Abstract

A case study of 20 families investigated a cluster design of new homes for 15 adults with intellectual disabilities in Australia. It explored how families created a cluster home model for adults to live in their own homes with paid support in a modern context by answering three research questions: What type of home did parents choose for their children with intellectual disabilities and why? What type of home did they achieve? How did they overcome challenges to accomplish building the home? Families adopted a participatory design approach, collaborating as learning partners to secure government funding for purchasing land and constructing their cluster design. However, it was a complex project requiring many stakeholders with conflicting interests and priorities. Specifically, families rejected the group home model preferred by government agency staff, shifted the focus from technical building rules and design standards to prioritise each adult’s needs and preferences for their home, rejected institution-like fixtures/fittings when installed and used family governance to choose key support workers directly. Ultimately, the families created security of place through tenancy in attractive homes with government funding, welcoming neighbours and chosen support workers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Many people with intellectual disabilities in Australia have lived with and been cared for by families and friends since birth. Community living in group homes, boarding homes and nursing homes (Clement & Bigby, 2010) were developed to replace large residential centres operated or funded by state and territory governments. However, group homes were the main alternative to family homes for supported accommodation for people with intellectual disabilities when families or friends were not an option. The New South Wales (NSW) Government (2006) reviewed accommodation and support funding, reporting that almost half of its disability budget funded care, including supported accommodation for just 3% of the cohort who received government-funded services. Progress towards more person focused individualised housing for people with significant and permanent disabilities – which advocates and researchers had long called for, and Australia’s 2008 commitment to the UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (United Nations, 2006) requires – culminated in the introduction of Australia’s National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in stages from 1 July 2013 and the National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013 (Cth) (Madden et al., 2013; Stubbs et al., 2020).

This article examines a unique case study selected from 11 doctoral investigations (the ‘doctoral research’) of new homes created by parents or non-government organisations for adults with disability taking action to improve their housing and support options. Housing systems in NSW have frequently excluded adult children living with parents from government-funded housing and applying for housing (as found in the doctoral research and Earl, 2007), which would otherwise help them move into independent living arrangements. The Ryde Area Supported Accommodation for Intellectually Disabled Inc (RASAID) case is unique because RASAID families successfully secured NSW Government funding to purchase land and Australian Government funding to build innovative cluster housing on a single large site for 15 adults (the ‘residents’) by working together from 2004 to 2016. Further, the families collaborated with key politicians who acknowledged the need for housing and committed government funding. Indeed, the research participants (RP) shared that the then Minister for Disability Services (NSW), the Hon Andrew Constance, stated that governments and other families could learn from the outcomes for adults with different types of disability living with friends and peers in the cluster.

The families’ and residents’ involvement in selecting and designing characteristics of the completed home environment was equally unique. Rapoport (1985, p. 256) explained that choice is the central characteristic of the home environment, contending that characteristics that are ‘not chosen … are not home’. This choice is especially critical for people with disability, who should be listened to and treated with respect and have a say in where they live (including who they live with) and their key support workers (Cook & Miller, 2012; Miller et al., 2008). The current case study demonstrates that the choice of where a person lives comprises three principal elements: (1) the built environment (i.e., the house and built setting of the dwelling) (Rapoport, 1985); (2) the home environment (i.e., most of the built environment, including the dwelling, neighbourhood and nearby shops and services, although varying groups of people choose ‘different combinations of elements as their home environments’) (Rapoport, 1985, p. 255); and (3) home (a multi-faceted concept) (see Annison, 2000). Smith (1994, cited in Annison, 2000) argued that a ‘home’ is where a person has control over performing important social and personal behaviours. Smith identified essential indicators for a sense of home: positive social relationships, a positive atmosphere engendering warm feelings, care and cosiness, personal privacy and freedom, opportunities for self-expression and development, and a sense of security and continuity (cited in Annison, 2000, p. 258). O’Brien (1994, cited in Annison, 2000) defined three essential elements of ‘home’ for people with intellectual disability in a residential service setting: a sense of place, control over the home and supports for living there, and security of place through tenancy or ownership, including pride of ownership.

The participatory design activities began with the families identifying three broad goals to meet their housing aspirations for the residents’ social inclusion (which the three principal elements would accommodate) (see Fig. 1). First, housing in the community would replace the family home. Second, care and paid support would replace the parents’ roles as caregivers for residents who could not live alone. Third, the residents would remain connected with their social networks and familiar local communities. In the families’ opinion, housing, good quality paid support and community were interdependent objectives. However, their initial ideas regarding care and support were nebulous (RP Rollo) because individual funding was not generally available in 2004.

Individual choice was the primary philosophy guiding the actions and decisions of the participating families and RASAID. The families intended that the residents could choose to live with a community of adults they knew and who were members of RASAID because they lived in or close to Ryde. Specifically, they wanted to enable the residents to live in a community within the community (RP Rollo). Parents worked with the residents so they/their representatives could choose who would live as neighbours or housemates in the cluster. At that stage, one young man with high support needs, who was expected to share a house with four other adults, chose to live alone in his own home in the cluster (RP Shields).

The families, including eight residents, shared their visions of the future homes using a person-centred planning tool, Planning Alternative Tomorrows with Hope (PATH) (Pearpoint et al., 2010; Wood et al., 2019), with trained external facilitators engaged by NSW Ageing, Disability, and Home Care (ADHC), which oversaw the group home system at the time. The RASAID PATH plan (J. Rollo, personal communication, 31 July 2022) identified several goals for the new homes, including houses located together, proximity to families, individual funding for paid support for each resident and acceptance of RASAID’s model for a community within the community (i.e., an intentional community). The goal-specific objectives and who would help achieve them were documented in the PATH plan. Individual plans were also prepared with each resident/family member based on their intimate knowledge of the adult’s needs and interactions with others (RP Rollo).

RASAID’s concept of a cluster-designed housing model is consistent with early urban planning research in the United States. Whyte (1964) studied the ‘cluster’ as the grouping of houses for conservation purposes and using saved land for a common open space or other shared purposes. A thoughtful design for the layout of houses, sufficient open spaces and an attractive garden tailored to the site and its residents is important – the aesthetic appearance of clustered houses must not be neglected (Whyte, 1968). Whyte (1964) noted that ‘cluster’ is not a frozen format, and other connotations of cluster developments include ‘density zoning, planned unit development, and environmental planning’ (p. 12). In the current case study, the cluster model was chosen to help the residents maintain their existing social connections and gain support from their community by locating the individual homes together. However, it was also important to ensure that the design included adequate and appropriate private and shared spaces and an underlying unity regarding roof lines (including a consistent roof line for skylights) and setbacks, which was aesthetically pleasing.

Three research questions (RQ) were addressed in this study: What type of home did parents choose for their children with intellectual disabilities and why? What type of home did they achieve? How did they overcome challenges to accomplish building the home?

2 Theoretical background

2.1 Housing

Housing research in Australia has focused on affordability, need and undersupply of low-rent stock, which includes two social housing types: public and community (Bostock et al., 2004). Although many people with disability live in social housing, they are considered just one among many disadvantaged groups needing government-funded homes (Department of Family & Community Services, 2012) because they cannot afford to rent or buy a house. Historically, people with certain disabilities have been excluded from both social housing types in NSW for various reasons. For instance, public housing includes aged buildings that are inaccessible for some people with physical disabilities (Clark, 2022), while social housing is not rent-free for support workers who need their own room in the person’s home (in contrast with rent exemptions for some carers in the Australian Capital Territory). Adults with disability living with family members have been considered ‘a low priority in housing allocations’ (Wiesel et al., 2015, pp. 2, 54–55) because they were not considered homeless or at risk of homelessness.

