Abstract

Purpose in life is a well-established contributor to positive well-being. However, for a more comprehensive understanding of purpose in life, further exploration is needed about the processes implicated in purpose from a cognitive and affective perspective. This scoping review aims to identify the cognitive and/or affective mechanisms (CAMs) correlating with purpose in life and to examine these relationships based on relevant existing literature. Using search terms related to CAMs and purpose in life, we conducted a comprehensive search across five databases (Web of Science, Medline, Pubmed, Scopus, and psycinfo) to identify those examining the relationship between these constructs. Ninety-nine manuscripts were selected for inclusion. Within these studies, 33 CAMs showed predominantly positive and significant associations with purpose in life. Our findings highlighted the cams empirically and theoretically implicated in purpose development, maintenance, and its association to positive wellbeing. We identified several gaps in current research including issues related to suboptimal measurement of purpose in life, and a lack of longitudinal and intervention studies. Overall, this study represents a foundational step in advancing an understanding CAMs implicated in purpose in life. This scoping review usefully informs the development and validation of future purpose in life measures, and the design of interventions aimed at enhancing purpose in life and wellbeing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Purpose in life is widely recognised as a fundamental aspect of psychological well-being and is intimately linked with motivation and meaningful goal engagement (Kashdan & McKnight, 2009; Ryff & Singer, 2008). Research consistently shows that increased purpose in life is associated with an extensive range of benefits such as increased life satisfaction, psychosocial and physiological well-being, and reduced risk of psychological distress and mortality (AshaRani et al., 2022; Kim et al., 2022). Despite its clear importance, researchers have yet to comprehensively explore the cognitive and affective mechanisms (CAMs) linked with purpose in life consequently hindering advancements in this field.

Though the terms are often used interchangeably, emerging literature is recognising purpose in life and meaning in life as different constructs (George & Park, 2016; Martela & Steger, 2016). According to the tripartite view of meaning, purpose in life is the aspect of meaning in life that is specifically associated with the sense of direction and of having valued goals (George & Park, 2016; Martela & Steger, 2016). Consistent with this perspective, McKnight and Kashdan’s (2009) defined purpose in life as a “central, self-organizing life aim that organises and stimulates goals, manages, behaviours, and provides a sense of meaning” (p. 242). As such, purpose in life refers to a dynamic motivational system that informs how and what they engage with in life (Mcknight & Kashdan, 2009). Subsequent theoretical advancements have recognised purpose in life as developmental process, maintained overtime when individuals reflect and build upon momentary feelings of purposefulness (Hill et al., 2023). Through engaging and expanding on aspects of life identified as purposeful, these areas become integral to the person’s identity, reinforcing an enduring sense of purpose over time (Bronk, 2011; Hill et al., 2023). In turn, having a constant sense of purpose in life provides a constant lens to encourage self-preservation and to guide personal development (Kashdan & Goodman, 2023; Lewis, 2020; Mcknight & Kashdan, 2009).

Despite the progressions in purpose in life theory, there remains limited understanding of the particular processes involved in its development, maintenance, and association with wellbeing (Kashdan et al., 2022; Hill et al., 2023; Pfund & Lewis, 2020). These gaps in the understanding of purpose in life have hindered developments of precise measurements and effective interventions targeting this construct (Kashdan et al., 2023; Kazdin, 2007; Park et al., 2019). Kashdan et al., (2022) criticised existing purpose in life measures for being unable to distinguish it from related lower-level constructs that are associated with similar outcomes (e.g., motivation, illusory sense of purpose) and do not capture the complexity and breadth of purpose in life’s influence. Furthermore, while some purpose in life interventions have shown some promise in enhancing well-being, studies are often unclear on how, or if, purpose in life was effectively targeted (Park, et al., 2019; Shin & Steger, 2014). The consequences of these limitations have extended to healthcare settings where assessment and treatments involving purpose in life are heavily influenced by the clinician’s preconceived biases, resulting in inconsistent administration of these interventions and inadequate tracking of therapeutic progress (Lunt, 2004).

Addressing the previously mentioned gaps in theory and practice requires a shift toward a more comprehensive understanding of the processes involved in purpose in life (Bechtel, 2009; Kazdin, 2007). Specifically, examining the CAMs associated with in purpose in life is important, given the inherent link between purpose in life and higher-order thinking, motivation, and emotional reward (Lewis, 2020; Mcknight & Kashdan, 2009). Based on existing purpose in life theory, potentially relevant CAMs may include those as emotional awareness and sensitivity to positive emotions which are likely required for identifying and connecting with momentary sense of purpose (Hill et al., 2023; Mcknight & Kashdan, 2009).

Self-reflection, curiosity, and the focus on self-improvement may be involved in expanding on feelings of purpose (Mcknight & Kashdan, 2009). Additionally, CAMs such as perseverance, emotional regulation, adaptive coping, and self-confidence could contribute to the relationship between purpose in life and positive wellbeing (Bronk, 2011; Kashdan & Goodman, 2023; Hill et al., 2023; Mcknight & Kashdan, 2009; Pfund & Lewis, 2020).

A focused examination on specific CAMS such as those mentioned above, can lead to greater insight about the formation, maintenance, and outcomes of purpose in life, thereby contributing to more effective measures and psychological interventions targeting purpose in life. While previous literature reviews have examined purpose in life with regard to social determinants, health conditions, and intervention outcomes (e.g., AshaRani et al., 2022; Cohen et al., 2016; Park et al., 2019), none have specifically examined purpose in life in relation to CAMs. Therefore, the current scoping review aims to identify the CAMs that correlate with purpose in life and to interpret their potential association with purpose in life based on existing literature.

