Abstract

It is generally assumed that gamblers, and particularly people with gambling problems (PG), are affected by negative perception and stigmatisation. However, a systematic review of empirical studies investigating the perception of gamblers has not yet been carried out. This article therefore summarises empirical evidence on the perception of gamblers and provides directions for future research. A systematic literature review based on the relevant guidelines was carried out searching three databases. The databases Scopus, PubMed and BASE were used to cover social scientific knowledge, medical-psychological knowledge and grey literature. A total of 48 studies from 37 literature references was found. The perspective in these studies varies: Several studies focus on the perception of gamblers by the general population, by subpopulations (e. g. students or social workers), or by gamblers on themselves. The perspective on recreational gamblers is hardly an issue. A strong focus on persons with gambling problems is symptomatic of the gambling discourse. The analysis of the studies shows that gambling problems are thought to be rather concealable, whereas the negative effects on the concerned persons‘ lives are rated to be quite substantial. PG are described as “irresponsible” and “greedy” while they perceive themselves as “stupid” or “weak”. Only few examples of open discrimination are mentioned. Several studies however put emphasis on the stereotypical way in which PG are portrayed in the media, thus contributing to stigmatisation. Knowledge gaps include insights from longitudinal studies, the influence of respondents‘ age, culture and sex on their views, the relevance of the type of gambling a person is addicted to, and others. Further studies in these fields are needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Gambling is increasingly perceived as normal leisure activity in most Western societies. A large part of the adult population participates in some sort of gambling such as lotteries or sports betting. Unlike many other leisure activities, gambling may however cause adverse impacts on the health and wellbeing of an individual and his/her environment. The concept of “gambling harm” summarises a wide spectrum of negative consequences such as financial problems, disruptions to work/study, damage to the health, emotional and/or psychological distress, deterioration in relationships, cultural harms and criminal activities (Browne et al. 2016). Due to its potential negative effects on health and well-being, harmful gambling can be placed in the same category as smoking, problematic alcohol and recreational drug use (Browne et al. 2020).Footnote 1

One negative consequence of gambling is stigmatisation. Stigmatising behaviour has several functions; among others it stresses the difference between “normal” and stigmatised behaviour in an attempt to enforce norm-complying behaviour. Persons with gambling problems are often perceived in a negative light and exposed to stigmatisation (Carroll et al.; Hing et al. 2016b; Palmer et al. 2017). However, stigmatisation of people with gambling problems has so far received little attention in research (Hing et al. 2013). The few studies that have looked into it have clear findings (Dhillon et al. 2011; Hing and Russell 2017a; Miller and Thomas 2017a; Palmer et al. 2017; Peter et al. 2018). A number of persons with gambling problems internalises the negative views of the society, perceiving their problems as personal failure. This causes self-stigmatisation, extending into a downward spiral. Moreover, stigmatisation is a major therapeutic obstacle because affected persons are hesitant to reveal themselves and might generally withdraw from relationships (Brown and Russell 2019; Hing et al. 2013; Miller and Thomas 2017b).

It is assumed that not only problem gambling, but every form of (risky) gambling is to some extent stigmatised (Horch and Hodgins 2015). However, research so far has mostly focused on the stigmatisation of persons with gambling problems (Miller and Thomas 2017b).

In view of the situation just described, we aim to systematise empirical evidence on the perception of gamblers. To our knowledge, a systematic literature review on empirical studies investigating the perceptions of people who gamble or have gambling problems does not yet exist, although intensified research activities are needed in order to successfully counteract (self-)stigmatisation (Schomerus and Rumpf 2017).

Method

Initial Search and Study Selection

The research strategy was based on guidelines for conducting systematic literature reviews (Card and Little 2016; Cooper et al. 2009; Liberati et al. 2009; Rosenthal 2010). Data was collected from December 13 to 18, 2018 in three scientific databases. The databases Scopus, PubMed and BASE were selected to ensure a broad range of results, taking medical-psychological knowledge, social scientific knowledge and grey literatureFootnote 2 into account.

To determine the search terms, we collected 69 potentially relevant terms for the electronic search. After discussion of the individual keywords, the search strings were systematically reduced by the authors' evaluations of relevance for each term. The truncated “gambl*” (for: gambling) was then linked to one of the following search terms by an AND-condition: “Stigma*”, “public attitude”, “social attitude”, “devaluation", “discrimination”, “labelling”, “prejudice”, “rejection”, “responsibility “, “self-control”, “self-esteem”, “self-worth”, “shame”, “social distance” and “stereotyp*”. A separate search was performed for each of the search term pairs in each database. The literature search was only limited (inclusion criteria) in terms of language (English) and publication date (from 1980 onwards). This year was chosen as a starting point because pathological gambling was first included in the DSM-III in 1980. Any form of scientific knowledge (journal articles, grey literature, talks, etc.) was allowed.

