Abstract

This paper contributes to the discussion on the effects of single motherhood on happiness. We use a mixed-method approach. First, based on in-depth interviews with mothers who gave birth while single, we explore mechanisms through which children may influence mothers’ happiness. In a second step, we analyze panel survey data to quantify this influence. Our results leave no doubt that, while raising a child outside of marriage poses many challenges, parenthood has some positive influence on a lone mother’s life. Our qualitative evidence shows that children are a central point in an unmarried woman’s life, and that many life decisions are taken with consideration of the child’s welfare, including escaping from pathological relationships. Our quantitative evidence shows that, although the general level of happiness among unmarried women is lower than among their married counterparts, raising a child does not have a negative impact on their happiness.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Becoming a parent brings with it both pressures and rewards. Thus, having children may raise adults’ levels of happiness, but it may also elevate their feelings of anxiety and cause them psychological distress. Parenthood may have especially negative consequences for the psychological well-being of single parents. While married parents generally share the financial and emotional effort involved in bringing up a child with their spouse, most lone parents—usually women—do not receive support from the child’s father or his family. They are also particularly vulnerable to the risk of falling into poverty, and must cope with tensions resulting from the double burden of breadwinning and care provision (Christopher et al. 2002; Mejer and Siermann 2000; Casper et al. 1994). Because they have more duties to juggle than most married mothers, lone mothers are more apt to limit their participation in social activities (Cairney et al. 2003). The subjective well-being of lone mothers may be particularly affected in societies in which the level of acceptance for raising children outside of marriage is low, and in which welfare state support for parents—and especially for lone parents—is limited.

In light of the above, this paper seeks to investigate the role of motherhood in single mothers’ lives and evaluate its impact on single mothers’ happiness. Previous research on this topic has presented a multifaceted but fragmented image of lone motherhood. Quantitative studies have compared the magnitude of selected symptoms of (un)happiness among married and lone mothers, pinpointing the disadvantage of the latter group. Meanwhile, the qualitative research has emphasized that, in some circumstances, lone motherhood may bring important benefits to women’s lives.

This paper contributes to the ongoing discussion on the role of parenthood for single women’s happiness by offering more comprehensive and critical insights into this problem. More precisely, we use a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods in a single research context, which allows us to look at the situation of single mothers from two different perspectives and to better recognize and interpret the studied phenomenon. We apply the qualitative approach to explore the positive and negative aspects of lone motherhood and detect possible mechanisms through which motherhood may contribute to or detract from levels of happiness among single women. The quantitative study seeks to determine whether the positive or the negative aspects of lone motherhood predominate in a representative sample of women. Importantly, longitudinal survey data and panel econometric techniques of data analysis are employed to assess the overall impact of having a child on the happiness levels of single mothers, net of other life events and conditions.

Our study is conducted in the context of Poland. We consider this country to be an interesting case study for this type of research for two reasons. First, because the Poles tend to have strong Catholic values, the degree of acceptance of nonmarital childbearing is still relatively low. Second, unlike in some Western European countries, lone mothers in Poland receive very limited support from the welfare state (Kotowska et al. 2008; Piętka 2009). Given these unfavorable conditions, the data for Poland provide a favorable context for a “conservative test” of the effects of having a child on the happiness of an unpartnered woman.

2 Literature Review

The situation of single mothers has been intensively investigated, especially in the United States. This field of research is quite varied. Researchers have employed quantitative and qualitative methods, and have used a number of different indicators of subjective well-being. They have explored the emotional as well as the cognitive dimensions of the well-being of single mothers, and have used many indirect indicators of subjective well-being, such as self-esteem or stress levels. Regardless of which aspect of subjective well-being was being analyzed, however, the quantitative studies have consistently depicted lone mothers as a disadvantaged group. Compared to married mothers, lone mothers have been shown to be more likely to experience psychological distress or depression (Avison and Davies 2005; Cairney et al. 2003; Cunningham and Knoester 2007; Demo and Acock 1996; Evenson and Simon 2005; McLanahan and Adams 1987; McLanahan 1983; Nomaguchi and Milkie 2003), to report lower levels of self-efficacy (McLanahan 1983; Nomaguchi and Milkie 2003) and self-esteem (McLanahan 1983; Demo and Acock 1996), and to be less hopeful (McLanahan 1983) and less happy (Demo and Acock 1996). The elevated levels of psychological distress among single mothers were found to be largely caused by financial hardship (Hope et al. 1999), as well as by greater exposure relative to married mothers to other stressful life events, such as caregiver pressures or work-family tensions (Avison et al. 2007; Cairney et al. 2003; Dziak et al. 2010).

A more nuanced and less negative picture of lone motherhood has been painted in qualitative studies. They have shown that there are numerous positive as well as negative aspects to raising a child as a single parent. For instance, single mothers who have been interviewed in qualitative studies have expressed very positive attitudes about motherhood, and have said that “motherhood made them feel stronger, more competent, more connected to family and society and more responsible” (Duncan 2007). These studies, though usually conducted among very young women from poor neighborhoods, have shown that single mothers “seldom view an out-of-wedlock birth as a mark of personal failure” (Edin and Kefalas 2005), but rather as a turning point in their lives. Despite the fact that the experience of daily hardship in raising a child on their own is clearly visible in their narratives (struggling with financial difficulties, time constraints, or social stigma), the single mothers interviewed described how motherhood brought a sense of purpose to their lives (SmithBattle 2000), increased their self-esteem and social status (Bell et al. 2004; Edin and Kefalas 2005), and gave them an impetus to change their lives for better; e.g., to take up education or employment (Duncan 2007), abandon abusive behaviors (SmithBattle 2000), escape from an unhappy parental home, gain independence and a new identity, and “create a loving family of one’s own” (Coleman and Cater 2006).

