Abstract

Johannesburg, which is South Africa’s largest city and economic center, is still influenced by patterns of inequality of the past. Although spatial transformation has been rapid since 1994, spatial divisions along class lines are still prevalent long after the apartheid era. This is despite the fact that societal values such as inclusivity, spatial justice and equal access to resources have become the core goals of Johannesburg’s spatial and urban development. This is particularly true when addressing housing, public open spaces, transport and social infrastructure embedded in a suitable land-use mix. However, despite the adoption of numerous policies by government, this research indicates that even recent urban development projects such as Fleurhof and Waterfall are falling short in delivering those objectives. Based on a case study analysis, we show that significant dysfunctionalities become evident when evaluating these two projects, despite their meeting relevant indicators of spatial inclusion on paper. Tensions are identified between theoretical approaches and the implementation of societally relevant policy goals. These include inclusivity and spatial justice by mostly privatized provision of housing and services, and deficiencies in public maintenance of infrastructure. The research reveals, that ‘ticking-the-boxes’ behavior on policy and project level does not produce equitable, inclusive neighborhoods and urban spatial patterns, but rather reproduces spatial inequalities of the past. If these policies are to result in real spatial change and improvement in the lives of Johannesburg residents, a more proactive approach by the public sector at different levels will be necessary.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

According to UN-Habitat (2015), making human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable, as propounded by the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number 11 of the United Nations (UN) is a major developmental challenge. The SDG eleven core goals include improving access to (i) adequate, safe and affordable housing to reduce the proportion of the urban population living in slums, informal settlements or inadequate housing; (ii) an affordable and sustainable public transport system, and (iii) safe, inclusive, green and public spaces. Consequently, cities such as Johannesburg, which is regularly quoted as one of the world´s most exclusionary cities, are trying to improve access to housing and reduce inequalities (City of Johannesburg, 2016; Turok, 2018). Spatial inequalities (e.g. segregating patterns) as well as socio-economic inequalities such as income distribution, interlinked with racial differentiation, describe the city (City of Johannesburg, 2016; Everatt, 2014). Historically South Africa’s laws shaped urban design patterns by segregating residential areas for white and non-white people. The black population was located in remote townships in disfavored and marginalized locations at the city fringes (Kracker, Selzer and Heller 2010; Satgé & Watson 2018). This spatial segregation still exists in post-apartheid Johannesburg and other South African cities. The core goal in the South African Constitution (1996): "Adequate Housing for All," is translated into various legal and policy documents. These are intended to mitigate segregation patterns, promote inclusionary strategies, and establish more equitable cities.

However, the current situation continues to show ongoing spatial fragmentation along socioeconomic lines (Boyle & Michell, 2018; Todes, 2012). These segregating patterns are reinforced by the legacy of planning policies and practices which located marginalized communities in areas on the city's periphery (Cirolia & Scheba, 2019). These were far from social infrastructures, public transportation, and economic opportunities which were localized in the city center. Johannesburg's population has doubled over the past 20 years, reaching nearly five million in 2016, and is expected to continue to grow dynamically (Stats SA 2018). Domestic migration into the capital, declining household sizes (3.5–2.8) and a further increasing share of more than 50% of so called ‘low income’ households are driving the demand for affordable and inclusionary housing (Harrison et al., 2014b; Stats SA, 2011).

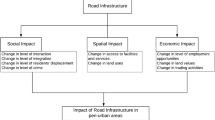

Nevertheless, despite the adoption of many policies on inclusion and affordable housing, the situation is still challenging. This points to general implementation deficiencies at various levels: (i) in the provision of social housing in sufficient numbers, and (ii) in the realization and implementation of the qualitative goals and indicators of inclusion in the "spatial reality" of urban development. The aim of our research is therefore to assess how inclusionary policies are implemented in the City of Johannesburg. This will improve our understanding of the extent to which the goals of inclusionary policies are translated into spatial reality. The two mixed-use development areas of Waterfall and Fleurhof are examined under the following parameters of spatial inclusion: (i) implementation of land use mix, (ii) provision of affordable housing (iii) access to public open spaces, (iv) social infrastructure, and (v) public transport.

2 Background

2.1 Academic discourse regarding inclusivity

Policy discourses of the global North understand the excluded as the marginalized minority whose appropriate participation is refused by the mainstream (Harrison et al., 2019). In the global South, exclusion is considered as the condition of the majority seeking to get “access to resources and benefits, that have been historically been held by the few” (Harrison et al., 2019, p. 457). Blurred boundaries between inclusion and exclusion are omnipresent, since avoiding exclusion does not always lead to inclusion (Harrison et al., 2019; SACN, 2017).

Conceptually, social inclusion and exclusion emerged in an attempt to overcome the academic and political limitations of the understanding of poverty (Aalbers, 2010; Geddes, 2000). While the debate on poverty focuses predominantly on individual and household resources, social exclusion refers to a more relational approach involving access to resources in communities and social networks (Shortall, 2008). This process-oriented conceptualization can illuminate the spatial dynamics which create disadvantages and marginalization (Beall, 2000; Preston & Rajé, 2007). Social inclusion and exclusion emerge more fully in the interplay between monetary income, access to employment opportunities, availability of housing, and accessibility of services on the one hand, and financial constraints, cultural barriers, and individual capabilities on the other. Therefore, this multi-dimensional, relational focus increases understanding concerning privileged access and participation in urban life (Sibley, 1995). In short, exclusion and inclusion are not about lacking resources but about a lack of access to these resources, especially when this lack of access prevents full participation in the economic, political, social, and cultural spheres of mainstream society (Preston & Rajé 2007; Breman, 2004).

The conceptual shift to inclusive cities is of importance for questions of urban planning and spatial justice. For instance, the absence of poverty in a city or neighbourhood does not equal social inclusion, as it might simply mean that the poor have no access to that area. However, a clear conceptual definition of social inclusion is lacking within urban scholarship, and attempts to define it often do not extend beyond the absence of social exclusion (Cameron, 2006; Preston & Rajé, 2007). The question which remains is; what should individuals and groups be included into? For example, inclusion in urban space might be satisfied when marginalised groups are able to live in the city. However, inclusion in urban planning requires some form of access to decision making structures, and influence on the development of urban space (Berger & Moritz 2018). For inclusive cities, it is thus not enough to include people in the spatial sense. Rather, people should be included in the decision, design, and implementation processes of urban politics and planning. To this end, social inclusion entails “the participation, and the ability to participate, in political and social structures” of planning (Shortall, 2008, p. 455). Thus, unpacking the concept of inclusion in the realm of urban planning reveals points of tension in its application when considering spatial justice. The most important thing is; who is included in which processes and on what conditions?

Different conceptual definitions of inclusion shape its use in urbanism. For instance, based on Preston and Rajé’s (2007) reworking of Sen’s theory of entitlement, inclusion can be topographical or relational. Topographical inclusion means that people have access to resources and opportunities close to the places they inhabit or have the opportunity to dwell in all parts of a city. Relational inclusion, on the other hand, evokes a city where resources and opportunities can be accessed by everyone without facing significant barriers. Each principle results in a different city, while a truly just city likely requires both (Harvey, 2003; Uitermark, 2009). For example, Anne Hidalgo’s idea of Paris as a 15-min city denotes topographical inclusion, as all vital functions of urban life should be available everywhere. On the contrary, Musterd et al.’s (2019) idea of neighborhoods in a city as a wardrobe resembles relational inclusion; the city consists of areas with different functions and characteristics which can still be inclusive when there is no structural exclusion from the different areas. Taking into consideration the type of inclusion to be realized shapes what urban planning is implemented. Topographical inclusion focusses on the distribution of resources and opportunities, while relational planning focusses on infrastructure, mobility and connections so that any urban inhabitant can access resources and opportunities.