2 Method

2.1 Procedure

To guide our review process, we followed the methodological framework outlined in the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Tricco et al., 2018; Peters et al., 2020). Due to the explorative nature of our research question, a scoping review was considered the most suitable approach for the current study, as it enabled us to chart a broad span of data, allowing a more inclusive and comprehensive understanding of the relationship between purpose in life and a broad range of CAMs (Peters et al., 2020). The present scoping review protocol was pre-registered with Figshare and Open-Source Framework (Fang, 2023a; Fang, 2023b).

2.2 Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria included studies with: (i) a self-report measure of purpose in life, (ii) a measure of CAMs, and (iii) effect sizes between measures of purpose in life and CAMs. Exclusion criteria included: (i) non-empirical articles (e.g., opinion papers), (ii) studies not available in English, (ii) child and adolescent studies, (iii) qualitative research data, and (iv) review papers.

2.3 Search Strategy

The search strategy aimed to locate both published and unpublished studies. We identified relevant search terms by reviewing MeSh terms, and a preliminary search of abstracts, titles, and keywords of relevant literature. With the intent of being as inclusive as possible, the full search strategy (see Supplementary Materials, Table 1) included the use of Boolean operators and terms to identify articles pertaining to purpose in life (e.g., “life aim”, “life ambition”) and CAMs (e.g., “cognit* process*”. “affect* mechanism*”). The final list of items was reviewed and validated by the research team.

2.4 Information Sources

Search terms were entered into five databases with a psychological focus (Web of science, Medline, Pubmed, Scopus, and PsycInfo). Reference lists of included sources were also examined to identify manuscripts that were not captured in the initial search. No limitations were set based on date or location.

2.5 Evidence Selection

Following the initial searches, all identified papers were collected and imported into EndNote 20 (Clarivate Analytics, 2022). After removing duplicate entries, the first-named author reviewed titles and abstracts to identify manuscripts that potentially met the eligibility criteria and then retrieved full-text versions. The first-named author then examined the full-text manuscripts to confirm they met eligibility criteria. To reduce the risk of error and bias, a random 40% of excluded and included texts were reviewed by two independent researchers (Tricco et al., 2018). The level of agreement with the independent researchers for the assessment of eligibility were 85% and 96%, respectively. All disagreement between the reviewers were resolved through discussion and mutual consensus.

2.6 Data Charting and Items

The descriptive data extracted from papers included the names of the authors, year of publication, country of origin, sample characteristics (sample size, gender distribution, age, recruitment method), research design, measures of purpose in life, and measures of CAMs. Analytic data included the effect sizes of associations between purpose in life and the respective CAMs.

2.7 Critical Appraisal of Evidence

Though not essential for scoping reviews, we assessed the quality of evidence in our study to ensure that the quantitative findings of the included studies are rigorous enough to usefully inform the findings of the current scoping review (Tricco et al., 2018). To achieve this, we merged two critical appraisal tools that have proven useful in previous scoping reviews of psychological constructs and mechanisms (e.g., Xiong et al., 2023), the Critical Appraisal Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies (JBI-CACS) and the Critical Appraisal Checklist for Cohort Studies (JBI-CCS). Our modifications included adapting the instructions, and criteria to suit purpose in life literature (e.g., “was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way” was changed to “was purpose in life measured in a valid and reliable way”).

The adapted JBI critical appraisal tool comprises 11 criteria covering sample size and setting, participant recruitment and description, validity and reliability of measures of purpose in life and CAMs, confounding variables, and suitability of the statistical analysis. For longitudinal studies, additional criteria covered the follow-up period, completion rate, and strategies to address incomplete follow-up. Each criterion was scored with a response format of Yes, No, Unclear, Partial, or Not Applicable. All included studies underwent full appraisal by the primary author with a randomly selected 50% assessed by a second independent reviewer. The level of agreement between reviewers for quality assessment was 88.4%. Discrepancies between the two reviewers were resolved through consensus. No studies were excluded from the current review due to poor critical appraisal outcomes. The final version of the critical appraisal tool can be seen in Supplementary Materials, Table 2.

2.8 Synthesis of Results

We developed a tool that facilitated categorisation of effect sizes based on three levels of increasing specificity to aid synthesis and organisation of CAMs. At the broadest level, CAMs were organised into three categories based on a commonly used framework for contextualising psychological processes: self, world, and other (e.g., Lipkus et al., 1996). CAMs of the self will include processes involved in self-concept and internal experiences. CAMs associated with the world will target mechanisms related to conceptions of the environment and events external to the self. CAMs regarding others are those related to one’s relationship with others. The second level domain describes the outcome or intent associated with the CAMs, while the third, most specific level describes shared characteristics of CAMs themselves.

To chart and synthesise findings across the studies we categorised cross-sectional effect sizes following Gignac and Szodorai’s (2016) guidelines for effect sizes which is specific to research in individual differences. Focusing on at least medium effect sizes (0.20), we aimed to capture relationships with potential for explanatory and significance of findings in the short and long term (Funder & Ozer, 2019). The synthesis of results was reviewed in full by an independent second researcher to ensure accuracy of the data charting process. Due to the scarcity of longitudinal and cohort research examining purpose in life in relation to distinct CAMs (n = 5), we conducted a separate narrative synthesis to examine temporal relationships over time between CAMs and subsequent levels of purpose in life and/or group-effects between groups.

3 Results

3.1 Study Selection

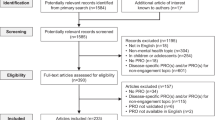

Using the search strategy developed for this scoping review, a total of 3187 research articles were retrieved from Web of Science, Medline, PsycInfo, Pubmed, Scopus in March 2023. After removing duplicates, we screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining 2008 articles based on the eligibility criteria. This led to the exclusion of 1599 papers, leaving 409 articles for full-text screening. Subsequently, an additional 310 manuscripts were eliminated based on the eligibility criteria, resulting in a total of 99 papers for data charting and synthesis. Details of the identification and screening procedure is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram in Fig. 1 below.