Although the qualitative studies do not tell us what the overall impact of childbirth is on the subjective well-being of single mothers, they suggest that a more careful consideration of quantitative findings is called for, especially since previous quantitative studies are not without limitations. Specifically, most quantitative studies have so far focused on the narrowly defined and usually indirect indicators of psychological well-being, such as the risk of depression, anxiety, or psychosomatic illness. Moreover, they usually use cross-sectional data and compare different aspects of the subjective well-being of single and married mothers. Such a cross-sectional approach may lead to very misleading results for at least two reasons. First, previous studies did not separate out the effect of being single from the effect of having a child, despite evidence that having a partner is an important determinant of psychological well-being (Dolan et al. 2008). Second, the available quantitative studies failed to control for a selection of particularly vulnerable women into the group of single mothers, even though it has been demonstrated that women with adverse childhood experiences—and who are, therefore, susceptible to depression—are overrepresented among lone mothers (Davies et al. 1997; Lipman et al. 2010). Both failures might have led to an overestimation of the negative impact of having a child on single mothers’ well-being. Finally, the available cross-sectional studies compared the situations of married and single mothers, but they did not tell us whether the lives of single mothers would have been better if they had not given birth to a child. In this paper, we attempt to overcome these limitations and investigate the effect of single motherhood on women’s general level of happiness in the conservative context of Poland.

3 The Institutional and Cultural Context in Poland

Childbearing in the Polish context is clearly connected to marriage. Cohabitation is infrequent, and it is a prelude to marriage rather than a family arrangement which would be perceived as appropriate for parenthood (Mynarska and Matysiak 2010). Moreover, even those women who conceive a child while unmarried tend to arrange a wedding while they are pregnant, although this tendency has declined in recent years (Baranowska 2011). As a result, women who give birth out of wedlock and remain unmarried are a minority in Poland, and single mothers constitute only a segment of this group.

The well-being of any marginal group depends to a large extent on whether society accepts or stigmatizes its members. The opinions of Poles are greatly influenced by the Roman Catholic Church, which affects social norms and attitudes with regard to family formation. According to data from the International Social Survey Program (2008), over 90 % of Poles were raised in the Catholic religion (compared with an average of 49 % in other EU member states). Empirical studies with a cross-country comparative perspective have confirmed that the level of social disapproval of “alternative family types,” such as single parenthood, is relatively high in Poland (Chapple 2009; Vanassche et al. 2012).

On top of these negative cultural attitudes toward single parenthood, the institutional arrangements in Poland are not supportive of lone mothers. The Polish state provides a rather low level of support for families in general, including lone parents. Financial transfers are means-tested (Kotowska et al. 2008) and are quite low relative to other countries. For instance, the average child maintenance payment per sole-parent family in Poland amounts to 166.80 USD (measured in purchasing power parity), compared to 436.30 USD in the U.S. (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD 2008a). The limited welfare state support for lone parents has serious consequences for the financial standing of these families. According to OECD statistics, the average disposable income of a household in Poland led by a single parent is 51 % of the income of a childless couple (Fig. 1). Thus, welfare support in Poland does little to eliminate the income gap between single parents and childless couples.

Poland also has the worst system of public childcare provision in the EU (OECD 2008b). Even though single mothers are granted some additional points when applying for a place in public childcare, only around 20 % of children aged 0–6 raised by single mothers attend public childcare in Poland (authors’ calculations based on data from European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions).

In sum, in Catholic Poland, bearing a child out of wedlock is not socially accepted, and lone parenthood is not institutionally supported. Thus, the specific cultural and institutional context of Poland should qualify this case study as a “conservative test” for investigating the impact of motherhood on the happiness of unpartnered women.

4 Methodology

4.1 Research Design

In order to investigate the role of childbearing in the lives of single mothers, we combined qualitative and quantitative methods. The mixed-method approach is increasingly being advocated in the social sciences (e.g. Bryman 1988; Giele and Elder 1998; Sale et al. 2002). Using different approaches, as well as different methods and data sets within each paradigm (methodological triangulation), allows us to formulate interpretations of social phenomena that are deeper and more valid. In our study, we employ qualitative methods—i.e., content analysis of semi-structured interviews—to identify the positive and the negative aspects of lone motherhood, and to reconstruct women’s perceptions of how giving birth while single has affected their lives. In the next step, we apply quantitative methods—i.e., panel econometric techniques—to assess the overall impact of having a child on single mothers’ happiness.

By integrating these two methodological approaches into a single research context we are able to offer a more comprehensive picture of single motherhood, which was not possible in previous studies that used a qualitative or a quantitative approach only. First, we are consistent with respect to the population under study. While previous qualitative research usually referred to never-married women, the quantitative research investigated all single mothers, including the divorced and widowed. We focus on lone mothers who were never married in both parts of our study, but in the quantitative part we also display results for previously partnered mothers. Second, we do not restrict our sample to teenage women from poor neighborhoods, as has often been the case in qualitative studies on this topic. Instead, we study women from various social backgrounds, which allows us to gain a wider perspective on the role of childbearing in lone mothers’ lives. Third, we do not restrict our analysis to narrowly defined or indirect indicators of well-being, but instead attempt to provide an overall subjective evaluation of the mothers’ happiness.

The advantages of our study lie not only in its mixed-methods design, but also in the characteristics of our quantitative component. In contrast to the available quantitative studies, which compared the subjective well-being of married and single mothers, we use longitudinal data to investigate how the arrival of a child changes the happiness of women with different marital and partnership statuses. Additionally, we apply econometric techniques that eliminate bias from the selection of women who are “innately unhappy” (due to childhood experiences or personality traits) into the group of lone mothers. Our quantitative analyses address the question of whether single women would be indeed happier if they had not given birth to a child, instead of the question of which group of mothers, single or married, are happier.

