Abstract

There has been a dearth of reports that examine the effect of immigration status on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. While intention to be vaccinated has been higher among adults in immigrant families than non-immigrant adults, uptake of the vaccine has been lower among immigrants and especially those who are undocumented. Concerns raised by immigrants usually centered on the lack of access to information, language barriers, conflicts between work and clinic hours, and fears over their precarious status in the U.S. To perform a rapid review, our time frame was December 2020 through August 2021. Our search strategy used the PUBMED and Google search engines with a prescribed set of definitions and search terms for two reasons: there were limited peer-reviewed studies during the early period of roll-out and real-time perspectives were crucially needed. Strategies used to promote equity include the use of trusted leaders as well as direct communication styles. Other strategies centered informational messaging from government agencies and the medical community, with a strong emphasis on coalescing broad engagement of the community and being responsive to language and cultural needs. In addition to communication and messaging to educate about COVID-19 vaccines, another important aspect of COVID-19 vaccine uptake was overcoming multiple obstacles that affect ease of access. This report suggests that vaccine uptake, and more generally pandemic response, in vulnerable communities may be better able to launch when they build on existing, trusted, culturally intelligent community-based organizations and local sociocultural processes. These organizations need continued support to contribute to population health equity in emerging health crises.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There has been a scarcity of reports that have examined the influence of immigration status on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake. The Urban Institute, using a sample from California, investigated differences in intention to receive a COVID-19 vaccination between adults in families with people in a household who were foreign born versus adults not living in immigrant families [1]. They found that adults in immigrant families reported a greater intention to be vaccinated than non-immigrant adults (75% vs 68%, respectively). However, immigrant families were more likely to report that their regular source of healthcare was a clinic or health center rather than a doctor’s office. This may be related to a higher rate of insurance in adults in immigrant families. Immigrant families noted difficulties with accessing information about COVID-19 vaccines, language barriers, and clashes between work and vaccine administration hours.

Issues raised by immigrants were commonly about the lack of access to information and fears over their precarious status in the U.S. For example, various undocumented residents were concerned about being questioned for official identification (ID) and documentation of insurance information that they might not have or they supposed would be used to contact immigration officials. For example, some feared that the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and U.S. Customs and Border Protection might be waiting for them at a vaccine administration site [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. In addition, the Trump Administration’s redefinition of “public charge,” which certified that use of public assistance services might be a sufficient foundation for deportation, was a worry for many non-citizens as they feared that accepting the vaccine would be included in this definition of a public charge [2, 5, 9,10,11]. Many immigrants were concerned about the cost of receiving a vaccine despite the vaccine and its administration being free. Another concern was around being able to stay employed if they might miss work due to possible side effects [3, 6, 11] Theories concerning the vaccine possibly causing DNA alteration that might amount to forced sterilization circulated among migrant Latinx communities [3, 7, 12].

As of May 2021, undocumented immigrants were less likely than documented persons to have been vaccinated against COVID-19, and their rate was half of what had been reported for the US general population at that time [13]. From these perspectives, intervention strategies are needed to increase COVID-19 vaccine uptake among documented and undocumented immigrants.

Methods

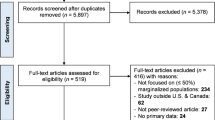

To perform a modified rapid review [14], our search strategy used PubMed, Google and the New York Times with a prescribed set of definitions and search terms for two reasons: there were limited peer-reviewed studies during the early period of vaccine roll-out and real-time perspectives were crucially needed in order to inform public health responses to an active pandemic emergency. The search terms consisted of three parts. The first part was “COVID-19 vaccine.” The second was “immigrant” OR “undocumented” OR “refugee.” The final part was “community” OR “access” OR “collaboration” OR “outreach.” The literature search was conducted in July and August 2021 and included articles from December 2020 through August 2021. The first author (JD) did the initial search and two others (SM and DV) shared duties validating the search process and results. The results were organized into two sections: (1) Trusted Communication and (2) Vaccine Access Support. Within each section, the order was a summary of expert opinion, descriptions of the implemented strategies without that did not have evaluation components, and then strategies with any implementation results.

Results

A total of 383 articles were identified and screened across all three search engines (PubMed, Google, and The New York Times). For PubMed, 20 articles were screened, and three were included. For Google, 350 were screened, and 44 were included. For The New York Times, 13 articles were screened, and 2 were included. Of the 49 total articles included in this review, 14 were either recommendations or expert opinion, and 43 described interventions (the number here is greater than the total articles reviewed because some articles provided both recommendations and an intervention description). Articles were removed from both Google and PubMed lists for several reasons, i.e., they did not describe or provide information on vaccine interventions specific to immigrant communities. For example, studies that reported immigration as a factor (with no further analysis), studies on hesitancy, news articles that had one line on immigration communities, or re-postings of the same article on different platforms. There were also many irrelevant articles/studies that were not on-topic, but would show up because of certain trigger words in their titles and headlines.

