Abstract

Personal growth initiative (PGI) refers to active and intentional participation in the growth process. PGI includes behavioral and cognitive skills and attitudes that are captured by four factors: Readiness for Change, Planfulness, Using Resources, and Intentional Behavior. There is substantial evidence supporting the positive relations between PGI and various domains of well-being. However, a lack of nuance regarding how the four facets of PGI differentially relate to other aspects of optimal functioning, such as coping, persists. Additionally, PGI has been theoretically tied to coping, but there is limited empirical evidence substantiating this link. Thus, the current study examined the relations between PGI and coping styles, strategies, and self-efficacy in a sample of 789 college students through a series of three canonical correlations. The findings indicated different combinations of the four aspects of PGI related significantly to 13 coping styles, three coping strategies, and three forms of coping self-efficacy. These findings have implications for both the theory and operationalization of PGI, such as the viability of the four separate aspects of PGI, as well as for the application of PGI and coping in college settings, including the development of trainings to increase PGI and adaptive aspects of coping.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The ability to engage in personal growth is an important aspect of being human (Rogers, 1965). As such, much attention has been paid in recent years to both people’s ability to engage in personal growth and its positive relation to mental health (see Weigold et al., 2020, for a meta-analysis). One conceptualization of active and intentional engagement in personal growth is personal growth initiative (PGI). PGI is a learned skillset comprised of cognitive and behavioral components that people use to grow in personally important domains (Robitschek, 1998; Robitschek et al., 2012). Theoretically, PGI is related positively to mental health by intentional growth-focused coping when dealing with life issues (Robitschek & Kashubeck, 1999); however, very few studies have examined how PGI relates to ways people might cope with stressful situations. Additionally, relatively few studies have focused on the four components of PGI separately instead of combining them into a total score. Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to investigate the relations between the four aspects of PGI and coping styles, coping strategies, and coping self-efficacy in college students, a population for which personal growth may be especially salient (Chickering, 1969; see Arnett, 2016).

1.1 Personal Growth Initiative

PGI refers to an individual’s engagement in the process of personal development (Robitschek, 1998). PGI has two core tenets: intentionality and transferability (Robitschek et al., 2012). Intentionality stipulates that the individual must be actively and consciously engaged in the change process. Those who are high in intentionality theoretically have lower levels of psychological distress due to actively working toward reducing stressful situations and engaging in activities to facilitate their own recovery (Robitschek & Kashubeck, 1999; see Ayub & Iqbal, 2012). Transferability indicates that PGI is broadly applicable, as the skills involved are not specific to a particular life domain (Robitschek, 1998; Robitschek et al., 2012).

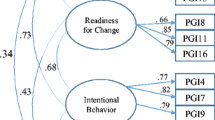

PGI was originally operationalized using the unidimensional Personal Growth Initiative Scale (Robitschek, 1998). More recently, the Personal Growth Initiative Scale – II (PGIS-II) was developed, partly to better elucidate the construct’s different cognitive and behavioral aspects. The two cognitive aspects of PGI are Readiness for Change (knowing when to start the growth process in a particular area) and Planfulness (making a plan to engage in growth and updating it as needed), and the two behavioral facets are Using Resources (using external sources of support when growing) and Intentional Behavior (engaging in one’s plan for growth; Robitschek et al., 2012; Robitschek & Thoen, 2015).

PGI has been heavily researched in college student populations, both in the United States and internationally, and has been shown to be an important predictor of optimal functioning (e.g., Cai & Lian, 2022; Taušová et al., 2019; Weigold et al., 2021). For example, Weigold et al. (2021) showed that PGI positively predicted basic needs satisfaction in college, as well as psychological well-being and vocational commitment, for United States college students attending either a public, predominantly White university or a private, minority-majority college. Taušová et al. (2019) found that PGI directly and negatively predicted mental health problems, as well as indirectly and negatively predicted acculturative stress through host culture orientation, in a sample of international students studying in the Netherlands. Finally, Cai and Lian (2022) showed that PGI positively predicted sense of purpose, both directly and indirectly through academic self-efficacy, in Chinese college students.

Most of the research on PGI, both involving college students and other populations, has used either the original unidimensional measure of PGI or the total score of the PGIS-II (see de Freitas et al., 2016; Weigold et al., 2020). This is partially consistent with the development article for the PGIS-II, which indicated that either total or subscale scores could be used (Robitschek et al., 2012), as well as research showing a bifactor model best underlies this measure such that items loaded both onto their specific subfactor and an overall PGI factor, the latter of which best represented the PGI construct (Weigold et al., 2018, 2023). However, this focus on total scores limits our understanding of how the four aspects of PGI might differentially contribute to optimal functioning, and researchers have called for additional studies in this area (Robitschek et al., 2012; Weigold et al., 2018).

Available studies have shown both similarities and differences among the four PGIS-II subscales (e.g., Chang et al., 2018; Malik et al., 2015; Yakunina et al., 2013). For example, Chang et al. (2018) found that, of the four facets, only Using Resources positively predicted additional variance in life satisfaction beyond gender and age in a sample of Chinese college students, whereas only Planfulness did so for United States college students. Additionally, Malik et al. (2015) showed that only Planfulness and Intentional Behavior correlated significantly with self-esteem and academic achievement in Pakistani technical institute students. Finally, Yakunina et al. (2013) found that Planfulness, acculturative stress, and the interaction between Using Resources and acculturative stress predicted psychological adjustment for international students studying in the United States. Taken together, these findings support the theoretical relation between intentional growth and well-being in college students, as well as the potential importance of the PGIS-II subscales in understanding the relations between PGI and other constructs. The current study sought to further examine the subscales of the PGIS-II in relation to coping.

1.2 Coping Styles, Strategies, and Self-Efficacy

Coping is defined as a person’s response to life problems and stress (Amirkhan, 1990; Carver et al., 1989). Two ways of assessing coping are dispositional coping styles and situational coping strategies. Coping styles refer to ways in which people typically handle life issues, whereas coping strategies are the actual coping mechanisms used to deal with a specific issue (Carver & Scheier, 1994). Coping styles and strategies are “related but not redundant” (Bouchard et al., 2004, p. 236), and both can affect how a person handles a particular situation (Carver & Scheier, 1994). Coping styles and strategies are often divided into either broad categories, such as problem-focused (efforts to deal directly with the stressor or its source), emotion-focused (efforts to reduce emotional reactions to the stressor), and avoidant (efforts to distract from or not think about the stressor), or more specific constructs, such as restraint (patiently waiting for the best time to actively focus on the stressor) and denial (pretending that a stressor does not exist). Depending on the specific situation, these styles and strategies can also be considered either adaptive (helpful ways of dealing with the stressor) or maladaptive (problematic ways of handling the stressor; Carver et al., 1989).