3.2 Study Characteristics

Of the 99 papers included in the scoping review, the majority were conducted in the United States which accounted for 56 (57%) papers. Spain followed with eight papers (8%), Poland, with four (4%), and then Australia, Canada, Italy, and the UK which each contributed three papers (3%). China, Japan, the Netherlands, Romania, and Iran each produced two papers (2%). Additionally, nine countries including Switzerland, Belgium, Brazil, Germany, Croatia, Turkey, Portugal, Ecuador, and South Korea produced one (1%) paper each.

Of the 117 samples identified across the included papers, 46 (39%) comprised college and university students, while 45 (38%) samples involved community populations. Twelve samples (10%) comprised hospital patients, and an additional four (3%) samples were recruited from mental health settings or engaged with social services. The remaining 10 samples (9%) included participants from various backgrounds including clergy, pregnant women, office workers, teachers, veterans, nurses, therapists, divorcees, and parents of adolescence.

We found that 73 (62%) of the 117 identified samples consisted of predominantly female participants (i.e., 60% or more of the total sample size) with seven of these (6%) consisting of solely female respondents. Male participants made up the larger proportion in 10 (9%) studies, with three (3%) having an all-male sample group. The remaining 34 (29%) samples comprised a gender distribution between 40 and 60% for both male and female participants. Data from trans and gender-diverse participants were reported in eight (6%) samples, representing between of 0.004 and 3.107% of the sample size in the respective studies. Detailed descriptive characteristics for each individual study included in this review can be seen in Supplementary Materials, Table 3.

3.3 Critical Appraisal

Using our adapted JBI critical appraisal tool, we determined that 83 (84%) of the 99 papers included sufficient information about the sample and setting of the study with details such gender, age, recruitment strategy and the location of the study. Of these, 47 (47%) studies used a standardised criterion to define the intended sample, while 34 (34%) recruited convenience-based community samples. Only 15 (15%) studies accounted for confounding variables within the research design or analysis. Ninety-five (96%) studies included a valid and reliable measure of purpose, and 89 (90%) used valid and reliable measures of relevant CAMs.

Ninety-eight (99%) studies used a cross-sectional, correlational analysis, while one (1%) study assessed differences in CAMs between participants with low, medium, and high levels of purpose in life. Of the correlational studies, only four (4%) also included a longitudinal design to examine the relationship between CAMs and subsequent levels of purpose in life. All four longitudinal studies demonstrated appropriate handling of incomplete data and allowed sufficient time for follow-up, ranging from an average of 3 months to 9 years. However, one study (Pinquart & Fröhlich, 2009) did not control for the influence of baseline levels of purpose in life. Detailed outcomes of the critical appraisal process for the individual studies can be seen in Supplementary Materials, Table 4.

3.4 Synthesis of Measures of Purpose in Life

We identified a total of 20 measures used to assess purpose in life across the 99 studies. The Purpose subscale of Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Wellbeing (PWB-P; Ryff, 1989) was the most frequently used measure of purpose and was reported in 47 (47%) of the 99 studies. The Purpose in Life Test (PILT) was the second most commonly used measure of purpose in life, in a total of 21 (21%) studies. However, it is worth mentioning that the PILT was administered in a range of abbreviated forms including the original 20-item measure (Crumbaugh & Maholick, 1964), Schulenberg et al.’s (2011) 4-item short-form, the 12-item version (Schwartz, 2007; Schwartz et al., 2009), a 2-item version (Schwartz & Finley, 2010), and modified 5-point response scale (Abeyta et al., 2015). Shorter versions of the PILT generally demonstrated psychometric properties comparable or stronger than those reported for the original version.

Scheier et al.’s (2006) Life Engagement Test (LET) was shown to be the third most frequently administered measure and was used in a total of nine studies (9%). Following the LET, Purpose subscale of the Life Aptitude Profile (LAP-P; Reker & Peacock, 1981) and the Multidimensional Measure of Meaning (MMEM; George & Park, 2017) were each administered in three (3%) studies. The Purpose Subscale of the Positive Psychological Functioning Scale (PUFF-P; Merino & Privado, 2015) and the Brief Purpose in Life Scale (BPIL; Hill et al., 2016b) were each used in two papers (2%). The remaining 12 measures of purpose in life were each administered once (1%) across the included studies. A brief description of the five most frequently used measures of purpose are presented in Table 1 below.

3.5 Synthesis of Cognitive and Affective Mechanisms (CAMs)

Across all 99 manuscripts, 430 cross-sectional effect sizes were examined to explore the relationship between purpose in life and CAMs. The majority of these associations (n = 257) represented the domain of self, followed by the domain of the world (n = 154), and the fewest in the domain of other (n = 41). A total of 291 measures of CAMs were consolidated into 73 distinct categories (e.g., Agency, Flexible thinking, Compassion for others). For the current review, we focussed on the 33 CAMs that demonstrated at least two significant, positive associations with purpose in life.

3.5.1 Cognitive and Affective Mechanisms (CAMs) Associated with Self

In the domain of self, we identified a total of 34 CAMs of which 15 exhibited predominantly positive associations with purpose in life with at least medium-sized effect. A summary of these associations are shown in Table 2.

As presented in Table 2, CAMs that indicate a stronger sense of identity and self, including self-worth, and self-compassion, self-congruence, grandiosity, and self-transcendence consistently showed strong positive relationships with purpose in life. Additionally, an increased self-perceived autonomy, self-control, agency/self-efficacy also exhibited medium to large positive associations in more than half the respective relationships with purpose in life.