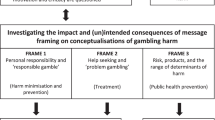

A total of 5.014 literature references was found. All individual database searches were exported and subsequently integrated, so that duplicates could be easily removed. As a next step, all literature references were screened on the base of title and abstract. Subsequently, 4.874 literature references could be removed, as they were not relevant to the review. Controversial cases were discussed and a joint decision was made. A large number of references could thus be removed as they were obviously off topic. 143 references were then classified as potentially relevant. By taking a closer look at the analysis and results section, more studies were removed. The remaining references were screened for eligibility by the two authors by reading the full text (n = 40). 37 of these citations have proved relevant and are included in the qualitative synthesis. The reasons for the exclusion are portrayed in Fig. 1.

Systematisation of Literature and Contents

To systematise the relevant literature, the study characteristics were analysed in a descriptive way with focus on methodological and structural aspects such as the perspective (e. g. therapists on persons with gambling problems), type of sample (e. g. students, public), method of analysis (e. g. descriptive, content analysis) and country of origin of the sample.

Second, the content-related aspects were categorised. As a basis, the shared dimensional features of stigma proposed by Jones (1984) were used. Jones developed six categories to systematically describe stigma and to document the differences between stigmas. The category “concealability” describes the degree to which a stigma is visible to others. “Course” refers to the persistance of a stigma over time, “disruptiveness” to the degree to which a stigma interferes with social interactions. The category “aesthetics” refers to the potential to provoke a rejective attitude. “Origin” describes whether a stigma is believed to be inborn, accidental, or deliberate. Lastly, the category “peril” relates to the degree to which a stigma is understood as a personal menace or threat. The relevant literature was thoroughly searched to identify all aspects fitting into these categories. For practicability reasons, concealability and aesthetics were combined under the term of “concealability” because both dimensions basically refer to the visibilty of a condition.

Beyond Jones’ shared dimensional features of stigma, Hing et al. (2013) have developed further categories to describe the process of stigma formation. The category “labelling” describes the process of finding and assigning names or labels for certain human characteristics. The persons or groups to whom such labels are attached are identified with negative attributes and stereotypes (“stereotyping”). Consequently, the majority society distances itself from these persons or groups (“separation”). The differentiation between “the normal” and “the other” triggers a negative “emotional response”. When negative attitudes manifest in behaviour, the stigmatised persons experience a specific form of social exclusion (“status loss and discrimination”). As these categories build the reference for most current works either directly or indirectly (e. g. Brown and Russell 2019), they were also included in the present analysis.

Results

Study Characteristics

A total of 37 literature references (e. g. journal articles) was found. Some of these references contained several studies. E. g., an article may describe surveys obtained from different samples (e. g. from the general public, social workers and gamblers). Two publications each worked with the same sample but inquired on different topics (Hing and Russell 2017a and Hing and Russell 2017b) or used different survey methods (Hing et al. 2015 and Hing et al. 2016d); consequently, they were also listed as separate studies. Altogether, 48 surveys were obtained. The chosen method has the advantage of portraying each individual study separately, implicitly accepting that certain samples attain more weight.

Only one study (Crawford et al. 1989) was published before the beginning of the new millennium. Most of the studies were published after 2010. Apparently, the issue has not played a significant role in scientific debate before.

In terms of analytic methods and samples, the studies were very heterogeneous. Tables 1, 2 and 3 portray relevant methodological and structural characteristics of all studies. 17 studies used a qualitative, 26 a quantitative methodology. Five studies used both methodological approaches. Of the 17 qualitative studies, nine used conventional personal in-depth interviews, three used focus groups, two discourse analyses and three film analyses. 20 out of 26 quantitative studies conducted an online survey. The remaining six studies consisted of vignette studies (n = 5) and one corpus-based text analysis. Almost exclusively, cross-sectional surveys were carried out. Only one film analysis (Chan and Ohtsuka 2011) could be categorised as longitudinal study. The large variety of methods challenged the synthesis of the results obtained in these studies.

