Abstract

Peer-based models for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing have been implemented to increase access to testing in various settings. However, little is known about the acceptability of peer-delivered testing and counseling among people who inject drugs (IDU). During July and October 2011, data derived from the Mitsampan Community Research Project were used to construct three multivariate logistic regression models identifying factors associated with willingness to receive peer-delivered pre-test counseling, rapid HIV testing, and post-test counseling. Among a total of 348 IDU, 44, 38, and 36 % were willing to receive peer-delivered pre-test counseling, rapid HIV testing, and post-test counseling, respectively. In multivariate analyses, factors associated with willingness to access peer-delivered pre-test counseling included: male gender (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 0.48), higher than secondary education (AOR = 1.91), and binge drug use (AOR = 2.29) (all p < 0.05). Factors associated with willingness to access peer-delivered rapid HIV testing included: higher than secondary education (AOR = 2.06), binge drug use (AOR = 2.23), incarceration (AOR = 2.68), avoiding HIV testing (AOR = 0.24), and having been to the Mitsampan Harm Reduction Center (AOR = 1.63) (all p < 0.05). Lastly, binge drug use (AOR = 2.40), incarceration (AOR = 1.94), and avoiding HIV testing (AOR = 0.23) (all p < 0.05) were significantly associated with willingness to access peer-delivered post-test counseling. We found that a substantial proportion of Thai IDU were willing to receive peer-delivered HIV testing and counseling. These findings highlight the potential of peer-delivered testing to complement existing HIV testing programs that serve IDU.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Thailand continues to experience ongoing epidemics of illicit drug use and HIV infection among people who inject drugs (IDU). According to the Ministry of Public Health Thailand, the prevalence of HIV among this population remains high (between 30 and 50 %), while the prevalence of HIV in other high-risk groups, such as commercial sex workers and pregnant women, has been declining steadily over recent years [1]. To minimize the morbidity and mortality associated with HIV, many international health organizations are urging countries to scale up their voluntary HIV counseling and testing services (VCT) for IDU [2, 3], as testing can lead to the identification of undiagnosed HIV infection and early treatment [4–6]. In addition to linking IDU to proper healthcare services, knowledge of HIV serostatus may also have success in reducing HIV risk behavior among this population [7].

Although a large body of evidence supports increasing access to VCT in settings with high HIV epidemics among IDU [2, 8, 9], there exists an array of social and structural barriers that prevent IDU from accessing these services. Since the 2003 “War on Drugs” campaign launched by then Thai Prime Minster Thaksin Shinawatra, there has been continued reliance on drug law enforcement approaches to control drug trafficking and drug use in Thailand [10]. This has forced many IDU into hiding and has rendered them out of reach of potentially life-saving healthcare services [11]. Unfortunately, this policy approach has since been embraced by successive Thai governments despite lip service given to more public health-oriented approaches to dealing with illicit drug use and related harms [12–14]. Furthermore, stigmatizing attitudes of healthcare providers and the sharing of information between healthcare workers and police have been identified as factors that may cause some IDU to avoid conventional healthcare settings, including those that provide HIV testing services [11, 15]. Collectively, these social and structural barriers may contribute to a reluctance on the part of IDU to access VCT services, and consequently may increase their risk of HIV infection.

Peer-run services for IDU have been successful in extending the reach of traditional public health programs [16–18]. Task shifting, a term often used to describe the systematic delegation of tasks from physicians to workers with lower-level qualifications [19, 20], can be a strategy incorporated within peer-run services. In Africa, this decentralized approach has shown effectiveness in responding to the human health resource crisis [21, 22], especially during the current HIV/AIDS epidemic. Studies have demonstrated that with adequate training, lay workers were able to deliver healthcare services, including HIV testing [23], with comparable results to physicians [24]. In the context of IDU, expanding peer-run services to include task shifting from physicians to IDU may have potential to extend the reach of HIV services, and may minimize contact between IDU and healthcare workers who may hold stigmatizing attitudes toward the population [15].

