Abstract

The aim of this study was to examine the heterogeneity of change of posttraumatic growth (PTG) among people living with HIV (PLWH) in a 1-year prospective study. The goal was also to identify sociodemographic and clinical covariates and differences in baseline coping strategies. Particularly, time since diagnosis and positive reframing coping were of special interest. The sample consisted of 115 people with medically confirmed diagnosis of HIV infection. The participants filled out paper-and-pencil questionnaires three times with an interval of 6 months, including also sociodemographic and clinical data. Four trajectories of PTG were identified: curvilinear, low stable, high stable, and rapid change. Participants’ gender, education level, CD4 count and time since HIV diagnosis occurred to be significant covariates of class membership. Positive reframing and self-distraction differentiated only between the high stable and the rapid change trajectory, with lower values in the latter. The study results call for attention to the complexity of PTG patterns in a face of struggling with HIV infection. Specifically, interventions in clinical practice should take into account the fact that there is no single pattern of PTG that fits all PLWH and that these differences may be related to the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics as well as to coping strategies representing meaning-making mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It has been more than two decades since Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996) coined the term posttraumatic growth (PTG), which substantially altered the theory and practice of traumatic stress studies (Infurna & Jayawickreme, 2019; Tedeschi et al., 2018). Specifically, the introduction of the PTG concept stimulated new lines of research on positive changes among survivors of traumatic life events, which became one of the leading research fields in positive psychology, which was formed somewhat later (Seligman & Csikszentmihalyi, 2000). It also resulted in the construction of several theoretical models of PTG, which operationalize this phenomenon differently (e.g., Linley & Joseph, 2004; Maercker & Zoellner, 2004; Pals & McAdams, 2004; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996, 2004). Unfortunately, the multiplicity of theoretical approaches to PTG did not translate satisfactorily into a consensus on the meaning of this term, and so the problem of what PTG actually is and how PTG should be measured remains (Jayawickreme et al., 2021; Jayawickreme & Blackie, 2014).

On the one hand, Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996, 2004) treat PTG as an outcome of complex, mainly cognitive, processing of traumatic experience. Conversely, other researchers define PTG as a process for finding meaning after trauma (Pals & McAdams, 2004), an element of psychological well-being (Linley & Jospeh, 2004), or even a manifestation of compensatory illusion (Maercker & Zoellner, 2004). Although there is no general consensus on how to operationalize PTG, the majority of authors record similar changes observed among people exposed to highly stressful life events, which do not have to be traumatic by definition (Jayawickreme & Blackie, 2014). These changes include more satisfying interpersonal relationships, finding new life possibilities, greater appreciation of life, openness to spiritual issues, and enhanced perception of personal strength (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 2004).

Aforementioned models of PTG have been studied intensely in recent years (Infurna & Jayawickreme, 2019; Taku et al., 2020). Nevertheless, some alternative theoretical explanations of PTG still have not been addressed adequately in the literature. One of these explanations focuses on thorough coping process in the aftermath of experiencing highly stressful events (Tennen & Affleck, 2009). It should be noted that Tedeschi and Calhoun (1996) have already highlighted that not only experiencing the traumatic event itself but a method to cope with it foster growth via facilitation of cognitive processing of trauma. From that time, several studies have shown that different coping strategies may promote or hinder PTG as a response to a life-threatening illness (see for review: Casellas-Grau et al., 2017; Rzeszutek & Gruszczyńska, 2018). More specifically, meaning-focused coping strategies, especially positive reappraisal, have been found to predict PTG among cancer patients (e.g., Sears et al., 2003) and people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH) (e.g., Siegel et al., 2005). Conversely, avoidance coping strategies, e.g., denial or substance was found to hinder the growth among patients struggling with terminal illness (Sears et al., 2003). Nevertheless, a majority of studies in this area have been cross-sectional and longitudinal studies on the PTG-coping association among PLWH showed no significant relationship (Rzeszutek et al., 2017). These findings call for more advanced methodological designs (Hamama-Raz et al., 2019).

Tennen and Affleck (2009) proposed the operationalization of PTG as a form of coping, where aforementioned facets of PTG (e.g., enhanced perception of personal strength, openness to spirituality) can be attributed with dealing with consequences of traumatic events. In other words, PTG may serve for trauma survivors as a kind of active coping strategy to find the meaning of trauma. Moreover, it was also reported that PTG can help enhance more adaptive coping strategies to deal with current and future life stressors (Park et al., 2005). However, some authors have observed that PTG can also represent defensive coping with experiencing growth serving as a positive illusion (Cheng et al., 2018). Thus, it still not known whether particular coping strategies promote or hinder PTG or whether PTG facilitates adaptive or maladaptive coping, as the vast majority of those studies applied cross-sectional frameworks (Hamama‐Raz et al., 2019). In fact, this problem can only be addressed in longitudinal studies. First step in answering this question could be to examine if people representing different trajectories of PTG also differ in their baseline coping strategies.