2.2 Group homes

In NSW, group homes have been the dominant model for supported residential accommodation (Bigby & Bould, 2017). Although the model was used earlier, Richmond (1983) recommended that people with ‘developmental disability’ moving from institutions be ‘rehoused’ in normal houses in the community. At that time, ‘normal houses’ comprised three- to five-bedroom households on single urban lots that a type of family had aspired to live in since the 1950s (Maginn & Anacker, 2022). More recently, Bigby and Bould (2017) described group homes as ‘average-looking’ houses in ‘ordinary’ streets. In other words, the design format of the house and built setting for group homes has been relatively static in NSW. Regarding the home environment, Richmond (1983) assumed that group home residents would connect with their neighbours and participate in community life. However, no evidence exists that this generally occurred (Cummins & Lau, 2003). Group home living is also inconsistent with the trend towards communal living and co-living environments, where people choose their community and which reflects ‘the wider pattern of Australian households adapting to population growth, housing affordability, and changing lifestyles’ (Gibson, as cited in Plockova, 2021, p. 224). Thus, a community is no longer something out there where people must be placed.

2.3 Residential institutions

In Australia, state or territory governments provided or funded non-profit organisations to operate group homes and support as a bundled service for people with disability, with an increasing number of group homes when large residential institutions were closing down. Early research on this deinstitutionalisation of group living documented the negative aspects of large residential institutions for people with intellectual disabilities (Kugel & Wolfensberger, 1969; Wolfensberger, 1983) and critically examined community life for people with intellectual disabilities living in dispersed living arrangements like group homes (Emerson, 2004; Landesman, 1988). The literature has established that ‘institution’ in a residential setting is a composite concept with various characteristics regarding the built form, staffing model, purpose or function and experiences of people living in such places, which was usually negative (Kugel, 1969; Landesman, 1988; Wolfensberger, 1983). Institution-like features ranged from ‘obsolete architecture and design’ (Kugel, 1969, p. 4), lack of facilities and comfort, segregation, regimented living arrangements and daily activities, and the mistreatment of residents (Landesman, 1988). Other negative aspects included their location in ‘out of the way’ communities, creating issues with recruiting and retaining qualified staff (Kugel, 1969, p. 2). At the same time, Wolfensberger (1983) developed the social role valorisation framework and translated it into goals and processes for delivering services to people with disabilities who have autonomy, rights, individual choice and valued social roles.

More recently, researchers have asked why services in some group homes are often ‘not as good as they should be’ and whether this is due to the operating pressures of the economy, management and regulations on service providers or other factors (Mansell, cited in Clement and Bigby, 2010, pp. 11–12). However, alongside these factors, governments established group homes as segregated accommodations into which people who did not know each other and did not choose to live together were placed as housemates. Segregated accommodation has long been considered a type of institutional living in Australia (Sach and Associates et al., 1991). Additionally, being placed in any home is inconsistent with the person with disability’s right to choose where (and with whom) they live (UN Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, art. 19) (United Nations, 2006).

2.4 Clustered housing versus group homes

By comparing the quality of support services, ratio of support workers to residents, support costs, and mixed quantitative and qualitative measures across the different quality of life (QOL) domains in both cluster housing and dispersed living arrangements (particularly group homes), Mansell and Beadle-Brown (2009) concluded that people with disability experienced better QOL outcomes in group homes with the exception of village (intentional) communities. However, examinations of settings with institution-like characteristics (e.g., large size) as a cluster have been common. For example, Mansell and Beadle-Brown (2009) reviewed 19 studies on the experiences of approximately 2500 people from four countries. ‘Clustered housing’ included ‘clustered settings with at least 100 places’, ‘clustered settings with 20–55 places’, residential campuses providing day services onsite (indicating some residents may not leave the campus) and smaller living arrangements (2009, p. 317). In contrast with these large clustered settings as a service and staffing model, Mansell and Beadle-Brown (2009) acknowledged that village communities (where family members may also live) facilitated close personal relationships and were superior to dispersed living models like group homes.

Conversely, Bigby (2004) criticised intentional communities in a cluster setting for people with intellectual disabilities as institution-like and highlighted Emerson’s (2004) findings of poorer quality care and QOL outcomes for residents with intellectual disabilities in clustered housing in England (leading more sedentary lives, participating in fewer leisure, social and friendship activities, and receiving less support from staff). However, Emerson noted that his findings might not fully represent adults receiving residential support in England – some were used for short-term care – and his research lacked within-study reliability or data collection validity. Indeed, the clustered housing Emerson examined did not exhibit the characteristics of ‘village’ intentional communities, and his views that public agencies cannot provide cluster housing that shares the benefits of ‘village’ (intentional) communities or a ‘connected community of people with intellectual disabilities’ (p. 195) are inconsistent with modern intentional communities. For example, the Rougemont Co-Operative is a governmentfunded, 105-unit housing co-operative in Ontario established for a small number of adults with different disabilities living with many other residents (Deoheako Support Network, n.d.). The Benambra Intentional Community in Canberra was established with government-funded public housing and paid support for three men living separately with their co-residents and neighbours who applied to live there (Hartley Lifecare, n.d.). Additionally, the literature review revealed a lack of longitudinal studies regarding QOL outcomes in both group homes and cluster housing (Mansell & BeadleBrown, 2009) – while the findings pertain to housing models and organisations that have subsequently evolved.

2.5 Building rules and design standards

The challenge of not rebuilding institutions when housing and support are established for people with intellectual disabilities is always present (Landesman, 1988; Mansell & Ericsson, 1996; Sarason, 1969). In the researcher’s opinion, there are additional challenges with building new government-funded housing, where many stakeholders with different priorities and interests must deliver the housing as a property development project. Building professionals (i.e., architects, builders, certifiers and accredited assessors) focus on ensuring designs and final-as-built housing comply with standards and rules, including technical standards and building contracts. Investors or housing providers who own/manage housing assets focus on qualifying for government funding, the quality of building work and maintenance for houses. Policymakers and government agencies monitor compliance with rules and administer housing under government policies.

However, these stakeholders are not responsible for ensuring holistic housing designs or that home environments will meet future residents’ needs and preferences. They may believe that a standard design that can be replicated on a large scale is less costly. Therefore, it is important for people with disability, their representatives and advocates to lay the groundwork for their inclusion in the design process of their housing. Building rules in Australia are based on the function or purpose of a particular type of building, the number and characteristics of people who will occupy that building, the responsibilities of building professionals to achieve safety and quality standards, and planning standards designed to mitigate the negative effects of the design or use of that building on its residents, neighbours and nearby buildings (see Australian Building Codes Board, 2022). Governments also encourage innovation in housing, but building rules, design standards and policies regarding the choice of housemate or co-living must not limit innovation. Sections 2.5.1 to 2.5.3 explain the relevant design standards.