Trusted Communication

Expert Opinion and Recommendations

Undocumented immigrants shared concerns about the vaccine beyond its effectiveness. Fears of ICE, complications with immigration, and confusion on eligibility affected the intention and accessibility for many undocumented immigrants, refugees, and other people with precarious immigration status. City and state public health departments should communicate with agencies that frequently work with immigrant communities and have the capacity to deliver messages in multiple languages [15, 16]. Community leaders may translate culturally appropriate materials as trusted messengers through their characteristic understanding of their own communities and shared ethnic or cultural identities [17,18,19]. It is important that these messages are communicated sensitively and respectfully considering that many migrants have fears of immigration consequences, that vaccine side effects will be debilitating, and that they may not be able to work [1, 17]. Thus, messengers should be skilled in outreach to immigrant communities and in communication to discuss the benefits of the vaccine for those with who are unable to obtain accessible health information [20]. Training or coaching could be provided by local immigrant-serving agencies to build the local skills capacity for this type of service. An alternative to individual messengers would be a formal community advisory board who can direct health departments on how to engage various immigrant communities [19].

There must be clear information on the vaccine itself, the personal health information required to be vaccinated, the use of this data and who governs it, and any possible consequences of COVID-19 vaccination [15, 17]. There are several critical points encompassed by this recommendation, such as the fact that the vaccine is free, eligibility does not depend on residency or citizenship status, vaccinations are not included in the definition of a public charge, and vaccination data will not be shared with other agencies or organizations including ICE [1, 17, 18, 20].

There are various recommended delivery methods for vaccine promotion. While most recommendations focused on Spanish-speaking immigrants, this could be applied to other immigrant communities. For instance, copying other health promotion programs, COVID-19 vaccine uptake is suggested to benefit from traditional outreach through television programming, radio networking, and billboard ads in combination with known celebrities [19, 20]. Presentations at unions or churches can provide a platform for migrants to ask questions about the healthcare system, engage people who do not use technology, and assist those who do not access information in English [20]. In addition, vaccine education forums and online talks can provide information for those whose working schedule does not allow flexibility to visit clinics during daytime business operating hours [20].

Government Officials

Eight articles included messaging from key government agencies and officials. They clarified key points that many immigration advocates requested. Most of the messages centered on clarifying logistics to access vaccines and discrediting misinformation.

The changed definition of a public charge under President Trump encompassed several services that could affect an official immigration application. President Biden along with numerous federal and state governments explained that vaccination did not influence immigration [21,22,23,24,25,26].

Conversely, they also provided messages that clarified that COVID-19 vaccine eligibility was independent of immigration status [21,22,23,24,25,26]. Furthermore, another fear among those with precarious immigration statuses concerned the possibility of deportation by ICE at healthcare facilities. Department of Homeland Security repeated the policy that prevents ICE from conducting immigration operations in healthcare spaces [24]. President Biden interviewed with UniVision, a popular Spanish-language television network, to deliver this information to the many immigrants who are also Spanish-speaking, including some Latinx communities [22]. The state governments of Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, and Delaware amplified this message on their own websites [21, 25,26,27].

In addition, the lack of medical insurance for many migrants dissuaded them from receiving the vaccine. Several state governments emphasized on their websites that the vaccines were free. [21, 25,26,27] This directive can doubly target vaccine providers to promote the ways that they can be reimbursed if vaccines are provided to people who do not have Medicaid or a social security number (SSN) [28]. In a similar vein, many migrants may not have government-issued identification or fear the potential consequences of providing their personal health information. Many states and municipal government websites outlined, in multiple languages, the information required to receive the vaccine and how any data collected from a patient would be used [21, 25,26,27,28].

Non-Governmental Associations, Agencies, and Organizations

Seven articles demonstrated how health agencies and community-serving organizations are amplifying the messages from government officials. These include legal advocacy agencies, health associations, and state-specific migrant organizations.

Similar to governmental bodies, they clarified that the vaccine is free for anyone in the U.S., regardless of insurance status [29,30,31,32,33,34]. Some provided details on the efficacy of the vaccine, with comparisons of the health impact of COVID-19 for vaccinated individuals versus unvaccinated individuals [29, 31]. This was implemented to highlight the significance and relevance of the vaccine for the many immigrant workers that are employed in dense working areas or use public transportation. GoodRX included locators to nearest vaccination sites or linkages to state websites that outline the vaccine eligibility status; users could filter maps by details including vaccine brand and state [29].

A strong emphasis was placed on dispelling myths that suggest that the vaccine affects immigration. As before with the government officials, they explained that the vaccine has no effect on citizenship status, applications for citizenship, or residency [29,30,31,32,33,34]. The legal advocacy agency, Nolo, developed messages that prepared immigrants on the type of information that they may be asked at a vaccination site [30]. This support can avoid issues within the clinical setting as migrants are asked for some information. They also provided specific guidance on how to confront inappropriate legal questions by clinical staff, access legal aid, and report discrimination based on immigration status at vaccine sites [30]. On the other hand, health agencies such as NHW Community Health Center in Phoenix, Arizona trained their staff specifically to not ask about health insurance and immigration status to prevent access barriers for migrants [35]. This is a strong example of how leadership at health agencies can communicate these messages to show an organization’s commitment. As a whole, most organizations in Phoenix were able to explain that the data is only used for public health purposes [29,30,31,32,33,34].

