Abstract

This study examined whether self-compassion at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic predicted higher subjective well-being and lower psychopathological symptoms through more functional and less dysfunctional coping. Among 430 adults, self-compassion, coping, life satisfaction, positive and negative affect, and depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms were assessed longitudinally over 6 weeks (from 04/2020 to 07/2020). Structural equation modeling revealed that self-compassion at T1 predicted more functional and less dysfunctional coping at T2 (controlling for coping at T1) and more positive and less negative affect and lower stress symptoms at T3 (controlling for these measures at T1). More functional and less dysfunctional coping at T2 (controlling for coping at T1) predicted higher subjective well-being and lower psychopathological symptoms at T3 (controlling for these measures at T1), with the sole exception that functional coping was not significantly associated with anxiety symptoms. In addition, we found that less dysfunctional coping mediated (a) nearly one-third (30.77%) of the association between higher self-compassion and less negative affect and (b) nearly half (46.15%) of the association between higher self-compassion and lower stress symptoms. These findings support the idea that a self-compassionate attitude prevents dysfunctional thoughts (e.g., self-blame) and behaviors (e.g., substance use) during stressful times, which in turn reduces negative affect and symptoms of stress.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has been associated with various stressors (e.g., fear and uncertainty, illness, social isolation, or job insecurity), lower subjective well-being, and higher psychopathological symptoms (e.g., depression, anxiety, and stress) (Robinson et al., 2022; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020; Wu et al., 2021). Understanding how these well-being impairments unfold is essential to improving early intervention approaches.

A highly relevant construct in the field of subjective well-being is self-compassion (Neff, 2003a, 2003b). Self-compassionate individuals comfort themselves with emotional warmth, a sense of connectedness, and balanced awareness during stressful times. Consistently, higher self-compassion has been associated with higher life satisfaction, more positive and less negative affect, lower symptoms of anxiety, depression, and stress, and a lower risk of mental disorders (MacBeth & Gumley, 2012; Marsh et al., 2018; Muris & Petrocchi, 2017; Zessin et al., 2015).

One possible explanation for these associations is that self-compassionate individuals may cope more successfully with stress (Ewert et al., 2021). As suggested by Lazarus’ transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), stress-related impairments in subjective well-being result not only from environmental stressors, but also from the way individuals appraise and respond to them. For example, negative experiences may lead to much higher levels of perceived stress if they are interpreted as overwhelming and uncontrollable rather than manageable. According to Neff (2003b), self-compassion facilitates an open and accepting attitude toward one’s own shortcomings, which enables one to process challenges more constructively and thus buffers feelings of stress. Taken together, it is theoretically plausible to assume that higher self-compassion promotes functional coping and thus fosters subjective well-being in challenging times (e.g., during the pandemic).

Consistent with this idea, higher self-compassion has been associated with more functional (e.g., emotional support, instrumental support, planning, positive reframing, and acceptance) and less dysfunctional (e.g., denial, self-blame, behavioral disengagement, and substance use) coping (Ewert et al., 2021), which in turn has been linked to higher subjective well-being (Ewert & Schröder-Abé, 2022). Moreover, some findings suggest that the beneficial effects of self-compassion on subjective well-being may be mediated by more adaptive and less maladaptive coping (Diedrich et al., 2017; Ewert & Schröder-Abé, 2022; Ewert et al., 2018, 2023; Homan & Sirois, 2017; Krieger et al., 2016; Sirois et al., 2015). For example, the association of momentary self-compassion with more positive and less negative affect has been shown to be due in part to higher engagement and lower disengagement (Ewert & Schröder-Abé, 2022).

