Abstract

In the past decade, Public Rental Housing (PRH) has become the program of providing affordable rental housing to low- and middle-income households in China. Even though descriptions of the governance results are numerous, the previous studies are not underpinned by a theoretical foundation from a governance perspective, nor have they empirically examined whether PRH governance works on the ground. This explorative and empirical paper aims to fill this gap of an outcome-oriented evaluation of the impacts of governance as perceived by the final user. Central government formulated the objective for PRH governance as maintaining stability in the society. Whether the tenants perceive the goal of social stability as achieved was measured along three governance outcome dimensions: satisfaction with housing quality, satisfaction with housing quantity, and willingness to communicate with the government about PRH governance. Data were collected from questionnaires to PRH-tenants in Chongqing, the most important pilot city of PRH provision in China. The findings show that the perceived governance outcomes were quite mixed as tenants were moderately satisfied with PRH housing quantity, but less satisfied with housing quality, and thought they could relatively easily communicate with local government. In view of these mixed outcomes, to strengthen the effectiveness of PRH governance in the eyes of the tenants, this study suggests local governments: (1) to rethink and redevelop the performance evaluation; (2) to rethink the relations with non-governmental actors and organise a monitoring system that will assist in optimizing housing quality; and (3) to facilitate tenants’ communication with local government.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Public Rental Housing (PRH) has become an important program of rental housing provision at regulated rents to low-and middle-income households in urban China since 2010. The central government sets policies and mandates for the whole country’s PRH provision, while local governments are in charge of the local policy formulation and implementation (Zhou & Ronald, 2017a). Central government only provide a small proportion of funds needed for the realization of PRH provision. As local governments turn to non-governmental actors for finance (Zou, 2014), the governance of PRH has changed profoundly in the last decade (Ministry of Finance [MoF], 2015; Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development [MOHURD], 2018; Shi et al., 2016).

One decade of PRH governance development has achieved mixed results. The official data show that 37 million people lived in PRH by the end of 2018 (MOHURD [2019] No.55). At local level, cities, especially first- and second- tier cities with severe housing affordability problems, have put a lot of efforts in PRH provision (Jiefang Daily, 2017; Xinhua net, 2018). Nevertheless, scholars argue that the involved non-governmental actors do not find their role attractive, which can lead to unsustainable development of the governance (see for example, Huang, 2015; Lin, 2018).

In order to see if it is efficient, scholarly attention has been widely focused on the changes of PRH governance and the institutions that are involved as well as the resulting challenges (Deng, 2018; Lin, 2018; Zhang et al., 2018; Zhou & Ronald, 2017a). However, the existing studies on Chinese PRH fail to measure PRH governance from two aspects. First, these studies are not underpinned by a theoretical foundation from a governance perspective. Since the governance of PRH now has become more complex than before as local governments cooperate with non-governmental actors, the measurement based on governance outcomes is important. Secondly, the previous studies have not empirically examined whether PRH governance works on the ground. This paper aims to close these knowledge gaps.

To measure governance is a precondition for its improvement (Bovaird & Löffler, 2003; Heinrich, 2002; Rauschmayer et al., 2009). Hertting and Vedung (2012, p. 38) indicate the rationale of governance evaluation as “to create repositories of descriptive and judgmental insights for reasoned practical thought and action”. Based on the performance results, public officials and stakeholders will be able to adapt (improve) governance based on evidence. Studies about governance measurement are abundant. This paper follows the approach proposed by scholars such as Freyburg et al. (2009), Anten (2009), and Ehler (2003) to determine that effectiveness of governance means to analyse whether the objective of governance is fulfilled by measuring the outcomes perceived by final users (see Sect. 2 for the justification). This is the so-called outcome-oriented approach which allows to show the effectiveness of the governance (Heinrich, 2002).

Since the objective of Chinese PRH governance is to maintain social stability (prevent social unrest; see Sect. 2 for details), tenants’ perceptions about the outcomes of PRH governance are taken here to measure the effectiveness of PRH governance. This paper thus investigates: does PRH work in terms of the effectiveness of its governance from the perspective of tenants?

To answer the research question, data were collected from PRH-tenants by questionnaires in Chongqing, which is the most important pilot city of PRH provision in China (see justification of selection Chongqing as case study in Sect. 3). A literature review is also applied as research method in this paper. The review consists of a study of scientific literature as well as policy documents and government reports relevant to the practice of PRH governance in China and in Chongqing. Interviews from our other works on PRH governance in Chongqing are also adopted in this paper as literature to provide background information about PRH governance and build a comprehensive understanding of tenants’ perceptions towards PRH.

To contextualise the answer to the research question, Sect. 2 summarises the literature about the outcome-oriented approach for governance evaluation and presents a brief introduction of the PRH governance in China and in Chongqing. Section 3 introduces case selection and the methods for data collection and analysis. Subsequently, we present the findings, the discussion and finally, the conclusion and the policy implications.

2 Literature review

2.1 Governance and its evaluation

The term ‘Governance’ originated from Latin, meaning ‘to rule or to steer’ (Ismail, 2010). The concept has been studied extensively in the field of welfare systems in recent decades. Examples include Rhodes (1996), Peters and Pierre (1998), Bevir et al. (2003), Kooiman (2003), Mayntz (2003), Stoker (1998). From their perspectives, the term ‘governance’ is a mode, or a structure of steering based on, but also going beyond, the government to make and implement decisions. PRH governance is therefore interpreted as a structure –PRH network– of a wide range of government and non-governmental actors that act in all its phases of PRH provision from policy design to implementation and realisation.

To precisely measure governance is difficult and “there are no silver bullets in measuring governance” (Kaufmann & Kraay, 2007, p. 3). Scholars discuss the importance of the measurement (Buduru & Pal, 2010), the various definitions of ‘good governance’ (Patton & Director, 2008; Rotberg, 2014), the difficulties that may be encountered when measuring governance (Haarich, 2018; Kaufmann & Kraay, 2007), and approaches to measure governance (Anten, 2009; Ehler, 2003; Rauschmayer et al., 2009).

Given the research question about the effectiveness of policy, the evaluation of the public objective of social stability, the outcome-oriented approach is applied in this paper. This is in line with the current governance practice worldwide, where an increase in the assessment of policy outcomes in relation to policy objectives has been witnessed (Rauschmayer et al., 2009; Rotberg, 2014). This can be understood if one realised that a smooth or ‘good’ process of governance may not necessarily end up in effective policy (Kelly & Swindell, 2002). Governance of public services (e.g., PRH governance) will therefore evaluate what is perceived as good to the public or by the public. In other words, it is important to know whether the policy makes a difference for the public as recipients of public services (Boaz & Nutley, 2003).

To determine the effectiveness of the governance, the outcomes of governance from the recipients’ perspective have to be compared with the policy objectives (Rauschmayer et al., 2009). The important questions for empirical studies are: what can be taken as the outcomes given the policy objective and how can the objective be translated into measurable and clear variables by which the outcomes can be evaluated (Van den Broeck et al., 2016, p. 65)? As the policy objective will be different in different contexts and one objective may be expressed by multiple (different) outcome indicators, the outcomes also differ from context to context. A detailed examination of the outcomes in the framework of Chinese PRH governance and in the context of the case study Chongqing follows in the next section (Sect. 2.2).

2.2 PRH governance in China and Chongqing

2.2.1 The shift from ‘government’ to ‘governance’ of Chinese PRH

Housing privatization and marketization since 1998 have led to a dramatic rise in housing price in China (Chen et al., 2011). Housing affordability has become a pressing economic and social problem. Therefore, central government determined to provide affordable homes, especially in the form of PRH (Wang & Shao, 2014).

Introduced in 2010, PRH refers to a housing program with government-controlled rents to make this housing affordable for low- and middle-income households, new employees, and migrants with stable employment and residence in cities (MOHURD, 2010). In March of 2011, the Chinese central government issued the 12th Five-Year Plan, which aimed to build 18 million new PRH units in the period 2011–2015. Since then, PRH has become a national housing policy priority (MHURD, National Development and Reform Commission [NDRC], & Mof, 2013).