With respect to their origin, 40 from the total of 48 studies were journal articles, which, owing to the peer review process, usually guarantee a higher quality of results; although even there the quality of many of the studies could be considered as low as e. g. descriptions as to the methods used were missing. Seven (Carroll et al. 2013; Hing et al. 2015) studies stemmed from grey literature; one was a presentation (Feeney 2013). One of the grey literature sources, namely the research report by Hing et al. (2015), encompasses three very detailled studies described on a total of 282 pages and will take up ample room in the following chapters.

The vast majority of studies were carried out with either Australian (n = 19) or Canadian samples (n = 10), which might impact the generalisability of the results of the present study. Four studies were carried out with Finnish and four with US samples. One study each was conducted in France, Spain, Sweden, the United Kingdom and Israel. Two studies were based on international mixed samples. Two out of the three film analyses took an international perspective, whereas Chan and Ohtsuka (2011) considered only Hong Kong films. In addition, there was a corpus-based text analysis of newspaper articles from Singapore (Leung 2016).

Representative samples were clearly outnumbered by convenience samples, which also affects the overall quality of the results. Population representative studies were available for Australia, Canada, Finland, Sweden and the UK. Taken together, more females were interviewed in the studies than men, which is why the following tables identify the proportion of females in the samples.

Perception of Gamblers

Stigmatisation of gambling and gamblers is a comparatively new topic for research. In order to get an impression of the dimension of the issue, several studies compared the degree of stigmatisation for gamblers with the degree of stigmatisation for persons with various substance and non-substance use disorders, mental health problems and/or other conditions. In addition, this information might be useful during the development of health policy measures. For example, comparable stigma reduction strategies from other areas (e. g. mental illness) could be adopted for the gambling field.

In general, drug use was more heavily stigmatised than alcohol abuse (Arbour-Nicitopoulos et al. 2010; Feeney 2013), alcohol abuse more than problem gambling (Arbour-Nicitopoulos et al. 2010; Feeney 2013; Hing et al. 2015; Horch and Hodgins 2008). Mental health problems were less stigmatised than problem gambling (Arbour-Nicitopoulos et al. 2010; Feeney 2013); however, persons with schizophrenic disease were more heavily stigmatised than persons with gambling problems (Hing et al. 2015; Horch and Hodgins 2008).

Stigmatisation levels were higher for persons who were officially diagnosed as disordered gamblers (Palmer et al. 2018). Self-stigmatisation in persons with gambling problems increased with age, female sex, lower self-esteem, higher problem gambling severity scores, and use of secrecy as a coping mechanism (Hing and Russell 2017b).

Not all forms of gambling were equally stigmatised. Sports bettors were less heavily stigmatised than other gamblers (Lopez-Gonzalez et al. 2018). EGM gamblers were seen and desribed in a particularly negative way (Miller and Thomas 2017b). This could be related to the fact that in some games of chance, the gamblers’ skills play or at at least attributed a greater role. Apparently, gambling as an activity was not per se stigmatised, only problem gambling (Hing et al. 2015).

Dimensions of Stigma

The following sections sum up the contents with reference to the dimensions of stigma as proposed by Jones (1984), as well as to the categories for the process of stigma formation as described in Hing et al. (2013).

Concealability

Most of the studies‘ respondents thought that it was easier to conceal problem gambling than alcohol use disorder or schizophrenia (Hing et al. 2015, 2016d). However, the majority also judged problem gambling to be as “at least somewhat noticeable” (Hing et al. 2015, 2016d) or “fairly noticeable” (Hing et al. 2016e). The fact that their condition seemed rather obvious to the public was not reflected by persons with gambling problems (Hing et al. 2015). This could lead to gambling disorder receiving less attention compared to other issues in society, such as drug and alcohol addiction.

Disruptiveness

When interviewed on the disruptiveness of problem gambling, most people indicated that problem gambling had at least a large effect on the affected persons‘ ability to work or study, to live independently and to be in a serious relationship (Hing et al. 2015, 2016d). Problem gambling was perceived to be “quite disruptive” (Hing et al. 2016e), “disruptive” (Hing et al. 2015) or “highly disruptive” (Hing et al. 2016d), even more than alcohol use disorder but less than schizophrenia (Hing et al. 2015). Persons with gambling problems seemed to anticipate that the public considered them to lead disruptive lifes, which in turn increased self-stigma (Hing and Russell 2017a).