While a large body of evidence supports task shifting as an approach to increasing access to VCT in various settings [22, 24], there are limited peer-based models of VCT for IDU in Thailand. Though peer-based models do exist in Thailand in the forms of peer-delivered education, prevention, support, and outreach activities [25, 26], peer-delivered HIV testing has yet to be explored in this context. Therefore, we sought to identify the prevalence and correlates of willingness to receive peer-delivered VCT among a community-recruited sample of IDU in Bangkok, Thailand.

Methods

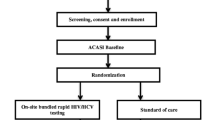

Data for these analyses were obtained from the Mitsampan Community Research Project, a collaborative research effort involving the Mitsampan Harm Reduction Center (MSHRC) (Bangkok, Thailand), the Thai AIDS Treatment Action Group (Bangkok, Thailand), Chulalongkorn University (Bangkok, Thailand), and the British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS/University of British Columbia (Vancouver, Canada). During July and October 2011, the research partners undertook a cross-sectional study involving 440 community-recruited IDU. Participants were recruited through peer-based outreach efforts and word-of-mouth and were invited to attend the MSHRC or O-Zone House (drop-in centers for IDU in Bangkok operated by non-governmental organizations) to be part of the study. Individuals residing in Bangkok or in adjacent provinces who had injected drugs in the past 6 months were eligible for participation in the study. All participants provided informed consent and completed an interviewer-administered questionnaire eliciting a range of information, including demographic data, information on drug use patterns, HIV risk behavior, health problems, interactions with police and the criminal justice system, and experiences with healthcare. Upon completion of the questionnaire, participants received a stipend of 350 Thai Baht (approximately $12 USD). The study was approved by research ethics boards at Chulalongkorn University and the University of British Columbia.

For the present analyses, we restricted the study sample to individuals who were HIV-negative or of unknown HIV serostatus. The three dependent variables of interest included: (1) willingness to receive peer-delivered pre-test counseling; (2) willingness to receive peer-delivered rapid HIV testing; and (3) willingness to receive peer-delivered post-test counseling. These variables were ascertained by asking participants in a hypothetical scenario: “Who do you want to do your HIV pre-test counseling?”, “Who do you want to conduct/administer (do) the actual rapid HIV test?”, and “Who do you want to give you the result of the rapid HIV test (including post-test counseling)?”, respectively. Participants responded from the following options: doctor, nurse, trained peer, close friend, acquaintance, anyone, and other, and were allowed to check all that apply. Peer-delivery was defined as the receiving of HIV services by a trained former or current IDU. We compared IDU who were and were not willing to receive these services through peer-delivery using bivariate statistics and multivariate logistic regression. Variables considered included: median age (≥38 years old vs. <38 years old), gender (male vs. female), higher than secondary level education (≥secondary education vs. <secondary education), frequent heroin injection (>weekly vs. ≤weekly), frequent midazolam injection (>weekly vs. ≤weekly), injected with others on a frequent basis (>75 % vs. ≤75 %), binge drug use (yes vs. no), ever incarcerated (yes vs. no), ever avoid HIV testing (yes vs. no), ever experienced barriers to accessing healthcare services (any vs. none), had unprotected sex (yes vs. no), and ever been to MSHRC (yes vs. no). All behaviors and activities referred to the previous 6 months unless otherwise indicated. The barriers to accessing healthcare services variable included the following: limited hours of operation, long wait lists/times, didn’t know where to go, jail/detention/prison, no identification card (ID), my ID is registered somewhere else, no money, don’t want healthcare provider to know I use/inject drugs, was treated poorly by healthcare professionals, fear of sharing information of drug-using status with police, difficulty keeping appointments (e.g., have to miss work), transportation, or other. To examine bivariate associations, we used the Pearson χ2 test. Fisher’s exact test was used when one or more of the cells contained values less than or equal to five. As a next step, we applied an a priori-defined statistical protocol based on examination of the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and p values to construct three separate explanatory multivariate logistic regression models. First, we constructed each model by including all variables analyzed in bivariate analyses. After noting the AIC of the model, we removed the variable with the largest p value and built a reduced model. We continued this iterative process until no variables remained for inclusion. We selected the multivariate model with the lowest AIC score. All p values were two-sided.

