Abstract

Advice for a happier life is found in so-called ‘self-help books’, which are widely sold in modern countries these days. These books popularize insights from psychological science and draw in particular on the newly developing ‘positive psychology’. An analysis of 57 best-selling psychology books in the Netherlands makes clear that the primary aim is not to alleviate the symptoms of psychological disorders, but to enhance personal strengths and functioning. Common themes are: personal growth, personal relations, coping with stress and identity. There is a lot of skepticism about these self-help books. Some claim that they provide false hope or even do harm. Yet there are also reasons to expect positive effects from reading such books. One reason is that the messages fit fairly well with observed conditions for happiness and another reason is that such books may encourage active coping. There is also evidence for the effectiveness of bibliotherapy in the treatment of psychological disorders. The positive and negative consequences of self-help are a neglected subject in academic psychology. This is regrettable, because self-help books may be the most important—although not the most reliable—channel through which psychological insights find their way to the general audience.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Guidance for how to live your life has long been sought in religion and philosophy, but nowadays people also seek advice from psychology. Part of this advice is provided in personal consults with professional psychologists, such as test-psychologists, psychotherapists and mental coaches. This kind of help is typically focused on specific psychological problems or choices in life. Yet most psychological advice for improving the quality of one’s life is not obtained in consulting rooms, but picked up from popularizations in the mass media. Psychologists appear frequently on television. Magazines and newspapers often interview psychologists and it is easy to find them on the Internet (Peverelli, 1999; Rabasca, 2000), with more than 12,000 Web sites devoted to mental health (Paul, 2001). There are special interest magazines about psychology for a general audience. Examples are Psychology Today (US), Psychologies Magazine (UK), Psychologies (France), Psychologie Heute (Germany), and Psychologie Magazine and Happinez (Netherlands).

Self-help books

There is also a real abundance of so-called ‘self-help books’ available in bookstores. For every conceivable mental problem and for every life choice there is guidance in print, from what Meyer (1980) has called the positive thinkers. There are books that explain how one can obtain emotional literacy (e.g., Goleman, 1995; Steiner & Perry, 1997), how to become engaged in activities as a way in which to attain happiness (Csikszentmihalyi, 1997), if you should stay with or leave your partner (Kramer, 1997), how to fight depression (Lewinsohn, Munoz, Youngren & Zeiss, 1986), how to stay sane in a crazy world (Lazarus & Lazarus, 1997), how to communicate with your partner (Tannen, 1986, 1990) and what you can and cannot change about yourself (Seligman, 1994). You can even obtain advice whether it is a good idea to kill yourself: Diekstra and McEnery (2001) claim that their book can help a reader to make a more rational decision about life and death.

Starker (1989) counted approximately 3,700 American book titles beginning with the words ‘how to’, and this figure is only a gross underestimation of the number of self-help volumes available, because the authors are not restricted to this title. The self-help industry is a goldmine. Americans spent $563 million on self-help books in 2000 (Paul, 2001). For other countries we were unable to find data, but the genre is prominent in almost every bookstore with a section devoted to psychology in Western Europe and the United States. American self-help authors are also popular in China and the former Eastern block in Europe (personal communication with Sergiu Báltátescu from Rumania and Huaibin Jing from China).

Starker (1989) mentions four pragmatic factors that explain the success of the self-help books:

-

Cost . The costs of self-help books are low compared to a consultation with a psychologist.

-

Accessibility. The books are easy available and can be read over a lunch or during a sleepless night.

-

Privacy. A written solution for problems offers the opportunity to work on problems without ‘going public’ or having to speak to a doctor or psychologist.

-

Excitement. Self-help books quite often become best sellers and buying and reading such a book gives you the opportunity to became part of an in-group. ‘There is no shame in finding your G-spot along with everyone else’.

Plan of this article

This article describes what self-help books are about and explores the effectiveness of this kind of happiness advice.

The first section defines the genre more precisely. For that purpose we will explore what kind of psychology books are sold most often in bookshops and will distinguish the self-help books from other genres. Self-help books are the focus of the rest of the paper.

The next step is a tentative exploration of the readership of these books. Good data is lacking, but the most common themes in self-help books and research of the readers of the Dutch monthly Psychologie Magazine give some indications.

The last part of the paper is about the more difficult question of the effectiveness of this advice. An overview of the drawbacks of the genre is given and then we review the available empirical indications of effectiveness.

The nature of self-help books

A dictionary description of self-help is “the acts of helping or bettering oneself without the aid of others”. In the context of psychology books self-help is a form of coping with one’s personal or emotional problems without professional help. Therefore, all books that can serve this practical aim are considered self-help books.

Themes in self-help books

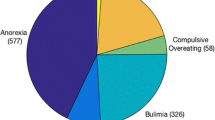

In order to get a view of what self-help books are about, we first listed the best-selling psychology books in the Netherlands and next selected the self-help books on that list. We started with ‘best selling’ books since the aim is on books for a large audience and focused on ‘psychological’ books because the focus is on quality of life. This focus on psychology books implies that other kinds of advisory books are left out, in particular the variety of spiritual books and the volumes about physical health, diets and appearance.

The list of best-selling psychology books was made with the help of a Dutch publisher.Footnote 1 She had contacted a range of bookstores and asked which psychology books sold best locally in the time period of September 1999 until August 2000. This yielded 57 titles. There might have been a bias in this way of gathering information, but it gives an impression of the kind of subjects that are in vogue with the general Dutch audience. It is not clear whether these results are representative for other Western countries, but it is obvious that many of the American successes on the reader market are being translated and find their way to a Dutch and other audiences.

