Abstract

What are the specific everyday communication experiences—from across people’s social networks—that contribute to well-being? In the present work, we focus on the effects of perceived partner responsiveness in social interactions on various well-being outcomes. We hypothesized that everyday moments of responsiveness indirectly support two key estimates of well-being (hope and life satisfaction) through feelings of social connection. Data were obtained in an experience sampling study collected across ten days (N = 120). Results of dynamic structural equation modeling (DSEM) showed that responsive interaction predicted increases in hope (but not life satisfaction) through social connection. Results also identified reciprocal within-person links between responsive interaction and social connection throughout the day. These findings underscore the importance of responsive everyday communication for fostering social connection across different types of relationships and for supporting people’s capacity for a hopeful life. We discuss the implications of these results for continued research of responsiveness, hope theory, and well-being from a social interaction lens. On a practical level, the mediation pathway involving hope suggests how small changes in our patterns of everyday social interaction can be consequential to the quality of our lives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

When endeavoring to answer the big questions about a well-lived life, it can be beneficial to think small—that is, by focusing on small moments of everyday social interaction we have throughout our days. Humans’ fundamental needs for belonging, as well as their goals related to identity and trust, are pursued in the context of everyday social interaction across our social networks (Leary & Gabriel, 2022; Nezlek et al., 2007; Sandstrom & Dunn, 2014; Weiss et al., 2022). Given this, scholars have long sought to determine the precise features of everyday social interaction that facilitate goals and outcomes related to well-being. An influential line of research in this area is Reis and colleagues’ extensive work on perceived partner responsiveness (i.e., communication behaviors that make someone feel supported, cared for, and validated; Reis et al., 2004). The current study builds upon this work to better understand how moments of responsive communication throughout the day are directly and indirectly linked to feelings of social connection and two estimates of well-being—hope and life satisfaction.

1.1 Extending Research on Perceived Partner Responsiveness

Over the past two decades, research indicates that perceived partner responsiveness contributes to wide-ranging positive cognitive (e.g., increased open-mindedness; Itzchakov & Reis, 2021), health-related (e.g., decreased mortality; Stanton et al., 2019) and relational (e.g., greater intimacy; Debrot et al., 2012) outcomes. The current study builds on this work in three ways. First, we aim to further understand the “downstream consequences” of perceived partner responsiveness in everyday life (Reis et al., 2022). Downstream consequences can be conceptualized at proximal and distal levels. Proximal consequences of responsiveness are those pertinent to contemporaneous cognitive and emotional states, such as changes in positive or negative affect during or immediately following social interaction (Reis, 2001). Distal consequences of responsiveness include longer-term person-level changes in well-being, mental health, and general outlooks on life. These longer-term person-level changes are theorized to emerge from individuals’ accumulation of moments of responsive social interaction over time (Reis, 2001).

Second, we examine the consequences of day-to-day network-wide responsive interaction. Most responsiveness research focuses on the consequences of responsive interaction from a specific relational partner, such as a romantic partner. There is good reason for this, as responsive interaction with individual partners, particularly romantic partners, has been shown to predict relational health and individual well-being over time (e.g., Alonso-Ferres et al., 2020; Selcuk et al., 2016). Nevertheless, we also need to consider the totality of people’s daily social interactions as they communicate with various types of people, including acquaintances and strangers. This is something Reis et al. (2004) specifically noted in their initial proposal of the responsiveness concept. Sampling the network-wide social interactions people have each day might help cast additional light on, and explain greater variance in, the proximal and distal downstream consequences of responsiveness.

Third, we examine a within-day predictor of responsive interaction. Given the many positive effects responsiveness has on people’s lives, it is valuable for theoretical and practical purposes to better understand the factors that make responsiveness more likely to occur—or be perceived—in the context of everyday interaction (Reis & Clark, 2013). Experiences earlier in a person’s day, for instance, might make people more likely to seek out responsive interaction later in the day (Aurora et al., 2022). Additionally, individuals’ emotional and cognitive states entering into a conversation can shape appraisal of a partner’s communication behaviors during the conversation (Reis et al., 2004). Research of this possibility, however, remains limited.

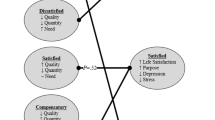

Using the experience sampling method in which we sampled participants’ social interactions over a 10-day period, we address the three opportunities just discussed. The overall goal of this study is to assess possible proximal and distal consequences of network-wide responsive social interaction, while also testing how social connection from earlier in the day potentially shapes perceptions of interaction later in the day. In terms of proximal consequences, we explore how responsiveness is associated with perceived connection to others within (or shortly following) moments of social interaction. In terms of distal consequences, we analyze the effects of responsive interaction on hope (Snyder, 2002) and life satisfaction (Pavot & Diener, 2008) through multilevel mediation modeling. This approach estimates how changes in person-level variables are related to moment-level experiences during social interaction over time. The pathways in the mediation analysis, as will be discussed, emerged from the integration of the responsiveness literature with hope theory (Snyder, 2002) and research on the “bottom-up” construction of life satisfaction (Heller et al., 2004; Hseih, 2003).

1.2 The Effects of Perceived Partner Responsiveness in Everyday Interaction

Perceived partner responsiveness is based on the dual processes of (a) enacted behavior and (b) motivated processing (Reis et al., 2004, 2022). The first process, enacted behavior, concerns the specific verbal and nonverbal behaviors that typify responsive interaction. In short, this process assumes that certain behavioral cues are more responsive than others (Itzchakov et al., 2022; Maisel et al., 2008). The second process, motivated processing, indicates that some of the meaning of communication behavior is filtered through perception (Reis et al., 2004). Positive or negative emotional or cognitive states, for instance, can make people more or less likely to perceive an interaction partner’s behavior as responsive (Reis & Clark, 2013).

Responsiveness was originally proposed as an “organizing construct” encompassing various theoretical perspectives focused on the interlinkages between social interaction and well-being indicators (Reis et al., 2004). Supporting the utility of the responsiveness construct, it has been linked to various positive outcomes, such as perceived psychological safety, interpersonal trust, positive emotion, and openness to others (Reis et al., 2022). Overall, the literature suggests that responsive interaction makes people feel that they are not alone in the world—that there are people around them who “get them” and will care for them even in moments of vulnerability.