2.5.1 Specialist disability accommodation

Australia’s NDIS commenced in 2013 to replace disability services provided by each state and territory government for people with permanent and significant disabilities (Madden et al., 2013). In 2015, all Australian governments agreed to the NDIS specialist disability accommodation (SDA) pricing and payments framework, developed to determine funding for SDA (KPMG, 2018). Individual funding has been available for people with an ‘extreme functional impairment’ or ‘very high support needs’ (National Disability Insurance Scheme (Specialist Disability Accommodation) Rules 2020 [SDA Rules], s. 11) since 2017; however, other eligibility criteria apply (SDA Rules, s. 14). When a person is deemed eligible for SDA funding (SDA participant) the funding is included in their NDIS-funded plan. Once the SDA participant resides in the SDA and has a service agreement with the provider, the National Disability Insurance Agency (which administers the NDIS) pays that funding to the provider, typically monthly (S. Anthony, personal communication, 28 May 2023). The SDA participant pays a ‘reasonable rent contribution’ (set by the National Disability Insurance Agency) to the provider: currently, 25% of their Disability Support Pension and any Rent Assistance from the Australian Government (SDA Rules, s. 21).

Funding cannot be used for SDAs that ‘are still under development or in planning’ (KPMG, 2018, p. 11). The NDIS Specialist Disability Accommodation Design Standard (SDA Design Standard) lists requirements that must be incorporated into new buildings before they are eligible for enrolment (NDIS, 2019b). When housing meets the enrolment requirements, it is enrolled and becomes eligible for an SDA participant subject to other criteria like the SDA participant’s preferences and support needs (SDA Rules, ss. 16, 24). The SDA Design Standard was not developed when the cluster houses were designed or built. Instead, the government construction contract required the houses to comply with the Livable Housing Design Guidelines (LHD Guidelines) for ageing in place (RP interviews, hereafter, ‘RPs’).

2.5.2 Livable Housing Design Guidelines

The LHD Guidelines (Livable Housing Australia [LHA], 2013, 2017) were developed to ensure new houses are built with design features that support ageing in place. Compliance can be a term of governmentfunded building contracts for constructing disability accommodation or other social housing. In the current case study, the building contract specified that the houses would comply with the LHD Guidelines (LHA, 2013). A more recent version (LHA, 2017) contains 15 livable housing design elements regarding different specification levels for accessible housing. There are seven core elements for achieving a silver-level specification for minimum accessibility (key structural and spatial characteristics, e.g., the path of travel from the street, groundfloor toilet and hobless shower). Additional design elements must be satisfied to achieve a gold-level specification for enhanced accessibility or a platinum-level specification for full accessibility features of all 15 design elements.

2.5.3 Specialist Disability Accommodation Design Standard

The SDA Design Standard (NDIS, 2019b) specifies the minimum requirements for housing in four design categories – improved livability, robustness, full accessibility and high physical support – to ensure SDAs are built to meet a person’s specific disability needs (physical or cognitive). For example, SDA designs for residents who need high physical support must provide power and an inbuilt structure for a ceiling hoist (NDIS, 2019b). Although the SDA Design Standard reduces or removes some design choices of the SDA participant, the NDIS provides new opportunities to consider the role of people with disability as designers of their own homes.

Supported independent living (SIL) funding for an individual’s in-home support is separate from SDA funding (NDIS, 2022). A person eligible for SIL may have more choice over where they live, including public housing and non-SDA community housing, but will require separate SDA funding to live in SDA (including old group homes if enrolled) (SDA Rules, s. 24). Further, some SDA participants will not qualify for SIL depending on their circumstances.

2.6 Participatory design: conflict and contradictions

Even when a participatory design approach is adopted to build new SDAs, and people with disability or their representatives contribute as designers, conflicts and contradictions in these development projects may arise when architects, planning authorities (e.g., local councils), certifiers and builders perform their designated roles to comply with building rules and design standards. These experts’ practices reflect the ‘expert mindset’ of professionals with agreed roles in design and construction processes. Sanders (2008, p. 14) distinguished this ‘expert mindset’ from a ‘participatory mindset’, which includes people with lived experiences across different domains (e.g., disability) in the design process as true design experts. Burkett (2012, p. 2) reported a third ‘user-led’ participatory design approach where people design and create solutions ‘to their own situations’, like the independent living movement of people with disabilities who work for self-determination, equal opportunities and self-help (Barnes et al., 1999).

Research has identified three principles in Scandinavian participatory design approaches, which focus on self-help. First, designs strive for democratisation, for example, to address the lack of access to decision-making power or facilitate greater influence over resources (Gregory, 2003). This includes advocates taking the lead for change by promoting solutions to their own issues that have been overlooked. It can involve one-off co-design activities or events (e.g., workshops) if decision-making and power are shared and boundaries such as disability do not exclude their contribution. Second, value-oriented designs explicitly embed values ‘in design strategies and choices’, discuss ‘values that are implicit and explicit in imagined futures’, and adopt ‘participatory design methods for critiquing the present and envisioning change’ (Gregory, 2003, p. 65). Individuals with cognitive disabilities sometimes use the person-centred PATH tool to share their vision for their imagined future. This principle should also include designs to achieve value-based social change objectives. Third, the approach requires recognising conflicts and contradictions as design resources. For Gregory (2003, p. 66), ‘conflict’ refers to ‘different perspectives, arguments, heterogeneity, or contradictions’. Evidence of conflicts and contradictions includes delays, a lack of progress and setbacks, unresolved differences, unmet agreements and objectives not being achieved, notwithstanding iterative meetings, workshops or other such efforts. Conflicts and contradictions create design resources when one or more stakeholders introduce new ideas, resources, tools or understanding to achieve their objectives.

Foote et al. (2007, p. 651) used activity theory to explain design as a collective activity with contradictions that may ‘generate new tools and understandings, which can shift existing patterns of control, expertise, and legitimacy’ to provide solutions. For example, a participatory approach with a broader group of design experts, such as people with disability, who possess expertise and legitimacy through their lived experiences, may contribute new dimensions and solutions not previously considered. A participatory approach in building design and construction may also align different stakeholders’ priorities and enable interventions to achieve the desired solution (Gregory, 2003). A participatory approach that includes users as designers from a project’s beginning has been recommended (Chbaly et al., 2021).

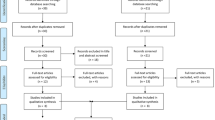

3 Methods

3.1 Case study

A case study was used to report the perspectives of RASAID and the families who challenged the government agencies’ policies, attitudes and practices that failed to provide housing for the residents aged 21 to 50 years in 2004. Their collective advocacy led RASAID to secure government funding to build new houses for the residents. The land was purchased, and building planning commenced in 2013. Construction was completed in 2016. The cluster homes comprise a five-bedroom house, six single-bed units and two two-bedroom villas (see Fig. 2).

3.2 Data collection

Data were collected through semi-structured interviews with three consenting parents. Residents were not interviewed because the study specifically investigated the RASAID families’ system-level activities. Participants were interviewed together on two occasions, each lasting more than one hour. The questions were based on themes drawn from the literature review for the doctoral research. Probing questions helped gain a deeper understanding of the families’ experiences, strategies and activities, including their interactions with other stakeholders to achieve their goals. The University of Technology Sydney Human Research Ethics Committee approved the research and interview questions. Participants consented to the use of their real names in the study.

The disability types of some residents included Cornelia de Lange syndrome, severe to moderate intellectual disability, autistic-like behaviours and anxiety. Verbal skills included limited and mostly non-verbal for a few residents. Some residents could read, and some were quite vocal. Although the researcher visited the cluster twice and met some residents, she was unknown to them, and their activities were not the study’s focus.