4.2 The Qualitative Study

4.2.1 Participants

Our qualitative data come from semi-structured face-to-face interviews which were conducted in 2011 within the research project “Family change and subjective well-being” (FAMWELL). The aim of the project was to explore new and currently rare family developments in Poland. In particular, the project seeks to investigate what life-course developments and circumstances lead individuals to arrive at certain family arrangements (e.g., lone motherhood), and to study how these developments affect individuals’ subjective well-being. Within this project, we conducted 35 interviews with women who experienced an extramarital birth. The interviews were conducted in cooperation with TNS OBOP research agency. The agency recruited the respondents using a snowball method: in several locations in Poland (three voivodeships; three towns or cities in each of them) the networks of the agency pollsters were used to snowball for women who were aged 25–39 and who had ever experienced an extramarital birth. Out of the 35 women recruited, 16 were cohabiting with their child’s father at the time of the interview, and they were excluded from the analyses. Another three women were raising their child with the child’s father for a prolonged period of time, and they were also dropped from the sample. This left us with a final sample of 16 women. None of these women was married before giving birth. In 12 cases, their relationship with the child’s father ended during the pregnancy. The remaining four women had separated from the child’s father at some point after the birth of the child (1–4 years). We decided to include them in the sample because all of them reported very serious problems in their relationships during the pregnancy; thus, even though the final termination of the relationship took place later, they said they felt like they were “single mothers” from the very beginning. Eight women in the sample were in a relationship with a new partner at the time of the interview, while the other eight were single. They all, however, experienced periods in which they were raising their child without any support from a partner during the early stages of the child’s life.

Our interviewees were 26–38 years old, and their main characteristics are presented in the table below. Importantly, we did not limit our sample to teenage mothers, nor did we select women from any particular city, neighborhood, or social group. The study was conducted in several locations in Poland; in large cities as well as in small towns. We looked for women from different social backgrounds and with different educational levels (Table 1).

The heterogeneity of the sample is apparent if we also consider the occupations of the respondents. We interviewed shop assistants, a cleaner, a hairdresser, an employee of a wholesale poultry vendor, a sales agent, an insurance agent, a social worker, an assistant in a law firm, and office workers.

4.2.2 Measurement Instruments

The interviews were semi-structured and problem-centered. The interview guideline was designed to reconstruct a history of how the respondent became a lone mother, and to explore how this event influenced her life and general level of happiness. Three thematic areas were covered in each interview. First, the respondents were asked to describe their life situations, with a special focus on their family and living arrangements. Next, questions designed to reconstruct a history of how the woman became a lone mother were asked. This second section always started with a question about how the respondent had imagined her family life as an adult when she was young. The respondents were asked to describe their desires and intentions related to family formation, and then to discuss the factors that, in their opinion, encouraged or discouraged the realization of these intentions. The respondents were prompted to consider various life events that might have been relevant (related to education, work, and relationships), and to discuss the roles played by other people (family, friends). In the third and final section of the interview, each woman was encouraged to imagine what her life would have been like if she had ended up in a more “traditional” family arrangement. In this section, each respondent was asked whether, on the whole, she would have been more or less happy if she had raised her child with the child’s father. This question was followed by questions on the respondent’s overall sense of life satisfaction and on the main sources of her feelings of happiness or distress.

All of the interviews were conducted following the above scenario, but the interviewers were allowed to adjust the wording of the questions to fit the interview flow and the specific characteristics of each respondent. The interviews were conducted by four experienced qualitative interviewers, who were women aged 22–32 (similar to the ages of the respondents, which allowed them to build a better rapport). All of the interviewers were instructed, coached, and supervised by the study coordinator.

4.2.3 Procedure and Data Analysis

A content analysis of the interviews was conducted to identify all of the positive and negative aspects of lone motherhood, as perceived by the respondents. The coding was performed by the coordinator of the qualitative study (a 35-year-old woman with a degree in psychology and several years of experience in collecting and analyzing qualitative data). We analyzed the data using a bottom-up coding procedure. NVivo 9 software was used to facilitate the process. First, we identified all of the passages in which any reference to childbearing and lone motherhood was made. This material was coded using the open coding procedure (Strauss and Corbin 1998). Next, the open codes were merged into categories. Nine categories emerged, which are presented in a table in the Appendix. In the next step, a matrix of all of the interviews and the categories was created. The matrix contained the key statements made by the respondents or short summaries of what they said during the interview in each of the categories. This matrix allowed us to conduct an efficient analysis of the content of each category, and made it easy to retrieve key quotations. The negative or positive aspects of lone motherhood, as revealed by the respondents, were identified for each category.

4.3 The Quantitative Study

In a second step, we turned to quantitative methods to estimate the general impact of giving birth to a child on the happiness of the unpartnered women. To this end, we used survey data from Social Diagnosis. Social Diagnosis is a panel multi-purpose survey designed to provide a regular assessment of the living conditions and the quality of life of the Polish population. To the best of our knowledge, it is the largest and most comprehensive panel survey carried out in Central and Eastern Europe that includes questions on happiness (Filer and Hanousek 2002). The individual-level data and survey documentation are available in the public domain (on the website www.diagnoza.com).

Social Diagnosis was conducted for the first time in 2000 on a random sample of 3,005 households. All of the household members aged 16 or above were supposed to be interviewed. They were interviewed again in 2003, and every 2 years thereafter. At each wave information on the respondents’ living conditions, family situations, education, labor market participation, health, and various aspects of subjective well-being (including general happiness) was collected.