When people experience responsive interaction in everyday social interaction they should feel increased feelings of connection to other people (Reis, 2001; Reis et al., 2004). Social connection is defined by Vella-Brodrick et al. (2023) as people’s “subjective sense that they have close and positively experienced relationships with others” (p. 883). Consistent with conceptualizations of loneliness and social isolation, people’s momentary sense of social connection is a mixture of perception and emotion (Cacioppo & Hawkley, 2009; Heinrich & Gullone, 2006). Perceptually, social connection is a valanced assessment of the state of people’s interpersonal relationships. Emotionally, it represents what Ryff and Singer (2003) termed the “co-occurrence of discrete emotions” (p. 1087) concerning affection, security, gratitude, and generalized positivity. Despite the intuitiveness of the link between responsiveness and social connection, it is important to clarify the nature of this link at the within-person level and in the context of everyday life as people interact with various types of relational partners throughout their day. As Reis et al. (2022) recently noted, “partner responsiveness is likely to be a key variable not only in personal relationships, but also in all forms of human sociability in general” (p. 241). This is not to say that all social interaction—be it with strangers or close relational partners—is equally consequential to people’s thoughts and feelings each day, but rather that we cannot discount the contributions that social interaction with non-intimate partners has on well-being (Dunn & Lok, 2022; Kardas et al., 2022; Reis, 2001). In this study, we therefore test how responsive behaviors from various sources throughout the day might lead to increased feelings of social connection (see Fig. 1, lower part).

H1:

Perceived partner responsiveness during everyday interaction positively predicts contemporaneous (i.e., within-moment) feelings of connection to others. In other words, moments with higher-than-normal responsiveness are moments with higher-than-normal feelings of connection.

1.3 Predicting the Reception of Responsive Interaction Throughout the Day

Researchers have often explored the contemporaneous and longitudinal correlates of perceived partner responsiveness behaviors, but exploration of the factors that promote reception of responsiveness, particularly within or across days, is less common. A recent study by Jolink and colleagues (2022), however, exemplifies how responsive interaction and affection are reciprocally associated across days within romantic relationships. The researchers found that partner responsiveness positively predicted same-day affectionate touch, which, in turn, predicted next-day perceived partner responsiveness. Positive emotional experiences thus appear to heighten the probability of perceiving responsiveness in subsequent interactions—namely, across days.

Here, we test the possibility that individuals are more likely to perceive higher levels of partner responsiveness during everyday social interaction (i.e., later in the same day across interaction partners) when they are already feeling higher levels of connection to others (see Fig. 1, lower part). Social connection, in other words, might prime individuals to experience responsive interaction later in the day. We contend that there are three conceptual explanations for why feelings of connection from earlier in the day can lead to responsive interaction later in the day. The first route is through motivated processing, whereby feeling connected makes people more likely to perceive responsive cues when they occur (Reis & Clark, 2013). Various cognitive biases shape how people anticipate and perceive partner behavior during everyday social interaction (Epley et al., 2022; Kardas et al., 2022; Maner et al., 2005). It is well-established, for instance, that negative emotional states (e.g., those indicative of loneliness) can lead interactants to appraise conversations as less enjoyable and more threatening than warranted (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, 2018). Positive emotional states, such as those involved in heightened social connection, might have the opposite effect, making people more attuned to and appreciative of others’ responsive behaviors. From a broaden-and-build perspective, we can assert that feelings of connection trigger an upward spiral effect that positively-biases sensitivity to responsiveness cues throughout the day (Fredrickson & Joiner, 2018).

A second route through which earlier connection can promote later responsiveness is through individuals seeking out interactions and interaction partners that are likely to be responsive. Just as negative affect can suppress individuals’ motivation to seek out social interaction (i.e., solitude inertia; Elmer et al., 2020), feelings of connection might motivate individuals to sustain sociability (Elmer, 2021). Thus, when already feeling connected, people might pursue opportunities for continued social integration, making them more likely to enter interactions that provide responsiveness (Uziel & Schmidt-Barad, 2022).

A third route linking earlier-in-the-day emotional connection to later-in-the-day responsiveness reception is through reciprocation. When individuals feel connected to others, they might be more likely to enact responsiveness themselves during interactions. This is because feelings of social connection can facilitate a sense of openness to others (Itzchakov & Reis, 2021) and prosocial goals (Canevello & Crocker, 2010), which likely manifest in enacted responsiveness behaviors (e.g., high-quality listening and expressions of empathy; Itzchakov et al., 2022; Maisel et al., 2008). Given the power of reciprocity norms in social interaction, which promote interactants’ verbal and nonverbal behavioral adaptation as well as communication convergence, a person’s own responsiveness cues are likely to be reflected back to them by others (Bernhold & Giles, 2020; Burgoon et al., 1993). Feelings of connection, in sum, might evoke later responsiveness via interaction partners’ reciprocated communication.

Given the exploratory nature of the ideas presented herein linking earlier-in-the-day connection to later-in-the-day responsiveness, we pose the following research question:

RQ1:

Do earlier-in-the-day feelings of social connection positively predict later-in-the-day perceived partner responsiveness during everyday interactions?

1.4 Distal Consequences of Responsiveness: Changes in Hope and Life Satisfaction

The final objective of this study is to explore longer-term, or distal, person-level consequences of responsive interaction. We employ a multilevel mediation model (specifically, a 1-1-2 mediation model; see e.g. Preacher et al., 2010) whereby daily responsiveness reception (at the interaction level, or level-1) indirectly predicts changes in hope and life satisfaction (at the person level, or level-2) through feelings of connection to others (at the interaction level, or level-1). Specifically, our hypothesized model (see Fig. 1, upper part) tests the idea that people’s sense of hope and life satisfaction over a 10-day period are at least partly attributable to the experience of responsive interaction and resultant feelings of connection to others during that time period. Although dispositional hope and life satisfaction are conceptualized as relatively stable over time, changes due in part to feelings of relatedness can occur (Heller et al., 2006; Reis et al., 2000; Snyder, 1995).

1.5 Hope

Hope theory (Snyder, 2002) defines hope as a goal-based phenomenon rooted in two cognitive dimensions: pathways and agency thinking. Pathways thinking represents the ability to devise routes toward meaningful goals in life. Agency thinking represents a sense of efficacy to pursue goal pathways, particularly in the face of obstacles. Hope theory states that people’s overall hope is based on the combination of their pathways and agency thinking (Snyder, 2002).