The current study aims to replicate and extend these findings by focusing on associations between self-compassion, coping, and subjective well-being and psychopathological symptoms over 6 weeks at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our hypotheses (preregistered at https://osf.io/n7asw/?view_only=6a8af66e849e44c59987ff71b237aff4) are as follows: Higher self-compassion and more functional and less dysfunctional coping predict higher subjective well-being and lower psychopathological symptoms. Higher self-compassion predicts more functional and less dysfunctional coping. The beneficial effects of self-compassion on subjective well-being and psychopathological symptoms are mediated by more functional and less dysfunctional coping. Life satisfaction is used as an indicator of cognitive well-being, positive and negative affect are used as indicators of affective well-being, and depression, anxiety, and stress are used as indicators of psychopathological symptoms.

In most research, self-compassion is conceptualized and measured with 6 paired subscales (Neff, 2003a). Each pair consists of a positive (i.e., compassionate) and a negative (i.e., uncompassionate) scale: self-kindness vs. self-judgement, common humanity vs. self-isolation, and mindfulness vs. over-identification. The uncompassionate scales (self-judgement, self-isolation, and over-identification) are reverse-coded, so that higher levels on each scale reflect higher levels of self-compassion.

2 Materials and Methods

2.1 Study Design

A 6-week longitudinal online survey with 3 waves (T1-T3) was conducted among 435 adults from Germany during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic (i.e., from April 2020 to July 2020). Participants were recruited via social media (e.g., Facebook) and participant pools at the University of Potsdam and the University of Greifswald, Germany. After registration, participants received an email with a link to the study. They were invited to T2 2 weeks after T1 and to T3 4 weeks after T2. Self-report measures on self-compassion, coping, subjective well-being, and psychopathological symptoms were collected at each wave.

The authors affirm that all procedures contributing to this work meet the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to data collection.

2.2 Sample

In this publication, individuals with any information on self-compassion, coping, and/or subjective well-being / psychopathological symptoms at T1 were included (N = 430). That is, 5 individuals without T1 information on these measures were excluded. At T1, 360 individuals self-identified as female, 65 individuals self-identified as male, and 5 individuals self-identified as diverse. Participants ranged in age from 18 to 76 years (M = 31.46, SD = 11.59 years) and were primarily students (N = 206) or other-employed (N = 135). 26 individuals were self-employed, 15 individuals were unemployed, 11 individuals were retired, and 37 individuals reported other occupational status (e.g., maternity leave). Twenty-one individuals were married and 409 individuals were unmarried. 414 individuals currently resided in Germany, 4 in Switzerland, 4 in Austria, and 8 in other countries. 9, 12, and 14 individuals reported that they had (ever) tested positive for COVID-19 at T1, T2, and T3, respectively.

2.3 Attrition

Of the total sample (N = 430), 317 individuals provided information on self-compassion, coping, and/or subjective well-being / psychopathological symptoms at T2, and 264 individuals provided information on any of these measures at T3. Age, gender, nationality, and prior COVID-19 infection did not differ significantly between those who participated and those who did not participate until T3 (all p-values > 0.05). Significantly more students (N = 144, 69.9%) vs. non-students (N = 120, 53.6%) and unmarried (N = 258, 63.1%) vs. married (N = 6, 28.6%) individuals participated until T3.

2.4 Assessment of Self-compassion

Three positive subscales (self-kindness, common humanity, and mindfulness) and 3 negative subscales (self-judgement, self-isolation, and over-identification) were assessed using the German version of the 26-item Self-Compassion Scale (Hupfeld & Ruffieux, 2011; Neff, 2003a). Example items are “I try to be understanding and patient towards those aspects of my personality I don’t like.” (self-kindness), “I am disapproving and judgmental about my flaws and inadequacies.” (self-judgement), “I try to see my failings as part of the human condition.” (common humanity), “I think that other people are happier than I am.” (Self-isolation), “I try to take a balanced view of the situation.” (mindfulness), and “I get carried away with my feelings.” (over-identification), rated from 1 = "not at all" to 5 = "very much". Negative subscales were reverse-scored so that higher scores indicate higher self-compassion (i.e., lower self-judgement, lower self-isolation, and lower over-identification, respectively). In this study, internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) at T1 was 0.93 for the total self-compassion score.