Results

In total, 348 IDU who were HIV-negative or of unknown HIV serostatus participated in this study; 68 (19.5 %) were female, and the median age was 38 years (IQR: 34–48 years). Among our study sample, 44, 38, and 36 % were willing to receive peer-delivered pre-test counseling, rapid HIV testing, and post-test counseling, respectively. As indicated in Table 1, in bivariate analyses, factors significantly associated with willingness to receive peer-delivered pre-test counseling included: male gender (odds ratio (OR) = 0.51; 95 % confidence interval (CI): 0.30–0.87), higher than secondary level education (OR = 2.01; 95 % CI: 1.29–3.14), midazolam injection more than once per week (OR = 1.71; 95 % CI: 1.12–2.63), injecting with others on a frequent basis (OR = 1.56; 95 % CI: 1.01–2.41), binge drug use (OR = 2.70; 95 % CI: 1.69–4.33), and having ever been to the MSHRC (OR = 1.64; 95 % CI: 1.07–2.51). Factors significantly associated with willingness to receive peer-delivered rapid HIV testing included: higher than secondary level education (OR = 1.75; 95 % CI: 1.11–2.75), binge drug use (OR = 2.24; 95 % CI: 1.40–3.58), incarceration (OR = 2.32; 95 % CI: 1.39–3.90), avoiding HIV testing (OR = 0.35; 95 % CI: 0.16–0.76), and having ever been to MSHRC (OR = 1.79; 95 % CI: 1.16–2.78). Lastly, peer-delivered post-test counseling was significantly and positively associated with binge drug use (OR = 2.24; 95 % CI: 1.40–3.59), incarceration (OR = 1.83; 95 % CI: 1.10–3.05), and negatively associated with avoiding HIV testing (OR = 0.28; 95 % CI: 0.12–0.64).

As indicated in Table 2, in multivariate analyses, factors that remained significantly associated with willingness to receive peer-delivered pre-test counseling were male gender (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 0.48; 95 % CI; 0.27–0.85), higher than secondary level education (AOR = 1.91; 95 % CI: 1.20–3.06), and binge drug use (AOR = 2.29; 95 % CI: 1.40–3.77). Higher than secondary level education (AOR = 2.06; 95 % CI: 1.27–3.39), binge drug use (AOR = 2.23; 95 % CI: 1.36–3.70), incarceration (AOR = 2.68; 95 % CI: 1.56–4.72), avoiding HIV testing (AOR = 0.24; 95 % CI: 0.10–0.52), and having ever been to the MSHRC (AOR = 1.63; 95 % CI: 1.02–2.62) remained significantly associated with willingness to receive peer-delivered rapid HIV testing. Lastly, factors that were significantly and independently associated with willingness to receive peer-delivered post-test counseling included: binge drug use (AOR = 2.40; 95 % CI: 1.48–3.93), incarceration (AOR = 1.94; 95 % CI: 1.16–3.33), and avoiding HIV testing (AOR = 0.23; 95 % CI: 0.09–0.52).

Discussion

In the present study, we found that a considerable proportion of Thai IDU were willing to receive peer-delivered VCT, with 44, 38, and 36 % of the study participants willing to receive peer-delivered pre-test counseling, rapid HIV testing, and post-test counseling, respectively. In multivariate analyses, willingness to receive peer-delivered pre-test counseling was significantly and positively associated with binge use and having higher than secondary level education, and negatively associated with male gender. Multivariate results also concluded that willingness to receive peer-delivered rapid HIV testing was positively associated with having higher than secondary level education, binge use, a history of incarceration, and having previously been to MSHRC, while negatively associated with avoiding HIV testing. Lastly, factors positively associated with willingness to receive peer-delivered post-test counseling were binge use and incarceration, whereas avoiding HIV testing was negatively associated with the dependent variable.