Snyder’s (2002) elaborated hope model broadly outlines how pathways and agency are developed and change. The model assumes that interpersonal experiences, such as supportive communication from caregivers and relational partners—and the emotional warmth those experiences entail—are essential to the development and maintenance of hope across the lifespan (Blake & Norton, 2014; Booker et al., 2021; Jiang et al., 2013; Snyder et al., 1997). Within romantic relationships, recent research indicates that responsive interaction is moderately associated with partners’ hope levels (Zahavi-Lupo et al., 2023). Supporting the link between social connection and hope, an experience sampling study reported that people with higher hope (particularly the pathways dimension) reported greater feelings of connection to others throughout the day (Merolla et al., 2021). Social connection and hope-related thinking (namely, perceived agency) have also been found to be moderately associated over a 13-year period (Vella-Brodrick et al., 2023). Overall, then, research using varied methods shows positive associations between responsiveness, social connection, and aspects of hopeful thinking. Based on hope theory, this suggests that feelings of connection to others, which stem from responsive day-to-day social interaction (Pietromonaco & Collins, 2017; Reis et al., 2004; Rice et al., 2020), can create the interpersonal and emotional scaffolding necessary for the development, maintenance, and enhancement of hopeful thinking. This reasoning is the basis for our second hypothesis, which predicts that everyday moments of responsiveness promote hope over time through feelings of social connection.

H2:

Feelings of connection mediate the effect of perceived partner responsiveness during social interactions on changes in hope.

1.6 Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction is a key component of subjective well-being that reflects a person’s generalized evaluation of the quality of their life (Pavot & Diener, 2008). Although relatively stable over time, life satisfaction is proposed to be sensitive to major life events and changing quality in various life domains, such as work and personal relationships (Heller et al., 2006; Pavot & Diener, 2008). Researchers have traditionally conceptualized life satisfaction development and change from either “top-down” and “bottom-up” approaches (Heller et al., 2004; Hseih, 2003; Pavot & Diener, 2008).

Top-down approaches focus on the variance accounted for in life satisfaction by temperament and personality variables, whereas bottom-up approaches focus on the links between life satisfaction and people’s evaluations of their life circumstances in such areas as finances, work, and personal relationships (Hseih, 2003; Pavot & Diener, 2008). Given our proposal that changes in life satisfaction are partially attributable to aggregated social interaction and emotional experiences over a finite time period, we are adopting a bottom-up approach. Specifically, we are proposing that responsive interaction leads to increased life satisfaction through feelings of social connection. Our intensive longitudinal assessment of this mediation pathways builds upon existing long-term longitudinal research that supports interrelationships between responsiveness, social connection, eudemonic and emotional well-being (Alonso-Ferres et al., 2020; Selcuk et al., 2016; Tasfiliz et al., 2018; Vella-Brodrick et al., 2023). Yet, as noted earlier, our study extends this work not only by testing the proposed mediation pathway within the context of everyday interaction via experience sampling, but also by collecting data on network-wide responsive interaction. Indeed, studies on the longitudinal effects of responsiveness typically assess it with regard to specific romantic relationships (e.g., Alonso-Ferres et al., 2020; Selcuk et al., 2016).

The current study is also unique in that it tests a specific theory-based pathway through which responsiveness should predict life satisfaction. Specifically, we propose that responsiveness positively contributes to life satisfaction (as well as hope) through social connection, which we view as consistent with the Reis and colleagues (2004) initial proposal of responsiveness as an organizing construct for the literature on social interaction, intimacy, and closeness. Still, it is reasonable to question if life satisfaction will change based on social interaction and emotional experiences over a short period of time (i.e., 10 days). In general, such change is plausible, but it might be especially so given the circumstances under which the current data were collected—during the early months of the first-wave of COVID-19 lockdowns in the U.S. (April to June, 2020). This was a period when people’s daily routines and patterns of sociability were upended. Mental health challenges also escalated for many people due to health concerns for themselves and loved ones (Pfefferbaum & North, 2020). Such experiences might have destabilized people’s life satisfaction estimates and potentially made them more sensitive than normal to the quality and supportiveness of their daily interpersonal experiences (Ammar et al., 2020; Zacher & Rudolph, 2021). These ideas are captured in our third and final hypothesis.

H3:

Feelings of connection mediate the effect of perceived partner responsiveness during social interactions on changes in life satisfaction.

2 Method

2.1 Participants and Procedures

Participants (N = 120) were undergraduate students at a large university on the western coast of the United States who were recruited via an email advertising the study. Participants were informed that the aim of the study was to better understand how people communicate in daily life. The average age of participants was 20.56 years (range = 19–23, SD = 1.11). Participants could identify with multiple gender identities and self-describe their identity; 81% of identified as female and 19% as male. Participants were able to select multiple races and ethnicities. Approximately 46% identified as Asian, 46% White, 18% Latina/o/x, 5% Black/African American, 5% Native American, and 2% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander.

Prior to the study, research assistants instructed each participant on how to download the experience sampling iOS or Android smartphone application (i.e., Ilumivu’s mEMA System) to their mobile device. Participants were also informed they would receive a $40 e-gift card if they fully completed the study (80% or higher completion rate). Because these data were collected at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, all contact with participants was remote. The researchers also reminded participants that they should adhere to the US. Centers for Disease Control public health safety guidelines while participating in the study.

On the first day of the study (i.e., the day before the 10-day experience sampling portion began), participants completed a presurvey questionnaire in the app that assessed various individual difference and well-being variables. Over the next 10 days, participants were asked to complete brief daily questionnaires about their “in-the-moment” experiences six times a day. Participants were signaled by the survey app through their phone’s native notification system six times per day randomly between 9:00 AM and 7:00 PM with up to two reminder notifications for missed surveys. Participants were also signaled a seventh time each evening to complete an end-of-day diary questionnaire, but that data is not relevant to this study. Of the total 7,200 experience sampling questionnaires (120 participants × 10 days × 6 assessments per day), 6,108 were at least partially completed corresponding to a compliance rate of 84.8%. A post-survey that was largely identical to the pre-survey was then sent the day after the experience sampling period. Of note, beginning on day 4 of the 10-day experience sampling period, approximately two-thirds of the participants received additional messages through the app related to positive communication as part of a pilot study. As discussed later, we examined the potential influence of these messages in our analyses and found no significant effects.

2.2 Presurvey and Postsurvey Measures

2.2.1 Hope

Overall hope was measured on the pre- and post-surveys using Snyder et al.’s (1991) 12-item Adult Hope Scale. Item responses were based on a five-point response scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’; 5 = ‘strongly agree’). The measure contains four items each for the pathways (e.g., “I can think of many ways to get the things in life that are important to me”) and agency (“I energetically pursue my goals”) dimensions of hope. The measure also contains four filler items (e.g., “I feel tired most of the time”) that are not used. An overall hope estimate is constructed by averaging the pathways and agency items. Reliability estimates for the hope measures on the pre- and post-surveys were α = 0.68 and α = 0.76, respectively. See Table 1 for descriptive statistics for this measure and all remaining measures in this study.