The best-selling psychology books are sorted on the basis of the first impression the books make on buyers in a bookstore. Two investigators looked at the title, the cover, the texts on the back and read the first few pages. The categorization was based on the central message of the publisher and author(s) for the potential reader. The present author made an ad hoc categorization, and a second rater was used to check the inter-rater reliability for the classification, which was satisfactory (r = 0.86).

There is a chance that this procedure does not do justice to the scope of subjects that the authors cover, but on the other hand the messages of the self-help authors are very straightforward. Examples of titles are: I can think and feel what I want (Diekstra) Men are from Mars, women are from Venus (Gray) and Don’t worry, make money (Carlson).

Growth

The first category is ‘personal growth’. It is about the improvement of the self. Other phrases that cover this category are personal efficiency, self-management, art of living and ways to reach your goals. The books are about feeling better and living better. This was by far the largest category with 19 books out of the top 57. One should notice that in most other books self-improvement is an important theme as well, but in those other books the theme is addressed more indirectly.

Relationships

The second category is ‘personal relations’. This category (nine books) focuses on intimate relationships and has an overlap with the category Communication (five books). The difference is that the first category is more goal-oriented (having satisfying relationships) while the second tries to offer tools to understand and enhance communication abilities. These communication skills can be used for intimate relationships, and in other settings as well.

Coping

The third category is ‘coping with stress’. These books provide practical ideas on how to find relaxation and rest, in particular in relation to working life. Another theme in this category is to enhance resilience in difficult circumstances. The authors offer interventions that have a cognitive behavioral signature. They help readers to develop an outlook at the world that minimizes stress. This category contains eight books.

Identity

The last substantial category is ‘Who am I?’ It contains six books. This section has a large overlap with the Personal growth category, and this overlap was responsible for most of the disagreement between the two raters. Knowing thyself can be thought of as the first step for making the right choices in life and for self-improvement. The difference is that the category ‘Who am I?’ is more oriented towards providing insight and the category Personal growth is more practical. Self-improvement is a secondary goal for the category ‘Who am I?’ However the distinction remains somewhat problematic. For example Goleman’s book about emotional intelligence is insight oriented, but is categorized on the basis of a first impression under the heading Personal growth. The Dutch cover mentions as the subtitle that emotions offer a ‘key to success’.

Self-help is dominant in bookstores

All categories of the psychology books mentioned in Table 1 fall into the self-help category except the categories psychotherapy, psychological tests, study-books, (auto)biographies and fiction. The books about psychological tests and psychotherapy are not considered self-help, because they do not help readers to improve or heal themselves, but tell them what to expect when they are tested or receive psychological treatment. The study-books are meant for students and aim at transfer of knowledge. The (auto)biographies and fiction books are not aimed directly at self-help, although the stories may be inspirational. An exception is the autobiographical book by Bergen in which the author describes her own burnout and offers advice for better ways of dealing with stress. Therefore this book is also mentioned under the header stress. Forty-eight out of fifty-seven best selling psychology books fall under the heading self-help.Footnote 2

Two dimensions of self-help

The thematic categories are still too broad fur further analysis of the effectiveness of the advice offered. Therefore we divided the group further using two dimensions. The books can be problem-focused or growth-oriented and can be theory-guided or eclectic. The first dimension roughly follows the categories used above. The categories Personal growth and Who am I? are clearly growth-oriented and the categories Coping with stress, Depression and Sleep are problem-oriented. The other categories or more heterogeneous or fall in the middle of the dimension.

Eclectic self-help books use ideas from different schools of thought in psychology; theory-guided books translate ideas from one particular research tradition so that they are suitable for a large audience. Most books are eclectic in nature, but more academically oriented authors often write theory-guided books. Examples are the work of Seligman, Csikszentmihalyi and Bolen. Seligman and Csikszentmihalyi are among the founders of the school of positive psychology and Bolen is a Jungian scholar. The ideas of cognitive behavioral psychotherapy is well represented among the theory-guided self-help books.

A surprise might be that the growth-oriented books outnumber the problem-oriented books. In the top 57 of best-selling psychology books there is only one book about overcoming depression and no books that specifically target anxiety disorders or addiction. This could be an artifact of the method used for this selection of self-help books. Our sample was based on the books sold in general bookstores, and self-help books are also distributed by mental health professionals and client organizations. For example the book In de put uit de put (Feel bad feel good), a Dutch adaptation by Cuijpers of the anti-depression book by Lewinsohn et al. (1986), sells well in the Netherlands, but is distributed outside bookstores in mental health centers (Cuijpers, personal communication). The guided use of self-help books is sometimes described in the literature as ‘minimal contact psychotherapy’.

The scarcity of best-selling books about psychological disorders in the Netherlands may indicate that people with mental disorders need the guidance of a professional before trying a self-help book. People that seek to enhance their communication skills or their ability to cope with stress do not need such professional support. Perhaps people with mental disorders think that their problems are too serious to be solved by a self-help book. Another explanation is that they might misdiagnose their own problems. Somebody with social phobia might buy a book about communication skills and somebody with a depressive disorder might buy a book to enhance personal relationships.