Constance, who assisted the parents as the Minister for Disability Services, could not participate after the ethics consent form was sent to him at his request. Prior consent to interview ADHC staff could not be obtained because the ADHC ceased operating after the NDIS commenced and NSW group homes had been outsourced by lease or sale. The community housing provider’s (CHP) project managers and relevant staff had also left their employer before this study.

Historical data analysis included public documents, media releases, newspaper articles and the RASAID PATH plan. Some data were available on RASAID’s (n.d.-a) website, including a draft architectural drawing for the cluster concept. One participant checked RASAID’s diaries to count the meetings with stakeholders for different purposes over 12 years. John Alexander’s (Parliament of Australia, 2017) speech, which is publicly available, also provided a relevant perspective (see Sect. 4.3.3). A separate group of families who incorporated to advocate and establish independent living arrangements for their children were a second case study for the doctoral research. One parent in that study created a record of attractive fixtures/fittings in the RASAID cluster housing and made that record available. In a third case study for the doctoral research, Ms Clark advocated for her daughter’s home. She shared a key document written by RASAID describing its aims for its members.

3.3 Research analysis

NVivo qualitative data analysis software was used for theming the interview and historical data for the doctoral research. Cultural-historical activity theory (Engeström, 2001) was the appropriate framework for mapping thematic data to answer the RQs (see Sect. 1). It provided a structured framework for studying the interaction of six elements of an activity system or unit of activity: (1) the desired goal (object); (2) who desired the goal (subject); (3) who worked with the subject to achieve the goal (network/community); (4) what resources or approaches were used to achieve the goal (tools); (5) how work was shared (division of labour); and (6) what rules (policies, law or norms), attitudes and practices supported or constrained the goal. Figure 3 represents an activity system as an analytical tool with key questions to be answered.

The activity system as an analytical tool (adapted from Leadbetter, 2008, p. 202)

Engeström (2000) demonstrated that activity systems are ‘in constant movement and internally contradictory’ (p. 960), while Foote et al. (2007) noted that contradictions lead to learnings, understandings and tools for new solutions. For example, in the current case study, contradictions existed where the stakeholders’ interests/priorities and objectives were inconsistent or incompatible, tools were inadequate, or rules were barriers for the families to overcome. This was illustrated by the ADHC requiring families to secure construction funding before approving the land and the families acting to secure construction funding from the Australian Government. Social and contextual factors influencing activities (Engeström, 2001; Villeneuve, 2011) are important when parties navigate politics, policies, housing and services over extended periods. Figure 4 illustrates that changes to social and contextual factors over time, like the introduction of the NDIS, can influence prospects of success. Contradictions within the activity systems were analysed and depicted by lightning bolt symbols (Martin, 2008); resolutions of contradictions were depicted by removing the symbols.

The contradictions experienced while developing the cluster housing (adapted from Leadbetter, 2008, p. 202)

Note. RASAID = Ryde Area Supported Accommodation for Intellectually Disabled Inc.

Because the families’ and RASAID’s activities, decisions and transactions occurred over many years, it was necessary to create a timeline of key events to compare the interview data and parents’ activities with publicly available information. This timeline helped identify when progress and setbacks occurred, the relationships between activities or interactions between people/organisations and progress/setbacks, the relationships between particular types of events, resource contributions and the overall process of delivering the cluster model.

3.4 Bias and reflexivity

The researcher’s attitude was reflexive throughout the study because beliefs, biases and values can always be present when conducting interviews (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). Merriam and Tisdell (2016) reminded researchers to consider how their views affect the research process and findings. The researcher for the current case study was a student volunteer in a psychiatric centre for a week in 1976 and observed inappropriate and aggressive behaviour involving vulnerable people. Between 2014 and 2022, she was a volunteer director on the board of three disability service providers and a CHP. She had also worked with politicians and bureaucrats and as a property and finance transaction lawyer. She disclosed her assumption that the families, government and other stakeholders collaborated to build the cluster as a shared objective because of the commitment of government funding and successful cluster construction. She did not disclose her assumption that the Minister for Disability Services would not participate because the study was not governmentfunded or controlled.

4 Results

Three types of government-funded housing systems (public housing, community housing and group homes) were not available for the residents even though some were in their fifties. It was not possible to assume that these housing systems and government agencies that excluded the residents would respond appropriately when parents were too old or sick to provide caregiving or when they died. Therefore, it was a priority for the families to help their children move into their own homes in a planned, timely and orderly way, particularly because some parents were in their eighties. Section 4 addresses the RQs (see Sect. 1) by describing how the families achieved their goal of establishing their child’s own home within their community.

4.1 Research question 1: a cluster-designed home as the goal

The families chose a cluster design for the built and home environment of the new homes to ensure the social inclusion of the residents and meet three broad goals: living in a community within a community, obtaining attractive housing with friendly neighbours and gaining personalised support from support workers chosen by the residents or their representatives following the philosophy of individual choice (RPs). In the PATH plan, the families expressed their vision that the residents would live together as an intentional community of people who are friends or know each other in a location that would help maintain their existing social networks. The families agreed that each resident would live in an aesthetically pleasing house in an attractive street setting with friendly neighbours. People driving or walking past the house should not consider the house or residents any different from themselves.

Regarding paid support, the purpose or function of the clustered homes was not a congregated care/service provider or employment model in which a provider would control both housing and staff allocations (RPs). Similarly, they were not intended to increase the residents’ dependence on paid support. Instead, the families opted for a family-led model with a support provider separate from the housing provider and matched to each resident’s needs. Although the residents or their representatives could terminate the support provider’s services, the families aimed to partner with a provider that shared their person-centred philosophy. While family members living nearby would help when needed, it was intended that they would reduce their oversight as the residents became more confident and vocal in their own homes (RPs).

4.2 Research question 2: person-centred clustered homes as the outcome

4.2.1 Individual choice

The three broad objectives of the cluster housing project (see Sect. 4.1) came to fruition when the residents moved into the completed cluster. First, before their move, the families asked the residents whether they wanted to live alone or with a housemate; the homes reflected their choice or their family representative’s understanding of their preference and interaction with others:

RP Shields: I always thought my son would want to live in the five-bedroom house. I thought he would need that level of support. But one night, we had the plan set up on the kitchen table, and my son said very clearly, ‘I want to be by myself’. So that was the right thing for him.

Second, the families wanted to ensure that the residents would not feel lonely and could live with friends or people they knew as neighbours or housemates in the cluster:

RP Shields: We didn’t know if it was going to be successful. We just thought we were all good friends. The kids didn’t all know each other, but they all knew somebody. There wasn’t anyone going in without any links at all … What we didn’t understand at the time was how well it was going to work.

Third, the families decided that the cluster housing would not appear institution-like. Thus, the families co-designed the private and shared spaces to include the communal room and garden based on their understanding of each resident’s preferences and how they interacted with others.

Fourth, during construction, the families rejected fixtures/fittings that were institution-like, inappropriate or unusable, insisting that such features (added during the building process) be removed:

RP Rollo: It was a deliberate attempt to deinstitutionalise it – make it look like any house in the street. That was our aim, and we actually achieved that. Because you can look around at any houses, and you can pick out the disability houses, but you can’t do that with RASAID.

One example was the wheelchair access stencils for the driveways:

RP Shields: To show them where to park the bus – like it was a council car park or something. But we said ‘no’. And we were able to get the Independent Living Centre [ILC] onsite to tell them this was not needed.

