of dental care, not having dental insurance, and not having visited the dentist within the last 12 months (> 70% in all groups) [37]. A positive association between having a regular source of dental care and dental service utilization was observed in all ethnic groups.

Other US-studies focused on various refugee populations. In 2007, Okunseri and colleagues reported that 39% of Hmong refugees did not have a regular source of dental care and only 43% had visited the dentist within the last 12 months [42]. A study involving refugees from Sudan [45] reported that 56% of participants had used dental services only once since arriving in the US (the duration in the US ranged between 10–13 years). None of them reported going to the dentist for a biannual checkup [45].

Further studies outside of the US were focusing on: Chinese immigrants in Canada [39], Indonesian workers in Hong Kong [48], Greek and Italian immigrants in Australia [40], Pakistani immigrants in Norway [14], Finish immigrants in Sweden [44], refugees from Syria, Iraq, and Afghanistan in Austria [38]. All these studies revealed a low dental service utilization among migrants. However, the predictors for dental service utilization varied between these migrant populations. Level of education [39], number or condition of remaining teeth [14, 40], duration of stay in the host country [14], fluency in the host country’s language [38,39,40, 44, 48], costs of dental services [14, 40], familiarity with the host country’s dental health care system [44], and possibilities in getting a dental appointment [14, 40, 44] were reported as factors for (non-)utilization of dental services.

A few studies also observed oral health beliefs. In a study in Hong Kong, Indonesian workers reported to believe in the importance of regular dental check-ups [48], while the older Albanian immigrants in a study of Xhihani and colleagues [46] in the US did not believe retaining one’s teeth to be important and considered bleeding gums as normal. In Germany, the majority of Syrian and Iraqi refugees believed that oral diseases can affect general health and, thus, tooth brushing improves health [49].

Several studies collecting data on oral health behavior in migrants reported that flossing the teeth is rare to non-existent [37, 48], while regular tooth brushing (twice a day) seems to be quite common [42, 48, 49]. Nevertheless, despite brushing the majority of participants in the two studies that assessed oral hygiene had plaque/calculus [48, 49]. Due to the findings of Gao et al. as well as of Vered et al. the oral health behavior of immigrants can improve, such as more frequently flossing [48] or switching from traditional means of oral hygiene (e.g. chewing sticks) to toothbrushes [43].

Two studies measuring oral health knowledge found low scores in Greek and Italian migrants [40], while in another study in Norway more than half of a population of Pakistani immigrants were knowledgeable of questions about etiology of dental diseases [14].

Studies Investigating Dental Service Utilization, Oral Health Behavior, Oral Health Beliefs, and Oral Health Knowledge in Racial/Ethnic Minority Groups

Studies investigating the dental service utilization in minority racial/ethnic groups in the US and in Canada (e.g. Hispanics, African Americans, Native Americans, Chinese-Americans) reported that these populations were less likely than Caucasians to obtain dental care [50,51,52,53,54]. Davidson et al. [51] reported different predictors of dental service utilization, such as fear, pain, and education, between ethnic groups.

Varying levels of oral health knowledge were observed in studies collecting data only about race/ethnicity. The ones performed in the US found that Caucasians typically had a better oral health knowledge than other racial/ethnic groups [52, 55,56,57,58]. On the other hand, high oral health knowledge was reported in samples of American Indians and Alaskan natives [59] as well as Korean-Americans [60].

Oral health beliefs also varied between different race/ethnic minority groups. Although most studies observed that ethnic/racial minority groups have negative oral health beliefs (e.g. not believing in the benefits of preventive dental care) [52, 55, 57, 61], one study observed positive oral health beliefs (e.g. believing that following recommended oral hygiene is important) in American Indians and Alaskan natives in the US [59].

Oral health behavior also differed between studies. Boggess and colleagues [50] reported that oral hygiene practices significantly varied among ethnicities and races of pregnant women. African American women were more likely than Caucasian and Hispanic women to brush their teeth only once a day or less; and Hispanic women were more likely to use dental floss than Caucasian and African American women. Kiyak et al. [57] reported that Caucasians had a higher risk not to practice positive oral health behaviors than Asians, and a Canadian study observed more often a negative oral health behavior (e.g. never flossing) in Italians compared to those identifying themselves as being Canadian, British, Jewish, or “Other” [53].

