Abstract

Numerous studies document that societal happiness is correlated with individualism, but the nature of this phenomenon remains understudied. In the current paper, we address this gap and test the reasoning that individualism correlates with societal happiness because the most common measure of societal happiness (i.e., country-level aggregates of personal life satisfaction) is individualism-themed. With the data collected from 13,009 participants across fifty countries, we compare associations of four types of happiness (out of which three are more collectivism-themed than personal life satisfaction) with two different measures of individualism. We replicated previous findings by demonstrating that societal happiness measured as country-level aggregate of personal life satisfaction is correlated with individualism. Importantly though, we also found that the country-level aggregates of the collectivism-themed measures of happiness do not tend to be significantly correlated with individualism. Implications for happiness studies and for policy makers are signaled.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Many studies have demonstrated that societal happiness, measured as country-level average of personal life satisfaction, correlates with national levels of individualism (Diener et al. 1995; Hofstede 2001; Krys et al. 2019b; Steel et al. 2018). However, the nature of this association remains understudied. The purpose of this study is to explore details of this association as proposed by Krys et al. (2019c), viz., that the reason why individualism is associated with societal happiness is that the most common measure of societal happiness (i.e., personal life satisfaction) is individualism-themed. To do so, we measured more collectivism-themed types of happiness (e.g., family interdependent happiness) across fifty countries, and demonstrate that some of these more collectivism-themed types of societal happiness are not predicted by individualism, but by other features of national culture. In doing so, this study extends the current discussion on potential antecedents of societal happiness by showing that individualism is a pathway to one type of happiness only; there are other cultural pathways to other types of happiness.

2 Societal Happiness and Individualism

Numerous large cross-country studies have documented that societal happiness is predicted by individualism—above and beyond other social, economic and cultural factors characterizing societies (Diener et al. 1995; Hofstede 2001; Krys et al. 2019b; Kuppens et al. 2008; Jasielska et al. 2018). These consistent findings led Oyserman et al. (2002) to conclude that “individualism may increase well-being” (p.42). More recently Krys et al. (2019b) described the mechanism that may be responsible for the causality proposed by Oyserman and collaborators. They showed that individualism promotes societal happiness if it adopts the form of the open society. Four attitude orientations constituting open society: (1) tolerance, (2) trust, (3) civic engagement, and (4) non-materialism tend to benefit society as a whole, but do not directly and substantially promote individual satisfaction. Individuals endorsing open society attitudes are not considerably more satisfied than prejudiced, suspicious, uninvolved, and materialistic members of the same society, but societies in which open society attitudes are prevalent report greater happiness than closed societies.

Much of the evidence linking individualism with societal happiness (Diener et al. 1995; Hofstede 2001; Krys et al. 2019b; Kuppens et al. 2008; cf. Steel et al. 2018) is based on country-level averages of personal life satisfaction ratings from a society’s members, proposed by Diener et al. (1985). This kind of finding begs the question of whether other types of happiness, aggregated to societal level, are also correlated with individualism. In particular, it is important to learn whether the more collectivism-themed types of happiness are associated with societal individualism.

3 Collectivism-Themed Types of Happiness

Happiness is not a single-faceted phenomenon. Within and across cultures people conceptualize happiness differently (Delle Fave et al. 2016; Krys et al. 2019a, b; Kwan et al. 1997; Uchida and Kitayama 2009). Life satisfaction (Diener et al. 1985), for instance, originates from the so-called WEIRD academic tradition (Heinrich et al. 2010), and became the most popular conceptualization of happiness in psychological research (as of 2020, according to Scopus database, the Diener et al. 1985 paper has been cited over 10,000 times, which makes it one of the most influential papers in psychological science). Recent cross-cultural studies of well-being have introduced the concept of interdependent happiness (Hitokoto and Uchida 2015) as a more relationship-oriented view of happiness—emphasizing harmony with others, quiescence, and ordinariness. Interdependent happiness is supposed to be a prioritized goal for Confucian Asian cultural systems in particular, but in general is theorized to be pursued by people in other forms of collectivistic cultures as well (Mathews and Izquierdo 2008). Life satisfaction and interdependent happiness are partly overlapping (Krys et al. 2019c)—all types of happiness probably share a common core, but emphasize different aspects of happiness: interdependent happiness is more relationship-oriented and life satisfaction tends to be more achievement-oriented. Indeed, Uchida and Ogihara’s (2012) early review of literatures on cultural construals of happiness suggested that the common measures of happiness (e.g., Diener et al.’s life satisfaction) are based on European-American ideas of happiness that focus on personal achievement and attainment, which are less emphasized in collectivistic cultures (Lu and Gilmour 2006; Oishi 2010).

