Abstract

In recent years, an emerging strand of research has focused on the role arrival neighbourhoods play for newcomers finding their footing in a new urban context. However, little is known about the underlying factors and drivers influencing their function(ing). This concerns in particular the role of the local housing market and its players in shaping their emergence and development. The paper deals with the question of how arrival neighbourhoods are (co-)produced by housing market players and how the latter are embedded in local governance structures. Looking at three German arrival neighbourhoods, the article illustrates how they are co-produced by ownership structures and the allocation practices of different housing market players. However, the strengthening of an arrival neighbourhood´s function not only depends on ownership structures but also on the capacities of municipal housing providers and civil society organisations, their strategic goals and the will for (concerted) action. Our findings show that arrival neighbourhoods can take on an important citywide function, enabling newcomers to gain a foothold in the city if three criteria are met: they are accessible/affordable for low-income groups, are equipped with infrastructures for newcomers, and are permeable with regard to residents’ relocation to other neighbourhoods.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

The influx of refugees in recent years illustrates the important role played by arrival neighbourhoods for newcomers finding their footing in a new urban context. Empirical research highlights the overlapping of old and new migration and new (super)diversities in these neighbourhoods (Haase et al., 2020; Hanhörster & Wessendorf, 2020; Vertovec, 2007, 2015; Wiest, 2020). Alongside a high concentration of people with a migration background,Footnote 1 ongoing in-migration from abroad and high fluctuation rates, arrival neighbourhoods are characterised by (compared to the city as a whole) more affordable rents and/or accessible local housing market segments for migrant newcomers (Saunders, 2010; Schillebeeckx et al., 2018).

While there is a growing body of literature on the positive but also detrimental effects that living in these neighbourhoods can have on the arrival of migrant newcomers (El-Kayed et al., 2020; Hans & Hanhörster, 2020), the underlying factors and drivers influencing the function and dynamics of these neighbourhoods remain under-addressed. This finding concerns in particular the role of the housing market and its players in shaping the emergence and development of arrival neighbourhoods. Housing has an important function not only in the process of migrant newcomers’ arriving, but also in their moving on (Ager & Strang, 2008; Grzymala-Kazlowska & Phillimore, 2017). The structure of the (regional) housing market influences people’s distribution in the urban space. People with fewer resources, often including those with a migration background, are particularly affected by the limited availability of affordable housing. Furthermore, they regularly face discrimination through housing providers’ selective allocation policies (Arbaci, 2007; Fonseca et al., 2010). The results are a generally poorer supply of housing and a spatial concentration of people with a migration background in deprived (arrival) neighbourhoods (Dill & Jirjhan, 2014) where several low-income social groups compete for (the few) affordable housing units.

Using three German case studies as its basis, this article illustrates that the ownership structures and allocation practices of different institutional housing providers significantly influence the production and possible dynamics of arrival neighbourhoods, regarding for example accessibility or permeability of the housing stock. Furthermore, their involvement in local networks (together with city administrations and civil society) and the prevalent national ‘social mix’ and ‘social stability’ planning paradigms influence migrants’ access to the housing market.

Thus, we understand housing players’ practices and governance arrangements as an active ‘doing’ of migration (Amelina, 2017), leading to a co-production of arrival neighbourhoods. Despite their important role in shaping migrants’ access to the housing market, we currently know little about the strategies of housing companies, city administrations and civil society in dealing with arrival neighbourhoods and their involvement in the production of arrival neighbourhoods. Given these research gaps, the following question and sub-questions guide our research:

How are arrival neighbourhoods (co-)produced by different housing market stakeholders?

-

What functions are assigned to arrival neighbourhoods by different housing market stakeholders?

-

Which specific strategies do different players pursue regarding the housing market in arrival neighbourhoods and how do these strategies affect the production of arrival neighbourhoods?

-

What role do local governance arrangements play in the co-production of arrival neighbourhoods?

The analysis is based on a comparative study of arrival neighbourhoods and the respective housing market dynamics in the German cities of Dortmund, Hanover and Leipzig. In order to answer the above questions, expert interviews were conducted with various housing providers. Local documents and statistics were also evaluated.

In the following section, current key research strands on the nexus of arrival neighbourhoods and the housing market (2.1) and migrants’ access to the German housing market (2.2) are discussed. Section 3 presents the selected case studies and the research design. The cross-case study analysis in sect. 4 is structured according to different housing market stakeholders’ positions and strategies in co-producing arrival neighbourhoods (4.1 to 4.3). This is followed by a discussion of key findings in sect. 5 and the concluding sect. 6.

2 Arrival neighbourhoods and the housing market

Dynamics in arrival neighbourhoods are closely interlinked with the housing market. Information on the German housing market and the German ‘social mix’ planning paradigm thus sets the context for a better understanding of housing market accessibility for migrant newcomers.

2.1 The nexus of arrival neighbourhoods and the housing market

Research on neighbourhoods shaped by immigration has a long tradition, beginning with the Chicago School’s model of invasion and succession and their famous concept of ‘zones in transition’ (Park, 1915). In recent years, driven by the influx of refugees as of 2014, an emerging strand of research has focused on new features of migrant newcomers’ arrivals in European cities. Research refers here mostly either to the macro-level of state policies or to newcomers’ micro-level agency. One important macro-level process is the financialisation of the housing market. Research illustrates how return-on-investment (ROI) expectations are rising and how permanent price pressure is being exerted on rents and real estate, leading to higher social segregation rates in several European countries (Aalbers, 2016; Fields & Uffer, 2016; Wijburg et al., 2018). Many micro-level studies focus on how newcomers navigate the system in their attempts to access the housing market, and on their emerging (transnational) networks (Kohlbacher, 2020; Wessendorf, 2018). However, what are lacking most are meso-level studies focusing on factors such as local housing supply and governance arrangements shaping opportunity (or constraint) structures on the housing market and in turn co-producing arrival neighbourhoods. This is the field our study wants to contribute to.

What complicates both academic and local planning debates is the lack of a common understanding of arrival neighbourhoods in research, policymaking and planning. In the following, we define arrival neighbourhoods as urban neighbourhoods characterised by a high concentration of migrants, sustained international in-migration and high fluctuation rates. In a citywide comparison, it is easier to find affordable rental housing in these neighbourhoods due to its higher supply (El-Kayed et al., 2020; Haase et al., 2020; Kohlbacher, 2020; Kreichauf et al., 2020). Like most research on arrival neighbourhoods, our paper focuses on those neighbourhoods not only characterised by migration but also by a concentration of income poverty.

In some arrival neighbourhoods, in-migration has been happening for decades. These areas are therefore characterised by a heterogeneity of people with a ‘migration background’ and of living situations ranging from ‘established’ second-generation migrants (partly tenants, partly homeowners) to refugees and other migrant newcomers in precarious situations. Informal brokering by individuals (e.g., established migrants living in the area) facilitates a concentration of newcomers, thus contributing to the (re)production of arrival neighbourhoods (Meeus et al., 2018; Wessendorf, 2018). However, the flip side of informal structures in some arrival neighbourhoods is a growing secondary housing market where newcomers are channelled into mostly overpriced, run-down housing (mostly in the hands of private owners), as illustrated by Schillebeeckx et al., (2018: p 144) using the example of Antwerp-Noord. Thus, both formal and informal processes and their interplay contribute to the production of arrival neighbourhoods (Bernt et al., 2022).