Population-Specific Focused Education

Six articles included information on agencies that have introduced convenient and accessible education to many immigrant communities. Educational forums and outreach could be led by various players. It is essential to leverage important and trusted stakeholders at this stage; this may be physicians or other healthcare professionals, local or state government officials, trusted media outlets, and community leaders. They can speak directly to immigrant communities to discuss information regarding the vaccine. The interventions identified in this review were led by health departments, hospital-based networks, community health agencies, faith-based charities, immigrant-focused organizations, and farmworker foundations [35,36,37,38,39,40,41]. These agencies should be aligned with the demographics of their local immigrant communities, as language access must not be limited to Spanish only. Many initiatives had information available in Somali, Arabic, French, Simplified Chinese, Vietnamese, Lingala, Swahili, Tigrinya, and several other languages [36, 39, 40].

Importantly, the U.S.’ immigrant population has been exposed to medical systems in uniquely different ways, each with their own histories that may inhibit vaccine uptake. An African global health expert specifically recalled the involvement of Western countries, including the U.S. government, in unethical pharmaceutical clinical trials as recent as 1996 [39]. This led the African Family Holistic Health Organization to specifically include safety and efficacy information in their outreach. Moreover, many agencies addressed the numerous questions that migrants have on vaccine eligibility, accessible locations, registration requirements and processes, and other logistical details [36,37,38, 40].

Town Halls and Social Media

The rise in virtual communication lends itself to communicating with migrants who may not be able to drive to a town hall, have dependents, or are otherwise affected by accessibility issues. Zoom and WhatsApp have particularly been important for COVID-19 vaccine communication with immigrant communities. Multiple bilingual staff members at local immigration agencies may host physicians on platforms similar to Maine Health’s “Ask the Doc” town hall meetings; participants can invite family members who live in other countries as well [38]. Some communities may have their own niche communication applications. For instance, Asian Americans United specifically used WeChat to promote vaccines to Chinese American communities in Mandarin and the Fuzhou dialect [40].

However, only having an online presence can present severe limitations for immigrants who are not technologically experienced or have limited access. The distribution of physical flyers or pamphlets in high-contact areas provides an alternative outreach method. Community members were able to find vaccine promotion materials in local Portland businesses with language-specific posters available in stores that are popular among a specific immigrant demographic [38]. While not possible in all regions, one-on-one meetings were made available on these posters with relevant contact information.

Specific data was available for two interventions in Maine. On March 28, 2021, the Press Herald interviewed the director of the Maine Center for Disease Control, Dr. Nirav Shah, who answered questions on a vaccination initiative with the Unified Asian Communities.[38, 42] Over 40 people were reported as participants. Furthermore, they reported that the Northern Light Home Care & Hospice provided over 60 vaccines to non-English speakers using their public housing clinics and had scheduled almost 100 appointments through the Maine Access Immigrant Network.

Phone Lines

Five (5) articles provided an overview on telephone lines that were created specifically to increase vaccine uptake with immigrant communities. The strong reliance on online communication can limit immigrants’ ability to engage with health information and automated vaccine appointment-making. This can be developed by healthcare agencies such as Washington D.C.’s La Clinica, community agencies including Texan Dia de la Mujer Latina or Baltimore’s La Esperanza Centre, and ICE facilities in various states [43,44,45,46]. These centers that host phone lines can act as a liaison between states, vaccine providers, and immigrant populations. Indeed, the use of community health center clinical staff may reduce redundancy in creating new vaccine sites, as they are already established as access points for immigrants [44, 45].

While there are various ways to run a hotline or integrate it into existing structures, most phone services allow migrants to book vaccine appointments, talk directly to health professionals to ask health-related questions, and speak with local community leaders about specific fears or concerns [44,45,46,47]. In addition, those detained in ICE detention centers have extremely limited access to health information or community knowledge keepers. Californian-based health professionals launched a hotline that is specifically for people who are detained in the Yuba County Jail, Golden State Annex and the Mesa Verde ICE Processing [43]. These phone lines were staffed by people who could speak multiple languages contextualized to the local language demographic [44,45,46]. Some of the community members were able to use their own personal networks through religious affiliations, cultural affinities, and neighborhood communities [46].

Data available through Houston Public Media on February 12, 2021 indicated that the vaccine waitlist for Harris County Texas had over 308,000 people signed up through their website and phone-line [45]. Their telephone hotline was responsible for 45,000 of these people. From this total, 10,000 people spoke Spanish.

Promotors

Six articles expressed the use of community messengers to promote the COVID-19 vaccine. These initiatives were usually led by Latinx-serving organizations, who dubbed the community messengers as ‘promotores’ or ‘promotoras’. This is largely an effort that is used by immigrant-serving organizations or community member-led initiatives. Examples include CASA in three Northeastern states, the Hispanic Resource Centre in Virginia, a multi-organizational program in Chicago, and two different grassroots efforts by individuals in Iowa and Massachusetts [44, 48,49,50,51,52]. In fact, some of these programs were only possible through funding provided by local and state public health departments [50, 51]. The funds to community service organizations increased promotor capacity and supported important multi-sectoral relationships with the immigrant-serving agencies. Otherwise, local hospitals can still partner with these organizations to amplify up-to-date information on vaccine availability and eligibility [51, 52].