Recoverability

Problem gambling was perceived to be recoverable by most respondents (Hing et al. 2015, 2016d, e), more so than schizophrenia (Hing et al. 2016d) and more (Blomqvist 2009) or similarly than alcohol use disorder (Hing et al. 2015). Change optimism was higher for persons with tobacco abuse but lower for persons using medical or illegal drugs (Blomqvist 2009). Untreated, recovery from problem gambling was thought to be easier than from mind altering substance addictions (Koski-Jännes et al. 2012); in the same vein, treatment was rated to be more important for “hard drugs” or alcohol than for gambling (Blomqvist 2009).

In Blomqvist (2009), the recoverability from problem gambling was rated high, whether with or without treatment. In Cunningham et al. (2011) and Feeney (2013), respondents were divided on whether it was possible for persons with gambling problems to recover without outside assistance. Professionals rated self-change as more difficult than lay persons (Koski-Jännes et al. 2012). Interestingly, there seem to be cultural differences: French professionals believed more in untreated recovery than their Finnish counterparts (Koski-Jännes and Simmat-Durand 2017). Compared to the general public, persons with gambling problems also rated treatment as less necessary (Cunningham et al. 2011).

Peril to Others and Self

Individuals with gambling problems are generally not perceived as being dangerous (Dhillon et al. 2011; Hing et al. 2016d; Peter et al. 2018). In Hing et al. (2015) problem gambling was thought to be “somewhat perilous”; but the respondents thought it unlikely that persons with gambling problems would cause peril to others and likeley that they would harm themselves.

Both in terms of peril to others and peril to self, persons with gambling problems were thought to be less dangerous than persons with alcohol use disorder or schizophrenia (Hing et al. 2015; Horch and Hodgins 2015). Interestingly, different types of games seem to be rated differently: Internet gamers were seen as less dangerous to be around than eSports gamblers or traditional casino gamblers (Peter et al. 2018).

Origin

The causes for gambling disorder were seen as rooted in personality traits, such as having an addictive personality (Carroll et al. 2013; Feeney 2013) or not enough willpower; lack of willpower might also imply that gambling habits of friends and relatives are taken over (Feeney 2013). Another issue mentioned was lack of control, discipline or even intelligence (Miller et al. 2014). In Horch and Hodgins (2008), bad character traits and stressful live events were seen as responsible for gambling disorder. Stressful life circumstances were identified as the most likely cause (Dhillon et al. 2011; Hing et al. 2015, 2016d, e). Finnish and French social workers seemed to think that the causes could be found in society rather than in the individual. Whereas the Finnish social workers regarded the individual as responsible for recovery, their French counterparts disagreed (Egerer 2013). In most studies however, the individual was thought to be responsible (Blomqvist 2009; Gay et al. 2016; Horch and Hodgins 2008, 2015; Konkolÿ Thege et al. 2015; Koski-Jännes and Simmat-Durand 2017; Koski-Jännes et al. 2012; Miller and Thomas 2017b).

In general, character flaws were viewed as being more associated with behavioral addictions than with substance use disorders (Konkolÿ Thege et al. 2015). Accordingly, the general public, professionals and the clients themselves thought that persons with gambling problems were responsible for their problem, more so than persons with substance use disorders (Koski-Jännes and Simmat-Durand 2017; Koski-Jännes et al. 2012).

Emotional Reactions: Pity, Anger and Fear

Following Angermeyer and Matschinger (2003), three emotional reactions—pity, anger and fear—were measured in a number of studies. Mostly, the respondents indicated that they would feel pity towards persons with gambling problems, with some anger and some fear (Hing et al. 2015, 2016e). In Gay et al. (2016) and Horch and Hodgins (2008), respondents felt anger and pity towards problem gamblers equally or almost equally strong, but lower levels of fear. Both eSports gamblers and casino gamblers attracted more fear than the Internet gamer (Peter et al. 2018).

Respondents were more likely to pity persons suffering from schizophrenia than persons with gambling problems or with alcohol use disorder; the latter being at more or less the same level. In terms of anger, respondents felt as much anger against persons with gambling problems as against persons with alcohol disorder; again, persons with schizophrenia met with less anger. Respondents were more likely to fear persons with alcohol disorder and schizophrenia than persons with gambling problems (Hing et al. 2015).

Dimensions of Stigma Creation

Dimensions of stigma creation include labelling, stereotyping, status loss and discrimination and social distancing (Hing et al. 2013).

Labelling

Although labels are necessary—e. g. for obtaining adequate treatment (Grunfeld et al. 2004)—they contribute substantially to the creation of stigma (Hing et al. 2016b; Peter et al. 2018). Several studies investigate on whether problem gambling was perceived as mental health disorder, physical health disorder, addiction, disease/illness, or as a diagnosable condition.