Importantly, the term 'arrival neighbourhood' captures a wide spectrum of city neighbourhoods. For example, their location and characteristics within a city differ depending on the respective housing market and migration history. While in less tight housing markets arrival neighbourhoods are found in inner-city locations with a mixed housing stock, in tighter ones an increasing concentration of new immigrants can also be observed in the urban periphery (El-Kayed et al., 2020). Some arrival neighbourhoods (especially those in inner cities) have a long tradition of welcoming migrant newcomers, while others have experienced a completely new momentum through the influx of refugees in recent years (Gerten et al., 2022). These new arrival neighbourhoods often develop in areas unattractive for other city dwellers. Characterised by high vacancy rates associated with redevelopment backlogs and a concentration of disadvantaged residents, they lack middle-class-related infrastructures and thus have a poor reputation. While many traditional arrival neighbourhoods provide a diverse arrival-related infrastructure (from ‘ethnic’ food supplies via counselling facilities to community centres belonging to different religions), new arrival spaces in suburban and even rural areas are often characterised by a significantly lower supply/coverage of such infrastructure (Boost & Oosterlynck, 2019: p 154; Gardesse & Lelévrier, 2020).

The citywide role of arrival neighbourhoods and their interconnectedness with the housing market are being discussed not only in research, but also in recent years among policymakers and planners in various European countries. The influx of refugees has highlighted already existing and worsening housing bottlenecks, especially with regard to affordable housing. This applies in particular to many large cities that function as long-term migration destinations. Here, many migrant newcomers find their first foothold in arrival neighbourhoods where (affordable) housing market segments are easier to access.

Building on the interconnectedness of structure and agency, the focus on the production of neighbourhoods sheds light on how migration is governed and how arrival neighbourhoods are shaped. The perspective on (co-)production hints at the dynamic interplay of organisational practices and structures and their embeddedness in the local or regional context (Lang, 2019: 36). Such a perspective shifts the focus away from the (migrant) tenant towards local institutions and locally specific economic constraints, first and foremost dictated by the housing market. In contrast to the concept of collaboration, co-production does not necessarily relate to targeted or coordinated strategies, but also covers the simultaneous or even contradictory actions of stakeholders and their arrangements in a relational field of power. Studies such as that of Bassoli (2010) show that governance arrangements exist at different spatial levels and include both formal and informal practices and interaction between public and non-public stakeholders, as seen for example in the fields of housing provision for newcomers, brokering processes, ‘shadow economies’ and internal migration industries in (arrival) neighbourhoods (Bernt et al., 2022).

The production of arrival neighbourhoods is not just an academic question but also appears in policy and planning documents. Beginning in 2020, the topic is also increasingly finding its way into policy documents at national level, as reflected in the 2020 update of the National Action Plan on Integration (Die Bundesregierung, 2020) in which ‘arrival neighbourhoods’ are formally addressed by the German government for the first time, as well as being highlighted in the ‘Report of the Federal Government’s Expert Commission on the Framework Conditions for Integration Capacity’ (Fachkommission Integrationsfähigkeit, 2020). These documents emphasise the important citywide functions these neighbourhoods can have, insofar as they are equipped with sufficient resources. However, against the background of increasing social segregation and concerns about further societal polarisation in Germany, the notion of ‘arrival neighbourhoods’ is partly understood as a new label for ‘low-income neighbourhoods’, thereby reflating the fear of ‘parallel societies’/‘ghettos’. However, the processes contributing to the (co-)production of arrival neighbourhoods and the role played by the housing market are hardly ever addressed.

2.2 Migrants’ access to the German housing market: the role of housing providers and local governance

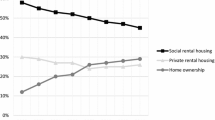

Accounting for 58% of the total housing stock (Statista Research Department, 2020), the German rental housing market suffers from two problems: a general housing shortage and a specific lack of affordable housing. Several studies point to a shortage of about 1 million apartments in Germany's major cities. About 270–280,000 apartments are built nationwide each year, though some 400,000 are the political goal (Rink & Egner, 2020: p 15). In addition, the larger share of new-built apartments serves affluent groups, while rising rents are reducing the segment of affordable apartments. Between 2006 and 2019, the number of social housing apartments dropped from 2.1 to 1.1 million (Statista Research Department, 2021) and is thus no longer able to meet demand from low-income households (Holm & Juncker, 2019).

Driven by the recent influx of refugees, housing bottlenecks have emerged and intensified, even forcing many refugees to stay living in temporary accommodation in several German cities. A recent study on the socio-spatial distribution of people with a migration background between 2014 and 2017 (Helbig & Jähnen, 2019) revealed that, in all 86 German cities studied, the proportion of migrants increased most in the socio-economically most disadvantaged neighbourhoods. Supply bottlenecks can create an environment fuelling discrimination: migrants face particular challenges in accessing housing, while quantitative testing studies provide proof of structural discrimination in the allocation process (Auspurg et al., 2017; Horr et al., 2018). Compared to other European countries, discrimination in the housing market remains quite a taboo subject in Germany, as illustrated by a recent statement on the National Action Plan on Integration of the housing industry umbrella organisation GdW. This concludes that there is “no systematic discrimination of people seeking an apartment with regard to the characteristics (age, gender, race etc.) set forth in the German Equal Treatment Act” (GdW, 2021: p 11, own translation).

Interestingly—and partly in contradiction to the debate on arrival neighbourhoods –, the influx of refugees has fuelled renewed interest in the political narrative of ‘mixing’ in various European countries such as the UK, France and Germany. In the sense of ‘spreading the burden’ (Darling, 2016: p 238), attempts are being made to avoid a greater concentration of migrant newcomers in neighbourhoods already strongly characterised by immigration by allocating them to specific locations (e.g., to rural areas). The goal of social mixing is pursued by different types of provider groups, ranging from municipal housing associations via housing cooperatives to private housing companies (Hanhörster & Ramos Lobato, 2021). While housing allocation policies in other European countries such as the UK and the Netherlands offer less leeway and thus less room for discrimination (Münch, 2009: p 448), housing reforms planned in Denmark explicitly aim at reducing the share of people of ‘non-Western’ origin in social housing to 30% within 10 years. In neighbourhoods on the so-called Danish ‘ghetto-list’, ‘non-Western’ residents can even be evicted from public housing (O’Sullivan, 2020).

In Germany, this planning practice is based on the guiding legal principle of ‘balanced population structures’ and ‘stable neighbourhoods’ enshrined in the German Building Code (e.g., BauGB § 1 and §171) and national strategic plans (Die Bundesregierung, 2007). The social mix principle is thus politically anchored, creating a framework for action for the various stakeholders involved and providing considerable room for manoeuvre for municipal stakeholders as well as housing providers and their allocation policies within the city. Municipal administrations in Germany can exert (some) influence on the spatial structure of the housing market and segregation. In addition to the use of classic urban development instruments (e.g., the ‘Social Cohesion’ programme), this influence also relates to their role (used to varying degrees) in providing municipal housing as well as controlling the occupancy of social housing (and of all other housing made available by other providers) through the right to allocate housing to special needs groups.