2.2.2 Life Satisfaction

Life satisfaction was assessed in the pre- and post-surveys using Deiner et al.’s (1985) five-item Satisfaction with Life Scale. Participants indicated, on a five-point scale ranging from 1 (‘strongly disagree’) to 5 (‘strongly agree’), how content they were with their life (e.g., “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing”). The life satisfaction measure reliabilities on the pre- and post-surveys were α = 0.84 and α = 0.87, respectively.

2.3 Experience Sampling Measures

2.3.1 Responsiveness

If participants indicated they had been in a social interaction in the last 10 min of the survey signal, they were asked to assess the degree to which their interaction partner made them feel respected, cared for, and supported (Reis, 2012). The mean of these three items, which had response options ranging from 1 (‘not at all’) to 5 (‘extremely’), served as the index of responsiveness. Internal consistency was estimated as multilevel McDonald’s ω (ω within = 0.95; ω between = 0.99).

2.3.2 Connection

Momentary reports of social connection were assessed using a single-item measure “At this moment, how close and connected do you feel to other people?”. Participants responded to this item whether they were alone or had been in social interaction. Responses ranged from 1 (‘no connection’) to 7 (‘a great deal of connection’).

2.3.3 Covariates

First, we controlled for the nature of the participants’ relationship to the person they were communicating with. Relationship establishment level was measured on a seven-point scale ranging from 1 (‘no established relationship/stranger’) to 7 (‘established relationship’). Second, we controlled for the communication channel used for the interaction. Channel was based on four options: face-to-face (68%), video calls (14%), text messaging/SMS (14%), and voice-only phone calls (5%). The categorical variable was split into three dummy variables with face-to-face communication as the reference category. Third, we controlled for gender. Fourth, we controlled for participants’ placement into one of three categories on day 4 of the study (i.e., control group, daily message group, and repeated measure group). These groups were created as part of pilot for a smartphone-based intervention focused on positive communication. The control group received no messages, the daily group received a morning message about ideas for positive communication, and the repeated message group received messages based on earlier scores on measures, such as loneliness. Groups were split into two dummy variables with the control group as the reference group.

2.4 Data Analysis

We used dynamic structural equation models (DSEM; Hamaker et al., 2018) to test our hypotheses and research question. This modeling approach combines the strengths of multilevel structural equation modeling to account for the nested data structure (i.e., repeated assessments from each participant) with features of time series modeling to examine lead-lag associations among the experience sampling data. Figure 2 depicts the conceptual model tested.

Results of the DSEM to test the interplay among responsiveness, connection, life satisfaction, and hope. Note: Figure depicts standardized estimates [95% credible intervals]. Estimates whose 95% credible interval covers zero are depicted in grey. Black circles represent parameters that were estimated as random effects. Life Sat = Life Satisfaction. Covariates and covariance are not depicted in this figure. See full Mplus output for details on these parameters: (https://osf.io/nts94/?view_only=fdb9a15733f74dc6bb5ba250fc558893)

On Level-1 (the within-person level), we specified a model with autoregressive effects for responsiveness and connection. That is, person j’s perceived responsiveness at time t (\({resp}_{j,t}\)) was predicted by j’s perceived responsiveness at time t-1 (\({resp}_{j,t-1}\)), and person j’s connection at time t (\({conn}_{j,t}\)) was predicted by j’s connection at time t-1 (\({conn}_{j,t-1}\)). To test H1, we added a directed path from responsiveness (\({resp}_{j,t}\)) to contemporaneous connection (\({conn}_{j,t}\)). Research question 1 was addressed by adding a lagged effect from \({conn}_{j,(t-1)}\) to \({resp}_{j,t}\) to examine whether connection predicts changes in perceived responsiveness at a later moment in the day. Random effects were estimated for these two regression coefficients, the two autoregressive effects, and the two residual variances (allowing individuals to differ in the amount of their within-person variance of connection and responsiveness as in a location scale model; Hedeker et al., 2012). Relationship establishment level and communication channel were added as covariates on Level-1 (directed paths from these covariates to both \({resp}_{j,t}\) and \({conn}_{j,t}\) were estimated; not shown in Fig. 2).

On Level-2 (the between-person level), hope (life satisfaction) at posttest was predicted by hope (life satisfaction) at pretest. Further, both hope and life satisfaction at posttest were predicted by person j’s average connection (\({conn}_{j}\)) and by person j’s average responsiveness (\({resp}_{j}\)). To approach our mediation hypotheses (H2 and H3), a directed path from \({resp}_{j}\) to \({conn}_{j}\) was added and the indirect effects from responsiveness to life satisfaction and hope via connection were estimated. Directed effects from the covariates (i.e., relationship establishment level, communication channel, gender, and condition) to average connection (\({conn}_{j}\)) and the two post assessments (hope, life satisfaction) were added. Covariances among responsiveness and the two pre-assessments (hope, life satisfaction) were added as was a residual covariance between posttest hope and posttest life satisfaction.

DSEM requires a Bayesian estimator. We used the Mplus default settings for model priors and estimated the model using two Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) chains and using a thinning factor of 20. Per chain, results from 3,000 iterations were retained of which the first 50% were discarded as burn-in. Hence, the posterior distribution is based on 3,000 samples. In the following, we report the median of the posterior distribution as point estimate and the associated 95% credible interval (CI) for each parameter. Model parameters whose 95% CI does not contain 0 are considered statistically significantly different from 0. Lagged effects were estimated for a time interval of 2 h using the tinterval option in Mplus.

3 Results

Table 1 depicts descriptive statistics of the key variables. The intra-class correlation coefficients (ICCs) suggested that about 67.7% of the variance in responsiveness and 65.6% of the variance in connection were attributed to within-person fluctuations.

3.1 DSEM

Model convergence was evaluated using the potential scale reduction (PSR) which was satisfactory, with a maximum PSR = 1.018. Visual inspection of trace plots and autocorrelation plots revealed no irregularities. The central parameters of the model are depicted in Fig. 2; for the full model results, see the Mplus output in the accompanying OSF repository (https://osf.io/nts94/?view_only=fdb9a15733f74dc6bb5ba250fc558893).