The provision of PRH used to be organized as follows: central government to be responsible for policy-making, establishing operational methods for the whole country of China, and local governments to be in charge of local policy formulation and implementation (Feng et al., 2007). This model of PRH provision is the so-called ‘government’ mode, which has been criticized in terms of the imbalance in the distribution of the responsibilities between different levels of government: the central government delegates responsibilities without providing adequate financial support for local authorities (Chen et al., 2011; Li et al., 2016). Local governments bear a huge financial burden when realizing new PRH supply. Besides, local governments depend largely on a flourishing real estate market to manage their mounting debt over the past several years, 44 trillion yuan (1 yuan equals to around 0.13 Euro in 2020) in 2018 (Deng, 2019; Nicholas, 2011). Therefore, they are not motivated to provide free or cheap land for PRH projects.

To solve their financial restrictions, local governments turn to market resources and work with non-governmental actors for the funding/financing and management of PRH provision. Central government also issues policies to support the non-governmental actors’ involvement in the provision of PRH (see for examples, MoF & MOHURD, 2015; MOHURD & MoF, 2018a). Regarding the increasing involvement of non-governmental actors, the provision of PRH is moving from the traditional ‘government’ model to ‘governance’ model, where governments and non-governmental actors participate and cooperate in the formulation and implementation of PRH policies (Calavita & Mallach, 2010).

Many studies have been conducted to investigate the one-decade experience of Chinese PRH (Chen et al., 2013; Wang & Shao, 2014; Zhou & Ronald, 2017a). However, there is a lack of studies underpinned by a theoretical foundation from a governance perspective to evaluate PRH empirically. Since the provision of PRH now involves many non-governmental actors and thus became more complex than before, a systematic measurement of PRH governance on the ground is necessary.

2.2.2 The objective and outcomes of PRH governance in China

The ambitious plan to build 18 million new PRH units in the period 2011–2015 is an integral part of the Chinese macro transition, which emphasizes the idea of combining the ‘harmonious society’ of former President Hu in 2006 (Blaxland et al., 2014, p. 511) with ‘people-oriented development’ of President Xi in 2012 (Lü, 2015, p. 86). These notions aim to prioritise common people’s welfare and social harmony ahead of pursuing pure economic growth. ‘Political consolidation’ and ‘social stability’ are also identified as driving forces of PRH development (see, for example, Zhou & Ronald, 2017a; Zou, 2014). Chen et al., (2013, p. 31) explain these key concepts:

the strong push for public (rental) housing has important political implications. While housing price inflation and affordability problems appear as economic imbalances, their underlying causes are deeply rooted political problems in the society.

As the central government has not named one specific housing goal in its policy documents, the starting point for the analysis of the governance of PRH provision is taken as ensuring “political consolidation and social stability” (Shi et al., 2016, p. 224); or formulated as maintaining social stability and preventing social unrest in this paper.

Given the policy objective of social stability, the outcomes to be measured in the paper are tenants’ satisfaction with housing quantity and housing quality, and their willingness to communicate about the housing services that they receive, as outcome of PRH governance (see “Appendix 1” for details).

Studies have confirmed that if people are more satisfied with the public service they receive, they are likely not to do harm to society, which will contribute to the social stability of the society (Huang & Du, 2015). Moreover, a higher satisfaction level might improve the economic, social and psychological status of a recipient, which in turn contributes to the social stability (Frijters et al., 2005). In the case of PRH, satisfaction can be further defined into two dimensions: satisfaction with housing quality and housing quantity.

The Chinese central government intends to provide a sufficient number of dwellings available to the population, the supply of PRH units is a variable that cannot be omitted. It is in line with findings in the literature that quantity is a crucial aspect of PRH-applicants’ perception of housing and their resultant satisfaction (Chan & Adabre, 2019; Swanton, 2009; Yang, 2008). In this study, quantity is expressed as access to PRH in terms of: ‘options to apply’ and ‘waiting time’.

As the Chinese government has expressed the intention to go beyond numbers of supply and include tenants’ perceptions in the performance evaluation (see for example, MoF & MOHURD, 2015; MOHURD & MoF, 2018a), housing quality is also very important. Variables of housing quality adopted as the dimensions of tenants’ satisfaction are classic and abundant in the literature (Djebarni & Al-Abed, 2000; Gan et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019; Lu, 1999; Mohit & Azim, 2012; Waziri et al., 2014). They focus on housing environment, dwelling conditions and management. This paper also regards housing quality as a satisfaction dimension and studies both the physical features of a dwelling (housing condition, accessibility, dwelling size, and maintenance and service) and the neighbourhood environment (specifically attachment and safety aspects).

Besides the aforementioned satisfaction with housing quantity and housing quality, another important aspect to social stability is whether the recipients of public goods want to communicate in the PRH governance. Literature has confirmed that this type of ‘participation’ of recipients of housing services in governance can bring concerns from them into the decision-making process and can contribute to a more transparent and effective bureaucracy system in the eyes of the recipients (Arnstein, 1969; Wong, 2013). In this regard, to promote such active communication can benefit the objective of social stability. Since Chinese governments have advertised the communication between PRH-tenants and government officials as an approach to give tenants what is called the right to participation (Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development [MOHURD], 2018), the communication with the governments thus is regarded as a dimension of outcomes of PRH governance, given the objective of social stability.

It is worth noting that although this paper evaluates tenants’ satisfaction with dimensions of their housing, the starting point is different compared with the conventional satisfaction literature (see for example, Gan et al., 2016; Huang & Du, 2015). The starting point here is to evaluate PRH governance by analysing tenants’ satisfaction with PRH as a dimension of PRH governance outcomes. The argumentation would be that if tenants are more satisfied with the PRH quality and quantity, they are more likely not to do harm to society, which will contribute to the national objective of PRH governance, maintaining social stability. The reverse is also true: if the governance objective were not to maintain social stability, tenants’ satisfaction would not need to be measured. On the other hand, for the conventional satisfaction studies, this would not apply: the reasons to measure tenants’ satisfaction is to explore the factors that influence and may improve tenants’ satisfaction. Another difference between both aims, is that this explorative paper emphasizes another dimension of the governance evaluation, tenants’ willingness to communicate with the local government about housing services. This dimension usually is not included in a conventional satisfaction literature.

2.2.3 The Chongqing case

Chongqing, located in the Mid-West of China (see “Appendix 2” Fig. 1), is one of the four municipalities directly governed by the central government. The economy has developed rapidly in recent years and the GDP ranked fifth in China in 2018 (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2019).

The rapid housing price growth and a fast-growing urbanisation together create inequalities in access to market housing during the last decade (Kai, 2019; National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2019). In response, in 2010, Chongqing municipal government planned to build 40 million square metres PRH to benefit more than 4 million people with housing problem in the city by the end of 2020 (Li, 2010). Until September 2019, Chongqing municipality has allocated about 0.51 million units of PRH to 1.4 million people in the city (Chongqing Daily, 2019).

The total investment of the plan is estimated to amount to about 120 billion Chinese yuan (equals to 15.62 billion Euro in 2020), of which 30% is to be provided by central and Chongqing municipal government. Investment organisations established by the Chongqing municipal government are to provide the remaining amount. That these organisations are able to raise funds for PRH is due to the transfer of Chongqing government land holdings into these entities, which can then be used as collateral for bank credits (Yep & Forrest, 2016). Chongqing investment organisations also invest, provide land, construct, and own PRH units (Zhou & Ronald, 2017b).

PRH in Chongqing is earmarked for people who are over 18 years old and with a stable job to indicate the ability to pay rent (Municipal Land Resources and Housing Authority of Chongqing, 2011). Except for the age and job requirements, applicants should not own any dwelling or they should not have more than 13-square-meter individual living area in order to be qualified. Compared to other cities in China, criteria for applying PRH in Chongqing are more relaxed without asking for an urban HukouFootnote 1 or upper income limit.