Diagnosis of and life with a potentially terminal somatic disease is a very strong stressor, which has been classified as an event meeting the criterion of a traumatic stressor and which can lead to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; APA, 1994; Kangas et al. 2005). HIV/AIDS has these consequences; roughly 30 percent to even 64 percent of PLWH meet the diagnostic criteria of PTSD (Sherr et al., 2011). However, an increasing number of authors have observed positive changes among this group of patients, comprising the phenomenon of PTG (e.g., Cieślak et al., 2009; Milam, 2004, 2006; Siegel et al., 2005; Rzeszutek et al., 2017).

When exploring the issue of PTG accompanying the trauma of a life-threatening disease, one should also clarify the essence of this type of trauma, which is not easy and provokes controversy, especially among PLWH (Neigh et al., 2016). Edmondson (2014) proposed a PTSD model associated with enduring somatic threat. The posttraumatic symptoms accompanying patients have a complex etiology and variable dynamics. Although they are usually initiated by the moment of diagnosis, they also result from a later struggle with the disease, constant awareness of the real life threat, and, in some cases (see PLWH), very strong social stressors (Sherr et al., 2011). Namely, trauma experienced by such patients applies not only to the past (see diagnosis) but is also a continuous process induced by internal (somatic) factors related to the present and/or future. This latter distinguishes it from traditionally understood traumatic stressors as an event external to a person that has happened in the past (see APA, 1994, 2013). Taking the above into consideration, there is no agreement on when the critical moment that can potentially trigger a growth experience will be, nor on how much time will have to elapse from that moment until the appearance of PTG. Most researchers have observed that the critical moment is the moment of diagnosis (Casellas-Grau et al., 2017). However, other authors have argued that positive changes may also appear many years after diagnosis, as was found often among PLWH (Sawyer et al., 2010). Thus, it has been suggested to incorporate the trajectory models into studying both resilience and psychopathology among individuals exposed to traumatic events to better understand the unique patterns of adaptation (Galatzer-Levy et al., 2018).

Such approach is called person-centered as it allows identifying groups of people who in an examined phenomenon represent the highest possible similarity inside a given group, while at the same time representing a maximum diversity across these groups (e.g. Laursen & Hoff, 2006). In this way, a data-driven heterogeneity regarding the magnitude and direction of change can be detected in the sample. On the basis of previous studies, it is already known that averaging individual processes will not provide an accurate explanation for the observable differences in psychological functioning between PLWH, which still exist even after adjusting for the course and progression of the disease itself. There is probably no single trajectory of PTG among PLWH, and the conditions underlying these changes need an explanation.

Relatively little attention has been devoted to this topic so far, and existing studies, largely maintained in a cross-sectional design, bring about a rather fragmentary and inconsistent picture of PTG among PLWH (Rzeszutek & Gruszczyńska, 2018; Sawyer et al., 2010). In particular, most authors have mainly sought to document PTG prevalence among PLWH and relate it to selected clinical variables, which has led to ambiguous conclusions. For example, some studies have demonstrated a relationship between PTG and better immune parameters (Milam, 2004, 2006), while other researchers have not observed this relationship (Littlewood et al., 2008). Similar ambiguous results refer to PTG in relation to other clinical variables, such as adherence to treatment (see Łuszczyńska et al., 2012 vs. Littlewood et al., 2008) or the status of HIV/AIDS (see Milam, 2004 vs. Littlewood et al., 2008). The relatively strongest consensus prevails regarding the lack of association between PTG and the duration of HIV infection (e.g., Garrido-Hernansaiz et al., 2017; Łuszczyńska et al., 2012; Milam, 2004, 2006), which provokes the question of what really induces PTG in this group of patients. That is, should the aforementioned positive changes be attributed to the ongoing adjustment to or coping with HIV/AIDS or do they represent a real growth that goes beyond an adaptation to illness (Sawyer et al., 2010), usually defined as a return to pre-illness well-being level (Lyubomirsky, 2010).

Even much less research has been devoted to the role of coping in explaining differences in PTG among PLWH. Until now four such studies have been identified, result of which point mainly to beneficial effects of a wide range of meaning-focused strategies (Kraaij et al., 2008; Rzeszutek, et al., 2017; Siegel et al., 2005) as well as problem-focused strategies (Kraaij et al., 2008, Ye et al., 2017). An enhancing potential of avoidant emotion-focused strategies should also not be neglected (Kraaij et al., 2008). Nevertheless, all of these studies applied a variable -center approach, which even if utilized longitudinal data can only to some extent overcome the typical drawbacks observed in PTG studies (Pat-Horenczyk et al., 2016). That is, at best their results illustrate general patterns and ignore a clinically important heterogeneity of PTG trajectories among PLWH.

2 Current Study

Taking the aforementioned research gaps into a consideration, the aim of our study was to examine patterns of PTG change among PLWH in a 1-year prospective study and to establish their sociodemographic and clinical correlates as well as related differences in coping strategies. More specifically, we wanted to verify three hypotheses in the first study among PLWH in a person-centered approach, which can be considered an added value to research on PTG in general, where person-centered longitudinal analysis is still very scant (Cheng et al., 2018; Hamama-Raz et al., 2019).