3.1.1 Within-Person Associations

Both connection, β = 0.253, 95% CI [0.206, 0.301], and responsiveness, β = 0.132 [0.079, 0.184], showed autoregressive effects across time, indicating that an individual tended to report higher connection (responsiveness) on moments after they experienced higher connection (responsiveness) than they usually do. With regard to our first hypothesis, there was a statistically meaningful positive contemporaneous association between responsiveness and connection, β = 0.320 [0.287, 0.354]: Moments with higher-than-usual responsiveness were also moments with higher-than-usual connection, in line with H1. Further, in response to RQ1, there was a positive time-lagged association between connection and responsiveness, β = 0.093 [0.046, 0.143]: When a participant reported a higher level of connection they reported increases in their responsiveness at the next measurement occasion.Footnote 1 Responsiveness, β = 0.272 [0.233, 0.307], but not connection, β = − 0.028 [-0.060, 0.009], was higher after interactions with more established interaction partners.Footnote 2

3.1.2 Between-Person Associations

Both hope, β = 0.512 [0.362, 0.647], and life satisfaction, β = 0.723 [0.583, 0.825], were rather stable across the observation period. Participants who reported higher average levels of responsiveness reported higher levels of connection as shown by a positive between-person effect, β = 0.458 [0.270, 0.626].

After controlling for the pretest measures and connection, responsiveness had no direct effect on either hope, β = − 0.030 [-0.210, 0.151], or life satisfaction, β = − 0.091 [-0.256, 0.072], at posttest. Connection was significantly and positively associated with hope, β = 0.321 [0.114, 0.524], but not life satisfaction at posttest, β = 0.147 [-0.041, 0.333]. To examine if the data were consistent with our mediation hypotheses (H2 and H3), we inspected the indirect effects of responsiveness on hope (life satisfaction) at posttest via connection. This (unstandardized) indirect effect was statistically significant for hope, ab = 0.109 [0.036, 0.212], but not life satisfaction, ab = 0.088 [-0.022, 0.228]. These mediation results support H2 (regarding change in hope), but not H3 (regarding change in life satisfaction).

4 Discussion

This research advances the study of perceived partner responsiveness and well-being in the context of everyday social interaction in three ways. First, this study provides further evidence of the link between perceived partner responsiveness and proximal and distal outcomes pertaining to well-being. Proximally, responsive interaction was linked to momentary social connection. Distally, over the course of a 10-day period, aggregate responsive interaction, through aggregate social connection, was associated with increased hope (but not life satisfaction) at the person-level. Second, this study demonstrated that the links between responsiveness, social connection, and hope exist within the context of network-wide social interaction, as opposed to one-time or repeated interactions with a specific relationship partner. Third, this study casts light on a key within-day predictor of responsiveness. Specifically, earlier-in-the-day social connection was associated with greater likelihood of receiving responsive interaction approximately two hours later. We discuss these contributions, their role in future research, and the limitations of this study.

4.1 Reciprocal Links Between Responsiveness and Social Connection

In support of the first hypothesis, results based on experience sampling data provide evidence (at the within-person level of analysis) that responsiveness experienced throughout the day is associated with increased social connection. This supports fundamental ideas about the value of perceived partner responsiveness proposed by Reis and colleagues (Reis et al., 2004) and underscores more general theoretical claims by communication scholars regarding the consequentiality of everyday social interaction for shaping perceptions of the self and others (Sigman, 1998). Demonstrating links between responsive interaction and social connection is also important given that feelings of connection are fundamental drivers of behavior in everyday life (Leary & Gabriel, 2022).

In addition to the association found between responsiveness and contemporaneous social connection, results indicated that feelings of connection are linked to later-in-the-day reports of responsiveness. This suggests that social connection potentially primes reception and perception of responsiveness throughout the day. Reis et al. (2022) have called for additional research on the downstream consequences of responsiveness (i.e., along the lines of H2 and H3 in this study), but it is also important to explore the predictors of responsiveness to understand what facilitates this important form of communication. We identified three routes through which earlier-in-the-day feelings of connection can shape later-in-the-day responsive interaction. First, positive emotion associated with social connection can lead individuals to be more open and attuned to responsive behavior transpiring during social interaction (see, e.g., Fredrickson & Joiner, 2018). Second, feelings of connection from earlier in the day might motivate people to seek out continued sociability (Elmer, 2021; Uziel & Schmidt-Barad, 2022), placing them in social situations likely to provide responsive interaction. Third, consistent with theoretical perspectives of communication accommodation and behavioral adaption (Bernhold & Giles, 2020; Burgoon et al., 1993), interaction partners might be inclined to converge communicatively to the responsive behaviors enacted by the people who enter interactions with heightened social connection. This study cannot determine which, if any, of these routes best explains the positive link between earlier-in-the-day connection and later-in-the-day responsiveness, but these routes are ripe for further empirical investigation.

It is worth noting that although we have framed the above routes from the perspective of moments of social interaction with heightened social connection, we must also consider the moments of social interaction with low-level social connection. From this vantage point, the results suggest that a vicious cycle might exist—when people feel disconnected from others in one part of the day, they are continually less likely to receive responsiveness throughout the remainder of the day. In this way, feelings of disconnection are reified in people’s day-to-day interaction patterns, such that disconnection begets disconnection via insufficient rewarding interaction (Merolla et al., 2022).

4.2 Responsive Interaction and Hope

Unlike the results for H1 and RQ1, the results for H2 and H3 focused on the downstream consequences of responsiveness and social connection over a 10-day period. Results were in line with a mediation model whereby responsiveness was associated with social connection (both collected at level-1), which in turn was associated with changes in hope from time 1 (pre-survey) to time 2 (post-survey) over the course of the study. These results provide novel support for hope theorists’ claims regarding the critical roles that supportive interaction and feelings of connection to others play in fostering hopeful mindsets (Snyder, 2002). To date, research linking hope to interpersonal communication processes has typically focused on hope as a predictor of behavior (either cross-sectionally or longitudinally) or as a within-day outcome (e.g., Merolla et al., 2021). To our knowledge, the current results are the first to show how interpersonal communication experiences and perceptions of social connection potentially serve as inputs to changes in hope across several days. Overall, the current results suggest that small moments of connection in daily life are implicated in the larger process of hope development and maintenance (see, e.g., the elaborated hope model; Snyder, 2002). This is encouraging from practical standpoint because it suggests that we might be able to help instill hope in others by engaging with them more responsively in moments of daily social interaction.