4.3.1 Participants

Altogether, in all six waves, 65,282 face-to-face interviews were conducted (Czapiński and Panek 2011). For our analysis, we used data from the second and subsequent waves, as the question measuring happiness in the first wave was not comparable with the questions in the following waves. We selected women who entered the survey at ages 18–35; i.e., at childbearing and childrearing ages. This gave us a sample of 15,246 female observations. Around half of them (7,633) were mothers, among whom 538 were never married, 6,594 were married, and 501 were previously married (divorced or widowed). Cohabiting women were dropped from our sample, as we found only 87 such cases.

4.3.2 Measurement Instruments

In our study, we measured the self-rated general level of happiness, derived from a single-item question: “In general, would you say you are very happy, quite happy, somewhat happy, or not at all happy?”; with responses coded on a four-point scale. In the context of this study, this measure has the advantage of brevity. It was adapted from the World Value Survey, and a similar question is also included in other large cross-national or country-specific surveys. Single-item measurement is considered to be less reliable than multi-item scales, but an overall level of happiness is frequently measured with only one question, providing scores of satisfactory validity and reliability (e.g., Holder et al. 2010; Holder and Klassen 2010; Swinyard et al. 2001; Abdel-Khalek 2006).

Our main explanatory variable was created through an interaction of the fact of having a child with a woman’s marital status. Among our control variables, we included a set of observed person-specific characteristics, such as the respondent’s age, educational attainment (including participation in education), self-rated health, self-rated income level, and the age of the youngest child.

4.3.3 Procedure and Data Analysis

We modeled the i-th respondent’s self-rated happiness at any point in time t as a function of our key explanatory variables (the fact of having a child interacted with a woman’s marital status—child_mstat) at time t, a set of the observed individual-level characteristics measured in the survey at time t (obs_characteristics), as well as unobserved individual time-invariant traits ui. Additionally, respondent’s self-rated happiness was subject to random error εit, which may capture random, idiosyncratic influences, such as good weather on the day of the interview or an exceptionally good mood of the respondent. Hence, the model can be written in the following way:

where the parameter β0 represents a constant, β1 reflects the effect of a child-partnership status on happiness and β2 shows the effect of individual-level characteristics (age, education, satisfaction with health, satisfaction with income, labor market situation of the mother and her partner) on happiness.

The most common approach to controlling for individual-specific unobserved characteristics with the panel data is to estimate fixed-effects models. Fixed-effects models are based on the variation of the respondent’s characteristics across time, and hence remove the potential bias resulting from the selection of “intrinsically (un)happy” individuals into the group of lone parents. In this paper, we employed two different fixed-effects estimators which were developed specifically for models with ordered dependent variables: namely, the FCF estimator proposed by Ferrer-i-Carbonell and Frijters (2004), and the “blow-up and cluster” (BUC) estimator recently developed by Baetschmann et al. (2011). The former is probably the best known tool used for estimating the fixed-effects ordered logit models, but it yields inconsistent estimates on panel data with a small number of waves (Baetschmann et al. 2011). Because the latter was shown to be less sensitive to the number of panel waves (Baetschmann et al. 2011), it might be better suited to our data with five waves. In addition to using these fixed-effects models, we also estimated a correlated random-effects ordered probit model, which draws on the approach proposed by Mundlak (1978), and, like the fixed-effects models, allows us to remove the selection bias. It decomposes the unobserved time-constant individual effect ui into a random effect, which is uncorrelated with the explanatory variables and the mean values of the time-varying regressors that are expected to be correlated with the individual random effects (Mundlak 1978). The estimates produced by this method are least sensitive to the number of panel waves, and are more robust to the incidental parameter problem (Greene and Hensher 2010).

5 Results

5.1 Qualitative Evidence

The interviewed women mentioned a number of positive and negative aspects of lone motherhood. The negative aspects were mainly related to the painful separation from the child’s father, which in some cases took place after conception; or to the financial or organizational difficulties associated with managing on their own. However, when it came to motherhood itself, the interviewed women consistently expressed very positive emotions. Furthermore, like other qualitative studies, our findings, presented in the following section, showed that motherhood motivated the interviewed women to take actions which they claimed to have undertaken for the good of the child, but which had positive consequences for the women as well. All of the categories revealed in the data are displayed in the Appendix. Below, we present a more detailed discussion of their content, starting with the negative aspects of lone motherhood.

5.2 Negative Aspects of Lone Motherhood

For the vast majority of the interviewed women, the termination of the relationship with the child’s father took place during the pregnancy (in 12 out of 16 cases). This was the first painful experience related to the pregnancy that the women had to go through. Women who were left by the child’s father—sometimes after they had been together for several years—said they were completely “terrified.” They felt betrayed and abandoned. Even when it was the woman’s decision to leave her partner, this choice was usually made to protect the child from violence, alcohol, or drugs; and was still associated with a wide range of negative emotions.

Clearly, the negative emotions of our respondents were directed toward the former partner and not toward becoming a mother. Nevertheless, these painful experiences decreased the women’s levels of happiness with pregnancy and childbearing, especially since in most cases the pregnancy had not been planned (only two women described their pregnancy as “intended”). The separation from the partner occurred when he was needed the most. The respondents did not mention feeling any joy and excitement related to pregnancy. Instead, they repeatedly emphasized that they “had no choice and had to manage” on their own.