Housing providers pursue the ‘social stability’ planning paradigm in different spatial contexts. A key element of this paradigm are social mixing strategies. Concerning not only low-income (arrival) neighbourhoods, but also more affluent neighbourhoods, these often have the effect of disadvantaging those households (such as newcomers) perceived as ‘endangering’ stability (Münch, 2009). However, as we will show, there is no consistent understanding of the term ‘stability’ among stakeholder groups. In some cases, it refers to the aim of keeping fluctuation rates low, while in others it is explicitly related to a certain envisaged social mix. However, little research has been done on the extent to which ‘mixing’ strategies influence the development of arrival neighbourhoods. As mentioned above, these planning principles partly contradict a strengthened role of arrival neighbourhoods as a first point of entry for newcomers to a city and providing arrival-related infrastructures and housing specifically accessible for low-income groups in these areas (Haase et al., 2020).

3 Case studies and methods

3.1 Case studies selection and key characteristics

The analysis of arrival neighbourhoods in the three German cities Dortmund, Hanover and LeipzigFootnote 2 is based on a relational, comparative approach (Ward, 2010). We go beyond simply finding variations within a set of most similar cases (Tilly, 1984; Ward, 2010), aiming to distinguish between patterns that are system-specific—like migration into the formerly divided Germanies—and those that are universal, like the marketing strategies of large private housing companies. The relational position of a city within a region is a further relevant marker: while Leipzig is a relevant destination for newcomers in eastern Germany, Dortmund is a traditional ‘migration hub’ in western Germany.

Following the idea of the relational approach, we selected the neighbourhood in each city that assumes the most important function as an arrival neighbourhood. Through this ‘most similar’ sampling, we aim to find variations related to the housing market and its role in the production and reproduction of the neighbourhood’s function. An overlapping of ‘old and new layers of migration’ (Vertovec, 2015) characterises all three neighbourhoods, with the influx of migrant newcomers in recent years boosting population diversity in all of them. However, taking a deeper look, we find considerable differences among them. In-migration was initiated through different migration systems and thus from different source countries and in different numbers: guest workers came to Hanover and Dortmund in the 1960s and 70s mostly from Southern Europe, Turkey and the Maghreb, whereas smaller numbers of contract workers came to Leipzig mostly in the 1980s from Vietnam, Angola, Mozambique and Cuba. Further variations can be found related to the housing market (e.g., housing stock, rent levels, housing market dynamics), the arrival neighbourhoods’ location within the city as well as the availability of arrival-related infrastructures contributing to a certain attractiveness for newcomers. Language courses, shops offering international goods or money transfer services facilitate the initial orientation of newcomers while also providing informal support structures, such as shopkeepers who give their customers advice on where to find a vacant flat. Thus, while they are all termed as arrival neighbourhoods, they have different features—as specified below.

Located in the Ruhr city of Dortmund, the case study neighbourhood Inner-City North is a traditional working-class neighbourhood within walking distance of the main station and featuring a heterogeneous building stock. Compared to the city as a whole, the neighbourhood is characterised by a high concentration of income poverty. A recent influx of refugees and South-East European migrants has added a new layer to its long history of in-migration. A large number and variety of arrival-related infrastructures serve its highly diverse population. While the housing market in Dortmund has become much tighter in recent years, rental apartments are still easier to find in the Inner-City North than elsewhere in the city. More than two thirds of the neighbourhood’s housing stock is privately owned.

Sahlkamp-Mitte is a large housing estate built in the 1970s on Hanover’s northern periphery. Almost half of the housing stock is social housing owned by one private housing company. Ownership has changed hands several times in recent decades due to sales of the portfolio. Affordable rents contribute to the neighbourhood’s ‘attractiveness’ for migrants. Today, the neighbourhood is characterised by mainly two layers of migration—a first wave of refugees and late repatriates from the former Soviet Union in the early 1990s and a second wave of refugees mainly from Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan since 2013. Despite the relatively low density of (arrival-related) retail and service infrastructures, local stakeholders report that housing satisfaction in the neighbourhood is quite high.

In Leipzig, the Inner East—the two adjacent districts Volkmarsdorf and Neustadt-Neuschönefeld—serves as the case study. Built in the mid-nineteenth century, this formerly working-class area suffered from a lack of maintenance during GDR time, with subsequent high vacancy rates leading to its decay. Shrinkage peaked in the 1990s during the post-socialist transformation; moderate growth began in the 2000s and intensified in the 2010s, reflecting the neighbourhood’s special role for newcomers. Its growth and relational positioning are characterised by a high density of arrival-related infrastructures and a relatively high share of low-income households (see Table 1). Nowadays, with many different population ‘layers’—particularly migrant newcomers, students, young professionals, refugees and increasingly families with a higher social status—moving into the neighbourhood, the housing market has become increasingly contested.

With this selection as our basis, we aim to work out differences between these neighbourhoods, all three of which have the citywide function as the most relevant arrival neighbourhood, arriving at a more differentiated understanding of the influences of local governance arrangements as well as of the housing market with its players and system-specific characteristics on the co-production of arrival neighbourhoods.

Table 1 underlines the above-mentioned similarities and differences of the case studies. The data illustrates that all case study neighbourhoods are, compared to their respective cities, characterised by a high population density, a high proportion of people with a migration background and high fluctuation rates (regarding in- and out-movements). Furthermore, in all three neighbourhoods the poverty concentration (expressed as the proportion of welfare recipients) is about twice as high as citywide. In relation to each neighbourhood’s overall population, the share of in-moving foreignersis also above average.Footnote 3 All case study neighbourhoods are targeted by funding programmes (especially the Social Cohesion programme) aiming to improve their economic, social and urban development and strengthen local networks. Alongside these similarities resulting from the respective citywide roles of the case study neighbourhoods, Table 1 also illustrates their differences, as they vary considerably with regard to the extent of migrant concentration, population dynamics and poverty concentration.

3.2 Methods and sampling

Our study was based on a total of 32 interviewsFootnote 4 with people responsible for housing market-related issues in all three cities in various functions (15 in Dortmund, 8 in Hanover, 9 in Leipzig). These included housing providers as well as municipal representatives and civil society. Depending on the housing market structure in the respective city, representatives from private and municipal housing companies as well as housing cooperatives and private owners were included. Although the range of housing providers in Dortmund and Leipzig includes a large number of individual owners, the main focus of this paper is on institutional housing providers in order to better understand their organisational practices. The research team's knowledge of the three cities and their ongoing involvement in stakeholder networks in all three over a period of more than three years facilitated the identification and recruitment of relevant interviewees.

The semi-structured interviews contained qualitative open questions on the citywide housing market as well as on the case study neighbourhoods, with a focus on migrants’ access to housing. We asked the interviewees about opportunities and challenges of the respective case study neighbourhoods and reasons for newcomers settling there. Furthermore, the interview guidelines contained questions on stakeholders’ local strategies and governance arrangements as well as the expected future development of the neighbourhoods, adapted to the roles and responsibilities of interviewees. All interviews were recorded, transcribed, and analysed using theoretical coding. As a quality control measure, we interpreted and discussed the data and codings among the team of authors.

The research subject is sensitive in that it addresses issues of discrimination and disadvantage. We are aware that this might have limited the willingness of stakeholders to openly answer certain questions. Especially representatives of private housing companies might not have fully disclosed their strategies and/or might have answered the questions in a socially desirable way or based on standardised responses. To compensate for the expected response bias, we triangulated the information by including not only private housing companies but also municipal officials and civil society representatives. As several requests for interviews with individual owners were declined, their perspective is mostly represented through interviews with civil society players (such as local tenant associations).