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first review that summarizes the research done about OHL and sub-dimensions of OHL (e.g. oral health knowledge, dental service utilization, oral health behaviors and beliefs) of migrants and ethnic/racial minority groups in various host countries. The results of this review show that cultural context and culturally determined beliefs influence the behavior of migrants and ethnic minorities in promoting and maintaining good oral health.

The two studies that aimed to measure OHL in immigrants focused on literacy (reading ability) and observed contrary OHL levels [26, 27]. The reason, probably, is that the sample in one study [26] completed the OHL-assessment in their native language, while the other did not [27]. Similar trends were seen in OHL studies with ethnic minority groups, in which non-Caucasian participants achieved lower literacy scores than their Caucasian counterparts, which was attributed to education and also their proficiency in the language of the host country [28, 30, 32, 33]. Although low education and socioeconomic status has been associated with low HL [62,63,64], the presently reviewed studies suggest that existing OHL instruments (especially those which only assess functional literacy) may lead to a skewed and incomplete estimation of OHL due to language barriers [65, 66]. Consequently, if the user is not fluent in the language of the host country, OHL-instruments should be provided in the user’s mother tongue. Otherwise, the results would indicate insufficient language skills rather than OHL.

Other important components of OHL, such as culturally influenced oral health attitudes and behaviors, may not be adequately assessed and considered when exploring the overall OHL of immigrant and minority populations. For example, 83.1% of the Brazilian immigrants in the study by Calvasina et al. [26] exhibited adequate numeracy and reading comprehension, but only 29.7% had adequate oral health knowledge. This further supports the idea that despite of adequate functional literacy (as an important component of OHL), there are other relevant factors that play a role in achieving a high OHL.

The results of the studies that explore oral health beliefs, behavior, and service utilization in immigrant and minority groups suggest that the individual cultural background has a significant influence on how migrants and minorities promote and maintain good oral health. In many instances, these cultural influences may attribute to a less than ideal management of oral health. Nonetheless, there have also been instances where populations have exhibited good oral health beliefs [48, 49, 59] and behavior [50, 57], suggesting that the heterogeneous cultural contexts of migrants and ethnic groups can specifically affect one’s health. In fact, research in different populations has observed that oral health beliefs were significantly related to adherence in oral hygiene instructions during periodontal treatment [67] and in preventive dental advice [68]. Health care utilization has also been noted to be lower in immigrants than in native populations, with health beliefs being noted as an understudied, but potentially significant influencing factor [69].

In light of these results, several fields of action arise to improve the OHL in immigrants and minority groups. (Of course, these may count for other health areas and issues as well.) For example, knowledge of risk and severity of oral diseases, benefits of good oral health rather than just avoiding bad oral health, perceived barriers, and measures for improving oral health could be disseminated in a trustful, culturally sensitive way. This may, in turn, increase interest and access to oral health information and services, promote positive oral health behavior and attitudes, support management of oral health, improve patient-doctor interactions, enhance self-efficacy, and thus increase overall OHL. On the health system’s/dental practitioner’s side, continuing training of intercultural competencies in the education of dental students, dentists, and other stakeholders in the provision of oral health care could be provided. In fact, previous research in dental public health has noted that understanding the culture of diverse populations being served is important for the quality of (oral) health care [70] and should be a natural part of the dental curricula [70, 71]. Conveying the importance of these competencies can enhance dental care providers’ interest and will to learn about the specific cultures of their patients. This would be an important basis to increase both the adherence in the dentist-patient-relationship and, as a consequence, the patients’ OHL.