Responsive interaction and social connection were not, however, related to changes in life satisfaction over the study period. We hypothesized that day-to-day responsive interaction and social connection contributed to the “bottom-up” construction of life satisfaction (Hseih, 2003; Pavot & Diener, 2008). The lack of support for this hypothesis might stem from the 10-day period being too short to capture changes in life satisfaction. Had we used a longer time period, we might have observed greater changes in participant’s reports of life satisfaction. Indeed, longitudinal research linking responsiveness, social connection, and well-being have typically been conducted across several years. It is also plausible that life satisfaction is such a global well-being construct that the contributions of day-to-day interpersonal and emotional experiences are drowned out by other factors, such as the quality of people’s school, work, financial, and heath situations. Thus, when individuals evaluate the global quality of their life, they might be less focused on the immediate state of their social life, instead focusing on a more holistic assessment involving longer-range estimates. Such an assessment would suppress the impact that near-term social experiences (good, bad, or otherwise) have on life satisfaction ratings. In contrast to life satisfaction, hope focuses more narrowly on specific goal pathways and agency (Snyder, 2002), potentially rendering hope estimates more sensitive to near-term social experiences. As Snyder and colleagues have argued, goals relevant to hope are often shaped and pursued with the support of (and in support of) others (Snyder et al., 1997). Thus, consistent with the current study’s findings, when people have a strong sense of being cared for and connected to others, it fuels their goal pathways and agency.

4.3 Limitations and Future Research

The current results are based on a specific group (undergraduate students at a west coast university in the U.S.) during an extraordinary time period (the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic). Thus, the results must be contextualized based on these factors. Given that stay-at-home mandates were in effect during the data collection, it is possible that this situation heightened the importance and effects of responsive interaction and social connection. Further, given that many participants were likely living with, or in close proximity to, non-family members during this time period (e.g., roommates, neighbors, work associates for participants whose jobs might have qualified them as “essential workers”), this might have intensified the contribution of responsiveness to feelings of connection from “non-intimate” partners. Additionally, it is possible that the uncertainty and distress caused by the pandemic destabilized people’s hope levels, leading to more change than we might typically observe over a short time period. It is plausible, then, that the results are unique to the time period in which the data were collected.

Additional limitations stem from the possibility that the results reflect unique experiences of young adults. The current sample was composed of people in and around their early twenties. This a period when social relationships, such as friendships, play outsize roles in shaping identity and well-being (Efeoglu & Sen, 2022). Although such relationships continue to be vital throughout the life course, it remains to be seen if the current results, particularly with regard to changes in hope over time, are the same for individuals in middle and later life. Middle and later life are periods characterized by numerous life transitions that can alter relationship network composition and social capital (English & Carstensen, 2014). Research also indicates that network-level factors, such as relationship stability, affect how people pursue life goals, which suggests that network-level relational factors are relevant to people’s sense of hope (Faris & Felmlee, 2018). Moreover, relational and communication needs and goals, as well as time orientations toward hope-based pathways and agency, appear to shift over the lifespan (Bernhold & Gasiorek, 2020; Wrobleski & Snyder, 2005). These changes could shape the strength of associations between responsiveness, social connection, and hope for participants at different stages of life. Given research on the dynamic spreading of positive emotion, it is also plausible that positive interaction experiences cascade across groups of people (Fowler & Christakis, 2008). Future research can therefore go beyond individual-level analysis and further consider how social interaction shapes well-being throughout networks.

In addition to replication efforts across groups and time periods, future research should examine other features of responsive interaction, namely participants’ own perceived responsiveness. Although it is common in studies of responsiveness to focus on perceptions of other people’s behavior, intriguing research questions pertain to the predictors and consequences of one’s own responsive behaviors. For instance, does social connection from earlier in the day lead people to “pay it forward” and enact greater responsiveness with others later in the day? Does responsiveness received from others promote responsiveness given to others over time (and vice versa)? Alternatively, do low levels of social connection suppress people’s inclination to enact responsiveness? In addition to these questions, future research should collect more detailed data on the what is actually discussed during sampled social interactions to determine the role that responsiveness and social connection play in shaping what people talk about (see, e.g., Mehl, 2017). Future work might also take a finer-grained approach to assessing the influence of temporal factors, such as time of day, which has been linked to positive and negative emotional experience (English & Carstensen, 2014). Further, drilling down into the specific perceptual and affective components of social connection might also help explain the precise mechanism operating within the mediation pathway involving hope. As we noted earlier, social connection likely involves a pooling of perceptions and discrete emotions (Heinrich & Gullone, 2006; Ryff & Singer, 2003). As such, specific socioemotional factors involved in perceptions of social connection, such as gratitude or optimism, might play particularly important roles in shaping hope. Future research could attempt to parse the unique contributions of discrete emotions.

Overall, this study cast additional light on perceived partner responsiveness in everyday social interaction. Results supported foundational claims about links between responsiveness and social connection within interactions. Results also offered novel insight into the ways in which social connection promotes reception of responsiveness throughout the day and how responsive interaction and social connection contribute to hope over time. As research on partner responsiveness continues to mount, the value of this “organizing construct” linking moments of interaction to general well-being becomes ever clearer.

Notes

We also evaluated an exploratory model that was identical to the hypothesized one with one additional path—a cross-time path from within-person responsiveness (t) to social connection (t + 1). The results of the two models were nearly identical, and the additional path from responsiveness (t) to social connection (t + 1) was not statistically significant, β = − 0.021 [-0.066, 0.024].

We also analyzed differences in the level-1 variables across the four communication channels. There were no statistically significant differences across communication channels for responsiveness, F(3, 3075) = 1.485, p = .217, and none of the post-hoc contrasts were statistically significant (Tukey adjustment for multiple testing). There were, however, statistically significant differences for connection based on channel, F(3, 3051) = 29.106, p < .001. Specifically, the following four post-hoc contrasts were statistically significant (Tukey adjustment for multiple testing): connection was higher for (a) face-to-face interaction compared to video-based interaction, b = 0.211, p = .017; (b) face-to-face interaction compared to text-based interaction, b = 0.659, p < .001; (c) phone interaction compared to text-based interaction, b = 0.365, p = .048; and (d) video-based interaction compared to text-based interaction, b = 0.448, p < .001.

References

Alonso-Ferres, M., Imami, L., & Slatcher, R. B. (2020). Untangling the effects of partner responsiveness on health and well-being: The role of perceived control. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37(4), 1150–1171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519884726.

Ammar, A., Chtourou, H., Boukhris, O., Trabelsi, K., Masmoudi, L., Brach, M., Bouaziz, B., Bentlage, E., How, D., Ahmed, M., Mueller, P., Mueller, N., Hsouna, H., Aloui, A., Hammouda, O., Paineiras-Domingos, L., Braakman-Jansen, A., Wrede, C., & Bastoni, S. (2020). COVID-19 home confinement negatively impacts social participation and life satisfaction: A worldwide multicenter study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 6237. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17176237.