Beyond conceptual challenges, there are practical challenges to planning and realizing the inclusive city (Beall, 2000). For instance, power can be distributed unequally in the translation processes from policy goals to practical implementations (Chu et al., 2018; Rebernik et al., 2018). This reinforces the idea that inclusion must be incorporated in decision-making processes (Hudson & Rönnblom, 2020; Uitermark, 2009). Furthermore, even after translation into policy goals and practices, institutional and market dynamics might hinder the implementation of inclusive city policies. For example, attempts to include less affluent households into home-ownership instead often result in higher property prices (Aalbers 2008). Policy targets for affordable housing in new developments are fought with accounting, political, and judicial strategies, as is now a well-documented occurrence around London (Crosby & Wyatt, 2019; Wainwright, 2015). Such practical hinderances to policy ideas and implementation indicate how economic, legal, and political power influence the materialization of inclusive urban policies. Overall, urban inclusion is under pressure from neoliberal urban management (Jessop, 2002; Peck, 2012). This results in reduced access of vulnerable populations to housing, work and consumption (Peck, 2012; van Lanen, 2017). Observing South African urban development through inclusive cities, however, reveals its strong historical inequalities like socio-spatial segregation, inequitable housing and service provision, and the increasing divide between rich and poor populations (SACN, 2017).

2.2 Race, class and spatial inequality

To address spatial inclusion in South Africa also requires engaging with the inequalities of apartheid. South Africa’s urban environments are characterized by spatial divisions based on race and class that are the enduring legacy of colonial and apartheid social engineering and segregationist interventions in urban development (Abrahams & Everatt, 2019). These spatial divisions translate into unequal access to housing opportunities in well-located areas of the city which could otherwise provide access to social and economic opportunities, facilities, and service delivery (Selebalo & Webster, 2017; Sobantu et al., 2019). During its implementation, apartheid manifested spatially (van Niekerk et al. 2017). This took the form where white, mostly middle- and upper-class communities were centrally located with access to formal housing opportunities, service provision, and social amenities (Heer, 2018). Simultaneously, non-white, “lower class” households predominantly resided on the urban periphery (Seekings, 2011: p.11). These were spatially and economically isolated in human settlements characterized by their informality, irregularity, and lack of basic service and infrastructure provision (Boyle & Michell, 2018; Dzikiti & Leonard, 2016). This engineered development created a social structure which was as rigid as it was self-perpetuating; one in which race was the primary determinant of class (Seekings, 2011). The housing environment reflected this reality in that the spatial inequality in resource distribution and a legislative environment limited land and property rights, while access to housing opportunities remained fundamentally unequal (Inkeri, 2019). African communities were restricted from certain urban areas, while male African workers were housed in substandard and overcrowded migrant hostels (Vosloo, 2020). With the development of informal settlements largely restricted, residential spaces for low-income African households in urban areas were mostly earmarked for high-density housing developments in planned townships on the urban periphery. During the apartheid era, neither the socio-spatial distribution of resources nor general democratic engagements, both essential for the just city, were part of urban planning (Uitermark, 2009).

However, during the post-apartheid era, commencing in 1994, the situation showed some improvement. The implementation of strategic spatial and integrated planning approaches catalyzed spatial and socio-economic transformation throughout the country. Government’s mandate in the creation of a developmental state in this regard is etched into the Constitution, with specific reference to the fulfilment of the national housing need as a basic human right (Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996). Housing played a key role in the objective to create integrated, sustainable, and resilient human settlements (National Department of Human Settlements, 2004). This was despite the presiding milieu of fragmented, and unequal urban environments, which enforced a race-based social structure. Nevertheless, a measure of progress has been made through economic reforms and empowerment programs. These have contributed to the upliftment of some previously disadvantaged households, fostering upward mobility which transcends the spatial barriers of the time (Shava, 2017). This has seen a new African middle- and upper-class move into former white neighborhoods, and has brought about a measure of racial integration to once segregated urban areas (Inkeri, 2019). New economic opportunities for previously excluded populations have thus extended their spatial inclusion, as their improved economic position has provided housing access in previously restricted urban areas.

In order to restructure the raceFootnote 1-class divisions within the City of Johannesburg, Spatial Development Frameworks were established, and ideas of compaction and integration were implemented through defined prioritized nodes and corridors for densification so as to stem urban sprawl and spatial inequalities of the past. Since 2008, as part of the SDF, the Growth and Management Strategy has included mandatory guidelines for inclusionary housing provision in areas mentioned above (Klug et al., 2013) These addressed not only the housing backlog, but also connecting infrastructure and mixed-use developments for better access to jobs and services. Further targeted interventions in the housing sector have since supported this transformation by extending spatial inclusion beyond the middle- and upper-classes. For example, the social rental housing program creates opportunities for low- to middle-income households in well-located areas earmarked for restructuring (Social Housing Regulatory Authority, 2020). Moreover, the Finance-linked Institutional Subsidy Program (FLISP) supports home ownership among households with potentially limited access to formal mortgage financing (Marais & Cloete, 2017). In addition, appropriate housing policies are being implemented in major cities in an effort to stimulate socially inclusive residential spaces (Adler & Jarallah, 2020). Related measures would require private developers to incorporate suitably affordable dwelling units in market-orientated developments, thus attracting low- to middle-income households to areas that would otherwise be inaccessible (Klug et al., 2013). This progress points toward the emergence of a more fluid social structure since the advent of democracy in South Africa, with race being less of a determinant, and urban environments increasingly characterized by their integrated neighborhoods and broader access to economic and housing opportunities (Seekings, 2011; Finchilescu & Tredoux, 2010). Landman (2010 p.16) underlined the importance of the proximity of socio-economic facilities to mixed housing projects which is not just “a mere idealistic top-down vision” but is “reflecting the bottom-up demand of many households”. This assertion is based on her survey of different medium density mixed housing developments, such as Cosmo City, a large scale urban development in the northern periphery, but close to facilities. Such integrated housing-based approaches provide a just socio-spatial distribution of resources through opportunities to live in better suited locations. However, while advantageous to those able to secure housing in such areas, without a redistribution of infrastructure and socio-economic opportunities, many peripheral areas remain excluded.