4 The co-production of arrival neighbourhoods by different stakeholders

As the following analysis shows, arrival neighbourhoods are not only produced by the respective cities’ and neighbourhoods’ structural conditions (such as the regional housing market) but are co-produced by stakeholders’ distinct strategies. To identify specific strategies of different players, we structure our findings in the following according to different housing market stakeholders. While the first sub-sect. (4.1) looks at housing providers, the following sub-sections focus on (4.2) municipalities’ and (4.3) non-governmental organisations’ roles in co-producing arrival neighbourhoods.

4.1 The co-production of arrival neighbourhoods by housing providers

One major reason behind the concentration of newcomers in the three arrival neighbourhoods under study is the locally concentrated stock of affordable and/or accessible housing. ‘Non-investment’ strategies practiced by the private sector (both institutional and individual housing providers) play a role in the production of arrival neighbourhoods as these lead to low-income groups moving into these stocks. In Hanover and Dortmund, investment backlogs have resulted in several housing units being in a comparatively poor state. In Dortmund’s Inner-City North, certain properties have even gained media attention as ‘run-down housing’ rented out mainly to newly arrived tenants from Southeast Europe at ‘discriminatory rents’ (NGO: Tenants’ association, Dortmund). The housing market in Leipzig is simultaneously experiencing ‘non-investment’ and upgrading. In Leipzig’s Inner East, the booming housing market is leading to speculative vacancies and recurring sales of (vacant) housing units. Due to these market dynamics, migrant tenants are struggling to find affordable housing, with the result that the district is slowly losing its function as an arrival neighbourhood (Haase et al., 2020).

The allocation of scarce housing is closely linked to housing providers’ tenant selection strategies and associated discriminatory practices. All housing providers we talked to underline the challenges of arrival neighbourhoods, such as a high concentration of income poverty. They fear that using the term in local debates may be associated with a further stigmatisation of the respective neighbourhood and consequently see the risks of decreasing property values and achievable rent levels. As various interview partners in all three cities reported and research in other German cities underlines (Hanhörster/Ramos Lobato 2021), indicators pointing to a migrant background (e.g., name, physical appearance, religion, language, residence status) lead to discrimination to varying degrees, consciously or unconsciously, among all types of housing providers: “Indeed, discrimination does exist, even of people who have lived here for generations. Discrimination occurs mainly when several criteria come together, such as social status, migration background, or especially a visible migration background of Arab or African originFootnote 5” (Municipality: social services, Dortmund). But as we will show below, this happens to a varying degree among housing providers. These allocation strategies concern the housing stock in arrival neighbourhoods but especially in more affluent parts of the city. Housing providers thus have an influence on both the accessibility of arrival neighbourhoods and the permeability of the overall housing stock. Thus, newcomers also have the opportunity to leave arrival neighbourhoods in the process of their social mobility.

Regarding the accessibility of arrival neighbourhoods, small private housing companies and private landlords are reported to apply more selective and partly discriminatory allocation practices: “When you approach private landlords, they have a lot of prejudices, as can be confirmed by many migrants seeking housing” (Housing provider: migrant landlord, Dortmund). Compared to bigger private housing companies, individual owners in all three cities put a greater focus on long-term and stable tenancies in their renting strategies. Although they form a fragmented and hardly coordinated group, the sum of their individual decisions influences the local situation, especially in Dortmund and Leipzig where they account for a large share of the housing market in the arrival neighbourhoods. According to an academic expert in Leipzig, the reasons for this enhanced selectivity may be racial prejudices: migrants are mostly associated with being ‘poor’ and ‘different’. In the eyes of individual landlords, the risk of neighbourhood conflicts may lead to increased fluctuation und thus to more effort and costs. As the German General Equal Treatment Act (Allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz, Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency, 2006) only applies to housing providers with more than 50 housing units, it allows private landlords to turn down applicants on the basis of their race, their names or other (visible) signs of difference.

Interestingly, in all case study neighbourhoods, large private housing companies reportedly enable access for low-income groups, guided not by a specific tenant mix but by profit maximisation and the certainty that the rents of low-income tenants will be paid by the city administration. Companies with large portfolios in arrival neighbourhoods are responding to the high turnover in their portfolios by renting out units as quickly as possible and with few allocation barriers. This seems to be the situation across our case studies, as interviews in Hanover and Dortmund illustrate: “[T]he large companies: Deutsche Wohnen, Vonovia – they don’t do such screening. They just rent out apartments” (NGO: housing initiative, Hanover), “Well, the bigger housing companies allocate housing from a more distant and objective perspective” (Housing provider: migrant landlord, Dortmund). As reported by one interviewee from a large private housing company, tenants are only turned down if they have rent debts from previous tenancies with the same housing company (Housing provider: large private housing company, Hanover). Thus, as their allocation practices are not very selective, their housing stock is more accessible to low-income newcomers.

Some interview partners, such as tenant association representatives or neighbourhood-based initiatives, refer to substantial barriers in the housing market especially in more affluent neighbourhoods, leading also to involuntary segregation in arrival neighbourhoods. As argued in sect. 2, this is especially interesting against the background of housing companies’ interest in following the paradigm of neighbourhood stability. As declared in an interview with a representative of a housing company in Dortmund, such ‘stabilisation’ practices can in practice lead to tenants with a migration background being rejected in more affluent areas: Staff in charge of tenant selection decide on the ‘right’ mix for the respective areas based on personal estimations and ‘experience’, making the process highly arbitrary. The impeded access to privileged neighbourhoods affects not only those seeking housing, but also those acquiring property. Having a migrant living next door is associated with a decrease in property value: “Yesterday we had a conversation with a colleague [with a migration background] who owns a house next door to a dentist. Another colleague said to him: `Your house is worth more than the dentist’s house. ‘Why?’ he asked. ‘You have a house next to the dentist and they have a house next to Turks’” (Housing market representative: real estate agent, Dortmund).

Summing up, the ‘stable neighbourhood’ planning paradigm (followed by many individual housing providers) in arrival neighbourhoods seems to legitimise and thus to hide racial discrimination on the housing market, whereas the market-driven approach adopted by large private housing companies surprisingly shows lower potential for discriminatory practices. Furthermore, the intention of some housing providers to ensure social stability in more affluent neighbourhoods partly causes migrants ‘involuntary’ segregation in arrival neighbourhoods, thereby reducing the permeability of the housing market.

4.2 The co-production of arrival neighbourhoods by municipalities

All three city administrations acknowledge that the neighbourhoods concerned fulfil important arrival functions for the city as a whole and enable many migrants to gain a foothold in society. However, while they consider the functions of arrival neighbourhoods as important, they stress the necessity of social and ethnic mixing: “People become alienated from each other if the social mix is not there. Like when there is a house with ten flats and seven Turkish tenants live there. (…). Of course, that is counterproductive. It doesn't promote integration” (Municipality: municipal housing company representative, Hanover). The neighbourhood’s ‘stability’ is not essentially seen in its continuing function as an arrival neighbourhood. Rather, as the quote and the following sub-section illustrate, stability is understood in the sense of the guiding paradigm of a social mix, avoiding overly high concentrations of poverty and diversity. This is supported by the Hanover city administration which views mixing as a suitable means of avoiding ‘problematic neighbourhoods’ (Municipality: city administration, Hanover). Similarly, in Dortmund and Leipzig, social and ethnic mixing is seen as an opportunity to upgrade neighbourhoods.