Aurora, P., Disabato, D. J., & Coifman, K. G. (2022). Positive affect predicts engagement in healthy behaviors within a day, but not across days. Motivation Emotion, 46, 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-021-09924-z.

Bernhold, Q. S., & Gasiorek, J. (2020). Older adults’ perceptions of their own and their romantic partners’ age-related communication and their associations with aging well, depressive symptoms, and alcohol use disorder symptoms. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 37, 1172–1192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519890413.

Bernhold, Q. S., & Giles, H. (2020). Vocal accommodation and mimicry. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 44, 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10919-019-00317-y.

Blake, J., & Norton, C. (2014). Examining the relationship between hope and attachment: A meta-analysis. Psychology, 5, 556–565. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2014.56065.

Booker, J. A., Dunsmore, J. C., & Fivush, R. (2021). Adjustment factors of attachment, hope, and motivation in emerging adult well-being. Journal Happiness Studies, 22, 3259–3284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00366-5.

Burgoon, J. K., Dillman, L., & Stem, L. A. (1993). Adaptation in dyadic interaction: Defining and operationalizing patterns of reciprocity and compensation. Communication Theory, 3, 295–316. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.1993.tb00076.x.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2018). Loneliness in the modern age: An evolutionary theory of loneliness (ETL). Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 58, 127–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.aesp.2018.03.003.

Cacioppo, J. T., & Hawkley, L. C. (2009). Perceived social isolation and cognition. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13, 447–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2009.06.005.

Canevello, A., & Crocker, J. (2010). Creating good relationships: Responsiveness, relationship quality, and interpersonal goals. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99, 78–106. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018186.

Debrot, A., Cook, W. L., Perrez, M., & Horn, A. B. (2012). Deeds matter: Daily enacted responsiveness and intimacy in couples’ daily lives. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 617–627. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028666.

Deiner, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with Life Scale. The Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Dunn, E., W., & Lok, I. (2022). Can sociability be increased? In J. P. Forgas, W. Crano, & K. Fiedler (Eds.), The psychology of sociability: Understanding human attachment. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003258582.

Efeoglu, B., & Sen, C. K. N. (2022). Rejection sensitivity and mental well-being: The positive role of friendship quality. Personal Relationships, 29, 4–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12403.

Elmer, T. (2021). In which direction does happiness predict subsequent social interaction? A commentary on Quoidbach et al. (2019). Psychological Science, 32, 955–959. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F0956797620956981.

Elmer, T., Geschwind, N., Peeters, F., Wichers, M., & Bringmann, L. (2020). Getting stuck in social isolation: Solitude inertia and depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129, 713–723. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000588.

English, T., & Carstensen, L. L. (2014). Emotional experience in the mornings and the evenings: Consideration of age differences in specific emotions by time of day. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00185.

Epley, N., Kardas, M., Zhao, X., Atir, S., & Schroeder, J. (2022). Undersociality: Miscalibrated social cognition can inhibit social connection. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 26, 406–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2022.02.007.

Faris, R., & Felmlee, D. H. (2018). Best friends for now: Friendship network stability and adolescents’ life course goals. In D. Alwin, D. Felmlee, & D. Kreager (Eds.), Social networks and the life course: Integrating the development of human lives and social relational networks. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-71544-5_9.

Fowler, J. H., & Christakis, N. A. (2008). Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: Longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart Study. Bmj, 337, a2338. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a2338.

Fredrickson, B. L., & Joiner, T. (2018). Reflections on positive emotions and upward spirals. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13, 194–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/2F1745691617692106.

Hamaker, E. L., Asparouhov, T., Brose, A., Schmiedek, F., & Muthén, B. (2018). At the frontiers of modeling intensive longitudinal data: Dynamic structural equation models for the affective measurements from the COGITO Study. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 53, 820–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2018.1446819.

Heinrich, L. M., & Gullone, E. (2006). The clinical significance of loneliness: A literature review. Clinical Psychology Review, 26, 695–718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.04.002.

Heller, D., Watson, D., & Ilies, R. (2004). The role of person versus situation in life satisfaction: A critical examination. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 574–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.574.

Heller, D., Watson, D., & Ilies, R. (2006). The dynamic process of life satisfaction. Journal of Personality, 74, 1421–1450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2006.00415.x.

Hseih, C. M. (2003). Counting importance: The case of life satisfaction and relative domain importance. Social Indicators Research, 61, 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:102135413266.

Itzchakov, G., & Reis, H. T. (2021). Perceived responsiveness increases tolerance of attitude ambivalence and enhances intentions to behave in an open-minded manner. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 47, 468–485. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0146167220929218.

Itzchakov, G., Reis, H., & Weinstein, N. (2022). How to foster perceived partner responsiveness: High-quality listening is key. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 16, e12648. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12648.

Jiang, X., Huebner, S., & Hills, K. J. (2013). Parent attachment and early adolescents’ life satisfaction: The mediating effect of hope. Psychology in the Schools, 50, 340–352. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21680.

Jolink, T. A., Chang, Y. P., & Algoe, S. B. (2022). Perceived partner responsiveness forecasts behavioral intimacy as measured by affectionate touch. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48, 203–221. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0146167221993349.

Kardas, M., Kumar, A., & Epley, N. (2022). Overly shallow? Miscalibrated expectations create a barrier to deeper conversation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 122, 367–398. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000281.

Leary, M. R., & Gabriel, S. (2022). The relentless pursuit of acceptance and belonging. In A. J. Elliot (Ed.), Advances in motivation science (Vol. 9, pp. 135–178). Academic.

Maisel, N. C., Gable, S. H., & Strachman, A. (2008). Responsive behaviors in good times and in bad. Personal Relationships, 15, 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2008.00201.x.

Maner, J. K., Kenrick, D. T., Becker, D. V., Robertson, T. E., Hofer, B., Neuberg, S. L., Delton, A. W., Butner, J., & Schaller, M. (2005). Functional projection: How fundamental social motives can bias interpersonal perception. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.88.1.63.

Mehl, M. R. (2017). The electronically activated recorder (EAR): A method for the naturalistic observation of daily behavior. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 26, 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0963721416680611.

Merolla, A. J., Bernhold, Q., & Peterson, C. (2021). Pathways to connection: An intensive longitudinal examination of state and dispositional hope, day quality, and everyday interpersonal interaction. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38, 1961–1986. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F02654075211001933.