A large literature base has shown that coping styles and strategies relate to mental health. For example, a meta-analysis involving 151 samples from 44 countries indicated that problem-focused coping styles related weakly and negatively, and avoidant coping styles related moderately and positively, to anxiety and depression during the first part of the COVID-19 pandemic (Cheng et al., 2024). Research on college students specifically has found that engaging in problem-focused coping is positively related to aspects of well-being, and engaging in avoidant coping is positively related to aspects of distress (e.g., Freire et al., 2016; Gustems-Carnicer & Calderón, 2013; Krypel & Henderson-King, 2010). For instance, in their study of coping styles in United States college students, Krypel and Henderson-King (2010) found that problem-focused coping was positively related to optimism and negatively related to perceived stress, whereas disengaged coping showed the opposite relation to optimism and perceived stress; emotion-focused coping was not significantly related to either outcome. Additionally, Gustems-Carnicer and Calderón (2013) found that the problem-focused coping strategies of positive reappraisal and problem-solving were negatively related to symptoms of psychological distress, whereas the avoidant strategies of cognitive avoidance, resignation, seeking alternate rewards, and emotional discharge were positively related to distress symptoms, in a sample of Spanish teacher education students. Finally, Freire (2016) showed that Spanish students with higher psychological well-being profiles were more likely to engage in the academic-related coping strategies of planning, positive reappraisal, and support-seeking compared to those with lower psychological well-being profiles.

A construct closely related to coping styles and strategies is coping self-efficacy, which refers to a person’s confidence in their ability to successfully engage in coping behaviors during stressful situations (Chesney et al., 2006). Coping self-efficacy has long been a prominent part of self-efficacy theory and research. For instance, Bandura (1982) discussed how higher levels of coping self-efficacy positively predict both persistence and successful performance, whereas lower levels of coping self-efficacy positively predict anxiety about upcoming stressful situations.

Research has shown that coping self-efficacy generally relates significantly and positively to problem-focused coping styles and strategies, as well as negatively to emotion-focused coping styles and avoidant coping strategies (Chesney et al., 2006; Delahaij & Van Dam, 2017; Nicholls et al., 2010). For example, Chesney et al. (2006) found that, in a sample of HIV-seropositive gay men in the United States, problem-focused coping self-efficacy was positively related to the positive reappraisal and planful problem-solving coping styles; additionally, confidence for stopping unpleasant thoughts was positively associated with the distancing coping style and negatively associated with the cognitive escape-avoidance coping style, and confidence in one’s ability to seek out social support was negatively related to the distancing coping style and positively related to coping by seeking social support. Delahaij and Van Dam (2017) showed that coping self-efficacy indirectly predicted problem-focused and emotion-focused coping styles through threat and challenge emotions in a sample of military recruits in the Netherlands. Finally, Nicholls et al. (2010) found that coping self-efficacy was a positive predictor of coping effectiveness in athletes who were engaged in a competitive event; this relationship was partially mediated by the task-oriented and disengagement-oriented coping strategies the athletes used during the event.

In addition to being related to coping styles and strategies, coping self-efficacy has also been linked to positive mental health in both college student and other samples (Chesney et al., 2006; Shahrour & Dardas, 2020; Shigemoto & Robitschek, 2021). For example, Chesney and colleagues (2006) found that confidence for engaging in problem-focused coping, stopping unpleasant thoughts, and seeking social support were all positively related to positive morale and positive states of mind, as well as negatively related to anxiety, burnout, negative morale, and perceived stress, in HIV-seropositive gay men in the United States. Additionally, Shahrour and Dardas (2020) showed that trauma coping self-efficacy was a negative predictor of psychological distress in a sample of Jordanian nurses working in hospitals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Finally, Shigemoto and Robitschek (2021) found that trauma coping self-efficacy was negatively related to posttraumatic stress symptoms in United States college students who had potentially experienced a traumatic event.

Taken together, coping styles, strategies, and self-efficacy are important predictors of mental health (e.g., Cheng et al., 2024; Chesney et al., 2006; Gustems-Carnicer & Calderón, 2013). However, they have seldom been examined in relation to PGI, particularly in college student samples.

1.3 PGI and Coping in College Students

Both traditional and non-traditional college students experience multiple stressors within the college environment, such as academic pressure, financial issues, and role changes (Pedrelli et al., 2015). As such, responding to these stressors and engaging in personal growth “are inherent parts of the college experience” (Robitschek & Thoen, 2015, p. 219). However, many college students struggle with their ability to cope with such stressors, potentially resulting in issues with mental health and substance use, foreclosing on career decisions, and/or leaving college altogether (Pedrelli et al., 2015; Robitschek & Thoen, 2015). Given the importance of PGI to psychological well-being and vocational development in students (e.g., Weigold et al., 2021), it is necessary to determine how PGI relates to coping with college challenges.

Only a handful of published studies have explored how PGI relates to coping styles, strategies, or self-efficacy in college students (Gregor et al., 2021; Robitschek & Cook, 1999; Shigemoto & Robitschek, 2021; Weigold & Robitschek, 2011). The available literature has generally shown positive relations between PGI and problem-focused aspects of coping, as well as negative relations between PGI and avoidant aspects. For example, Robitschek and Cook (1999) found that PGI was significantly and positively related to having a reflective coping style, and significantly and negatively related to having a suppressive coping style, in United States college students. Additionally, Weigold and Robitschek (2011) showed that having a problem-focused coping style mediated the relationship between PGI and trait anxiety in United States college students such that PGI positively predicted problem-focused coping which, in turn, negatively predicted anxiety. Regarding coping self-efficacy, Gregor et al. (2021) found that PGI positively predicted self-efficacy for coping with career barriers in a sample of United States community college students. Finally, Shigemoto and Robitschek (2021) showed that the four aspects of PGI all related positively and significantly to trauma coping self-efficacy in United States college students who had experienced potentially traumatic events.

Literature in other adult samples has yielded similar results. For instance, Szymanski et al. (2017) indicated that PGI moderated the relationship between the discrimination coping strategy of education/advocacy and both self-awareness and commitment to social justice in LGB adults in the United States. Saranjam et al. (2019) found that PGI was a significant and positive predictor of coping self-efficacy in Iranian cancer patients.

Taken together, there is a paucity of research on the relation between PGI and coping. Of the available studies, two used the current PGIS-II (Shigemoto & Robitschek, 2021; Szymanski et al., 2017), with only Shigemoto and Robitschek (2021) examining its subscales. Additionally, coping was typically examined using broad definitions (e.g., problem-focused coping, a total score for coping self-efficacy), rather than by multiple specific constructs (e.g., acceptance, self-efficacy for using social support). As a result, more nuanced relations among the four facets of PGI and specific aspects of coping have yet to be explored.

1.4 The Current Study

Through the current study, we sought to add to the literature on PGI and coping in college students by examining the four aspects of PGI (Readiness for Change, Planfulness, Using Resources, and Intentional Behavior) as they related to diverse coping styles, strategies, and self-efficacy. We also added to the call for studies explicitly examining how the four facets of PGI might relate differentially to other constructs (Robitschek et al., 2012; Weigold et al., 2018), which would have implications for both PGI theory and operationalization.