Indeed, significant challenges remain in overcoming the spatial barriers and inherent social structure created by past planning regimes. According to Seekings (2011 p. 539), factors which have contributed to the “reproduction of segregation in newly developed neighborhoods” include public housing projects being mostly located on the urban periphery due to lower cost of land. Remaining socio-economic considerations include obstacles in climbing the housing ladder, social preference, and economic considerations, contrary to transformative human settlements policy objectives. While increased fluidity in the middle- and higher-classes of the social structure is evident, particularly in relation to race and access to opportunity, the reality remains that the vast majority of low-income households are African (Schotte et al., 2017; Stats SA, 2015). In the lower echelons of the social structure, race, class, and access are invariably linked (Seekings, 2011; Turok & Visagie, 2018). This status quo manifests particularly in the urban housing conditions of low-income, predominantly African households. This is where a significant backlog in the provision of affordable housing in well-located urban areas has led to the growth of peripheral settlements on the back of continued urbanization and population growth (Abrahams & Everatt, 2019; Fieuw & Mitlin, 2018). Nevertheless, welfare programs have supported the upliftment of low-income households in addition to fully subsidized housing and in-situ upgrading interventions contributing to the alleviation of the housing need (Lemanski, 2017). Progress has been made toward achieving the developmental objectives incorporated into the Constitution and related government policies. However, significant challenges remain in overcoming the rigid social structure and the relationship between race and class as it relates to access to housing opportunities and the wider spatial context of urban environments.

2.3 The Johannesburg policy framework

Johannesburg’s policy framework on inclusivity is based on three citywide policies: (i) the Spatial Development Framework 2040 (SDF) (2016), (ii) the Inclusionary Housing Incentives, Regulations and Mechanisms (Inclusionary Housing Policy 2019), and (iii) The Nodal Review (2018) (City of Johannesburg, 2016, 2018, 2019).Footnote 2 The three policies and related instruments make use of different conceptual and instrumental components: The SDF 2040 (City of Johannesburg, 2016) for Johannesburg targets just, equitable, polycentric cities as the basis for downstream decisions. The framework is globally based on the UN-Habitat guidelines, and nationally on the National Development Plan (NDP) 2030, as well as the Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act 16 (SPLUMA 2013) (City of Johannesburg, 2016). The NDP chapter 8 sets the tone for a national blueprint on transforming human settlements and the space economy. Meanwhile SPLUMA (Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act) provides a legislative framework that is enacted upon at local level through plans such as the SDF. Consequently the SDF requires the construction of “at least 20% of affordable inclusionary housing, catering to households earning R7000 or less per month” in new developments up until the Inclusionary Housing Policy is adopted by the Council (City of Johannesburg, 2016 p. 143). Furthermore, the SDF (City of Johannesburg, 2016) aims to promote social mixing and integration of different social and economic classes and promotes a balanced provision of services (hard and soft) and the creation of opportunities for all. It promotes diversification of land use, bridging of social, spatial, and economic barriers and equitable provision of services to different neighborhoods and social groups, improved urban connectivity, and thus spatial integration are essential components of the policy.

The Nodal Review (2018) details the SDF polycentric approach. Dense, mixed-use developments in conveniently located areas, near nodes of public infrastructure are encouraged. The policy seeks to improve accessibility and proximity to jobs and economic activities and services thereby reducing urban sprawl. The Inclusionary Housing Program translates the SDF into a policy instrument. These policies are an attempt to reduce the significant backlog in housing provision and to mitigate dysfunctional housing provision for low-income households and high levels of informality (City of Johannesburg, 2019; Stats SA 2018). Nevertheless, it is acknowledged that they are not the panacea to solving the housing backlog and the dysfunctional housing provision system. Private developers are now required to construct at least 30% of new housing developments (≥ 20 units) as housing units for low- and low- to middle-income households. These developments must avoid exclusionary patterns, and therefore be located in proximity to a variety of services and employment opportunities (City of Johannesburg, 2016). The three complementary policies operationalize inclusivity and have similar aspects. They include mixed land-use, housing, public open spaces, access to public transport and social infrastructure. Thus, the aim of our study is to assess how inclusionary policies are implemented in the City of Johannesburg in order to improve understanding of the extent to which these policies are translated into spatial reality. As this research focuses on the spatial implementation of inclusion, these three policies were taken to generate relevant indicators to assess the performance of the developments.

3 Methods

The research presented in this article, follows a case study approach, combining qualitative and quantitative research methods (Fig. 1). The two cases, (i) Fleurhof and (ii) Waterfall, located in the “Consolidation Zone”, are both mixed use developments which are partially completed and are still under the planning and constructing process. Although the developments were partially under construction before the current versions of the policies, firstly, the requirements for inclusion and spatial integration already existed in formulated policies at this stage, and secondly, the developers were responsible for applying them in the further implementation of their developments. To examine two different responses to inclusion policy and its spatial translation and implementation on different scales, these private and private public partnership developments were considered. We investigated the inclusivity of the developments from a land use, housing typology, open space, social infrastructure and mobility perspective, as these indicators were measurable.

Fleurhof is an infill project located in the ‘Transformation Zone’ in the mining belt, 15 km to the Southwest of Johannesburg’s CBD (Fig. 1) next to the existing Fleurhof residential township. The region is characterized by lower incomes compared with the northern parts of the Metropolitan Region. It is a private development (CalgroM3 and others) supported by financial as well as social housing institutions in a private–public partnership with the City of Johannesburg (SACN, 2017). The land where Fleurhof is situated was bought by Calgro M3. It was financed by First National Bank and the state which applied for an Urban Development Grant to build the bulk infrastructure (Rubin and Harris 2018). Currently, only 65% of the 440 ha are developed, but when fully developed it will lodge 83,000 residents (Calgro M3, 2016, 2019b). Fleurhof is seen as an example of inclusionary housing development (Klug et al., 2013).

Waterfall is located in Midrand, halfway between Johannesburg and Pretoria (Fig. 1), and with 2200 ha it is one of the biggest private developments in South Africa. The land on which Waterfall is built is owned by the Waterfall Islamic Trust Institute and is managed by the Waterfall Investment Company (WIC) in conjunction with other private companies. The WIC installed all the bulk road infrastructure and landscaping. However, the road infrastructure was transferred to the municipality after construction, but is still maintained by the WIC (Herbert & Murray, 2015). Waterfall was built on a master plan model, where the developers followed strict design specifications for the buildings and layout. Waterfall was built as a mixed-use smart city consisting of state of the art infrastructure and privately governed structures (Murray, 2015). Compared to Fleurhof, it is less dense and consists of residents that belong to the high-income bracket.

Three data sets were gathered for this research:

-

i.

the document and policy analysis, that is building the basis for the mapping and further analysis,

-

ii.

on-site land-use and spatial mapping; and.

-

iii.

guideline based expert interviews.

The policy indicator framework was operationalized for the mapping exercise (land-use, housing, open spaces, access to public transport and social infrastructure). Data were collected between July/August 2019 and February 2020, transcribed and analyzed via CAD. Secondary data collected were spatial,- e.g. cadastral, demographic-, census- and other statistical data sets (e.g. household sizes) (City of Johannesburg, 2016; STATS SA, 2011b). Real estate prices were exemplarily mapped from a real-estate agency Private Property South Africa (Pty) Ltd. (2020) and linked to sets of statistical data. To assess the land-use mix we used the Bordoloia et al., (2013 p. 566) entropy equation:

\(Entropy = \sum\nolimits_{j} {P_{j} \times \frac{{\ln \left( {p_{j} } \right) }}{\ln \left( J \right)}}\);

Pj is “the proportion of total land area of jth land- use category found in the tract being analyzed”, J is “total land uses considered in the study area” The value lies between 0 and 1. The integer 0 stands for homogenous land use and 1 for the maximum distribution of different land uses across the selected area. Additional data and validation of material was done via six expert interviews, including two representatives of the city’s Transformation Department,, one from the Land-Use Department; two from Calgro M3 and one from Attacq(2019)a. The interviews followed the EU general data protection regulation, where the interviewees were informed about the study, and their consent was obtained. The interviews were recorded, transcribed and a qualitative content analysis performed (Gläser & Laudel, 2010).