Readership

What type of people buy self-help books? There is not much research available to answer this question, but Starker (1989) thinks that self-help is an essential part of American culture. Self-help books started more than 200 years ago with a new conception of society based on what Jefferson called the individual ‘pursuit of happiness’ in the Declaration of Independence. The rigid, fixed-class systems of European countries were replaced by an open system in which ‘a man could hope to rise in station according to his merits and abilities, and to be judged solely on the basis of his individual accomplishments’ (Starker 1989, p 169). Obstacles to upward social mobility were removed and people felt that they also could be part of the American dream, if only they would know how. Self-help books offered appropriate guidance. This individualistic background is also recognizable in most of the self-help books that sell well in the Netherlands. There is no reason to think that the people that buy this kind of self-help book are typically chronically unhappy or mentally disturbed. Wilson and Cash (2000) conducted a survey of a sample of 264 college students. Females were more likely to have a positive attitude towards self-help books. Other factors that predicted a positive attitude to self-help books were: enjoyment of reading in general, psychological mindedness (the disposition to think about psychological processes as related to the self and to relationships), a stronger self-control orientation and, last but not least, a greater life satisfaction. Self-help readers tend to have an ability to recognize relationships between thoughts, feelings and actions and want to use self-help books to improve themselves. Reading self-help book seems to be part of an active and adequate coping style, which fits in with an individualistic culture, where individuals have the freedom to pursue happiness on there own ground.

As for the Netherlands the profile of the readers of the Dutch monthly Psychology Magazine is known. We do not suspect that the readers of this magazine differ much from the people that buy self-help books in general. Psychology Magazine often has headlines with practical implications on the cover, such as how to be happy, how to succeed in relationships or how loneliness can be overcome.

Table 3 shows that the readers of Psychology Magazine are relatively well-to-do and highly educated. They work in a wide range of professions. Unfortunately we have no information about the mental health of readers. But we do know that they are very curious. The readers have indicated that they have a more than average interest in a wide range of subjects, ranging from developmental aid, literature, art history, medical science and vegetarian diets. Vegetarianism is even more interesting for the readers than psychology (Weekbladpers Tijdschriften, 2004, Unpublished paper). Such a lively interest in different subjects is more characteristic of happy than unhappy individuals (Veenhoven, 1988).

The effects of reading self-help books

Do self-help books help? There are good reasons to doubt it. Yet there are also good reasons to expect that they often do. Below we review the arguments.

Misgivings about self-help books

There is a lot of cynicism about the effectiveness of self-help books. It is not uncommon to bash self-help as a whole. Macdonald (1954) writes: ‘How to writers are to other writers as frogs are to mammals; their books are not born, they are spawned. A howtoer with only three or four books to his credit is looked upon as sterile.’ Rosen (1977) used the title ‘Psychobabble’ in his volume on this topic. He writes: ‘Psychobabble is... a set of repetitive verbal formalities that kills off the very spontaneity, candor, and understanding it pretends to promote. It’s an idiom that reduces psychological insight to a collection of standardized observations, that provides a frozen lexicon to deal with an infinite variety of problems.’ Styron (1990) calls self-help books fraudulent. Csikszentmihalyi (1999, p. 20) claims it is apparent self-help books will not help most readers to be thin, powerful, rich and loved; and even if they succeed the readers will still be as unhappy as before they read the book. Polivy and Herman (2002) claim that buying self-help volumes must be part of a false hope syndrome. Salerno (2005) holds self-help responsible for the end of romance, soaring divorce rates, the decline of the nuclear family, excessive political correctness and rising substance abuse, although this is by quite an inferential leap (Weiten, 2006).

Specific techniques recommended by self-help authors

Such a negative attitude is not justified by reference to any empirical studies. We were not able to find any studies that empirically investigated the effectiveness of the best-selling self-help books in the Netherlands. However, there are indications that self-help books sometimes offer outdated advice.

Paul (2001) describes five common self-help myths:

-

Vent your anger, and it will go away. Research shows that expressing anger can keep it alive.

-

When you are down in the dumps, think yourself happy by focusing on the positive. Research shows that the result may be the opposite of what you want. It can make your misery of the moment even more apparent.

-

Visualize your goals; it will help you to make them come true. Research shows that we not only need optimism about our ability to reach a given goal, but also a sharp focus on the obstacles that are in the way. You need to pay attention to the obstacles and the necessary steps to reach the goal.

-

Self-affirmation will help you raise low self-esteem. Research shows that this technique is not powerful enough. We need positive feedback from people that matter to us. ‘Self-esteem is the sum of your interactions with others over a lifetime, and it’s not going to change overnight’.

-

Active listening can help you communicate better with your partner. This is an appealing idea, but research shows that even happy, loving couples don’t use the technique. It may be better to take your partner seriously, to avoid hostility and to avoid arousal.

Paul (2001) concludes: ‘The five distortions presented here are only a few of the misconceptions you may encounter. To protect yourself against others, be sure to take the self-help descriptions with a measure of skepticism and a healthy dose of common sense.’ The myths Paul (2001) describes confirm the mixed picture of the best-selling self-help books that emerged from the ratings by clinicians and make clear that self-help is not as good as it can or should be.