To examine the relation between PGI and coping, we ran a series of three canonical correlations, one each involving coping styles, strategies, and self-efficacy. Based on prior literature (e.g., Shigemoto & Robitschek, 2021), we hypothesized that there would be at least one significant canonical function per analysis in which the four PGI factors would positively relate to problem-focused and social support-oriented aspects of coping and negatively relate to avoidant forms of coping. Given the lack of literature, we did not make other hypotheses, although we expected there would be additional significant canonical functions indicating that the four facets of PGI would relate differentially to various forms of coping styles, strategies, and self-efficacy.

2 Method

2.1 Participants

We recruited college students from human subjects pools at two institutions using purposive sampling. Students needed to be 18 years or older and enrolled in at least one college class to participate in the study. The final sample consisted of 789 college students gathered from two schools of higher education: a large, public university (n = 658, 83.4%) and a small, private, liberal arts college (n = 131, 16.6%). Canonical correlation typically requires large sample sizes, and suggested estimates range from at least 20 participants per variable to between 40 and 60 per variable (see Fan & Konald, 2010). Consequently, we collected data until we had at least 40 cases per variable for the canonical correlation with the most variables. As the maximum number of variables possible for one of our canonical correlations was 19, our final sample size of 789 (41.5 cases per variable) met this requirement.

Of our 789 participants, over two-thirds identified as women (n = 548, 69.5%), and the others identified as men (n = 239, 30.3%) or chose not to answer (n = 2, 0.3%). Participants primarily identified as European American/White (n = 598, 75.8%), followed by African American/Black (n = 83, 10.5%), Biracial or Multiracial (n = 31, 3.9%), Asian/Asian American (n = 23, 2.9%), Latin American/Hispanic (n = 20, 2.5%), Native American (n = 3, 0.4%), Other (n = 27, 3.4%), or chose not to respond (n = 4, 0.5%). Year in school was roughly evenly split among Freshman (n = 246, 31.2%), Sophomore (n = 196, 24.8%), Junior (n = 167, 21.2%), and Senior (n = 168, 21.3%), with a small amount identifying as Graduate (n = 2, 0.3%) or Other (n = 10, 1.3%). Ages ranged from 18 to 49 (M = 21.18, SD = 4.38). As it was not possible for us to know how many students were involved in the human subjects pools and, of those, how many were eligible to participate (i.e., at least 18 years old), we were not able to calculate a response rate. However, the number of participants corresponded to approximately 2.4% of the undergraduate population at the university and 6.7% at the college.

3 Measures

3.1 Personal Growth Initiative

Personal growth initiative was measured using the Personal Growth Initiative Scale – II (PGIS-II; Robitschek et al., 2012). This is a 16-item scale consisting of four subscales assessing cognitive and behavioral facets of the active and intentional growth process. The two cognitive subscales are Readiness for Change (4 items examining knowledge of when a person is ready to start the growth process) and Planfulness (5 items measuring a person’s ability to plan for the growth process). The two behavioral subscales are Using Resources (3 items assessing a person’s use of external resources when engaging in growth) and Intentional Behavior (4 items examining a person’s engagement in growth behaviors). Participants responded to items using a six-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (Disagree Strongly) to 5 (Agree Strongly). Scores were averaged, with higher scores indicating higher levels of each subscale. Sample items include “I figure out what I need to change about myself” and “I look for opportunities to grow as a person” (Robitschek et al., 2012, p. 287).

Research has shown adequate to strong evidence for the PGIS-II’s scores’ reliability and validity. Confirmatory factor analysis showed support for a bifactor model consisting of the four subscales and an overall score in samples of college students, Mechanical Turk workers, and therapy clients (Weigold et al., 2018). The PGIS-II’s subscale scores have correlated positively and significantly with the original Personal Growth Initiative Scale and a measure of general self-efficacy in college student samples; they have also evidenced small correlations with social desirability (Robitschek et al., 2012; Weigold et al., 2014). The total score has shown good test-retest reliability for up to six weeks (6-week r = .62; Robitschek et al., 2012). In the current study, both Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega levels were good (see Table 1).

3.2 Coping Styles

Coping styles were assessed using the COPE Inventory (Carver et al., 1989). The COPE Inventory is a 60-item measure of 15 coping styles assessed by four items each: Positive Reinterpretation and Growth (emotion-focused tactic of viewing stressors as growth opportunities), Mental Disengagement (distracting oneself from the stressor), Focus On and Venting of Emotions (both feeling and expressing emotions related to the stressor), Use of Instrumental Social Support (problem-focused use of support for assistance), Active Coping (effortful, direct coping with a stressor), Denial (pretending the stressor does not exist), Religious Coping (using religion to deal with the stressor), Humor (making light of the stressor), Behavioral Disengagement (giving up on dealing with the stressor), Restraint (waiting for the right moment to engage in active coping), Use of Emotional Social Support (emotion-focused use of support for sympathy), Substance Use (using alcohol or drugs), Acceptance (accepting that the stressor exists), Suppression of Competing Activities (stopping other activities to focus on the stressor), and Planning (cognitively making plans to deal with the stressor). Participants were asked to indicate the degree to which they usually used each style to deal with stressful events using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (I usually don’t do this at all) to 4 (I usually do this a lot). Scores were averaged, with higher scores indicating greater use of that style. Sample items include “I discuss my feelings with someone” and “I do what has to be done, one step at a time” (Carver, n.d.).

The COPE Inventory (along with its short forms) is one of the most popular measures of coping (see Kato, 2013). Carver et al. (1989) found support for the factor structure of the original 14 subscales (which did not include Humor), and Carver (n.d.) recommended that the different styles of coping be examined separately. These subscale scores showed evidence of adequate to good test-retest reliability for up to eight weeks (r range = 0.46 to 0.86). They also correlated as expected with measures of optimism, self-esteem, hardiness, Type A personality, and social desirability, showing adequate evidence of convergent and discriminant validity (Carver et al., 1989). In the current study, 11 of the 15 subscales had adequate or above levels of Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega, two had marginal levels, and two had poor levels (see Table 1). The two subscales with poor alpha and omega levels, Mental Disengagement and Suppression of Competing Activities, were not included in further analyses.

3.3 Coping Strategies

Coping strategies were assessed using the Coping Strategy Indicator (CSI; Amirkhan, 1990). The CSI is a 33-item measure assessing three coping strategies with 11 items each: Problem-Solving (focusing on the stressor), Seeking Social Support (seeking support from others when dealing with the stressor), and Avoidant (withdrawing from the stressor). Participants were asked to think of a stressful problem they experienced over the past six months and answer questions about how they coped with the problem using a three-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 3 (A lot). Scores were averaged, with higher scores indicating higher use of that coping strategy. Sample items include “Tried to solve the problem” and “Daydreamed about better times” (Amirkhan, 1990, p. 1070).

The CSI’s scores have shown adequate to strong evidence of reliability and validity. Confirmatory factor analysis has supported the three-factor structure, and the scores have correlated as expected with the scores of other coping measures (Amirkhan, 1990; Clark et al., 1995) and social desirability (Amirkhan, 1990), showing support for convergent and discriminant validity. Additionally, the scores changed as a response to intervention, such that Problem-Solving and Seeking Social Support scores increased, and Avoidant scores decreased (Amirkhan, 1994). The scores showed evidence of good test-retest reliability in college students for time periods between four to six weeks (r range = 0.80 to 0.83; Amirkhan, 1990). Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega levels for the current study were all strong (see Table 1).