These promotors provided general outreach within immigrant communities with the aim to increase awareness on the COVID-19 vaccines [35, 44, 48,49,50,51,52]. This included promoting the benefits by dispelling myths or communicating local vaccine guidelines and eligibility. Other priority messages include the DHS statement that explained how ICE will not be present at vaccine sites, or that the vaccine is free for everyone, including those who do not have insurance. Multilingual promotors created accessible materials that support vaccine promotion messaging through multi-media information campaigns. In addition, they were available to answer questions on vaccine efficacy or logistical concerns on eligibility or accessibility. Since this information can become technical, it was critical that they were able to verbally communicate in Spanish or other languages that the local migrant communites speak. This ability was leveraged to schedule appointments for community members who are not able to use a computer or understand English. Promoters were also enlisted to remind community members of their second dose appointments, providing transportation to access the clinics, and accompanying people to their vaccination appointments for comfort and support.

Promotors disseminated information through their nuanced understanding of local migrant contexts. They had direct connections with local faith, business, and social service institutions, allowing them to attend mass at churches, distribute flyers that provide information in multiple languages, engage Latinx grocery stores with a high Hispanic population and other popularly trafficked public spaces [50, 51]. These locations (e.g., laundromats, community organizations, churches, or local businesses) were sometimes used to host drop-in information sessions virtually or physically [50, 51]. Promotors were trusted to canvas neighborhoods and physically knock on the doors of community members to directly advocate for COVID-19 vaccines [44]. Alternative spaces for promotors’ voices to be amplified were on local community television programs that are popular among migrants or radio station networks with large migrant audiences [35].

The data provided in some reports elucidated the impact of promotors on vaccine uptake and its related factors. In February, 13 News Now reported on the Hispanic Resource Centre’s (HRC) outreach in local Latinx and migrant communities [52]. Supported by the Baltimore City Health Department and the Mayor’s Office of Immigration Affairs, this partnership was between the HRC, Sentara Norfolk General Hospital, and the Chesapeake Regional Medical Center. The promotores were able to support registration of community members for vaccine appointments. By February 16, 2021, they had registered over 1000 people, vaccinated 266 people, and scheduled 130 people for the next day. Moreover, a month later, South Side Weekly interviewed a member of the Resurrection Project on their promotion efforts [51]. They serve a large population of immigrants in the south-side Chicago neighborhood of Pilsen. After partnering with St. Agnes of Bohemia Catholic Church and Saint Anthony Hospital, promotors were able to make appointments for immigrant residents during an event on March 25, 2021. All promotors were bilingual and called local community members to discuss the vaccines. This includes vaccine safety and eligibility, ICE presence, and supports to attend vaccination appointments. This event had been replicated 10 more times, helping 331 people in one day during a physical vaccine promotion event. People lined up 3 h before the event began. Furthermore, in May, the Ames Tribune reported on the vaccine outreach efforts at St. Cecelia Catholic Church [50]. Many people in the congregation are Spanish-speaking Latinx immigrants. An individual parishoner promoted herself as a person who can discuss the vaccine at mass one week. Speaking Spanish and English, she was able to talk to over 250 people by herself. She personally knew 47 people who were vaccinated after her discussions. After receiving support from the COVID-19 Emergency Fund for Story County Immigrants, she was able to help over 80 people receive their vaccinations.

Vaccine Access Support

Recommendations and Expert Opinion

States must create vaccine distribution sites that are geographically accessible, accommodates various shift schedules including people who work evenings and weekends, and do not have access to any online promotion [16, 17]. Possible sites could be community fairs, public schools, faith-based institutions, or mobile vaccine clinics that are directly in areas with high immigrant populations [16]. As adults in Californian immigrant families depend on community clinics, it is advisable to center these agencies to provide vaccines to immigrant communities [1].

Immigrant peoples should be able to drive into the sites directly or walk-up immediately to serve the large number of immigrant families whose preferences for receiving healthcare services are not aligned with the general structure of the American healthcare system [15, 17]. Vaccine-providing health agencies should limit the information required for vaccinations, including SSN, residency documentation, and other identification documents that many migrants either may not have or may be reluctant to disclose [53]. As migrants may be travelling between states often, it is recommended to provide single dose vaccines when possible with portable, paper copies of immunization records [54].

Lastly, ICE should have vaccine doses procured directly from the federal government to avoid bureaucratic delays with states [55,56,57]—they can employ the same community messengers that are used by health agencies in the surrounding areas of ICE facilities.

Pop-Up Clinics

Eight articles provided evidence of pop-up clinics that specifically targeted immigrants, including those who were undocumented. They were hosted largely by a mixture of community health centers and public health departments.