One strength of this systematic review is the inclusion of studies that not only explore OHL explicitly, but also sub-dimensions of OHL that have not been indicated, key worded, or categorized as OHL. This has widened the understanding of OHL or components of OHL, respectively, in migrants and ethnic minority groups, where word recognition tests have been most widely used as a measure of OHL [72]. Another notable aspect of this reviewing process is that the exploration of the research field, the development and conceptualization of the research question, the definition of search terms, and the overall review process itself were conducted by an interdisciplinary team composed of dental practitioners and senior researchers, psychologists, health scientists, and sociologists. This widened the view and allowed for many different aspects and thoughts to be included in the development process.

It should be noted that this review has some potential limitations. Limiting the search to the PubMed database can be seen as one. Not using other databases or grey literature books was decided upon, because most health literacy research related to dentistry would be found in PubMed. We cannot exclude a publication bias that may have resulted from the known fact that significant results are more likely to be published than insignificant results [73]. Although this review is limited to scientific-medical sources, it does likely provide a comprehensive view of the current state of scientific knowledge about OHL.

Conclusions

Results of this review suggest that cultural context and ethnic affiliation significantly influence migrants’ and ethnic minorities’ behavior in promoting and maintaining good oral health. Although immigrant and minority groups generally showed lower OHL and OHL-related competencies than the native populations, some groups even showed better ones, which underlines the heterogeneity of these different groups, which thus should be handled uniquely. Additionally, our results may suggest that dentists and staff should be aware and open to the possibility that people with a different cultural background have different attitudes, capabilities, and belief systems concerning oral health. Considering these differences should be part of a culturally sensitive approach in medical education and future oral health programs.

References

HealthyPeople.gov. Oral Health, 2014. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/leading-health-indicators/2020-lhi-topics/Oral-Health. Accessed 1 Jul 2019

Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366(9499):1809–20.

Lockhart PB, et al. Periodontal disease and atherosclerotic vascular disease: does the evidence support an independent association? A scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;125(20):2520–44.

FDI World Dental Federation. FDI policy statement on oral infection/inflammation as a risk factor for systemic diseases. Adopted by the FDI General Assembly: 30 August 2013 – Istanbul, Turkey. Int Dent J. 2013;63(6):289–90.

Jin LJ, et al. Global burden of oral diseases: emerging concepts, management and interplay with systemic health. Oral Dis. 2016;22(7):609–19.

Patel, R., The State of Oral Health in Europe. 2012, Platform for Better Oral Health in Europe.

Ferreira MC, et al. Impact of periodontal disease on quality of life: a systematic review. J Periodontal Res. 2017;52(4):651–65.

Buset SL, et al. Are periodontal diseases really silent? A systematic review of their effect on quality of life. J Clin Periodontol. 2016;43(4):333–44.

Schierz O, et al. Comparison of perceived oral health in patients with temporomandibular disorders and dental anxiety using oral health-related quality of life profiles. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(6):857–66.

Reissmann DR, et al. Functional and psychosocial impact related to specific temporomandibular disorder diagnoses. J Dent. 2007;35(8):643–50.

Baba K, et al. The relationship between missing occlusal units and oral health-related quality of life in patients with shortened dental arches. Int J Prosthodont. 2008;21(1):72–4.

Batra M, Gupta S, Erbas B. Oral health beliefs, attitudes, and practices of South Asian migrants: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16:11.

Arora G, et al. Ethnic differences in oral health and use of dental services: cross-sectional study using the 2009 Adult Dental Health Survey. BMC Oral Health. 2016;17(1):1.

Selikowitz HS, Holst D. Dental health behavior in a migrant perspective: use of dental services of Pakistani immigrants in Norway. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1986;14(6):297–301.

Williams SA, et al. Caries experience, tooth loss and oral health-related behaviours among Bangladeshi women resident in West Yorkshire, UK. Commun Dent Health. 1996;13(3):150–6.

WHO. The WHO Health Promotion Glossary. Geneva: WHO; 1998.

Ackermann Rau S, Sakarya S, Abel T. When to see a doctor for common health problems: distribution patterns of functional health literacy across migrant populations in Switzerland. Int J Prosthodont. 2014;59(6):967–74.

Smith A, et al. The influence of culture on the oral health-related beliefs and behaviours of elderly Chinese immigrants: a meta-synthesis of the literature. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 2013;28(1):27–47.