On the basis of the few longitudinal studies so far, we expected that changes of PTG among PLWH will be heterogeneous, i.e., PLWH will differ in terms of staring point as well as amount and direction of change of PTG throughout the study period (Hypothesis 1). However, as the study was conducted among PLWH at least 1 year after diagnosis, which suggested that for the majority of them adaptation to the disease may already be achieved (Sawyer et al., 2010), the most numerous trajectories should present stability of PTG rather than changes. Still these trajectories may differ with regard to years after the diagnosis as well as other clinical and sociodemographic variables (Hypothesis 2). Thus, we examined a possibility of heterogeneous trajectories of PTG and wanted to identify their specific covariates (Husson et al., 2017). Finally, there should be mechanisms underlying long-term changes in PTG (Infurna & Jayawickreme, 2019). The strategies of coping with stress caused by chronic disease may not just undermine or facilitate development of PTG but may also be important factors for its sustainability. Particularly, it refers to meaning-focused coping, which essence is a cognitive reformulation of a stressful situation as valuable and beneficial without changing its objective parameters. As such, it supports a reconstruction of the positive meaning given to life, violated by an irreversible stressful event, which is essential for an induction of a recovery process (Jayawickreme et al., 2021). This role has been empirically verified in uncontrollable and long-lasting conditions (Folkman, 1997; Moskowitz et al., 2009; Prati & Pietrantoni, 2009). Therefore, while this part of the study is more exploratory, we still expect that among tested coping strategies positive reappraisal should be associated with more beneficial PTG trajectories (Hypothesis 3).

3 Method

3.1 Participants and Procedure

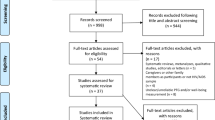

The sample consisted of 115 adults with a medical diagnosis of HIV infection. Of 470 patients taking part in a larger cross-sectional project conducted in naturalistic setting during standard medical care at out-patient clinic of the state hospital of infectious diseases, 115 (25 percent) agreed to leave their personal contact data to participate in a 1-year longitudinal study. There were no significant differences in all sociodemographic and clinical characteristics between the two groups, except for education level. Namely, people with secondary and higher education were more likely to participate in the longitudinal study than people with secondary or vocational education (χ2 = 7.57, df = 1, p = 0.006). The written informed consent was obtained from each person before the study begun and there was no remuneration for participation. The participants completed three times at 6-month interval a paper-and-pencil set of the questionnaires, which was distributed by the authors of this study and professional interviewers. The eligibility criteria were being at least 18 years old, having a confirmed medical diagnosis of HIV+, and undergoing antiretroviral treatment. Eligibility criteria also included indicating in the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI, see, Measures) a diagnosis of HIV infection as a traumatic event. The exclusion criteria included HIV-related cognitive disorders, which were screened by medical doctors. The study was approved by the local ethics commission. Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the sample.

3.2 Measures

To measure the intensity of posttraumatic growth, the Posttraumatic Growth Inventory was used (PTGI; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). As in the original version, it consists of 21 statements that describe various changes resulting from traumatic or highly stressful events, which are listed at the beginning of the questionnaire. In our study, the participants were directly instructed to focus on their diagnosis of HIV infection as the event since which the changes may have happened. They responded to each statement on a six-point scale, starting from 0 = I did not experience this change as a result of the crisis to 5 = I experienced this change to a very great degree as a result of the crisis. In the current study, only the global PTG score was obtained (Park & Helgeson, 2006) by summarizing all the answers. The Cronbach coefficient for this indicator was 0.96, 0.95, and 0.94 for the first, second, and third measurement points, respectively.

Strategies of coping with stress were assessed by Brief-COPE Inventory (Carver, 1997). This questionnaire comprises 28 items with a Likert-like response scale from 0 = I haven’t been doing this at all to 3 = I’ve been doing this a lot. It results in 14 subscales, with two items per each, illustrating a wide range of coping strategies, including self-distraction, active coping, denial, substance use, use of emotional support, use of instrumental support, behavioral disengagement, venting, positive reframing, planning, humor, acceptance, religion, and self-blame. In the instruction, participants were informed to focus on their ways of coping with the disease during last the four weeks when providing their answers. Indicators were obtained by adding together the relevant answers and then averaging the values. With only two items per scale, the Cronbach’s alpha ranged from 0.40 (humor) to 0.86 (substance use).

3.3 Data Analysis

To test homogeneity versus heterogeneity of change of PTG in the sample, latent class growth modeling (LCGM; Nagin, 2005) was used. We began with estimating a single trajectory model where homogeneity of change in the whole sample is presumed (1-class solution). Next, additional models were estimated with an increasing number of trajectories (n + 1 class solution). Both linear and quadratic time trends were examined. A final model was chosen based on comparisons of several indicators (Nylund et al., 2007). For Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the Sample-size Adjusted BIC (SABIC), and Akaike’s Information Criterion (AIC), the lowest values suggest the best solution. Entropy indicates a quality of a class separation from 0 to 1, where 1 evidences a prefect classification (Muthén & Muthén, 2000). Another evaluation of goodness of fit is provided by the results of the Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT, McLachlan & Peel, 2000), which compares neighboring models. Finally, a size of the smallest class is a practical criterion. In general, classes smaller than 5 percent of the sample are considered spurious and unreplicable (Hipp & Bauer, 2006), although in clinical samples they may still have a value.