The shrinking social housing stock reduces municipalities’ room for manoeuvre in the provision and spatial distribution of housing for low-income households. As in most large cities, our case study neighbourhoods are characterised by a shrinking stock of social housing. Dortmund, for example, has 24,000 social housing units, but 90,000 eligible households (among them many migrant newcomers) (Stadt Dortmund, 2020: p 43). Social housing accounts for only a small percentage of the housing stock in the Inner-City North. By contrast, social housing policies play an important role in Sahlkamp-Mitte, where the city holds voucher rights for 400 of the 820 housing units of the private housing company. High in comparison to the rest of the city, these rights help maintain the neighbourhood’s arrival functions.

In Leipzig, the municipal housing company sold off a large share of its housing stock, intensifying housing supply concerns. However, in 2020 the city mandated the municipal housing company to earmark 30 per cent of the housing stock in the Inner East for migrants to counter any further displacement of the resident population by ongoing gentrification. For a long time, the city did nothing against rising Inner East rents and threats of displacement. While the current interventions come late, they might still have a considerable impact on the neighbourhood’s arrival function. One example of interventions to protect low-income tenants and prevent the displacement of the resident population is the city’s adoption of a preservation statute in 2020. However, Leipzig’s current economic boom and its increasingly contested housing market make it unrealistic to hope for the municipality to gain more control and opportunities to intervene: “I believe that the dynamics of this development cannot be stopped completely. [In my view] upgrading will continue, especially in the part of Leipzig’s Inner East closest to the city centre. And depending on how the city as a whole develops, it will go faster or slower” (Municipality: neighbourhood manager, Leipzig).

A municipality’s influence on the development of arrival neighbourhoods derives not only from its own housing stock but also from its cooperation with other housing providers. The three city administrations reported on their differing efforts to cooperate with private housing companies. As regards large companies, municipalities are in many cases hardly able to exert influence on strategies as such companies act first and foremost in the interest of their (international) shareholders. Our example of Hanover Sahlkamp shows, however, that the municipality has some influence on the largest private owner in the neighbourhood through occupancy rights. Cooperation between city administrations and private companies is voluntary and depends on the ‘goodwill’ of the respective company. Municipal stakeholders in all three cities considered it a problem that the fragmented and diverse group of individual landlords is difficult to reach. One important consequence is that discriminatory practices in housing allocation are under the city's radar.

In the case of Dortmund, developing the housing market through cooperation with private owners forms part of an integrated social planning approach linking the activities of different municipal departments. Such cooperation prevents a downward spiral, thus promoting the area’s long-term perspective as an arrival neighbourhood. The case of Dortmund shows that long-term and reliable cooperation between housing providers under the leadership of the municipality can establish a strong foundation for housing market development. One municipal cooperation project supports a corporate identity for the Inner-City North, shaping the feeling that ‘all act in concert’: “Thanks to [the project], housing providers have become aware that it is definitely worth investing in the development of their existing housing stock or in new construction projects in the north of Dortmund—and that they are committed to neighbourhood development overall.” (Municipality: housing department, Dortmund). In contrast to this, in Hanover Sahlkamp, cooperation with the private housing provider is described by the municipality as ‘extremely limited’. In Leipzig, many forms of cooperation emerged in the period of shrinkage with its high vacancy rates. Under these conditions, housing providers had a keen interest to cooperate, while in the current (re)growth period, private players in particular have reverted to following their (market-driven) interests.

4.3 The co-production of arrival neighbourhoods by NGOs

Importantly, the (co-)production of arrival neighbourhoods involves not only housing providers and the municipality, but also stakeholders from civil society. NGOs influence the development of arrival neighbourhoods in two ways: (a) the needs-based development of arrival-related infrastructures and the implementation of urban services, and (b) their role in shaping discourse at different spatial levels.

In contrast to most housing providers and partly also city administrations, civil society representatives describe the concentration of arrival-related infrastructures, ranging from ethnic shops to language courses, as an important asset. Such infrastructures are sometimes specialised with respect to the needs of newcomers and often provided by NGOs, such as migrant self-help organisations. Some NGOs operate at the intersection of ‘housing’ and ‘integration’, implementing their broader understanding of ‘fair housing’ on the ground. In all three case study neighbourhoods, we find diverse (mostly publicly funded) opportunity structures including social and counselling infrastructures enabling migrant newcomers to settle and navigate the housing market.

To maintain arrival neighbourhoods as facilitating environments for migrant newcomers, some stakeholders expressed the need for support initiatives and networks mediating between tenants and landlords. In Hanover Sahlkamp, one municipal project provides legal support for tenants, financed by the city and administered by an intermediary. The project supports communication and conflict-solving between landlords and tenants, helps with day-to-day red tape, provides advice and supports tenants’ interests in cases of conflict. Particularly for tenants with a migration background, this project is of great help due to their lack of knowledge of the German housing market structure and rental system, but also due to language barriers or lacking communication skills: “If a tenant has a burst pipe in her apartment and calls [the landlord], nothing happens. When we call, someone comes immediately” (NGO: project providing legal support for tenants, Hanover). In Dortmund, the role of tenant associations is very strong. In cooperation with neighbourhood associations, their role has become even stronger; one project for example takes on a mediating role between disadvantaged residents (e.g., members of the Roma community), the municipality and housing owners, in particular in complicated cases of run-down housing. The strategy to strengthen the position of tenants through providing them with information and upholding their rights vis-à-vis landlords is also being pursued in Leipzig, where a local network was established in 2020 in the Inner East to support tenants in case of conflicts with municipal, civil society and intermediary housing players as well as the municipal housing company.

Working partly on behalf of municipalities, NGOs take on an intermediary role in implementing municipal goals on the ground by contributing their local and target-group-specific knowledge. Our civil society interview partners stressed that a common understanding of arrival neighbourhoods’ strengths and challenges is needed to facilitate the arrival and settlement of newcomers. In Dortmund and Leipzig, municipal strategic planning is increasingly carried out in close cooperation with NGOs. However, this also points to the difficult role of NGOs in balancing their own values and commitment with possible instrumentalisation by the municipality. This also regards municipal agenda-setting in arrival neighbourhoods and debates about resources needed. Instead of fearing, as many representatives from the city and the housing industry do, that a concentration of infrastructures could attract even more newcomers, they clearly advocate strengthening the potential of arrival neighbourhoods.

Local civil society representatives reported the diverse composition of arrival neighbourhoods and/or the high share of people with migration backgrounds as contributing to newcomers’ ‘feeling of home’. With ethnic diversity part of everyday live in the Inner-City North (Hans/Hanhörster 2020: p 82), one interview partner referred to the neighbourhood as being less hostile than other parts of Dortmund: “Many people do not want to live in the southern [more privileged and less ethnically diverse] parts of the city because they experience people looking at them in a strange way. That too is to be understood as discrimination. In the Inner-City North, it is easier for different cultures to live together.” (Municipality: city administration, Dortmund). Based on their clients’ narratives as well as individual experiences, our interview partners were very aware of discriminatory practices: “My brother-in-law’s surname is IbrahimFootnote 6 but my sister’s surname, his wife, is Obermüller. And every time she called for a flat, it was available, but when he called, it was already rented out.” (NGO: head of a mosque, Hanover). However, although discriminatory practices were identified by NGOs as an issue in all three case study neighbourhoods, access restrictions were hardly publicly debated (cf. Hanhörster & Ramos Lobato, 2021). One major methodical drawback is that the discriminatory practices of housing providers are hardly empirically verifiable and therefore difficult to address (cf. Horr et al., 2018).