Other examples included installed rails that resembled cattle grids and glass doors in the five-bedroom house that allowed people outside to look in on the residents:

RP Poole: If you have a camber, a ramp of a certain degree, it’s got to have rails under the platinum standards. So, when it was designed, we made sure that all of the paths up to the front doors and everything else was at the right level, so we didn’t have to have railings. We drove past one day, and they’d put all these railings in.

RP Shields: At another stage, they’d put in see-through glass doors for the front doors. We made them take out all the glass doors.

RP Rollo: And all the rails.

RP Poole: They were saying, ‘they had to be in because of this reason’. We said, ‘but that was not in the design’. So, we ended up getting [the ILC] out again. The only way we could get around having the railings [because they had installed the ramps incorrectly] was by not having a gate to every front door, which we didn’t need. So, they had to be filled in.

Fifth, social connections with neighbours and the broader community were extremely important. Therefore, the families invited the community to the sod-turning ceremony to mark the beginning of construction and neighbours to visit the cluster after the houses were built. During their visit, relatives of the previous owner were delighted that a parent had planted the previous owner’s roses back in the garden near the five-bedroom house (RP Rollo).

Sixth, social connection between residents was also critical. Thus, the person-centred design balanced each resident’s need for privacy and control over their private space while ensuring they could visit each other if and when they chose. Generally, the residents eat separately in their homes, but they celebrate birthdays or special occasions in the communal room with its dining area, television, jukebox and barbeque (RPs).

Last, the home environments are person-centred, with the fit-out overseen by parents to the maximum extent possible (RPs). Each bathroom was individualised, and each resident chose their feature tiles and bath or shower with shower screens for privacy. Each resident also chose the colour of the feature walls in their bedrooms. Some parents persisted in having a purpose-built wardrobe, which had to fit all their belongings, including linen. Air conditioners and fans were installed for temperature control. Attractive features, including plantation shutters, were also added. With their attention to aesthetic and functional details, the parents created a home environment that was comfortable, welcoming, attractive and easy to use.

RASAID has continuously operated as a family-led group, overseeing living arrangements, house maintenance and paid support for the residents. In 2014, RASAID appointed a service provider to employ support workers for the residents. The paid support arrangement began in 2016 when the residents moved into their new homes. Years later, family members still visit weekly or more regularly to keep an eye on different issues, including attendance at individual appointments, changes to rostered staff and the safety and happiness of the residents. The parents do not require permission to visit and can freely access their family members’ files, which their support worker maintains.

4.2.2 Participatory design

When the cluster was built, each RP took a slightly different approach to enable the residents to choose to move into their own homes. One RP’s son ‘hates change of any sort’, so he started with a single night as a trial. When his parents asked him about it, he answered, ‘not sure’. He returned to the cluster (‘just overnight’) for a second trial and has not slept at the family home since:

RP1: As soon as he understood this was his place, he said, ‘this is my place’. They say, of all of them, my son is the most proprietorial, and sometimes he’ll tell a staff person, ‘this is my place. I don’t want you’. I think it is good.

Another RP’s son was meant to move into his new home gradually:

RP2: He went for two nights, and he was okay. Now, he’ll only come [back to the family] home for Christmas and Easter.

RP1: And he’s changed a lot. He’s become much more vocal.

RP2: Vocal, outgoing, and again, he will say, ‘I don’t want to do that’. He’s completely changed.

RP1: He’s also taken over the role of tour guide.

The third RP’s son was expected to transition slowly. His mother chose the cluster because she felt he would be safer. It was also important that he have people to interact with because he was used to having many family members around. He visited the cluster when it was being built:

RP3: He knew this was where he was going to live. I was afraid that he wouldn’t transition well. So, I took him there for his first night, thinking he would be back home the second night. He hasn’t been home since because that’s his house.

RP2: Actually, he would not put his shoes on, so he couldn’t get on the bus.

This son’s decision regarding his shoes was his way of communicating his decision to move into his cluster home.

RASAID successfully provided the residents with a sense of place. They were so attached to their personal spaces that, in 2019, they rejected some parents’ suggestion that they move around in the cluster. The parents described this learning:

RP1: They’ve attained ownership of their own little place.

Researcher: Did you envisage that?

RP3: No.

RP1: They couldn’t ever have ownership before.

RP3: It’s a really positive outcome. They’re very house-proud.

For context, the NDIS was being implemented as the residents moved into the cluster housing. Policy changes included individual funding before the NDIS commenced and the classification of the cluster housing as SDA after the pricing and payments framework was implemented (RPs). The residents receive individual SDA funding of approximately AUD30,000 annually; thus, approximately AUD450,000 (15 × AUD30,000) is paid each year to the CHP as an SDA-registered provider. It is expected that the CHP will apply this funding to build more SDAs because the NSW and Australian governments funded the cluster’s construction and land purchase, respectively. The residents also receive SIL funding for paid support workers who assist each resident in their home.

4.3 Research question 3: overcoming challenges to achieve cluster housing

The families overcame numerous challenges to ensure the cluster-designed homes were completed. They began monthly meetings in October 2004. RP Rollo learnt about the importance of registering an organisation as a charity for fundraising when she started a support group for people with her son’s type of disability, their families and carers. Thus, the participatory design activities to deliver the new homes included the incorporation of RASAID by RP Rollo to represent the families as a collective and its registration as a charity to receive donations. The families then developed RASAID’s objectives and strategies to secure government funding for the land, paid support and construction. The doctoral research RPs explained that RASAID’s corporate status distinguished collective activities from individual activities and provided the families with corporate standing to lobby politicians and bureaucrats, which was the first step in the design process.

The families then met with successive ministers for disability services; however, none agreed to fund the project. It was a turning point when Constance became the new Minister for Disability Services (NSW) and committed AUD3 million to purchase land for the development in April 2011 and individual paid support for each resident (RPs). At the same time, political support for a national disability scheme was growing across Australia, including the Productivity Commission’s (2011) recommendation to introduce the NDIS.

Nonetheless, the families encountered new challenges to their participation in design decisions when other stakeholders with conflicting interests (Chbaly et al., 2021) were engaged in delivering the project. In particular, the parents encountered unnecessary bureaucracy and the ADHC’s contention that the houses be built using a standard group home design, which delayed their progress (RPs).

4.3.1 Bureaucracy

First, the NSW Government agreed to fund only the land for the project and required a CHP (selected by the ADHC or the Minister for Disability Services) to own the land and manage the housing to be built for the residents (RPs). The Registrar of Community Housing (n.d.) regulates CHPs in NSW under a registration framework that requires CHPs to report the efficient delivery of new housing for low-income tenants and residents. The CHPs had experience operating social housing; however, they generally had little understanding of disability accommodation or the philosophy of control and choice at this time (i.e., providing residents with intellectual disabilities choice over where and with whom they live and enforceable rights as tenants). The ADHC and CHPs had limited (if any) experience sharing control in designing or constructing a property with future residents, and the families could not control when the funding would be spent or new homes built (RPs).