Another technical limitation is that self-help books work with a ‘one-size fits all’ approach. The advice is not be tailored to the personality of the reader, diagnosis or personal circumstances. Norem and Chang (2002) relate that this is a flaw that is also apparent in the positive psychology movement that is gaining momentum. They emphasize this point by a discussion of optimism. It is tempting to conclude that it is wise to enhance optimism as much as possible, because there is substantial evidence that optimism in its many forms leads to better outcomes in coping, health, satisfaction and well-being (Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 2001). Still, the recommendation to look at the bright side is counterproductive for people who are very anxious. The induction of a positive mood deteriorates their performance and satisfaction. For them a strategy that is called defensive pessimism yields better results (Norem, 2001). Defensively pessimistic individuals set themselves unrealistic low targets and devote considerable time to all the possible outcomes they can imagine for a given situation. The result is twofold: on the one hand they no longer have to fear that they will mess up, because this is what could be expected; the other result is an increase in motivation. They know what might happen. The end result is a good performance, which would have been threatened by imposed optimism.

Another question is what aspect of optimism is lacking for a certain individual. Aspinwall, Richter and Hoffman (2001) illustrate this by the serenity prayer. Most psychologists studying optimism focus on changing the things one can change through active coping, and self-help authors are hard-liners in this respect. But Aspinwall, Richter and Hoffman offer data that indicates that the other parts of the prayer are equally important: it is productive to accept the things one cannot change and to have the wisdom to distinguish things one can and cannot change. Self-help may have detrimental effects if it focuses on the wrong aspects of optimism for a certain reader.

‘The challenge for positive psychology as it works to better the human condition is to remember that there is no one human condition’ (Norem & Chang, 2002). The same is true for self-help. Solid, empirically valid self-help advice about learned optimism (Seligman, 1991), that is strongly recommended by clinicians (Norcross et al., 2000), may have negative consequences for some of the more anxious readers.

Observed effects of reading problem-focused books

There is empirical evidence that reading problem-focused self-help materials can be effective in the treatment of disorders, and even have outcomes comparable to therapist administered treatments (Wilson & Cash, 2000; Den Boer, Wiersma, & Van Den Bosch, 2004). For example Cuijpers (1997) has made a meta-analysis of six studies in which the effectiveness of bibliotherapy was compared with other treatment modes for unipolar depression. The author’s conclusion is described and updated in the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness; “Bibliotherapy is an effective treatment modality, which is no less effective than individual or group therapy.” The treatment effect was measured with the help of depression inventories. A more elaborate review yields the same conclusion (Cuijpers, Kramer, & Willemse, submitted). Self-help books can also prevent part of the incidence of depression in high risk groups (Willemse, Smit, Cuijpers, & Tiemens, 2004).

Cuijpers (1997) conclusion about the effectiveness of the self-help books is based on a limited number of studies and the participants were not drawn from a clinical population, but were recruited through announcements in the media. The depressions were mild more often than severe. Other reviews on the effectiveness of bibliotherapy also suggest that reading instructions can have significant positive consequences, better than control treatment while on a waiting list (Den Boer, Wiersma & Van Den Bosch, 2004; Gould & Clum, 1993; Mains & Scogin, 2003; Marrs, 1995; Scogin, Bynum, Stephens & Calhoon, 1990; Williams, 2001).

However, it is clear that self-help is not equally effective for each disorder and every person. According to Mains and Scogin (2003), self-help treatments were successful for anxiety, depression and mild alcohol abuse, but less so for smoking cessation and moderate and severe alcohol abuse. Gould and Clum (1993) and Marrs (1995) add successes for headaches, insomnia and sexual dysfunction, and confirm the lack of success for smoking cessation and alcohol addiction. Self-help has greatest success with people with high motivation, resourcefulness and positive attitudes toward self-help treatments.

There are also several studies that failed to find positive effects from self-administered treatment programs, even if the technique prescribed has been shown to be successful in a psychotherapeutic context (Rosen, 1987; Rosen, Glasgow, & Moore, 2003). The fact that empirical data about the efficacy of most self-help books is lacking, must be taking seriously given the cautionary tale by Rosen (1987). He probably has the honor to have reached the largest experimental effect ever in psychotherapy literature, but sadly in the wrong direction. He studied a self-help desensitization program for people with a snake phobia. The program worked fine for people that complied to it, but only 50% did. So the researchers added a self-reward strategy to their program to enhance compliance, but discovered that compliance dropped to zero, an unexpected failure from well-intending experts with state-of-the-art knowledge.

Another cautionary remark is that the power of a book to lead to meaningful changes in thinking, feeling and behavior, can also have negative consequences. A famous example is Goethe’s book Die Leiden des jungen Werthers (1774) that is said to have inspired some readers to commit suicide. Failure to benefit from a self-help book may lead to self-blame and/or the worsening of symptoms (Rosen, 1987). An as yet unpublished study indicated that people that read a self-help book about depression with minimal help from a psychotherapist, wrongly concluded that they could not be helped at all if they did not profit from the advice offered (De Regt, personal communication); but empirical research suggests that these negative consequences are rather rare (Scogin, et al., 1996).

Indications for effectiveness of reading growth-oriented books

The effectiveness of growth-oriented self-help books has not yet been investigated in this way. There are, however, some indications of their effectiveness. One indication is the judgement of these books by professionals and another is the readers’ evaluations. Still another indication for effectiveness is the relevance of the topics addressed. Below we will check that relevance in a comparison of topics in the books and the conditions for happiness observed in empirical research.

Clinicians’ ratings of self-help books

The Authoritative guide to self-help resources in mental health (Norcross et al., 2000) has brought together the reviews and ratings of more than a thousand American clinicians about 600 self-help books for different categories like schizophrenia, mood disorders, anxiety, stress-management and headaches. The problem-focused books are dominant, but some of he categories such as Career development, Self-management and self-enhancement and Spiritual and Existential concerns are clearly growth oriented.