The eligible applicants, who meet the requirements, can state a preference of the housing in terms of location and dwelling size. To ensure equitable distribution of the dwellings, Chongqing organises a lottery four times a year (since 2011) to make a selection from the qualified applicants. Once they are assigned a PRH unit, they need to sign a lease contract with the municipal government for at least 1 year up to 5 years, after which they have to re-apply and ascertain continued eligibility. Tenants pay rent to the municipal government. The rent is less than 60% of the rent for commercial housing with the same quality and size. According to the staff from the PRH authority in Chongqing, the collection of rent went quite well. During the stay, tenants can communicate with the street-level government when they have questions and suggestions towards PRH. For PRH community management, tenants are encouraged to get involved into the PRH governance.

3 Methodology

3.1 Case selection

As cities are at the frontier of implementing PRH provision policies, we choose Chongqing as a case study to evaluate PRH governance. The selection of Chongqing was based on two criteria.

The first and foremost criterion was that Chongqing has also been experiencing a shift from ‘government’ to ‘governance’ in PRH provision. The national policies are reflected in local governance practice of PRH in Chongqing (see for example, Municipal Land Resources and Housing Authority of Chongqing, 2011). As concerns the nationwide trend to promote non-governmental actors’ involvement, Chongqing’ PRH provision is also involved other organisations: state-owned banks to provide loans to finance PRH projects; property management companies to offer housing management services; Residents’ CommitteesFootnote 2 (jumin weiyuanhui) and Hongguanjia Property Management AllianceFootnote 3 to provide a way for PRH tenants to consult with management and to get government information and services. Given the non-governmental actors’ increasing involvement, concerns have been raised about how to evaluate this complexity (Chen & Hubbard, 2012).

Second criterion was that no other city in China has carried out such large-scale PRH program as Chongqing did (Zhou & Ronald, 2017a). As indicated before, Chongqing municipality has allocated about 0.51 million units of PRH to 1.4 million people in the city until September 2019 (Chongqing Daily, 2019). Thus, Chongqing can provide us with considerable experience of PRH governance and valuable data through the survey. There are many studies concerning Chongqing’s PRH provision while few of them evaluating its governance (see for example, Gan et al., 2016; Liang & Fan, 2015; Zhou & Musterd, 2018; Zhou & Ronald, 2017b).

The first-built eight residential districts are the focus of this study (see “Appendix 2” Fig. 2). The projects are located between the inner and outer rings of Chongqing. Among them, Minxin Jiayuan (Project 7) and Kangzhuang Meidi (Project 8)-first two PRH constructed projects in Chongqing-are quite close to the urban centre, whereas the other six projects are situated relatively far from the city centre. They cover approximately 9.24 million square meters, which constitute nearly a quarter of the PRH units planned by Chongqing municipality until 2020. The buildings in these projects are quite high ranging from 22 to 34 floors. The eight projects were opened for occupancy in the period 2011–2014. Complete infrastructure facilities, such as transportation, energy, hospitals, schools were integrated.

The location and size of first eight Chongqing PRH projects. Note 1: the size of the blue dots indicates the square meters the corresponding PRH project has. The bigger the size is, the more square meters the project covers. Note 2: project 1 = Chengxi Jiayuan, Project 2 = Yunzhuan Shanshui, Project 3 = Liangjiang Mingju, Project 4 = Chengnan Jiayuan, Project 5 = Kangju Xicheng, Project 6 = Minan Huafu, Project 7 = Minxin Jiayuan, Project 8 = Kangzhuang Meidi. Later in the analysis, we define Minxin Jiayuan and Kangzhuang Meidi as ‘Projects close to city centre’ while ‘Projects far from the city centre’ are the other six ones

3.2 Data collection and analysis

To measure the effectiveness of Chinese PRH governance, this paper adopts an outcome-oriented approach which compares the governance objective with governance outcomes perceived by the final users. Since the objective of Chinese PRH governance is to maintain the social stability, sufficient supply of housing of ‘reasonable’ quality with tenants’ input in the governance of housing provision are taken as the three dimensions of governance outcomes.

Data were obtained from a survey. A questionnaire was designed to collect data about PRH tenants’ satisfaction with housing quantity, housing quality, and their willingness to communicate with the government (street-level government). The questionnaire was designed in three main parts (see “Appendix 3”). Advice of some experienced scholars at Chongqing university and staff from the administrative department for PRH governance in Chongqing were taken on board for the questionnaire design.

The first part collected tenants’ basic socio-economic characteristics such as age, gender, income, etc. The second part was about the level of respondents’ satisfaction with the variables related with PRH quantity and quality measured by 5-point Likert-scales (− 2 = very dissatisfied, − 1 = dissatisfied, 0 = moderate, 1 = satisfied, and 2 = very satisfied). Information about tenants’ willingness of communication with the government via a “yes” or “no” question is also collected in the second part (see “Appendix 3”). The questionnaire consists of one open–response query in the end that asked tenants to indicate any additional comments or suggestions about the PRH project that they live in. Some quotes of this query are referred to in the results and discussion section of this paper to support the line of argumentation.

The name of the PRH project where respondents come from was marked on each questionnaire. This can give not only information about the PRH project, but also especially about how far the tenant lives from the city centre. Where tenants live (e.g. near main city area or far away from the main area) can influence their residential satisfaction (Barcus, 2004; Thomsen & Eikemo, 2010).

A trial survey was conducted with randomly selected 20 respondents in Minxin Jiayuan to test the questionnaire to eliminate ambiguity and misleading questions. Minor revision of the questionnaire was done after the trial survey. The questionnaire was distributed in the eight PRH projects (see “Appendix 2” for details). Due to the constraints of time, staff capacity and finances, a convenience sampling approach was employed to reach the respondents in this explorative study. This approach is a type of non-probability sampling method where the sample is taken from a group of people easy to contact or to reach. This sampling approach has been commonly utilized in many questionnaire studies (Huang & Du, 2015; Moghimi et al., 2016).

The survey was conducted in Chongqing from February to March 2017. The questionnaire is self-administered by means of paper and pen. We gave respondent the one-page questionnaire with items printed on both sides. We introduced ourselves to the respondents by indicating our names and research institution, and explained the anticipated time for filling the questionnaire. When respondents showed difficulties in understanding the items of the questionnaire, we simply provided a clarification. Tenants were required to complete the questionnaire using a pen and to return to us the hard copy of the questionnaire. To show our gratitude, we gave each respondent a small gift after completing the questionnaire. More than 250 questionnaires were distributed and 223 were received. Finally, by excluding 17 incomplete questionnaires, a total of 206 respondents remained.

SPSS was used to perform the statistical analysis of the survey. To compute the overall satisfaction rate, the mean value method is the most commonly used in the housing literature (see for example, Amole, 2009; Cook & Bruin, 1994; Ibem & Azuh, 2016; Mohit & Azim, 2012). The big strength of the mean value method lies at its simplicity and that it takes account of all scores to calculate the average. The disadvantage of the mean value method is that the mean satisfaction scores on many sub-variables are usually clustered in high score regions (Amérigo & Aragones, 1997; Torra, 1997). Thus, it is not easy to know where to put efforts to improve tenants’ overall satisfaction. To deal with this, this paper conducts further analyses by using regression models to figure out the specific determinants of tenants’ overall satisfaction with housing quality and housing quantity (see next paragraph). Ogu’s (2002) method is one way of conducting the mean value method and is adopted in this paper to calculate the respondents’ overall satisfaction rate with housing quantity (HIndex-quantity) and housing quality (HIndex-quality) via Eq. (1):

In Eq. (1), HIndex-r is the overall satisfaction rate of a respondent with r (housing quantity and housing quality); N is the number of sub-variables selected for scaling under the r satisfaction dimension (i.e., housing quantity includes two sub-variables and housing quality includes five sub-variables). While variable n represents the actual score of a respondent on the ith sub-variable in the satisfaction dimension, VARIABLE n is the maximum possible score for the ith sub-variable in the housing quantity and housing quality (in our case the maximum possible scores are both 2).

The assumption of this equation is that one tenant’s scores on all the variables of the Housing quantity (or Housing quality) taken together constitute empirically determined indices of the tenant’s satisfaction with the Housing quantity (or Housing quality). This assumption is first raised by Onibokun (1974) and later verified in many studies (see for example, Awotona, 1990; Mohit & Azim, 2012; Muoghalu, 1984).