Another step towards understanding collectivism-themed types of happiness was made by Krys and collaborators (2019a, c). Krys and his collaborators have reported that the “basic unit of survival” differentiates individualism from collectivism—for individualism, it is individual person; in collectivism, it is a group (Hui and Triandis 1986). Thus, they proposed that one of the reasons why country-level aggregates of happiness appear to be correlated with cultural individualism is the fact that common measures of happiness focus on the individual person, the typical target of interest in research conducted in individualistic cultures (Sampson 1981). In order to lend initial support to their thesis, Krys et al. (2019c) carried out a study across twelve countries and found that family interdependent happiness is not significantly associated with individualistic cultures. Family interdependent happiness refers to the collective happiness of one’s family and the extent to which one’s family is in harmony with other families and groups in one’s community. Whereas interdependent happiness makes individuals the central evaluators of happiness of themselves and those around them, in family interdependent happiness families’ happiness is the target of interest. In the current paper we expand the Krys et al. (2019c) study to fifty countries.

From the outset, it is important to note the distinction between moderating roles of culture on people’s life evaluation as suggested in the literature and measurement issues the current study raises a question about. A previous study showed that people from collectivistic cultures are more influenced by social norms when evaluating their personal life satisfaction than those from individualistic cultures (Suh et al. 1998). On the other hand, our study focuses on a more basic matter about the way measures are constructed (i.e., where the items focus when asking individuals about their life).

4 Reasoning Behind the Present Study

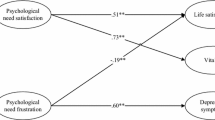

In the current study we test whether the association between happiness and individualism generalizes from personal life satisfaction to more collectivism-themed types of happiness. As with Krys et al. (2019c), we analyze four different types of happiness (see Fig. 1) emerging from combining two concepts of happiness (life satisfaction vs. interdependent happiness) with two targets of happiness (personal happiness vs. family happiness). This approach provides the opportunity to compare individualism-themed happiness (i.e., personal life satisfaction) with collectivism-themed happiness (e.g., interdependent happiness of family).

As with Krys et al. (2019c), we used the country-level aggregates of self-construals as a differentiated measure of individualistic-collectivistic cultural context. Self-construal theory (Markus and Kitayama 1991) proposed that culture-level phenomenon of individualism and collectivism can be “translated” into individual-level phenomenon of independent and interdependent self-construals, respectively. Measures of independent versus interdependent self-construals and individualism versus collectivism have often been treated as interchangeable (e.g., Effron et al. 2018; Oyserman et al. 2002). Accordingly, Krys, Zelenski and collaborators relied on Singelis’ (1994) scale to measure independent and interdependent self-construals, but here we turned to the more differentiated scale of self-construals proposed by Vignoles et al. (2016).

Vignoles et al. (2016) distinguished seven domains of self-construals that were previously confounded within commonly used measures of independence and interdependence, such as Singelis’ (1994) scale. According to the findings of Vignoles and collaborators, selves may be construed in terms of distinguishing the self (i.e., difference vs. similarity), experiencing the self (i.e., self-containment vs. connection to others), making decisions (i.e., self-direction vs. receptiveness to influence), looking after oneself (i.e., self-reliance vs. dependence on others), moving between contexts (i.e., consistency vs. variability), communicating with others (i.e., self-expression vs. harmony), or dealing with conflicting interests (i.e., self-interest vs. commitment to others). Recently, Vignoles (personal communication) proposed to add another aspect of defining the self: importance of context (i.e., decontextualized vs. contextualized self). Thus, in our study we check how each of these eight dimensions of self-construal—seven from Vignoles et al. (2016) original study and one additional recently proposed by Vignoles—correlates with each of four types of happiness.

After the launch of data collection, we learned that country-level aggregates of self-construals are not proxies of individualism-collectivism. Self-construal theory was built on the comparison of Confucian collectivism with North-American and Western-European individualism, and was commonly assumed to be valid for all types of collectivism. However, empirical evidence for self-construal theory hardly reaches beyond the two cultural macro-groups of this theory’s origin. In contrast, several large cross-cultural comparisons have documented that Latin Americans—members of template collectivistic cultures—describe their selfhoods as predominantly independent (Church et al. 2012; Krys et al. 2019c; Vignoles et al. 2016). This finding can be explained based on several different cultural characteristics [e.g., cultures of honor (Nisbett and Cohen 1996), endorsement of the maximization principle (Hornsey et al. 2018), or relational mobility (Thomson et al. 2018)]. Thus, in order to avoid potential pitfalls arising from inadequacy of using self-construals as a proxy of individualism-collectivism, in the present study we also included external measures of individualism-collectivism (Hofstede 2001; Minkov et al. 2017; Schwartz 2008).