The selection of self-help books was not random, but it is encouraging that the reviews are predominantly positive. Nineteen percent of the books are considered very helpful and one percent is rated negative. Another indication for the quality of self-help books is the fact that a large number of psychotherapists (85%) recommend self-help books to clients (Campbell & Smith, 2003; Norcross et al., 2000; Starker, 1988).

Thirteen books out of the top 57 bestselling Dutch psychology books were rated in Norcross et al. (Table 4). The ratings are rather mixed. The main reason for this is that the books by Wayne Dyer and John Gray are often sold to the Dutch public, although clinicians do not recommend them.

Readers’ evaluations of self-help books

Starker (1989) conducted a survey on self-help of 67 volunteer hospital workers, men and woman ranging in age from 27 to 86 years of age. Starker did not make a distinction between problem focused and growth oriented self-help books for his survey. The large majority (85%) thought the books were ‘sometimes helpful’ or ‘often helpful’. This sample reported positive experiences such as:

-

‘Opened new avenues for me’.

-

‘More self-confidence’.

-

‘Made me understand myself and others’.

-

‘Insight into problem areas’.

-

‘Peace of mind’.

-

‘Knowledge of hypertension and stress’.

Relevance of the advice

Self-help books are unlikely to be effective if the topics they address have little relevance for the happiness of most people. This can be checked by comparing the topics in growth-oriented books with findings of empirical research on happiness. If a self-help author recommends to seek happiness in a higher income, that advice is unlikely to work out well for most readers, since research has found little relation between happiness and income (e.g., Kasser, 2002; Ryan & Dziurawiec, 2001; Tatzel, 2003). If, however, the advice is to optimize personal relationships, an effective book has a good chance to enhance happiness, because good relationships appear to be an important condition for happiness.

This line of reasoning offers the possibility to check the topic choices in the self-help literature. Because of the abundance of the studies involved I will not use individual studies, but refer again to the findings in the World Database of Happiness (Veenhoven, 2006). This is a large database were most correlational findings about happiness are gathered. Table 5 summarizes the topic choices in the self-help literature and makes a comparison with the correlational data in the database.

Table 5 confirms the impression that self-help books recommend for things that are related to happiness. The differences between the recommendations in self-help-books and the observed correlates of happiness do not seem to be random.

The self-help books stress a specific way of life that is built on the ideas of the individual pursuit of happiness and humanistic psychology. In self-help books the focus is more on eudemonic well-being than on hedonistic well-being. These concepts offer different definitions of the good life. Hedonistic well-being concentrates on pleasure attainment and pain avoidance, on feeling good, but not necessary on outward success. Eudemonic well-being defines well-being in terms of the degree to which people are fully functioning (Ryan, 2001) and adds a moral dimension to the good life.

The authors want to foster personal growth and overrate personal independence, tolerance, self-actualization, calmness and an internal locus of control. Aggression, popularity and appearance seem to be undervalued. So self-help books could help to enhances happiness. However, this content-analysis cannot give an indication whether these self-help books actually fulfil their promise.

Similarities and differences with psychotherapy

A comparison with psychotherapy research can help to get a more complete view on the possible effects of reading self-help books. A useful distinction in psychotherapy research is the difference between specific and non-specific effects. This distinction was made because of the unexpected fact that very different schools of psychotherapy (psychodynamic, humanistic or behavioral) tend to yield the same treatment outcomes. Luborsky, Singer and Luborsky (1975) suggested to use the verdict of the Dodo bird in Alice in Wonderland: ‘Everyone has won and all must have prizes.’

This effect can be explained by common factors in psychotherapy, like the personal resources and life circumstances of the client (which explain 40% of outcome variance), the emotionally charged relationship with the therapist (30%) and placebo, hope and expectancy (15%). The specific techniques and models of the treatment may explain 15% of treatment variance (Hubble & Miller, 2004). Below, self-help is discussed with the help of the three common factors, that are most relevant for treatment outcome.

Hope, placebo and expectancy

An important common factor that is shared by virtually all self-help books is the message that you can improve your lot. They offer a strong antidote against learned helplessness (Seligman, 1975), but perhaps for readers that do not suffer from it. Starker (1989) is an outspoken defender of this common factor. He writes:

Of what value is an inspirational message to those in need of health, beauty, happiness, success, and creativity? In general, it lifts the spirit, engenders and supports hope, and keeps people striving towards their goals; it also fends off feelings of helplessness, hopelessness, despair and depression. This constitutes its greatest service. When a particular self-help book loses its value in this regard, when it is ‘used up’ as a source of inspiration and motivation, it is generally discarded and replaced. Readers become bored or disillusioned with particular self-help works and technologies, but seem to be quite forgiving of the genre. Perhaps the next book will provide the answers, the comfort, the cure, the secrets being sought.

Starker goes on to compare the effect of self-help books with a placebo effect for drugs. He quotes Linnie Price: “If the pharmaceutical industry were to produce a drug which was as reliable, of such wide-ranging applicability, and with a record of efficacy as impressive as that of the placebo effect, it would be no doubt be proclaimed a miracle panacea.” The belief that one can improve is a powerful factor in actual improvement, and cannot easily be dismissed. Ogles, Lambert & Craig (1991) found that reading a self-help book about coping with loss or divorce resulted in higher symptomatic relief for readers with higher initial expectations of benefit.