Vaccine clinical sites included local, familiar sites such as libraries, schools, consulates, and local primary care centers [51, 58,59,60,61]. Clinical staff spoke multiple languages or had translators and interpreters available. Workers were available to process registrations through the phone for patients to request accommodations, disclose specific needs or fears, and generally discuss the vaccine [50, 51, 59,60,61]. Translators had multiple purposes—they allowed immigrants to communicate with clinical staff during their vaccine appointment and they provided comfort by accompanying people as they move through the clinic. To reduce access barriers for immigrants with limited information or awareness, these pop-up events were either walk-ins with no appointments required or involved prior registrations supported through strong outreach campaigns. Some health agencies like Story Medical offered transportation assistance through partnerships with the mobile-app based ride sharing companies Uber and Lyft [50].

Local immigrant serving agencies partnered with healthcare agencies, employment associations and unions, and legal advocacy groups [40, 51, 58, 59, 61]. The purpose of these partnerships served to merge their collective social media presences, webpages, and client base and amplify the knowledge and awareness of these pop-up clinics. A unique way that some institutions engaged these community agencies was by specifically reserving appointments for immigrant community members or people who have been registered through specific programs, initiatives, or organizations [59, 61]. Since these organizations were the first point of contact for most migrants, some provided guidance on the state policies that determine eligibility for vaccines and encouraged migrants to report whenever they were asked for proof of residency in areas where this proof was not required [58].

On March 12, 2021, the Philadelphia Department of Health coordinated a partnership between local Sunray Pharmacy and immigrant service organizations, including SEAMAAC (one of the oldest and largest refugee-founded agencies), New Sanctuary Movement, Africom, HIAS, Juntos, Asian Americans United [40, 43]. These appointments required registration that was restricted to immigrant residents only, as well as ensuring that these residents met the state eligibility criteria. They vaccinated 200 people for their first Pfizer dose through this effort.

Two days later, an article reported on Building One Community in Stamford, Connecticut, which is an immigrant support agency that hosted a vaccination clinic [61]. These registrations were required prior to the clinic date. Many community members were from Latinx and Montenegrin ethnicities. Immigrants who were over the age of 55 and met the vaccine eligibility at the time, were able to book over 300 appointments. Building One was chosen for funding because of its established connection with immigrant community members and were able to use residents’ emails, phone numbers, and knowledge of popular areas where immigrants are available. They partnered with the state-wide primary care provider, Community Health Centre Inc., and employment agencies like Service Employees International Union, and Local 32BJ for outreach.

The Brazilian Worker Center is based in Boston, Massachusetts, and serves Brazilians across the state [60]. It partnered with the Lawyers for Civil Rights for legal support and outreach and with Whittier Street Health Center who already provides primary care services for immigrant communities. On April 2, 2021, they were able to provide over 200 vaccinations. As of April 10, 2021, there were 2,500 on their vaccination waiting list. Later in the month, Guatemalan-Maya Centre vaccinated over 700 people on April 24, 2021 in Lake Worth Florida [58]. They overruled the residency requirements in Florida in agreement with other local advocacy groups—there had not been any consequences to forgoing the policy. The migrant-serving agencies verified people’s identities or proof of address through letters of support, membership cards, and other identification separate from state or federal government.

Summary

The population groups most heavily affected by COVID-19 each require tailored interventions that address group-specific concerns [62]. For undocumented immigrants, this review highlights that the prominent issues around low vaccine uptake were less frequently attributed to medical mistrust which elsewhere in the literature was more often discussed as prominent for non-immigrant Black communities. Immigrant concerns were more frequently presented as access issues. Those issues include concern about lack of insurance, possible identification as undocumented status that could be reported to ICE resulting in deportation, and lost wages for the time needed to get the vaccine or recover from possible side effects. Despite the differences between identity groups on factors that can inhibit vaccine uptake, there are several notable similarities for elements that are recognized as important to increase COVID-19 vaccination. These similarities include the use of trusted leaders as well as direct communication styles, messaging from government agencies and the medical community, but most importantly, broad engagement of the community, all while being mindful of language needs and cultural considerations. In additional to communication and messaging to educate about COVID-19 vaccines, another important aspect of COVID-19 vaccine uptake is ease of access. This includes convenient locations, flexible timing, and staff attuned to the needs of the patients they serve. The San Francisco academic, health department and an established community-based organization’s collaboration [63] provides the most developed report on outreach that addresses both COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and access for undocumented immigrants. This report demonstrates that vaccine uptake, and more generally pandemic response, in marginalized communities may be better able to launch when they build on existing, trusted, culturally congruent community-based organizations. It is important to recognize that the so-called short term “pop up” scenarios are not spontaneous events but the benefit from the hard and long work of community organizations over time who have built rapport with the communities they serve.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

References

Gonzalez, D., Karpman, M., & Bernstein, H. (2021). COVID-19 vaccine attitudes among adults in immigrant families in California. Retrieved November 23, 2021, from https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/103973/covid-19-vaccine-attitudes-among-adults-in-immigrant-families-in-california_0_0.pdf

Kaufman, H. W., Niles, J. K., & Nash, D. B. (2021). Disparities in SARS-CoV-2 positivity rates: Associations with race and ethnicity. Population Health Management, 2021(24), 20–26.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Age-adjusted COVID-19-associated hospitalization rates by race and ethnicity. Retrieved September 19, 2021, fromhttps://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/images/July-28_Race_Ethnicity_COVIDNet.jpg