Kwan SY, Holmes MA. An exploration of oral health beliefs and attitudes of Chinese in West Yorkshire: a qualitative investigation. Health Educ Res. 1999;14(4):453–60.

Maupome G, Aguirre-Zero O, Westerhold C. Qualitative description of dental hygiene practices within oral health and dental care perspectives of Mexican-American adults and teenagers. J Public Health Dent. 2015;75(2):93–100.

Hongal S, et al. Assessing the oral health literacy: a review. Int J Med Public Health. 2013;3:1.

Miller E, et al. Impact of caregiver literacy on children’s oral health outcomes. Pediatrics. 2010;126(1):107–14.

Bridges SM, et al. The relationship between caregiver functional oral health literacy and child oral health status. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;94(3):411–6.

Reza M, et al. Oral health status of immigrant and refugee children in North America: a scoping review. J Can Dent Assoc. 2016;82:3.

Cooke A, Smith D, Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–43.

Calvasina P, et al. Brazilian immigrants’ oral health literacy and participation in oral health care in Canada. BMC Oral Health. 2016;16:18.

Geltman PL, et al. Health literacy, acculturation, and the use of preventive oral health care by Somali refugees living in massachusetts. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(4):622–30.

Atchison KA, et al. Screening for oral health literacy in an urban dental clinic. J Public Health Dent. 2010;70(4):269–75.

Burgette JM, et al. Is dental utilization associated with oral health literacy? J Dent Res. 2016;95(2):160–6.

Divaris K, et al. The relationship of oral health literacy with oral health-related quality of life in a multi-racial sample of low-income female caregivers. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2011;9:108.

Jackson RD, Eckert GJ. Health literacy in an adult dental research population: a pilot study. J Public Health Dent. 2008;68(4):196–200.

Messadi DV, et al. Oral health literacy, preventive behavior measures, and chronic medical conditions. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2018;3(3):288–301.

Tam A, et al. The association of patients’ oral health literacy and dental school communication tools: a pilot study. J Dent Educ. 2015;79(5):530–8.

Davis TC, et al. Rapid assessment of literacy levels of adult primary care patients. Fam Med. 1991;23(6):433–5.

Parker RM, et al. The test of functional health literacy in adults: a new instrument for measuring patients’ literacy skills. J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):537–41.

Sabbahi DA, et al. Development and evaluation of an oral health literacy instrument for adults. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2009;37(5):451–62.

Cruz GD, et al. Determinants of oral health care utilization among diverse groups of immigrants in New York City. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(7):871–8.

Kohlenberger, J., et al., Barriers to health care access and service utilization of refugees in Austria: Evidence from a cross-sectional survey. Health Policy, 2019.

Lai DW, Hui NT. Use of dental care by elderly Chinese immigrants in Canada. J Public Health Dent. 2007;67(1):55–9.

Marino R, et al. Factors associated with self-reported use of dental health services among older Greek and Italian immigrants. Spec Care Dent. 2005;25(1):29–36.

Nguyen KYT, et al. Vietnamese oral health beliefs and practices: impact on the utilization of Western Preventive Oral Health Care. J Dent Hyg. 2017;91(1):49–56.

Okunseri C, et al. Hmong adults self-rated oral health: a pilot study. J Immigr Minor Health. 2008;10(1):81–8.

Vered Y, et al. Changing dental caries and periodontal disease patterns among a cohort of Ethiopian immigrants to Israel: 1999–2005. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:345.

Widstrom E, Nilsson B, Martinsson T. Use of dental services by Finnish immigrants in Sweden assessed by questionnaire. Scand J Soc Med. 1984;12(2):75–82.

Willis MS, Bothun RM. Oral hygiene knowledge and practice among Dinka and Nuer from Sudan to the U.S. J Dent Hygiene. 2011;85(4):306–15.

Xhihani B, et al. Oral Health Beliefs, Attitudes, and Practices of Albanian Immigrants in the United States. J Community Health. 2017;42(2):235–41.

Wu B, Tran TV, Khatutsky G. Comparison of utilization of dental care services among Chinese- and Russian-speaking immigrant elders. J Public Health Dent. 2005;65(2):97–103.