Second, the Minister for Disability Services handed the cluster project to the ADHC and requested its staff to help the families build new homes. However, the AUD3 million funding was insufficient to both purchase the land and build on it. The ADHC staff insisted that the land could not be purchased until the families provided or secured construction funding (RPs). The parents approached the Australian Government for assistance, and a key politician encouraged them to apply for grant funding from the AUD60 million Supported Accommodation Innovation Fund (SAIF), which was established to help build ‘innovative, community-based accommodation places for people with disability’ (Department of Social Services, 2014, para. 1). When RASAID informed the ADHC that they intended to apply for SAIF funding, the ADHC responded that the SAIF was not for RASAID. The families disagreed and applied for a SAIF grant in partnership with the CHP in November 2011. In April 2012, RASAID and the CHP were awarded a SAIF grant to build RASAID’s cluster design homes (RPs).

Third, the land selection process for the cluster housing was bureaucratic. The location was important because the residents needed to remain close to their work or day programs and reduce the need for long and expensive travel (RASAID, n.d.-b). However, other stakeholders were seeking big blocks of land in industrial and other unsuitable areas. Therefore, the families intervened and found the required land in a friendly neighbourhood with help from Rotary Macquarie Park, which the vendor was willing to sell at ‘mate’s rates’ (RP Rollo). The land was a level block, which was ideal for the residents – unfortunately, unnatural levels were created during the building work (RPs).

4.3.2 Group home model

The families’ next challenge arose when the ADHC staff stated that the new homes should be built using the standard group home design because they did not approve of people with intellectual disability living together in clustered housing. The ADHC staff informed the families that the cluster would rebuild institutions:

RP Rollo: [ADHC staff said] everybody has to have their own gate, their own letterbox, their own parking space … And we said, ‘but none of them drive’ … And they said, ‘well, let’s look at the design’. So, they got this mock design … [and] everybody had a letterbox and front gate and the car space. And there was no yard. The house, what was then a four-bedroom house, had no windows. You had a front door, a back door and no windows.

The families rejected the mock design and were determined that the new homes would be an innovative cluster design. The ADHC and CHP organised a workshop to discuss the ADHC’s design with the families and other stakeholders who were not known to the families. Using butcher paper and other tools, the ADHC staff and the CHP produced 20 concept plans, which the families would not approve. The RASAID parents finally said, ‘no, stop – clear it’ (RP Rollo). Two parents visited the draftsman’s office and, over two hours, explained their aims and finally achieved a basic plan reflecting their concept. They also refused to accept the ADHC’s objection to a communal room in the cluster: ‘That was a big fight’ (RP Poole). Thus, the findings reveal that the design and construction processes involved numerous conflicts, iterative meetings and interventions by the parents because the ADHC staff, CHP, project managers and builder had no understanding or experience with disability, person-centred design or individualised funding.

4.3.3 Building rules and design standards

During construction, two RASAID parents (and RPs) invited themselves to meetings with the builder, CHP and project managers to ensure the collective plan was accomplished. They learnt that the application and interpretation of the LHD Guidelines were problematic.

First, the families were informed that the houses would be built following platinum-level specifications due to government funding, even though silver- or gold-level specifications usually apply (Australian Building Codes Board, 2018). Several aspects of these specifications were unclear at that time, and interpretation of the platinum-level design elements was contested during construction and difficult to apply to housing for people with intellectual disabilities:

RP Poole: The housing provider, and the people overseeing the build, said everything had to be the platinum standard, but everybody’s definition of platinum was different. They said everything had to be wheelchair-accessible, but they were putting in basins too low, toilets too high, and benches were the wrong height …

RP Shields: We weren’t going to have kitchen cupboards because we had to have wheelchair-accessible sinks and things. We said, ‘ … but our guys are not in wheelchairs’.

RP Poole: Two were in wheelchairs.

Researcher: Their idea of disability was physical disability?

RP Poole: Absolutely.

Second, although the parents were design experts in understanding their children’s needs and preferences, they were not well-versed in the applicable building rules or design standards. Therefore, they engaged a building expert from the Independent Living Centre NSW (ILC) who was a wheelchair user:

RP Poole: We got [the expert] from the [ILC] involved. Fantastic man. He was a builder who had an accident, so now he’s in a wheelchair … He came around when we’d started building, and he’d say, ‘the toilet’s too high; I can’t go across onto it’, and ‘the basins are too low’.

The cluster builder listened to and learnt from the ILC builder because he could interpret the building code, technical rules and design guidelines from the perspective of a person with disability while explaining or demonstrating onsite when something did not work. The ILC builder was both a disability and building expert.

While the families had prioritised the design requirements for the home environment and the residents’ functional needs and preferences, the builder’s role was to build the cluster following architectural design and comply with relevant building rules and design standards for asset-based outcomes (RPs). When construction began, the builder and other construction experts were accountable to the ADHC, the CHP, the federal government agency that administered the SAIF grant and their respective project managers. However, none of these experts understood or had experience with the residents’ disabilities. Thus, the families’ design activities during construction involved intervention by two RASAID parents, iterative meetings and some disagreements:

RP Rollo: Although they had our money, we had our collective plan of what we wanted. We knew what individuals needed within that plan. We said, ‘it’s our place, so we’re coming to your meetings’.

From the families’ perspective, they achieved person-centred outcomes using their cluster housing design by focusing on various typologies for the individual houses chosen by the residents, family governance of paid support using RASAID, social relationships for the residents (including how they would experience daily life in their own homes) and ways for giving them control and choice in their home environment. The families agreed on ‘what they wanted as a group and singly’ when asking the residents how they wanted to live (RP Shields), for instance:

RP Shields: We did ask each individual that was going to move in where they wanted to live. We built the place for the people that were going to live there, as they requested it.

Indeed, from Alexander’s perspective (Parliament of Australia, 2017), the state-of-the-art RASAID cluster was accomplished through the parents’ perseverance, tenacity and strength.

5 Discussion

This case study aimed to use three RQs (see Sect. 1) to examine community living and a cluster home model for adults with intellectual disability requiring paid support. The RASAID families chose cluster-designed housing for the residents to live in a community together in an inclusive and friendly neighbourhood close to family and friends (see Sect. 4.1). They achieved person-centred homes that were individualised according to the residents’ requests (see Sect. 4.2). Engeström’s (2000) activity theory framework was used to map family-led system-level activities across different sectors and examine how families achieved their goals. The relevant systems were identified by the resources needed to create the new homes and people in positions with authority who could commit those resources, including politicians responsible for government agencies that supplied or operated housing assets or services for people with disability. The resources or tools used to build the families’ participatory approach included housing advocacy; lobbying politicians across different government levels (state and federal); community campaigning, persistence and determination; and incorporating RASAID to represent them when meeting with key stakeholders, including government agency staff, ministers for disability, the CHP, project managers and building professionals (see Sect. 4.3).

A CHP began working with the ADHC and families, learning the design requirements for individualised, person-centred homes, when the Minister for Disability Services required that the homes be owned and operated as community housing assets instead of funding RASAID to build the cluster (RPs). The families had not invited assistance from a CHP because the community housing system had not been available to people with disability who needed paid support in their homes seven days a week. Although the families could not fund the land purchase or construction, they contributed their advocacy, knowledge of their children’s disabilities and understanding of the design requirements for the individual homes, which would be nested within a modern, family-led cluster-designed community. The families included the residents in the design process and empowered them to choose their new homes (see Sect. 4.2). Most importantly, the residents have attained ownership over their homes, pride in where they live and security of tenure (see Sect. 4.2.2).