3.4 Coping Self-Efficacy

Coping self-efficacy was measured using the Coping Self-Efficacy Scale (CSES; Chesney et al., 2006), a 13-item measure assessing confidence in one’s ability to engage in three types of coping: Use Problem-Focused Coping (6 items; confidence one can actively deal with stressors), Stop Unpleasant Thoughts and Emotions (4 items; confidence one can handle their cognitive and emotional states related to stressors), and Get Support from Friends and Family (3 items; confidence one can seek and find social support when dealing with stressors). Participants responded to items assessing their confidence using the three types of coping on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (Cannot do at all) to 10 (Certain can do). Scores were averaged, with higher scores indicating higher confidence for each type of coping. Sample items include “Leave options open when things get stressful” and “Make unpleasant thoughts go away” (Chesney et al., 2006, p. 425).

The CSES’s scores have shown good evidence of reliability and validity. The three-factor structure has been confirmed (Chesney et al., 2006; Cunningham et al., 2020). Additionally, the subscale’s scores correlated as expected with aspects of well-being and distress, showing evidence of concurrent validity (Chesney et al., 2006; Cramer et al., 2017), as well as related coping strategies, indicating convergent validity. The scores also showed adequate to good test-retest reliability estimates for periods of three (r range = 0.52 to 0.68), six (r range = 0.54 to 0.68), and 12 months (r range = 0.40 to 0.49; Chesney et al., 2006). Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega levels for the current study were adequate to strong (see Table 1).

3.5 Procedure

The Institutional Review Boards at both institutions approved the study prior to data collection. Participants were recruited through the human subjects pools in the Department of Psychology at both institutions, through which students could receive course or extra credit for participating in research. Human subjects pools are systems through which departmental researchers can recruit student participation in research studies; students learn about the system from their instructors in participating psychology classes. Data were collected over several semesters prior to the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. At the university, interested participants were provided a link to a SurveyMonkey website that they could access at a time and location of their choice. Upon accessing the website, participants were provided with the consent form, counterbalanced questionnaires, and demographics. At the college, interested students were also given the SurveyMonkey link, although they completed the study using a computer in the researcher’s lab. Upon completion of the study, all participants received a debriefing.

3.6 Study Design and Data Analyses

We used a correlational survey design, as we were interested in both collecting data on participants’ self-reported experiences and examining relations among variables. We planned to examine patterns of relations between sets of variables, specifically the four aspects of PGI with the 13 coping styles, three coping strategies, and three types of coping self-efficacy. As a result, our main analyses consisted of three canonical correlations. Canonical correlation is a multivariate analytic technique, based on the general linear model, that investigates how different combinations of variables (canonical functions) from two variable sets underlie the relation between those two variable sets (Fan & Konald, 2010).

Canonical correlation is sensitive to both missing data and outliers, as well as the assumptions of linearity, homoscedasticity, normality, and multicollinearity (Hair et al., 1998). Consequently, prior to conducting the main analyses, we screened our dataset for these issues. Additionally, we calculated the means and standard deviations for the main variables. We assessed the hypotheses by running three canonical correlations using SPSS v29. For all three canonical correlations, the four aspects of PGI comprised Set 1. Set 2 was comprised of the 13 coping styles for the first canonical correlation, the three coping strategies for the second canonical correlation, and the three types of coping self-efficacy for the third canonical correlation. We interpreted the canonical loadings using a value of 0.30 to denote which variables loaded significantly (Meloun & Militký, 2011). We named each of the significant functions based on the highest-loading variables.

4 Results

4.1 Preliminary Analyses

Initially, 912 people accessed the study. After removing those who did not complete most of the survey (n = 73, 8.0%), were not at least 18 years old (n = 7, 0.1%), or showed evidence of random responding (n = 42, 4.6%), 790 participants remained. We then screened the dataset for missing items, outliers, linearity, homoscedasticity, normality, and multicollinearity. The amount of missing data was low, with 99.7% of the 96,380 data points completed. Consequently, we used Available Item Analysis to account for missing data (Parent, 2013). After examining both Mahalanobis distance and Cook’s distance, we removed one participant as a potentially influential multivariate outlier. Scatterplots of all bivariate correlations indicated the assumptions of linearity and homoscedasticity were met. Regarding normality, three of the coping styles (Denial, Behavioral Disengagement, and Substance Use) had histograms indicating substantive positive skew. However, transformations were ineffective in reducing the skew, and none of the variables had a skew value above │2│ or a kurtosis value above │7│ (Kim, 2013); therefore, the original variables were used in all analyses. There was no evidence of multicollinearity, as bivariate correlations were not large (none ≥ 0.80), tolerance values were all > 0.10, and variance inflation factors were all < 5.00 (Daoud, 2017).

Means, standard deviations, and internal consistency estimates for the final variables are shown in Table 1. On average, participants reported moderate-to-high levels of PGI. For coping styles, participants endorsed using Planning and Positive Reinterpretation and Growth the most often and Substance Use, Behavioral Disengagement, and Denial the least often. Participants also reported moderate-to-high use of the three coping strategies (Problem-Solving, Seeking Social Support, and Avoidant). Finally, participants indicated having moderate-to-high coping self-efficacy.

4.2 Main Analyses

4.2.1 Coping Styles

We performed a canonical correlation to examine the potential patterns of relations (canonical functions) among the aspects of PGI and coping styles. The four facets of PGI (Readiness for Change, Planfulness, Using Resources, and Intentional Behavior) comprised the Set 1 variables, and the 13 coping styles (Positive Reinterpretation and Growth, Focus On and Venting of Emotions, Use of Instrumental Social Support, Active Coping, Denial, Religious Coping, Humor, Behavioral Disengagement, Restraint, Use of Emotional Social Support, Substance Use, Acceptance, and Planning) comprised the Set 2 variables. The maximum possible number of significant canonical functions is equal to the number of variables in the smaller set (in this case, four). All four canonical functions were significant; canonical loadings for these functions are shown in Table 2.

First Function: Growth-Oriented Coping. The first function was significant (Wilks’ Λ = 0.45, F(52, 2992.05) = 13.19, p < .001, Rc = 0.66, 44.0% explained variance). Lower levels of Readiness for Change (-0.77), Planfulness (-0.93), Using Resources (-0.51), and Intentional Behavior (-0.91) were associated with lower levels of Positive Reinterpretation and Growth (-0.83), Use of Instrumental Social Support (-0.35), Active Coping (-0.80), Restraint (-0.32), Acceptance (-0.41), and Planning (-0.81), as well as higher levels of Denial (0.31) and Behavioral Disengagement (0.45). The remaining five coping styles did not have significant loadings (range = 0.09 to − 0.29). As the direction of correlations can be reversed (i.e., as X decreases, Y increases is consistent with as X increases, Y decreases), this function denotes that people who are high in all aspects of PGI are likely to acknowledge stressors and cope with them in an intentional, active way.