The perception that lone motherhood is far more demanding than raising a child with a partner was identified as one of the main negative aspects of lone motherhood. More than half of the respondents emphasized that raising a child without a partner’s support had been “very tiring” and stressful. They felt overwhelmed by childrearing responsibilities. Anna, who was left by her partner when she was pregnant, described her experience as follows:

I had always been independent and I had never needed anyone (…) when the baby was born I realized that the second person, this partner, was very much needed after all, that I would not manage on my own with everything. (Anna, a child at 28)

The respondents emphasized that they lacked not only practical help, but also emotional support from a partner. Lone motherhood was associated with feelings of loneliness and seclusion. These emotions are not specific to lone motherhood, and can be felt by single childless women as well. But our respondents clearly found raising a child more emotionally strenuous because of the lack of a partner. As one of the respondents explained it:

I missed having a man who would support me, give me his shoulder to lean on; who would say ‘come on, don’t break down’ when my child was—I don’t know—in the hospital with bronchitis or something like that. Somebody to give me his shoulder to cry on. (Beata, a child at 19)

Single motherhood is also demanding financially. In the respondents’ words, “two salaries are better than one,” so they naturally noted that their material situation would have been better with a partner’s income. Some of them admitted that it is extremely difficult to live and raise a child on one salary only. Three women said that they would have not managed to provide for their child without financial support from their parents. Three others admitted that becoming a lone mother at a young age interfered with their plans to continue their education, and hence jeopardized their chances of getting a better paid job. In general, the financial hardships associated with lone motherhood were mentioned in 10 interviews.

The final negative aspect of lone motherhood identified by the respondents is related to the social perception of single mothers. This topic was discussed in 13 interviews. For two women, the social stigmatization of lone motherhood took an extreme form: they were rejected by their family and acquaintances, and, facing condemnation in their social environment, they left their home community and moved to a bigger city to start a new life. In other cases, the degree of social disapproval was not as strong, but the respondents spoke of having problems or “unpleasant situations” at church or at school. They felt uncomfortable when they had to answer questions about the child’s father, even among friends. They felt “ashamed” and “worse.” Six respondents said explicitly that being a single mother makes them less attractive for new partners. They said they believe that men are not interested in “raising another man’s child,” and that a woman with an illegitimate child is seen as “handicapped.” One respondent explained:

I’m an old maid with a child. I am seen as something second-best. Exactly the way I see divorced men, they are second-best, there is something wrong with them. And that’s how people see me. I’m a single and with a child, so there is something wrong with me. (Barbara, a child at 33)

Despite these negative aspects related to lone motherhood, the respondents also mentioned a number of positive consequences of becoming a single mother.

5.3 Lone Motherhood: Not Just a Bad Thing

The first positive consequence of becoming a mother is that the interviewed women decided to take steps which they had been afraid to take before the pregnancy, but which clearly made their lives better. One of these decisions was to separate from the child’s father. Although it was viewed as an emotionally painful experience, as we showed in the previous section, in many cases the separation meant that the woman was exiting a highly unsatisfactory or even pathological relationship. This applies to 11 women, and for five of them, becoming a mother ended a relationship with an abusive partner who used alcohol or drugs, or who was violent. In two cases, the partner abandoned the pregnant woman, while in three others, the respondents decided to leave for the sake of their future child. As one woman explained it:

If I hadn’t got pregnant, I would have probably got stuck in this relationship longer, but then I had to care for a child (…) I would not let my child be given a beer instead of a cocoa for breakfast… or see her father drinking a glass of vodka, no way. (Renata, a child at 21)

Another respondent with a similar history gave almost the same account::

The man I used to be with, he had problems with alcohol and drugs. It was the reason why I left him. I didn’t think only about myself—but about the child, too. I had to start thinking… I had been hesitating before, I had wanted to leave him, but you know… love is blind. And it could be said that M. [a daughter] simply pushed me to do it. (Kamila, a child at 27)

Naturally, not all 11 cases of unsatisfactory relationships included violence or alcohol. In all of them, however, the women were of the opinion that they would have suffered in their relationship with the child’s father. They would have felt “emotionally exhausted,” “unhappy,” or “mistreated.” While they acknowledged the hardships associated with lone motherhood, they unanimously stated that it is better to live without a partner than to have a partner like the one they were with when they became pregnant. One respondent said:

There was a time when it was nice. We could count on each other, as it usually is at the beginning. But the magic disappeared, a fairy tale ended and I said I wanted to be alone, because this way it would be better for me and for my child. (Julia, a child at 24)

Renata observed, somewhat brutally:

Maybe one day my son will feel that he lacks a father. But if he was to have an idiot for a father, then it is better for him not to have a father at all. (Renata, a child at 21)

Bad experiences with the child’s father had two other positive outcomes for our respondents. First, the women seemed to be more careful in their current relationships. Because of their responsibilities as a mother, they felt they could not enter into a new relationship hastily. Instead, they said, they would have to be certain that their future partner would be, above all, a good father for their child. Statements of this kind are found in nine interviews. Second, the women who left their abusive partners expressed feelings of pride and accomplishment. The decision made them feel stronger and more in control of their lives. Karolina, for example, expressed this feeling in the following way:

It is my achievement that I managed to leave this guy. For the previous four years I had been thinking about it, imagining it, but I had never thought I would have enough courage to do it (…) But I found courage and I am very happy and very proud. (Karolina, a child at 21)

Receiving social support from family members and friends can also alleviate some of the negative aspects of lone motherhood. Even though some women suffered from social disapproval or rejection, 10 respondents received generous support, including financial support, help with childcare, the offer of a place to stay, and emotional support. Being able to rely on people other than their partner was perceived as very positive. The best example is the case of Aneta, who reported that would not have survived the previous 5 years without her parents’ help. They supported her when she was left by her partner 1 month before the delivery. As she described it:

My parents rose to the challenge right away. They prepared a room for me—because there had been none, as I had planned to live elsewhere [with the ex-partner]. They started to buy things, to bring them home. They kept me busy, so I didn’t think too much about all that had happened. (Aneta, a child at 21)

The parents had also supported her financially since her child was born, covering all of the child-related expenses. At one point in the interview she said: “My parents should get some prize.”