Gambling problems were either attributed to addiction (Hing et al. 2015) or equally to addiction and disease (Cunningham et al. 2011). Additionally, the majority of the respondents believed that problem gambling was a diagnosable condition (Hing et al. 2015). In an early study by Crawford et al. (1989), “compulsive gambling” was rated to be a disease rather than a “habit” or a “sin”.

Generally, the risk of becoming addicted to gambling was rated to be lower than to substances such as alcohol or drugs (Konkolÿ Thege et al. 2015; Lang and Rosenberg 2017); however, in Blomqvist (2009), it was rated to be slightly higher than to alcohol.

Stereotyping

Stereotypes of persons with gambling problems probably stem from culturally transmitted beliefs rather than from direct interactions and are therefore difficult to confront (Hing et al. 2016e). Frequent attributions included “irresponsible” (Hing et al. 2015, 2016e; Horch and Hodgins 2008, 2015; Miller and Thomas 2017b), “greedy” (Hing et al. 2015, 2016e; Horch and Hodgins 2013; Miller and Thomas 2017b), “antisocial” (Hing et al. 2015, 2016e; Horch and Hodgins 2013), “foolish” (Hing et al. 2015, 2016b, e), “impulsive” and “irrational” (Hing et al. 2015, 2016e; Horch and Hodgins 2013) and “untrustworthy” (Hing et al. 2015, 2016e; Horch and Hodgins 2015) on the part of the public.

Persons with gambling problems described themselves as “stupid” (Hing et al. 2015, 2016b; Miller and Thomas 2017b), “weak” or “losers” (Hing et al. 2015, 2016b). The gamblers also assumed that the general population judged them as “impulsive, irresponsible, irrational, anti-social, greedy, untrustworthy, unproductive, and deviant” (Hing et al. 2015), which is likely to increase self-stigma (Hing and Russell 2017a).

People with gambling problems also sensed that the media contributed to the formation of stereotypes by their emphasis on the negative consequences of gambling (Miller and Thomas 2017b, 2018) and on the responsibility of the individual (Miller et al. 2014). Persons with gambling problems were frequently portrayed as a deviant group, as opposed to the rest of the society, and they were perceived as having only themselves to blame (Leung 2016; Miller et al. 2016).

Studies focusing on the portrayal of gamblers in the movies described images of masculinity and coolness, self-control and the ability to enjoy oneself (Egerer and Rantala 2015). Only gamblers with limited abilities developed problems (Sulkunen 2007). However, the portrayal of gamblers has changed over the decades: from a sinner in the 50s over skilful and intelligent persons in the 80s to funny characters with a lack of moral in the 2000s (Chan and Ohtsuka 2011).

Status Loss and Discrimination

Alcohol disorder and schizophrenia were rated to be more likely to result in status loss than problem gambling (Hing et al. 2015). There was moderate agreement that a person would lose status or experience discrimination because of problem gambling, mostly in the fields of employment, child care and relationships (Hing et al. 2016e). Horch and Hodgins (2015) determined a discrimination value halfway between “seldom” and “sometimes”, suggesting that discrimination of individuals with gambling problems happens infrequently. Consequently, examples of discrimination were found to be rare (Hing and Russell 2017a), which was attributed to the concealability of problem gambling (Horch and Hodgins 2015) and the fact that many affected persons do not disclose their gambling problem. Negative responses included comments about wasting money or suggestions to do something better with life (Hing et al. 2016b).

Social Distance

Several studies investigated on the willingness of particpants to engage with persons with gambling problems. Compared to persons with alcohol disorder or schizophrenia, the respondents were less likely to distance themselves (Hing et al. 2015).

Most participants wished to keep distance or at least “some distance” to persons in this condition (Hing et al. 2015, 2016e; Lang and Rosenberg 2017; Rockloff and Schofield 2004), especially to persons whose condition had been officially diagnosed (Palmer et al. 2018). In other studies, the desire for segregation was found to be low (Gay et al. 2016; Horch and Hodgins 2008). Persons who were more familiar with persons experiencing gambling problems wanted less social distance (Dhillon et al. 2011). Creating more familiarity with the issue could help to develop effective strategies in the effort to confront stigma.

The desire for social distance was also influenced by the type of gambling. Participants were less willing to engage with casino gamblers than with e-sport gamblers, and more willing to engage with Internet gamblers than with e-sport gamblers (Peter et al. 2018).