Table 2 also showed positive relationships between purpose in life and creativity and openness, curiosity, attending to thoughts and emotions, and savouring positive affect. However, CAMs that reflected difficulties engaging with positive affect and surrendering to negative thoughts and emotions lacked any significant associations with purpose in life.

Self-perceived cognitive ability showed predominantly positive associations with purpose in life, with at least medium effect sizes. However, this was not the case for actual cognitive ability which was not significantly associated with purpose in life. Furthermore, focusing on self-development, emotional stability, and religiosity/spirituality all showed significant, positive, medium to large effect sizes with purpose in life.

3.5.2 Cognitive and Affective Mechanisms (CAMs) Associated with the World

The world domain comprised a total of 29 CAMs. Eleven of these showed significant associations with purpose in life. Table 3 provides an overview of all CAMs in the world domain and their relationships with purpose in life.

In Table 3, environmental mastery was the most assessed CAM in the domain of the world (n = 22) exhibiting positive and at least medium-sized associations with purpose in life in the large majority (n = 21, 95%) of papers. CAMs of working through adversity, problem solving and planning, adaptive thinking, and perseverance and tenacity, showed mostly positive associations with purpose. While CAMs associated with coping, such as avoidance, blaming others, acceptance, and religion did not show any significant positive associations with purpose in life.

Positive appraisal tendencies demonstrated strong associations with purpose in most of the identified studies, while negative appraisal tendencies did not show significant positive associations with purpose in life. Among the CAMs associated with meaning making, only turning to religion/spirituality and critical reflection and existential thinking showed predominantly positive links with purpose in life of at least medium-sized effects. Additionally, CAMs that indicate clarity of the past, mindfulness of the present, and an orientation, planning and hopefulness for the future exhibited positive associations with purpose. Although contentment showed one large positive effect size with purpose in life (Huang, 1999), this mechanism was not included in the current review due to lack of research in this area.

3.5.3 Cognitive and Affective Mechanisms Associated with the Other

We identified 11 CAMs in the other domain, of which seven showed significant associations with purpose. A summary of these CAMs and the relationships with purpose in life are presented in Table 4.

As seen in Table 4, CAMs that reflect greater connectedness, socialisation, and relational safety and security in others showed positive medium to large effects with purpose in life. Specifically, compassion for others, perceiving shared experiences, extraversion and sociability, social confidence, trusting others, and perceiving support and care from others were each linked to a higher level of purpose.

Regarding the CAMs related to managing status and power in relationships, we found that self-enhancement was significantly and positively associated with purpose in life, while no significant relationships were identified with entitlement. The CAMs indicating difficulties with socialising, mistrust/insecurity, and disconnection from others did not show any significant positive associations with purpose in life.

3.5.4 Longitudinal and Group Comparison Effects

In contrast to cross-sectional studies, the availability of longitudinal and group comparison research was lacking, with only four longitudinal studies and only one group comparison study. The longitudinal studies showed that increased wisdom, subjective memory, and internal locus of control were all better predictors of higher purpose in life rather than outcomes of purpose in life (Ardelt, 2016; Dewitte et al., 2021; Pinquart & Fröhlich, 2009). Additionally, stronger associations were observed between increased purpose in life and higher subsequent levels of grit and optimism compared to when these relationships are temporally reversed (Hill et al., 2016a; Pinquart & Fröhlich, 2009).

The one group comparison study (Chen et al., 2019) found that compared to participants categorised into the lowest-level of sense of purpose, participants at the middle-level and highest-level of self-reported purpose in life reported greater capacity for emotional processing and emotional expression.

4 Discussion

This scoping review aimed to clarify the current understanding of purpose in life by identifying potential associations with CAMs. Following a systematic and comprehensive process guided by the PRISMA-ScR (Peters et al., 2020; Tricco et al., 2018), 99 empirical manuscripts met selection criteria. Thirty-three distinct CAMs showed medium to large, positive associations with purpose in life. These associations are discussed below in relation to relevant theoretical literature. For clarity and ease of reference, the proposed relationships between purpose in life and the CAMs have been visually presented in Fig. 2 below.

Theoretical Associations Between Purpose in life and Cognitive and Affective Mechanisms (CAMs). Note. The cognitive and affective mechanisms included in Figure B refer to CAMs identified in the current study that showed a minimum of two associations with purpose in life where more than 50% of associations were at least medium-sized effects. Italicised text represent the domains relevant to the adjacent CAM. Arrows represent potential pathways between constructs. Two cognitive and affective mechanisms (grandiosity, self-enhancement) were omitted from this figure due to the lack of theoretical connection with purpose in life

4.1 Foundations for Promoting Purpose in Life

The scoping review findings support the view that purpose in life is closely tied to the satisfaction of psychological needs (McKnight & Kashdan, 2009; Ryan & Deci, 2000). CAMs related to autonomy and competence (self-perceived autonomy, self-control, environmental mastery, agency/self-efficacy, and positive self-perceived cognitive ability) emerged as some of the most frequently assessed and reliable correlates of purpose in life. Additionally, longitudinal results showed that increased internal locus of control (Pinquart & Fröhlich, 2009) and subjective evaluation of memory (Dewitte et al., 2021) were positively associated with increased levels of purpose in life over time. This aligns with perspectives that personal freedom and agency contributes to increased purpose in life (Mcknight & Kashdan, 2009; Lewis et al., 2020). Notably, cognitive test performance, as an objective measure of cognitive ability, was not associated with purpose, potentially indicating that purpose development relies more on self-perceived competence rather than actual competence.