To compute tenants’ HIndex-quantity and HIndex-quality can enable the comparison of tenants’ overall satisfaction rate with housing quantity and with housing quality at the same score level, given that housing quantity index combines two sub-variables while housing quality index combines five sub-variables. The computed HIndex-quantity and HIndex-quality can be put in regression analyses as dependent variables to figure out the determinants of tenants’ overall satisfactions towards housing quantity and housing quantity (this is explained in next paragraph).

For providing policy implications to improve PRH governance, this study investigates factors that influence these aforementioned tenants’ perceptions by applying two types of regression analysis.Footnote 4 Multiple linear regression analysis was used to build model 1 and 2 to investigate the possible influential factors of HIndex-quantity and HIndex-quality, respectively. Binary logistic regression analysis was adopted to generate model 3 to identify the predictors of the respondents’ willingness to communicate with the government. The backward-elimination-by-hand approach was used to obtain these models.

We supplemented the survey data with data collected from literature sources such as reports, journals and other published sources. Besides, this paper also utilises interviews from our other works on PRH governance in Chongqing. It is worth noting that these former interviews were not conducted for the PRH evaluation, but are used also as source of information in this paper. These interviews were conducted with practitioners from government and non-governmental actors engaged in Chongqing PRH governance throughout the phases of policy design to implementation and realisation. These interviews aim to provide background information about PRH goverance and build a comprehensive understanding of tenants’ perceptions towards PRH.

4 Results of questionnaires

4.1 Respondent information

Table 1 shows an overview of the socio-economic characteristics of the respondents. There were more female respondents than male. The respondents were almost split between age over and under 40. The majority (35.4%) tenants had a family of three persons, which is quite usual in China. 10.2% and 17.0% of the respondents reported their monthly income per person and household monthly income per person higher than 5000 yuan (US$740), respectively. This is due to the fact that income is not a criterion for the application, and thus some respondents reported a relatively high income. The 19.4% of migrant workers shows that the PRH projects not only benefit the migrant workers, as many studies indicate (Gan et al., 2016; Zhou & Musterd, 2018), but also—in majority—house a lot of local residents. Last, but not least, the majority of the tenants reported more than three years of residence.

4.2 Tenants’ perceptions

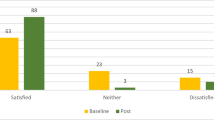

Table 2 shows that the mean scores of every variable regarding the access to PRH (housing quantity) and the characteristic of the housing (housing quality) are above the moderate level (above 0). Furthermore, the mean score of satisfaction regarding accessibility to facilities is the highest among the seven measured variables in Table 2. The interviewees indicated that the municipal government has put a lot of efforts into public transportation development especially for PRH projects. The mean score of housing condition satisfaction is the lowest as nearly one-third of the respondents chose ‘very dissatisfied’ or ‘dissatisfied’ for this category, while on the other dimensions of satisfaction less than 20% of respondent expressed their dissatisfaction. This is also reflected in our conversations with respondents during which they expressed great concern about the physical condition of their dwelling and the structure of PRH units. That the mean score of HIndex-quantity (0.31) is higher than that of HIndex-quality (0.23), is in line with many studies (Gan et al., 2016; Yuan et al., 2018).

Nearly 80% of respondents stated they were willing to communicate with the street-level government (Table 3). During the survey, some respondents expressed that the content of the communication between them and the government was mostly about complaints about housing quality.

4.3 Determinants of PRH tenants’ perceptions

Regression models 1 and 2 in Table 4 investigate the independent variables which influence tenants’ satisfaction with PRH quantity and quality, respectively. Model 1 shows that tenants’ satisfaction index of housing quantity is significantly correlated with their gender, project information, attitudes towards the housing condition and the dwelling size. The combination of these factors can explain 43.0% (adjusted R2 value) of the variation in the tenants’ overall satisfaction rate with housing quantity (HIndex-quantity). Model 2 explains 38.4% (adjusted R2 value) of the variance in relationship with HIndex-quality by including the predictors: project, age, willingness to communicate with government, and tenants’ satisfaction level with the two sub-variables of housing quantity: Waiting time and Options to apply. The adjusted R2 values indicate the two models are relatively well estimated.

It is evident from Model 1 and Model 2 that tenants living close to the city centre appeared to be less satisfied with the housing quantity, but more satisfied with the housing quality compared to those living far from the city centre. Two main reasons can probably explain this result. First, in Chinese big cities like Chongqing, living centrally or nearby means better access to employment and education. Thus, many applicants apply PRH in the two projects close to the city centre and the current tenants living in such projects are more likely to stay if they remain qualified. This makes the waiting time quite long for successfully rent the PRH in the two projects and choices are slim for the new applicants. Second, the two projects close to the city centre were built earlier than other projects and are the so-called pilot projects in Chongqing. Therefore, the supporting facilities are mature and well developed in these two projects, which contributes to residential overall satisfaction rate with the housing quality.

Men were more satisfied with housing quantity than women in Model 1. Compared to those over 50 years, younger respondents (aged between 21 and 30) were less satisfied with housing quality in Model 2. Model 2 also indicates that tenants were more likely to be satisfied with the housing quality, if they wanted to communicate with the government, though the content of communication was about complaints according to the respondents. In addition, respondents with higher satisfaction level of housing condition, accessibility, and dwelling size turned to be more satisfied with the housing quantity. Meanwhile, all two sub-variables under housing quality satisfaction (i.e. Satisfaction options to apply and Satisfaction waiting time) were statistically significant in Model 2.

Model 3 in Table 5 explores the explainable variance of tenants’ willingness to communicate with the street-level government. It shows that tenants from PRH projects close to the city centre were less likely to communicate compared to respondents who lived far from the city centre. As the content of communication was to complain about housing quality, it is not surprising that tenants who lived closed to the city centre (who were more satisfied with housing quality according to Model 1) were not that active in communication.

Migrant workers were less likely to communicate with the government. ‘Mobility’ and ‘no sense of belonging’ as two main characteristics of migrant workers can influence their housing behaviours (Gui et al., 2012; Keung Wong et al., 2007; Lu & Zhou, 2008). For example, migrant workers in many cases show less interests in improving their housing conditions and their living environment (Tao et al., 2014). This is in line with our study that migrant workers did not have a high intention to communicate with the government, while respondents described this way of communication as the main approach for tenants to contribute to the PRH governance.

In addition, when compared to tenants who stayed in PRH projects for more than five years, tenants with a relatively short term (i.e., less than one year and one to two years) were less likely to communicate with the government. This would be in line with findings that a longer term of residence usually gives people a feeling of residential stability and ‘sense of belonging’ (Huang & Du, 2015). This can further motivate them to participate in the governance, in this context, by communication.

The tenants who were more satisfied with dwelling size and maintenance and service turned to be more frequently present in the group who wanted to communicate with government. In contrast, the tenants who were satisfied with waiting time indicated that they did not want to communicate more.

5 Discussion

The results of the survey show that the tenants’ perceptions towards PRH governance were quite mixed given the three crucial dimensions of governance outcomes. The respondents were moderately satisfied with PRH housing quantity, less satisfied with housing quality, and most of them were willing to communicate with local government. This section contextualizes and explains the survey results in the framework of Chinese PRH governance, and compares these findings with the existing studies.

As argued by Driessen et al. (2012) and Bevir et al. (2003), interrelationships amongst actors may contribute to diverse governance features and may also affect the decision-making, policy implementation and thereby the outcomes of policy. Accoringly, this paper explains tenants’ perceptions by two types of interrelationships of PRH governance: first within government levels and second within local governments and other non-governmental actors.

5.1 PRH governance: quality and quantity

Although central government and Chongqing local authority have come to realise the importance of housing quality of PRH and have issued polices to address such problems recently (see for example, Chongqing Daily, 2012; Chongqing Public Rental Housing Administration, 2018; MOHURD & MoF, 2018b; MOHURD, NDRC, MoF, & Ministry of Natural Resources [MNR], 2019), our survey data shows that most respondents were not that satisfied with housing quality variables compared with their attitudes towards housing quantity variables. This is the case even across the whole country, as the relatively low perceived PRH quality keeps popping up in social media news (China Daily, 2014; Tianya Club, 2016). Studies suggest that both the central and local governments should pay more attention to the improving housing quality (Gan et al., 2016; Li et al., 2019; Yuan et al., 2018). Nonetheless, the relatively poor quality of PRH perceived by tenants compared to the perceived housing quantity remains unstudied.