While networking and lobbying play an important role, arrival neighbourhoods need, as some of our interview partners stressed, sustained support in the form of financial and human resources to back their important citywide function. However, many support structures suffer from a lack of personnel and time for dealing with their clients. This support is also lacking with regard to strengthening migrants’ positions on the housing market (demand-oriented affordable housing and counteracting discrimination), as shown by studies focused on Leipzig, Dortmund and Hanover (Rink & Egner, 2020; Werner et al., 2018). Up to now, only few representatives of migrant groups have been integrated in the governance structures created at municipal level in recent years.

5 Discussion

This section discusses the key findings presented in sect. 4 in the context of theoretical perspectives presented in sect. 2.

5.1 Strengthening newcomers’ arrival or working towards neighbourhood stability: a contradiction?

The portrayed arrival neighbourhoods are characterised (to varying degrees) by the income poverty of their residents. Thus, the way the interviewed stakeholders handle these neighbourhoods is closely linked to their concerns about a (further) concentration of poverty. Strengthening the function of arrival neighbourhoods (in terms of strengthening their accessibility for newcomers) seems to contradict housing providers’ and municipalities’ understanding of creating ‘stable neighbourhoods’. Or, to put it in other words, ‘stability’ in the understanding of these stakeholder groups (and in some cases also of people with a migration background) refers to a low level of fluctuation and a low concentration of poverty rather than—as the perspective of interviewees from NGOs suggest—to stability in a neighbourhood’s citywide function as an arrival neighbourhood over a longer period of time.

While municipal housing companies have a mandate to provide housing to low-income groups, this goal seems to partly interfere with the aim of stabilising neighbourhoods under the reigning ‘social mix’ planning paradigm. For the researched municipalities, ‘stabilisation’ provides the legal basis for engineering the ‘right’ mixing of tenants from different social and/or cultural backgrounds. This approach assumes that having rental properties occupied by ‘problematic’ tenants has a negative effect on social relationships between tenants.

Concerns over neighbourhood instability are reflected in a city administration’s interest in controlling an area’s residential composition through a stronger tenant mix. The ‘social mix’ paradigm, however, generates concerns among civil society as it may be used to conceal or legitimise discriminatory practices in tenant selection. The topicality and explosiveness of municipal’mixing’ strategies become clear when looking at Danish housing policy and the country’s drastic set of policies in disadvantaged areas classified by the government as ‘ghettos’ (O’Sullivan, 2020). Interestingly, the profit maximisation strategies of private housing companies (as seen in the example of Hanover) seem to partly counteract discrimination regarding housing accessibility in arrival neighbourhoods. The concentration of poverty is accepted because housing costs are ‘safe’, being underwritten by the municipal welfare budget. The market-oriented approach of large private housing companies thus seems to have a surprisingly paradoxical effect, namely to be less prone to discrimination. However, this clearly happens at the expense of the housing standards of the most vulnerable seekers and against the background of rent payments guaranteed by the public sector. This strategy of rent maximisation should be viewed critically, especially when the citywide housing market is not permeable, preventing migrants and other city-dwellers (in the course of their housing career) from renting flats in a more affluent area.

In Leipzig, the Inner East has been positively promoted and publicly advertised as a ‘diverse neighbourhood’ since the mid-2000s. This case shows that, although the perception of the status quo is similar among the interviewed housing providers and neighbourhood initiatives, the dynamics of upgrading are evaluated differently. While private owners hope for upgrading and rising rents, municipal and civil society players point to the risk of increasing segregation and displacement. Against this background, concerns are raised about the possible influx of more advantaged residential groups. Subsequently, some municipal and civil society players in Leipzig are not pursuing the goal of mixing but instead investing effort in maintaining the status quo.

To sum up, arrival neighbourhoods can take on an important citywide role in enabling newcomers to gain a foothold in a city. They can play this role successfully (in the sense of migrants’ arrival and moving on) if three criteria are fulfilled: housing is accessible/affordable for low-income groups, they are equipped with infrastructures helping newcomers to gain a foothold, and the city-wide housing stock is permeable regarding residents’ relocation to other neighbourhoods. All three criteria refer to a neighbourhood’s embeddedness in the wider housing market (El-Kayed et al., 2020).

5.2 The co-production of arrival neighbourhoods?

Our evidence shows that it is not just the sum of players’ strategies, but their interplay and distinct local governance arrangements which co-produce arrival neighbourhoods. These arrangements are shaped by housing providers (different types and with differing scales of operations), city administrations and intermediary players (NGOs, social services etc.).

Accessibility of housing market subsegments is a sine qua non for the emergence and functioning of arrival neighbourhoods. Housing market stakeholders specifically influence the accessibility and permeability of arrival neighbourhoods and thus (co-)produce these areas through different strategies: 1. discriminatory allocation practices both in arrival neighbourhoods and in more affluent areas, 2. non-investment strategies leading to downgrading and/or 3. upgrading strategies targeting higher-income (German) middle-class households and excluding lower-income households (migrant and non-migrant). With housing allocation and its effects on vulnerable population groups in Germany still an under-researched topic, more attention is required on the part of municipalities or housing umbrella organisations. As described for all three cities, the partly inconsistent understanding of the arrival function itself makes it difficult to adopt a coherent approach in the sense of strengthening neighbourhood potentials and opportunities for migrant newcomers to access housing.

Furthermore, municipal players have little room for manoeuvre. Despite the efforts of various municipal policymakers, housing officials and civil society, the strengthening of arrival neighbourhoods remains constrained by the low willingness of private providers to cooperate. This is also reflected by the fact that private housing companies are reluctant to make their allocation strategies transparent, meaning that we can only include other stakeholders’ perspectives on their strategies. Many civil society, intermediary or municipal support infrastructures and players operate precariously and are increasingly overburdened by the pure scope of support needs. At a more general level, property speculation, upgrading and a significant rise in rents represent challenges which cannot fully be counteracted at local level. Against the backdrop of rapidly rising rents, long-term leases are no longer necessarily of interest to landlords. This may also have an impact on fluctuation and continuously rising rents in the future. Thus, our case studies illustrate that co-production has to be understood as a close processual interplay between structure and agency (Lang, 2019): Housing market stakeholders’ strategies and their institutional as well as spatial embeddedness in larger structures co-produce arrival neighbourhoods.

5.3 Spatial and temporal dynamics of arrival neighbourhoods

Through the synopsis of the three neighbourhoods in three different cities, it became clear that arrival neighbourhoods underlie very different spatial and temporal dynamics. Dortmund’s Inner-City North has managed to maintain its function as a ‘stable’ arrival neighbourhood over a period of several decades. Due to its comparably affordable and accessible housing stock, experts expect it to continue serving as a first point-of-entry. In Hanover Sahlkamp, we are seeing the emergence of a new arrival neighbourhood with few social (arrival) infrastructures. Having emerged under the specific conditions of post-socialist shrinkage, the arrival neighbourhood in Leipzig’s Inner East is now booming (Haase et al., 2020). Due to neighbourhood renewal and upgrading, the neighbourhood might gradually lose its arrival function for low-income groups.