Regarding the psychological need for relatedness, our review showed that CAMs of perceived support and care from others, and relational trust and stability consistently demonstrated positive associations with purpose in life. (Deci & Ryan, 2000; Kashdan & McKnight, 2009). These findings support attachment-orientated theories of purpose, emphasising the importance of secure relationships in providing individuals with the confidence to pursue meaningful life directions (Mikulincer & Shaver, 2016). Thus, across the studies examined for the relationship between purpose and CAMs related to psychological needs, those that promote needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness were identified as key mechanisms that support the development of purpose in life.

4.2 The Development of Purpose in Life

Although psychological needs play an essential role in establishing purpose in life, we argue that these factors alone are insufficient to promote and sustain purpose overtime. To discuss the present findings, we use Kashdan and Mcknight’s (2009) proposed pathways of purpose development (proactive development, reactive development, and social learning) to organise the current (see Kashdan & Mcknight, 2009 for further information regarding each pathway).

4.2.1 Proactive Development

We found seven mechanisms of purpose related to Proactive development (the deliberate searching and refining of life’s purpose; Kashdan & Mcknight, 2009). Proactive development contributes to purpose formation when a momentary experience of reward is nurtured into an enduring sense of meaning. According to Kashdan and Mcknight (2009), this process is fuelled by curiosity and active engagement with positive experiences, thus aligning with our findings showing positive and significant relationships between two CAMs identified in the current study, openness and curiosity and savouring positive affect.

When people acknowledge and engage with their meaningful experiences, there is an opportunity for them to use higher-order cognitive processes that allows for a deeper consideration of how the experience can inform their life direction (Kashdan & Mcknight, 2009; Pfund & Lewis, 2020). Accordingly, our findings revealed consistent, positive correlations between purpose and four CAMs of higher-order processing, including attention to thoughts and emotions, critical reflection and existential thinking, future focused orientation and planning, and a focus on self-development. The longitudinal analysis further supports the role of higher-order processing in purpose development, with increased wisdom emerging as a better predictor compared to outcome of purpose in life (Ardelt et al., 2016). The significant relationship between purpose in life and turning to religion/spirituality demonstrates how entwining positive experiences with meaning frameworks can promote a greater sense of purpose (Kashdan & Mcknight, 2009).

4.2.2 Reactive Development

Reactive development (the rapid formation of purpose in response to significant life events; Kashdan & McKnight, 2009) has received less theoretical attention in the literature compared to other pathways of purpose development. Research on posttraumatic growth and transformative learning, where certain CAMs are crucial in revising existential perspectives following significant events, however, highlight the importance of reactive development (Mezirow, 2009; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004). In this scoping review we found two CAMs, remembering the past with clarity and using adaptive approaches when dealing with adversity, were related to increased purpose in life. That is, having the ability to perceive memories easily, vividly, and with clear understanding of the relevant event enables richer access to potentially meaningful experiences (Sutin et al., 2021). Subsequently, adaptive thinking can be used to incorporate this new information into pre-existing purpose in life frameworks (Mezirow, 2009).

4.2.3 Social Learning

Social learning entails the co-construction of purpose in life through observing and connecting with the experiences of others (Kashdan & Mcknight, 2009). This pathway is supported in literature emphasising the role of social observations and engagement in the formation of identity and meaning-making frameworks (Bandura, 1969; Kashdan & McKnight, 2009). Just as the viewpoints and habits of a person can be unconsciously adopted among close friends, purpose in life can also be transmitted between people, often without conscious effort or explicit recognition (Bandura, 1969; Kashdan & McKnight, 2009).

We identified two CAMs positively correlated with purpose in life and linked to the process of developing purpose through social learning. The first CAM is perceiving shared experiences with others, which underscores the collaborative nature of promoting purpose through social learning (Kashdan & Mcknight, 2009; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2005; Pittman et al., 2011). The second CAM, compassion for others, reflects a sensitivity and commitment to alleviating distress of others (Gilbert et al., 2017). This inclination toward compassion for others facilitates the identification of life directions that address self-transcendent needs (Damon et al., 2003). The connection between purpose in life and these relational-focused CAMs is an important consideration, as theories often overlook the significance of sharing experiences and addressing social needs in purpose development. However, it is important to note that a purpose in life does not necessarily have to supersede self-interest; instead, it can be considered that the needs of self are integrated with the needs of others (Malin et al., 2014).

Overall, Kashdan and Mcknight’s (2009) framework of the three pathways to purpose effectively contextualises the CAMs identified in this review as potential contributors to increased purpose in life. However, it is worth noting that some CAMs identified in this review are more theoretically aligned with the benefits of purpose, as discussed below.

4.3 The Outcomes of Purpose in Life

The strong connection between purpose in life and a vast range of wellbeing benefits can be attributed to its role as a comprehensive, ubiquitous framework that guides people in their understanding and engagements with themselves, others, and the world (Bronk, 2011; Mcknight & Kashdan, 2009; Pfund & Lewis, 2020; Ryff & Singer, 2008). Purpose can serve as a constant target for people to pursue and hone throughout their lives. Its stability over time and across contexts enables it to function as an anchor that supports people’s self-regulation and perseverance in pursuit of meaningful life engagements (Kashdan & Goodman, 2023; Lewis, 2020; Pfund et al., 2020).

Consistent with well established relationships between purpose and wellbeing, our review showed significant associations between purpose in life and a range CAMs that signify positive psychological outcomes. These mechanisms include those that reflect a positive sense of self and identity (self-congruence, self-transcendence, self-worth and self-compassion), resilience (perseverance and tenacity), self-regulation (emotional stability, religiosity/spirituality), positive perceptions of the world (positive appraisal/biases, mindfulness, hopefulness), greater fulfilment from social engagement (social confidence, extraversion/sociability), self-expression and innovation (creativity) and a proactive approach to managing adversity (problem solving, planning, and focussing on the task).