Gao X, et al. Oral health of foreign domestic workers: exploring the social determinants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2014;16(5):926–33.

Solyman M, Schmidt-Westhausen AM. Oral health status among newly arrived refugees in Germany: a cross-sectional study. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):132.

Boggess KA, et al. Oral hygiene practices and dental service utilization among pregnant women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(5):553–61.

Davidson PL, Andersen RM. Determinants of dental care utilization for diverse ethnic and age groups. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11(2):254–62.

Gilbert GH, et al. Dental health attitudes among dentate black and white adults. Med Care. 1997;35(3):255–71.

Payne BJ, Locker D. Preventive oral health behaviors in a multi-cultural population: the North York Oral Health Promotion Survey. J Can Dent Assoc. 1994;60(2):129–33.

Shelley D, et al. Ethnic disparities in self-reported oral health status and access to care among older adults in NYC. J Urban Health. 2011;88(4):651–62.

Boggess KA, et al. Knowledge and beliefs regarding oral health among pregnant women. J Am Dent Assoc. 2011;142(11):1275–82.

Junger ML, et al. Awareness among US adults of dental sealants for caries prevention. Prev Chronic Dis. 2019;16:E29.

Kiyak HA. Dental beliefs, behaviors and health status among Pacific Asians Caucasians. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1981;9(1):10–4.

Macek MD, et al. Oral health conceptual knowledge and its relationships with oral health outcomes: findings from a multi-site health literacy study. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2017;45(4):323–9.

Brega AG, et al. Association of ethnic identity with oral health knowledge, attitudes, behavior, and outcomes on the Navajo Nation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2019;30(1):143–60.

Lee J, Kiyak HA. Oral disease beliefs, behaviors, and health status of Korean-Americans. J Public Health Dent. 1992;52(3):131–6.

Atchison KA, Davidson PL, Nakazono TT. Predisposing, enabling, and need for dental treatment characteristics of ICS-II USA ethnically diverse groups. Adv Dent Res. 1997;11(2):223–34.

Gausman Benson J, Forman WB. Comprehension of written health care information in an affluent geriatric retirement community: use of the Test of Functional Health Literacy. Gerontology. 2002;48(2):93–7.

Gazmararian JA, et al. Health literacy among Medicare enrollees in a managed care organization. JAMA. 1999;281(6):545–51.

Institute of Medicine Committee on Health. In: Nielsen-Bohlman L, Panzer AM, Kindig DA, editors. Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. Washington: National Academies Press; 2004.

Mancuso JM. Assessment and measurement of health literacy: an integrative review of the literature. Nurs Health Sci. 2009;11(1):77–89.

Baker DW. The meaning and the measure of health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(8):878–83.

Kuhner MK, Raetzke PB. The effect of health beliefs on the compliance of periodontal patients with oral hygiene instructions. J Periodontol. 1989;60(1):51–6.

Barker T. Role of health beliefs in patient compliance with preventive dental advice. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22(5 Pt 1):327–30.

Sarria-Santamera A, et al. A systematic review of the use of health services by immigrants and native populations. Public Health Rev. 2016;37:28.

Mariño R, Morgan M, Hopcraft M. Transcultural dental training: addressing the oral health care needs of people from culturally diverse backgrounds. Commun Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2012;40(s2):134–40.

Wagner JA, Redford-Badwal D. Dental students’ beliefs about culture in patient care: self-reported knowledge and importance. J Dent Educ. 2008;72(5):571–6.

Dickson-Swift V, et al. Measuring oral health literacy: a scoping review of existing tools. BMC Oral Health. 2014;14:148.

Dwan K, et al. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(8):e3081.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. Funding was provided by the Innovation Fund of the Joint Federal Committee (G-BA) [Grant No. 01VSF17051].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Valdez, R., Spinler, K., Kofahl, C. et al. Oral Health Literacy in Migrant and Ethnic Minority Populations: A Systematic Review. J Immigrant Minority Health 24, 1061–1080 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01266-9

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-021-01266-9