Thus, the current study aimed to replicate and extend the results provided by Krys et al. (2019c). The substantial improvement in comparison to the original Krys, Zelenski et al. study comes from the increased complexity of the study presented here. First, we covered fifty countries, whereas Krys, Zelenski et al. collected data across twelve countries ‘only’. The large number of countries in the current study lessens the impact of potential bias arising from the limited number of countries in the previous research; the current analyses are based on completely new data as compared to Krys, Zelenski et al. original study, although all 12 countries from the original study were also covered by the current research project. Second, to study self-construals we employed a measure of high psychometric quality, providing a much more fine-grained picture on self-construals than the original Krys, Zelenski et al. study (i.e., Vignoles et al. vs. Singelis self-construal scales, respectively). Thus, with the current study, several important doubts arising from the original Krys, Zelenski et al. research may be resolved, and their conclusions, if confirmed, may be strengthened.

5 Method

The current study, was part of a larger cross-cultural investigation of the cultural factors related to happinessFootnote 1 (e.g., societal emotional environment, family happiness, and the valuation of different types of happiness). In the current paper, we focus on levels of four types of happiness and on eight dimensions of self-construal.

5.1 Participants and Countries

At the time of writing, our data set contained 13,009 participants from 50 countries: Argentina, Austria, Australia, Brazil, Bhutan, Bulgaria, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Croatia, Czech Republic, El Salvador, Estonia, France, Georgia, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, Indonesia, Iran, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malaysia, Mexico, the Netherlands, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Slovakia, Switzerland, Taiwan, Turkey, UK, Ukraine, and USA.

We aimed to recruit 200 individuals in each country. Some authors, however, collected more and others collected fewer. Overall, 59.6% of participants identified as female, 39.3% as male, 0.4% as other, and 0.7% left the question about gender blank; the mean age of participants was 25.18 years (SD = 9.51). We mainly collected samples of post-secondary students, but some authors managed to complement their student sample with a general population sample. Supplementary online material contains demographic characteristics by country, means and standard deviations of analyzed variables, as well as items and reliabilities of the scales used in this study.

5.2 Materials and Procedure

5.2.1 Levels of Four Types of Happiness: Own Data

We used the Satisfaction with Life Scale (personal SWLS; 5 items; Diener et al. 1985; e.g., You are satisfied with your life; α = .85 for the whole sample, in every country α > .70) to measure actual personal life satisfaction. The Interdependent Happiness Scale (personal IHS; 9 items; Hitokoto and Uchida 2015; e.g., You can do what you want without causing problems for other people; α = .87 for the whole sample, in every country α > .74) was used to measure the actual personal interdependent happiness. As in Krys and collaborators (Krys et al. 2019a, c), we also adapted both measures to assess participants’ views of their family’s happiness by changing the subject of the personal SWLS and personal IHS measures from the individual to their family (e.g., Your family is satisfied with its life for family SWLS; α = .90 for the whole sample, in every country α > .79, and As a family you can do what you want without causing problems for other people for family IHS; α = .91 for the whole sample, in every country α > .87). See supplementary online material for a full list of the original and modified SWLS and IHS items. Following Vignoles et al.’s (2016) approach, participants rated items of happiness and self-construal scales (see below) on a nine-point Likert-type scale with five labelled points: 1 (doesn’t describe me at all), 3 (describes me a little), 5 (describes me moderately), 7 (describes me very well), 9 (describes me exactly).

5.2.2 Self-construals as Markers of Individualistic-Collectivistic Context: Own Data

As a proxy of individualism-collectivism, we used the latest upgraded version of the Vignoles et al. (2016) self-construal scales. Originally, this scale contained seven dimensions: difference vs. similarity (6 items; e.g., You like being different from other people vs. You like being similar to other people; α = .76 for the whole sample, in each country apart from IndonesiaFootnote 2α > .58), self-containment vs. connectedness to others (6 items; e.g., You would not feel personally insulted if someone insulted a member of your family vs. If someone insults a member of your family, you feel as if you have been insulted personally; α = .72 for the whole sample, in forty-five countries2 α > .60), self-direction vs. receptiveness to influence (6 items; e.g., You usually decide on your own actions, rather than follow others’ expectations vs. You usually do what people expect of you, rather than decide for yourself what to do; α = .76 for the whole sample, in every country2 α > .55), self-reliance vs. dependence on others (6 items; e.g., You try to avoid being reliant on others vs. Being able to depend on others is very important to you; α = .78 for the whole sample, in every country2 α > .53), consistency vs. variability (6 items; e.g., You behave in a similar way at home and in public vs. You behave differently when you are with different people; α = .84 for the whole sample, in every country2 α > .66), self-expression vs. harmony (6 items; e.g., You like to discuss your own ideas, even if it might sometimes upset the people around you vs. You try to adapt to people around you, even if it means hiding your feelings; α = .76 for the whole sample, in every country2 α > .55), and self-interest vs. commitment to others (6 items; e.g., You protect your own interests, even if it might sometimes disrupt your family relationships vs. You usually give priority to others, before yourself; α = .69 for the whole sample, in every country2 α > .49). The upgraded version of the Vignoles scale included one additional dimension obtained from the first author of the scale (Vignoles, personal communication): de-contextualized vs. contextualized self (6 items; e.g., Someone could understand who you are without needing to know which social groups you belong to vs. If someone wants to understand who you are, they would need to know which social groups you belong to; α = .74 for the whole sample, in every country2 apart from Saudi Arabia α > .54). For full tables with reliabilities, please see supplementary material.

