Abstract

The claim that most people are happy and satisfied, assuming that high self-ratings on numerical scales indicate good lives, is cross-checked against extensive verbal reports in a large-scale mixed-methods validation study. For a sample of 500 qualitative interviews conducted in Austria, the usual 10-point-scale self-ratings of life satisfaction and happiness were linked to the content of respondents’ actual narrations. Additionally, the narrated well-being was classified according to an alternative evaluation scheme by external raters. The results show that many persons report substantial restrictions to their hedonic experience in spite of high or even very high ratings, and that the narrated well-being evaluation is much more critical than the self-rating. Therefore it is argued that a naïve interpretation of high self-rating values as top life experience systematically ignores negative aspects of life. The claimed predominance of happiness should be substantially reformulated. In particular, more attention should be drawn to resilient satisfaction in the presence of substantial psychological burden, and to the non-negligible group of highly positive life satisfaction ratings which lack evidence of corresponding hedonic experience in the life narratives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

It is a common statement in the subjective well-being (SWB) literature that most people in Western civilization feel happy and are satisfied with their lives. As an example of corresponding media coverage, Statistics Austria (2012) published in a press release that 79 % of the Austrians are satisfied with their lives, and reported a “high global life satisfaction”. Diener and Diener (1996) use the phrase “Most people are happy” as the title for a widely cited article. Indeed, there is a huge amount of data showing that country averages of life satisfaction (LS) ratings are mostly in the positive regions, seldom falling below “the midpoint of the scale” or the “neutral point” (p. 181): “For moods and emotions, the neutral point refers to that place at which the individual experiences an equal amount of pleasant and unpleasant affect. A positive hedonic level refers to experiencing positive affect more of the time than negative affect.” There is also evidence that people spend more time in predominantly positive hedonic states. In a similar vein, Veenhoven (1991) argues that reported levels of happiness are more than just relative values. However, Biswas-Diener et al. (2005: 205) conclude: “Thus, the fact that most people tend to be moderately happy does not mean that they are ecstatic.” Considering certain kinds of positivity tendencies in the ratings, they add later (223): “In other words, positive happiness ratings do not indicate that conditions are excellent or that the society need not be improved.” Indeed, other sources of evidence about psychological states seem to convey a less optimistic impression than satisfaction charts. As an example, prevalence of mental disorders in the past year is estimated as high as 27 % in the European Union (WHO 2015) and 19 % in the US (NIH 2015).

Cummins and Nistico (2002: 37) suspect a positive cognitive bias underlying the “remarkable level of uniformity” regarding self-rated SWB, which they specifically attribute to a necessity of keeping up self-esteem, control and optimism. Cummins (2003) and Tomyn and Cummins (2011) assume a general tendency of homeostatically protecting one’s own mood inhibiting negative thoughts about one’s life. Comparing the shape of different distributions, the former author concludes that homeostatic protection particularly prevents self-ratings falling below 70 % of the maximum possible value. This theory refers to LS in general, whereby the articles do not explicitly focus on biases only due to defense in the moment of responding. Similarly, Staudinger (2000) formulates high satisfaction in spite of negative circumstances as a “subjective well-being paradox”, and explains it, above all, by means of coping and adaptation processes (see also Shmotkin 2005).

Unfortunately, in spite of the complex and subjective character of LS and happiness, there are hardly any cross-checks at an individual level on what kind of lives and concrete circumstances are actually represented by numerical self-ratings such as 7 or 8, nor is there—to the authors’ knowledge—any guideline on how to translate an “8” back into actual life circumstances. This study tries to bridge this gap by comparing the self-ratings of 500 interview partners with the contents of in-depth semi-structured qualitative interviews about their lives.

1.1 Background

Measures of SWB (Diener 2000), in particular the aspects of LS (the overall evaluation of life satisfaction) and happiness (focusing rather on the emotional aspect), are widely used and have made their way into official statistics and reporting (Krueger and Stone 2014), such as the OECD publication “How’s life?” (OECD 2013a). Many see SWB-assessment as one of the tools which will enable a move away from the merely economic evaluation of societies (such as through GDP) towards a more human-centered view: In his seminal paper, Easterlin (1974) claims that LS remains rather static in spite of rapidly growing economic output, giving a diagnosis which is still subject to scientific debate (Stevenson and Wolfers 2008; Easterlin et al. 2010; Veenhoven and Vergunst 2014). Among others, the well-known “Stiglitz report” (Stiglitz et al. 2010) propose enhancing assessment of the progress of societies by including subjective indicators about well-being such as LS or happiness—a recommendation which has been widely adopted by many nations and international initiatives like Europe’s ‘Beyond GDP’ movement (European Commission 2015). However, there is still an ongoing discussion about the significance of subjective information in general, and about the meaning of LS or happiness ratings in particular (Angner 2005; Haybron 2008; Schwarz et al. 2008).