Family oversight (i.e., family governance) remains in place – the families monitor the quality of paid support, chosen support workers and the CHP’s maintenance of the houses (RPs). To maintain an inclusive, person-centred community of friends or peers, RASAID manages vacancies with a waiting list of people who wish to become residents when the opportunity arises. Some people on the waiting list require either a single unit, the high-care house with five residents or a lower-support house living with another resident. The main criterion is compatibility with the current residents; however, vacancies are rare, with only two in seven years (E. Shields, personal communication, 28 May 2023).

6 Conclusion

The families and RASAID defied the beliefs of the ADHC staff that the residents should not live in a group. They withstood criticism of the cluster housing model from the ADHC, which argued that the cluster would simply recreate institutions. However, this case study has confirmed that housing is institution-like if it creates barriers to the critical elements of community participation, social connection, person-centred support and individual choice regarding private and shared spaces. Conversely, the cluster-designed homes were chosen to access and improve those critical elements.

Indeed, the families argued that if other people could live together in groups, the residents who knew each other should also be permitted to live as neighbours or housemates. Further, the study demonstrated that the smaller five-person group could live in a high-support home not controlled by the support or housing provider. In the cluster, these residents can visit each other if they choose and continue to participate in outside employment or daytime activities. The overriding priority is that negative institution-like practices are challenged and residents’ needs are funded and met. The families demonstrated that the social outcomes for the residents were positive in ways neither residents nor families anticipated. The cluster design – as a built and social format – achieved individual, person-centred homes for residents who were proud to live there, offering a model for existing groups with strong community ties or who choose to live together. The model is for groups of people with intellectual disabilities who receive NDIS-funded SIL and can be replicated.

This case study demonstrated that the social benefits of individual and group living warrant further study. The credibility and transferability of the findings from a single case study with only 15 residents require further research on the cluster-designed model. Future research could also investigate living arrangement models from the social relationship, government and CHP perspectives. Developing this knowledge and using participatory approaches would improve the design of communities and homes in government-funded housing, enabling better social and housing outcomes for residents. Further, researchers should continue exploring the relationship between the design or typology of physical housing (e.g., clustered housing or group homes), individual choice of housing locations and living arrangements, control of paid support, and outcomes (e.g., cost and QOL).

Finally, institutions are not just a form of housing or the number of residents or key workers. Rules regarding how many people can live together must accommodate opportunities for stronger social connections, different community types and choice of location and housemates. Government attempts to innovate and improve housing systems, including access to all housing systems for people with disability, can fail if policies require segregated living or limit group sizes. A Home for Living: Specialist Disability Accommodation Innovation Plan (NDIS, 2019a) anticipated that modern SDA designs would promote independence, community inclusion and government-funded housing that is not population-dense. The families offered such innovation through their alternative housing approach. Notably, NDIS funding was offered and received after the cluster was built, demonstrating that it will fund innovation when governments welcome new ideas and flexible funding rules.

Data Availability

Interview transcript is saved on STASH storage system.

References

Annison, J. E. (2000). Towards a clearer understanding of the meaning of ‘home’. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 25(4), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250020019566-1.

Australian Building Codes Board (2018). Accessible housing options paper September 2018. https://www.abcb.gov.au/resource/report/options-paper-accessible-housing-2018.

Australian Building Codes Board (2022). National Construction Code 2022. https://ncc.abcb.gov.au/.

Barnes, C., Mercer, G., & Shakespeare, T. (1999). Exploring disability: A sociological introduction. Polity Press.

Bigby, C. (2004). But why are these questions being asked? A commentary on Emerson (2004). Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 29(3), 202–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250412331285181.

Bigby, C., & Bould, E. (2017). Guide to good group homes. Evidence about what makes the most difference to the quality of group homes. Centre for Applied Disability Research. https://doi.org/10.26181/22240195.v1.

Bostock, L., Gleeson, B., McPherson, A., & Pang, L. (2004). Contested housing landscapes? Social inclusion, deinstitutionalisation and housing policy in Australia. Australian Journal of Social Issues, 39(1), 41–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1839-4655.2004.tb01162.x.

Burkett, I. (2012, July 13). Co-designing for social good part 1: The role of citizens in designing and delivering social services. Pro Bono Australia. https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2012/07/co-designing-for-social-good-part-i-the-role-of-citizens-in-designing-and-delivering-social-service/.

Chbaly, H., Forgues, D., & Ben Rajeb, S. (2021). Towards a framework for promoting communication during project definition. Sustainability, 13(17), https://doi.org/10.3390/su13179861. Article 9861.

Clark, M. (2022, October 1). A public housing tenant passed away in his home. It took authorities 12 days to find him. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-10-01/why-tenants-northcott-public-housing-estate-feel-left-behind/101484922?utm_source=sfmc&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=abc_news_newsmail_am_sfmc&utm_term=&utm_id=1950786&sfmc_id=352211063.

Clement, T., & Bigby, C. (2010). Group homes for people with intellectual disabilities: Encouraging inclusion and participation. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

Cook, A., & Miller, E. (2012). Talking points: Personal outcomes approach – practical guide. Joint Improvement Team. https://lx.iriss.org.uk/content/talking-points-personal-outcomes-approach-practical-guide.html.

Cummins, R. A., & Lau, A. L. D. (2003). Community integration or community exposure? A review and discussion in relation to people with an intellectual disability. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 16(2), 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1468-3148.2003.00157.x.

Deoheako Support Network. (n.d.). Our history. https://www.deohaeko.ca/our-history/.

Department of Family & Community Services (2012, October). Going home staying home reforms: Consultation report. https://apo.org.au/node/32063.

Department of Social Services (2014, November 7). Supported accommodation innovation fund (SAIF). https://www.dss.gov.au/our-responsibilities/disability-and-carers/program-services/for-service-providers/supported-accommodation-innovation-fund-saif.

Earl, D. (2007). Caring for the children. Forever: Parent-run organisations for children with disabilities in New South Wales, 1950–1968 [Bachelor thesis, The University of Sydney]. Find & Connect. https://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/nsw/bib/NP0000903.htm.

Emerson, E. (2004). Cluster housing for adults with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 29(3), 187–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250412331285208.

Engeström, Y. (2000). Activity theory as a framework for analyzing and redesigning work. Ergonomics, 43(7), 960–974. https://doi.org/10.1080/001401300409143.

Engeström, Y. (2001). Expansive learning at work: Toward an activity theoretical reconceptualization. Journal of Education and Work, 14(1), 133–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080020028747.

Foote, J. L., Gregor, J. E., Hepi, M. C., Baker, V. E., Houston, D. J., & Midgley, G. (2007). Systemic problem structuring applied to community involvement in water conservation. Journal of the Operational Research Society, 58(5), 645–654. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jors.2602248.

Gregory, J. (2003). Scandinavian approaches to participatory design. International Journal of Engineering Education, 19(1), 62–74. https://www.ijee.ie/contents/c190103.html.

Hartley Lifecare. (n.d.). Benambra Intentional Community. https://www.hartley.org.au/event/benambra-intentional-community/home.

KPMG (2018, December 3). Specialist disability accommodation pricing and payments framework review: Final report. https://www.dss.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/02_2019/sda-framework-review-08022019.pdf.

Kugel, R. B. (1969). Why innovative action? In R. B. Kugel & W. Wolfensberger (Eds.), Changing patterns in residential services for the mentally retarded (pp. 1–14). President’s Committee on Mental Retardation. https://mn.gov/mnddc/parallels2/pdf/60s/69/69-CPS-PCR_TOC_Chapter_1.pdf.