5.2.3 Individualism-Collectivism Meta-Factor: External Data

During data collection we learned that self-construals are not an ideal proxy of individualism-collectivism. Therefore in the analysis we also included an individualism-collectivism meta-factor extracted from individualism-collectivism measures offered by Hofstede (2001) and Minkov et al. (2017), and from autonomy-embeddedness measures that are reflecting individualism-collectivism in the value taxonomy of cultures offered by Schwartz (2008). We calculated an individualism-collectivism meta-factor by averaging standardized scores for each of these three datasets (α > .86).

5.3 Analytic Approach

We used two complementary analytic approaches: country-level correlational analysis and multilevel modelling (MLM). These two approaches employ different dependent variables; country-level happiness for correlational analysis and individual-level happiness for MLM analysis. The purpose of this study is to study country-level associations between happiness and individualism; thus, we describe correlational analysis as the main analytic tool, and MLM as an additional analytic tool.

For the predicted variables, we analyzed the four types of happiness (i.e., personal SWLS, personal IHS, family SWLS, and family IHS). For predicting variables, we used eight dimensions of self-construals, and additionally, the individualism-collectivism meta-factor. When comparing country-level correlation coefficients, we employed the test of the difference between two dependent correlations with one variable in common (Steiger 1980).

In two-level analyses, self-construals served as individual-level predictors (this way we studied the influence of individual mindset on happiness), and country-level aggregates of self-construals served as country-level predictors (this way we studied the influence of cultural context on happiness). Furthermore, we controlled for cross-level interactions between individual mindset and cultural context, and for gender, age and social capital of participants (i.e., education of their parents) at the individual-level of analyses, and for GDP per capita at the country-level of analyses.

We employed in our analyses eight different dimensions of self-construal as predicting variables, and four different types of happiness as predicted variables. Thus, in total, we carried out thirty-two, different two-level analyses; each model with cross-level interactions and with random intercepts and slopes. For the more detailed description of our approach to two-level analyses (e.g., regarding centering decisions), please see the supplementary material.

6 Results

6.1 Correlational Analyses

6.1.1 Four Types of Happiness and Self-Construals

We present a summary of the country-level correlational results in Table 1. In line with previous studies on the relationship between individualism and societal happiness, personal SWLS was positively correlated with four facets of individualistic self-construals: self-expression, decontextualized self, self-direction and consistency (all ps < .003). Importantly, as predicted the association between societal happiness and these four individualistic contexts was attenuated when more collectivism-themed types of happiness were analyzed. For each of the four dimensions, the correlations with individualistic context were statistically higher for personal SWLS (the most individualism-themed measure of happiness) than for family IHS (the most collectivism-themed measures of happiness), zs > 2.09, ps < .037. In fact, family IHS did not significantly correlate with three of the four analyzed individualistic contexts, and in the case of decontextualized self the correlation was on the level of statistical trend only (p = .054).

In the case of the four other individualistic contexts of self-construals—self-reliance, difference, self-containment, and self-interest—their correlations with personal SWLS were not significant, nor were they significantly correlated with the other types of happiness.Footnote 3 When we compared the strength of these correlations, we found the pattern where personal SWLS was closer to individualistic context than family IHS (see subscripts in Table 1).

6.1.2 Four Types of Happiness and the Individualism-Collectivism Meta-Factor

As in numerous previous studies, we found a significant correlation between the individualism-collectivism meta-factor and country-level happiness measured as averaged personal SWLS, r(46) = .32, p = .026. However, correlations of the individualism-collectivism meta-factor with societal happiness measured as aggregates of other types of happiness did not reach statistical significance: r(46) = .24, p = .11 for personal IHS, r(46) = .10, p = .49 for family SWLS, and r(46) = .06, p = .69 for family IHS. Figure 2 presents a visual illustration of our findings. The direct comparison between correlation coefficients revealed significant differences for the personal SWLS and family IHS comparison (z = 2.24, p = .025), for the personal IHS and family IHS comparison (z = 1.97, p = .049), and for the personal SWLS and family SWLS comparison (z = 2.42, p = .016); other zs < 1.36 and ps > .17.