Zephyrin, L., Radley, D. C., Getachew, Y., Baumgartner. J. C., & Schneider E. C. COVID-19 more prevalent, deadlier in U.S. counties with higher Black populations. Retrieved September 18, 2021, fromhttps://www.commonwealthfund.org/blog/2020/covid-19-more-prevalent-deadlier-us-counties-higher-black-populations

Holtgrave, D. R., Barranco, M. A., Tesoriero, J. M., Blog, D. S., & Rosenberg, E. S. (2020). Assessing racial and ethnic disparities using a COVID-19 outcomes continuum for New York State. Annals of Epidemiology, 48, 9–14.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Laboratory-confirmed COVID-19 associated hospitalizations. Retrieved September 19, 2021, fromhttps://gis.cdc.gov/grasp/COVIDNet/COVID19_3.html

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health disparities: Provisional death counts for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/health_disparities.htm

Oppel Jr., R. A., Gebeloff, R., Lai, K. K.R., Wright, W., & Smith, M. (2020). The fullest look yet at the racial inequity of coronavirus. The New York Times. Retrieved July 5, 2021, fromhttps://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/05/us/coronavirus-latinos-african-americans-cdc-data.html

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2021). Preliminary medicare COVID-19 data snapshot. Retrieved September 5, 2021, from https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-systems/preliminary-medicare-covid-19-data-snapshot

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2021). State COVID-19 data and policy actions. Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/state-covid-19-data-and-policy-actions/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Risk for COVID-19 infection, hospitalization, and death by race/ethnicity. Retrieved September 5, 2021, fromhttps://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/covid-data/investigations-discovery/hospitalization-death-by-race-ethnicity.html

Ndugga, N., Hill, L., & Artiga, S. (2021). Latest data on COVID-19 vaccinations by race/ethnicity. Retrieved November 15, 2021, from https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/issue-brief/latest-data-on-covid-19-vaccinations-race-ethnicity/

Hamel, L., Artiga, S., Safarpour, A., Stokes, M., & Brodie, M. (2021). KFF COVID-19 vaccine monitor: COVID-19 vaccine access, information, and experiences among Hispanic adults in the U.S. Retrieved November 1, 2021, from https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-covid-19/poll-finding/kff-covid-19-vaccine-monitor-access-information-experiences-hispanic-adults/

Khangura, S., Konnyu, K., Cushman, R., Grimshaw, J., & Moher, D. (2021). Evidence summaries: The evolution of a rapid review approach. Systematic Reviews, 1, 10.

Clark, E. H., Fredricks, K., Woc-Colburn, L., Bottazzi, M. E., & Weatherhead, J. (2021). Preparing for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in US immigrant communities: Strategies for allocation, distribution, and communication. American Journal of Public Health, 111, 577–581.

Manoharan, D., Lopez, C. A., Sugarman, K., Mishori, R., & Berger, Z. (2021). The US must prioritize vaccine distribution to undocumented immigrants and immigrants in detention centers. Health Affairs. Retrieved November 23, 2021, from https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/https://doi.org/10.1377/hblog20210106.483626/full/

Artiga, S., Ndugga, N., & Pham, O. (2021). Immigrant access to COVID-19 vaccines: Key issues to consider. Retrieved September 5, 2021, from https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/immigrant-access-to-covid-19-vaccines-key-issues-to-consider/

Jagannathan, M. (2021) ‘Just because we’re undocumented does not mean we’re worth less than other people’: Will undocumented immigrants get COVID-19 vaccines under Biden? Retrieved April 17, 2021, from https://www.marketwatch.com/story/just-because-were-undocumented-does-not-mean-were-worth-less-than-other-people-will-undocumented-immigrants-get-covid-19-vaccines-11611064883

Thomas, C. M., Osterholm, M. T., & Stauffer, W. M. (2021). Critical considerations for covid-19 vaccination of refugees, immigrants, and migrants. American Journal of Tropical Medicine, 104, 433–435.

Fernandez, A. (2021). We need to get more Latinx people vaccinated. Here's how. Retrieved September 5, 2021, from https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/we-need-get-more-latinx-people-vaccinated-heres-how

City of New York. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccines. Retrieved September 20, 2021, fromhttps://access.nyc.gov/programs/covid-19-vaccines/

Clark, D. (2021). Biden says undocumented immigrants should be able to get COVID vaccine without fear of ICE. Retrieved September 20, 2021, fromhttps://www.nbcnews.com/politics/politics-news/biden-says-undocumented-immigrants-should-be-able-get-covid-vaccine-n1259032

Delaware Government. (2021). COVID-19 Vaccines are Free. Retrieved November 23, 2021, from https://coronavirus.delaware.gov/vaccine/covid-19-vaccines-are-free/

Department of Homeland Security. (2021, February 1). DHS Statement on Equal Access to COVID-19 Vaccines and Vaccine Distribution Sites [Press release]. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.gov/news/2021/02/01/dhs-statement-equal-access-covid-19-vaccines-and-vaccine-distribution-sites

Massachusetts Government. (2021). COVID-19 Resources Available to Immigrants and Refugees. Retrieved September 13, 2021, fromhttps://www.mass.gov/service-details/covid-19-resources-available-to-immigrants-and-refugees