After establishing the optimal number and shape of trajectories, we used the bias-adjusted three-step approach (Bakk et al., 2013) to identify significant covariates of a trajectory membership among sociodemographic and clinical variables presented in Table 1. In the final step, we tested, by means of one-way ANOVA, if members representing different trajectories used different coping strategies at baseline. Due to variance heteroscedasticity and unequal group sizes for multiple post hoc comparisons, we implemented bootstrapping with 500 samples to form a 95 percent confidence interval with the bias-corrected and accelerated method (BCa 95% CI). Data analysis was performed using the Latent GOLD 5.1.0.19007 and IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.

4 Results

4.1 Missing Data and Descriptive Statistics

We noted 29 percent dropout between the first and the last measurement of PTG, but missing data can be regarded as missing at random (Little’s MCAR test: χ2 = 19.64, df = 20, p = 0.481). Also, there were no significant differences between initial and final sample for any sociodemographic or clinical variable. Thus, all the data from the 115 participants were included in the analysis, using the full information maximum likelihood algorithm. The descriptive statistics of longitudinally assessed PTG and baseline coping for this sample are provided in Table 2.

4.2 Trajectories of PTG

Table 3 presents a summary of model selection indices of latent class growth analysis. For the model with one trajectory, both linear (s1 = 9.6, z = 1.72, ns) and quadratic (s2 = − 4.2, z =− 1.53, ns) slope were insignificant, suggesting a lack of change of PTG at the level of the sample means. However, models with more than one trajectory were better fitted to the data. The lowest BIC was noted for the model with four trajectories. This model also provided the highest data separation among competing models. Finally, the insignificant BLRT for the model with five trajectories indicated a better fit for the model with one fewer class. Thus, in spite of a quite small frequency of the lowest class, four trajectories were examined further. The obtained solution is plotted in Fig. 1.

Trajectory 1, which has the highest number of participants (46 percent of the sample), describes a curvilinear pattern of PTG change (s1 = 12.9, z = 2.33, p < 0.05; s2 =− 7.0, z =− 2.55, p < 0.05). Trajectory 2 (25 percent of the sample), which has the highest starting point, was stable during the time of the study (s1 = 14.4, z = 0.81, ns; s2 = − 1.5, z = − 0.55, ns). For trajectory 3 (22 percent of the sample), although the pattern seems curvilinear due to large standard errors, these changes are insignificant (s1 =− 22.0, z = − 1.82, ns; s2 = 9.6, z = 1.67, ns). Finally, trajectory 4, which has the lowest number of participants (7 percent of the sample), although modelled as curvilinear, represents rather piecewise growth with the turning point at the second measurement. A steep rise from the lowest to the highest PTG values is followed by a small decrease between the second and third measurement.

4.3 Sociodemographic and Clinical Covariates of PTG Trajectories

Among covariates of class membership, the significant effects were noted for gender (Wald = 17,413.26, p < 0.001), age (Wald = 14.11, p = 0.003), and education level (Wald = 5977.39, p < 0.001), as well as for two HIV-related characteristics: CD4 count (Wald = 26.47, p < 0.001) and, expectedly, time since diagnosis (Wald = 8.75, p = 0.033). There were no differences for relationship status, years of antiretroviral therapy (ART), or AIDS stage. The summary of results is presented in Table 3. In general, trajectory 4 comprises a subgroup of men only, the oldest ones but with a relatively short time since diagnosis (although it differs significantly only from trajectory 2) and the lowest CD4 count. For the highest and stable trajectory 2, the most distinguishing characteristics of members are a relatively higher representation of women than in other groups, a lower education level, and the longest time since HIV diagnosis. Members of trajectory 1 (curvilinear) and 3 (low stable) are similar in terms of covariates, with a difference only for gender ratio: a higher prevalence of women is present in the curvilinear trajectory (see Table 4).

4.4 Coping Strategies Across PTG Trajectories

Out of the 14 analyzed coping strategies, only two significant differences between the groups were noted. Both of them are differences between trajectory 4, rapid change, and trajectory 2, the highest and stable trajectory. These are positive reframing (mean difference =− 0.7; BCa 95% CI [− 1.4, − 0.1]) and self-distraction (mean difference = − 0.8; BCa 95% CI [− 1.4, − 0.3]), which were significantly lower in trajectory 4 (see Table 5).

5 Discussion

The results of our study are consistent with our first hypothesis that PTG trajectories among study participants would be heterogeneous. We managed to identify four PTG trajectories (curvilinear, high/stable, low/stable, and rapid change), which can be considered an added value to research on PTG in general, where person-centered longitudinal analysis is still very scant (Cheng et al., 2018; Hamama-Raz et al., 2019).

In general, as expected, we noted only null to modest changes in PTG for most of the sample, which was also observed in other studies (Garrido-Hernansaiz et al., 2017; Rzeszutek et al., 2017). However, the obtained picture is more complex. Particularly, the curvilinear pattern of PTG change, which had the most participants and which showed a small increase followed by a small decline of growth throughout the year, appears intriguing and may suggest that the growth process for those struggling with disease is not linear as described by traditional PTG models (Tedeschi & Callhoun, 2004). Until now the curvilinear nature of PTG has been studied mostly in case of the PTG- PTSD association, and predominantly in studies applying the variable-centered approach (see review and meta-analysis; Shakespeare-Finch & Lurie-Beck, 2014). Our result can also be an argument in favor of PTG specificity in the context of serious chronic diseases, where experiencing health threats is a dynamic process linked not only to the past (e.g., diagnosis), but also to the present and future (Edmondson, 2014). Additionally, for PLWH, social reception of the disease should be considered when looking for explanations of the dynamics of PTG, as this construct, although assuming deep intrapersonal changes, can potentially be sensitive to situational factors (trait-like vs. state-like PTG; Blackie et al., 2017).