4 Results

The following section presents the results, structured along the four main categories outlined in the policy framework: land-use mix, housing, public open space, mobility and social infrastructure.

4.1 Land use mix

The entropy index is a measure for the horizontal land-use mix, where zero represents no mixing and one, the maximum land-use mix (Bordoloia et al., 2013). Figure 2 illustrates that both Fleurhof (0.75) and Waterfall (0.73) are highly mixed developments. In both developments, 75% of the land is zoned for residential and public open space. Furthermore, the data in Fig. 2 indicate that the other land uses are similarly distributed in both cases; both developments provide a similar extent of land for economic and businesses activities. In Fleurhof, commercial areas are zoned and subdivided for small-scale economic activities. In Waterfall, on the other hand, large-scale, high-end commercial developments have been implemented, making it a center for international corporate headquarters such as PriceWaterhouseCoopers. Furthermore, Waterfall City is also a major shopping and recreational hub with the "Mall of Africa” regional shopping center that attracts shoppers and workers from the Gauteng city region.

For Fleurhof, the material suggests a mismatch between the residential area and employment opportunities as outlined in the SDF. The low share of zoned business areas and active businesses in Fleurhof indicate that most residents commute elsewhere for employment, furthermore, some informal businesses exist there. The strong focus on premium business development in Waterfall has resulted in a wide range of different job opportunities. One of the key informants (personal communication, 2019) indicated that “in the last 8 years we generated 24 000 job opportunities within Waterfall and it is estimated to produce over 80,000 job opportunities, and that employment growth and opportunities are always monitored”. Furthermore, we gleaned that contactors at Waterfall City are obliged to hire at least 30% local laborers, and Waterfall City managers are always in negotiation with local business forums to find ways of improving access to opportunities by locals in the Midrand area. Nevertheless, high-end and skilled jobs are open to everyone, while every effort is made to ensure that low skilled jobs are available to local residents.

4.2 Housing

The housing typologies in both developments are freestanding or semidetached single-family houses built on private property (Residential 1) and include multistory residential buildings of different heights on commonly used land (Residential 3). The analysis (Fig. 3) indicates that the property areas dedicated for both typologies are almost similar: In the Waterfall typology ‘Residential 1’ is slightly predominant and in Fleurhof ‘Residential 3’ is slightly predominant. The difference between both developments is the distribution and accessibility of the residential areas. In Waterfall, each housing typology is located separately in gated and access controlled estates, whereas in Fleurhof, multistory buildings mix together with single- family housing areas. Additionally, the entire development area is freely accessible except for private properties with permeable or semipermeable fences.

The level of subsidies is another distinction. At the time of the research in Waterfall (2019), there were no subsidized units available, while the data of Calgro M3 (2019b) indicate that, in Fleurhof, 3318 (29%) of the 11,322 units were fully subsidized (Fig. 2). Those units were government subsidized houses, (BNG or Breaking New Ground) units provided for households with incomes of less than R 3,500 per month and intended for ownership (GroundUP Staff, 2017). A total of 5908 (52%) units are partly subsidized, targeting the low to middle-income bracket. Partly subsidized units refer to Social Housing and GAP Housing units. Social Housing units or rental units can be subsidized by municipalities or the provincial government, focusing on households with an income between R3,500 and R7,500 per month. GAP housing is focusing on first time home-owners with an household income of more than R3,500 but less than R22,000 per month, as the households can apply for state driven FLISP (Financed Linked Individual Subsidy Program), (GroundUP Staff, 2017). Subsidized units in Fleurhof are sectional title units in multistory buildings with a size of 33–45 m2. In all, 2096 non-subsidized units, exclusively as single-family houses are built on properties of 120—575 m2, targeting the middle-income bracket.

Apartment sizes in Waterfall range from 43 to 230 m2. Single family homes are built on properties ranging from 280 to 11,000 m2 and have floor areas of 75–2685 m2. Based on prices, Table 1 shows that the housing units only serve the middle to upper income bracket, although the developer, following the Inclusionary Housing Policy, also offers smaller housing units (see table highlighted in bold). The legitimizing argument for the developers is option 3, where the policy requires that “20% of the total residential floor area must be made up of units that are 50% of the average size of market units in the same development, with a maximum of 150 m2 and a minimum of 18m2 per inclusionary unit.“ (City of Johannesburg, 2019 p. 8; developer, personal communication 2019).

The density calculations performed for each case study demonstrate that Waterfall has lower densities than Fleurhof. In the single-family residential typology, Waterfall ranges from 1 to 27 du/ha in contrast to Fleurhof 28–87 du/ha. In areas of multi-story buildings, Waterfall's density is medium at 55–91 du/ha, and Fleurhof's is high at 102–251 du/ha. Waterfall adheres to policy regarding mandated densities but does not integrate different income groups into its housing supply. On the other hand, Fleurhof meets inclusionary housing and density diversification requirements. Regarding the social mix, housing provision for the upper income bracket is not available (see also Klug et al., 2013).

4.3 Open space

The evaluation (Fig. 4) is based on the cadastral data (City of Johannesburg, 2015); the masterplans of the developers (Attacq, 2019; Calgro M3, 2019a); and own land use mapping on site. It illustrates that in Fleurhof the requirements are met with 51% public environment,(i.e. public open space including streets, of the total development area), and 35% public open space accessible to almost every resident within 500 m. The municipality is responsible for the maintenance of the public open space there. In Waterfall, the available open space, of 16%, is barely sufficient to comply with the policy indicators, but more essentially, it is completely privatized with the exception of the feeder roads belonging to the Johannesburg Roads Authority.

Within the analysis it was possible to identify a clear difference between the qualities of open space in the two developments of Fleurhof and Waterfall, which should have been avoided according to the policies. To better understand the functionality of the open spaces, a distinction was made between active open space (e.g.: designated playgrounds, sports fields) and passive open space (e.g.: wetland areas) in both cases. In Fleurhof, the zoned public open space is undeveloped and dysfunctional or not maintained. According to the interview data, the wetland area cannot be developed due to its ecological sensitivity and is prone to crime. In addition, the dedicated sports field, urban agricultural area, or servitude areas designed as parks are littered, unfurnished, and cannot be used appropriately by residents (see pictures in Fig. 4). In Waterfall, however, the developer builds and maintains well-equipped playgrounds, sports fields, and pools within the estates, as well as bike and walking paths along the wetlands. Access remains off-limits to the public and is restricted to residents and their visitors. Through exclusion and control, the developer enhances the safety and quality of life for Waterfall residents and the amenities of their development.

4.4 Social infrastructure

The land use analysis illustrates that 15% of the land in Fleurhof is dedicated for community services and social infrastructure such as educational and health care facilities as well as for institutional purposes. In Waterfall, the designated social infrastructure and amusement facilities account for 3% of the total land area, while the main institutional purpose is the ‘Waterval Islamic Institute’ with 9% of the total land. This means that in relation to the total area, Waterfall with 2% provides much less basic social infrastructure than Fleurhof with 10%. Nevertheless, the on-site analysis revealed that the implementation of social infrastructure has been better in Waterfall, precisely because everything is privatized. There are educational facilities ranging from kindergartens to universities and a hospital, as well as commercial entertainment facilities such as social halls within estates for residents. There are also other facilities at retail nodes which are open to the general public, albeit under the rules of the owners.

