Abstract

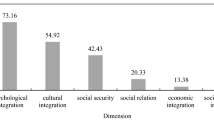

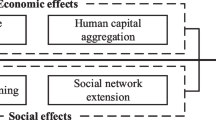

Migrants are important parts of China’s urban population, but still limited knowledge is known about the contextual determinants of their socio-economic integration in Chinese cities. Based on a large national micro-level data extracted from the 2014 China Migrant Dynamic Survey, we extend the literature on migrants’ socio-economic integration by examining the relationships between neighbourhood types and different dimensions of socio-economic integration. Our multi-dimensional index of socio-economic integration covers economic, socio-cultural and identity perspectives. The results show that migrants demonstrate significantly higher levels of overall socio-economic integration when living in formal neighbourhoods (composed of commercial properties, work unit and affordable housing), compared with those residing in informal neighbourhoods (e.g. urban villages). Moreover, migrants living in commercial property neighbourhoods are best integrated economically, and those living in affordable and work unit housing neighbourhoods are more socio-culturally integrated than others. Inner city old housing neighbourhoods are positively associated with socio-cultural integration, compared with urban villages, while both neighbourhood types are negatively correlated with identity integration. Our findings remain robust after controlling for potential endogeneity bias caused by migrants’ self-selection into different neighbourhood types. We conclude that neighbourhood types do matter for migrants’ socio-economic integration but there is large heterogeneity of the correlations across different migrant groups.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

According to previous studies, informal housing settlements are characterized with substandard housing units, over-crowding, insecure housing tenure and insufficient service provision (Liu et al. 2013; Ouyang et al. 2017). In our paper, inner-city old housing awaiting regeneration has the above features including obsolete houses with minimal living space, traffic congestion and overcrowding. Housing tenure is not secure due to demolition and regeneration in the near future. Therefore, it belongs to informal housing. It does not overlay with inner-city work-unit housing that is still in good building conditions.

Standardized formula: factor vale after conversion = (factor value + B) × A; A = 99/(MAX(factor value) − MIN((factor value)); B = 1/A − MIN((factor value)).

References

Ager, A., & Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration. A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies,21(2), 166–191.

Bai, H. (2011). Using propensity score analysis for making causal claims in research articles. Educational Psychology Review,23, 273–278.

Becker, S. O., & Ichino, A. (2002). Estimation of average treatment effects based on propensity scores Estimation of. The Stata Journal,2(4), 358–377.

Chen, Y. (2011). Occupational attainment of migrants and local workers: Findings from a survey in Shanghai’s manufacturing sector. Urban Studies,48(1), 3–21.

Chen, Y., & Wang, J. (2015). Social integration of new-generation migrants in Shanghai China. Habitat International,49, 419–425.

Dehejia, R. H., & Wahba, S. (2002). Propensity score-matching methods for nonexperimental causal studies. Review of Economics and Statistics,84(1), 151–161.

Démurger, S., Gurgand, M., Li, S., & Yue, X. (2009). Migrants as second-class workers in urban China? A decomposition analysis. Journal of Comparative Economics,37(4), 610–628.

Forrest, R., & Kearns, A. (2001). Social cohesion, social capital and the neighbourhood. Urban Studies,38(12), 2125–2143.

Forrest, R., & Yip, N. M. (2007). Neighbourhood and neighbouring in contemporary Guangzhou. Journal of Contemporary China,16(50), 47–64.

Goldlust, J., & Richmond, A. H. (2006). A multivariate model of immigrant adaptation. International Migration Review,8(2), 193.

Gordon, M. M. (1964). Assimilation in American life: The Role of Race, Religion, and National Origins. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hainmueller, J., Hangartner, D., & Pietrantuono, G. (2016). Catalyst or crown: Does naturalization promote the long-term social integration of immigrants? SSRN.

He, X. (2010). Applied multivariate statistical analysis. Beijing: China Statistics Press. (in Chinese).

Huang, Y., & Tao, R. (2015). Housing migrants in Chinese cities: Current status and policy design. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy,33(3), 640–660.

Joffe, M. M., & Rosenbaum, P. R. (1999). Invited commentary: Propensity scores. American Journal of Epidemiology,150(4), 327–333.

Kearns, A., & Whitley, E. (2015). Getting there? The effects of functional factors, time and place on the social integration of migrants. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies,41(13), 2105–2129.

Laurence, J. (2011). The effect of ethnic diversity and community disadvantage on social cohesion. European Sociological Review,27(1), 70–89.

