Abstract

People surviving cancer represent a particularly vulnerable population who are at a higher risk for food insecurity (FI) due to the adverse short- and long-term effects of cancer treatment. This analysis examines the influence of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence of FI among cancer survivors across New York State (NYS). Data from the 2019 and 2021 NYS Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) were used to estimate the prevalence of FI. Multivariable logistic regression was used to explore socioeconomic determinants of FI. Among cancer survivors, FI varied geographically with a higher prevalence in New York City compared to the rest of the state (ROS) prior to (25.3% vs. 13.8%; p = .0025) and during the pandemic (27.35% vs. 18.52%; p = 0.0206). In the adjusted logistic regression model, pre-pandemic FI was associated with non-White race (OR 2.30 [CI 1.16–4.56]), household income <$15,000 (OR 22.67 [CI 6.39–80.43]) or $15,000 to less than <$25,000 (OR 22.99 [CI 6.85–77.12]), and more co-morbidities (OR 1.39 [CI 1.09–1.77]). During the pandemic, the association of FI with non-White race (OR 1.76 [CI 0.98–3.16]) was attenuated but remained significant for low household income and more co-morbidities. FI was newly associated with being out of work for less than one year (OR 6.36 [CI 1.80–22.54] and having one (OR 4.42 [CI 1.77–11.07]) or two or more children in the household (OR 4.54 [CI 1.78–11.63]). Our findings highlight geographic inequities and key determinants of FI among cancer survivors that are amendable to correction by public health and social policies, for which several were momentarily implemented during the pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

As defined by the United States Department of Agriculture, food insecurity is a lack of consistent access to enough food for every person in a household to live an active, healthy life. This can be a temporary situation for a family or can last a long time. In 2019, the year that preceded the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) pandemic, an estimated 10.5% of US households (down from 11.1% in 2018) were food insecure at least sometime during the prior year [1]. Historically, rates of food insecurity have been higher than the national average for the following groups: households with incomes near or below the federal poverty level ($14,580 for a household size of 1) [2]; all households with children and particularly households with children headed by single women or single men; women and men living alone; Black- and Hispanic-headed households; and households in principal cities and nonmetropolitan areas. The prevalence of food insecurity also varies by state, ranging from 6.6% in New Hampshire to 15.7% in Mississippi in 2017–2019. Food insecurity rates across New York State (NYS) during this same 3-year period were similar to the national average (10.8%) [3].

The COVID-19 pandemic caused widespread economic hardships and disrupted food systems across the country, disproportionately impacting the most vulnerable populations, especially in states hardest hit by the pandemic, such as New York. People surviving cancer represent a particularly vulnerable population secondary to their higher oncological risk (recurrent or secondary cancer). Food insecurity may be more prevalent in cancer survivors due to the high cost of treatment, lost wages, unemployment, and increased burden placed on caregivers within the same household [4]. Additionally, among those with a cancer diagnosis, food insecurity has been associated with decreased adherence to cancer treatment, foregone medical care, increased mental health issues such as depression, and adverse physical health outcomes. To our knowledge, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food access has not been assessed among cancer survivors across NYS. Hence, this analysis is the first to (1) describe the prevalence of food insecurity amongst cancer survivors before (2019) and during the COVID pandemic (2021) across the state, as well as any geographic variability; (2) examine demographic and socioeconomic determinants associated with food insecurity among cancer survivors during both periods.

Methods

We used publicly available data from the NYS Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) for 2019 and 2021. BRFSS is sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and is an annual telephone survey administered by individual states to collect state-specific data on health-related risk behaviors, chronic health conditions, and the use of preventive services among the noninstitutionalized civilian population aged 18 years and older [5]. Interviews are conducted throughout the year in both English and Spanish and reach households with landline telephones or cell phones. The BRFSS allows for a sub-division of analysis to compare respondents residing in NYC (five boroughs combined) to residents in the rest of the state (ROS). The data within the BRFSS data set are neither identifiable nor private and thus do not meet the federal definition of “human subject” as defined in 45 CFR 46.102. Therefore, this study did not need to be reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board.