However, to address this issue empirically, repeated measurement of PTG should be accompanied by repeated measurement of disease status, disease-related stressors, and other potentially significant psychosocial factors. This will enable researchers to look for the correlated change (Schwarzer et al., 2006). In this context, the trajectory of rapid PTG change is particularly interesting, especially as a very similar pattern of PTG was observed among women with breast cancer (Danhauer et al., 2015). Further analyses showed the distinctive characteristics of this group in our study, which indicates the validity of its separation, which will be discussed later in more detail (Table 5).

In line with the second hypothesis, selected sociodemographic and clinical variables were significant covariates of being a member of a given trajectory. Especially, as expected, time since HIV diagnosis was the longest for PLWH in the highest and stable PTG trajectory. The fact that they had been infected with HIV from 4 to 6 years longer than representatives of other trajectories may suggest a real growth, i.e., one that goes beyond an adaptation to illness understood as regaining pre-diagnosis well-being (Hamama-Raz et al., 2019). In cancer and HIV/AIDS, PTG shortly after the diagnosis may serve mainly as a way to cope with illness-related distress (Sawyer et al., 2010). With time elapsed since diagnosis, a transition between illusory and constructive growth (see Maercker & Zoellner, 2004) is more likely due to its processual nature, including for some people going through a stage of struggling PTG (Pat-Horenczyk et al., 2016). In our study, this struggling is observed in the members of the rapid change PTG trajectory. They also have the shortest time since diagnosis and the lowest CD4 count. Together with older age, which also means late onset of HIV infection, it creates a different psychological situation, in which the process is not finished yet or PTG may be harder to achieve. PTG for this group may also be triggered by participation in the study (Tedeschi & Kilmer, 2005), especially as this group consists only of well-educated men.

The several studies conducted among both the general population (Vishnevsky et al., 2010) and PLWH (Rzeszutek et al., 2016) point to higher PTG among women than men. This was also the case in our study. The role of education is more equivocal, since it is related directly or indirectly to other personally and socially valued resources (Hobfoll, 1989). In our study, lower education level was associated with the probability of being a member of the high/stable PTG trajectory, which may support the thesis that PTG, even if stabilized and not necessary illusory, may have a compensatory character in the face of lack of other resources to gain control over one’s own life (Bellizzi & Blank, 2006). However, since this cannot be regarded as a striking difference, this topic needs further research.

Our last hypothesis that baseline use of positive reframing would be beneficial to PTG was supported up to a point. However, use of positive reframing differed significantly between members of two trajectories. It was lowest among members of the rapid change trajectory, whereas it was highest among members of the high and stable trajectory. This finding refers directly to the aforementioned concept of constructive growth. Specifically, according to Pat-Horenczyk et al. (2016), constructive or real PTG in case of an illness should be based on a joint increase in PTG and salutary coping, whereas illusory growth is an increase only in PTG.

Members of this rapid change trajectory had also lower baseline use of self-distraction. The subscale includes such items as I’ve been turning to work or other activities to take my mind off things or I’ve been doing something to think about it less, such as going to movies, reading etc. (Carver, 1997). Folkman’s (1997) research suggests that these strategies can reduce negative emotions or enhance positive emotions, depending on person-situation interaction. In the latter case, they may provide a detachment from chronic stress and replenish personal resources necessary to sustain coping (Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000; Fredrickson, 1998). In this sense, cognitive and behavioral efforts described under the term “self-distraction,” which has been viewed as a maladaptive strategy, may act far beyond avoidance by creating positive events and activities and be a part of meaning-focused coping (Folkman, 1997; Folkman & Moskowitz, 2000). This line of reasoning has been recently directly confirmed in context of chronic stressors in the study by Waugh et al. (2020). The overlap between avoidance and positive distraction was weak and only the latter was related to higher well-being and positive emotions and lower depressive symptoms.

In this manner, the picture becomes clearer. In our sample, there were no significant differences in coping strategies between three trajectories of PTG. The only difference concerns two trajectories, both with the highest PTG, but one is stable, whereas the other is unstable, with a steep increase. Thus, it is not that a high baseline level of meaning-focused coping is associated with real PTG. Rather, the point is that a low baseline level of meaning-focused coping is associated with illusory or struggling PTG. Still, the mechanism of growth in this latter group remains unknown since it cannot be attributed in our sample to strategies usually positively related to PTG (Prati & Pietrantoini, 2009).