Formulations of items can be found in the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven 1995); the wording “Taking all things together, how satisfied are you with your life these days? 0…very dissatisfied, 10… very satisfied.” may serve as a typical example. Items of this kind reach a certain level of stability (Diener et al. 2013; see also Krueger and Schkade 2008)—correlations between two time points of about 0.56 (Fujita and Diener 2005), 0.67 (Michalos and Kahlke 2010) or 0.77 (Lucas et al. 1996) after 1 year—and validity—typically moderate correlations with plausible criteria of a satisfactory life (Diener et al. 2013; Larsen et al. 1985; Layard 2010; Oswald and Wu 2010). Critics refer to the fundamental problem that a rating about one’s own life involves many hardly controllable factors, such as different aspiration levels of what constitutes a “satisfying” life. For an overview about different interpretations of responses on LS questions see Haybron (2008).

Of course, although single-item measures are widely applied, far more sophisticated measurement tools have been developed, for example the Satisfaction with Life Scale (Diener et al. 1985) or panel approaches such as the experience-sampling method (Kahneman and Krueger 2006). However, the problems presented by this article still remain as long as the assessment is based on sets of items involving self-rating procedures.

In addition to the problem that measured LS may be subject to a lot of moderating processes, such as adaptation towards positive or negative changes in life, homeostatically protected mood (Tomyn and Cummins 2011), self-serving biases and top-down effects such as downgrading actual negative experience in global hindsight (cf. Diener et al. 2013), defense mechanisms, social desirability, different judgment standards, better-than-average-effects (Alicke 1985), context or order effects, and similar (for an overview, cf. Pavot 2008; OECD 2013b; Diener et al. 2013), we want to draw attention to two very fundamental measurement issues: the actual semantic meaning of “life satisfaction” from the respondent’s point of view, and the actual semantic meaning of the particular response categories. Interpreting the notion “life satisfaction” and the meaning of the possible response levels is typically left to the respondent. Whereas there are sophisticated scientific definitions describing how researchers understand “satisfaction”, the responses are usually just defined by their numerical positions between two extremes, for example a certain position between 0 and 10. Veenhoven (2009) had participants from various countries assign numbers from 0 to 10 to various verbal labels (in their respective languages) to indicate the level of implied happiness. Slight country differences were observed, such as “very happy” receiving an average rating of 9.0 from the Dutch, but 8.6 from the English participants. Even if all categories have a verbal anchor, formulations such as “very satisfied” leave still some room for interpretation. For a discussion about interpretation in rating scales, see Schwarz et al. 2008. Diener et al. (2013) discuss potentially differential use of the underlying numerical value by different persons, and how this might be dealt with by robustness analyses or mixed item-response models.

Well-known approaches to tackling the latter issue are the Cantril ladder (1965), which invokes a comparison with the “best possible life”, or the usage of anchor vignettes (King et al. 2004) where the respondents rate certain fictitious lives for satisfaction, enabling comparison of their own lives with the anchors. Neither approach assigns direct explanations for the absolute quality of a rated level; it still has to be taken as an implicit assumption that the respondents perceive the question and the grading of possible responses in a similar way to the professionals. In contrast, instruments like Kahneman’s and Krueger’s U-Index (Kahneman and Krueger 2006) circumvent the anchor problem by reporting a time percentage (namely, the time spent in a more unpleasant than pleasant state).

The aforementioned conclusion that most people are happy is subject to essentially the same problem: what amount (or ‘what level’) of happiness does it indicate? How happy is “happy”? Is the statement just another formulation of the numerical fact that average ratings are to the right of the middle of the scale, or does it express that most people really live in a desirable psychological state? The cited sources rather suggest that the latter is the case. In fact, interpreting values to the right of the middle as “happy” assumes that the respondent’s transition process (Kim-Prieto et al. 2005; ‘transformation function’ in Köke and Perino 2014) from life perception to self-rating and the researcher’s transformation function from the response back to a judgment of another person’s life are sufficiently inverse to each other (for an overview of the psychology of responding to rating scales, see again Schwarz et al. 2008; Schwarz and Strack 1999). In both cases, a semantic bridge between the rating and the experienced quality of life is desirable: either to give the term “happy” some psychological content, or to check whether people with responses in the upper half really enjoy a positive life experience.

Accordingly, the results described in the following will shed some more light on the actual meaning of happiness ratings, and in particular will provide evidence against premature interpretations of “very happy” responses as “top life experience”.