The 2021 annual NYS BRFSS was an expanded BRFSS [6] designed to support regional and county-level analysis, resulting in a larger sample size. The BRFSS uses a core set of questions and allows states to include additional questions to serve their specific needs [7]. Food security was a NYS-Added Module in the 2019 and 2021 BRFSS surveys. The module included the following question: How often in the past 12 months would you say you were worried or stressed about having enough money to buy nutritious meals? Would you say—always, usually, sometimes, rarely, never? Food insecure individuals were defined as respondents who indicated they were always, usually, or sometimes worried or stressed about having enough money to buy nutritious meals in the past 12 months. Cancer survivors were defined as respondents who indicated they were ever told by a doctor, nurse, or other health professionals that they had any type of cancer other than skin cancer. Respondents only reporting a skin cancer diagnosis were excluded as the survey does not distinguish between melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancers, and nonmelanoma skin cancer typically does not require treatment beyond surgery [8].

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 software (Cary, NC, USA). Considering the complex survey design of BRFSS, all statistical analyses incorporated stratification and weighting following the methodology established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [9, 10]. We computed unweighted and survey-weighted descriptive statistics to summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of respondents in 2019 and 2021 based on cancer survivorship status, then used SAS proc surveyfreq to perform survey-weighted chi-squared tests comparing characteristics among four cohorts: 2019 cancer survivors (A), 2019 respondents without cancer (B), 2021 cancer survivors (C), and 2021 respondents without cancer (D). We performed an additional survey-weighted chi-squared analysis in the subset of cancer survivors to compare the geographic distribution of food insecurity in the following four cohorts: 2019 NYC (A), 2019 ROS (B), 2021 NYC (C), and 2021 ROS (D). We then performed univariable logistic regression models using SAS proc surveylogistic to identify factors associated with food insecurity in 2019 and 2021. We chose the most scientifically and evidence-based relevant variables with a significance of p < 0.10 in the univariable models to include in multivariable models predicting food insecurity among cancer survivors in 2019 and 2021.

Covariates

The following covariates were included in the multivariable analyses: age (18–64, 65+), sex at birth (male, female), self-identified race (White, Others), education (less than high school, high school or higher), income (<$15,000, $15,000 to less than $25,000, $25,000 to less than $50,000, or $50,000 or more), employment status (employed for wages, self-employed, out of work less than 1 year, retired, or unemployed), marital status (married/member of an unmarried couple, widowed/divorced/separated, or never married), number of children (one child, two or more children, no children), health insurance (Medicaid, Medicare, private plan, other insurance, or no coverage) and total number of chronic health conditions (0–7). The chronic conditions included have been previously associated with an increased burden of food insecurity and include diabetes, myocardial infarction, angina/coronary heart disease, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, depressive disorder, or kidney disease [11,12,13,14,15].

Results

Respondents who did not answer the question regarding a cancer diagnosis were excluded from the analysis, resulting in 14,182 respondents in 2019 and 38,927 respondents in 2021. Tables 1 and 2 depict the characteristics of the respondents to the BRFSS survey in 2019 and 2021, stratified by those who met the criteria of being a cancer survivor versus those who never had a cancer diagnosis. In both years, cancer survivors were more often older (57.4% vs. 18.6%; 60.1% vs. 19.9% p < 0.0001), female (61.6% vs. 51.3%; 60.8% vs. 51.4% p < 0.0001), self-identified as white (70.9% vs. 54.4%; 75.9% vs. 55.0% p < 0.0001), disabled (41.1% vs. 24.8%; 41.8% vs. 25.4% p < 0.0001), retired (44.5% vs. 16.31%; 49.5% vs. 17.41% p < 0.0001), divorced/separated or widowed (31.0% vs. 17.2%; 31.4% and 17.1%; p < 0.0001), resided with no children in the household (86.4% vs. 63.9%; and 86.1% vs. 65.8% p < 0.0001), and had Medicare as their primary health insurance (43.5% vs. 16.2%; 49.7% vs. 19.1% p < 0.0001). Regarding cancer risk factors, cancer survivors were more often former smokers (38.4% vs. 22.4%; 37.6% vs. 19.9% p < 0.0001) and less physically active (32.3% vs. 26.8%; 32.1% vs. 25.3% p < 0.0001). They also self-reported a higher proportion of other chronic health conditions, including diabetes (19.5% vs. 11%; 20.5% vs. 11.9%; p < 0.0001), myocardial infarction (9.6% vs. 3.5%; 8.0% vs. 3.2%; p < 0.0001), angina/CHD (9.1% vs. 3.5%; 9.1% vs. 3.6% p < 0.0001), chronic obstructive lung disease (13.94% vs. 5.11%; 13.69% vs. 4.88% p < 0.0001), depression (18.2% vs. 15.1% p = 0.0308; 21% vs. 16.7%; p = 0.0010) and kidney disease (7.5% vs. 2.1%; 8.2% vs. 2.4%; p < 0.0001).