In China, usually central government evaluates the performance of PRH provision by a system in which the number of dwellings that local governments provide is decisive (Zhou & Musterd, 2018). The quantity-oriented measurement approach for the state to evaluate local officials (promotion and dismissal) is an important manifestation of the relationships within government levels (Huang, 2012; Zhou & Ronald, 2017b).

Under this evaluation system, local governments put a lot of efforts into meeting the state’s requirement of constructing PRH units (Yuan et al., 2019). Sometimes the fulfilled PRH units even exceeds the requirement by the central government and this can lead to a waste of resources. In Chongqing, the planned units are 40 million square meters PRH by the end of 2020, while the finished square meters surpassed 50 million by the end of 2015 already (Liang & Fan, 2015). One government official showed his concern about the quantity issue by putting the question “what is the adequate amount of PRH units in Chongqing” (Staff from Municipal Land Resources and Housing Authority of Chongqing, 2017). Another staff member from the local government in Chongqing addressed the over-construction issue of PRH in Chongqing:

The vacancy rate of PRH in the area outside the city centre is not low. This can cause a waste of money. (Staff from Urban and Rural Construction Committee of Chongqing, 2017)

Since the central government only provides a small part of needed funds for investments, local officials responsible for the implementation of PRH mostly depend on their own finances. It is likely that the local authority may want to achieve the set target quantity of PRH units with their limited resources without extra resources to put in improving housing quality. As Huang (2015), Zhou and Ronald (2017b) and many others state, the PRH quality has been shifted to the second plan by the local governments.

The relationships among governments and non-governmental actors might further hinder the Chongqing government to improve PRH housing quality. This is due to that the investment organisations, as the main implementers of PRH construction, are viewed as an extended part of the government bureaucracy, rather than as commercial entities (Yan et al., 2020; Zhou & Ronald, 2017a), as one of the interviewees stated:

We act like an agent of the government and our priority is to fulfil the task assigned by the government. (Staff from Chongqing City Real Estate Group Co., Ltd., 2017)

The relationships between superiors (governments) and their ‘subordinates’ (the investment organisations established by governments) thus can be considered as a vertical one. As the local authorities care more about housing quantity, it can be hard to really make the involving actors themselves organise mutual monitoring of each other on housing quality.

5.2 PRH governance: tenant communication

Scholars argue that citizen participation via communication could enhance local cooperation and improve monitoring of policy implementation (Jing & Besharov, 2014; Warner & Hefetz, 2008). In the case of PRH governance, tenants’ participation through communicating with government is meaningful for PRH provision improvement.

The central and local governments have a consensus of preventing social problems in PRH projects as keeping a stable society is important for economic growth in China (Ringen & Ngok, 2017). Thus, tenants’ participation is encouraged by both levels of government.

In practice, government officials in Chongqing indicated that they have put quite some effort into promoting the so-called “Grid Governance” (Wanggehua zhili) to involve the tenants in PRH governance (staff from Municipal Land Resources and Housing Authority of Chongqing, 2017). The term “Grid Governance” was first introduced by the central government in its 18th CPC Central Committee as an innovation scheme to facilitate citizen participation in community development (Chinese Communist Party, 2013). It is to divide one community into several grid units based on their geographical and administrative boundaries. Within these grid units, governmental actors as well as non-governmental actors provide community-oriented social services on a daily basis (Tang, 2019). People living in such units can share their opinions with these actors in order to influence the governance. There were some tenant representatives working as volunteers to help build the connection between tenants and government. Therefore, the usage of Grid Governance is expected to help prevent large-scale social unrest and to build social stability (Bai et al., 2017).

In Chongqing, local government has encountered financial constraints as well as human resource constraints in terms of the implementation of Grid Governance (Yan et al., 2020). Consequently, local government requires Residents’ Committees, establishes Hongguanjia Property Management Alliance, and hires property management companies to help manage PRH neighbourhood. Thus, the involvement of these non-governmental actors has come about from capacity and financial constraints, involving other actors in the governance to help out government.

As aforementioned, PRH tenants can get involved in the governance by communicating with these actors in terms of housing provision and housing management, as these are the phases of governance that tenants are aware of. Since the activities of these actors are restrained by lowest level governments according to the interviews, the tenants’ participation is triggered by the government rather than by bottom-up initiatives. Grid Governance allows for involvement of tenants in the daily management of PRH on government terms rather than involvement in decision-making around PRH-provision (Li et al., 2019; Lin, 2018; Mok, 1988; Xu & Chow, 2006).

However, this type of involvement of tenants in Chongqing is perceived as positive by the involved tenants in two ways. First, the survey shows that nearly 80% of the respondents expressed a willingness to communicate with the government. This is actually quite high since it is not common in China that people really interact with government directly (Xu & Chow, 2006). The high percentage of the willingness to communicate is the first step for tenants to really get involved and then influence the governance. Second, such tenant participation provides a way for tenants to complain about housing quality. Some respondents indicated in the end of the questionnaire that they would go to the property management company and ask the company to help solve housing quality issues. In conclusion, the results of the regression analysis in Model 2 reveal that if the tenants were willing to participate in the governance in the way of communicating complaints, they were more likely to be satisfied with their housing quality.

6 Conclusion and implications

The Chinese PRH scheme is to provide decent and affordable rental homes to households that need help in accessing housing. PRH is the largest and most flexible form of public housing in China described in the literature and in policy documents (Chinese Communist Party, 2013). Although the provision of PRH is moving towards a ‘governance’ model, no studies underpinned by a theoretical foundation from a governance perspective have attempted to investigate whether the PRH governance works on the ground. This empirical explorative study aims to fill this knowledge gap, from the tenant’s perspective.

The adopted outcome-oriented evaluation, which focuses on the effectiveness of public objectives, compares the government objectives with the outcomes, in this case from the perspective of final users: PRH tenants. As the aim of PRH governance in China is to maintain social stability in society, sufficient supply of housing of ‘reasonable’ quality with tenants’ input in the governance of housing provision are argued to be the three crucial dimensions of governance outcomes: accessibility of PRH units in terms of waiting time and allocation process; the quality of those units in terms of size and access to services, among others; and communication of tenants with local government about housing services.

The empirical examination took place in Chongqing, the most important pilot city of PRH provision in China. A questionnaire survey was conducted among tenants in the first eight PRH projects that were realized in the city. Besides, scientific literature, policy documents and government reports relevant to the practice of PRH governance in China and in Chongqing, as well as interviews from our other works are utilised as secondary data to support the discussion. The results show that the PRH tenants perceived PRH governance outcomes quite mixed. They were moderately satisfied with PRH housing quantity, less satisfied with housing quality, while most of them were willing to communicate with local government.

Based on two types of regression analysis as well as the interview data, policy implications for PRH governance improvements in the eyes of the tenants can be formulated. In line with studies by Gan et al. (2016), Huang and Du (2015), and Zhou and Musterd (2018), the findings of this study show that it is important for government to enhance the physical condition of the dwelling. Furthermore, the accessibility to facilities, the dwelling size, the housing maintenance and service also need to be improved. It is also important for the local government to provide more options for tenants to apply and to improve the efficiency of the application process by shortening the waiting time. In addition, findings show that if local governments continue the promotion of tenants’ communication with the local government, tenants will be more satisfied with governance outcomes. Last, but not least, if tenants with different socio-economic characteristics are treated differently according to their preferences on the three dimensions, their satisfaction will increase.

Given that the reasons for the governance outcomes are rooted in inter-government relationships and in the relationships among local government and non-governmental actors, PRH governance will benefit when government: (1) rethinks and redevelops the performance evaluation system to include other indicators than number of PRH units only; (2) rethinks the relations with non-governmental actors and organises a monitoring system that will assist in optimizing housing quality that will satisfy the residents; and (3) facilitates tenants’ communication with local government in order to contribute to a preferred governance outcome in the eyes of the tenants.