Correlation coefficients for individualism meta-factor and four types of happiness. Note. Whereas personal life satisfaction is the most individualism-themed measure of happiness and family interdependent happiness is the most collectivism-themed measure of happiness out of the four types of happiness we examined, family life satisfaction and personal interdependent happiness can be regarded as sharing qualities of both cultural contexts. Therefore, the arrangement of these two intermediate types of happiness is arbitrary and could be reversed. *p < .05; n.s.(not significant) means p > .10

6.2 Two-Level Analyses

For the MLM analyses, we employed the eight different dimensions of self-construals as predictor variables and four types of happiness as dependent variables (see supplementary online material, for the results of all thirty-two models). These analyses were generally consistent with the results of our main correlational analyses: culture-level aggregates of the four types of individualistic self-construals (i.e., self-expression, decontextualized self, self-direction and consistency) predicted personal life satisfaction (.005 < ps < .040), and not a single culture-level aggregate of individualistic self-construals significantly predicted family interdependent happiness (ps > .39).

7 Discussion

In this study, we sought to test whether four types of societal happiness can be predicted by societal individualism. We did so by collecting data across fifty different countries on four types of happiness—personal life satisfaction, personal interdependent happiness, family life satisfaction, and family interdependent happiness (for their taxonomy, see Fig. 1)—and then correlating them with two types of individualism measures: one based on dimensions of self-construals, and the other on external scores from Hofstede (2001), Minkov et al. (2017) and Schwartz (2008) that we aggregated into an individualism-collectivism meta-factor. Across both approaches, we replicated previous findings showing that societal happiness measured as country-level aggregate of personal life satisfaction was correlated with individualism. Importantly, both approaches also revealed that the country-level aggregates of the most collectivism-themed type of happiness (i.e., family interdependent happiness) was not significantly correlated with individualism.

This finding lends support to Krys et al. (2019c) reasoning that previous studies have found associations between individualism and societal happiness because they relied on an individualism-themed measure of happiness. In particular, personal life satisfaction focuses on the individual person as the subject of the measure and it is based on the concept of happiness that originated in so-called WEIRD societies (i.e., life satisfaction). In contrast, interdependent happiness is a concept of happiness that originated from studies in Confucian cultural contexts and is theorized to be pursued by collectivists everywhere. Given that the “basic unit of survival” in collectivistic cultures is a group (and not an individual; Hui and Triandis 1986), the pursuit of family happiness may be a relatively more important ideal than the pursuit of personal happiness (Krys et al. 2019a). Taken together, our findings show that the association between individualism and societal happiness, even if causal (Krys et al. 2019b; Oyserman et al. 2002), may be limited to an individualism-themed concept of happiness.

Interestingly, similar to Krys et al. (2019c), we did not find a significant positive correlation between collectivism and the most collectivism-themed measure of societal happiness (i.e., country-level aggregate of family interdependent happiness). In searching for the explanation to this finding, we propose to turn to cross-cultural variability in the valuation of happiness. The ideal level of happiness does not have to be the same across cultures—in some cultures, people may wish to maximize their happiness, whereas in others people may be content with moderate levels of happiness. Although cross-cultural studies on ideal levels of happiness are rare (cf. Hornsey et al. 2018), Diener signaled that people in individualistic cultures tend to grant happiness greater importance than do respondents in collectivistic cultures (Diener 2000; see p. 34). If so, in collectivistic cultures the collectivism-themed type of happiness may be pursued relatively more than the individualism-themed type of happiness, and at the same time happiness in general (in all its types) may be pursued less in collectivistic cultures than in individualistic cultures. These two cultural tendencies may result in the reported lack of positive correlation between collectivism-themed happiness and collectivism. Cross-cultural studies on the valuation of happiness are needed to test this proposed explanation. Furthermore, cross-cultural studies on the valuation of various types of well-being (i.e., not only happiness) are needed to better understand what serves as the “ultimate” type of well-being for collectivistic cultures.

Finally, it may be interesting (and novel in comparison to the Krys et al. 2019c study) that only four dimensions of self-construal were associated with individualism-themed types of societal happiness: self-expression, decontextualized self, self-direction, and consistency. Four other self-construal dimensions—self-interest, self-containment, self-reliance, and difference—turned out to not be correlated with individualism-themed societal happiness. To guide future research on this topic, we propose two possible post hoc explanations. First, further studies may test whether these four dimensions of self-construals are (un)reliable proxies of individualism-collectivism. Vignoles with collaborators already signaled that two of the four dimensions we indicated as not being associated with societal happiness were not related to individualism (self-reliance and self-interest; see Table 9 in Vignoles et al. 2016). This inconsistency might reinvigorate the discussion on what is individualism, and its consequences for societal well-being. Second, it may turn out that these four contexts of individualism-collectivism are not, in fact, associated with individualistic-themed societal happiness. The latter explanation would signal that not all facets of individualism are related to societal happiness and thus would bring a novel perspective on the association between individualism and societal happiness.