In Fleurhof, on the other hand, two schools, one private and one public, and smaller formal and informal day care centers have been built to date. Clinics, a high school, and facilities for institutional and community purposes are planned for areas but have not been implemented. The reason, according to interviews with developers, is the lack of funding or commitment from the City of Johannesburg or government agencies, which hampers the successful implementation of public facilities.

It also became apparent from the policy analysis that their indicators relate to the spatial accessibility of social infrastructure, but not its affordability. Consistent with this, the developer of Waterfall has placed social infrastructure along feeder roads near public transportation and economic nodes (Figs. 5 and 6), while the designated sites in Fleurhof are scattered throughout the development.

4.5 Transport

In the Fleurhof and Waterfall developments, the accessibility to public transport within indicated distances is portrayed in Fig. 6. However, means of transportation in both areas are limited to private mobile transport (cars), paratransit such as minibus taxis, or walking, thus indicating a low level of multimodality. According to the statistics (Simpson et al. 2019) and key informants, minibuses are one of the primary means of transportation for the low income bracket, nevertheless they are privately operated, do not have fixed routes or schedules and therefore were not analyzed. A feeder bus line 'F6' is the only public transport in Fleurhof and connects Fleurhof with Industria West, 8 km to the northwest of the development. In Waterfall two ‘Gautrain’ bus lines are implemented, connecting the development and the ‘Gautrain’ train station in Midrand. The 'Gautrain', a limited light rail system targeting middle income commuters, extends along the north–south axis, connecting key nodes such as Midrand, Sandton and the Johannesburg CBD, with Pretoria (Harrison et al., 2014a). In order to increase public transport services and the attractiveness of the development, an additional Gautrain station is intended by the developer in Waterfall.

Furthermore, a 'Metrobus' line was implemented to connect Midrand with the Johannesburg CBD at low frequencies. To provide access to public transport or other services, there are bicycle lanes within the residential estates and along the Mall of Africa in Waterfall (Fig. 6/3). However, these are not available in Fleurhof. The on-site analysis indicated that walkability is supported by design conformity of pedestrian walkways along main streets and active frontages with mid-height walls or permeable fences throughout the Fleurhof area. The security of residents on the street is potentially improved by this open design and 'eyes on the streets' principle. Furthermore, it is supported by an active community, according to interview data. Nevertheless, the walkability is limited by a non-continuous network of paths, due to the missing sidewalks in side streets (see Fig. 6/2) in combination with a lack of maintenance (see Fig. 6/1). By contrast, the developer of Waterfall attaches great importance to the external appearance of the streets with regard to the aesthetic quality of street furniture and vegetation. Regarding aspects of security on the streets, access controls, patrols by security guards, cameras and emergency buttons are available along the streets.

5 Discussion

Inclusivity in the housing sector is expected to provide equal access to adequate housing for all, according to the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996). The two developments illustrate different and arbitrary approaches to implementing spatial inclusion. On the one hand the developers of Fleurhof comply with SDF policy goals by providing housing units for the low-to-middle income households in medium to high density areas. They are addressing the existing housing backlog significantly in the supply of 81% of fully or partially subsidized housing units. On the other hand, Waterfall, as an upmarket residential development with low density, homogenous enclaves, also offers small-scale housing units of approximately 40 m2. According to the developer, these units are considered "inclusionary" units. This is also justified by the Inclusionary Housing Policy option 3, which declares that units must be 50% of the average market unit size to be inclusive and accessible for households that “may not otherwise afford to live in those developments” (City of Johannesburg, 2019, p. 2). Nevertheless, the units remain unaffordable for low-income groups.

In this case, the original intent of the policy delivering housing opportunities for the low to middle income is violated, as the Inclusionary Housing Policy contradicts the SDF in its definition of inclusionary housing. Developers are using loopholes of definition in the applied policy framework to legitimize upscale real estate developments and align them with inclusive housing policy goals, while actual access to housing and spatial resources appears to be limited to high-income groups. Moreover, interview data confirmed that developers are not only exploiting this policy gap, but deliberately initiated it in the policy draft negotiation processes by calling for alternative options rather than simply providing housing for the low—to middle-income homeowners at affordable housing costs. This has led to the change in the definition of inclusionary housing, and as mentioned earlier, and to additional options which allow for smaller housing units to be provided than would otherwise be the case (Transformation Department 1, personal communication 2019).

Aligning with. van Lanen (2017), (Peck (2012), Williams et al. (2007) the case shows that privatized service and housing delivery might discriminate against social and inclusionary concerns and societal goals in favor of financial returns. Ethical tensions are actively circumvented by lobbying the political process and acting symbolically to establish a ‘moral minimum’ in place of equal access to spatial resources and adequate housing. In Waterfall, housing accessibility is significantly influenced by affordability. Thus, contrary to developers' promises—to integrate different ethnic groups—the barriers seem to be “no longer racial, but financial” (Murray, 2011). The majority of Black South Africans belong to the low income bracket, thus the development remains inaccessible in terms of race and income and perpetuates the spatial segregation of the past (Schotte et al., 2017; Stats SA, 2015),. Nevertheless residents of Waterfall are able to follow the tendencies of racial integration mentioned by Inkeri (2019), where the black upper and middle class is able to move into the wealthy, former white suburbs of the city.

In addition, our research aligns with previous work from Herbert & Murray (2015), who point to conformity-driven "tick-the-box" behavior by developers. Through this process, they ensure a smooth permitting process by adhering to minimum standards of inclusivity in terms of "inclusionary" housing, land use mix, proximity to public transport or social infrastructure, and provision of public open space. The spatial analysis confirmed that policy standards are followed according to developers plans, but in reality the areas show significant dysfunctionalities and inequalities.

Mobility provision is still strongly focused on automobiles; and while public transport is accessible within 2 km (beeline) from the developments, the actual accessibility and usability in practice is problematic. In both cases affordable transport, such as minibuses is informal without a schedule, while high-scale mobility services (e.g. Gautrain: high-speed commuter train service) are too expensive for low-middle income households (Harrison et al., 2014a). Poor connections of bus or railway stations within the developments as well as car-centered road designs are promoting commuting by bicycle and/or walking as well as multimodal travel behavior.

Similarities emerge for the provision and accessibility of social infrastructure and public open spaces. The research shows three different patterns of spatial resources (land-use/zoned plots): i) zoned but not implemented (not developed/built up), such as the social infrastructure and businesses in Fleurhof, ii) zoned and implemented, but poorly maintained, such as public open spaces in Fleurhof or iii) implemented, privatized and fully commercialized such as the open spaces and social infrastructure in Waterfall.

The mix of zoned land use on paper in Fleurhof, in conjunction with limited or missing developments on site results in an inability to meet the local conditions and needs of residents. This is reflected in the informal economic activity that actually occurs and behavior patterns of commuting residents.