Discussion

The systematic review on studies dealing with the perception of gamblers revealed that research on this topic commenced to gather pace mainly after 2010, and was carried out primarily in Australia and Canada. Population representative studies were found for Australia, Canada, Finland, Sweden and the UK. Almost exclusively, cross-sectional surveys were carried out. In consequence, a change in public perception of gamblers could not be investigated. Neither were studies available that focussed primarily on effects of the respondents‘ sex and age, although this aspect was considered as one issue among others in some studies (e. g. Hing and Russell 2017b). As the vast majority of studies concentrated on problem gambling, conclusions on the perception of recreational gamblers could not be drawn. It would be of interest to have more and more comparable data from different countries and/or over time.

The analysis of the studies‘ contents showed that problem gambling was thought to be rather concealable. However, the negative effects on the concerned persons‘ lives were judged to be quite substantial. With respect to treatment and recovery, the opinions were divided. Most respondents seemed to think that the individual is responsible for finding a way out of the problem. The concept of problem gambling as an addiction does not seem to have found its way into the minds of the public. The provision of adequate information could be helpful.

Persons with gambling problems were described with a series of negative attributes. While some of these attributions have some basis in truth, others go well beyond the mark. This negative perspective was mirrored in the gamblers’ negative picture of themselves, as a sign of self-stigmatisation. The way in which persons with gambling problems are portrayed in the media helps to aggravate this process. This could be another starting point for countering stigmatisation.

Only few examples of open discrimination of persons with gambling problems were mentioned, probably because the condition can be concealed more easily than other addictions. The general public wanted to keep at least some distance to persons with gambling problems; the desire for distance however diminished with increased familiarity. This knowledge can be used, for example, for public awareness campaigns that show that “ordinary people” can develop gambling problems. As one study (Peter et al. 2018) showed, the desire for social distance may vary for different types of gambling. It would therefore in future studies be informative to compare the perspectives on gamblers of slot machines, casino gamblers, sports bettors and other gamblers. Greater familiarity with problem gambling and gamblers could effectively counteract stigmatisation.

There are several shortcomings in the present work, often caused by limited human and financial resources. For example, the use of different search terms, searches in other databases, and generally searches in other sources (e. g. manual searches) would have rendered further results. Due to time restrictions, the quality of the studies was not rated. The consideration of publications in other languages would also have been reasonable. Besides, the lack of formal assessment of intra- and inter-rater reliability can be criticised. Selection of the studies was made as team effort and all relevant decisions were extensively discussed. It would also be worth considering combining parts of the studies using meta-analytical statistical methods in the future.

Although a good number of studies focus on the public perception of persons with gambling problems, other aspects have been examined less well. Research on this topic started rather recently. In many countries, therefore, there is a lack of population-representative surveys on the perspective of gamblers. Moreover, it is noticeable that longitudinal studies are not available. These are however necessary to obtain insight into the dynamics of the phenomenon. It would also be interesting to monitor individual persons with gambling problems over a longer period of time with a qualitative research approach. Such a research project could provide important insights into the process of stigmatisation and in particular self-stigmatisation.

An interesting line of research is to look into the portrayal of persons with gambling problems on part of the media (press, official documents, films etc.). Since several studies have already been carried out, complementary research activities could start from a solid basis. The ways in which persons with gambling problems are portrayed in the media of different countries would also make an interesting topic of investigation, especially in countries where this issue has not yet been addressed.

Aspects such as the influence of the respondents ‘ sex and age on their attitudes have only been touched on briefly, if at all. Also, the influence of cultural aspects has hardly been taken into focus (Dhillon et al. 2011). In the same vein, there are only few studies empirically examining the public’s views and opinions on recreational gambling. Moreover, only few studies on the perspective of professionals on their clients exist, which is a clear indication that such research in this field should be intensified in the future, as the results are needed to advance stigma-free treatment (Schomerus 2017). This, in turn, would be necessary to ease access to treatment for those affected. To achieve this goal, targeted health policy measures should be enforced that systematically address stigmatisation. Individual harm might be diminished as a result, thereby improving public health.

Change history

21 May 2021

The following OA funding note is address above reference section: Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Notes

The term “person with gambling problem” will in the following be used for persons who experience problems with gambling, regardless of whether a diagnosis has been made or not.

The term “grey literature” refers to scientific works that are difficult to access via conventional access paths such as citation databases (e. g. Web of Science). Research reports are typical examples of grey literature. These works are often of the same quality as journal articles and should be taken into account in a comprehensive systematic literature review (Rothstein and Hopewell 2009).