Merolla, A. J., Hansia, A., Hall, J. A., & Zhang, S. (2022). Moments of connection for the disconnected: People with negative relations with others experience less, but benefit more from, positive everyday interaction. Communication Research, 49, 838–862. https://doi.org/10.1177/00936502211005890.

Nezlek, J. B., Schütz, A., & Sellin, I. (2007). Self-presentational success in daily social interaction. Self and Identity, 6, 361–379. https://doi.org/10.1080/15298860600979997.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with Life Scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743976070175694617439760701756946.

Pfefferbaum, B., & North, C. S. (2020). Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. New England Journal of Medicine, 383, 510–512. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2008017.

Pietromonaco, P. R., & Collins, N. L. (2017). Interpersonal mechanisms linking close relationships to health. American Psychologist, 72(6), 531–542. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000129.

Preacher, K. J., Zyphur, M. J., & Zhang, Z. (2010). A general multilevel SEM framework for assessing multilevel mediation. Psychological Methods, 15(3), 209–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020141.

Reis, H. T. (2001). Relationship experiences and emotional well-being. In C. D. Ryff & B. H. Singer (Eds.), Emotion, social relationships, and health (pp. 57–86). Oxford University Press.

Reis, H. T. (2012). Perceived partner responsiveness as an organizing theme for the study of relationships and well-being. In L. Campbell & T. J. Loving (Eds.), Interdisciplinary research on close relationships: The case for integration (pp. 27–52).

Reis, H. T., & Clark, M. S. (2013). Responsiveness. In J. A. Simpson & L. Campbell (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of close relationships (pp. 400–423). Oxford University Press.

Reis, H. T., Sheldon, K. M., Gable, S. L., Roscoe, J., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). Daily well-being: The role of autonomy, competence, and relatedness. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26, 419–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167200266002.

Reis, H. T., Clark, M. S., & Holmes, J. G. (2004). Perceived partner responsiveness as an organizing construct in the study of intimacy and closeness. In D. J. Mashek, & A. P. Aron (Eds.), Handbook of closeness and intimacy (pp. 201–225). Erlbaum.

Reis, H. T., Itzchakov, G., Lee, K. Y., & Yan, R. (2022). Sociability matters: Downstream consequences of perceived partner responsiveness in social life. In J. P. Forgas, W. Crano, & K. Fiedler (Eds.), The psychology of sociability: Understanding human attachment. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003258582.

Rice, T. M., Kumashiro, M., & Arriaga, X. B. (2020). Mind the gap: Perceived partner responsiveness as a bridge between general and partner-specific attachment security. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17, 7178. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197178.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. H. (2003). The role of emotion on pathways to positive health. In R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of Affective sciences (pp. 1083–1104). Oxford University Press.

Sandstrom, G. M., & Dunn, E. W. (2014). Is efficiency overrated? Minimal social interactions lead to belonging and positive affect. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 5, 437–442. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550613502990.

Selcuk, E., Gunaydin, G., Ong, A. D., & Almeida, D. M. (2016). Does partner responsiveness predict hedonic and eudaimonic well-being? A 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78, 311–325. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12272.

Sigman, S. J. (1998). Relationships and communication: A social communication and strongly consequential view. In R. L. Conville, & L. E. Rogers (Eds.), The meaning of relationship in interpersonal communication (pp. 47–67). Praeger.

Snyder, C. R., Harris, C., Anderson, J. R., Holleran, S. A., Irving, L. M., Sigmon, S. T., Yoshinobu, L., Gibb, J., Langelle, C., & Harney, P. (1991). The will and the ways: Development and validation of an individual-differences measure of hope. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60, 570–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.4.570.

Snyder, C. R. (1995). Conceptualizing, measuring, and nurturing hope. Journal of Counseling and Development, 73, 355–360. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.1995.tb01764.x.

Snyder, C. R. (2002). Hope theory: Rainbows in the mind. Psychological Inquiry, 13, 249–275. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327965PLI1304_01.

Snyder, C. R., Cheavens, J., & Sympson, S. C. (1997). Hope: An individual motive for social commerce. Group Dynamics: Theory Research and Practice, 1, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2699.1.2.107.

Stanton, S. C. E., Selcuk, E., Farrell, A. K., Slatcher, R. B., & Ong, A. D. (2019). Perceived partner responsiveness, daily negative affect reactivity, and all-cause mortality: A 20-year longitudinal study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 81, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1097/2FPSY.0000000000000618.

Tasfiliz, D., Selcuk, E., Gunaydin, G., Slatcher, R. B., Corriero, E. F., & Ong, A. D. (2018). Patterns of perceived partner responsiveness and well-being in Japan and the United States. Journal of Family Psychology, 32(3), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000378.

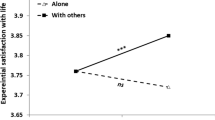

Uziel, L., & Schmidt-Barad, T. (2022). Choice matters more with others: Choosing to be with other people is more consequential to well-being than choosing to be alone. Journal of Happiness Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00506-5.

Vella-Brodrick, D., Joshanloo, M., & Slemp, G. R. (2023). Longitudinal relationships between social connection, agency, and emotional well-being: A 13-year study. Journal of Positive Psychology, 18, 883–893. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2022.2131609.

Weiss, A., Burgmer, P., & Hoffmann, W. (2022). The experience of trust in everyday life. Current Opinion in Psychology, 44, 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2021.09.016.

Wrobleski, K. K., & Snyder, C. R. (2005). Hopeful thinking in older adults: Back to the future. Experimental Aging Research, 31, 217–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/0361073059091545.

Zacher, H., & Rudolph, C. W. (2021). Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 76, 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000702.

Zahavi-Lupo, T., Lazarus, G., Pshedetzky-Shochat, R., Bar-Kalifa, E., Refoua, E., Gleason, M. E. J., & Rafaeli, E. (2023). His, hers, or theirs? Hope as a dyadic resource in early parenthood. Journal of Positive Psychology, 18, 557–572. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2022.2093780.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant awarded to Andy J. Merolla from the UCSB Academic Senate.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.J.M.: Study design, hypothesis and research question development, writing of the manuscript. A.B.N.: Data analysis and manuscript editing. C.D.O.: Study design and writing of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the University of California, Santa Barbara Human Subjects Committee (Protocol Number 4-20-0158).

Competing Interests

The authors of this study have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Merolla, A.J., Neubauer, A.B. & Otmar, C.D. Responsiveness, Social Connection, Hope, and Life Satisfaction in Everyday Social Interaction: An Experience Sampling Study. J Happiness Stud 25, 7 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00710-5

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-024-00710-5