Above all, however, the interviewed women expressed positive emotions while speaking about motherhood itself. In 11 interviews, the respondents recurrently emphasized that their child brings them joy and the motivation to live, and “gives me energy.” Naturally, such declarations are not specific to single mothers. Similar answers could be found in interviews with cohabiting or married mothers. But it is important to note that the many hardships associated with raising a child alone had not diminished the women’s feelings of satisfaction with their child. Indeed, their child was the main source of happiness and satisfaction in the respondents’ lives.

Moreover, for a woman who experiences lone motherhood, her child might be particularly important. The child is the central person in her life, the key person she loves and the main source of affection. This is apparent in Kamila’s observations:

I’m very happy that I have her [a daughter]. Even though she came to this world in these circumstances, I simply know that it would have been really bad without her! She is so much fun and I’m getting older and if I didn’t have her, I don’t know if I would have anybody to love now. (Kamila, a child at 27)

In the above quote, one more aspect is revealed. For single mothers, a child is likely to be the only source of support in the future. Another respondent explained this assumption as follows:

Even if I don’t enter any new relationship, I still have a child. And when I am old, maybe she won’t turn her back on her mother, maybe she will help. (Dagmara, a child at 31)

All in all, a child is perceived as a natural remedy for all of the problems the respondents have experienced; “the most wonderful” and “the most positive” element of their lives. As one woman puts it, “a child’s love compensates for everything.”

5.4 From Qualitative Insights to Representative Sample

The analysis of the interviews gave us important insights into how childbearing shapes the happiness of women who raise a child alone, but it did not enable us to establish whether the positive or negative aspects of lone motherhood dominate in women’s lives, and which of these aspects has the greatest impact on the happiness of single mothers. To address these issues, we performed quantitative analyses on a representative sample, as described in the method section. Our results are displayed in Table 2. Contrary to previous empirical research, they provide no evidence that single motherhood has a negative impact on women’s happiness. It should, however, be noted that our result depends on the method used. Both of the fixed-effects models which applied either the FCF or the BUC estimator yielded a positive but insignificant impact of having a child on the happiness of single mothers. In the correlated random-effects ordered probit model with the Mundlak correction term, the size of the influence was also found to be positive and similarly large, but it was significant. These differences in the significance of the impact of having a child on the happiness of single mothers across model specifications are consistent with what is known about fixed-effects and random-effects models. As the former are based on the variation in respondents’ characteristics across time, they yield less efficient estimates (i.e., they are characterized by greater variance) than the random-effects models, which use both variation across individuals and across time. In any case, we did not find evidence which would suggest that, among single women, raising a child outside of marriage contributes negatively to their happiness.

Although we are mainly interested in the impact of having a child on single women, we also analyzed the impact of parenthood on currently and previously married women. Interestingly, we found more or less the same pattern as we did among single women. Depending on the specification, having a child has a positive effect or has no impact on the self-rated happiness of these two groups of women. The FCF estimate of the impact of parenthood among married mothers is the only exception here: it is negative, but very small and insignificant.

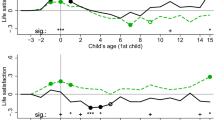

The results from the models presented in Table 2 showed whether the general impact of parenthood on single women is positive or negative, but they do not allow us to infer the magnitude of the effect. Therefore, we computed the marginal effects of having a child for three groups of women: married, single, and previously married. They show a change in the probability of describing oneself as “very happy” after a change in motherhood status from being childless to being a mother. They were estimated based on the correlated random-effects model for a reference person aged 27 who completed upper secondary education, is satisfied with her health, is quite satisfied with her material standard of living, is employed, has a working partner (if she has a partner), and has no children (see Fig. 2). The computed marginal effects show that married women are clearly the most happy, regardless of whether they have children. This finding is consistent with previous research on the impact of marital status on happiness. Single women score much lower on the happiness scale, and the previously married fare the worst, net of all of the characteristics we controlled for in our models. However, the impact of having children on happiness is positive, not only among married women, but also among single women, as well as among the previously married. Moreover, the magnitude of this influence is similar across these three groups, and amounts to about three percentage points.

6 Discussion and Conclusion

This paper contributes to the literature on how having children affects the lives of single, non-cohabiting women. In particular, it evaluates the impact of becoming a mother on their self-rated happiness. This topic is important because of the numerous difficulties single mothers face, ranging from financial and time pressures to social stigma and alienation.

Our findings confirmed the conclusion reached by other quantitative studies that single mothers are disadvantaged, but they did not provide any evidence to support the assumption that it is the arrival of a child that leads to a decline in single mothers’ happiness. First, in our in-depth interviews, women highlighted many negative aspects of lone motherhood, such as organizational and financial pressures, a lack of partner support, and social disapproval of bearing and rearing a child out of wedlock. The negative emotions were, however, mainly expressed in reference to external circumstances, such as ex-partners, the social environment, and economic conditions. Despite these negative aspects, single motherhood was found to evoke many positive feelings, especially related to motherhood itself. Despite all of the difficulties and problems—or maybe because of them—the child is moved to the absolute center of the woman’s universe. Her child is the main focus of her love, the brightest aspect of her life, and her greatest source of joy and happiness. In our qualitative interviews, lone motherhood was described as having other positive consequences for women’s lives. It gave women the power to make decisions they had not been able to make before pregnancy. Specifically, being responsible for the child’s well-being helped the interviewed women escape unhappy and pathological relationships, and made them more cautious and demanding when getting involved with a new partner. This finding complements previous qualitative studies on teenage single mothers that have found that becoming a mother might move a woman’s life onto a better track: it may, for example, motivate her to complete her education, become more independent, or escape a pathological environment (Coleman and Cater 2006; Duncan 2007; SmithBattle 2008, 2000).