4.4 A Flexible Model for Conceptualising Purpose

By applying relevant theories to the scoping review findings, useful insights are gained into the potential connections between purpose in life and the specific CAMs identified in this review. However, considering the complex conceptual relationships between constructs and scarce availability of longitudinal and intervention data, it is highly likely that the relationship between purpose and the respective CAMs are more dynamic than previously investigated or proposed in the literature. For example, the relationship between purpose and certain CAMs may be bidirectional (e.g., purpose may promote creativity and, in turn, creativity may promote purpose), moderated (e.g., the relationship between purpose in life and religiosity/spirituality may depend on a history of meaning-making by turning to religion/spirituality) or mediated by other CAMs (e.g., savouring positive affect may mediate the relationship between remembering past events with clarity and purpose in life). Hence, our interpretation of the current findings should be regarded as a preliminary representation of the current empirical and theoretical state of purpose in life literature, which is subject to continuous testing, adaptation, and refinement.

4.5 Limitations, Gaps, and Future Directions

While a scoping review methodology was the most appropriate approach for addressing the aims of the current review, inherent limitations exist (Tricco et al., 2018). For instance, the broad scope of our review necessitated the use of more generalised search terms, which, due to word limit constraints of our chosen engines, might have resulted in the omission of relevant articles. Further, given developmental differences in purpose in life across the lifespan our focus on adult samples means that our findings are not generalisable to child and adolescent populations.

The lack of longitudinal and group comparison studies hinders an ability to identify more complex and dynamic interactions between purpose in life and the relevant CAMs. Most studies were conducted in the United States (57%), and with university populations (39%), which somewhat limits the generalisability of the findings to other populations and other countries.

The scoping review identified a significant reliance on a limited number of purpose in life measures, with 77% of the papers included in this review using one of three main measures used to assess purpose in life (i.e., the PWB-P, PILT, and LET). Limitations have been raised by authors regarding the factor structure (Kafka & Kozma, 2002; Schulenberget al., 2011) and validity (Kashdan et al., 2022) of these measures. Consequently, this has led to difficulties in differentiating between purpose in life and related but conceptually distinct constructs (e.g., obligation, social pressures, and over compensatory strategies; Isham et al., 2022; Kashdan & Mcknight, 2009; Tracy et al., 2009). Notably, it seems that self-reported purpose in life was positively linked to two CAMs (i.e., grandiosity, self-enhancement) that tap into a form of psychopathology (narcissism). Because these two CAMs were inconsistent with contemporary theory of purpose in life and not the focus of the current scoping review aim, they were not included in scoping review analysis.

Based on the limited longitudinal and comparative research identified by the current review, future studies should examine the temporal, comparative, interactive, and causal relationships between the specific CAMs identified and purpose in life. This is likely to provide a deeper understanding of these associations in the context of contemporary purpose theory.

For CAMs that were less frequently assessed (e.g., self-transcendence, creativity, perceiving support, and care from others), we also propose conducting more correlational studies across diverse demographics to further test the strength of their relationship with purpose in life. Moreover, we encourage more in-depth meta-analytical investigations into the CAMs that reliably demonstrate strong, positive associations with purpose in life (e.g., autonomy, environmental mastery, self-worth and self-compassion, openness and curiosity, positive reappraisal tendencies) and the potential confounding variables influencing these relationships.

Finally, our findings support the need to integrate purpose-related CAMs in the development of theoretically informed, empirically validated measures of purpose in life. To achieve this, future measures should design items that assess the ongoing processes individuals use to maintain the sense of life purpose over time (e.g., I often reflect upon my direction in life), rather than simply quantifying the extent of purpose experienced in a specific moment (e.g., I feel that I my life is purposeful). Additionally, we observed limited focus of the emotional aspect of purpose in life in existing measures and anticipate that consideration of the more affective mechanisms identified in the current study (e.g., openness and curiosity, savouring positive affect) in future measures will contribute to more theoretically consistent and robust measures to understand and assess purpose in life.

5 Conclusions

Purpose in life has long been recognised as a significant contributor to subjective-wellbeing and meaning in life (Martela & Steger, 2016; Ryff & Singer, 2008). The current scoping review provides a useful synthesis of CAMs that demonstrate medium to large positive effects in relation to purpose in life. Despite growing interest in purpose in life and its potential benefits, the current scoping review highlights the limitations associated with past related research, which has hindered developments in the theory and the practice of purpose in life.

While existing theory allows us to examine the potential nature of these relationships (i.e., as a foundation for purpose, as part of the process of development of purpose, or as an outcome of purpose), limited measurement of purpose in life and the scarcity of research into the temporal and causal relationships between purpose and the respective CAMs hinders an ability to fully explain or validate these relationships. Nevertheless, our review importantly sheds light on the disparity between theoretical and empirical literature on purpose in life. By illuminating the associations between purpose in life and specific CAMs, the review provides a valuable platform and direction for future research which would benefit from the ongoing development and validation of measures to assess purpose in life, the use of more robust research designs such as longitudinal and experimental research. The identification of key CAMs implicated in purpose in life over time will further inform the nature of purpose in life and potentially lead to the development of more effective pathways towards cultivating purpose in life.