Kugel, R. B., & Wolfensberger, W. (Eds.). (1969). Changing patterns in residential services for the mentally retarded. President’s Committee on Mental Retardation. https://mn.gov/mnddc/parallels2/pdf/60s/69/69-CPS-PCR_TOC_Chapter_1.pdf.

Landesman, S. (1988). Preventing ‘institutionalisation’ in the community. In M. P. Janicki, M.W. Krauss, & M. M. Seltzer (Eds.), Community residences for persons with developmental disabilities: Here to stay (pp. 105–106). P. H. Brookes Publishing.

Leadbetter, J. (2008). Learning in and for interagency working: Making links between practice development and structured reflection. Learning in Health and Social Care, 7(4), 198–208. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-6861.2008.00198.x.

Livable Housing Australia (2013). Livable housing design guidelines (3rd ed). https://apps.planningportal.nsw.gov.au/prweb/PRRestService/DocMgmt/v1/PublicDocuments/DATA-WORKATTACH-FILE%20PEC-DPE-EP-WORK%20PP-2021-858!20210130T010232.523%20GMT.

Livable Housing Australia (2017). Livable housing design guidelines (4th ed.). https://livablehousingaustralia.org.au/downloads/.

Madden, B., McIlwraith, J., & Brell, R. (2013). The National Disability Insurance Scheme handbook. LexisNexis Butterworths.

Maginn, P. J., & Anacker, K. B. (2022). Suburbia in the 21st Century: From dreamscape to nightmare? Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315644165.

Mansell, J., & Beadle-Brown, J. (2009). Dispersed or clustered housing for adults with intellectual disability: A systematic review. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 34(4), 313–323. https://doi.org/10.3109/13668250903310701.

Mansell, J., & Ericsson, K. (1996). Conclusion: Integrating diverse experience. In J. Mansell, & K. Ericsson (Eds.), Deinstitutionalization and community living: Intellectual disability services in Britain, Scandinavia and the USA (pp. 241–253). Chapman & Hall.

Martin, D. (2008). A new paradigm to inform inter-professional learning for integrating speech and language provision into secondary schools: A socio-cultural activity theory approach. Child Language Teaching and Therapy, 24(2), 173–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265659008090293.

Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation (4th ed.). Jossey-Bass.

Miller, E., Cooper, S. A., Cook, A., & Petch, A. (2008). Outcomes important to people with intellectual disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 5(3), 150–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-1130.2008.00167.x.

National Disability Insurance Scheme (2019a). A home for living: Specialist disability accommodation innovation plan. https://www.humehousing.com.au/documents/PB_SDA_Innovation_Plan_2019_PDF.pdf.

National Disability Insurance Scheme (2019b, October 25). NDIS specialist disability accommodation design standard (Edition 1.1). https://www.ndis.gov.au/providers/housing-and-living-supports-and-services/specialist-disability-accommodation/sda-design-standard.

National Disability Insurance Scheme (2022). Home and living supports. https://ourguidelines.ndis.gov.au/supports-you-can-access-menu/home-and-living-supports.

National Disability Insurance Scheme Act 2013 (Cth).

National Disability Insurance Scheme (specialist disability accommodation) rules 2020 (Cth).

NSW Government (2006). Accommodation and support paper.

Parliament of Australia. Parliamentary debates: Ryde area supported accommodation for intellectually disabled. House of Representatives. 31 May 2017, p. 5887 (John Gilbert Alexander). https://parlinfo.aph.gov.au/parlInfo/search/display/display.w3p;query=Id:%22chamber/hansardr/d9d65fb0-9d7e-46cb-902a-2cfd08f895ba/0161%22;src1=sm1.

Pearpoint, J., O’Brien, J., & Forest, M. (2010). PATH: A workbook for planning possible positive futures. Inclusion Press.

Plockova, J. (Ed.). (2021). Come together: The architecture of multigenerational living. Gestalten.

Productivity Commission (2011). Disability care and support (Report No. 54, 31 July). https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/disability-support/report.

Rapoport, A. (1985). Thinking about home environments: A conceptual framework. In I. Altman, & C. M. Werner (Eds.), Home environments (pp. 255–286). Springer.

Registrar of Community Housing. (n.d.). About us. https://www.rch.nsw.gov.au/about-us.

Richmond, D. T. (1983). Inquiry into health services for the psychiatrically ill and developmentally disabled. Division of Planning and Research, Department of Health, NSW. https://www.nswmentalhealthcommission.com.au/content/richmond-report.

Ryde Area Supported Accommodation for Intellectually Disabled Inc. (n.d.-a). Home. https://www.rasaid.org.au/.

Ryde Area Supported Accommodation for Intellectually Disabled Inc. (n.d.-b). Introduction to RASAID, vision and model.

Sach and Associates, Miller, T., & Burke, T. (1991). The housing needs of people with disabilities. National Housing Strategy discussion paper. Australian Government Publishing Service.

Sanders, L. (2008). On modeling: An evolving map of design practice and design research. Interactions, 15(6), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1145/1409040.1409043.

Sarason, S. B. (1969). The creation of settings. In R. B. Kugel & W. Wolfensberger (Eds.), Changing patterns in residential services for the mentally retarded (pp. 341–358). President’s Committee on Mental Retardation. https://mn.gov/mnddc/parallels2/pdf/60s/69/69-CPS-PCR_TOC_Chapter_1.pdf.

Stubbs, M., Webster, A., & Williams, J. (2020, October 8). Persons with disability and the Australian Constitution. Royal Commission into Violence, Abuse, Neglect and Exploitation of People with Disability. https://apo.org.au/node/308794.

United Nations. (2006). Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. https://social.desa.un.org/issues/disability/crpd/convention-on-the-rights-of-persons-with-disabilities-crpd

Villeneuve, M. (2011). Learning together: Applying socio-cultural activity theory to collaborative consultation in school-based occupational therapy [PhD thesis, Queen’s University]. QSpace. http://hdl.handle.net/1974/6787.

Whyte, W. H. (1964). Cluster development. American Conservation Association.

Whyte, W. H. (1968). The last landscape. University of Pennsylvania Press.

Wiesel, I., Laragy, C., Gendera, S., Fisher, K., Jenkinson, S., Hill, T., Finch, K., Shaw, W., & Bridge, C. (2015). Moving to my home: Housing aspirations, transitions and outcomes of people with disability (Final Report No. 246). Australian Housing and Urban Research Institute. https://www.ahuri.edu.au/research/final-reports/246.

Wolfensberger, W. (1983). Social role valorization: A proposed new term for the principle of normalization. Mental Retardation, 21(6), 234–239. https://doi.org/10.1352/1934-9556-49.6.435.

Wood, H., O’Farrell, K., Bjerk-Andersen, C., Mullen, C., & Kovshoff, H. (2019). The impact of planning alternative tomorrows with Hope (PATH) for children and young people. Educational Psychology in Practice, 35(3), 326–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2019.1604323.

Acknowledgements

No previous publications.

Funding

Funding has not been received for the case study research or paper.

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Disclosure statement

No financial interest or benefit has arisen from the direct application of the research.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bailey, S.M., Christensen, P., Sankaran, S. et al. Building person-centred homes: a case study of a cluster-designed home for adults with intellectual disability in Australia. J Hous and the Built Environ 39, 345–369 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-023-10050-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-023-10050-0