This study might shed light on ways forward to strengthen the effectiveness of the public objective of social stability by PRH governance in other Chinese cities. This is due to that other Chinese cities have witnessed two phenomena similar to Chongqing: the relatively low dwelling quality compared to housing numbers provided and a nationwide promotion of tenants’ participation. However, this study does not have the intention to use Chongqing to represent China as China is such a big country with many local variations. Further empirical data will be needed about tenant outcomes evaluation in other Chinese cities in order to be able to conclude about more general applicability of outcomes. In addition, this study might have wider implications beyond China. The shift towards a governance model of PRH provision in China parallels the trend worldwide where the direct production of affordable housing on the part of the central (federal) government has largely diminished, while a multisectoral, decentralized housing provision system has emerged in its place (Czischke, 2007; Gasparre, 2011; Lee & Ronald, 2012; Leviten-Reid et al., 2019). The measurement of housing governance has been widely discussed in the international literature. Through adopting the outcome-oriented approach, this paper contributes to the literature by moving beyond simple descriptions of governance measurement to empirically measuring the perceptions of the final users.

Notes

Urban Hukou is an official document issued by the Chinese government, certifying that the holder is a legal resident of a particular city.

The Residents’ Committees is a basic unit of urban governance in China and is originally defined as ‘mass organization of self-management at the grassroots level’ in the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (1993).

Hongguanjia Property Management Alliance is a special organization established by Chongqing local government in 2015. It provides services to PRH-tenants and manages the neighbourhood by building cooperation among the government, property management companies, tenants, etc. (staff from Hongguanjia Property Management Alliance in Chongqing, 2017).

Multiple linear regression is adopted when the dependent variable is continual while binary logistic regression is used for dichotomous or binary dependent variable.

References

Amérigo, M. A., & Aragones, J. I. (1997). A theoretical and methodological approach to the study of residential satisfaction. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 17(1), 47–57.

Amole, D. (2009). Residential satisfaction in students’ housing. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 29(1), 76–85.

Anten, L. (2009). Strengthening governance in post-conflict fragile states. The Hague: Clingendael. Retrieved June 6, 2020 from http://www.clingendael.nl/sites/default/files/20090610_cru_anten_postconflict.pdf.

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224.

Awotona, A. (1990). Nigerian government participation in housing: 1970–1980. Habitat International, 14(1), 17–40.

Bai, X., Muhammad Imran, H., Li, F., Muhammad Shehzad, H., & Gu, Y. (2017). An empirical study on application and efficiency of gridded management in public service supply of Chinese Government. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management, 8, 2–15.

Barcus, H. (2004). Urban-rural migration in the USA: An analysis of residential satisfaction. Regional Studies, 38(6), 643–657.

Bevir, M., Rhodes, R. A., & Weller, P. (2003). Traditions of governance: Interpreting the changing role of the public sector. Public Administration, 81(1), 1–17.

Blaxland, M., Shang, X., & Fisher, K. R. (2014). Introduction: People oriented: A new stage of social welfare development in China. Journal of Social Service Research, 40(4), 508–519.

Boaz, A., & Nutley, S. (2003). Evidence-based policy and practice. Routledge.

Bovaird, T., & Löffler, E. (2003). Evaluating the quality of public governance: Indicators, models and methodologies. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 69(3), 313–328.

Buduru, B., & Pal, L. A. (2010). The globalized state: Measuring and monitoring governance. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 13(4), 511–530.

Calavita, N., & Mallach, A. (2010). Inclusionary housing in international perspective: Affordable housing, social inclusion, and land value recapture. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Chan, A. P., & Adabre, M. A. (2019). Bridging the gap between sustainable housing and affordable housing: The required critical success criteria (CSC). Building and Environment, 151(15), 112–115.

Chen, C., & Hubbard, M. (2012). Power relations and risk allocation in the governance of public private partnerships: A case study from China. Policy and Society, 31(1), 39–49.

Chen, J., Guo, F., & Wu, Y. (2011). One decade of urban housing reform in China: Urban housing price dynamics and the role of migration and urbanization, 1995–2005. Habitat International, 35(1), 1–8.

Chen, J., Jing, J., Man, Y., & Yang, Z. (2013). Public housing in mainland china: History, ongoing trends, and future perspectives. In The future of public housing (pp. 13–35). Springer: Berlin, Germany.

China Daily. (2014). Public rental housing: Public transpotation is not convenient, quality is not high, application is not easy. Retrieved May 27, 2019 from http://cnews.chinadaily.com.cn/2014-09/12/content_18590109.htm.

Chinese Communist Party. (2013). The decision on major issues concerning comprehensively deepening reforms. China. Retrieved January 20, 2019 from http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2013-11/15/content_2528179.htm.

Chongqing Daily. (2012). "Zero tolerance" launched by Liangjiang District for public rental housing low quality issues. Retrieved February 28, 2020 from http://www.liangjiang.gov.cn/Content/2012-08/26/content_5783.htm.

Chongqing Daily. (2019). Chongqing municipality has allocated 0.5 million units of PRH to benefit 1.4 million people in the city. Retrieved April 3, 2020 from http://zfcxjw.cq.gov.cn/xygl/zfbzxx/gzdt/2019-09-25-12794164.html.

Chongqing Public Rental Housing Administration. (2018). Chongqing Public Rental Housing Administration held a briefing on the situation of "quality improvement year" inspection. Retrieved February 28, 2020 from http://gzf.zfcxjw.cq.gov.cn/gongzdt/201809/t20180930_4518.htm.

Cook, C. C., & Bruin, M. J. (1994). Determinants of housing quality: A comparison of white, African-American, and Hispanic single-parent women. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 15(4), 329–347.

Czischke, D. (2007). A policy network perspective on Social Housing Provision in the European Union: The case of CECODHAS. Housing, Theory and Society, 24(1), 63–87.

Deng, C. (2019). Bills come due for China’s Local Governments. Retrieved June 5, 2020 from https://www.wsj.com/articles/bills-come-due-for-chinas-local-governments-11577467587..

Deng, F. (2018). A theoretical framework of the governance institutions of low-income housing in China. Urban Studies, 55(9), 1967–1982.

Djebarni, R., & Al-Abed, A. (2000). Satisfaction level with neighbourhoods in low-income public housing in Yemen. Property Management, 18(4), 230–242.

Driessen, P. P., Dieperink, C., Laerhoven, F., Runhaar, H. A., & Vermeulen, W. J. (2012). Towards a conceptual framework for the study of shifts in modes of environmental governance–experiences from the Netherlands. Environmental Policy and Governance, 22(3), 143–160.

Ehler, C. N. (2003). Indicators to measure governance performance in integrated coastal management. Ocean & Coastal Management, 46(3–4), 335–345.

Feng, N., Lu, J., & Zhu, Y. (2007). Research on the construction model of social housing. Construction Economy, 8, 27–30.

Freyburg, T., Lavenex, S., Schimmelfennig, F., Skripka, T., & Wetzel, A. (2009). EU promotion of democratic governance in the neighbourhood. Journal of European Public Policy, 16(6), 916–934.

Frijters, P., Haisken-DeNew, J. P., & Shields, M. A. (2005). Socio-economic status, health shocks, life satisfaction and mortality: Evidence from an increasing mixed proportional hazard model. Center for Economic Policy Research Discussion Paper No. 496.

Gan, X., Zuo, J., Ye, K., Li, D., Chang, R., & Zillante, G. (2016). Are migrant workers satisfied with public rental housing? A study in Chongqing, China. Habitat International, 56, 96–102.

Gasparre, A. (2011). Emerging networks of organized urban poor: Restructuring the engagement with government toward the inclusion of the excluded. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 22(4), 779–810.

Gui, Y., Berry, J. W., & Zheng, Y. (2012). Migrant worker acculturation in China. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(4), 598–610.

Haarich, S. N. (2018). Building a new tool to evaluate networks and multi-stakeholder governance systems. Evaluation, 24(2), 202–219.