Second Function: Support-Oriented Coping. The second function was also significant (Wilks’ Λ = 0.35, F(36, 2284.64) = 4.93, p < .001, Rc = 0.38, 14.6% explained variance). Lower levels of Using Resources (-0.83) were related to lower levels of Focus On and Venting of Emotions (-0.54), Use of Instrumental Social Support (-0.82), Denial (-0.34), Religious Coping (-0.38), Behavioral Disengagement (-0.39), and Use of Emotional Social Support (-0.79). The remaining three PGI facets and seven coping styles did not have significant loadings (range = 0.01 to − 0.24). Reversing the direction of the loadings, this pattern denotes that people who are high in using external sources of support when growing tend to also use external support when coping with stressors while simultaneously distancing themselves from the stressors.

Third Function: Behavioral-Oriented Growth Opportunity. The third function was also significant (Wilks’ Λ = 0.14, F(22, 1548) = 2.25, p < .001, Rc = 0.20, 3.8% explained variance). Higher levels of Readiness for Change (0.35) and Planfulness (0.34), combined with lower levels of Intentional Behavior (-0.33), were related to lower levels of Positive Reinterpretation and Growth (-0.47). The remaining aspect of PGI and 12 coping styles did not have significant loadings (range = 0.02 to 0.23). Reversing the signs, these findings indicate that people who are higher in behavioral engagement with the growth process while simultaneously being lower in cognitive engagement are more likely to view stressors as opportunities for growth.

Fourth Function: Reality-Oriented Coping. The final function was also significant (Wilks’ Λ = 0.04, F(10, 775) = 1.87, p = .046, Rc = 0.15, 2.3% explained variance). Lower levels of Readiness for Change (-0.54) were associated with lower levels of Focus On and Venting of Emotions (-0.52) and Acceptance (-0.41), as well as higher levels of Denial (0.49). The remaining three aspects of PGI and ten coping styles did not have meaningful loadings (range = − 0.01 to − 0.26). Reversing the signs, these findings indicate that people who know when they are ready to start the growth process also focus on the reality of stressors and vent their feelings.

4.3 Coping Strategies

When completing the measure of coping strategies, participants focused on one event they had recently experienced that they felt was stressful. These self-reported stressors varied across participants and included receiving a speeding ticket, making a presentation, ending a relationship, and the death of a loved one.

We ran a canonical correlation to examine the relations among the four facets of PGI in Set 1 and the three coping strategies (Problem-Solving, Seeking Social Support, and Avoidant) in Set 2. As Set 2 consisted of three variables, the maximum number of canonical functions was three. Two were significant, and their canonical loadings are shown in Table 3. The third was negligible and did not yield an F-statistic (Wilks’ Λ = 1.00, Rc = 0.06, 0.0% explained variance).

First Function: Self-Reliant Situational Coping. The first canonical function was significant (Wilks’ Λ = 0.92, F(12, 2069.27) = 5.70, p < .001, Rc = 0.25, 6.3% explained variance). Lower Readiness for Change (-0.68), Planfulness (-0.77), and Intentional Behavior (-0.65) were associated with lower levels of Problem-Solving (-0.59) and higher levels of both Seeking Social Support (0.34) and Avoidant (0.59). Using Resources did not have a significant loading (-0.11). When reversing the signs, these findings indicate that those who engage in the cognitive and general behavioral aspects of the growth process are more likely to focus on the specific stressor and engage in problem-solving behaviors, although they are simultaneously less likely to reach out to others for support in this process.

Second Function: Supported Situational Coping. The second canonical function was also significant (Wilks’ Λ = 0.06, F(6, 1566) = 2.86, p = .009, Rc = 0.13, 1.8% explained variance). Lower levels of Readiness for Change (-0.60), Planfulness (-0.62), Using Resources (-0.94), and Intentional Behavior (-0.38) were related to lower levels of Problem-Solving (-0.66) and Seeking Social Support (-0.94). Avoidant did not load significantly (0.16). When the signs are reversed, these results indicate that people who are high in PGI, particularly Using Resources, are more likely to both actively focus on a stressor and use social support to cope with it.

4.4 Coping Self-Efficacy

Finally, we ran a canonical correlation to examine the relations between the four aspects of PGI in Set 1 and the three types of coping self-efficacy (Use Problem-Focused Coping, Stop Unpleasant Thoughts and Emotions, and Get Support from Friends and Family) in Set 2. The maximum number of canonical functions was three. Two canonical functions were significant, and their canonical loadings are found in Table 4. The third was negligible and did not yield an F-statistic (Wilks’ Λ = 0.99, Rc = 0.12, 1.4% explained variance).

First Function: Growth-Related Self-Efficacy. The first canonical function was significant (Wilks’ Λ = 0.56, F(12, 2069.27) = 41.97, p < .001, Rc = 0.62, 38.8% explained variance). Lower levels of Readiness for Change (-0.82), Planfulness (-0.94), Using Resources (-0.63), and Intentional Behavior (-0.88) were related to lower levels of Use Problem-Focused Coping (-0.96), Stop Unpleasant Thoughts and Emotions (-0.70), and Get Support from Friends and Family (-0.78). Reversing the signs, these results indicate that people who are high in PGI are also confident in their ability to cope with stressors by both using a problem-focused approach and reaching out to others; they are also confident they can effectively handle negative thoughts and feelings associated with stressors.

Second Function: Support-Related Self-Efficacy. The second canonical function was also significant (Wilks’ Λ = 0.36, F(6, 1566) = 11.24, p < .001, Rc = 0.26, 6.8% explained variance). Higher levels of Using Resources (0.67) were related to higher levels of Get Support from Friends and Family (0.62). The remaining PGI facets and coping self-efficacy types did not load significantly (range = − 0.03 to − 0.29). These findings suggest that those who are more likely to use external resources during the growth process are also more confident in their ability to find and use social support when coping with stressors.

5 Discussion

A robust literature base has shown PGI to be positively related to well-being and negatively related to distress (see Weigold et al., 2020). This link is theorized to occur due to individuals with higher levels of PGI being more likely to engage in intentional and adaptive coping mechanisms than those with lower levels (Robitschek & Kashubeck, 1999). In the current study, we sought to add to the limited literature examining PGI in relation to coping styles, strategies, and self-efficacy by running three canonical correlations. Aligned with past research on the four facets of PGI (e.g., Robitschek et al., 2012; Weigold et al., 2018), we expected significant canonical functions in which all four aspects of PGI would be significantly and positively related to problem-focused and social support-oriented aspects of coping, as well as negatively related to avoidant aspects of coping. We also expected that different combinations of the four aspects of PGI would differentially relate to various facets of coping.