References

Angermeyer, M. C., & Matschinger, H. (2003). The stigma of mental illness: effects of labelling on public attitudes towards people with mental disorder. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 108(4), 304–309. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.00150.x.

Arbour-Nicitopoulos, K. P., Faulkner, G. E., Paglia-Boak, A., & Irving, H. M. (2010). Adolescents‘ attitudes toward wheelchair users: A provincial survey. International Journal of Rehabilitation Research. Internationale Zeitschrift fur Rehabilitationsforschung. Revue internationale de recherches de readaptation, 33(3), 261–263. https://doi.org/10.1097/MRR.0b013e328333de97.

Blomqvist, J. (2009). What is the worst thing you could get hooked on?: Popular images of addiction problems in contemporary Sweden. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 26(4), 373–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/145507250902600404.

Brown, K. L., & Russell, A. M. T. (2019). Exploration of intervention strategies to reduce public stigma associated with gambling disorder. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-019-09888-3.

Browne, M., Langham, E., Rawat, V., Greer, N., Li, E., & Rose, J., et al. (2016). Assessing gambling-related harm in Victoria: A public health perspective. Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. Retrieved December 9, 2020 from https://responsiblegambling.vic.gov.au/resources/publications/assessing-gambling-related-harm-in-victoria-a-public-health-perspective-69/

Browne, M., Rawat, V., Newall, P., Begg, S., Rockloff, M., & Hing, N. (2020). A framework for indirect elicitation of the public health impact of gambling problems. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09813-z.

Card, N. A., & Little, T. D. (Eds.). (2016). Applied meta-analysis for social science research. New York: The Guilford Press.

Carroll, A., Rodgers, B., Davidson T., & Sims, S. (2013). Stigma and help-seeking for gambling problems.

Chan, C. C., & Ohtsuka, K. (2011). All for the winner: An analysis of the characterization of male gamblers in hong kong movies with gambling theme. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 9(2), 208–218. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-010-9274-5.

Cooper, H., Hedges, L. V., & Valentine, J. C. (2009). Handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Crawford, J. R., Thomson, N. A., Gullion, F. E., & Garthwaite, P. (1989). Does endorsement of the disease concept of alcoholism predict humanitarian attitudes to alcoholics? International Journal of the Addictions, 24(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826088909047275.

Cunningham, J. A., Cordingley, J., Hodgins, D. C., & Toneatto, T. (2011). Beliefs about gambling problems and recovery: Results from a general population telephone survey. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27(4), 625–631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-010-9231-z.

Dhillon, J., Horch, J. D., & Hodgins, D. C. (2011). Cultural influences on stigmatization of problem gambling: East Asian and Caucasian canadians. Journal of Gambling Studies, 27(4), 633–647. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-010-9233-x.

Egerer, M. (2013). Problem drinking, gambling and eating – three problems, one understanding? A qualitative comparison between french and finnish social workers. Nordic Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, 30(1–2), 67–86. https://doi.org/10.2478/nsad-2013-0006.

Egerer, M., & Rantala, V. (2015). What makes gambling cool? Images of agency and self-control in fiction films. Substance Use and Misuse, 50(4), 468–483. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2015.977708.

Feeney, D. (2013). Public opinion and problem gambling. In: Gambling and Risk Taking Conference, Las Vegas.

Gavriel-Fried, B., & Rabayov, T. (2017). Similarities and differences between individuals seeking treatment for gambling problems vs. alcohol and substance use problems in relation to the progressive model of self-stigma. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 957. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00957.

Gay, J., Gill, P. R., & Corboy, D. (2016). Parental and peer influences on emerging adult problem gambling: Does exposure to problem gambling reduce stigmatizing perceptions and increase vulnerability? Journal of Gambling Issues, 1(33), 30. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2016.33.3.

Grunfeld, R., Zangeneh, M., and Grunfeld, A. (2004). Stigmatization dialogue: Deconstruction and content analysis. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 1.

Hing, N., Holdsworth, L., Tiyce, M., & Breen, H. (2013). Stigma and problem gambling: Current knowledge and future research directions. International Gambling Studies, 14(1), 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2013.841722.

Hing, N., Nuske, E., Gainsbury, S. M., & Russell, A. M. T. (2016b). Perceived stigma and self-stigma of problem gambling: Perspectives of people with gambling problems. International Gambling Studies, 16(1), 31–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2015.1092566.

Hing, N., Nuske, E., Gainsbury, S. M., Russell, A. M. T., & Breen, H. (2016a). How does the stigma of problem gambling influence help-seeking, treatment and recovery? A view from the counselling sector. International Gambling Studies, 16(2), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2016.1171888.