This inspirational message comes with a risk. Active coping can lead to frustration if it is impossible to control a stressor. It may inspire persons to blame themselves for things that occur to them outside their responsibility. Sometimes acceptance may be a better way out than active coping, and sometimes cultural change may be necessary instead of individual change.

Rosen (1987) points to the fact that the inspirational message can lead to unsubstantiated and exaggerated claims. He takes a book by the noted psychologist Arnold Lazarus as an example. On the jacket of his book In the Mind’s Eye, it is claimed that the book will help to ‘enhance your creative powers; stop smoking, drinking or overeating; overcome sadness and despondence; build self-confidence and skill; overcome fears and anxiety’. This is quite a claim for an untested book and not in line with the APA ethical standards: ‘Psychologists do not make (...) deceptive (...) statements concerning (...) the degree of success of, their services.’ (http://www.apa.org/ethics) Other books exaggerate even more, as is the case with the book title of Diekstra: ‘I can think and feel what I want.’ This is unethical by APA standards; and the risk of exaggerated claims is that they foster disappointment.

Another danger of overly optimistic messages is that readers will take a lighthearted attitude to meaningful changes. In psychotherapy it is commonly recognized that effort is necessary for improvement and/or relapse prevention. The self-help message that the wisdom of an author guarantees heaven on earth may inspire daydreaming, but not hard work and perseverance (Ellis, 1993). For example, it has been shown that women who fantasized about size 36 that they would reach with the latest diet, actually gained weight, if they didn’t pay proper attention to all the obstacles on the way and didn’t realize how much willpower they would need in order to stick to the diet (Oettingen, 1996).

The role of a professional

The relationship between the client and the therapist is an important factor in explaining the successes of therapy (Wampold, 2001), and this element is obviously missing in self-help. The role of the psychotherapist is mentioned here explicitly, to highlight the fact that self-help lacks the involvement of a professional. In psychotherapy it is not only the client that chooses the therapist, but also the therapist that chooses a client and selects a treatment. This selection process can make the difference between treatment success and failure, but in self-help it is the reader who has to make a choice on his or her own.

It is important to notice that self-help readers are not provided with a structure to overcome this limitation. Academic psychology usually neglects the genre and leaves it to the public to make choices. Publishers and authors have a stake in selling many books and try to persuade as many readers as possible to buy the book. We have never seen a self-help book with contra-indications on the cover or a warning about possible side effects.

Starker (1989) thinks that the enormous variety of self-help books and the haphazard way in which they are selected represents the ‘greatest single problem’ with the genre. A well-advertised book that is endorsed by a celebrity will find a larger audience than a better book from a small publishing house. The danger that the mismatch between a reader and the technology offered in a self-help book has negative consequences is probably greater if the book is highly prescriptive and if the author presents a closed philosophy that discourages the reader to look for corrective information.

The role of the reader

The discussions about the lack of involvement of a therapist and the interaction between the advice offered and the personality of the reader, make it clear that in self-help the client bears a lot of responsibility in choosing a suitable self-help book and after this choice has been made, in sorting out the options that are presented by the self-help author.

The interaction between the advice offered and the personality or circumstances of the reader can in principle be studied and data about this can be used for the advantage of the reader. But the interaction between reader and book goes much further than that and will also have more unpredictable aspects. No self-help guide can offer a real recipe for the good life. A book can only point to possible directions. The reader will decide which leads he or she will follow and which can be ignored. Another possibility is that the reader will misunderstand the author. The advice will also be applied in situations for which it was never intended. Therefore it is likely that in some cases good advice can lead to bad outcomes and bad advice may work out fine.

A self-help book requires a very active role on the part of the reader, but maybe this is not that different from the situation in psychotherapy. Hubble and Miller (2004) describe clients as full and complete partners in their care. They suggest that psychotherapists should adopt the frame of reference of clients themselves to make meaningful changes and should above all help clients to discover their own strengths and use them more often.

In self-help the role of the reader is even more important. Maybe the self-help books function in a way that is similar to travel guides. Most readers will not follow the book page by page, but will study parts of the book and will select some travel options they would have never heard of without the book. In a similar way self-help books seem to enhance the freedom of choice in an individualistic society. The books show options for thinking and acting from the psychological toolkit of the individual that are underdeveloped or could be used more often. Perhaps we may trust the readers to use the advice as long as it helps for them. This optimism is greatly enhanced by the fact that individuals flourish more in individualistic and free societies (see for reviews Veenhoven, 1998, 1999). Most individuals are apparently able to choose options in life that work for them.

If this interpretation is correct, we can speculate that the quality of the advice offered in self-help books may be less important than the quality of the reader. It is the reader that decides to drop the options that do not enhance satisfaction and keep on track if some advice seems to work out fine. If a self-help therapy works we should first congratulate the ‘client’ not the ‘therapist’.

Conclusion

There is some evidence that reading problem-focused self-help books tends to be helpful for people with specific problems. As yet there is no hard evidence for the effectiveness of reading growth-oriented books. This is a regrettable omission on the part of academic psychology.

Notes

Warnyta Koedijk, uitgeverij Kosmos Z&K, Utrecht.

Some authors may object to the loose classification of self-help used in this paper. For example, one of the anonymous reviewers of this paper mentioned that Csikszentmihalyi would be horrified to see his work classified as self-help. Csikszentmihalyi’s work is a long shot from the superficial quick fixes that are characteristic for part of the self-help literature, and the quality of his work is excellent judged by academic standards. His work is more descriptive than practical (Seligman, 2002). However, the sub-title of his book Flow is the ‘the psychology of optimal experience’ and it should come as no surprise that readers will buy this book, partly because they want to experience this optimum more often for themselves.