Letki, N. (2008). Does diversity erode social cohesion? Social capital and race in british neighbourhoods. Political Studies,56(1), 99–126.

Lin, Y., Zhang, Q., Chen, W., & Ling, L. (2017). The social income inequality, social integration and health status of internal migrants in China. International Journal for Equity in Health,16(1), 139.

Liu, L., Huang, Y., & Zhang, W. (2018). Residential segregation and perceptions of social integration in Shanghai, China. Urban Studies,55(7), 1484–1503.

Liu, Z., Wang, Y., & Tao, R. (2013). Social capital and migrant housing experiences in urban China: A structural equation modeling analysis. Housing Studies,28(8), 1155–1174.

Liu, Y., Zhang, F., Wu, F., Liu, Y., & Li, Z. (2017). The subjective wellbeing of migrants in Guangzhou, China: The impacts of the social and physical environment. Cities,60, 333–342.

Logan, J. R., & Spitze, G. D. (2002). Family neighbors. American Journal of Sociology,100(2), 453–476.

Lu, Y., Ruan, D., & Lai, G. (2013). Social capital and economic integration of migrants in urban China. Social Networks,35(3), 357–369.

Ma, J., Dong, G., Chen, Y., & Zhang, W. (2018). Does satisfactory neighbourhood environment lead to a satisfying life? An investigation of the association between neighbourhood environment and life satisfaction in Beijing. Cities,74, 229–239.

McCaa, R. (1989). Isolation or assimilation? A log linear interpretation of Australian marriages, 1947–1960, 1975, and 1986. Population Studies,43(1), 155–162.

National Population and Family Planning Commission of P.R. China (PFPC). (2015). Report on China’s Migrant Population Development 2015. Beijing: China Population Press.

National Population and Family Planning Commission of P.R. China (PFPC). (2017). Report on China’s Migrant Population Development 2017. Beijing: China Population Press.

Niu, G., & Zhao, G. (2018). Identity and trust in government: A comparison of locals and migrants in urban China. Cities,83, 54–60.

Ouyang, W., Wang, B., Tian, L., & Niu, X. (2017). Spatial deprivation of urban public services in migrant enclaves under the context of a rapidly urbanizing China: An evaluation based on suburban Shanghai. Cities,60, 436–445.

Park, R. E. (1928). Human migration and the marginal man. American Journal of Sociology,33(6), 881–893.

Piller, I., & Takahashi, K. (2011). Linguistic diversity and social inclusion. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism,14(4), 371–381.

Portes, A., & Zhou, M. (1993). The new second generation: Segmented assimilation and its variants. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science,530(1), 74–96.

Pow, C. P. (2007). Securing the “civilised” enclaves: Gated communities and the moral geographies of exclusion in (Post-)socialist Shanghai. Urban Studies,44(8), 1539–1558.

Robinson, D. (2010). The neighbourhood effects of new immigration. Environment and Planning A,42(10), 2451–2466.

Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). Biometrika trust the central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects the central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika,70(1), 41–55.

Schneeweis, N. (2011). Educational institutions and the integration of migrants. Journal of Population Economics,24(4), 1281–1308.

Schwarzweller, H. K. (2006). Parental family ties and social integration of rural to urban migrants. Journal of Marriage and the Family,26(4), 410.

Shen, J. (2017). Stuck in the suburbs? Socio-spatial exclusion of migrants in Shanghai. Cities,60, 428–435.

Shubin, S., & Dickey, H. (2013). Integration and mobility of Eastern European migrants in Scotland. Environment and Planning A,45(12), 2959–2979.

State Council. (2014). National new urbanization planning. Retrieved March 16, 2014 from http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2014-03/16/content-2639841.htm.

Wang, M., Cheng, H., & Ning, Y. (2015). Social integration of migrants in Shanghai’s urban villages. Acta Geographica Sinica,70(8), 1243–1255.

Wang, W. W., & Fan, C. C. (2012). Migrant workers’ integration in urban China: Experiences in employment, social adaptation, and self-identity. Eurasian Geography and Economics,53(6), 731–749.

Wang, Z., Zhang, F., & Wu, F. (2016). Intergroup neighbouring in urban China: Implications for the social integration of migrants. Urban Studies,53(4), 651–668.

Wang, Z., Zhang, F., & Wu, F. (2017a). Neighbourhood cohesion under the influx of migrants in Shanghai. Environment and Planning A Economy and Space,49(2), 407–425.