Our findings reveal that many IDU in our study were willing to receive VCT through peer-delivery. This supports previous studies conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa that have demonstrated the potential of employing lay healthcare workers to deliver HIV services [22, 24, 27]. Furthermore, these results complement a recent study conducted in Bangkok [28]. which indicated that approximately three-quarters of Thai IDU were willing to receive HIV testing at a drug user-run drop-in center. Although over a third of the participants were willing to access peer-delivered VCT, the rate of willingness observed here may reflect the fact that many IDU avoid HIV testing altogether and many are already being tested regularly through other sources and therefore likely do not see a need to get tested elsewhere [29, 30]. The finding that willingness to receive peer-delivered testing and post-test counseling drops by 6 % compared to pre-test counseling may be due to concerns over patient confidentiality among peers as well as the perceived ability of peers to administer HIV tests [31]. Future research using in-depth qualitative research methods are needed to understand the reasons why Thai IDU would be willing or unwilling to access peer-delivered VCT services. Nevertheless, given the various barriers that Thai IDU may face in accessing HIV services, such as HIV-related stigma and discrimination within healthcare settings [15], peer-delivered interventions that complement existing HIV programs may have potential to increase the uptake of HIV testing among this population.

The results from our study showed that binge drug use was strongly associated with all three outcomes: willingness to receive peer-delivered rapid HIV testing and pre- and post-test counseling. That IDU engaging in high intensity drug use were more willing to access these services is encouraging, given that these individuals are at higher risk of transmitting HIV through syringe sharing [32–34]. The fact that these individuals were twice as likely to receive peer-delivered HIV services than less heavy users could again be due to the stigmatization and discrimination by healthcare workers associated with being a high intensity drug user [15]. In light of these findings, efforts to implement peer-delivered VCT in settings outside of conventional healthcare settings may be important for reaching these individuals at heightened risk of HIV.

We further observed that factors associated with peer-delivered HIV testing and post-test counseling were very similar, meaning that IDU who were willing to receive peer-delivered HIV testing were also willing to receive post-test counseling through peer-delivery. This may reflect the fact that these two services complement each other, since post-test counseling refers to the process in which patients receive the results of their HIV test, discuss harm reduction strategies, and receive referrals to clinics or hospitals for further care and support [3, 35]. Our study found that having a history of incarceration was positively associated with willingness to receive both peer-delivered rapid HIV testing and post-test counseling. Given that some hospitals collect and share information concerning suspecting drug users with police [11], and that previously incarcerated IDU may fear future confrontations with police and re-incarceration, this finding may reflect the fact that these individuals may be more reluctant to access services provided in conventional public health settings. Given the large body of evidence indicating an elevated risk of HIV transmission among incarcerated IDU [36–38], it is reassuring that these individuals were more likely to access peer-delivered VCT services outside of conventional clinical environments.

Our findings also indicated that IDU who reported avoiding HIV testing were less likely to receive peer-delivered rapid HIV testing and post-test counseling. This negative association may suggest that these individuals are avoiding testing altogether, regardless of where the testing is taking place (i.e., conventional healthcare settings or peer-run drop-in centers). Various reasons for avoiding testing can include: fear of an HIV-positive test result, fear of negative reactions from family and the community, and feelings of shame and hopelessness [39–41].

Our study also found that IDU with lower than secondary level education were less likely to access peer-delivered pre-test counseling and rapid HIV testing compared to those with higher level education. These individuals may not be aware of the benefits of HIV testing and may lack knowledge of the risks associated with HIV transmission [28, 42]. In light of this finding, increased efforts for targeted outreach, educational HIV prevention interventions, and information on HIV care and treatment support are needed to reach these individuals.