5.1 Strengths and Limitations

Our study has several strengths, including a longitudinal person-centered approach with three measurements of PTG in a special and difficult to access clinical sample, which is PLWH. Nevertheless, a few limitations should be mentioned. Firstly, our study sample was heterogonous with regard to time since HIV diagnosis. We examined a role of his variable directly in our study, but still, this means that participants may have been assessed at very different stages of the PTG process. Secondly, the final sample was relatively small, with unequal gender ratio, which although representing adequately a percentage of women living with HIV in a general population (UNAIDS, 2019), may lead to low power to detect heterogeneity of trajectories among this group. Thirdly, the PTGI questionnaire was created to operationalize positive changes after vast categories of traumatic events and, therefore, may not be sufficiently sensitive to capture a distinctiveness of chronic illness-related threat (Casselas-Grau et al., 2017), especially with strong probability of social stigmatization (Rueda et al., 2016). Similarly, low reliability of some coping subscales due to their two-item length may indicate a lack of validity. It was the case for instance or the self-distraction subscale, suggesting that its avoidant or meaning-making function could be not only person- but item-related. Finally, our participants were relatively highly functional PLWH, with high treatment compliance and CD4 counts similar to the general population (UNAIDS, 2019). In samples of PLWH more diverse on clinical and sociodemographic characteristic perhaps different pattern of results could be obtained. On the other hand, several studies on clinical vs. psychosocial variables in PTG among PLWH showed a stronger effect of the latter. Alternatively speaking, it was found that the self-reported PTG may be related mostly to psychological and social factors, rather than to clinical characteristics of HIV infection (Rzeszutek & Gruszczyńska, 2018). However, a lack of objective reports on the clinical status in such studies is the major shortcoming, which is also the case in our study. Thus, the strength of the effect of clinical variables may be underestimated due to a weakness of measurement, but it does not change the fact that a enormous progress in HIV treatment (UNAIDS, 2019) allows for successful medical control of HIV infection with a reduced burden of compliance.

6 Conclusions

The results of our study show that PTG among PLWH should be treated as a process for which both level and dynamics are related to time since diagnosis and basic sociodemographic characteristics of PLWH. Rapid growth, when co-occurring with a low level of meaning-focused coping, may suggest struggling PTG, prone to further changes. On the other hand, high use of this coping strategy is not a hallmark of high and stable PTG, which makes a role meaning-making mechanism ambiguous and calls for searching for potential modifiers of its effectiveness. From a clinical point of view, our research inform about a complexity of growth process in the case of dealing with HIV infection (Cafaro et al., 2016; Tedeschi et al., 2018), which on the general level corresponds with recently described by Bonnano (2021) challenges in predicting adjustment trajectories after experiencing various types of trauma. This topic needs further investigation, especially as the access to psychological care for the HIV/AIDS population is still very limited (National AIDS Centre, 2019) and does not take into account cultural and contextual differences (Rzeszutek et al., 2017). Specifically, a key finding for planning and implementing interventions at the individual, group, or community level is that there is no one pattern of PTG that fits all PLWH.

References

American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). Washington D.C: Author.

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington D.C: Author.

Bakk, Z., Tekle, F., & Vermunt, J. (2013). Estimating the association between latent class membership and external variables using bias-adjusted three-step approaches. Sociological Methodology. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081175012470644

Bellizzi, K. M., & Blank, T. O. (2006). Predicting posttraumatic growth in breast cancer survivors. Health Psychology, 25, 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.25.1.47

Blackie, L., Jayawickreme, E., Tsukayama, E., Forgeard, M., Roepke, A. M., & Fleeson, W. (2017). Posttraumatic growth as positive personality change: Developing a measure to assess within-person variability. Journal of Research in Personality, 69, 22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2016.04.001

Bonanno, G. (2021). The resilience paradox. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 12(1), 1942642. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1942642

Cafaro, V., Iani, L., Costantini, M., & Di Leo, S. (2016). Promoting post-traumatic growth in cancer patients: A study protocol for a randomized controlled trial of guided written disclosure. Journal of Health Psychology, 24, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316676332

Carver, C. S. (1997). You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 4, 92–100.

Casellas-Grau, A., Ochoa, C., & Ruini, C. (2017). Psychological and clinical correlates of posttraumatic growth in cancer: A systematic and critical review. Psycho-Oncology, 26, 2007–2018. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.4426

Cheng, C., Ho, S., & Hou, Y. (2018). Constructive, illusory, and distressed posttraumatic growth among survivors of breast cancer: A 7-year growth trajectory study. Journal of Health Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105318793199

Cieslak, R., Benight, B., Schmidt, N., Łuszczyńska, A., Curtin, E., & Clark, A. (2009). Predicting posttraumatic growth among Hurricane Katrina survivors living with HIV: The role of self-efficacy, social support, and PTSD symptoms. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 22, 449–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800802403815

Danhauer, S., Russell, G., Douglas, L., Case, S., Sohl, S., Tedeschi, R., Addington, E. L., Triplett, K., Van Zee, K. J., Naftalis, E. Z., Levine, B., & Avis, N. E. (2015). Trajectories of posttraumatic growth and associated characteristics in women with breast cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine., 49, 650–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-015-9696-1

Edmondson, D. (2014). An enduring somatic threat model of posttraumatic stress disorder due to acute life-threatening medical events. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 8, 118–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12089

Folkman, S. (1997). Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science & Medicine, 45, 1207–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00040-3

Folkman, S., & Moskowitz, J. T. (2000). Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist, 55, 647–654. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.6.647

Fredrickson, B. L. (1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology, 2, 300–319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300