2 The MODUL Study of Living Conditions

Between April and August 2012, 500 semi-structured interviews were conducted in German language at 10 different locations in Austria (Ponocny et al. 2015). 27.6 % of respondents (all aged 16+) were recruited by simple random sampling from telephone lists, professional marketing address lists, and via local communities. The remaining participants were recruited through snowball sampling by the randomly sampled participants, whereby an additional 22.8 % stemmed from the same household, with the other 49.6 % from new households. Demographic data showed approximate representativeness of the Austrian adult population regarding age and education, but not for gender (62.1 % female). Respondents were asked about good and bad things in life by a total of 12 trained interviewers (psychology graduates), with a typical interview duration of about 45 min. The aim of the interviews was to cover those aspects which were important for the evaluation of life from the participant’s point of view. The interview guidelines contained, among others, the tasks “Describe good and bad times in your life”, “What is important for your well-being?”, “Are there burdens or challenges in your life?”, “What is currently influencing your mood?”, “Are there restrictions in your life?”, and at the end “Are there issues influential to your well-being which have not been addressed yet?” Almost all interviews took place in the interviewees’ homes and were audio-recorded and transcribed.

The guidelines for these semi-structured interviews had been probed and improved in pre-tests on 50 persons. Immediately after the interviews, a 1-page demographic questionnaire was filled in, which involved the standard questions “Taking all things together, how satisfied with your life/how happy are you these days?” (in German), with a 10-point rating between “very dissatisfied” and “very satisfied” or “very unhappy” and “very happy”, respectively. The 10-point scale was chosen in order to be consistent with the European Quality of Life Survey (Eurofound 2005). (The German terms were “zufrieden” for “satisfied” and “glücklich” for “happy”.) Presenting the self-rating questions after the interview made it likely that the responses coincide more closely to the contents of the narratives than the reverse order, which was desirable for the comparison between verbal and numerical statements.

The following results section links actual contents of life narratives to subjective self-ratings. An additional illustration is provided by a comparison between the self-ratings regarding happiness and LS and an alternative classification “narrated well-being” (NWB), for which a total of 13 raters coded their overall impression of the transcribed life narratives. NWB was developed in an iterative process of trial and error, merging theoretical expectations with empirical experience.

2.1 The NWB Classification

Since an interview contains manifold qualitative information which is hardly communicable in a journal paper, a classification scheme was developed in order to summarize the interviewees’ own evaluative judgments about positive and negative conditions of their lives. This scheme preserves information about whether considerable pleasure or displeasure was explicitly expressed by the participants, and provides a workable characterization of a person’s balance between these experiences. The different levels of the scheme are verbalized in a way which supports an interpretation of “how life is” in absolute terms, as independent of individual anchor levels as possible.

The starting point was the collection of good and bad circumstances. Numerical conversions like scaling or counting did not lead to satisfying consistency between different coders, but experience showed that explicitly considering the authenticity of emotional expression helped resolve discrepancies between different ratings. Similarly, explicitly involving coping efforts in the classification removed coding ambiguity substantially. In the end, a scheme with 11 different levels was considered detailed enough to assign all 500 cases plausibly, while retaining sufficient distinctiveness between the levels in terms of their semantic meaning. The resulting scheme is called the narrative well-being classification (NWB); an overview of its categories is given in Table 1.

Note that the NWB is not claimed to be an alternative assessment of life satisfaction or happiness, but an instrument to summarize the occurrence and affective balance of subjectively evaluated circumstances in a 45 min life narrative. Only aspects which influence present well-being are considered. It is a formative indicator (in the meaning of Diamantopoulos and Winklhofer 2001) rather than a reflective one, merging heterogeneous information into a single number, including objective and subjective aspects of well-being. But it is less quantitative than indexes proposed by Alkire and Foster (2011) which count the number of dimensions in which certain problematic thresholds are exceeded. Certainly, NWB cannot be considered as a fully objective external rating, but it does ease communication between researchers and is therefore employed as an illustration tool in the results section.

A substantial improvement regarding positive NWB ratings has been the consideration of “authentic” statements which go beyond mere (possibly dissonance-avoiding) evaluations (such as “my job is all right”) but make the appraisal plausible (such as “I love what I am doing at work”). Furthermore, the category “resilient happiness” (3) helped to classify persons who do well to a certain extent and plausibly describe their life experience as positive although life burdens them, which means that some life circumstances are described as unfavorable but the negative effects are largely overcome by successful coping. Typical examples are informal care-givers who tell about the burdens of their obligations but on the other hand credibly claim that they have adapted and do not mind anymore, or elderly people who change their activities according to their reduced capacities. This corresponds to “adaptation” in Zapf’s (1984) welfare positions—subjective well-being in spite of unfavorable objective conditions. Category (4) relates to similar situations in which the coping strategies are only partially successful. Three categories (5)–(7) (which are not considered ordered) characterize ambiguous narratives with no clear dominance of positive or negative aspects, yet are differentiated according to the degree of emotion expressed, whereby (7) includes interviews where people did not talk openly about their emotional experiences, for example by constantly downplaying them. (8) was introduced for situations where authentic positive experience reports are lacking, giving the impression of unfulfilled desires as the main impairment (cf. Zapf’s welfare position “dissonance”, dissatisfaction in spite of supportive objective conditions, or Mc Kennell’s 1978 “resigned”, satisfied but not happy). The remaining categories describe narratives with a clearly negative dominance, either still supported by (but outweighing) positive resources (9), or not (10), with (11) already describing symptoms of depression or naming it explicitly. According to the feedback during coding, these categories seem in principle workable, understandable, sufficiently distinct but nevertheless exhaustive.