Our finding that participants who have previously been to the MSHRC were more likely to get peer-delivered HIV testing suggests that drug user-run drop-in centers may serve as an additional setting for the delivery of healthcare services to Thai IDU. This supports a large body of evidence which demonstrates the value of peer-run interventions in supporting and increasing access to public health programs [16, 43, 44]. While offering services at a peer-run harm reduction center may be effective in attracting a larger number of IDU, a study by Kerr and colleagues found that female IDU were less likely to access the MSHRC [18]; yet the findings from the present study indicate that female IDU may be more willing to access peer-delivered pre-test counseling. Thus, efforts should be made to increase awareness of and access to the MSHRC, especially among these individuals.

This study has several limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional design of the study, we were unable to determine a temporal relationship between the explanatory variables and our three outcomes of interest. Second, the data collected were self-reported and may be subject to reporting biases, such as socially desirable reporting and recall biases. Third, since the study sample was not randomly selected, the study findings may not be representative of Thai IDU. Hence, this study may not be generalizable to Thai IDU and IDU in other settings.

In sum, a substantial proportion of Thai IDU were willing to receive peer-delivered VCT if it were offered at the MSHRC or similar peer-run drop-in centers. Further, our study revealed that these individuals were more likely to be engaged in high intensity drug use and have been previously incarcerated. These findings provide evidence supporting the implementation and evaluation of novel approaches to HIV testing for IDU to complement existing programs offered in conventional healthcare settings.

References

Ministry of Public Health Thailand. (2011). Thailand health profile, 2008–2010. Bangkok: Ministry of Public Health Thailand.

WHO, UNODC, & UNAIDS. (2009). WHO, UNODC, UNAIDS technical guide for countries to set targets for universal access to HIV prevention, treatment and care for injecting drug users. Geneva: WHO.

WHO, & UNODC. (2009). Guidance on testing and counselling for HIV in settings attended by people who inject drugs: Improving access to treatment, care and prevention. Geneva: WHO.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. (2010). HIV testing: Increasing uptake and effectiveness in the European Union. Stockholm: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control.

Girardi, E., Sabin, C., & Monforte, A. (2007). Late diagnosis of HIV infection: Epidemiological features, consequences and strategies to encourage earlier testing. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 46, S3–S8.

Wood, E., Kerr, T., Hogg, R., et al. (2006). Impact of HIV testing on uptake of HIV therapy among antiretroviral naive HIV-infected injection drug users. Drug and Alcohol Review, 25, 451–454.

Schlumberger, M., Desenclos, J., Papaevangelou, G., Richardson, S., & Ancelle-Park, R. (1999). Knowledge of HIV serostatus and preventive behaviour among European injecting drug users: Second study. European Journal of Epidemiology, 15, 207–215.

Denison, J., O’Reilly, K., Schmid, G., Kennedy, C., & Sweat, M. (2008). HIV voluntary counseling and testing and behavioral risk reduction in developing countries: A Meta-analysis, 1990–2005. AIDS and Behavior, 12, 363–373.

Fonner, V., Denison, J., Kennedy, C. E., O’Reilly, K., & Sweat, M. (2012). Voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) for changing HIV-related risk behavior in developing countries. Coachrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001224.pub4.

Human Rights Watch. (2004). Not enough graves: The war on drugs, HIV/AIDS, and violations of human rights. Thailand. Retrieved from http://www.hrw.org/en/node/12005/section/2.

Human Rights Watch, & Thai AIDS Treatment Action Group. (2007). Deadly denial: Barriers to HIV/AIDS treatment for people who use drugs in Thailand (No. 17). Thailand.

Human Rights Watch. (2012). Thailand: Downward slide on human rights. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from http://www.hrw.org/news/2012/01/23/thailand-downward-slide-human-rights.

Office of the Narcotics Control Board. (2011). National narcotics control policy on kingdom’s unity for victoriy over drugs strategy. Bangkok: Office of the Narcotics Control Board. Retrieved from http://en.oncb.go.th/file/information_policy.html.