Prior to the COVID pandemic, the proportion of cancer survivors across the state experiencing food insecurity in comparison to respondents with no prior cancer diagnosis did not significantly differ (17.78% vs. 19.5%; p = 0.3716). However, food insecurity among cancer survivors varied geographically, with a higher prevalence in the five boroughs of NYC compared to the ROS (25.3% vs. 13.8%; p = 0025), as shown in Table 3. While food insecurity rates increased across the state because of the pandemic, the geographic difference among cancer survivors persisted (27.35% vs. 18.52%; p = 0.0206).

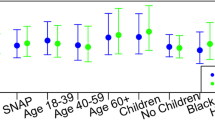

The multivariable survey-weighted logistic regression models predicting food insecurity among cancer survivors in both years are shown in Table 4. Pre-pandemic cancer survivors had higher odds of being food insecure if they self-identified as non-White race (Odds Ratio 2.30 [95% Confidence Interval, 1.16, 4.56], had a household income <$15,000 (22.67 [6.39, 80.43]) or $15,000 to less than <$25,000 (22.99 [6.85, 77.12]), and had more cumulative chronic health conditions (1.39 [1.09, 1.77]). During the pandemic, the odds of being food insecure among cancer survivors were attenuated for non-White race (1.76 [0.98–3.16]) but remained significant for those with a household income <$15,000 (15.25 [5.3–43.91]) or $15,000 to less than <$25,000 (OR 11.81 [4.80–29.06]) as well as those with more co-morbidities (1.56 [1.28, 1.90]). Cancer survivors out of work for less than one year (6.36 [1.80, 22.54) and those with children in the household (one child: 4.42 [1.77, 11.07]; two or more children; 4.54 [1.78, 11.63]) also had a higher odd of being food insecure. The odds of food insecurity were lower among cancer survivors with private health insurance (0.20 [0.06, 0.64]) compared to no health insurance.

Discussion

In this study, the prevalence of food insecurity even before the COVID-19 pandemic was disproportionally experienced by cancer survivors residing in NYC compared to the ROS. The burden of food insecurity amongst this vulnerable population exceeds the national average (11%) by almost twofold and is higher than the overall state average (24.9%) [16]. While other studies have reported a prevalence of food insecurity among cancer survivors in the range of 4.0–26.2%, we are unaware of any studies that have described a similar geographic inequity with urban areas outpacing more suburban or rural areas [17,18,19]. Among cancer survivors, the most significant determinant of food insecurity during both periods was an annual household income of less than $25,000. Our findings of low-income and non-White race as independent factors that increase the likelihood of being food insecure align with previous studies [20].

While the goal of this study was to assess whether cancer survivors experienced higher rates of food insecurity because of the pandemic, we instead observed an interesting attenuation of the disparity related to the social construct of race and ethnicity accompanied by a lowering of the odds based on household income. This finding may have occurred due to the increased availability of food assistance programs, unemployment insurance, and stimulus payments across NYS [21,22,23], especially in NYC as the pandemic’s epicenter. Evaluations of NYS policies demonstrate that food policy reforms gained significant momentum during the COVID-19 pandemic. More than 300 policy provisions were implemented across the State during the state of emergency (March 2020–June 2021). About two-thirds of the policies focused on supporting food businesses and workers, while the other third targeted ensuring adequate food access (32%) for needy communities [24]. These additional state programs layered on top of federal programs like the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation program may have buffered the most vulnerable populations. Evidence of social protection programs in other countries resulting in reductions in food insecurity because of the pandemic further demonstrates the capabilities of these programs to close critical gaps in food access created by social determinants such as poverty, race, and ethnicity [25,26,27,28].