2.5 Assessment of Coping

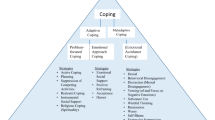

Functional coping (active coping, emotional support, instrumental support, planning, positive reframing, and acceptance) and dysfunctional coping (denial, self-blame, behavioral disengagement, and substance use) were assessed using the German version of the Brief COPE inventory (Carver, 1997; Knoll et al., 2005), which consists of 28 items asking respondents how they typically dealt with past stressful situations, rated from 1 = “not at all” to 4 = “very much”. Example items are “I’ve been concentrating my efforts on doing something about the situation I’m in.” (Active coping), “I’ve been learning to live with it.” (Acceptance), “I’ve been refusing to believe that it has happened.” (Denial), or “I’ve been giving up the attempt to cope.” (Behavioral disengagement). Cronbach’s alpha at T2 was 0.77 for functional coping and 0.68 for dysfunctional coping.

2.6 Assessment of Subjective Well-being

As an indicator of cognitive well-being, general life satisfaction was assessed using the German version of the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al., 1985; Glaesmer et al., 2011), which asks respondents how much they agree with different statements (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life.”; “My living conditions are excellent.”) on a 7-point Likert scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.91 at T3.

As indicators of affective well-being, levels of positive and negative affect were measured using a German short version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Grühn et al., 2010; Watson & Clark, 1994). This instrument asks respondents to what extent they experienced different affective states in the past 2 weeks on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = “not at all” to 7 = “extremely”. Five items were used to assess positive (i.e., active, stimulated, alert, resolute, and attentive) and negative (i.e., angry, hostile, ashamed, nervous, and anxious) affect, respectively. Cronbach’s alpha at T3 was 0.84 for positive affect and 0.79 for negative affect.

2.7 Assessment of Psychopathological Symptoms

The German version of the 21-item Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995; Nilges & Essau, 2015) was used to measure symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in the past 2 weeks, each with 7 items labeled from 0 = “not at all” to 3 = “strongly / most of the time”. The depression items refer to symptoms of anhedonia and inactivity (e.g., “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feelings at all.”). The anxiety items refer to symptoms of physiological hyperarousal and specific fears (e.g., “I felt scared without any good reason.”). The stress items refer to general stress (e.g., “I found it hard to wind down.”). Cronbach’s alpha at T3 was 0.93 for depression, 0.82 for anxiety, and 0.89 for stress.

2.8 Statistical Analysis

Stata 15 was used for the analyses (StataCorp, 2017). Analyses were preregistered at https://osf.io/n7asw/?view_only=012ab3087cac42c9abc202fd28f75672. The openly accessible analysis scripts are included as supplementary material.

Associations of self-compassion at T1 and coping at T2 (controlling for coping at T1) with subjective well-being and psychopathological symptoms at T3 (controlling for subjective well-being / psychopathological symptoms at T1) and associations of self-compassion at T1 with coping at T2 (controlling for coping at T1) were tested using the structural equation model (SEM) estimation command in Stata. To test the mediation hypotheses, we estimated the indirect effects of self-compassion on subjective well-being and psychopathological symptoms through coping and calculated the proportions of the total effects passing through coping. (In our preregistration, we did not plan to control for baseline levels of coping and/or subjective well-being and psychopathological symptoms at T1. We decided to do so based on the reviewers' comments and thank the reviewers for this suggestion.)

Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to handle missing data. Dimensional variables were standardized based on their means and standard deviations at T1 (M = 0, SD = 1). All analyses were controlled for gender (male vs. female), age, and student/non-student status at T1. The alpha level was set at 0.05.

As suggested by previous research (Fritz & MacKinnon, 2007), 462 cases are needed to detect indirect effects when regression estimates are small, with a power of 0.8 and bias-corrected bootstraps. Since FIML estimates were used to deal with missing data, this suggests that the sample size is large enough to test our hypotheses.

3 Results

Pairwise correlations between self-compassion (T1), coping (T1 and T2), and subjective well-being / psychopathological symptoms (T1 and T3) are shown in Table 1.