Smith, P. (2008). Southeast Asia: Thai government in new drug crackdown. StoptheDrugWar.org. Retrieved from http://stopthedrugwar.org/chronicle/2008/nov/14/southeast_asia_thai_government_n.

Chan, K., Stoove, M., Sringernyuang, L., & Reidpath, D. (2008). Stigmatization of AIDS patients: Disentangling Thai nursing students’ attitudes towards HIV/AIDS, drug use, and commercial sex. AIDS and Behavior, 12, 146–157.

Broadhead, R., Heckathorn, D., Anthony, D., et al. (1998). Harnessing peer networks as an instrument for AIDS prevention: Results from a peer-driven intervention. Public Health Reports, 113, 42–57.

Hayashi, K., Wood, E., Wiebe, L., Qi, J., & Kerr, T. (2010). An external evaluation of a peer-run outreach-based syringe exchange in Vancouver, Canada. International Journal of Drug Policy, 21(5), 418–421.

Kerr, T., Hayashi, K., Fairbairn, N., et al. (2010). Expanding the reach of harm reduction in Thailand: Experiences with a drug user-run drop-in centre. International Journal of Drug Policy, 21, 255–258.

Bemelmans, M., Van Den Akker, T., Ford, N., et al. (2010). Providing universal access to antiretroviral therapy in Thyolo, Malawi through task shifting and decentralization of HIV/AIDS care. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 15(12), 1413–1420.

Fulton, B., Scheffler, R., Sparkes, S., et al. (2011). Health workforce skill mix and task shifting in low income countries: A review of recent evidence. Human Resources for Health, 9(1), 1.

Price, J., & Binagwaho, A. (2010). From medical rationing to rationalizing the use of human resources for AIDS care and treatment in Africa: A case for task shifting. Developing World Bioethics, 10(2), 99–103.

Sanjana, P., Torpey, K., Schwarzwalder, A., et al. (2009). Task-shifting HIV counselling and testing services in Zambia: The role of lay counsellors. Human Resources for Health, 7, 44.

McCollum, E., Preidis, G., Kabue, M., et al. (2010). Task shifting routine inpatient pediatric HIV testing improves program outcomes in urban Malawi: A retrospective observational study. PLoS ONE, 5(3), e9626.

Callaghan, M., Ford, N., & Schneider, H. (2010). A systematic review of task-shifting for HIV treatment and care in Africa. Human Resources for Health, 8, 8.

Khumalo-Sakutukwa, G., Morin, S. F., Fritz, K., et al. (2008). Project accept (HPTN 043): A community-based intervention to reduce HIV incidence in populations at risk for HIV in sub-saharan Africa and Thailand. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 49(4), 422–431.

The Global Fund To Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. (2012). Grant portfolio: Thailand. Retrieved from http://portfolio.theglobalfund.org/en/Grant/List/THA.

Selke, H., Kimaiyo, S., Sidle, J., et al. (2010). Task-shifting of antiretroviral delivery from health care workers to persons living with HIV/AIDS: Clinical outcomes of a community-based program in Kenya. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 55(4), 483–490.

Ti, L., Hayashi, K., Kaplan, K., et al. (2012). HIV testing and willingness to get HIV testing at a peer-run drop-in centre for people who inject drugs in Bangkok, Thailand. BMC Public Health, 12, 189.

Kellerman, S. E., Lehman, J. S., Lansky, A., et al. (2002). HIV testing within at-risk populations in the United States and the reasons for seeking or avoiding HIV testing. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 31(2), 202–210.

Martin, M., Vanichseni, S., Suntharasamai, P., et al. (2011). Enrollment characteristics and risk behaviors of injection drug users participating in the Bangkok Tenofovir Study, Thailand. PLoS ONE, 6(9), e25127.