The raters marked all circumstances with a reported evaluation and classified the degree of its influence on the interviewee’s life according to frequency and centrality (the detailed results are not reported here). All of these highlighted codes and the total interview content were eventually taken into account to assign a NWB rating. (A version of NWB suitable for self-rating is currently under preparation.)

It turned out that with sufficient training, inter-rater agreement increased to very satisfying levels: up to an intra-class-correlation of 0.85. (On the basis of two independent ratings per case, this would enable a Cronbach’s α reliability of 0.92, qualifying for as a highly reliable assessment.) The 500 codings which are used here rely on a platform where 12 raters reached an inter-rater agreement of 0.67, which is acceptable for our purposes (0.40–0.75 may be considered “fair to good”) (Fleiss 1986).

3 Results

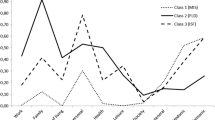

Figure 1 shows the distribution of the interviewees’ LS and happiness self-ratings which appear, as usual, to have a strong dominance of positive ratings (8.54 on average for LS, 8.46 for happiness) and a remarkable step between 7 and 8. The alternative NWB categorization, in contrast, suggests a much more moderate view (Fig. 2). There are substantially fewer extreme judgments, many more neutral categorizations, and more negative ones, though these remain a minority. Self- and external (where external coders rated life satisfaction and happiness on the basis of the interviews, using the same scale as the interviewee) standard numerical LS and happiness ratings on the 10-point rating scale are weakly related (Pearson’s r = 0.29, p < 0.001 for LS as well as for happiness), and external ratings are much more critical (on average: 7.71, p < 0.001, for LS, 7.43, p < 0.001, for happiness). There are, for LS, few cases (17 %) with a better external rating than an internal one, 27 % ties, but 56 % with more critical external ratings. (In particular, negativity bias in the meaning of Rozin and Royzman (2001) does not seem to play a dominating role.) The top LS categories 9 and 10 were chosen by 59.2 % of the self-raters, but only by 38.4 % of the external raters.

The small correlation between self- and external standard ratings cannot be explained purely by the information gap between real life and interview narrative, since external ratings of the same interviews by different coders are even less correlated (0.16 for LS, and 0.22 for happiness). Thus, there is a much lower degree of common understanding among the raters about how the standard scales should be applied to the narratives than for the NWB classification. But apart from this unsystematic variation, there remains a substantial systematic difference in the size of the values.

Thus, assuming that the interviews create a valid impression of a life at all, the ratings obviously do not mean the same to the subject and the observer (i.e. the transformation functions mentioned before are not inverse to each other). Additionally, in 24 % of cases the external raters judged the respondent’s value not to be plausible given the interview content. Extreme disparities could be found regarding dissatisfaction: 40 persons were rated 5 or worse by the external raters and 15 persons by self-rating, but of those only 6 cases match.

Table 2 shows the bivariate distribution of LS self-ratings and NWB (essentially the same picture is obtained for happiness, not shown). From the point of view of NWB, the “very satisfied” (LS) group looks rather heterogeneous, but not like a highly privileged one. Most interestingly, people who express only small emotions or who are categorized as “small emotions or close-lipped” have a strong tendency to rate themselves as “10”, which gives rise to the suspicion that, for some respondents, positive self-rating might express defensive response behavior rather than true bliss (in line with Cummins 2003, as mentioned in the introduction).

Some of the entries in Table 2 seem quite discrepant, combining rather negative NWB with very positive self-ratings, or, more seldom, the other way round. Fortunately, contents of the interviews offer some explanation. Two examples shall be given, one where the self-rating seems to characterize coping with unfavorable conditions rather than the actual hedonic status, and one which seems to involve cognitive reappraisal or suppression of emotional expression which are well-known strategies of emotion regulation (e.g. Gross 2002).

Regarding coping, a female participant (self-rating: 10) continuingly complains about the double burden of professional work and raising a small child, and was therefore rated as disharmonious life but with support: She “still regrets” becoming a mother again after an unplanned pregnancy, in particular missing the more comfortable life she was used to. She reports frequently being fully exhausted and flipping-out occasionally, but also that she appreciates the support by her husband and that she takes time for personal recreation every now and then, “when I can’t take it anymore and then say: Ok, I have to do something for myself, or I’ll flake out” (translated from German to English). In spite of all the social support, the case was not rated as “resilient” because the interviewee’s own words describe her actual emotional reaction to her situation as markedly negative.