Galatzer-Levy, I. R., Huang, S. H., & Bonanno, G. A. (2018). Trajectories of resilience and dysfunction following potential trauma: A review and statistical evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 63, 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2018.05.008

Garrido-Hernansaiz, H., Murphy, P., & Alonso-Tapia, J. (2017). Predictors of resilience and posttraumatic growth among people living with HIV: A longitudinal study. AIDS and Behavior, 21, 3260–3270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-017-1870-y

Hamama-Raz, Y., Pat-Horenczyk, R., Roziner, I., Perry, S., & Stemmer, S. (2019). Can posttraumatic growth after breast cancer promote positive coping? A cross-lagged study. Psycho-Oncology, 28, 767–774. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5017

Hipp, J. R., & Bauer, D. J. (2006). Local solutions in the estimation of growth mixture models. Psychological Methods, 11, 36–53. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.11.1.36

Hobfoll, S. (1989). The ecology of stress. Hemisphere Publishing Corporation.

Husson, O., Zebrack, B., Block, R., Embry, L., Aguilar, C., Hayes-Lattin, B., & Cole, S. (2017). Posttraumatic growth and well-being among adolescents and young adults (AYAs) with cancer: A longitudinal study. Supportive Care in Cancer, 25, 2881–2890. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-017-3707-7

Infurna, F., & Jayawickreme, E. (2019). Fixing the growth illusion: New directions for research in resilience and posttraumatic growth. Current Directions in Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721419827017

Jayawickreme, E., & Blackie, L. (2014). Posttraumatic growth as positive personality change: Evidence, controversies, and future directions. European Journal of Personality, 28, 312–331. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1963

Jayawickreme, E., Infurna, F., Alajak, K., Blackie, L., Chopik, W., Chung, J., Dorfman, A., Fleeson, W., Forgeard, M., Frazier, P., & Furr, R. M. (2021). Post-traumatic growth as positive personality change: Challenges, opportunities, and recommendations. Journal of Personality, 89, 145–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12591

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) Report (2019). https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/2019-UNAIDS-data

Kangas, M., Henry, J., & Bryant, R. (2005). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder following cancer. Health Psychology, 24, 579–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.24.6.579

Kraaij, V., Garnefski, N., Schroevers, M. J., Sm, V., Witlox, R., & Maes, S. (2008). Cognitive coping, goal self-efficacy and personal growth in HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Patient Education and Counselling, 72, 301–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.04.007

Laursen, B., & Hoff, E. (2006). Person-centered and variable-centered approaches to longitudinal data. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 52, 377–389. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2006.0029

Linley, P., & Joseph, S. (2004). Positive change following trauma and adversity: A review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 17, 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOTS.0000014671.27856.7e

Littlewood, R., Vanable, P., Carey, M., & Blair, D. (2008). The association of benefit finding to psychosocial and behavior adaptation among HIV+ men and women. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31, 145–155. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-007-9142-3

Lyubomirsky, S. (2010). The how of happiness: A practical approach to getting the life you want. Piatkus.

Łuszczyńska, A., Durawa, A., Dudzinska, M., Kwiatkowska, M., Knysz, B., & Knol, N. (2012). The effects of mortality reminders on posttraumatic growth and finding benefits among patients with life-threatening illness and their caregivers. Psychology & Health, 27, 1227–1243. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2012.665055

Maercker, A., & Zoellner, T. (2004). The Janus face of self-perceived growth: Toward a two-component model of posttraumatic growth. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 41–48.

McLachlan, G. J., & Peel, D. (2000). Finite mixture models. Wiley.

Milam, J. E. (2004). Posttraumatic growth among HIV/AIDS patients. Journal of Applied and Social Psychology, 34, 2353–2376. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb01981

Milam, J. E. (2006). Posttraumatic growth and HIV disease progression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 817–827. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.817

Moskowitz, J., Hult, J., Bussolari, C., & Acree, M. (2009). What works in coping with HIV? A meta-analysis with implications for coping with serious illness. Psychological Bulletin, 135, 121–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014210

Muthén, B., & Muthén, L. K. (2000). Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcoholism, Clinical and Experimental Research, 24, 882–891.

Nagin, D. (2005). Group-based modeling of development. Harvard University Press.

National AIDS Centre. (2019). Report on the schedule for the implementation of the National Program for HIV Prevention and Combat AIDS for 2017–2021 for 2019. Katowice.

Neigh, G. N., Rhodes, S. T., Valdez, A., & Jovanovic, T. (2016). PTSD co-morbid with HIV: Separate but equal, or two parts of a whole? Neurobiology of Disease, 92, 116–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2015.11.012

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14, 535–569.

Pals, J., & McAdams, D. (2004). The transformed self: A narrative understanding of posttraumatic growth. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 65–69.