8 Implications for Well-Being Studies

Recent research on happiness has documented a variety of lay understandings of this concept across cultures (Delle Fave et al. 2016; Uchida and Kitayama 2009). The vast majority of this research is based on measures primarily designed to assess personal life satisfaction (e.g., Letki et al. 2019). Personal life satisfaction, although recognized across many cultures, may not be the sole motive and ultimate aim of human behavior—there may be other types of happiness that people may be driven to pursue more (as well as other types of well-being than happiness). For example, Krys et al. (2019a) showed that people value family happiness over personal happiness. Similarly, Hitokoto and Uchida (2015) theorized that in Confucian Asia people pursue interdependent happiness more than life satisfaction. All of this supports the conclusion that the inclusion of other measures of happiness will help advance toward a more culturally objective understanding of human happiness. Even if all concepts of happiness are overlapping and reinforce each other (which seems reasonable because they all may share a common core), it does not necessarily mean that they all share the same qualities. Here, we document that at the country-level of analysis individualism-themed and collectivism-themed types of happiness are differently correlated with individualism. Thus, more studies on antecedents and correlates of various types happiness are needed.

With our findings, we also provoke questions on the cross-cultural valuation of happiness and other types of well-being. Whereas it seems plausible that the vast majority of people across all cultures prefer being happy over being unhappy, the ideal level of happiness, from the cross-cultural perspective, remains unclear (Hornsey et al. 2018; Diener 2000; Krys et al. 2019a). In some cultures, people may wish to maximize their happiness, whereas in others moderate levels of happiness can be regarded as “good enough”. By documenting the cultural nature of various types of happiness, we also provoke the question on whether well-being is tantamount to happiness (cf. Delle Fave et al. 2016). From the perspective of cross-cultural psychology, it seems plausible that people across cultures may idealize various types of well-being (e.g., happiness, meaning, spirituality, harmony) to various extents. Empirical cross-cultural research on ideal levels of various types of well-being seems to be a promising avenue for well-being studies.

9 Implications for Policy Makers

Several recent discussions have opened up people’s minds to alternatives to GDP per capita as the primary measure of societal development (Stiglitz et al. 2009). The idea of measuring National Accounts of Well-being (NAWB; Diener et al. 2015) seems to be one of the leading options, and as of 2019 became adopted by several governments and large international organizations like the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (Durand 2018). The NAWB idea is an important step forward in terms of identifying post-economic pathways for societal development. For now, however, most NAWB frameworks are based on measuring societal happiness as aggregates of personal life satisfaction.Footnote 4 GDP per capita is correlated with individualism. In line with this argument, a recent study on societal-level well-being indicators suggests that (personal) life satisfaction is an indicator of socio-economic progress because it mainly focuses on external conditions of life such as education, economic quality and business environment (Joshanloo et al. 2019). Thus, by employing an individualism-themed measure of subjective well-being to provide the alternative to GDP per capita, we may not be able to avoid the GDP-centrism inherent in societal development measures. Frameworks for NAWB may need to utilize other well-being measures as well (e.g., happiness of families, sense of meaning in life, sense of harmony, sense of spirituality). This enlargement would allow well-being to be measured in a way that is less culture-bound, and offers a more culturally sensitive (or culturally objective) framework of the NAWB (Krys et al. 2020).

10 Limitations

Before conclusions are drawn, it is important to acknowledge several limitations of this study. First, the current study mainly relied on student samples—future studies should confirm the robustness of our findings among older participants. Second, our sampling of cultures, even if broad, was biased towards individualistic cultures—we acknowledge this limitation (but also signal that this is a problem in almost all large cross-cultural studies). Next, one of the measures of individualism-collectivism we employed (i.e., country-level aggregates of self-construals) needs to be treated with caution—recent studies show that it may be not a good proxy of individualism-collectivism. In addition, not all dimensions of self-construals turned out to be positively correlated with societal happiness measured by personal life satisfaction—this result indicates the need for further studies. Next, in several countries the reliabilities for the self-construal measures fell below conventional cut-off levels. As of 2020, Vignoles’ self-construal scales show the best psychometric qualities among available self-construal scales, but if better scales appear in the future, further studies may need to replicate our findings with these improved scales. Finally, we studied concepts of happiness originating from so-called WEIRD societies (i.e., life satisfaction) and from Confucian societies (i.e., interdependent happiness); research on indigenous concepts of happiness (and their association with individualism) for other cultural regions are needed.

11 Concluding Remarks

In the current study we document that the positive association of societal happiness—conceptualized as country-level aggregates of personal life satisfaction—with individualism should not be generalized to collectivism-themed types of happiness. The preliminary evidence supporting this claim was proposed by Krys et al. (2019c) who studied twelve countries. We provide further support in the current study with data collected across fifty countries, and with alternative proxies of cultural individualism. We anticipate that our findings will stimulate research into various types of happiness—in particular those that might help characterize happiness conceptualizations from regions currently under-represented in cross-cultural studies—Africa, Eastern Europe, Latin America, Middle East, and South Asia. With our study, we also call for more cultural sensitivity (or cultural objectivity) in designing national accounts of well-being—people around the world deserve policies that are informed by, and help them pursue, well-being in their local cultural context (Krys et al. 2020). Ultimately, there are many ways of conceptualizing and living a happy and good life, and they each deserve being acknowledged by psychological science.