New Jersey Government. (2021). Can I get the COVID-19 vaccine if I am undocumented? Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://covid19.nj.gov/faqs/nj-information/testing-and-treatment/can-i-get-the-covid-19-vaccine-if-i-am-undocumented

Huang, P. (2021). 'You Can't Treat If You Can't Empathize': Black Doctors Tackle Vaccine Hesitancy. Retrieved September 18, 2021, fromhttps://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2021/01/19/956015308/you-cant-treat-if-you-cant-empathize-black-doctors-tackle-vaccine-hesitancy

Sullivan, J. (2021). States can reduce barriers to COVID-19 vaccines and treatment, especially for immigrants. https://www.cbpp.org/blog/states-can-reduce-barriers-to-covid-19-vaccines-and-treatment-especially-for-immigrants (accessed September 13, 2021)

Schroeder, M. (2021). Are undocumented immigrants eligible for the COVID-19 vaccine? Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.goodrx.com/covid-19/are-undocumented-immigrants-eligible-for-covid-19-vaccine

Bray, I. (2021). Are undocumented immigrants eligible for COVID-19 vaccines? Retrieved September 18, 2021, from https://www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/are-undocumented-immigrants-eligible-to-receive-a-covid-19-vaccine.html

Hui, K. (2021). Can you get the COVID-19 vaccine if you're undocumented? Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.verywellhealth.com/getting-covid-19-vaccine-undocumented-immigrant-5097402

Boundless. Can all immigrants get the COVID-19 vaccine? Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.boundless.com/blog/can-immigrants-get-the-covid-19-vaccine/

Ojeda, R. (2021). A guide to the COVID-19 vaccine if you are an immigrant in New York. Retrieved September 19, 2021, fromhttps://documentedny.com/2021/02/11/guide-to-the-covid-19-vaccine-for-immigrants-in-new-york/

Asian American Commission. COVID-19 vaccination translation project. Retrieved September 19, 2021, fromhttps://www.aacommission.org/covid-19-vaccination-translation-project/

della Cava, M., Gonzalez, D., & Plevin, R. (2020). As COVID-19 vaccine rolls out, undocumented immigrants fear deportation after seeking dose. Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2020/12/19/covid-19-vaccine-undocumented-immigrants-fear-getting-dose/3941484001/

WCAX. Vaccine outreach ramps up to reach Vt. immigrant communities. Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.wcax.com/2021/02/05/outreach-continuing-in-many-languages-to-educate-on-the-vaccine/

Correal, A. (2021). COVID-19 slammed her neighborhood. She can't find her father a vaccine. The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2021, fromhttps://www.nytimes.com/2021/02/22/nyregion/nyc-covid-vaccines.html

Bouchard, K. (2021). Outreach efforts target vaccine access and reluctance in Maine’s immigrant population. Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.pressherald.com/2021/03/28/outreach-efforts-target-vaccine-access-and-reluctance-in-maines-immigrant-population/

Tesfaye, E. (2021). African immigrant organizations are fighting to ease vaccine hesitancy. Retrieved September 19, 2021, fromhttps://www.npr.org/2021/04/05/984416410/african-immigrant-health-groups-battle-a-transatlantic-tide-of-vaccine-disinform

Benshoff, L. (2021). Vaccine clinic for Philly immigrants helps bridge gaps. Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://whyy.org/articles/vaccine-clinic-for-philly-immigrant-communities-helps-bridge-gaps-in-covid-19-care/

Jordan, M. (2021). Thousands of farmworkers are prioritized for the coronavirus vaccine. The New York Times. Retrieved September 19, 2021, fromhttps://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/01/us/coronavirus-vaccine-farmworkers-california.html?searchResultPosition=3

Noguchi, Y. (2021). The new campaign to remedy COVID-19 vaccine doubt within Black communities online. Retrieved August 31, 2021, fromhttps://www.npr.org/2021/03/19/979340051/the-new-campaign-to-remedy-covid-19-vaccine-doubt-within-black-communities-onlin

Wiley, M. (2021). Advocates work to combat vaccine distrust in ice detention facilities. Retrieved September 19, 2021, fromhttps://www.kqed.org/news/11869046/advocates-work-to-combat-vaccine-distrust-in-ice-detention-facilities

Garcia, S. (2021). Advocates working to get COVID-19 vaccine to Baltimore’s hard-hit Latino community. Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.baltimoresun.com/coronavirus/bs-hs-vaccine-latino-outreach-20210222-lju36ekrpzh5xoisp7j46nztya-story.html

Trovall, E. (2021). Undocumented Houstonians face misinformation, scams in vaccine rollout. Retrieved September 19, 2021, fromhttps://www.houstonpublicmedia.org/articles/news/politics/immigration/2021/02/12/391200/undocumented-houstonians-face-misinformation-scams-in-vaccine-rollout/

Visram, T. (2021). How will undocumented immigrants get the COVID vaccine? Retrieved September 19, 2021, from https://www.fastcompany.com/90595912/how-will-undocumented-immigrants-get-the-covid-vaccine