Our quantitative findings showed that, even if the positive aspects of motherhood did not outweigh the negative consequences, the positive aspects at least counterbalanced the negative ones, after accounting for differences in women’s educational attainment; labor market status; self-rated health; material standard of living; and time-invariant, woman-specific unobserved characteristics. Depending on the specification of our models, we found that the arrival of a child either had no impact or even increased the happiness of single mothers. The findings for married women were similar. All in all, we found no evidence to support the assumption that the lives of women who became single mothers would have turned out better if they had not given birth and had not decided to raise the child out of wedlock. These findings contradict the conclusions of the majority of quantitative research on the topic, which failed to control for the selection of “innately unhappy” women into the group of lone mothers.

We believe that our findings have important implications for the academic and political discourse on the socioeconomic consequences of single motherhood. Single motherhood, particularly among young people, has often been regarded as one of the most severe social problems, a symptom of the decline of marriage and of the weakening role of “family values,” and thus as a marker of a lack of responsibility and a route to social exclusion. This perception has been strengthened by the erroneous findings of quantitative studies, which usually demonstrated a substantial gap in the well-being of single and married mothers, without looking at how becoming a mother itself shapes women’s lives. Our findings illustrate that children are a focal point in an unmarried woman’s life, and that many important life decisions are made more responsibly for the sake of the child. Motherhood empowers single mothers, increases their sense of responsibility, and allows them to escape pathological environments. Hence, in line with Graham and McDermott (2006) and Duncan (2007), lone motherhood emerges in our study as a route to social inclusion, rather than to exclusion. It is, rather, the wider social environment that erects barriers for single women with children, such as social disapproval, a lack of support, and financial pressure. This finding is especially relevant for Poland and other countries with limited institutional support for lone parents, indicating an urgent need for improving the existing policies but also for changing the public discourse on single mothers.

Despite its advantages, our study also has a number of shortcomings that could be resolved in future research. First, our measure of happiness relies on a single-item indicator. Even though similar indicators have been used in many studies on happiness (cf., Abdel-Khalek 2006), using multi-item measures could give us more reliable information. Second, our dependent variable was happiness, which constitutes only one dimension of subjective well-being. Future research could adopt a more comprehensive view and also look at psychological distress, self-esteem, self-efficacy, hopefulness, or satisfaction with various domains of life, such as living standards or social life. Third, while fixed-effects models control for the time-constant unobserved factors (such as “innate” (un)happiness) that may bias the estimated impact of single motherhood on happiness, we still did not control for the time-varying unobserved influences. Hence, our research design is not fully comparable to an experiment. Obviously, there may have been some events that took place in the adult lives of single women which caused them to become pregnant and affected their happiness. Future research could benefit from exploiting “natural experiments” in order to provide results that are robust with respect to both the time-constant and time-varying unobserved factors that jointly determine the probability of single motherhood and happiness. Finally, we are also convinced that there is considerable potential in cross-country comparative research that evaluates the role of the institutional and cultural factors in shaping the relationship between single motherhood and women’s happiness. As we have emphasized, our analyses focused on a country in which both the cultural and the institutional conditions for single mothers are unfavorable. It is therefore possible that, in countries with a higher degree of social acceptance for alternative family arrangements and better family policies for lone parents, the positive impact of childbearing on happiness may turn out to be much stronger than the one revealed in our findings.

References

Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2006). Measuring happiness with a single-item scale. Social Behavior and Personality an International Journal, 34(2), 139–150.

Avison, W. R., Ali, J., & Walters, D. (2007). Family structure, stress, and psychological distress: A demonstration of the impact of differential exposure. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 48(3), 301–317.

Avison, W. R., & Davies, L. (2005). Family structure, gender, and health in the context of the life course. The Journals of Gerontology Series B Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 60(2), 113–116.

Baetschmann, G., Staub, K. E., & Winkelmann, R. (2011). Consistent estimation of the fixed effects ordered logit model. IZA discussion paper 5443.

Baranowska, A. (2011). Premarital conceptions and their resolution. The decomposition of trends in rural and urban areas in Poland 1985–2009. Working Papers, Institute of Statistics and Demography, Warsaw School of Economics, No 10/2011.

Bell, J., Clisby, S., Craig, G., Measor, L., Petrie, S., & Stanley, N. (2004). Living on the edge: Sexual behaviour and young parenthood in rural and seaside areas. Hull, UK: University of Hull.

Bryman, A. (1988). Quantity and quality in social research (contemporary social research series) (Vol. 18). London, Boston: Unwin Hyman.

Cairney, J., Boyle, M., Offord, D. R., & Racine, Y. (2003). Stress, social support and depression in single and married mothers. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 38(8), 442–449.

Casper, L. M., McLanahan, S. S., & Garfinkel, I. (1994). The gender-poverty gap: What we can learn from other countries. American Sociological Review, 59(4), 594–605.

Chapple, S. (2009). Child well-being and sole-parent family structure in the OECD: An analysis. OECD social employment and migration working papers No 82. Pairs, France: OECD Publishing.

Christopher, K., England, P., Smeeding, T. M., & Phillips, K. R. (2002). The gender gap in poverty in modern nations: Single motherhood, the market, and the state. Sociological Perspectives, 45(3), 219–242.

Coleman, L., & Cater, S. (2006). ‘Planned’ teenage pregnancy: Perspectives of young women from disadvantaged backgrounds in England. Journal of Youth Studies, 9(5), 593–614.

Cunningham, A.-M., & Knoester, C. (2007). Marital status, gender, and parents’ psychological well-being. Sociological Inquiry, 77(2), 264–287.

Czapiński, J., & Panek, T. (2011). Diagnoza Społeczna 2011. Warunki i jakość życia Polaków. Rada Monitoringu Społecznego: Warsaw.

Davies, L., Avison, W. R., & McAlpine, D. D. (1997). Significant life experiences and depression among single and married mothers. Journal of Marriage and Family, 59(2), 294–308.