References

Abeyta, A. A., Routledge, C., Juhl, J., & Robinson, M. D. (2015). Finding meaning through emotional understanding: Emotional clarity predicts meaning in life and adjustment to existential threat. Motivation and Emotion, 39(6), 973–983. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-015-9500-3

Ardelt, M. (2016). Disentangling the relations between wisdom and different types of well-being in old age: Findings from a short-term longitudinal study. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(5), 1963–1984. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9680-2

AshaRani, P. V., Lai, D., Koh, J., & Subramaniam, M. (2022). Purpose in life in older adults: A systematic review on conceptualization, measures, and determinants. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19105860

Bandura, A. (1969). Social-learning theory of identificatory process. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.), Handbook of socialization theory and research (pp. 213–261). Rand McNally & Company.

Bechtel, W. (2009). Looking down, around, and up: Mechanistic explanation in psychology. Philosophical Psychology, 22(5), 543–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515080903238948

Bronk, K. C. (2011). The role of purpose in life in healthy identity formation: A grounded model. New Directions in Youth Development, 132, 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/yd.426

Chen, Y., Kim, E. S., Koh, H. K., Frazier, A. L., & Vanderweele, T. J. (2019). Sense of mission and subsequent health and well-being among young adults: An outcome-wide analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 188(4), 664–673. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwz009

Clarivate Analytics (2022). Endnote (20) [computer software]. https://endnote.com

Cohen, R., Bavishi, C., & Rozanski, A. (2016). Purpose in life and its relationship to all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: A meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 78(2), 122–133. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000274

Crumbaugh, J. C., & Maholick, L. T. (1964). An experimental study in existentialism: The psychometric approach to Frankl’s concept of noogenic neurosis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20(2), 200–207.

Damon, W., Menon, J., & Bronk, K. C. (2003). The development of purpose during adolescence. Applied Developmental Science, 7(3), 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0703

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11(4), 227–268.

Dewitte, L., Lewis, N. A., Payne, B. R., Turiano, N. A., & Hill, P. L. (2021). Cross-lagged relationships between sense of purpose in life, memory performance, and subjective memory beliefs in adulthood over a 9-year interval. Aging and Mental Health, 25(11), 2018–2027. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1822284

Fang, L. (2023a). Scoping review protocol: purpose in life and its cognitive and affective mechanisms. https://osf.io/fwmqz

Fang, L. (2023b). Scoping review protocol: Purpose in life and its cognitive and affective mechanisms. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22044614

Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919847202

George, L. S., & Park, C. L. (2017). The multidimensional existential meaning scale: A tripartite approach to measuring meaning in life. Journal of Positive Psychology, 12(6), 613–627. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2016.1209546

George, L., & Park, C. (2016). Meaning in life as comprehension purpose and mattering: Toward integration and new research questions. Review of General Psychology, 20(3), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000077

Gignac, G. E., & Szodorai, E. T. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069

Gilbert, P., Catarino, F., Duarte, C., Matos, M., Kolts, R., Stubbs, J., Ceresatto, L., Duarte, J., Pinto-Gouveia, J., & Basran, J. (2017). The development of compassionate engagement and action scales for self and others. Journal of Compassionate Health Care, 4(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40639-017-0033-3

Hill, P. L., Burrow, A. L., & Bronk, K. C. (2016a). Persevering with positivity and purpose: An examination of purpose commitment and positive affect as predictors of grit. Journal of Happiness Studies, 17(1), 257–269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9593-5

Hill, P. L., Edmonds, G. W., Peterson, M., & Andrews, J. A. (2016b). Purpose in life in emerging adulthood: Development and validation of a new Brief measure. Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(3), 237–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1048817.Purpose

Hill, P. L., Pfund, G. N., & Allemand, M. (2023). The PATHS to purpose: A new framework toward understanding purpose development. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 32(2), 105–110. https://doi.org/10.1177/09637214221128019

Huang, B. H. (1999). Exploring oriental wisdom: Self-transcendence and psychological well-being of adulthood in taiwan. InproQuest dissertations & theses global; proQuest one academic (Issue 304540136). https://www.proquest.com/dissertationstheses/exploring-oriental-wisdom-self-transcendence/docview/304540136/se-2

Isham, L., Sheng Loe, B., Hicks, A., Wilson, N., Bird, J. C., Bentall, R. P., & Freeman, D. (2022). The meaning in grandiose delusions: Measure development and cohort studies in clinical psychosis and non-clinical general population groups in the UK and Ireland. The Lancet Psychiatry, 9(10), 792–803. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(22)00236-X

Kafka, G. J., & Kozma, A. (2002). The construct validity of Ryff’s Scales of Psychological Well-Being (SPWB) and their relationship to measures of subjective well-being. Social Indicators Research, 57(2), 171–190. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014451725204

Kashdan, T. B., Goodman, F. R., McKnight, P. E., Brown, B., & Rum, R. (2023). Purpose in life: A resolution on the definition, conceptual model, and optimal measurement. American Psychologist, Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0001223

Kashdan, T. B., & McKnight, P. E. (2009). Origins of purpose in life: Refining our understanding of a life well lived. Psychological Topics, 18(2), 303–316.