The Fleurhof-case illustrates the increased importance and pressure on public open spaces. Since the community infrastructure is only poorly developed, the apartments are small, the only space for the community to meet, exchange, establish relationships and participate in public are the open spaces. The poor design quality (e.g. missing furniture), lack of care and regular maintenance leads to littering, reduced usability and accessibility and the local perception that those places are unsafe. In Waterfall, on the other hand, well designed and maintained privatized open spaces were established. Here privatization and commercialization create privileged access to open spaces and amenities that are imitating public life and ‘the urban’ (Sibley, 1995).

Finally, the analysis shows that in both developments, spatial patterns of exclusion are perpetuated in reality; social inclusion in the distribution of and access to spatial resources remain limited. Planning officials acknowledge developer’s ability to create inclusive designs on paper, but in reality exclusive development comes about because of the new many implementing agencies, where policy congruency is lost. For example, one planner notes “Planning and policy theories are good but if it comes to implementation you’ve got separate departments that deals with different topics”. Furthermore, planners noted that, although policy stipulates guidelines on inclusivity, they often do not follow up to ensure that what is in the approved plans is being carried out on development sites. One also has to take cognizance of the layers of inclusivity and note that developments focus on housing provision which normally is the municipalities’ responsibility, and it is easy to monitor the size of units provided. Other aspects of inclusivity such as provision and access to education and transport provision are difficult to monitor, given that the responsibilities lie beyond the municipality to provincial and national government. There is a sense of resignation from municipal officials that, while it is ideal to promote inclusivity, the municipality has no resources to provide other social amenities and infrastructure to ensure inclusive developments. As a result of the lack of financial capacity, there were intensive negotiations between the Waterfall as well as Fleurhof property developers which resulted in the municipality having to make concessions (Murray, 2015; Rubin & Harris 2018). Property developers know that if they can finance bulk infrastructure such as roads the approval process is often fast-tracked. In Waterfall, the developer took large scale bulk infrastructural investments to facilitate the planning process and zoning regulations (Herbert & Murray, 2015). In Fleurhof, a PPP with the City played an important part in the negotiations for the final spatial layout and building typologies. In this case the developer acted as the planner and constructor, but afterwards the properties and buildings are transferred to institutions like JOSHCO, or MHA, private owners, or the City (Rubin & Harris 2018). The City seems to have had a greater proactive involvement, which may have led to better implementation of inclusivity, while Waterfall operates more like a ‘self-governing enclave’ with its own regulations, aesthetic principles, or security systems (Murray 2015 p. 506).

Approved megaprojects, such as Waterfall in the northern, wealthy part of the city, lead to a further discontinuity in the urban landscape, where infrastructure is selectively inclusive and only for the affluent (Wippel, 2018). Fleurhof is the desired infill project in the transformation zone of the Mining Belt. However, it follows the tendencies described by Beall (2000), where the urban poor continue to be located in marginalized areas with high population density and poor infrastructure, requiring long commutes to work.

In the context of the global South, the process of exclusion is continuing, where the majority are seeking to obtain “access to resources and benefits, that have historically been held by a few” (Harrison et al., 2019, p. 457). The socio spatial distribution of resources as an important element of the just city therefore remains a theoretical vision, while the interests of the private market are favored (Uitermark, 2009).

Thus, the current format of increasingly privatized urban housing developments and their provision of urban services are not meeting the policy goals of inclusivity or the constitutional promise of adequate housing for all. The findings suggest that the establishment of public–private partnerships and the increasing privatization of public service delivery and urban management have led to a laissez-faire position by public departments. The expectation is that the invisible hand of the market will provide what developers' plans promise and public policy expects. Due to the lack of financial capacity, the public sector is also dependent on private developers, and facilitates their approval procedures or makes major concessions in the formulation of policy programs in their favor (Transformation Department 1, personal communication 2019).

New questions that can emerge relate to how we can move from prescriptive inclusionary policies which stifle local development to clearly assign responsible organs for implementation. Thus, further studies can look at the vertical policy coordination, where policy at national, provincial and municipal level as well as sectoral interests are examined and how they influence urban development.

6 Conclusion

The South African government has enacted a number of policies to promote inclusion and provide more access to urban resources. While the current alignment of policies at the citywide level is promising and ambitious, their implementation in the built environment points to notable shortcomings.

Firstly, we were able to show, that the current policy approach results in a ‘ticking-the-boxes’ response from the developers; meeting the target on paper and on the plan does not result in equitable, inclusive neighborhoods. This does not trigger policy performance and thus deliver a just access to social, economic and political life for Johannesburg citizens. It is safe to assume that the power from the public sector towards private developers is less, than the developer’s power in their daily practices themselves. This is based on their financial and economic power and ambiguous policy goals and a lack of monitoring. The adjustment of policies in favor of developers, as well as the facilitation of approval procedures due to the construction of infrastructural facilities indicate that private and speculative interests continue to shape urban development in Johannesburg. Spatial and economic inequalities from the past are reproduced, as low-income households continue to be located in high-density areas with poor infrastructural access. High-income households continue to reside in safe, well-equipped gated estates surrounded by urban amenities.

Therefore, the research confirms the perpetuation of segregating and exclusionary patterns due to the unequal access to social services, and a concentration of economic power in these new project developments (Ballard et al., 2017; Murray, 2011; Todes, 2012; Turok, 2018). Hence, the success of overcoming spatial barriers and meeting the goal to provide adequate, inclusive housing for 50% of the black African, low-income households is questionable at this point. The favorable policies are currently not leading to the implementation of a more inclusive spatial reality for the residents of the City of Johannesburg.

If these policies are to result in a spatial change and thus improvement in the lives of Johannesburg residents, a more vigorous approach by the public sector at different levels will be necessary. On the one hand, consistent objectives are essential for different departments of the municipality, as well as at the regional and national level in order to avoid loopholes for the developers. On the other hand, these must enable monitoring after the approval process. An increase in public financial capacities for (social) infrastructural connections and affordable housing, e.g. through subsidies, could also reduce political dependencies towards developers.

Data availability

The article was established in conjunction with the Master Thesis of Edith Hofer with the title “Insight into Inclusivity from a Comparative Case Study Regarding Two Urban Development Projects in Johannesburg.” The datasets generated during the current study are available in the library of the University of Applied Sciences repository, https://www.fh-salzburg.ac.at/services/bibliotheken.

Notes

Within this research, the term „race “ or „racial “ reflects the historically emerged patterns of racial disparities which still exist in South Africa, but do not point out that these circumstances are tolerated.

At the time of the research the Nodal Review was not approved. Therefore the documents, called Nodal Review Policy 2018/19 were taken for the analysis. In February 2020 the council approved the policy, which is now called Nodal Review Policy 2019/20. Fleurhof and Waterfall developments commenced before the Inclusionary Housing Policy was put in place.

References

Aalbers, M. B. (2010). Social exclusion. In R. Hutchison (Ed.), Encyclopedia of urban studies (1st ed., pp. 731–735). SAGE Publications.

Abrahams, C., & Everatt, D. (2019). City profile: Johannesburg, South Africa. Environment and Urbanization ASIA, 10, 255–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0975425319859123

Adler I., Jarallah A.-M. (2020). Inclusionary housing: An analysis of a potential affordable housing tool in Cape Town, South Africa. Degree Project, Sweden Royal Institute of Technology.

Attacq (2019). Waterfall Masterplan. Retrieve 4 May from https://www.attacq-report.co.za/ir-2018/manufactured-resources.php.