Wang, Z., Zhang, F., & Wu, F. (2017b). Social trust between rural migrants and urban locals in China—Exploring the effects of residential diversity and neighbourhood deprivation. Population, Space and Place,23(1), 1–15.

Wei, L., & Gao, F. (2017). Social media, social integration and subjective well-being among new urban migrants in China. Telematics and Informatics,34, 786–796.

Wu, Q., Cheng, J., Chen, G., Hammel, D. J., & Wu, X. (2014). Socio-spatial differentiation and residential segregation in the Chinese city based on the 2000 community-level census data: A case study of the inner city of Nanjing. Cities,39, 109–119.

Wu, F., & He, S. (2005). Changes in traditional urban areas and impacts of urban redevelopment: A case study of three neighbourhoods in Nanjing, China. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie,96(1), 75–95.

Xie, S., & Chen, J. (2018). Beyond homeownership: Housing conditions, housing support and rural migrant urban settlement intentions in China. Cities,78, 76–86.

Yue, Z., Li, S., Jin, X., & Feldman, M. W. (2013). The role of social networks in the integration of Chinese rural-urban migrants: A migrant-resident tie perspective. Urban Studies,50(9), 1704–1723.

Zhu, Y., Breitung, W., & Li, S. (2012). The changing meaning of neighbourhood attachment in Chinese commodity housing estates: Evidence from Guangzhou. Urban Studies,49(11), 2439–2457.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for financial support from the NSFC-ESRC Joint Funding (NSF71661137004), National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSF71573166) and Graduate Student Innovation Funding of SHUFE (CXJJ-2017-404).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1: The PSM methods used in the study

Scholars define the propensity score as the conditional probability of a given set of observation covariates assigned to the treatment group (Rosenbaum and Rubin 1983).

In formula (2), X is the multidimensional eigenvector of the control group, and B is the core dependent variable, which equals 1 if migrants live in formal neighbourhoods and 0 otherwise. If we can get a propensity score, we can estimate the ATT by comparing the potential differences between the experimental and control groups as follows (Becker and Ichino 2002),

Here Y1i and Y0i respectively indicate the potential results of the experimental group and the control group. Following previous studies (Becker and Ichino 2002; Dehejia and Wahba 2002), we use the following Logit model to get the propensity score.

Here, X is the same as above. It is assumed to affect migrants’ tendency of living in different neighbourhoods. α is a coefficient vector. Then, we use three matching methods to estimate the ATT, i.e. Nearest neighbor matching, Radius matching and Kernel matching. The Nearest neighbor matching method is the most commonly used matching method. It finds the individual with the smallest difference of PS value in the control group with the experimental group as its comparison object, which can be represented as follows,

However, the Radius matching method is to set the radius beforehand, and to find all the control samples in the unit circle within the set radius range. The radius is positive. As the radius decreases, the matching requirements become more stringent. The formula is shown as follows,

In the above two formulas, C refers to the control group. We let T represent the experimental group, \({\text{Y}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{T}}\) and \({\text{Y}}_{\text{j}}^{\text{C}}\) respectively represent the observation results of the experimental group and the control group. Meanwhile, let the control group’s number matched with observation i ∈ T by \({\text{N}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{C}}\) and define the weights \({\text{w}}_{\text{ij}} = \frac{1}{{{\text{N}}_{\text{i}}^{\text{C}} }}\) if j ∈ C(i), otherwise, wij = 0. In addition, suppose that the experimental group has NT observations. We can estimate the ATT following (Becker and Ichino 2002).

Then, we use M as the matching method, \({\text{w}}_{\rm j} = \mathop \sum \limits_{\rm i} {\text{w}}_{\rm ij}\). Assuming that the weights remain unchanged, the validity of the neighborhood is independent. We can estimated the variance of τM as the following,

The third method (the Kernel matching method) is slightly different from the first two. It is to construct a virtual object to match the treatment group. The principle is to average the weight of the existing control variables, and the value of the weight is inversely related to the PS value difference between the treatment group and the control group. The ATT of this method is estimated as following:

In formula (9), G(·) means the Gaussian kernel function, and bandwidth parameter is hn.

It is a consistent estimate of Y0i with counterfactual results.

Appendix 2

See Tables 6, 7, 8, 9 and Fig. 3.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Zou, J., Chen, Y. & Chen, J. The complex relationship between neighbourhood types and migrants’ socio-economic integration: the case of urban China. J Hous and the Built Environ 35, 65–92 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-019-09670-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10901-019-09670-2