Kashdan, T. B., McKnight, P. E., & Goodman, F. R. (2022). Evolving positive psychology: A blueprint for advancing the study f purpose in life, psychological strengths, and resilience. Journal of Positive Psychology, 17(2), 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.2016906

Kazdin, A. E. (2007). Mediators and mechanisms of change in psychotherapy research. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 3, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091432

Kim, E. S., Chen, Y., Nakamura, J. S., Ryff, C. D., & VanderWeele, T. J. (2022). Sense of purpose in life and subsequent physical, behavioral, and psychosocial health: An outcome-wide approach. American Journal of Health Promotion, 36(1), 137–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/08901171211038545

Lewis, N. A. (2020). Purpose in life as a guiding framework for goal engagement and motivation. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 14(10), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12567

Lipkus, I. M., Dalbert, C., & Siegler, I. C. (1996). The importance of distinguishing the belief in a just world for self-versus for others: Implications for psychological wellbeing. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 22(7), 666–677. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167296227002

Lunt, A. (2004). The implications for the clinician of adopting a recovery model: The role of choice in assertive treatment. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 28(1), 93–97. https://doi.org/10.2975/28.2004.93.97

Malin, H., Reilly, T. S., Quinn, B., & Moran, S. (2014). Adolescent purpose development: Exploring empathy, discovering roles, shifting priorities, and creating pathways. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 24(1), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12051

Martela, F., & Steger, M. F. (2016). The three meanings of meaning in life: Distinguishing coherence, purpose, and significance. Journal of Positive Psychology, 11(5), 531–545. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2015.1137623

McKnight, P. E., & Kashdan, T. B. (2009). Purpose in life as a system that creates and sustains health and well-being: An integrative, testable theory. Review of General Psychology, 13(3), 242–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017152

Merino, M.-D., & Privado, J. (2015). Positive psychological functioning. Evidence for a new construct and its measurement. Anales de Psicología, 31(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.31.1.171081

Mezirow, J. (2009). An overview of transformative leaning. In Contemporary theories of learning: Learning theorists in their own words (pp. 90–105). Routledge.

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2005). Attachment security, compassion, and altruism. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14(1), 34–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00330.x

Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2016). Attachment orientations and meaning in life. In J. A. Hicks & C. Routledge (Eds.), The experience of meaning in life: Classical perspectives, emerging themes, and controversies (pp. 1–417). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6527-6

Park, C. L., Pustejovsky, J. E., Trevino, K., Sherman, A. C., Esposito, C., Berendsen, M., & Salsman, J. M. (2019). Effects of psychosocial interventions on meaning and purpose in adults with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer, 125(14), 2383–2393. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32078

Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. https://doi.org/10.11124/JBIES-20-00167

Pfund, G. N., & Lewis, N. A. (2020). Aging with purpose: Developmental changes and benefits of purpose in life throughout the lifespan. In P. L. Hill & M. Allemand (Eds.), Personality and healthy aging in adulthood: New directions and techniques (pp. 27–42). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-32053-9_3

Pfund, G. N., Edmonds, G. W., & Hill, P. L. (2020). Associations between trauma during adolescence and sense of purpose in middle-to-late adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(5), 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419896864

Pinquart, M., & Fröhlich, C. (2009). Psychosocial resources and subjective well-being of cancer patients. Psychology and Health, 24(4), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440701717009

Pittman, J. F., Keiley, M. K., Kerpelman, J. L., & Vaughn, B. E. (2011). Attachment, identity, and intimacy: Parallels between Bowlby’s and Erikson’s paradigms. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 3(1), 32–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-2589.2010.00079.x

Reker, G. T., & Peacock, E. J. (1981). The life attitude profile (LAP): A multidimensional instrument for assessing attitudes toward life. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0081178

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 67–78.

Ryff, C. D. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(6), 1069–1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0

Scheier, M. F., Wrosch, C., Baum, A., Cohen, S., Martire, L. M., Matthews, K. A., Schulz, R., & Zdaniuk, B. (2006). The life engagement test: Assessing purpose in life. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 29(3), 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-005-9044-1

Schulenberg, S. E., Schnetzer, L. W., & Buchanan, E. M. (2011). The purpose in life test-short form: Development and psychometric support. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(5), 861–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-010-9231-9

Schwartz, S. J. (2007). The structure of identity consolidation: Multiple correlated constructs or one superordinate construct? Identity, 7(1), 27–49. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283480701319583

Schwartz, S., & Finley, G. (2010). Troubled ruminations about parents: Conceptualization and validation with emerging adults. Journal of Counseling and Development, 88(1), 80–91. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2010.tb00154.x

Schwartz, S. J., Zamboanga, B. L., Weisskirch, R. S., & Rodriguez, L. (2009). The relationships of personal and ethnic identity exploration to indices of adaptive and maladaptive psychosocial functioning. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 33(2), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025408098018

Shin, J. Y., & Steger, M. F. (2014). Promoting meaning and purpose in life. In A. C. Parks & S. M. Schueller (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of positive psychological interventions (pp. 90–110). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118315927.ch5

Sutin, A. R., Luchetti, M., Aschwanden, D., Stephan, Y., & Terracciano, A. (2021). Sense of purpose in life, cognitive function, and the phenomenology of autobiographical memory. Memory, 29(9), 1126–1135. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658211.2021.1966472

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: A new perspective on psychotraumatology. Psychiatric Times, 21(4), 8–14. https://www.psychiatrictimes.com/view/posttraumatic-growth-new-perspective-psychotraumatology

Tracy, J. L., Cheng, J. T., Robins, R. W., & Trzesniewski, K. H. (2009). Authentic and hubristic pride: The affective core of self-esteem and narcissism. Self and Identity, 8(2–3), 196–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860802505053

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., & Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Xiong, T., Milios, A., McGrath, P. J., & Kaltenbach, E. (2023). The influence of social support on posttraumatic stress symptoms among children and adolescents: a scoping review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.2011601

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Abraham Kenin and Kathryn Morgan-Smith the independent reviewers who assisted with article selection and quality assessment for this project.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions. The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or the publication of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical Approval

Ethics approval for this project was granted by the Edith Cowan University Human Research Ethics Committee (REMS reference number: 2022-03883-FANG).

Informed Consent

The scoping review was based on ethically approved individual published articles and consent was provided in the individual studies conducted.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Fang, L., Allan, A. & Dickson, J.M. Purpose in Life and Associated Cognitive and Affective Mechanisms. J Happiness Stud 25, 63 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00771-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00771-6