Ballard, R., Dittgen, R., Harrison, P., & Todes, A. (2017). Megaprojects and urban visions: Johannesburg’s Corridors of Freedom and Modderfontein. Transformation, 95, 111–139. https://doi.org/10.1353/trn.2017.0024

Beall, J. (2000). From the culture of poverty to inclusive cities: Re-framing urban policy and politics. Journal of International Development, 12, 843–856. https://doi.org/10.1002/1099-1328(200008)12:6%3c843:AID-JID713%3e3.0.CO;2-G

Berger, M. (Mathieu) & Moritz, B. (Benoit) (2018). Experiencing trans disciplinarity through urban policy research. In: Berger, M. (Mathieu), Moritz, B. (Benoit), Carlier, L. (Louise), Ranzato, M. (Marco) (eds): Designing Urban Inclusion: Metrolab Brussels Masterclass I. Brussels: Metrolab.Brussels.

Bordoloia, R., Mote, A., Pratim, P. S. & Mallikarjuna, C. (2013). Quantification of Land Use diversity in the context of mixed land use (No. 104). Procedia- Social Behaviorial Sciences. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1877042813045412/pdf?md5=1e01ad9890836e0664a4bd5c9f79b10a&pid=1-s2.0-S1877042813045412-main.pdf.

Boyle, L., & Michell, K. (2018). A Management Concept for Driving Sustainability in Marginalised Communities in South Africa. Urban Forum, 29, 185–204. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12132-017-9329-9

Breman, J. (2004). Social exclusion in the context of globalization. International Labour Organization. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.908164

Calgro M3 (2016). Fleurhof. Retrieved from https://www.calgrom3.com/index.php/fleurhof.

Calgro M3 (2019a). Fleurhof Development: geographic data. Accessed August 2019.

Calgro M3 (2019b). Fleurhof-erf information and unit calc: calculations. Accessed August 2019.

Cameron, A. (2006). Geographies of welfare and exclusion: Social inclusion and exception. Progress in Human Geography, 30, 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132506ph614pr

Chu, E., Schenk, T., & Patterson, J. (2018). The dilemmas of citizen inclusion in urban planning and governance to enable a 1.5 °C climate change scenario. Urban Planning, 3(2), 128–140. https://doi.org/10.17645/up.v3i2.1292

City of Johannesburg (2015). Cadastral data. Accessed August 2019.

City of Johannesburg (2016). SDF 2040: Spatial Development Framework 2040. Retrieved 6 July from http://bit.ly/joburg-sdf-16.

City of Johannesburg (2019). Inclusionary Housing Incentives, Regulations and Mechanisms: Inclusionary Housing. Retrieved from https://www.joburg.org.za/documents_/Pages/Key%20Documents/policies/Development%20Plan-ning%20%ef%bc%86%20Urban%20Management/Citywide%20Spatial%20Policies/City-Wide-Spa-tial-Policies.aspx.

City of Johannesburg (2018). Nodal Review: Nodal Review for Council Consideration 2018/19 City of Johannesburg. Retrieved 8 July from https://www.joburg.org.za/docu-ments_/Pages/Key%20Documents/policies/Draft-nodal-review-Policy.aspx.

Cirolia, L. R., & Scheba, S. (2019). Towards a multi-scalar reading of informality in Delft, South Africa: Weaving the ‘everyday’ with wider structural tracings. Urban Studies, 56, 594–611. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098017753326

Constitution of the Republic of South Africa (1996). Republic of South Africa, Act 108 Chapter 2: Bill of Rights.

Crosby, N., & Wyatt, P. (2019). What is a ‘competitive return’ to a landowner? Parkhurst Road and the new UK planning policy environment. Journal of Property Research, 36(4), 367–386. https://doi.org/10.1080/09599916.2019.1690028.

Dzikiti, L.G. and Leonard, L. (2016). Barriers towards African youth participation in domestic tourism in post-apartheid South Africa: The case of Alexandra Township, Johannesburg. African Journal of Hospitality, Tourism and Leisure:1–17.

Ellipse Waterfall (2020). https://ellipsewaterfall.co.za/. Accessed 25 March 2020.

Everatt, D. (2014). Poverty and inequality in the Gauteng city-region. In P. Harrison, G. Gotz, A. Todes, & C. Wray (Eds.), Changing space, changing city. Wits University Press.

Fieuw, W., & Mitlin, D. (2018). What the experiences of South Africa’s mass housing programme teach us about the contribution of civil society to policy and programme reform. Environment and Urbanization, 30, 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247817735768

Finchilescu, G., & Tredoux, C. (2010). The changing landscape of intergroup relations in South Africa. Journal of Social Issues, 66, 223–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01642.x

Geddes, M. (2000). Tackling social exclusion in the European union? The limits to the new orthodoxy of local partnership. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24, 782–800. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00278

Gläser, J., Laudel, G. (2010). Experteninterviews und qualitative Inhaltsanalyse als Instrumente rekonstruierender Untersuchungen. 4. Auflage. VS Verlag Wiesbaden.

GroundUP Staff (2017). Everything you need to know about government housing. Retrieved 27 Dec from https://www.groundup.org.za/article/everything-you-need-know-about-government-housing/.

Harrison, P., Gotz, G., Todes, A., & Wray, C. (Eds.). (2014a). Changing space. Wits University Press.

Harrison, P., Gotz, G., Todes, A., & Wray, C. (2014b). Materialities, subjectivities and spatial transformation in Johannesburg. In P. Harrison, G. Gotz, A. Todes, & C. Wray (Eds.), Changing space (pp. 2–39). Wits University Press.

Harrison, P., Rubin, M., Appelbaum, A., & Dittgen, R. (2019). Corridors of freedom: Analyzing Johannesburg’s ambitious inclusionary transit-oriented development. Journal of Planning Education and Research, 39, 456–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X19870312

Harvey, D. (2003). The right to the city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 27, 939–941. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0309-1317.2003.00492.x

Heer, B. (2018). Propertied Citizenship in a Township and Suburb in Johannesburg. In L. Kroeker, D. O’Kane, & T. Scharrer (Eds.), Middle Classes in Africa: Changing Lives and Conceptual Challenges (pp. 179–201). Springer International Publishing.

Herbert, C. W., & Murray, M. J. (2015). Building from scratch: new cities, privatized urbanism and the spatial restructuring of Johannesburg after Apartheid. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39, 471–494. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12180

Hudson, C., & Rönnblom, M. (2020). Is an ‘other’ city possible? Using feminist utopias in creating a more inclusive vision of the future city. Futures, 121, 102583. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.futures.2020.102583

Inkeri, R. (2019). “Race” Conditioning Social Cohesion in the Post-Apartheid Cape Town Neighbourhood. PhD Dissertation, University of Helsinki.

Jessop, B. (2002). Liberalism, neoliberalism, and urban governance: A state-theoretical perspective. Antipode, 34, 452–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00250

Klug, N., Rubin, M., & Todes, A. (2013). Inclusionary housing policy: A tool for re-shaping South Africa’s spatial legacy? Housing and the Built Environment, 28, 667–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-013-9351-814

KrackerSelzer, A., & Heller, P. (2010). The spatial dynamics of middle-class formation in post apartheid South Africa: enclavization and fragmentation in Johannesburg. In J. Go (Ed.), Political power and social theory. Emerald.