3.1 Associations of Gender, Age, and Student/non-student Status with Self-compassion, Coping, Subjective Well-being, and Psychopathological Symptoms at T1

As shown in Table 2, levels of functional coping, life satisfaction, and stress symptoms at T1 were lower in men than in women. Self-compassion, coping, subjective well-being, and psychopathological symptoms did not differ significantly between diverse vs. male/female individuals (all p-values > 0.05). Older age was associated with higher self-compassion, less functional and less dysfunctional coping, more positive affect, and lower depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms at T1. Students indicated lower self-compassion, more dysfunctional coping, and higher depressive and anxiety symptoms at T1. That is, except for negative affect, each measure was associated with gender (male vs. female, but not diverse vs. male/female), age, and/or student/non-student status at T1, so these variables were controlled for in the analyses.

3.2 Associations Between Self-compassion at T1, Coping at T2, and Subjective Well-being and Psychopathological Symptoms at T3

As shown in Table 3, higher self-compassion at T1 predicted more positive affect, less negative affect, and lower stress symptoms at T3. More functional coping at T2 predicted higher life satisfaction, more positive and less negative affect, and lower depressive and stress symptoms at T3. More dysfunctional coping at T2 predicted lower life satisfaction, less positive and more negative affect, and higher depressive, anxiety, and stress symptoms at T3. Higher self-compassion at T1 predicted more functional (b = 0.13, 95% CI: 0.04, 0.21, p = 0.006) and less dysfunctional (b = -0.15, 95% CI: −0.24, −0.07, p < 0.001) coping at T2.

3.3 Mediation Effects

As shown in Table 4 and Fig. 1, the effects of self-compassion at T1 on negative affect (30.77%) and stress symptoms at T3 (46.15%) were partially mediated by less dysfunctional coping at T2. No other significant mediation effects were found.

4 Discussion

Using data from a 3-wave longitudinal study during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany, we examined whether higher self-compassion predicted higher subjective well-being and lower psychopathological symptoms through more functional and less dysfunctional coping. Our main finding was that less dysfunctional coping partially mediated the effects of higher self-compassion on less negative affect and lower stress symptoms. Consistent with the transactional model of stress and coping (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), this finding supports the idea that self-compassion facilitates an accepting and balanced attitude toward challenges (Neff, 2003b), which prevents dysfunctional coping strategies (e.g., self-blame or substance use) and associated adverse outcomes such as negative affect and stress symptoms.

First, we found that higher self-compassion at T1 predicted more positive affect, less negative affect, and lower stress symptoms at T3, but was not significantly associated with life satisfaction and symptoms of depression and anxiety at T3. These results suggest that self-compassion primarily affected how individuals felt emotionally, but less so how they evaluated their lives during the COVID-19 pandemic. These findings are partially consistent with previous evidence that higher self-compassion is associated with higher affective well-being and lower symptoms of stress (Booker & Dunsmore, 2019; Marsh et al., 2018; Zessin et al., 2015).

Second, we found that more functional coping and less dysfunctional coping at T2 consistently predicted higher subjective well-being and lower psychopathological symptoms at T3, with the sole exception that functional coping at T2 was unrelated to anxiety symptoms at T3. These findings are consistent with cognitive-behavioral models and the idea that the way how individuals respond cognitively and behaviorally to stress is essential to subjective well-being and mental health (Craske, 2010).

In terms of effect sizes, coping predicted subjective well-being and psychopathological symptoms more strongly than self-compassion. These findings might be explained by the fact that self-compassion refers to attitudes, whereas coping refers to actual cognitive and behavioral stress responses in daily life, which might more directly influence how individuals feel. In addition, effect sizes were stronger for dysfunctional than for functional coping, suggesting that the detrimental effects of dysfunctional coping (e.g., self-blame or substance use) on subjective well-being and mental health might be stronger than the beneficial effects of functional coping (e.g., positive reframing or planning).