During the pandemic, about 40% of cancer survivor survey respondents were of working age (18–64). While the overall percentage (2.84%) of cancer survivors in 2021 who reported they were out of work for less than a year was small, it represented a significant increase compared to the prevalence in 2019 (1.1%). Employed individuals diagnosed with cancer have a variety of postdiagnosis employment trajectories [29]. While some survivors may report their most significant limitations in the first year postdiagnosis, in at least one study, cancer survivors more than 11 years postdiagnosis reported nearly double the number of work absence days within the preceding year versus their colleagues with no cancer diagnosis [30]. Unfortunately, in 2019 and 2021, NYS did not include the optional module of years since the first cancer diagnosis. Thus, we were unable to factor that into the analysis. However, data from the 2020 BRFSS module demonstrates that about 43% of respondents in that year were diagnosed with cancer more than 10 years, 19% 6–10 years, 38% 5 years or less, and 18% were still actively undergoing treatment.

There are several study strengths and limitations to consider in the context of our findings. Strengths of the study include the use of survey data provided by the BRFSS, which provides population-based estimates of food insecurity that are generalizable to all NYS adults. Furthermore, the pre- and intra-pandemic data comparisons allow for further examination of secular trends in food insecurity. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine this trend in association with cancer. Most recently, Crossa et al., using data from the 2017–2018 NYC Community Health Survey, explored the associations between food insufficiency, a more severe form of food insecurity, and the chronic health conditions of hypertension, diabetes, obesity, and depression [31]. Food insufficiency was associated with a higher odd for all chronic health conditions except obesity. Similarly, they found geographic inequities regarding the neighborhoods with the highest prevalence of food insufficiency being those areas with the “greatest social and economic inequities associated with the legacy of structural racism.” As recent findings have demonstrated that the Bronx has the highest rate of food insecurity (39%) in the state our findings of geographic inequities of food insecurity among cancer survivors across the state is not surprising.

Lastly, the sample size of the BRFSS permitted more nuanced examination of food insecurity patterns across social and demographic characteristics, as well as geography, yielding novel insights in subgroups that are at increased risk for experiencing food insecurity and its sequelae. Unfortunately, given the cross-sectional nature of the BRFSS, we are unable to examine the persistence of food insecurity within NYS households over time, or the trajectory of cancer patients’ illness. Furthermore, we are unable to ascertain the impacts of food insecurity on chronic disease prevention or management, including among cancer survivors, which may have clinical implications for individuals living with cancer. More longitudinal data is needed to fully elucidate the associations and pathways between food insecurity and health status, including poor diet quality, adverse mental health outcomes, or avoidance of medical treatment or medication adherence due to cost.

In light of the Biden Administration’s commitment coming out of the White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health to Ending Hunger and Reducing Diet-Related Diseases and Disparities, continued research highlighting the deleterious effects of food insecurity on cancer risk, early detection, and cancer treatment response and outcomes, as well as on interventions to address food insecurity, are warranted [32]. Research is currently being conducted on the effectiveness of monthly unconditional guaranteed income for people with cancer and its impact on food insecurity and cancer outcomes [33]. Within NYC, interventions to address food insecurity through vouchers and linkages to food pantries have shown promise in improving cancer treatment completion [34]. NYC has also taken steps to institutionalize long-term food systems planning through the 10-year food policy plan, “Food Forward NYC,” mandated by local law LL 2020/040. The plan outlines five strategic areas for developing future food policy around food access and food security, food economy and good jobs, supply chains and regional infrastructure, environmental sustainability, and food system knowledge and governance [35].

Implementing ongoing, embedded food insecurity screening across all cancer care sites, at an evidence-based cadence to be determined, could serve as a cancer and food insecurity surveillance system and an indicator of the impact of food insecurity policies, which could be an essential policy intervention. This should be coupled with community-engaged interventions and advocacy for upstream policy approaches, including food voucher systems for low-income individuals, potentially coupled with Medicaid and Emergency Medicaid enrollment, to ensure progress toward addressing health inequities across the cancer continuum.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available by request to the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Data New York State Department of Health Bureau of Chronic Disease Evaluation and Research. The data analysis code used for analysis is available by contacting the corresponding author.