Notes

The study was approved by the research ethics committee of the Institute of Psychology of the Polish Academy of Science (approval #7/11/2017). Additionally, in each country where local regulations require separate ERB approval, local teams obtained such approvals.

In the Indonesian sample, we found problematic reliabilities for every self-construal dimension. Therefore, Indonesian data are excluded from further analysis based on self-construal scales, and also are not covered by further information on reliabilities in the current section (i.e., for each further information on self-construal scale’s reliability the text should read “…in each country apart from Indonesia…”). For full set of reliabilities, including those in Indonesia, please see supplementary online material.

Apart from statistical tendency (p = .054) in the correlation between family SWLS and commitment, which was the only close to significant positive association between collectivistic context and societal happiness.

Durand (2018), in her report titled “Countries’ Experiences with Well-being and Happiness Metrics”, analyses national well-being measurement initiatives and indicators employed in twelve countries (see Table 2.1 in Durand 2018). Eight of nine countries that are reported as employing subjective well-being in their national well-being frameworks rely on personal life satisfaction (these are Austria, Belgium, Ecuador, Finland, Germany, Italy, Israel, Slovenia). The ninth country—Japan—asked its citizens to simply rate “happiness”. Interestingly, the only country that reached beyond hedonic and emotional aspects of subjective well-being is Ecuador—a template collectivistic country—in which national well-being also covers spirituality and eudaimonia.

References

Church, T., Alvarez, J. M., Katigbak, M. S., Mastor, K. A., Cabrera, H. F., Tanaka-Matsumi, J., et al. (2012). Self-concept consistency and short-term stability in eight cultures. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 556–570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2012.06.003.

Delle Fave, A., Brdar, I., Wissing, M., Araujo, U., Castro Solano, A., Freire, T., et al. (2016). Lay definitions of happiness across nations: The primacy of inner harmony and relational connectedness. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00030.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.34.

Diener, E., Diener, M., & Diener, C. (1995). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 851–864. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.851.

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa490113.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. (2015). National accounts of well-being. American Psychologist, 70, 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038899.

Durand, M. (2018). Countries’ experiences with well-being and happiness metrics. The global happiness council (2018) (pp. 200–246). New York: Sustainable Development Solutions Network.

Effron, D. A., Markus, H., Jackman, L., Muramoto, Y., & Muluk, H. (2018). Hypocrisy and culture: Failing to practice what you preach receives harsher interpersonal reactions in independent (vs. interdependent) cultures. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.12.009.

Heinrich, J., Heine, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0140525x0999152x.

Hitokoto, H., & Uchida, Y. (2015). Interdependent happiness: Theoretical importance and measurement validity. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 211–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9505-8.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hornsey, M., Bain, P., Harris, E., Lebedeva, N., Kashima, E., Guan, Y., et al. (2018). How much is enough in a perfect world? Cultural variation in ideal levels of happiness, pleasure, freedom, health, self-esteem, longevity, and intelligence. Psychological Science, 29, 1393–1404. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618768058.

Hui, C. H., & Triandis, H. C. (1986). Individualism-collectivism: A study of cross-cultural researchers. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 17, 225–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022002186017002006.

Jasielska, D., Stolarski, M., & Bilewicz, M. (2018). Biased, therefore unhappy: Disentangling the collectivism-happiness relationship globally. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49, 1227–1246. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022118784204.

Joshanloo, M., Jovanović, V., & Taylor, T. (2019). A multidimensional understanding of prosperity and well-being at country level: Data-driven explorations. PLoS ONE, 14, e0223221. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0223221.

Krys, K., Capaldi, C. A., Zelenski, J. M., Park, J., Nader, M., Kocimska-Zych, A., et al. (2019a). Family well-being is valued more than personal well-being: A four-country study. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00249-2.

Krys, K., Uchida, Y., Oishi, S., & Diener, E. (2019b). Open society fosters satisfaction: Explanation to why individualism associates with country level measures of satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14, 768–778. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1557243.

Krys, K., Zelenski, J. M., Capaldi, C. A., Park, J., van Tilburg, W., van Osch, Y., et al. (2019c). Putting the “we” in well-being: Using a collectivism-themed measure of well-being attenuates well-being’s association with individualism. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 22, 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12364.