Demo, D. H., & Acock, A. C. (1996). Singlehood, marriage, and remarriage. Journal of Family Issues, 17(3), 388–407.

Dolan, P., Peasgood, T., & White, M. (2008). Do we really know what makes us happy? A review of the economic literature on the factors associated with subjective well-being. Journal of Economic Psychology, 29(1), 94–122.

Duncan, S. (2007). What’s the problem with teenage parents? And what’s the problem with policy? Critical Social Policy, 27(3), 307–334.

Dziak, E., Janzen, B. L., & Muhajarine, N. (2010). Inequalities in the psychological well-being of employed, single and partnered mothers: the role of psychosocial work quality and work-family conflict. International Journal for Equity in Health, 9(6).

Edin, K., & Kefalas, M. (2005). Promises I can keep: Why poor women put motherhood before marriage. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Evenson, R. J., & Simon, R. W. (2005). Clarifying the relationship between parenthood and depression. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 46(4), 341–358.

Ferrer-i-Carbonell, A., & Frijters, P. (2004). How important is methodology for the estimates of the determinants of happiness? The Economic Journal, 114(497), 641–659.

Filer, R., & Hanousek, J. (2002). Data watch: Research data from transition economies. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16(1), 225–240.

Giele, J. Z., & Elder, G. H. (1998). Methods of life course research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications.

Graham, H., & McDermott, E. (2006). Qualitative research and the evidence base of policy: Insights from studies of teenage mothers in the UK. Journal of Social Policy, 35(01), 21–37.

Greene, W. H., & Hensher, D. A. (2010). Modeling ordered choices. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

Holder, M., Coleman, B., & Wallace, J. (2010). Spirituality, religiousness, and happiness in children aged 8–12 years. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(2), 131–150.

Holder, M., & Klassen, A. (2010). Temperament and happiness in children. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11(4), 419–439.

Hope, S., Power, C., & Rodgers, B. (1999). Does financial hardship account for elevated psychological distress in lone mothers? Social Science and Medicine, 49(12), 1637–1649.

Kotowska, I. E., Józwiak, J., Matysiak, A., & Baranowska, A. (2008). Poland: Fertility decline as a response to profound societal and labour market changes? Demographic Research, 19(22), 795–854.

Lipman, E. L., Kenny, M., Jack, S., Cameron, R., Secord, M., & Byrne, C. (2010). Understanding how education/support groups help lone mothers. BMC Public Health, 10, 4.

McLanahan, S. (1983). Family structure and stress: A longitudinal comparison of two-parent and female-headed families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 45(2), 347–357.

McLanahan, S., & Adams, J. (1987). Parenthood and psychological well-being. Annual Review of Sociology, 13, 237–257.

Mejer, L., & Siermann, C. (2000). Income poverty in the European union: Children, gender and poverty gaps. In Statistics in focus: Population and social conditions (Vol. 3–12). Luxembourg: Eurostat.

Mundlak, Y. (1978). On the pooling of time series and cross section data. Econometrica, 46(1), 69–85.

Mynarska, M., & Matysiak, A. (2010). Diffusion of cohabitation in Poland. Studia Demograficzne, 157–158(1–2), 11–25.

Nomaguchi, K. M., & Milkie, M. A. (2003). Costs and rewards of children: The effects of becoming a parent on adults’ lives. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65(2), 356–374.

OECD. (2008a). Growing unequal—income distribution and poverty in OECD countries. Paris: OECD.

OECD. (2008b). PF11: Enrolment in day-care and pre-school. OECD family database. Public policies for families and children. Paris: OECD.

Piętka, K. (2009). Polityka dochodowa a ubóstwo i wykluczenie społeczne. In B. Balcerzak-Paradowska & S. Golinowska (Eds.), Polityka dochodowa, rodzinna i pomocy społecznej w zwalczaniu ubóstwa i wykluczenia społecznego Tendencje i ocena skuteczności.. Warsaw: Instytut Pracy i Spraw Socjalnych.

Sale, J. E. M., Lohfeld, L. H., & Brazil, K. (2002). Revisiting the quantitative-qualitative debate: Implications for mixed-methods research. Quality & Quantity, 36(1), 43–53.

SmithBattle, L. (2000). The vulnerabilities of teenage mothers: Challenging prevailing assumptions ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 23(1), 29–40.

SmithBattle, L. (2008). Gaining ground from a family and cultural legacy: A teen mother’s story of repairing the world. Family Process, 47(4), 521–535.

Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

Swinyard, W., Kau, A.-K., & Phua, H.-Y. (2001). Happiness, materialism, and religious experience in the US and Singapore. Journal of Happiness Studies, 2(1), 13–32.

Vanassche, S., Swicegood, G., & Matthijs, K. (2012). Marriage and children as a key to happiness? Cross-national differences in the effects of marital status and children on well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies. doi:10.1007/s10902-012-9340-8.

Acknowledgments

The paper was prepared within the research project “Family Change and Subjective Well-Being” (FAMWELL), which was financed by the National Centre for Research and Development under the Program Lider. The authors would like to thank the participants of the conference organized by the Society for Longitudinal and Life Course Studies in Bielefeld in September 2011, the audience of the European Population Conference organized in Stockholm in June 2012, and the participants of the conference organized by the International Society for Quality-of-Life Studies in Venice in November 2012 for their valuable comments. We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers assigned by Editor of the Journal of Happiness for their suggestions of improving this paper. Anna Baranowska-Rataj would like to express her gratitude for the support and hospitality that she received during her research stay at Department of Sociology, Umeå University, where the final version of this paper has been revised.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Baranowska-Rataj, A., Matysiak, A. & Mynarska, M. Does Lone Motherhood Decrease Women’s Happiness? Evidence from Qualitative and Quantitative Research. J Happiness Stud 15, 1457–1477 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9486-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9486-z