References

Coleman-Jensen, A., Rabbitt, M. P., Gregory, C. A., & Singh, A. (2021). Household food security in the United States in 2020, ERR-298.

Poverty Guidelines. (2023). Retrieved November 27, 2023, from https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines

Rabbitt, M. P., Hales, L. J., Burke, M. P., & Coleman-Jensen, A. (2023). Household food security in the United States in 2022.

Simmons, L. A., Modesitt, S. C., Brody, A. C., & Leggin, A. B. (2006). Food insecurity among cancer patients in Kentucky: A pilot study. Journal of Oncology Practice, 2(6), 274–279. https://doi.org/10.1200/jop.2006.2.6.274

Center for Disease Prevention and Control. (2022). BRFSS prevalence & trends data. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Center for Disease Prevention and Control.

Expanded Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (Expanded BRFSS). Retrieved November 27, 2023, from https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/brfss/expanded/

New York State Department of Health. Retrieved from https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/brfss/expanded/

New York State Department of Health. Retrieved from https://www.health.ny.gov/statistics/brfss/reports/docs/survivorship_compendium_2018.pdf

Complex Sampling Weights and Preparing 2021 BRFSS Module Data for Analysis. (2022). Retrieved November 27, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2021/pdf/Complex-Sampling-Weights-and-Preparing-Module-Data-for-Analysis-2021-508.pdf

Complex Sampling Weights and Preparing 2019 BRFSS Module Data for Analysis. (2020). Retrieved November 27, 2023, from https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/2019/pdf/complex-smple-weights-prep-module-data-analysis-2019-508.pdf

Cai, J., & Bidulescu, A. (2023). The association between chronic conditions, COVID-19 infection, and food insecurity among the older US adults: Findings from the 2020–2021 National Health Interview Survey. BMC Public Health, 23, 179. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15061-8

Camacho-Rivera, M., Albury, J., Chen, K., Ye, Z., & Islam, J. Y. (2022). Burden of food insecurity and mental health symptoms among adults with cardiometabolic conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610077

Ni, K., Wan, Y., & Zheng, Y. (2023). Association between adult food insecurity and self-reported asthma in the United States: NHANES 2003–2018. Journal of Asthma, 60(11), 2074–2082. https://doi.org/10.1080/02770903.2023.2214921

Seligman, H. K., Bindman, A. B., Vittinghoff, E., Kanaya, A. M., & Kushel, M. B. (2007). Food insecurity is associated with diabetes mellitus: Results from the National Health Examination and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 1999–2002. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 22(7), 1018–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0192-6

Seligman, Hilary K., Laraia, Barbara A., & Kushel, Margot B. (2011). ERRATUM: Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants 1, 2. Journal of Nutrition, 140(2), 304–310. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.109.112573

Self-Reported Food Insecurity Among New York State Adults by County, BRFSS 2021: 2023.

Beavis, A. L., Sanneh, A., Stone, R. L., Vitale, M., Levinson, K., Rositch, A. F., Fader, A. N., Topel, K., Abing, A., & Wethington, S. L. (2020). Basic social resource needs screening in the gynecologic oncology clinic: A quality improvement initiative. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 223(5), 735.e1-735.e14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.05.028

Byker Shanks, C., Andress, L., Hardison-Moody, A., Jilcott Pitts, S., Patton-Lopez, M., Prewitt, T. E., Dupuis, V., Wong, K., Kirk-Epstein, M., Engelhard, E., Hake, M., Osborne, I., Hoff, C., & Haynes-Maslow, L. (2022). Food insecurity in the rural United States: An examination of struggles and coping mechanisms to feed a family among households with a low-income. Nutrients, 14(24), 5250. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14245250

Poghosyan, H., & Scarpino, S. V. (2019). Food insecure cancer survivors continue to smoke after their diagnosis despite not having enough to eat: Implications for policy and clinical interventions. Cancer Causes and Control, 30(3), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-019-01137-7

Robien, K., Clausen, M., Sullo, E., Ford, Y. R., Griffith, K. A., Le, D., Wickersham, K. E., & Wallington, S. F. (2023). Prevalence of food insecurity among cancer survivors in the United States: A scoping review. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, 123(2), 330–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jand.2022.07.004

Kumar, S. L., Calvo-Friedman, A., Freeman, A. L., Fazio, D., Johnson, A. K., Seiferth, F., Clapp, J., Davis, N. J., & Schretzman, M. (2023). An unconditional cash transfer program for low-income New Yorkers affected by COVID-19. Journal of Urban Health, 100(1), 16–28.