Third, we found that higher self-compassion at T1 predicted more functional and less dysfunctional coping at T2. These findings are consistent with previous evidence (Ewert et al., 2021) and support the idea that self-compassion (general attitude) acts as a distal predictor and coping (thoughts and behaviors) as a proximal predictor of subjective well-being and mental health during stressful times.

Fourth, we found that less dysfunctional coping mediated (a) nearly one-third of the association between higher self-compassion and less negative affect and (b) nearly half of the association between higher self-compassion and lower stress symptoms. These findings support the idea that an overall positive attitude (self-compassion) prevents dysfunctional thoughts (e.g., self-blame) and behaviors (e.g., substance use) during stressful times, which in turn reduces negative affect and symptoms of stress (Ewert & Schröder-Abé, 2022).

There was no evidence that functional coping mediated the effects of self-compassion on affective well-being or symptoms of stress. This finding is consistent with our result that dysfunctional coping predicted subjective well-being and psychopathological symptoms more strongly than functional coping. It is also plausible that self-compassion directly influences affective well-being and perceived stress independently of (additional) functional coping strategies. For example, higher self-compassion might directly reduce symptoms of stress, so individuals do not need additional functional coping strategies such as emotional and instrumental social support.

Our findings in this regard are partially consistent with previous evidence that the association between higher self-compassion and less negative positive affect was partially mediated by lower disengagement but not by higher engagement coping (Ewert & Schröder-Abé, 2022). Our study extends this previous research by including not only affective but also cognitive well-being (i.e., life satisfaction) and psychopathological symptoms, and by demonstrating that the mediation effects of less dysfunctional coping were specific to negative affect and stress symptoms.

4.1 Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths: it was conducted at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, a particularly stressful and challenging time for many individuals (Robinson et al., 2022; Vindegaard & Benros, 2020; Wu et al., 2021). Self-compassion, functional and dysfunctional coping, subjective well-being, and psychopathological symptoms were assessed longitudinally with well-established scales. In the analyses, we controlled for scores of the mediator (coping, T2) and outcome (subjective well-being, psychopathological symptoms, T3) variables at T1.

However, our study is not without limitations: first, all outcomes were assessed by self-reports, which may be subject to retrospective memory, recall, and reporting bias. Second, our observational results cannot be interpreted causally. A randomized controlled intervention study would be needed to examine whether self-compassion training leads to increases in self-compassion, changes in functional and dysfunctional coping, and, in turn, higher subjective well-being and lower psychopathological symptoms. Third, our study was based on a convenience sample (primarily female students) from German-speaking countries, so generalizability to men, the general population, and other regions and countries may be limited.

Data availability

Openly accessible analysis scripts are attached as supplemental material.

References

Booker, J. A., & Dunsmore, J. C. (2019). Testing direct and indirect ties of self-compassion with subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20, 1563–1585.

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’too long: Consider the brief cope. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 92–100.

Craske, M. G. (2010). Cognitive-behavioral therapy. American Psychological Association.

Diedrich, A., Burger, J., Kirchner, M., & Berking, M. (2017). Adaptive emotion regulation mediates the relationship between self-compassion and depression in individuals with unipolar depression. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 90, 247–263.

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75.

Ewert, C., Buechner, A., & Schroeder-Abé, M. (2023). Stress perception and coping as mediators of the link between self-compassion and affective well-being? Mindfulness, In press.

Ewert, C., Gaube, B., & Geisler, F. C. M. (2018). Dispositional self-compassion impacts immediate and delayed reactions to social evaluation. Personality and Individual Differences, 125, 91–96.

Ewert, C., & Schröder-Abé, M. (2022). Stress processing mediates the link between momentary self-compassion and affective well-being. Mindfulness, 13, 2269–2281.

Ewert, C., Vater, A., & Schröder-Abé, M. (2021). Self-Compassion and coping: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 12, 1063–1077.

Fritz, M. S., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2007). Required sample size to detect the mediated effect. Psychological Science, 18, 233–239.