Heinrich, C. J. (2002). Outcomes-based performance management in the public sector: Implications for government accountability and effectiveness. Public Administration Review, 62(6), 712–725.

Hertting, N., & Vedung, E. (2012). Purposes and criteria in network governance evaluation: How far does standard evaluation vocabulary takes us? Evaluation, 18(1), 27–46.

Huang, Y. (2012). Low-income housing in Chinese cities: Policies and practices. The China Quarterly, 212, 941–964.

Huang, Y. (2015). Bolstering inclusionary housing in Chinese cities. Chicago, US: Paulson Policy Memorandum.

Huang, Z., & Du, X. (2015). Assessment and determinants of residential satisfaction with public housing in Hangzhou, China. Habitat International, 47, 218–230.

Ibem, E. O., & Azuh, D. E. (2016). Satisfaction with public housing among urban women in Ogun State, Nigeria. Covenant Journal of Research in the Built Environment, 1(2), 67-90.

Ismail, A. (2010). Director’s integrity: An assessment of corporate integrity. Conference Paper: Finance and Corporate Governance Conference, April 28–29, Melbourne.

Jiefang Daily. (2017). Shanghai improves the housing providing system emphasising equal importance of housing purchase and renting, and provided more than 110,000 public rental housing. Retrieved June 8, 2020 from https://www.chinanews.com/cj/2017/11-08/8371147.shtml..

Jing, Y., & Besharov, D. J. (2014). Collaboration among government, market, and society: Forging partnerships and encouraging competition. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 33(3), 835–842.

Kai, F. (2019). National house price-to-income ratio in 2018. Retrieved February 17, 2020 from http://finance.sina.com.cn/china/gncj/2019-03-26/doc-ihsxncvh5614636.shtml.

Kaufmann, D., & Kraay, A. (2007). On measuring governance: Framing issues for debate. In: Roundtable on Measuring Governance Hosted by the World Bank Institute and the Development Economics Vice-Presidency of The World Bank.

Kelly, J. M., & Swindell, D. (2002). A multiple-indicator approach to municipal service evaluation: Correlating performance measurement and citizen satisfaction across jurisdictions. Public Administration Review, 62(5), 610–621.

Keung Wong, D. F., Li, C. Y., & Song, H. X. (2007). Rural migrant workers in urban China: Living a marginalised life. International Journal of Social Welfare, 16(1), 32–40.

Kooiman, J. (2003). Governing as governance. London, UK: Sage.

Lee, H., & Ronald, R. (2012). Expansion, diversification, and hybridization in Korean public housing. Housing Studies, 27(4), 495–513.

Leviten-Reid, C., Matthew, R., & Mowbray, O. (2019). Distinctions between non-profit, for-profit, and public providers: The case of multi-sector rental housing. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 30(3), 578-592.

Li. (2010). Chongqing is going to build 40 million square metres PRH. Retrieved April 8, 2020 from http://finance.sina.com.cn/stock/t/20100325/02367627303.shtml.

Li, D., Guo, K., You, J., & Hui, E.C.-M. (2016). Assessing investment value of privately-owned public rental housing projects with multiple options. Habitat International, 53, 8–17.

Li, J., Stehlík, M., & Wang, Y. (2019). Assessment of barriers to public rental housing exits: Evidence from tenants in Beijing, China. Cities, 87, 153–165.

Liang, P., & Fan, J. (2015). Urban low-cost housing management in Chongqing under the new urbanization background. High Architecture Education. Retrieved April 10, 2020 from http://qks.cqu.edu.cn/gdjzjyen/article/abstract/201502042?st=article_issue.

Lin, Y. (2018). An institutional and governance approach to understand large-scale social housing construction in China. Habitat International, 78, 96–105.

Lü, J. (2015). The socialist reform with Chinese characteristics under the guidance of Chinese spirit. Cross-Cultural Communication, 11(5), 85–88.

Lu, M. (1999). Determinants of residential satisfaction: Ordered logit vs. regression models. Growth and change, 30(2), 264–287.

Lu, P., & Zhou, T. (2008). Housing for rural migrant workers: Consumption characteristics and supply policy. Urban Policy and Research, 26(3), 297–308.

Mayntz, R. (2003). From government to governance: Political steering in modern societies. presented at Summer Academy on IPP, Wuerzburg, September 7-11. http://www.ioew.de/governance/english/veranstaltungen/SummerAcademies/SuA2Mayntz.pdf. Summer Academy on IPP, 7–11.

MHURD, National Development and Reform Commission [NDRC], & Mof. (2013). Announcement on unify low-rent housing and Public Rental Housing Provision. Retrieved January 10, 2021 from http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/zcfg/jsbwj_0/jsbwjzfbzs/201312/t20131206_216468.html..

Ministry of Finance [MoF]. (2015). Notice on promoting the construction and operation management of Public Rental Housing investment by using the model of government and social capital cooperation. Retrieved December 17, 2019 from http://jrs.mof.gov.cn/ppp/zcfbppp/201505/t20150526_1240826.html..

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development [MOHURD]. (2018). Notice of the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development and the Ministry of Finance on Promoting the Pilot Program for the Government to Purchase Operational Management Services for Public Rental Housing. Retrieved December 17, 2019 from http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/wjfb/201810/t20181016_237917.html..

MoF, & MOHURD. (2015). Notice about the Interim Measures for the Administration of Financial Fund for Public Housing. Retrieved December 17, 2019 from http://www.mof.gov.cn/zhengwuxinxi/caizhengwengao/wg2015/wg201504/201509/t20150916_1458706.html.

Moghimi, V., Jusan, M. B. M., & Izadpanahi, P. (2016). Iranian household values and perception with respect to housing attributes. Habitat International, 56, 74–83.

Mohit, M. A., & Azim, M. (2012). Assessment of residential satisfaction with public housing in Hulhumale’, Maldives. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 50, 756–770.

MOHURD. (2010). Guanyu jiakuai fazhan gonggong zulin zhufang de zhidao yijian (Suggestions for accelerating the development of public rental housing). Retrieved January 5, 2019 from http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/wjfb/201006/t20100612_201308.html.

MOHURD, & MoF. (2018a). Notice on implementing pilot programs for government’s purchase operations management service of public rental housing projects. Retrieved June 5, 2020 from http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/wjfb/201810/t20181016_237917.html.

MOHURD, & MoF. (2018b). Notice on implementing pilot programs for government’s purchase operations management service of public rental housing projects No. 92 [2018]. Retrieved June 6, 2020, from http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/wjfb/201810/t20181016_237917.html.

MOHURD, NDRC, MoF, & Ministry of Natural Resources [MNR]. (2019). Opinions on further standardizing the development of public rental housing. Retrieved May 27, 2019, from http://www.mohurd.gov.cn/wjfb/201905/t20190517_240600.html.

Mok, B.-H. (1988). Grassroots organizing in China: The residents’ committee as a linking mechanism between the bureaucracy and the community. Community Development Journal, 23(3), 164–169.

Municipal Land Resources and Housing Authority of Chongqing. (2011). Detailed rules for the implementation of Public Rental Housing in Chongqing. Retrieved April 1, 2019 from http://chongqing.chashebao.com/ziliao/17652.html.

Muoghalu, L. N. (1984). Subjective indices of housing satisfaction as social indicators for planning public housing in Nigeria. Social Indicators Research, 15(2), 145–164.

National Bureau of Statistics of China. (2019). Statistical data for different cities. Retrieved March 29, 2020 from http://data.stats.gov.cn/index.htm.

Nicholas, B. (2011). The link between China's Property Market and Local Government Finances. Retrieved May 19, 2020 from https://www.piie.com/blogs/china-economic-watch/link-between-chinas-property-market-and-local-government-finances.

Ogu, V. (2002). Urban residential satisfaction and the planning implications in a developing world context: The example of Benin City, Nigeria. International Planning Studies, 7(1), 37–53.

Onibokun, A. G. (1974). Evaluating consumers’ satisfaction with housing: An application of a systems approach. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 40(3), 189–200.