Baiden, F., Akanlu, G., Hodgson, A., et al. (2007). Using lay counsellors to promote community-based voluntary counselling and HIV testing in rural northern Ghana: A baseline survey on community acceptance and stigma. Journal of Biosocial Science, 39, 721–733.

Chakrapani, V., Newman, P., Shunmugam, M., & Dubrow, R. (2011). Social-structural contexts of needle and syringe sharing behaviours of HIV-positive injecting drug users in Manipur, India: A mixed methods investigation. Harm Reduction Journal, 8, 9.

Kerr, T., Small, W., Buchner, C., et al. (2010). Syringe sharing and HIV incidence among injection drug users and increased access to sterile syringes. American Journal of Public Health, 100(8), 1449–1453.

Rhodes, T., Judd, A., Mikhailova, L., et al. (2004). Injecting equipment sharing among injecting drug users in Togliatti City, Russian Federation: Maximizing the protective effects of syringe distribution. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 35, 293–300.

WHO, & UNAIDS. (2007). Guidance of provider-initiated HIV testing and counselling in health facilities. Geneva: WHO.

Dolan, K., Kite, B., Black, E., Aceijas, C., & Stimson, G. (2007). HIV in prison in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Infectious Diseases, 7(1), 32–41.

Kheirandish, P., Seyedalinaghi, S., Hosseini, M., et al. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of HIV infection among male injection drug users in detention in Tehran, Iran. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 53(2), 273–275.

Suntharasamai, P., Martin, M., Vanichseni, S., et al. (2009). Factors associated with incarceration and incident human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection among injection drug users participating in an HIV vaccine trial in Bangkok, Thailand, 1999–2003. Addiction, 104(2), 235–242.

Awad, G., Sagrestano, L., Kittleson, M., & Sarvela, P. (2004). Development as a measure of barriers to HIV testing among individuals at high risk. AIDS Education and Prevention, 16(2), 115–125.

Ford, K., Wirawan, D., Sumantera, G., Sawitri, A., & Stahre, M. (2004). Voluntary HIV testing, disclosure, and stigma among injection drug users in Bali, Indonesia. AIDS Education and Prevention, 16(6), 487–498.

Ma, W., Detels, R., Feng, Y., et al. (2007). Acceptance of and barriers to voluntary HIV counselling and testing among adults in Guizhou province, China. AIDS, 21(Suppl 8), S129–S135.

Moyer, L., Brouwer, K., Ramos, R., et al. (2008). Barriers and missed opportunities to HIV testing among injection drug users in two Mexico—US border cities. Drug and Alcohol Review, 27(1), 39–45.

Boyd, S., Johnson, J., & Moffat, B. (2008). Opportunities to learn and barriers to change: Crack cocaine use in the Downtown Eastside of Vancouver. Harm Reduction Journal, 5, 34.

Weeks, M., Li, J., Dickson-Gomez, J., et al. (2009). Outcomes of a peer HIV prevention program with injection drug and crack users: The risk avoidance partnership. Substance Use and Misuse, 44(2), 253–281.

Acknowledgments

We would particularly like to thank the staff and volunteers at the Mitsampan Harm Reduction Center, Thai AIDS Treatment Action Group and O-Zone House for their support and Dr. Niyada Kiatying-Angsulee of the Social Research Institute, Chulalongkorn University, for her assistance with developing this project. We also thank Tricia Collingham, Deborah Graham, Caitlin Johnston, Calvin Lai and Peter Vann for their research and administrative assistance, and Prempreeda Pramoj Na Ayutthaya, Arphatsaporn Chaimongkon and Sattara Hattirat for their assistance with data collection. The study was supported by Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research. KH is supported by a University of British Columbia Doctoral Fellowship. This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program through a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Inner City Medicine which supports EW.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Ti, L., Hayashi, K., Kaplan, K. et al. Willingness to Access Peer-Delivered HIV Testing and Counseling Among People Who Inject Drugs in Bangkok, Thailand. J Community Health 38, 427–433 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-012-9635-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-012-9635-z