The following passage from another interview reveals verbal compliance to obviously burdensome circumstances (self-rating: 9, NWB: disharmonious life but with support). Having repeatedly mentioned being burdened by time pressure, the participant responds to a question about restrictions in life: “Time pressure, I repeat myself […] It will get better. And still everything works. It does not knock me out. It is ok as it is. I just hope I continue to have the strength and health to keep going like that. And, all in all, it is fine. It is fine. [In German: “Es passt.”]” To what extent this can be taken as a direct proof of suppressed emotional expression is debatable, at any rate it strikingly demonstrates substantial (subjectively reported) impairment which is not detectable in evaluative judgments, verbally as well as numerically.

This case may also serve as an example of positive life satisfaction not considering current but rather temporary (or hopefully temporary) stressors, such as for students writing a thesis or persons longing for a partnership. In another example (self-rating: 9, NWB: small emotions or close-lipped), the interviewee insists his stressful experiences to be “normal”, which leads to a rationalization setting low standards: After claiming that stress at work influences his mood, he adds: “That’s normal, that does not matter”, and being asked whether this occurs often: “No, not really. But there are days, once a week, where it does. That’s normal. […] There is no job where you do all things right, where everything is ok. That does not exist. And if somebody says it does, he lies.”

In the very seldom cases where positive NWB meets very critical self-rating, the negative self-rating is harder to explain. One case shows a large discrepancy between LS (1) and happiness (9), maybe suggesting that—in spite of private happiness—she believes that her current job might only be a transition phase, making it too early to be “satisfied”. In another case (LS and happiness: 2, light-hearted happiness with minor impairment), the concept of happiness as an unreachable ideal leads to paradoxical statements (“if I would say I am happy I would most probably be very unhappy”). However, it is always possible that crucial issues have simply not been mentioned in the interview, or that persons occasionally mixed up the positive and the negative side of the response scales.

To explain why the NWB ratings have been so critical, Tables 3, 4 contrasts positive and negative life circumstances from the life narratives with self-rated LS values 7–10. Thereby, only life incidences enter the table for which the respondents themselves expressed substantial positive or negative hedonic consequences. Out of those, the most important ones for the person’s overall hedonic state as judged by the external raters were selected. The interviews were chosen according to implicit stratification by NWB (and randomly chosen within the strata) which is indicated on the left-hand side and by the background shades. Therefore the choice of cases can be regarded as representative for the LS categories within the sample. Tables 3, 4 clearly show that even extremely positive self-ratings do not necessarily indicate highly comfortable life circumstances or experiences, but may point to considerable harm or suffering. Even respondents with self-ratings of “10” often report substantial psychological burden, including financial restrictions, health problems, unemployment, alcoholism, discrimination, death or life-threatening diseases of close relatives, and sadness. With decreasing self-rating, the NWB rating also becomes more critical, as expected.

Aggregating NWB categories 1–2, 5–7, and 8–11, the same sample could be described following Fig. 3: 23 % of respondents are living an authentically happy life without major problems—light-hearted; 20 % are judged as resilient (coping well in spite of substantial psychological burden); another 15 % as noticeably impaired but still with positive tenor—still positive but impaired; a great proportion (28 %) seems rather balanced or close-lipped regarding positive and negative aspects; and finally for 15 % negative content seems to dominate the interview—negative balance. We believe that this is an informative, realistic and workable add-on to diagnoses like Fig. 1 or statements such as “84 % report one’s own LS of at least 8” or “the average LS is 8.54”.

What do these sample results tell us about the real-life meaning of the possible responses to the “life satisfaction” question? Table 2 suggests a rough translation of the rating scale values into the NWB scheme in the following manner: 10—“light-hearted with probably still some impairment, or possibly just close-lipped”; 8 and 9—“positive but impaired to a minor or substantial degree, resilient, or ups and downs balanced”; 7—“probably balanced, but could be more or less anything”. For the other infrequently chosen values, the sample is too small to reliably assign characteristics. The few cases with LS ratings of 5 or 6 generally show marked negative tendencies in NWB, as is the case for ratings of 4, but strangely not for ratings of 3 or worse.

4 Conclusion

Linking the interviews to LS or happiness self-ratings clearly shows that many persons evaluate their lives very positively, in spite of essential restrictions of their hedonic status (as narrated by themselves), an effect some researchers do not seem to be fully aware of (in particular according to feedback the authors received at conferences). Interpreting high self-ratings as representing highly pleasant psychological states would clearly underestimate the amount of suffering in the sample. Considering what people actually report in the interview, some high ratings seem mainly to express that their burden was not worse than normal, unbearable or as a reason to complain. Additionally, a considerable share of the cheerful self-evaluations is deemed implausible by external raters who obviously tend to apply different criteria than the interviewees themselves. Tables 3, 4 contain some examples of comments from high self-raters which appear contrary to what most people would consider a good life.

To sum up the results in the sample, good ratings should not be misinterpreted by researchers as indicating lives full of positive emotional experience, at least concerning some part of the population. Doing so will produce a positivity bias and artificially overestimate well-being. Contrasting the self-ratings with the NWB scheme, it becomes evident that only markedly positive ratings (8+) may be taken as clear dominance of positive over negative aspects, whereby also a part of these raters’ lives is substantially impaired.