Our hypothesis regarding the significant, positive relations of the four facets of PGI to problem-focused and social support-oriented aspects of coping, as well as negative relations to avoidant aspects of coping, was supported for all three canonical correlations. For coping styles, the significant canonical function involving the four facets of PGI (Growth-Oriented Coping) accounted for 44.0% of the variance across variables; for coping self-efficacy, the relevant significant canonical function (Growth-Related Self-Efficacy) explained 38.8% of the variance. However, for coping strategies, the relevant significant canonical function (Supported Situational Coping) accounted for only 1.8% of the variance across variables. There are several potential reasons for these different findings. First, PGI is considered “a developed set of skills for self-improvement” in areas salient to the person (Robitschek et al., 2012, p. 274). It is possible that the specific stressful situations with which individuals were coping were not viewed as providing opportunities for relevant self-improvement. Relatedly, PGI might be more strongly related to coping styles and self-efficacy than strategies given the more general nature of the former two constructs. This is consistent with the relation between coping styles and strategies being generally positive and moderate, but not strong (Carver et al., 1989). Finally, self-efficacy theoretically partially underlies PGI (Robitschek, 1998), which may explain PGI’s stronger relation to coping self-efficacy compared to coping strategies.

As expected, in addition to the canonical functions involving all facets of PGI, significant patterns also emerged for specific aspects of PGI. First, the canonical correlations involving coping styles and self-efficacy (but not coping strategies) each had one significant canonical function on which Using Resources was the only aspect of PGI to load significantly. For coping styles, Using Resources was positively related to coping involving social support and problem avoidance (Support-Oriented Coping), whereas for coping self-efficacy, Using Resources was positively related to efficacy for garnering social support (Support-Related Self-Efficacy). It is unsurprising that Using Resources was related to social support-focused coping, as it is the only aspect of PGI that explicitly involves using resources outside of the self (Robitschek et al., 2012). Additionally, since its operationalization, Using Resources has behaved somewhat differently than the other three facets of PGI, both in its relations to other variables and how its items load onto the PGI bifactor structure (e.g., Robitschek et al., 2012; Weigold et al., 2018). Therefore, it is not unexpected that this aspect of PGI would be by itself in significant canonical functions. However, it is unclear why Using Resources would relate positively to avoidant coping styles. It is possible that those who know how and when to use support when growing but do not necessarily intentionally engage in other aspects of the growth process might also prefer not to directly engage with the stressful situations they encounter.

Second, and related to the above pattern, the canonical correlations involving coping styles and strategies (but not coping self-efficacy) each had a significant canonical function that involved all aspects of PGI except Using Resources. For coping styles, higher levels of Intentional Behavior, coupled with lower levels of both Readiness for Change and Planfulness, were related to Positive Reinterpretation and Growth (Behavioral-Oriented Growth Opportunity). This pattern indicates that those who intentionally engage in growth behaviors without knowing when to change or developing a plan to do so are more likely to view stressful situations as growth opportunities. It is possible that these individuals may view most life situations as growth opportunities, rather than only those that specifically fit with how and when they want to change. Conversely, this pattern might represent people who are in the action stage of the stages of change represented by the Transtheoretical Model and have already passed through the precontemplation and contemplation stages (Velicer et al., 1998). In this case, individuals may have previously focused on the cognitive components of PGI and are now more attuned to relevant opportunities for behaviorally engaging in growth.

The significant canonical function between coping strategies and Readiness for Change, Planfulness, and Intentional Behavior had somewhat different loadings than the canonical function involving coping styles and the same three aspects of PGI. For coping strategies, higher levels of Readiness for Change, Planfulness, and Intentional Behavior were related to higher levels of problem-focused coping, as well as lower levels of both social support and avoidant coping (Self-Reliant Situational Coping). This can be contrasted with the previously discussed coping strategies canonical function that involved all four aspects of PGI (Supported Situational Coping). In that function, higher levels of all PGI factors were related to higher levels of both problem-focused and social support coping but no longer related to lower levels of avoidant coping. Examined together, these functions lend support to the aforementioned pattern of Using Resources being simultaneously positively related to coping styles involving social support and avoidant behaviors. However, the actual variance accounted for across variables was low for both significant coping strategies functions, so these results should be interpreted with caution.

Finally, a coping styles pattern emerged such that Readiness for Change was positively related to both Acceptance and Focusing On and Venting of Emotions while simultaneously being negatively related to Denial (Reality-Oriented Coping). This denotes a pattern by which people who know when they are ready to make changes (regardless of whether they follow through with such changes) tend to accept the reality of stressors, as well as vent their emotions about the stressors. Readiness for Change involves both knowing in which areas one wants to change and whether it is the right time to do so (Robitschek & Thoen, 2015). It is possible that a tendency to be aware of when to change increases a person’s ability to recognize that a stressor exists, even if the person does not like it. Conversely, accepting that stressors are present and emotionally difficult may encourage a person to think about whether changes to themselves are warranted. However, the variance accounted for by this pattern was low, so further studies on its relevance are needed.

Taken together, these findings provide evidence that PGI is generally positively related to problem-focused and social support-oriented, as well as negatively related to avoidant, coping styles, strategies, and self-efficacy, which supports past findings (e.g., Gregor et al., 2021; Robitschek & Cook, 1999). As one of the only studies examining the four aspects of PGI in relation to coping (see Shigemoto & Robitschek, 2021, for an exception), the results also provide much-needed information on how the different facets of PGI add nuanced information about the relation between PGI and coping in college students.

5.1 Implications and Future Directions

The findings from the current study have several implications for working with college students. First, PGI levels may be a useful indicator of how students are likely to cope with the stressors of college. In their literature review, Robitschek and Thoen (2015) outlined several ways that PGI assessment might be incorporated into college and university settings, such as in counseling centers to determine readiness for change prior to therapy, career services to examine which aspects of career development may be most suitable for a particular student (e.g., in-depth or in-breadth exploration), and academic advising to determine which students are most likely to proactively seek outside resources as needed during their academic journey. Relatedly, trainings have recently been developed to increase PGI in college students (Meyers et al., 2015; Thoen & Robitschek, 2013). These trainings may be incorporated into college settings, such as during first-year orientations, to aid in facilitating problem-focused and support-oriented coping. However, the outcomes of these trainings have not yet been assessed in relation to coping, so future research is needed to examine this assertion.

In general, results indicated that higher levels of PGI were positively related to problem-focused and social support-oriented coping and either negatively or not related to avoidant coping. Consequently, those working with college students might attempt to help them foster all aspects of PGI (Robitschek & Thoen, 2015). However, of the four PGI factors, Using Resources is most strongly related to coping that involves external sources of support. Consequently, students who are lower in Using Resources may be less likely than those who are higher in this aspect of PGI to let others know when they are struggling or use available campus resources to handle stressful situations. In these cases, it may be important for instructors and academic advisors to teach students not just about available campus resources but how they can be accessed and used (Robitschek & Thoen, 2015). However, Using Resources is also more strongly related to denying that stressors exist, so students high in this aspect may not always recognize stressful situations. Readiness for Change might help to counteract this, so people who work closely with students on the growth process, such as counseling center staff, might assist students who are high in Using Resources to also increase their Readiness for Change.