Against this background, it is worth taking a systematic look at factors and constellations favouring the production of arrival neighbourhoods in cities as well as those endangering their functioning. Our findings show that the dynamics of arrival neighbourhoods are embedded in citywide housing market dynamics and in general housing market developments, i.e., housing costs and their distribution, property market developments, available land resources, etc. Therefore, arrival neighbourhoods need to be contextualised holistically on a citywide scale and in a long-term perspective, as a number of studies already suggest (e.g., Dunkl et al., 2019). While the focus of this article is on arrival neighbourhoods located in large cities, it will be interesting for future research to take a closer look at arrival neighbourhoods outside metropolitan areas (which in Germany have increased in number due to the influx of refugees as of 2015 and again 2022).

6 Conclusion

In our paper, we have dealt with the questions of how arrival neighbourhoods are (co-)produced by housing providers, and how they are embedded in local governance structures. We arrive at the general conclusion that arrival neighbourhoods fulfil important functions on a citywide scale, offering the accessible and affordable housing crucial to newcomers. Accessibility, affordability and permeability (relating to a neighbourhood’s embeddedness in the city) and a neighbourhood’s arrival-specific amenities and networks are thus the most important prerequisites allowing it to function as an arrival neighbourhood. Once one of the prerequisites loses in importance or even disappears, the neighbourhood’s function changes.

Arrival neighbourhoods are produced both by (more or less deliberate) action by different housing providers and by contextual factors such as general housing market developments or migration dynamics. Thus, both agency and structural dimensions closely interact. As players like city administrations, private housing companies and individual landlords often follow different interests, their interplay and local governance reveal partly contradictory interests and conflicts. For example, private housing companies’ interest in generating profits partly leads to a concentration of poverty in arrival neighbourhoods. We have demonstrated that urban policymakers are guided by their interest to stabilise urban neighbourhoods and to keep them as attractive housing and living locations. However, this may not go hand-in-hand with a strengthening of the arrival function, as the national planning paradigm of creating stable neighbourhoods tends to be understood in a social mix sense, rather than in ensuring an area’s citywide function as an arrival neighbourhood.

The example of Leipzig shows how the upward dynamics of an arrival neighbourhood (welcomed by the housing industry) can have detrimental consequences for the accessibility of the housing market for migrant newcomers. In tight housing markets, new arrival neighbourhoods can be expected to emerge in lower-priced but mostly peripherally located housing stock. The example of Dortmund shows that the ‘stable’ functioning of an arrival neighbourhood is conducive to ‘accessible’ housing markets and spatially concentrated arrival-related opportunity structures. However, it is important to strengthen the permeability of the entire housing market. There is a need for critical discourse on the guiding principles of ‘social stability’ and ‘social mix’ and their (unintended) discriminatory consequences. This is particularly important in Germany, where discrimination has so far been more tabooed and less monitored (for example by the housing industry umbrella organisation) than in other countries.

Thus, the strengthening of an arrival neighbourhood’s function not only depends on ownership structures but also on municipal housing providers’ and civil society organisations’ capacities, strategic goals and will for (concerted) action. The importance of civil society and intermediary players in exposing and taking action against discriminatory housing allocation practices must not be underestimated. A serious problem for the successful governance of arrival neighbourhoods is the limited readiness of housing providers, especially private ones, to cooperate.

Data availability

All interview partners were assured of anonymity for their participation in this study; it is therefore not possible to pass on the raw interview data to readers of the article. If requested, the transcripts will be made available to the reviewers.

Notes

In the following, when using the term ‘migrants’ we refer to the definition of the German Federal Statistical Office, which states that a person has a migration background if s/he has at least one parent not born in Germany (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2021).

Funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research, the three case studies are part of a research project dealing with cooperative open space development in arrival neighbourhoods.

For the case study in Hanover, this data is only available at the district level. Based on interviews with local experts, it can be assumed that the rates for the sub-district Sahlkamp-Mitte are significantly higher.

All interviews were conducted in German and translated by the authors.

All quotes are translated by the authors.

To preserve anonymity, all names are pseudonymised.

References

Aalbers, M. B. (2016). The financialization of housing. Routledge.

Ager, A., & Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies, 21(2), 166–191.

Amelina, A. (2017). After the Reflexive turn in migration studies: Towards the doing migration approach. Working Paper Series “Gender, Diversity and Migration” 13/2017.

Arbaci, S. (2007). Ethnic segregation, housing systems and welfare regimes in Europe. European Journal of Housing Policy, 7(4), 401–433.

Auspurg, K., Hinz, T., & Schmid, L. (2017). Contexts and conditions of ethnic discrimination: Evidence from a field experiment in a German housing market. Journal of Housing Economics, 35, 26–36.

Bassoli, M. (2010). Local governance arrangements and democratic outcomes (with some evidence from the Italian case). Governance, 23(3), 485–508.

Bernt, M., Hamann, U., El-Kayed, N., & Keskinkilic, L. (2022). Internal migration industries: Shaping the housing options for refugees at the local level. Urban Studies, 59(11), 2217–2233.

Boost, D., & Oosterlynck, Stijn. (2019). “Soft” urban arrival infrastructures in the periphery of metropolitan areas: The Role of social networks for sub-Saharan newcomers in Aalst, Belgium. In B. Meeus, K. Arnaut, & B. van Heur (Eds.), Arrival infrastructures: Migration and urban social mobilities (pp. 153–178). Palgrave Macmillan.

Darling, J. (2016). Asylum in austere times: Instability, privatization and experimentation within the UK asylum dispersal system. Journal of Refugee Studies, 29(4), 483–505.

Die Bundesregierung. (Ed.) (2007). Der Nationale Integrationsplan: Neue Wege, neue Chancen.

Die Bundesregierung (Ed.) (2020). Nationaler Aktionsplan Integration der Bundesregierung.

Dill, V., & Jirjahn, U. (2014). Ethnic residential segregation and immigrant’s perceptions of discrimination in West Germany. Urban Studies, 51(16), 3330–3347.

Stadt Dortmund, Amt für Wohnen (2020). Wohnungsmarktbericht 2020. Ergebnisse des Wohnungsmarktbeobachtungssystems 2019. Retrieved August 3, 2021 from https://www.dortmund.de/media/p/wohnungsamt/downloads_afw/Wohnungsmarktbericht_Dortmund_2020.pdf

Dunkl, A., Moldovan, A., & Leibert, T. (2019). Inner-städtische Umzugsmuster ausländischer Staatsangehöriger in Leipzig: Ankunftsquartiere in Ostdeutsch-land? Stadtforschung Und Statistik: Zeitschrift Des Verbandes Deutscher Städtestatistiker, 32(2), 60–68.

El-Kayed, N., Bernt, M., Hamann, U., & Pilz, M. (2020). Peripheral estates as arrival spaces? Conceptualising research on arrival functions of new immigrant destinations. Urban Planning, 5(3), 103–114.

Fachkommission Integrationsfähigkeit (Ed.) (2020). Gemeinsam die Einwanderungsgesellschaft gestalten. Bericht der Fachkommission der Bundesregierung zu den Rahmenbedingungen der Integrationsfähigkeit. Bundeskanzleramt.

Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency (2006). Allgemeines Gleichbehandlungsgesetz (AGG) [German general equal treatment act]. Federal Anti-Discrimination Agency.

Fields, D., & Uffer, S. (2016). The financialisation of rental housing: A comparative analysis of New York City and Berlin. Urban Studies, 53(7), 1486–1502.

Fonseca, M. L., McGarrigle, J., & Esteves, A. (2010). Possibilities and limitations of comparative quantitative research. Housing Studies, 17(3), 381–399.

Gardesse, C., & Lelévrier, C. (2020). Refugees and asylum seekers dispersed in non-metropolitan French cities: Do housing opportunities mean housing access? Urban Planning, 5(3), 138–149.

GdW (Bundesverband deutscher Wohnungs- und Immobilienunternehmen e.V.) (2021, March 3): Position Integration und Diskriminierung Nationaler Aktionsplan Integration NAP-I. 13. Integrationsgipfel am 09.03.2021. Retrieved August 9, 2021, from https://www.gdw.de/media/2021/03/gdw_position_nap-i_-integrationsgipfel_09.03.2021_final.pdf

Gerten, C., Hanhörster, H., Hans, N., & Liebig, S. (2022). How to identify and typify arrival spaces in European cities - A methodological approach. Population, Space and Place, e2604. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2604

Grzymala-Kazlowska, A., & Phillimore, J. (2017). Introduction: Rethinking integration. New perspectives on adaptation and settlement in the era of superdiversity. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(2), 179–196.

Haase, A., Schmidt, A., Rink, D., & Kabisch, S. (2020). Leipzig’s inner east as an urban arrival space? Exploring the trajectory of a heterogeneous inner-city neighbourhood in an East German city. Urban Planning, 5(3), 89–102.

Hanhörster, H., & Ramos Lobato, I. (2021). Migrants’ access to the rental housing market in germany: housing providers and allocation policies. Urban Planning, 6(2), 7–18.

Hanhörster, H., & Wessendorf, S. (2020). The role of arrival areas for migrant integration and resource access. Urban Planning, 5(3), 1–10.

Hans, N., & Hanhörster, H. (2020). Accessing resources in arrival neighbourhoods: How foci-aided encounters offer resources to newcomers. Urban Planning, 5(3), 78–88.

Helbig, M. & Jähnen, S. (2019). Wo findet 'Integration' statt? Die sozialräumliche Verteilung von Zuwanderern in den deutschen Städten zwischen 2014 und 2017. WZB Discussion Paper No. P 2019–003.

Holm, A. & Junker, S. (2019, March). Die Wohnsituation in deutschen Großstädten–77 Stadtprofile. Retrieved August 19, 2021, from https://www.boeckler.de/pdf_fof/100892.pdf

Horr, A., Hunkler, C., & Kroneberg, C. (2018). Ethnic discrimination in the German housing market. A field experiment on the underlying mechanisms. Zeitschrift für Soziologie, 47(2), 134–146.

Kohlbacher, J. (2020). Frustrating beginnings: How social ties compensate housing integration barriers for afghan refugees. Urban Planning, 5(3), 127–137.

Kreichauf, R., Rosenberger, O., & Strobel, P. (2020). The transformative power of urban arrival infrastructures: Berlin’s Refugio and Dong Xuan Center. Urban Planning, 5(3), 44–54.

Lang, C. (2019). Die Produktion von Diversität in städtischen Verwaltungen. Wandel und Beharrung von Organisationen in der Migrationsgesellschaft. Springer VS.

Meeus, B., van Heur, B., & Arnaut, K. (2018). Migration and the infrastructural politics of urban arrival. In B. Meeus, K. Arnaut, & B. van Heur (Eds.), Arrival infrastructures: Migration and urban social mobility (pp. 1–32). Palgrave Macmillan.

Statistisches Bundesamt (Ed.) (2021). Migration und Integration. Migrationshintergrund. Retrieved May 18, 2021, from https://www.destatis.de/DE/Themen/Gesellschaft-Umwelt/Bevoelkerung/Migration-Integration/Glossar/migrationshintergrund.html

Münch, S. (2009). “It’s all in the mix”: Constructing ethnic segregation as a social problem in Germany. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 24(4), 441–455.

O’Sullivan, F. (2020, March 11). How Denmark's 'ghetto list' is ripping apart migrant communities. Retrieved August 3, 2021 from https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/11/how-denmarks-ghetto-list-is-ripping-apart-migrant-communities

Park, R. E. (1915). The City: Suggestions for the investigation of human behavior in the city environment. American Journal of Sociology, 20(5), 577–612.

Rink, D. & Egner, B. (2020): Lokale Wohnungspolitik. Beispiele aus deutschen Städten. Nomos.

RWI & ImmobilienScout24 (2021). RWI-GEO-RED: RWI Real Estate Data (Scientific Use File)- apartments for sale. https://doi.org/10.7807/immo:red:wk:suf:v4

Saunders, D. (2010). Arrival cities. How the largest migration in history is reshaping our world. Pantheon Books.

Schillebeeckx, E., Oosterlynck, S., & De Decker, P. (2018). ’Migration and the resourceful neighborhood: Exploring localized resources in urban zones of transition’. In B. Meeus, K. Arnaut, & B. Van Heur (Eds.), Arrival infrastructures: Migration and urban social mobilities (pp. 131–152). Palgrave Publishers.

Statista Research Department (2020, September 24). Statistiken zum Thema Wohnen. Retrieved August 19, 2021, from https://de. statista.com/themen/51/wohnen

Statista Research Department (2021, June 8). Sozialwohnungen in Deutschland bis 2019. Retrieved August 19, 2021, from https://de.statista.com/statistik/daten/studie/892789/umfrage/sozialwohnungen-in-deutschland

Tilly, C. (1984). Big structures, large processes, huge comparisons. Russell Sage Foundation.

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 30(6), 1024–1054.

Vertovec, S. (2015). Introduction: Migration, cities, diversities ‘old’ and ‘new.’ In S. Vertovec (Ed.), Diversities old and new (pp. 1–20). Palgrave Macmillan.

Ward, K. (2010). Towards a relational comparative approach to the study of cities. Progress in Human Geography, 34(4), 471–487.

Werner, F., Haase, A., Renner, N., Rink, D., Rottwinkel, M., & Schmidt, A. (2018). The local governance of arrival in Leipzig: Housing of asylum-seeking persons as a contested field. Urban Planning, 3(4), 116–128.

Wessendorf, S. (2018). Pathways of settlement among pioneer migrants in super-diverse London. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(2), 270–286.

Wiest, K. (2020). Ordinary places of postmigrant societies: Dealing with difference in West and East German neighbourhoods. Urban Planning, 5(3), 115–126.

Wijburg, G., Aalbers, M. B., & Heeg, S. (2018). The financialisation of rental housing 2.0: Releasing housing into the privatised mainstream of capital accumulation. Antipode, 50(4), 1098–1119.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. This research was funded by the German Federal Ministry for Education and Research (BMBF).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The authors agree to the publication of the submitted manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethics approval Consent

The authors assure that the research conducted meets all ethical standards of the journal.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hanhörster, H., Haase, A., Hans, N. et al. The (co-)production of arrival neighbourhoods. Processes governing housing markets in three german cities. J Hous and the Built Environ 38, 1409–1429 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-022-09995-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-022-09995-5