In principle, these results allow for a wide range of different explanations: (1) A common understanding of the meaning of the numbers on the self-rating scales exists, but some of the well-known self-serving biases interfere when it comes to rating one’s own life. This view is supported by the fact that external raters evaluate systematically more critically than internal ones, and that many positive LS self-ratings lack plausibility. Moreover, the interviews contain lots of evidence of downplaying negative circumstances. In fact, this is observed in about half of the interviews (Grünwald 2014). (2) There is no self-serving bias and the numbers fully capture what people feel, but the external interpretation that “high rating = top life” is too superficial because the transformation processes life → self-rating (within the subjective rater) and self-rating → life (within the observing researcher) are not sufficiently inverse to each other. Evidence for this or similar views lies, for example, in the fact that some respondents explained LS (“Zufriedenheit” in German) as specific contentment with material or visible achievements (in contrast to the inner hedonic level), whereas others considered it just as a modest form of happiness (for these interviewees, highly rated satisfaction means that a basic happiness level is reached, but in no way indicates an extreme appraisal). A theoretical framework for the heterogeneity of happiness concepts across individuals is presented by Rojas (2005).

It has to be noted that the various interpretations do not necessarily affect SWB comparisons between groups or trend evaluations, but they strongly affect the interpretation of absolute levels, as reflected in statements such as “for most people, everything is ok”, or, that “most people are happy”. We believe that categorization schemes which better differentiate between the positive states possess higher relevance for policy. It could even be detrimental for a society’s progress if official institutions claim that a vast majority is doing well, as this may downplay the need for political action. Superficial pronouncements of a population’s well-being may therefore not only be useless but even dangerous.

Are most people happy, after all? Judged from our sample showing the usual positive self-ratings, a more sophisticated statement is required. Roughly speaking, comfortable experience seems to outweigh negative experience for a 60 %-majority (only). But it is also true that about 55 % seem noticeably impaired regarding their hedonic state. And of the more privileged remaining 45 %, almost half feel well in spite of substantial problems.

5 Limitations

These first results strongly suggest that quantitative ratings of SWB need to be evaluated and interpreted very carefully. Future studies need to confirm these findings, since the sample cannot be considered fully representative of the Austrian 16+ population, much less for populations in other countries. In particular, it cannot be concluded automatically that our results may be generalized to other languages than German, or to other cultures. Thus, the study cannot show how self-ratings work in general. On the other hand, there is no evidence that the relation between self-rating and life circumstances or the underlying psychological processes would be completely different for other countries (acknowledging that the translation of LS and happiness into national languages may create semantic differences).

The fundamental question arises as to whether it is at all possible to validate subjective life evaluation by external ratings of life narratives. Maybe an interview does not cover the really relevant aspects of life, or the emotional consequences of a narrated life are not accessible via external rating (moreover, the external ratings on the traditional 10-point scale could be negatively biased). Fortunately, there is empirical evidence that the discrepancy between NWB and self-rated LS does not merely reflect a principle impossibility of judging a life from outside: for example, in spite of the handicap of being evaluated by another person, NWB correlated even better to the self-rated item “living in harmony with oneself” (0.4) than the (also self-rated) LS (0.3). NWB does capture some aspects of subjective experience, but is far from being identical to the LS question—and should not be considered less relevant given the results in Tables 3, 4.

In any case, if a lengthy self-report should not provide the basis for a valid impression about a person’s hedonic state, it is also hard to assume that a few closed responses should. Note that our results do not at all question the honesty of the individual’s response, but rather any kind of naïve interpretation of the chosen rating value by an external observer.

Replication of these analyses in languages other than German or in different cultures would be highly recommendable, as well as additional applications of qualitative techniques or more sophisticated questionnaires, in order to better find out what respondents are actually telling us when they rate their lives.

6 Implications

How should SWB assessment improve, consequently? Further development in two directions is recommended: (1) SWB studies should involve more qualitative information to lay a more solid fundamental and validated basis for its assessment instruments, and (2) restricted inventories of question types should be avoided, by moving beyond overall evaluations of life or life domains to construct new items or response categories with more explicitly defined content. This approach would also be a step towards more person-oriented research in the meaning of Bergman and Magnusson (1997), acknowledging the importance of considering many components on the individual level simultaneously. In fact, the results demonstrate an essential increase of knowledge by involving an idiographic, qualitative component into the assessment procedure (but still allowing for quantitative classification). Diener and Fujita (1995) observed on a quantitative level that resources correlate more closely with SWB if they are deemed more important by the individual under consideration. Our results also merge well with Kim-Prieto et al.’s (2005) integrative model for the various stages of the evaluation process, ranging from events and circumstances, experienced emotions, and recalled emotions to the final global valuation, whereby personality can play a moderating role on each of the stages, since different persons experience different events, react and recall differently, and use different criteria for the global judgment.