References

Aspinwall, L. G., Richter, L., & Hoffman, R. R. (2001). Understanding how optimism works. In E. C. Chang (Ed.), Optimism and pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Campbell, L. F., & Smith, T. P. (2003). Integrating self-help books into psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59, 177–186.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). Flow: Psychologie van de optimale ervaring. Amsterdam: Boom.

Cuijpers, P. (1997). Bibliotherapy in unipolar depression: a meta-analysis. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 28, 139–147.

Cuijpers, P., Kramer, J., & Willemse, G. (submitted). Minimal contact therapy for depression.

Den Boer, P. C., Wiersma, D., & Van den Bosch, R. J. (2004). Why is self-help neglected in the treatment of emotional disorders? A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 34, 959–971.

Diekstra, R., & McEnery, G. (2001). Het verdriet voorbij; herziene editie. Rijswijk: Elmar.

Ellis, A. (1993). The advantages and disadvantages of self-help therapy materials. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 24, 335–339.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional intelligence. New York: Bantam Books.

Gould, R. A., & Clum, G. A. (1993). A meta-analysis of self-help treatment approaches. Clinical Psychology Review, 13, 169–186.

Hubble, M. A., & Miller, S. D. (2004). The client: Psychotherapy’s missing link for promoting a positive psychology. In P. A. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.), Positive psychology in practice. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Kasser, T. (2002). The High Price of Materialism. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kramer, P. D. (1997). Should You Leave? A Psychiatrist Explores Intimacy and Autonomy - and the Nature of Advice. New York: Scribner/Simon & Schuster.

Lazarus, A., & Lazarus, C. N. (1997). The 60-second shrink: 101 strategies for staying sane in a crazy world. San Luis Obispo, CA: Impact Publications.

Lewinsohn, P. M., Munoz, R. F., Youngren, N. A., & Zeiss, A. M. (1986). Control your depression. New York: Prentice Hall.

Luborsky, L., Singer, B., & Luborsky, L. (1975). Comparative studies of psychotherapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 32, 995–1008.

Macdonald, D. (1954). Howtoism, New Yorker, 22 May: 82–109.

Mains, J. A., & Scogin, F. R. (2003). The effectiveness of self-administered treatments: A practice-friendly review of the research. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59, 237–246.

Marrs, R. W. (1995). A meta-analysis of bibliotherapy studies. American Journal of Community Therapy, 23, 843–870.

Meyer, D. B. (1980). The positive thinkers; Religion as pop psychology from Mary Baker Eddy to Oral Roberts. New York: Pantheon Books.

Norcross, J. C., Santrock, J. W., Campbell, L. F., Smith, T. P., Sommer, R., & Zuckermann, E. L. (2000). Authoritative guide to self-help resources in mental health. New York: Guilford Press.

Norem, J. K. (2001). Defensive pessimism, optimism, and pessimism. In E. C. Chang (Ed.), Optimism and pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Norem, J. K., & Chang, E. C. (2002). The positive psychology of negative thinking. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(9), 961–964.

Oettingen, G. (1996). Positive fantasy and emotion. In P. Gollwitzer & J. A. Bargh (Eds.), The psychology of action. Linking cognition and motivation to behavior. New York: Guilford.

Ogles, B. M., Lambert, M. J., & Craig, D. (1991). A comparison of self-help books for coping with loss: Expectations and attributions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 38, 387–393.

Paul, A.M. (2001). Self-Help: Shattering the Myths. Psychology Today, March.

Peverelli, H. (1999). Hoe goed is de internet-psycholoog? (Can you trust the internet psychologist?). Psychologie Magazine, May.

Polivy, J., & Herman, P. (2002). If at first you don’t succeed; false hopes of self-change. American Psychologist, 57(9), 677–689.

Rabasca, L. (2000). Self-help sites; A blessing or a bane. Monitor on Psychology, 13, 4.

Rosen, R. D. (1977). Psychobabble; Fast talk and quick cure in the era of feeling. New York: Atheneum.

Rosen, G. M. (1987) Self-help treatment books and the commercialization of psychotherapy. American psychologist, 42, 46–51.

Rosen, G. M., Glasgow, R, & Moore, T. E. (2003). Self-help or hype? The science and business of giving psychology away. In S. Lilienfeld (Ed.), Science and pseudoscience in contemporary clinical psychology. New York: Guilford.

Ryan, L., & Dziurawiec, S. (2001). Materialism and its relationship to life satisfaction. Social Indicators Research, 55(2), 185–197.

Ryan, M. R. (2001). On happiness and human potentials; A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–167.

Salerno, S. (2005). SHAM: How the self-help movement made America helpless. New York: Crown Publishers.

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (2001). Optimism, pessimism, and psychological well-being. In E. C. Chang (Ed.), Optimism and pessimism: Implications for theory, research, and practice. Washington D.C.: American Psychological Association.

Scogin, F., Bynum, J., Stephens, G., & Calhoon, S. (1990). Efficacy of self-administered treatment programs: meta-analytic review. Professional Psychology: research and practice, 21, 42–47.

Scogin, F., Floyd, M., Jamison, C., Ackerson, J., Landreville, P., & Bissonnette, L. (1996). Negative outcome: What is the evidence on self-administered treatments? Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64, 1086–1089.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1975). Helplessness; on depression, development and death. San Francisco: Freeman.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1991). Learned optimism: The skills to conquer life’s obstacles, large and small. New York: Random House.