Patton, W. D., & Director, C. (2008). What is good governance? Policy Perspectives, 29(05), 2008.

Peters, B. G., & Pierre, J. (1998). Governance without government? Rethinking public administration. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 8(2), 223–243.

Rauschmayer, F., Berghöfer, A., Omann, I., & Zikos, D. (2009). Examining processes or/and outcomes? Evaluation concepts in European governance of natural resources. Environmental Policy and Governance, 19(3), 159–173.

Rhodes, R. A. W. (1996). The new governance: Governing without government. Political Studies, 44(4), 652–667.

Ringen, S., & Ngok, K. (2017). What kind of welfare state is emerging in China? In Towards universal health care in emerging economies (pp. 213–237). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rotberg, R. I. (2014). Good governance means performance and results. Governance, 27(3), 511–518.

Shi, W., Chen, J., & Wang, H. (2016). Affordable housing policy in China: New developments and new challenges. Habitat International, 54, 224–233.

Stoker, G. (1998). Governance as theory: Five propositions. International Social Science Journal, 50(155), 17–28.

Swanton, S. (2009). Social housing wait lists and the one-person household in Ontario. Retrieved May 20, 2020 from https://uwspace.uwaterloo.ca/bitstream/handle/10012/5922/Swanton_Suzanne.pdf?sequence=3.

Tang, B. (2019). Grid governance in China's urban middle-class neighbourhoods. The China Quarterly, 241, 43–61.

Tao, L., Wong, F. K., & Hui, E. C. (2014). Residential satisfaction of migrant workers in China: A case study of Shenzhen. Habitat International, 42, 193–202.

Thomsen, J., & Eikemo, T. A. (2010). Aspects of student housing satisfaction: A quantitative study. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, 25(3), 273–293.

Tianya Club. (2016). The poor quality of PRH units. Retrieved May 27 2019 from http://bbs.tianya.cn/post-45-1746165-1.shtml.

Torra, V. (1997). The weighted OWA operator. International Journal of Intelligent Systems, 12(2), 153–166.

Van den Broeck, K., Haffner, M., & Winters, S. (2016). An evaluation framework for moving towards more cost-effective housing policies. HIVA – KU Leuven, Leuven.

Wang, Y. P., & Shao, L. (2014). Urban housing policy changes and challenges in China. In J. Doling & R. Ronald (Eds.), Housing east asia: Socioeconomic and demographic challenges (pp. 40–70). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Warner, M. E., & Hefetz, A. (2008). Managing markets for public service: The role of mixed public–private delivery of city services. Public Administration Review, 68(1), 155–166.

Waziri, A. G., Yusof, N. A., & Abd Rahim, N. M. S. (2014). Occupants housing satisfaction: does age really matter? Urban, Planning and Transport Research, 2(1), 341–353.

Wong, P. -H. (2013). The public and geoengineering decision-making: A view from Confucian political philosophy. Techné: Research in Philosophy and Technology, 17(3), 350–367.

Xinhua net. (2018). Beijing Affordable Housing Center: Public rental housing projects have benefited more than 100,000 residents. Retrieved June 8, 2020 from http://www.xinhuanet.com/2018-03/11/c_1122520241.htm.

Xu, Q., & Chow, J. C. (2006). Urban community in China: Service, participation and development. International Journal of Social Welfare, 15(3), 199–208.

Yan, J., Haffner, M., & Elsinga, M. (2020). Embracing market and civic actor participation in public rental housing governance: new insights about power distribution. Housing Studies, 1–24.

Yang, Y. (2008). A tale of two cities: Physical form and neighborhood satisfaction in metropolitan Portland and Charlotte. Journal of the American Planning Association, 74(3), 307–323.

Yep, R., & Forrest, R. (2016). Elevating the peasants into high-rise apartments: The land bill system in Chongqing as a solution for land conflicts in China? Journal of Rural Studies, 47, 474–484.

Yuan, J., Li, W., Xia, B., Chen, Y., & Skibniewski, M. J. (2019). Operation performance measurement of public rental housing delivery by PPPS with fuzzy-AHP comprehensive evaluation. International Journal of Strategic Property Management, 23(5), 328–353.

Yuan, J., Li, W., Zheng, X., & Skibniewski, M. J. (2018). Improving operation performance of public rental housing delivery by PPPs in China. Journal of Management in Engineering, 34(4). 4018015.

Zhang, F., Zhang, C., & Hudson, J. (2018). Housing conditions and life satisfaction in urban China. Cities, 81, 35–44.

Zhou, J., & Musterd, S. (2018). Housing preferences and access to public rental housing among migrants in Chongqing, China. Habitat International, 79, 42–50.

Zhou, J., & Ronald, R. (2017a). Housing and welfare regimes: Examining the changing role of public housing in China. Housing, Theory and Society, 34(3), 253–276.

Zhou, J., & Ronald, R. (2017b). The resurgence of public housing provision in China: The Chongqing programme. Housing Studies, 32(4), 428–448.

Zou, Y. (2014). Contradictions in China’s affordable housing policy: Goals vs. structure. Habitat International, 41, 8–16.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: The governance outcome dimensions from PRH tenants’ perceptions

Dimensions | Questions for PRH-tenants (variables) | |

|---|---|---|

Housing quantity satisfaction | Are you satisfied with | Options to apply (the location and number of housing available for application) |

Waiting time (the time of tenants before being assigned a PRH unit) | ||

Housing quality satisfaction | Are you satisfied with | Housing condition (actual living condition) |

Accessibility to public transportation, community and shopping facilities, etc | ||

Dwelling size | ||

Maintenance and service (of housing units and the surrounding environment) | ||

Quality of the neighbourhood environment (feeling of attachment, safety and security) | ||

Willingness to communicate with the government (the street-level government) | When you have questions or suggestions, do you want to communicate with the government? | |

Appendix 2: Maps of China, Chongqing, and eight Chongqing PRH projects

Appendix 3: Questionnaire distributed in Chongqing

Public Rental Housing Tenants’ Perception Questionnaire (name of the PRH project, for instance: Minxin Jiayuan)

-

1.

Basic socio-economic characteristics

-

1.1

What is your gender?

☐ Male ☐ Female

-

1.2

What is your age?

☐ 21–30 ☐ 31–40 ☐ 41–50 ☐ Above 50

-

1.3

What is the composition of the households?

☐ 1 person ☐ 2 person ☐ 3 person ☐ 4 person ☐ 5 person ☐ more than 5 person

-

1.4

What is your average income per month?

☐ < 2000 yuan ☐ 2001–3000 yuan ☐ 3001–5000 yuan ☐ 5000–10,000 yuan

-

1.5

What is the average income per household per month in your family?

☐ < 2000 yuan ☐ 2001–3000 yuan ☐ 3001–5000 yuan ☐ 5001–10,000 yuan

-

1.6

What is your job?

☐ Migrant workers

☐ Other jobs

-

1.7

How long have you been living in the house?

☐ Less than one year ☐ 1–2 years ☐ 2–3 years ☐ 3–4 years ☐ 4–5 years ☐ More than 5 years

-

2.

Views on the housing quantity and housing quality and willingness to communicate with the government

-

2.1

To what extend are you satisfied with the housing quantity?

Level of satisfaction with housing quantity | Very satisfied (2) | Satisfied (1) | Moderate (0) | Dissatisfied (-1) | Very dissatisfied (-2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Options to apply | |||||

Waiting time |

-

2.2

To what extend are you satisfied with the housing quality?

Level of satisfaction with housing quality | Very satisfied (2) | Satisfied (1) | Moderate (0) | Dissatisfied (-1) | Very dissatisfied (-2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Housing condition | |||||

Dwelling Size | |||||

Accessibility | |||||

Maintenance and service | |||||

Quality of the neighbourhood environment |

-

2.3

When you have questions or suggestions, are you willing to communicate with the government? ☐ Yes ☐ No

-

If the answer is “no”, how did you solve it?

-

____________

-

-

3.

Additional comments or suggestions

-

Is there any other matter you think is important to mention about the topics that we have discussed?

-

☐ Yes (please explain it) _________________

-

☐ No

-

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article