The proposed approach would require intense effort (including human resources and interdisciplinary working teams), of course, and it seems particularly unlikely that national surveys would include qualitative interviewing, but it should certainly be considered for supplemental studies. From a scientific point of view, such an approach is substantially more promising than running an assessment, ranked so highly on the political agenda, without firm qualitative evidence. A major disaster in SWB research would be that people do not do well, but researchers fail to recognize. Our results strongly suggest that relying exclusively on standard self-rating questions will not protect against this danger.

References

Alicke, M. D. (1985). Global self-evaluation as determined by the desirability and controllability of trait adjectives. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 49(6), 1621–1630.

Alkire, S., & Foster, J. (2011). Counting and multidimensional poverty measurement. Journal of Public Economics, 95(7), 476–487.

Angner, E. (2005). Is it possible to measure happiness? The measurement-theoretic argument against subjective measures of wellbeing. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.92.7559&rep=rep1&type=pdf. Accessed April 21, 2015.

Bergman, L. R., & Magnusson, D. (1997). A person-oriented approach in research on developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 9, 291–319.

Biswas-Diener, R., Vittersø, J., & Diener, E. (2005). Most people are pretty happy, but there is cultural variation: The Inughuit, the Amish, and the Maasai. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(3), 205–226.

Cantril, H. (1965). The pattern of human concerns. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press.

Cummins, R. A. (2003). Normative life satisfaction: Measurement issues and a homeostatic model. Social Indicators Research, 64(2), 225–256.

Cummins, R. A., & Nistico, H. (2002). Maintaining life satisfaction: The role of positive cognitive bias. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 37–69.

Diamantopoulos, A., & Winklhofer, H. M. (2001). Index construction with formative indicators: An alternative to scale development. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(2), 269–277.

Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and a proposal for a national index. American Psychologist, 55(1), 34–43.

Diener, E., & Diener, C. (1996). Most people are happy. Psychological Science, 7(3), 181–185.

Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, G. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

Diener, E., & Fujita, F. (1995). Resources, personal strivings, and subjective well-being: A nomothetic and idiographic approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(5), 926–935.

Diener, E., Inglehart, R., & Tay, L. (2013). Theory and validity of life satisfaction scales. Social Indicators Research, 112(3), 497–527.

Easterlin, R. A. (1974). Does economic growth improve the human lot? Some empirical evidence. In P. A. David & M. W. Reder (Eds.), Nations and households in economic growth: Essays in honor of Moses Abramovitz (pp. 89–125). New York: Academic Press.

Easterlin, R. A., McVey, L. A., Switek, M., Sawangfa, O., & Zweig, J. S. (2010). The happiness—income paradox revisited. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 107(52), 22463–22468.

Eurofound. (2005). European quality of life surveys. http://eurofound.europa.eu/surveys/eqls. Accessed April 21, 2015.

European Commission. (2015). About beyond GDP. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/beyond_gdp/background_en.html. Accessed April 21, 2015.

Fleiss, J. L. (1986). The design and analysis of clinical experiments. New York: Wiley.

Fujita, F., & Diener, E. (2005). Life satisfaction set point: Stability and change. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88, 158–164.

Gross, J. J. (2002). Emotion regulation: Affective, cognitive, and social consequences. Psychophysiology, 39(03), 281–291.

Grünwald, K. (2014). Über die Manifestation von Abwehrmechanismen in qualitativen Interviews zum Thema subjektives Wohlbefinden (Master thesis). [On the manifestion of defense mechanisms in qualitative interviews about subjective well-being.] Vienna: University of Vienna.

Haybron, D. M. (2008). Philosophy and the science of subjective well-being. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being: Critical perspectives (pp. 17–43). New York: Guilford Press.

Kahneman, D., & Krueger, A. B. (2006). Developments in the measurement of subjective well-being. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(1), 3–24.

Kim-Prieto, C., Diener, E., Tamir, M., Scollon, C., & Diener, M. (2005). Integrating the diverse definitions of happiness: A time-sequential framework of subjective well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 6(3), 261–300.

King, G., Murray, C. J., Salomon, J. A., & Tandon, A. (2004). Enhancing the validity and cross-cultural comparability of measurement in survey research. American Political Science Review, 98(1), 567–583.

Köke, S., & Perino, G. (2014). How to measure life satisfaction: A constructive critique. In P. Krause, J. Ordemann, L. Reitzig, & S. Wolf (Eds.), The XII. Quality of life conference book of abstracts. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin.

Krueger, A. B., & Schkade, D. A. (2008). The reliability of subjective well-being measures. Journal of Public Economics, 92(8), 1833–1845.

Krueger, A. B., & Stone, A. A. (2014). Progress in measuring subjective well-being. Science, 346, 42–43.

Larsen, R. J., Diener, E. D., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). An evaluation of subjective well-being measures. Social Indicators Research, 17(1), 1–17.

Layard, R. (2010). Measuring subjective well-being. Science, 327, 534–535.