Park, C., Mills-Baxter, M., & Fenster, J. (2005). Post-traumatic growth from life’s most traumatic event: Influences on elders’ current coping and adjustment. Traumatology, 11, 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1177/153476560501100408

Park, C., & Helgeson, V. (2006). Introduction to the special section: Growth following highly stressful life events—Current status and future directions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74, 791–796. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.791

Pat-Horenczyk, R., Saltzman, L., Hamama-Raz, Y., Perry, S., Ziv, Y., Ginat-Frolich, R., & Stemmer, S. (2016). Stability and transitions in posttraumatic growth trajectories among cancer patients: LCA and LTA analyses. Psychological Trauma, 8, 541–549. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000094

Prati, G., & Pietrantoni, L. (2009). Optimism, social support, and coping strategies as factors contributing to posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 14, 364–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325020902724271

Rueda, S., Mitra, S., Chen, S., Gogolishvili, D., & Globerman, J. (2016). Examining the associations between HIV-related stigma and health outcomes in people living with HIV/AIDS: A series of meta-analyses. BMJ Open, 6(7), e011453.

Rzeszutek, M., Oniszczenko, W., & Firląg-Burkacka, E. (2016). Gender differences in posttraumatic stress symptoms and the level of posttraumatic growth among a Polish sample of HIV-positive individuals. AIDS Care: Psychological, and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV, 28, 1411–1415. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2016.1182615

Rzeszutek, M., Oniszczenko, W., & Firląg-Burkacka, E. (2017). Social support, stress coping strategies, resilience and posttraumatic growth in a Polish sample of HIV+ individuals: Results of a one-year longitudinal study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 40, 942–954. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-017-9861-

Rzeszutek, M., & Gruszczyńska, E. (2018). Posttraumatic growth among people living with HIV: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Review, 114, 81–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.09.006

Sawyer, A., Ayers, S., & Field, A. P. (2010). Posttraumatic growth and adjustment among individuals with cancer and HIV/AIDS: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 30, 436–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2010.02.004

Schwarzer, R., Luszczynska, A., Boehmer, S., Tauber, S., & Knoll, N. (2006). Changes in finding benefit after cancer surgery and the prediction of well-being one year later. Social Science and Medicine, 63, 1614–1624. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.004

Shakespeare-Finch, J., & Lurie-Beck, J. (2014). A meta-analytic clarification of the relationship between posttraumatic growth and symptoms of posttraumatic distress disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28, 223–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.10.005

Sears, S., Stanton, L., & Danoff-Burg, S. (2003). The yellow brick road and the emerald city: Benefit finding, positive reappraisal coping, and posttraumatic growth in women with early-stage breast cancer. Health Psychology, 22, 487–497. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.487

Seligman, M., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2000). Positive psychology. An introduction. American Psychologist, 55, 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Sherr, L., Nagra, N., Kulubya, G., Catalan, J., Clucasa, C., & Harding, R. (2011). HIV infection associated post-traumatic stress disorder and post-traumatic growth—A systematic review. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 16, 612–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2011.579991

Siegel, K., Schrimshaw, E., & Pretter, S. (2005). Stress-related growth among women living with HIV/AIDS: Examination of an explanatory model. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 28, 403–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10865-005-9015-6

Taku, K., Tedeschi, R. G., Shakespeare-Finch, J., Krosch, D., David, G., Kehl, D., Grunwald, S., Romeo, A., Di Tella, M., Kamibeppu, K., Soejima, T., Hiraki, K., Volgin, R., Dhakal, S., Zięba, M., Ramos, C., Nunes, R., Leal, I., Gouveia, P., & Calhoun, L. (2020). Posttraumatic growth (PTG) and posttraumatic depreciation (PTD) across ten countries: Global validation of the PTG-PTD theoretical model. Personality and Individual Differences. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110222 Advance Online Publication.

Tedeschi, R., & Calhoun, L. (1996). The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9, 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490090305

Tedeschi, R., & Calhoun, L. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli150101

Tedeschi, R. G., & Kilmer, R. P. (2005). Assessing strengths, resilience, and growth to guide clinical interventions. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 36, 230–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.36.3.230

Tedeschi, R., Shakespeare-Finch, J., Taku, K., & Calhoun, L. (2018). Posttraumatic growth theory, research, and applications. Routledge.

Tennen, H., & Affleck, G. (2009). Assessing positive life change: In search of meticulous methods. In C. L. Park, S. C. Lechner, M. H. Antoni, & A. L. Stanton (Eds.), Medical illness and positive life change: Can crisis lead to personal transformation? (pp. 31–49). American Psychological Association.

Vishnevsky, T., Cann, A., Calhoun, L., Tedeschi, R., & Demakis, J. (2010). Gender differences in self-reported posttraumatic growth: A meta-analysis. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 34, 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.2009.01546.x

Waugh, C., Shing, E., & Furr, R. (2020). Not all disengagement coping strategies are created equal: Positive distraction, but not avoidance, can be an adaptive coping strategy for chronic life stressors. Anxiety, Stress, and Coping, 33, 511–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2020.1755820

Ye, Z., Xiaonan, N., Yu, W., Chen, L., & Lin, D. (2017). A randomized controlled trial to enhance coping and posttraumatic growth and decrease posttraumatic stress disorder in HIV-Infected men who have sex with men in Beijing, China. AIDS Care, 18, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2017.1417534

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The corresponding author declares that he has no conflict of interest. The second author declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Rzeszutek, M., Gruszczyńska, E. Trajectories of Posttraumatic Growth Following HIV Infection: Does One PTG Pattern Exist?. J Happiness Stud 23, 1653–1668 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00467-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-021-00467-1