Given the correlational nature of the current study, it is also possible that experiences with different forms of coping may lead students to develop higher levels of PGI. For example, Intentional Growth Training (IGT), an intervention designed to increase PGI, showed that college students’ PGI increased after completing an activity that was outside their comfort zone (Thoen & Robitschek, 2013). Although not assessed, engaging in such an activity likely created some stress for students, potentially necessitating the use of coping strategies. Perhaps teaching students about aspects of coping with which they are unfamiliar and incorporating those into PGI training would facilitate development of both PGI and coping mechanisms. Such training may also lead to an increase in coping self-efficacy, given the importance of successful past experiences on self-efficacy development (Bandura, 1982). Additionally, as self-efficacy partially underlies PGI (Robitschek, 1998), it is possible that higher levels of coping self-efficacy might predict higher confidence in one’s ability to engage in both the coping and change processes.

Finally, the results also have implications for the PGIS-II. Analyses of the bifactor structure have indicated that an overall PGI factor may be the best representation of the PGI construct (Weigold et al., 2018, 2023), although some research has indicated the four subscales have unique associations with other constructs (e.g., Chang et al., 2018; Malik et al., 2015). The current study shows evidence that higher PGIS-II subscale scores are associated with problem-focused and social support-oriented coping styles, strategies, and self-efficacy. However, it also shows that various combinations of the PGIS-II subscale scores (often, but not always, involving Using Resources) relate differentially to various forms of coping. Together, these provide evidence for both the potential meaningfulness of an overall PGI factor and additional information provided by the separate subfactors; they are also aligned with both PGI theory and the intended uses of the PGIS-II (Robitschek et al., 2012).

Both the findings of the current study and their implications suggest future directions for research. First, although the findings indicate nuanced relations among the PGI factors and coping, it is unclear how interventions to increase either PGI or specific coping mechanisms might also facilitate the other’s development. As past interventions to increase PGI have primarily been examined in college students (Meyers et al., 2015; Thoen & Robitschek, 2013), adding a focus on coping as an outcome measure might be an important next step in refining such interventions. Additionally, the findings add to the limited literature on PGI and coping by explicating different patterns of relations between PGI and coping; however, more research is needed to investigate how these different patterns predict specific outcomes in college students, such as psychological well-being, vocational identity, and academic persistence. Finally, we sought to answer the call for additional research explicitly examining how the four PGI factors might differentially relate to other constructs (Robitschek et al., 2012; Weigold et al., 2018). Although our findings align with both PGI theory and the bifactor structure of the PGIS-II (Robitschek et al., 2012; Weigold et al., 2018), much more research is needed to investigate the PGI factors in their relations to different constructs to provide a holistic understanding of both PGI and its operationalization.

6 Limitations

The results of the current study should be interpreted considering several limitations. First, although we attempted to increase the representativeness of our sample by recruiting participants from both a large, public university and a small, private college, our findings may not generalize to all college students or types of institutions (e.g., community colleges, HBCUs). Second, participants were self-selected. Since students who completed this (and other) research studies received course or extra credit for participating, they were likely motivated to do well in their classes and/or engage in research. Next, we collected all data using self-report surveys, which resulted in mono-method bias that may have inflated relations across constructs. Additionally, our study was both correlational and cross-sectional, so it is not possible to determine cause-and-effect relations between PGI and coping. Finally, canonical correlation does not allow for the inclusion of covariates or other variables that might explain patterns, such as the personality characteristics of Conscientiousness or Neuroticism. Consequently, future research is needed to both replicate and extend our findings.

7 Conclusion

The current study’s findings show support for the relations between PGI and coping styles, strategies, and self-efficacy in college students such that higher levels of PGI are generally associated positively with problem-focused and social support-oriented coping and negatively with avoidant coping. They also support the existence of different significant combinations of PGI and coping aspects. Together, these findings have implications for those working in college settings to assist students in approaching stressful situations actively and intentionally with effective coping mechanisms.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

Amirkhan, J. H. (1990). A factor analytically derived measure of coping: The coping Strategy Indicator. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(5), 1066–1074. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.1066

Amirkhan, J. H. (1994). Criterion validity of a coping measure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 62(2), 242–261. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6202_6

Arnett, J. J. (2016). College students as emerging adults: The developmental implications of the college context. Emerging Adulthood, 4, 219–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167696815587422

Ayub, N., & Iqbal, S. (2012). The relationship of personal growth initiative, psychological well-being, and psychological distress among adolescents. Journal of Teaching and Education, 1(6), 101–107. http://www.universitypublications.net/jte/0106/pdf/HVD65.pdf.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37(2), 122–147. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.37.2.122

Bouchard, G., Guillemette, A., & Landry-Léger, N. (2004). Situational and dispositional coping: An examination of their relation to personality, cognitive appraisals, and psychological distress. European Journal of Personality, 18(3), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.512

Cai, J., & Lian, R. (2022). Social support and a sense of purpose: The role of personal growth initiative and academic self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 788841. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.788841

Carver, C. S. (n.d.). COPE (complete version). University of Miami Department of Psychology. https://www.psy.miami.edu/faculty/ccarver/copefull.html1

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1994). Situational coping and coping dispositions in a stressful transaction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66(1), 184–195. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.66.1.184

Carver, C. S., Scheier, M. F., & Weintraub, J. K. (1989). Assessing coping strategies: A theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56(2), 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.59.5.1066

Cheng, C., Ying, W., Ebrahimi, O. V., & Wong, K. F. E. (2024). Coping style and mental health amid the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic: A culture-moderated meta-analysis of 44 nations. Health Psychology Review, 18(1), 141–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2023.2175015

Chang, E. C., Yang, H., Li, M., Duan, T., Dai, Y., Yang, J. Z., Zhou, Z., Zheng, X., Morris, L. E., Wu, K., & Chang, O. D. (2018). Personal growth initiative and life satisfaction in Chinese and American students: Some evidence for using resources in the East and being planful in the West. Journal of Well-Being Assessment, 1(1–3), 49–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41543-018-0004-2

Chesney, M. A., Neilands, T. B., Chambers, D. B., Taylor, J. M., & Folkman, S. (2006). A validity and reliability study of the coping self-efficacy scale. British Journal of Health Psychology, 11(3), 421–437. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910705X53155

Chickering, A. W. (1969). Education and identity. Jossey-Bass.

Clark, K. K., Bormann, C. A., Cropanzano, R. S., & James, K. (1995). Validation evidence for three coping measures. Journal of Personality Assessment, 65(3), 434–455. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_5

Cramer, R., Burks, A. C., Golom, F. D., Stroud, C. H., & Graham, J. L. (2017). The Lesbian, Gay, and bisexual identity scale: Factor analytic evidence and associations with health and well-being. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 50(1–2), 71–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2017.1325703

Cunningham, C. A., Cramer, R. J., Cacace, S., Franks, M., & Desmarais, S. L. (2020). The coping self-efficacy scale: Psychometric properties in an outpatient sample of active duty military personnel. Military Psychology, 32(3), 261–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/08995605.2020.1730683

Daoud, J. I. (2017). Multicollinearity and regression analysis. In Journal of Physics: Conference Series (Vol. 949, No. 1, p. 012009). IOP Publishing.

de Freitas, C. P. P., Damásio, B. F., Tobo, P. R., Kamei, H. H., & Koller, S. H. (2016). Systematic review about personal growth initiative. Anales De Psicología, 32(3), 770–782. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.32.3.219101

Delahaij, R., & Van Dam, K. (2017). Coping the acute stress in the military: The influence of coping style, coping self-efficacy and appraisal emotions. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 13–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.021

Fan, X., & Konald, T. R. (2010). Canonical correlation analysis. In G. R. Hancock, & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), The reviewer’s guide to quantitative methods in the social sciences (pp. 29–40). Routledge.