Lucas, R. E., Diener, E., & Suh, E. (1996). Discriminant validity of well-being measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(3), 616–628.

Mc Kennell, A. C. (1978). Cognition and affect in perceptions of well-being. Social Indicators Research, 5(1–4), 389–426.

Michalos, A. C., & Kahlke, P. M. (2010). Stability and sensitivity in perceived quality of life measures: Some panel results. Social Indicators Research, 98, 403–434.

NIH (2015). Any mental illness (AMI) among adults. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/prevalence/any-mental-illness-ami-among-adults.shtml. Accessed April 21, 2015.

OECD. (2013a). How’s life? 2013: Measuring well-being. Paris: OECD.

OECD (2013b). Guidelines on measuring subjective well-being. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/978926419165. Accessed April 21, 2015.

Oswald, A. J., & Wu, S. (2010). Objective confirmation of subjective measures of human well-being: Evidence from the USA. Science, 327, 576–579.

Pavot, W. (2008). The assessment of subjective well-being. Successes and shortfalls. In E. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 124–143). New York: Guilford Press.

Ponocny, I., Weismayer, Ch., Dressler, S., & Stross, B. (2015). The MODUL study of living conditions. https://www.modul.ac.at/uploads/files/user_upload/Technical_Report_-_The_MODUL_study_of_living_conditions.pdf. Accessed April 21, 2015.

Rojas, M. (2005). A conceptual-reference theory of happiness: Heterogeneity and its consequences. Social Indicators Research, 74(2), 261–294.

Rozin, P., & Royzman, E. B. (2001). Negativity bias, negativity dominance, and contagion. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 5(4), 296–320.

Schwarz, N., Knäuper, B., Oyserman, D., & Stich, C. (2008). The psychology of asking questions. In E. de Leeuw, J. Hox, & D. Dillman (Eds.), International handbook of survey methodology (pp. 18–34). New York: Taylor & Francis.

Schwarz, N., & Strack, F. (1999). Reports of subjective well-being: Judgmental processes and their methodological implications. In D. Kahneman, E. Diener, & N. Schwarz (Eds.), Well-being: Foundations of hedonic psychology. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Shmotkin, D. (2005). Happiness in the face of adversity: Reformulating the dynamic and modular bases of subjective well-being. Review of General Psychology, 9(4), 291.

Statistics Austria (2012). Wie geht’s Österreich: 79% der Bevölkerung mit Lebenssituation zufrieden; materielle Lebensbedingungen, Gesundheit und Partnerschaft wichtige Faktoren für Lebenszufriedenheit. [“How’s Austria”: 79% of the population satisfied with their life situation; material living conditions, health and partnership important factors.] http://www.statistik.at/web_de/presse/073264. Accessed April 21, 2015.

Staudinger, U. M. (2000). Viele Gründe sprechen dagegen, und trotzdem geht es vielen Menschen gut: Das Paradox des subjektiven Wohlbefindens. [In spite of many causes, many people are well off: The paradox of subjective well-being]. Psychologische Rundschau, 51(4), 185–197.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2008). Economic growth and subjective well-being: Reassessing the Easterlin paradox. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Stiglitz, J. E., Sen, A., & Fitoussi, J. P. (2010). Report by the commission on the measurement of economic performance and social progress. Paris: Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress.

Tomyn, A. J., & Cummins, R. A. (2011). Subjective wellbeing and homeostatically protected mood: Theory validation with adolescents. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12(5), 897–914.

Veenhoven, R. (1991). Is happiness relative? Social Indicators Research, 24, 1–34.

Veenhoven, R. (1995). World database of happiness. Social Indicators Research, 34(3), 299–313.

Veenhoven, R. (2009). International scale interval study: Improving the comparability of responses to survey questions about happiness. In V. Moller & D. Huschka (Eds.), Quality of life and the millennium challenge: Advances in quality-of-life studies, theory and research. Social Indicators Research Series (Vol. 35, pp. 45–58). Netherlands: Springer.

Veenhoven, R., & Vergunst, F. (2014). The Easterlin illusion: Economic growth does go with greater happiness. International Journal of Happiness and Development, 1(4), 311–343.

WHO. (2015). Mental health. Data and statistics. http://www.euro.who.int/en/health-topics/noncommunicable-diseases/mental-health/data-and-statistics. Accessed April 21, 2015.

Zapf, W. (1984). Individuelle Wohlfahrt: Lebensbedingungen und Wahrgenommene Lebensqualität. In W. Glatzer & W. Zapf (Eds.), Lebensqualität in der Bundesrepublik (pp. 13–26). New York: Frankfurt a. M.

Acknowledgments

This research results from a project funded by the Anniversary Fund of the Austrian National Bank (OeNB), Proj. No. 14399.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Ponocny, I., Weismayer, C., Stross, B. et al. Are Most People Happy? Exploring the Meaning of Subjective Well-Being Ratings. J Happiness Stud 17, 2635–2653 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9710-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-015-9710-0