Landman, K. (2010). A home close to opportunities in South Africa: Top down vision or bottom up demand? South African Journal of Town and Regional Planning, 56, 8–17.

Lemanski, C. (2017). Citizens in the middle class: The interstitial policy spaces of South Africa’s housing gap. Geoforum, 79, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.12.011

Marais, L., & Cloete, J. (2017). Housing policy and private sector housing finance: Policy intent and market directions in South Africa. Habitat International, 61, 22–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2017.01.004

Murray, M. J. (2011). City of extremes: The spatial policies of Johannesburg. Duke University Brand.

National Department of Human Settlements (2004). A comprehensive plan for the development of integrated sustainable human settlements. Retrieved 19 Aug from http://www.dhs.gov.za/sites/default/files/documents/26082014_BNG2004.pdf.

Musterd, S., Damhuis, R., Hochstenbach, C., et al. (2019). De Regio Als Garderobe: Houshoudens, Levensfasen En Woonmilieus in de Nederlandse Metropool. Amsterdam University Press.

Peck, J. (2012). Austerity urbanism: American cities under extreme economy. City: Analysis of Urban Trends Culture, Theory, Policy, Action, 16, 626–655. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604813.2012.734071

Preston, J., & Rajé, F. (2007). Accessibility, mobility and transport-related social exclusion. Journal of Transport Geography, 15, 151–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtrangeo.2006.05.002

Private Property South Africa (Pty) Ltd. (2020). Retrieved 22 Feb from https://www.privateproperty.co.za/.

Rebernik, N., GoličnikMarušić, B., Bahillo, A., et al. (2018). (2019) A 4-dimensional model and combined methodological approach to inclusive Urban planning and design for ALL. Sustainable Cities and Society, 44, 195–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scs.2018.10.001

Rubin, M., & Harris, R. (2018). 11. An effective public partnership for suburban land development: Fleurhof, Johannesburg. In R. Harris & U. Lehrer (Eds.), Global Suburbanisms. The Suburban Land Question: A Global Survey (pp. 258–279). Toronto: University of Toronto Press. https://doi.org/10.3138/9781442620629-015

SACN (2017). The Urban Land Paper Series Volume 2 A Transit-Oriented Development Lens. Johannesburg.

Satgé, R., & de, Watson V. (2018). African cities: Planning ambitions and planning realities. In R. de Satgé & V. Watson (Eds.), Urban planning in the global south: Conflicting rationalities in contested urban space (Vol. 27, pp. 35–61). Springer International Publishing.

Schotte, S., Zizzamia, R., Leibbrandt, M. (2017). Social stratification, life chances and vulnerability to poverty in South Africa. 208.

Seekings, J. (2011). Race, class, and inequality in the South African City. In G. Bridge & S. Watson (Eds.), The new Blackwell companion to the city. Wiley-Blackwell.

Selebalo, H., Webster, D. (2017). Monitoring the right of access to adequate housing in South Africa, Johannesburg. Studies in Poverty and Inequality Institute.

Shava, E. (2017). Black economic empowerment in South Africa: Challenges and prospects. JEBS, 8, 161–170.

Shortall, S. (2008). Are rural development programmes socially inclusive? Social inclusion, civic engagement, participation, and social capital: Exploring the differences. Journal of Rural Studies, 24, 450–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2008.01.001

Sibley, D. (1995). Geographies of exclusion: Society and difference in the West. Routledge.

Simpson, Z., McKay, T., Patel, N., Sithole, A., van den Berg, R., & Chipp, K. (2019). Past and Present Travel Patterns in the Gauteng City-Region. Retrieved 2 Dec 2019, from http://www.uj.ac.za.

Sobantu, M., Zulu, N., & Maphosa, N. (2019). Housing as a basic human right: A reflection on South Africa. SAJSWSD, 31, 1–18.

Social Housing Regulatory Authority (2020). Who we are and what we do. Retrieved 19 Aug from http://shra.org.za/node/9.

South African Government (2013). Spatial Planning and Land Use Management Act, Act No16 of 2013, N° 36730; Government Gazette 38828. https://www.gov.za/documents/spatial-planning-and-land-use-management-act

Stats SA (2011) Statistics by place- City of Johannesburg. Retrieved 1 Aug from http://www.statssa.gov.za.

Stats SA (2015). Census 2011: Income dynamics and poverty status of households in South Africa. Report number 03–10–10. Pretoria. Retrieved 1 Dec from www.statssa.gov.za.

Stats SA (2018). Provincial profile: Gauteng: Community Survey 2016. Report number 03–01–09. Pretoria. Retrieved 1 Dec from http://www.statssa.gov.za.

Todes, A. (2012). Urban growth and strategic spatial planning in Johannesburg, South Africa. Cities, 29, 158–165.

Turok, I. (2018). Worlds apart: Spatial inequalities in South Africa. In M. N. Smith (Ed.), Confronting inequality: The South African crisis. Fanele.

Turok, I., Visagie, J. (2018). Inclusive urban development in South Africa: What does it mean and how can it be measured? Working Paper. Retrieved from https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/handle/20.500.12413/13770.

UN-Habitat (2015). Sustainable Development Goal 11: Make cities and human settlements inclusive, safe, resilient and sustainable. A Guide to Assist National and Local Governments to Monitor and Report on SDG Goal 11 + Indicators Monitoring Framework - Definitions - Metadata - UN-Habitat Technical Support. Retrieved from https://unhabitat.org/sdg-goal-11-monitoring-framework/.

Uitermark, J. (2009). An in memoriam for the just city of Amsterdam. City, 13, 347–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/13604810902982813

van Lanen, S. (2017). Living austerity urbanism: Space–time expansion and deepening socio-spatial inequalities for disadvantaged urban youth in Ireland. Urban Geography, 38, 1603–1613. https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1349989.

van , T.J.B., Viviers, J., Cilliers, E.J. (2017). Corridor densification option as a means for restructuring South African cities. In: 19th Conference on Municipal Infrastructure and Road, pp 4–5.

Vosloo, C. (2020). Extreme apartheid: The South African system of migrant labour and its hostels. IT. https://doi.org/10.17159/2617-3255/2020/n34a1.

Wainwright, O. (2015) Revealed: How developers exploit flawed planning systems to minimise affordable housing. The Guardian.

Williams, P., Gill, A., & Ponsford, I. (2007). Corporate social responsibility at tourism destinations: Toward a social license to operate. Tourism Review International, 11, 133–144. https://doi.org/10.3727/154427207783948883.

Wippel, S. (2018). Stadtentwicklung in Tanger: Rekonfigurationen des Urbanem im neoliberalen Kontext. In: Al-Hamarneh A, Margraff , Scharfenort N (eds) Neoliberale Urbanisierung: Stadtentwicklungsprozesse in der arabischen Welt. transcript, Bielefeld, pp 33–73.

Funding

Open access funding provided by FH Salzburg - University of Applied Sciences. The project is funded by the OEAD S&T Cooperation Program (ZA11/2019), The National Research Foundation, South Africa (Grant No 116064), and a Master Thesis Scholarship provided by the University of Applied Sciences Salzburg.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hofer, E., Musakwa, W., van Lanen, S. et al. Inclusivity insights: two urban development projects in Johannesburg. J Hous and the Built Environ 37, 1835–1858 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09916-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-021-09916-y