Freire, C., Del Mar Ferradás, M., Valle, Antonio, Núñez, J. C., & Vallego, G. (2016). Profiles of psychological well-being and coping strategies among university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, e1554. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01554

Gregor, M. A., Weigold, I. K., Wolfe, G., Campbell-Halfaker, D., Martin-Fernandez, J., & Del Pino, G., H. V (2021). Positive predictors of career adaptability among diverse community college students. Journal of Career Assessment, 29(1), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/106907272093253

Gustems-Carnicer, J., & Calderón, C. (2013). Coping strategies and psychological well-being among teacher education students. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 28(4), 1127–1140. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-012-0158-x

Hair, J. F. Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Kato, T. (2013). Frequently used coping scales: A meta-analysis. Stress and Health, 31(4), 315–323. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2557

Kim, H. Y. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 38(1), 52–54. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52

Krypel, M. N., & Henderson-King, D. (2010). Stress, coping styles, and optimism: Are they related to meaning of education in students’ lives? Social Psychology of Education: An International Journal, 13(3), 409–424. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-010-9132-0

Malik, N. I., Yasin, G., & Shahzadi, H. (2015). Personal growth initiative and self esteem as predictors of academic achievement among students of technical training institutes. Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences, 35(2), 702–714.

Meloun, M., & Militký, J. (2011). Statistical data analysis: A practical guide. Woodhead Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1533/9780857097200

Meyers, M. C., van Woerkom, M., de Reuver, R. S. M., Bakk, Z., & Oberski, D. L. (2015). Enhancing psychological capital and personal growth initiative: Working on strengths or deficiencies. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(1), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000050

Nicholls, A. R., Polman, R. C. J., Levy, A. R., & Borkoles, E. (2010). The mediating role of coping: A cross-sectional analysis of the relationship between coping self-efficacy and coping effectiveness among athletes. International Journal of Stress Management, 17(3), 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020064

Parent, M. C. (2013). Handling item-level missing data: Simpler is just as good. The Counseling Psychologist, 41(4), 568–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000012445176

Pedrelli, P., Nyer, M., Yeung, A., Zulauf, C., & Wilens, T. (2015). College students: Mental health problems and treatment considerations. Academic Psychiatry, 39(5), 503–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-014-0205-9

Robitschek, C. (1998). Personal growth initiative: The construct and its measure. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 30(4), 183–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.1998.12068941

Robitschek, C., & Cook, S. W. (1999). The influence of personal growth initiative and coping styles on career exploration and vocational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54(1), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1998.1650

Robitschek, C., & Kashubeck, S. (1999). A structural model of parental alcoholism, family functioning, and psychological health: The mediating effects of hardiness and personal growth orientation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 46(2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.46.2.159

Robitschek, C., & Thoen, M. A. (2015). Personal growth and development. In J. C. Wade (Ed.), Positive psychology on the college campus (pp. 219–238). Oxford.

Robitschek, C., Ashton, M. W., Spering, C. C., Geiger, N., Byers, D., Schotts, C., & Thoen, M. A. (2012). Development and psychometric evaluation of the Personal Growth Initiative Scale – II. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 59(2), 274–287. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027310

Rogers, C. R. (1965). On becoming a person. Houghton Mifflin.

Saranjam, R., Forouzanfar, A., & Samavi, A. (2019). Predicting coping self-efficacy based on social support, personal growth, and mindfulness in people with cancer. Journal of Research & Health, 9(4), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.29252/jrh.9.4.363

Shahrour, G., & Dardas, L. A. (2020). Acute stress disorder, coping self-efficacy and subsequent psychological distress among nurses amid COVID-19. Journal of Nursing Management, 28(7), 1686–1695. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13124

Shigemoto, Y., & Robitschek, C. (2021). Coping flexibility and trauma appraisal predict patterns of posttraumatic stress and personal growth initiative in student trauma survivors. International Journal of Stress Management, 28(1), 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000213

Szymanski, D. M., Mikorski, R., & Carretta, R. F. (2017). Heterosexism and LGB positive identity: Roles of coping and personal growth initiative. The Counseling Psychologist, 45(2), 294–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000017697195

Taušová, J., Bender, M., Dimitrova, R., & van de Vijver, F. (2019). The role of perceived cultural distance, personal growth initiative, language proficiencies, and tridimensional acculturation orientations for psychological adjustment among international students. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 69, 11–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2018.11.004

Thoen, M. A., & Robitschek, C. (2013). Intentional growth training: Developing an intervention to increase personal growth initiative. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 5(2), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12001

Velicer, W. F., Prochaska, J. O., Fava, J. L., Normal, G. J., & Redding, C. A. (1998). Smoking cessation and stress management: Applications of the transtheoretical model of behavior change. Homeostatis, 38(5–6), 216–233.

Weigold, I. K., & Robitschek, C. (2011). Agentic personality characteristics and coping: Relation to trait anxiety in college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 81(2), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2011.01094.x

Weigold, I. K., Weigold, A., Russell, E. J., & Drakeford, N. M. (2014). Examination of the psychometric properties of the Personal Growth Initiative Scale–II in African American college students. Assessment, 21(6), 754–764. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191114524019

Weigold, I. K., Weigold, A., Boyle, R. A., Martin-Wagar, C. A., & Antonucci, S. Z. (2018). Factor structure of the Personal Growth Initiative Scale-II: Evidence of a bifactor model. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(2), 259–266. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000254

Weigold, I. K., Weigold, A., Russell, E. J., Wolfe, G. L., Prowell, J. L., & Martin-Wagar, C. A. (2020). Personal growth initiative and mental health: A meta-analysis. Journal of Counseling & Development, 98(4), 376–390. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12340

Weigold, I. K., Weigold, A., Ling, S., & Jang, M. (2021). College as a growth opportunity: Assessing personal growth initiative and self-determination theory. Journal of Happiness Studies, 22(5), 2143–2163. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00312-x

Weigold, A., Weigold, I. K., Ethridge, E. T., & Chong, Y. K. (2023). Translation and validation of the German personal growth Initiative Scale – II. The Counseling Psychologist, 51(7), 906–932. https://doi.org/10.1177/00110000231181310

Yakunina, E. S., Weigold, I. K., & Weigold, A. (2013). Personal growth initiative: Relations with acculturative stress and international student adjustment. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research Practice Consultation, 2(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030888

Funding

No grants, funds, or other support was received.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

The study discussed in the manuscript was approved by the Institutional Review Board of both universities involved in data collection.

Consent to Participate

All participants received a consent form and agreed to participate in the study.

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Weigold, I.K., Weigold, A., Dykema, S.A. et al. Personal Growth Initiative: Relation to Coping Styles, Strategies, and Self-Efficacy. J Happiness Stud 25, 80 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00782-3

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00782-3