Krys, K., Capaldi, C. A., Lun, V. M.-Ch., Vauclair, Ch.-M., Bond, M. H., Domínguez-Espinosa, A., & Uchida, Y. (2020). Psychologizing indexes of societal progress: Accounting for cultural diversity in preferred developmental pathways. Culture & Psychology, 26, 303–319. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X19868146.

Kuppens, P., Realo, A., & Diener, E. (2008). The role of positive and negative emotions in life satisfaction judgment across nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.66.

Kwan, V., Bond, M., & Singelis, T. (1997). Pancultural explanations for life satisfaction: Adding relationship harmony to self-esteem. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 1038–1051. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.73.5.1038.

Letki, N., Toruńczyk-Ruiz, S., & Kukołowicz, P. (2019). The effects of neighbourhood disorder on life satisfaction of ethnic majority and minority group members: Evidence from 12 Central-Eastern European countries. Social Psychological Bulletin, 14, 1–24.

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2006). Individual-oriented and socially oriented cultural conceptions of subjective well-being: Conceptual analysis and scale development. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 9, 36–49. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1367-2223.2006.00183.x.

Markus, H. R., & Kitayama, S. (1991). Culture and the self: Implications for cognition, emotion, and motivation. Psychological Review, 98, 224–253. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.98.2.224.

Mathews, G., & Izquierdo, C. (Eds.). (2008). Pursuits of happiness: Well-being in anthropological perspective. New York, NY: Berghahn.

Minkov, M., Dutt, P., Schachner, M., Morales, O., Sanchez, C., Jandosova, J., et al. (2017). “A revision of Hofstede’s individualism-collectivism dimension. Cross Cultural & Strategic Management, 24, 386–404. https://doi.org/10.1108/ccsm-11-2016-0197.

Nisbett, R. E., & Cohen, D. (1996). Culture of honor: The psychology of violence in the South. Colorado: Westview Press Inc.

Oishi, S. (2010). The psychology of residential mobility: Implications for the self, social relationships, and well-being. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5, 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691609356781.

Oyserman, D., Coon, H., & Kemmelmeier, M. (2002). Rethinking individualism and collectivism: Evaluation of theoretical assumptions and meta-analyses. Psychological Bulletin, 128, 3–72. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.128.1.3.

Sampson, E. E. (1981). Cognitive psychology as ideology. American Psychologist, 36, 730–743.

Schwartz, S. (2008). The 7 Schwartz cultural value orientation scores for 80 countries. Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/304715744_The_7_Schwartz_cultural_value_orientation_scores_for_80_countries. https://doi.org/10.13140/rg.2.1.3313.3040.

Singelis, T. (1994). The measurement of independent and interdependent self-construals. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20, 580–591. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205014.

Steel, P., Taras, V., Uggerslev, K., & Bosco, F. (2018). The happy culture: A theoretical, meta-analytic, and empirical review of the relationship between culture and wealth and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22, 128–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868317721372.

Steiger, J. (1980). Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 87, 245–251. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.87.2.245.

Stiglitz, J., Sen, A. K., & Fitoussi, J. P. (2009). The measurement of economic performance and social progress revisited: Reflections and overview. OFCE. https://hal-sciencespo.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01069384. Retrieved November 26, 2019.

Suh, E., Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Triandis, H. C. (1998). The shifting basis of life satisfaction judgments across cultures: Emotions versus norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.482.

Thomson, R., Yuki, M., Talhelm, T., Schug, J., Kito, M., Ayanian, A. H., et al. (2018). Relational mobility predicts social behaviors in 39 countries and is tied to historical farming and threat. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115, 7521–7526. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1713191115.

Uchida, Y., & Kitayama, S. (2009). Happiness and unhappiness in east and west: Themes and variations. Emotion, 9, 441–456. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015634.

Uchida, Y., & Ogihara, Y. (2012). Personal or interpersonal construal of happiness: A cultural psychological perspective. International Journal of Wellbeing, 2, 354–369. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v2.i4.5.

Vignoles, V., Owe, E., Becker, M., Smith, P., Easterbrook, M., Brown, R., et al. (2016). Beyond the ‘East-West’ dichotomy: Global variation in cultural models of selfhood. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 145, 966–1000. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge00001.

Funding

This work was supported by the Polish National Science Centre under Grant 2016/23/D/HS6/02946; the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science under Grants P17806 and 17F17806; the Hungarian OTKA under Grant K-111 789; the Brazilian National Council for Research—CNPq under Grant PQ301298/2018-1; the Czech Science Foundation under grant 20-08583S; the Shota Rustaveli National Science Foundation of Georgia under grant number YS 17–43; the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant 71873133; and the Department of educational studies, University of Roma Tre under biannual Grant DSF 2017-2018.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Krys, K., Park, J., Kocimska-Zych, A. et al. Personal Life Satisfaction as a Measure of Societal Happiness is an Individualistic Presumption: Evidence from Fifty Countries. J Happiness Stud 22, 2197–2214 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00311-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00311-y