Seligman, M. E. P. (1994). What you can change and what you can’t: The ultimate guide to self-improvement. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Gelukkig zijn kun je leren (Authentic happiness). Utrecht: Het Spectrum.

Starker, S. (1988). Do-it-yourself therapy; The prescription of self-help books by psychologists. Psychotherapy, 25, 142–146.

Starker, S. (1989/2002). Oracle at the supermarket; The American preoccupation with self-help books. New Brunswick: Transaction Publishers.

Steiner, C., & Perry, P. (1997). Achieving emotional literacy; A personal program to increase your emotional intelligence. London: Bloomsbury.

Styron, W. (1990). Darkness visible. New York: Random House.

Tannen, D. (1986). That’s not what I meant( How conversational style makes or breaks relationships. New York: Ballantine.

Tannen, D. (1990). You just don’t understand. New York: William Morrow and Co.

Tatzel, M. (2003). The art of buying: Coming to terms with money and materialism. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4, 405–435.

Veenhoven, R. (1988). The utility of happiness. Social Indicators Research, 20, 333–354.

Veenhoven, R. (1998). Freedom and happiness; A comparative study in 44 nations in the early 1990’s. In E. Diener & E. Suh (Eds.), Subjective well-being across cultures. Cambridge MA: MIT Press.

Veenhoven, R. (1999). Quality-of-life in individualistic society; A comparison of 43 nations in the early 1990’s. Social Indicators Research, 48, 157–186.

Veenhoven, R. (2006). World Database of Happiness: Continuous register of research on subjective appreciation of life. Website at Erasmus University Rotterdam, http://www.eur.nl/fsw/research/happiness.

Wampold, B. E. (2001). The great psychotherapy debate: Models, methods, and findings. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Weiten, W. (2006). A very critical look at the self-help movement; A review of SHAM: How the self-help movement made America helpless by Steve Salerno Psycritiques, 51, 2.

Willemse, G. R., Smit, F., Cuijpers, P., & Tiemens, B. G. (2004). Minimal-contact psychotherapy for sub-threshold depression in primary care. Randomised trial. British Journal of psychiatry, 185, 416–421.

Williams, C. (2001). Use of written cognitive-behavioural therapy self-help materials to treat depression. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment, 7, 233–240.

Wilson, D. M., & Cash, T. F. (2000). Who reads self-help books? Development and validation of the self-help reading attitudes survey. Personality and Individual Differences, 29, 119–129.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix A

Appendix A

Best-selling psychology books

Albom, Dinsdagen met Morrie.

Baanders, Ik ben niet verdrietig, ik ben boos.

Bakker, Vitaliteit.

Ball, Droomencyclopedie.

Beggs, Kleine boek van de inspiratie.

Benninga, Haal het beste uit jezelf.

Bergen, Lessen van burn-out.

Bloemers, Psychologisch onderzoek.

Bolen, Goden in elke man.

Bolen, Godinnen in elke vrouw.

Can, Leren omgaan met je depressie pakket.

Carlson, Don’t worry, make money.

Carlson, Maak van een mug geen olifant op het werk.

Carnegie, Zo maakt u vrienden en goede relaties.

Cleese, Hoe overleef ik mijn familie.

Csikszentmihalyi, De weg naar flow.

Csikszentmihalyi, Flow.

Delfos, Luister je wel naar mij?

Diekstra, Ik kan denken voelen wat ik wil.

Diekstra, O Nederland Vernederland.

Dyer, Beziel je leven.

Dyer, Geen zee te hoog.

Dyer, Geschenken van Eykis.

Dyer, Niet morgen, maar nu.

Elias, Emotionele intelligentie voor ouders.

Fever, Pak van mijn hart.

Forward, Emotionele chantage.

Goleman, Emotionele intelligentie.

Gottman, Zeven pijlers van een goede relatie.

Gray, Krijgen wat je wilt en willen wat je hebt.

Gray, Liefdesgeheimen van Mars en Venus.

Gray, Mannen komen van Mars, vrouwen van Venus.

Gray, Mars en Venus beginnen opnieuw.

Gray, Mars en Venus krijgen een kind.

IJzermans, Beren op de weg, spinsels in je hoofd.

Karsten, Omgaan met burn-out.

Knoope, De creatiespiraal.

Lang, Psychologische gespreksvoering.

Lundberg, Problemen laten bij wie ze horen.

MacGraw, Leer te leven.

Millman, Keerpunt in je leven.

Millman, Leven waarvoor je geboren bent.

Norwood, Als hij maar gelukkig is.

Pease, Waarom mannen niet luisteren.

Powell, Zelfhypnose voor iedereen.

Rigter, Palet van de psychologie.

Robbins, Je ongekende vermogens.

Sterk, Denk je sterk, denk je zeker.

Sterk, Ruimte voor jezelf.

Vanzant, In de tussentijd; Vind jezelf en de liefde die je nastreeft.

Wijnberg, Als je zegt wat je denkt.

Wilson, Grote boek van de rust.

Wilson, Kleine boek van de rust.

Wilson, Kleine boek van de slaap.

Wilson, Kleine boek van het geluk.

Young, Leven in je leven.

Zohar, Spirituele intelligentie.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Bergsma, A. Do self-help books help?. J Happiness Stud 9, 341–360 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9041-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9041-2