Morita, S. X., & Kato, H. (2023). Racial disparity and trend of food scarcity amid COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Cureus. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.33232

Winkler, L., Goodell, T., Nizamuddin, S., Blumenthal, S., & Atalan-Helicke, N. (2023). The COVID-19 pandemic and food assistance organizations’ responses in New York’s Capital District. Agriculture and Human Values, 40(3), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-022-10400-8

Ilieva, R. T., Fraser, K. T., & Cohen, N. (2023). From multiple streams to a torrent: A case study of food policymaking and innovations in New York during the COVID-19 emergency. Cities, 136, 104222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2023.104222

Parliament of Australia. (2022). Australian Government COVID-19 Disaster Payments: A quick guide.

Béland, D., Dinan, S., Rocco, P., & Waddan, A. (2021). Social policy responses to COVID-19 in Canada and the United States: Explaining policy variations between two liberal welfare state regimes. Social Policy and Administration, 55, 280–294.

Lustig, N., & Trasberg, M. (2021). How Brazil and Mexico diverged on social protection in the pandemic. Current History, 120(823), 57–63.

Palma, J., & Araos, C. (2021). Household coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic in Chile. Frontiers in Sociology., 6, 728095. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2021.728095

Nekhlyudov, L., Walker, R., Ziebell, R., Rabin, B., Nutt, S., & Chubak, J. (2016). Cancer survivors’ experiences with insurance, finances, and employment: Results from a multisite study. Journal of Cancer Survivorship, 10(6), 1104–1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11764-016-0554-3

Yabroff, K. R., Lawrence, W. F., Clauser, S., Davis, W. W., & Brown, M. L. (2004). Burden of illness in cancer survivors: Findings from a population-based national sample. Journal of the National Cancer Institute, 96(17), 1322–30. https://doi.org/10.1093/jnci/djh255

Crossa, A., Leon, S., Prasad, D., & Baquero, M. C. (2024). Associations between food insufficiency and health conditions among New York city adults, 2017–2018. Journal of Community Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-023-01296-4

Maino Vieytes, C. A., Zhu, R., Gany, F., Burton-Obanla, A., & Arthur, A. E. (2022). Empirical dietary patterns associated with food insecurity in U.S. cancer survivors: NHANES 1999–2018. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14062. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114062

Doherty, M., Heintz, J., Leader, A., Wittenberg, D., Ben-Shalom, Y., Jacoby, J., Castro, A., & West, S. (2023). Guaranteed Income and Financial Treatment (G.I.F.T.): A 12-month, randomized controlled trial to compare the effectiveness of monthly unconditional cash transfers to treatment as usual in reducing financial toxicity in people with cancer who have low incomes. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1179320. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1179320

Gany, F., Melnic, I., Wu, M., Li, Y., Finik, J., Ramirez, J., Blinder, V., Kemeny, M., Guevara, E., Hwang, C., & Leng, J. (2022). Food to overcome outcomes disparities: A randomized controlled trial of food insecurity interventions to improve cancer outcomes. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 40(31), 3603–3612. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.21.02400

(2022). Food forward NYC: A 10 year food plan. Retrieved April 15, 2024, from https://www.nyc.gov/site/foodpolicy/reports-and-data/food-forward.page

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the larger membership of the New York Cancer Consortiums Healthy Eating and Active Living (HEAL) Action Team. Collectively the action team aims to reduce the burden of obesity-associated cancers in at-risk groups across the state by addressing structural determinants, such as food insecurity, that hinder healthy lifestyle behaviors.

Funding

Drs. Marlene Camacho-Rivera and Erica Phillips efforts are supported in part by National Cancer Institute 1U54CA280808.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no potential conflicts of interests in regard to the authors of this manuscript and any funding sources for the study.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Camacho-Rivera, M., Haile, K., Pareek, E. et al. The Influence of the COVID 19 Pandemic on Food Insecurity Among Cancer Survivors Across New York State. J Community Health (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-024-01358-1

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-024-01358-1