Glaesmer, H., Grande, G., Braehler, E., & Roth, M. (2011). The German version of the satisfaction with life scale (SWLS). European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 27, 127–132.

Grühn, D., Kotter-Grühn, D., & Röcke, C. (2010). Discrete affects across the adult lifespan: Evidence for multidimensionality and multidirectionality of affective experiences in young, middle-aged and older adults. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 492–500.

Homan, K. J., & Sirois, F. M. (2017). Self-compassion and physical health: Exploring the roles of perceived stress and health-promoting behaviors. Health Psychology Open, 4, 2055102917729542.

Hupfeld, J., & Ruffieux, N. (2011). Validierung einer deutschen version der self-compassion scale (SCS-D) [validation of the German version of the self-compassion-scale]. Zeitschrift Für Klinische Psychologie Und Psychotherapie, 40, 115–123.

Knoll, N., Rieckmann, N., & Schwarzer, R. (2005). Coping as a mediator between personality and stress outcomes: A longitudinal study with cataract surgery patients. European Journal of Personality, 19, 229–247.

Krieger, T., Berger, T., & Grosse Holtforth, M. (2016). The relationship of self-compassion and depression: Cross-lagged panel analyses in depressed patients after outpatient therapy. Journal of Affective Disorders, 202, 39–45.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company.

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 335–343.

MacBeth, A., & Gumley, A. (2012). Exploring compassion: A meta-analysis of the association between self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 545–552.

Marsh, I. C., Chan, S. W., & MacBeth, A. (2018). Self-compassion and psychological distress in adolescents: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 9, 1011–1027.

Muris, P., & Petrocchi, N. (2017). Protection or vulnerability? A meta-analysis of the relations between the positive and negative components of self-compassion and psychopathology. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 24, 373–383.

Neff, K. (2003a). The development and validation of a scale to measure self-compassion. Self and Identity, 2, 223–250.

Neff, K. (2003b). Self-compassion: An alternative conceptualization of a healthy attitude toward oneself. Self and Identity, 2, 85–101.

Nilges, P., & Essau, C. (2015). Die depressions-angst-stress-skalen: Der DASS–ein screeningverfahren nicht nur für schmerzpatienten (Originalien). Der Schmerz, 29, 649–657.

Robinson, E., Sutin, A. R., Daly, M., & Jones, A. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal cohort studies comparing mental health before versus during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Journal of Affective Disorders, 296, 567–576.

Sirois, F. M., Molnar, D. S., & Hirsch, J. K. (2015). Self-compassion, stress, and coping in the context of chronic illness. Self and Identity, 14, 334–347.

StataCorp. (2017). Stata statistical software: Release 15. In StataCorp LLC.

Vindegaard, N., & Benros, M. E. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and mental health consequences: Systematic review of the current evidence. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 89, 531–542.

Watson, D., & Clark, L. (1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the positive and negative affect schedule: Expanded form. University of Iowa.

Wu, T., Jia, X., Shi, H., Niu, J., Yin, X., Xie, J., & Wang, X. (2021). Prevalence of mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 281, 91–98.

Zessin, U., Dickhäuser, O., & Garbade, S. (2015). The relationship between self-compassion and well-being: A meta-analysis. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 7, 340–364.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The authors received no funding for this article. The authors had complete freedom to direct the analysis and its reporting without influence from any sponsors. There was no editorial direction or censorship from any sponsors. The study, including the hypotheses and analysis, was preregistered at https://osf.io/n7asw/?view_only=012ab3087cac42c9abc202fd28f75672.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CH and CE assessed the data. All authors contributed to the conceptualization of the current article. EA conducted the analysis and wrote the manuscript draft. All other authors provided feedback and advice. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript to be submitted.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Ethical Approval

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before collecting the data of the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Asselmann, E., Bendau, A., Hoffmann, C. et al. Self-compassion Predicts Higher Affective Well-being and Lower Stress Symptoms Through Less Dysfunctional Coping: A Three-wave Longitudinal Study During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Happiness Stud 25, 55 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00755-6

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00755-6