Whelan, A. (2021). Vulnerable immigrants in Philly are scrambling to get the COVID-19 vaccine with few resources or outreach. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://www.inquirer.com/health/coronavirus/immigrants-vaccines-covid-philadelphia-undocumented-20210302.html

Bedford, T. (2021). Fear of deportation prompts undocumented immigrants to resist COVID-19 vaccine. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://www.wgbh.org/news/local-news/2021/01/05/fear-of-deportation-prompts-undocumented-immigrants-to-resist-covid-19-vaccine

Scott, B. M. (2020, December 18). Mayor Brandon M. Scott announces initiative to mitigate disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on Latinx community [Press release]. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://mayor.baltimorecity.gov/news/press-releases/2020-12-18-mayor-brandon-m-scott-announces-initiative-mitigate-disproportionate

Rosario, I. (2021). How volunteers help Story County immigrants get COVID-19 vaccinations. Retrieved accessed September 20, 2021, from https://www.amestrib.com/story/news/2021/05/17/covid-19-vaccine-story-county-ames-coronavirus-how-volunteers-help-immigrants-vaccination/5035247001/

Campos, A. (2021). Vaccine outreach in Chicago’s Latinx communities. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://southsideweekly.com/vaccine-outreach-in-chicagos-latinx-communities/

Daniel, E. (2021). Can undocumented immigrants register for the COVID-19 vaccine? Retrieved September 19, 2021, fromhttps://www.13newsnow.com/article/news/health/coronavirus/vaccine/undocumented-immigrants-register-for-the-covid-19-vaccine/291-53f62755-a6aa-49f6-af58-165b887f0dd8

D'Avanzo, B., Lundie, K., & Lessard, G. (2021). Answers to common questions about immigrants' access to the COVID-19 vaccines. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://www.nilc.org/2021/04/12/immigrant-access-to-the-covid-19-vaccines/

Thomas, C. M., Liebman, A. K., Galván, A., Kirsch, J. D., & Stauffer, W. M. (1963). Ensuring COVID-19 vaccines for migrant and immigrant farmworkers. Am J Trop Med, 2021, 104.

Uppal, N., Erfani, P., & Sandoval, R. S. (2021). ICE must provide COVID-19 vaccines to all detained migrants. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://www.statnews.com/2021/01/12/ice-must-provide-covid-19-vaccines-to-all-detained-migrants/

Stanmyre, M. (2021). N.J. immigrant communities were hard hit by COVID. Now, they may not have ready access to vaccines, experts fear. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://www.nj.com/coronavirus/2021/01/nj-immigrant-communities-were-hard-hit-by-covid-now-they-may-not-have-access-to-vaccines-experts-fear.html

Narea, N. (2021). Few immigrants in detention have been vaccinated. That needs to change. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://www.vox.com/2021/7/14/22573814/vaccine-detention-immigration-ice-covid

Bush, D. (2021). How Florida’s COVID-19 vaccine rollout is leaving essential farmworkers behind. Retrieved September 20, 2021, fromhttps://www.pbs.org/newshour/nation/how-floridas-covid-19-vaccine-rollout-is-leaving-essential-farmworkers-behind

King, D. (2021). Ohio State partnership connects immigrants with COVID vaccine appointments. Retrieved September 19, 2021, fromhttps://www.dispatch.com/story/news/2021/05/21/ohio-state-partnership-connects-immigrants-covid-vaccine-appointments/5074962001/

Johnson, A. (2021). For immigrants, IDs prove to be a barrier to a dose of protection. Retrieved September 20, 2021, fromhttps://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2021/04/10/covid-vaccine-immigrants-id/

Blanco, A. (2021). Stamford clinic brings vaccines to immigrant communities. Retrieved September 20, 2021, from https://www.courant.com/coronavirus/hc-news-coronavirus-stamford-immigrant-vaccination-clinic-20210314-nulzkubjjvacreusis4x7aipxy-story.html

McFadden, S. M., Demeke, J., Dada, D., et al. (2021). Confidence and hesitancy during the early roll-out of COVID-19 vaccines among Black, Hispanic, and undocumented immigrant communitites: a review. Journal of Urban Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-00588-1

Kurtzman, L. (2021). UCSF partnership with San Francisco brings COVID-19 vaccinations to the Mission District. Retrieved September 13, 2021, from https://www.ucsf.edu/news/2021/02/419716/ucsf-partnership-san-francisco-brings-covid-19-vaccinations-mission-district

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the following individuals for review of an earlier presentation: Dave Barber, Marlon Bailey, Diana Ceban, Shannon Dillion, Robyn Gershon, Sang Kim, Kaveh Khoshnood, Ann Kurth, Mary Ann Marshak, Lesley Meng, Jody Merrit, Saad Omer, Carolyn Roberts, Adrian Simmons, Leonne Tannis, and Eboni Marshall Turman.

Funding

We acknowledge funding support from Science Applications International Corp (SAIC).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to drafting and/or editing the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Demeke, J., McFadden, S.M., Dada, D. et al. Strategies that Promote Equity in COVID-19 Vaccine Uptake for Undocumented Immigrants: A Review. J Community Health 47, 554–562 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01063-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-022-01063-x