Hing, N., & Russell, A. M. T. (2017a). How anticipated and experienced stigma can contribute to self-stigma: The case of problem gambling. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 235. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00235.

Hing, N., & Russell, A. M. T. (2017b). Psychological factors, sociodemographic characteristics, and coping mechanisms associated with the self-stigma of problem gambling. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(3), 416–424. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.056.

Hing, N., Russell, A. M. T., & Gainsbury, S. M. (2016e). Unpacking the public stigma of problem gambling: The process of stigma creation and predictors of social distancing. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(3), 448–456. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.057.

Hing, N., Russell, A., Gainsbury, S., & Nuske, E. (2016d). The public stigma of problem gambling: its nature and relative intensity compared to other health conditions. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-015-9580-8.

Horch, J. D., & Hodgins, D. C. (2008). Public stigma of disordered gambling: social distance, dangerousness, and familiarity. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 27(5), 505–528. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2008.27.5.505.

Horch, J., & Hodgins, D. (2013). Stereotypes of problem gambling. Journal of Gambling Issues, 66(28), 1. https://doi.org/10.4309/jgi.2013.28.10.

Horch, J. D., & Hodgins, D. C. (2015). Self-stigma coping and treatment-seeking in problem gambling. International Gambling Studies, 15(3), 470–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2015.1078392.

Jones, E. E. (1984). Social stigma: The psychology of marked relationships. New York: Freeman.

Koski-Jännes, A., Hirschovits-Gerz, T., & Pennonen, M. (2012). Population, professional, and client support for different models of managing addictive behaviors. Substance Use and Misuse, 47(3), 296–308. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2011.629708.

Koski-Jännes, A., & Simmat-Durand, L. (2017). Basic beliefs about behavioural addictions among finnish and french treatment professionals. Journal of Gambling Studies, 33(4), 1311–1323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9672-8.

Lang, B., & Rosenberg, H. (2017). Public perceptions of behavioral and substance addictions. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 31(1), 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000228.

Leung, R. (2016). Representation of gamblers in the Singaporean press since C-A-S-I-N-O legalization: A corpus-driven critical analysis. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 5(6), 51–63. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.5n.6p.51.

Li, W., Tse, S., & Chong, M. D. (2014). Why Chinese international students gamble: Behavioral decision making and its impact on identity construction. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 12(3), 321–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-013-9456-z.

Liberati, A., Altman, D. G., Tetzlaff, J., Mulrow, C., Gøtzsche, P. C., Ioannidis, J. P. A., et al. (2009). The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000100. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000100.

Lopez-Gonzalez, H., Estévez, A., & Griffiths, M. D. (2018). Can positive social perception and reduced stigma be a problem in sports betting? A qualitative focus group study with spanish sports bettors undergoing treatment for gambling disorder. Journal of Gambling Studies, 35(2), 571. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9799-2.

Miller, H., & Thomas, S. (2017a). The problem with ‘responsible gambling’: Impact of government and industry discourses on feelings of felt and enacted stigma in people who experience problems with gambling. Addiction Research and Theory, 26(2), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1332182.

Miller, H. E., & Thomas, S. (2017b). The “walk of shame”: A qualitative study of the influences of negative stereotyping of problem gambling on gambling attitudes and behaviours. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 15(6), 1284–1300. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-017-9749-8.

Miller, H. E., & Thomas, S. L. (2018). The problem with ‘responsible gambling’: impact of government and industry discourses on feelings of felt and enacted stigma in people who experience problems with gambling. Addiction Research and Theory, 26(2), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2017.1332182.

Miller, H. E., Thomas, S. L., Robinson, P., & Daube, M. (2014). How the causes, consequences and solutions for problem gambling are reported in Australian newspapers: a qualitative content analysis. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public health, 38(6), 529–535. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12251.

Miller, H. E., Thomas, S. L., Smith, K. M., & Robinson, P. (2016). Surveillance, responsibility and control: An analysis of government and industry discourses about “problem” and “responsible” gambling. Addiction Research and Theory, 24(2), 163–176. https://doi.org/10.3109/16066359.2015.1094060.

Nerilee, H., Russell, A. M. T., Nuske, E., & Gainsbury, S. (2015). The stigma of problem gambling: Causes, characteristics and consequences.

Palmer, B. A., Richardson, E. J., Heesacker, M., & Kristina DePue, M. (2017). Public stigma and the label of gambling disorder: does it make a difference? Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9735-x.

Palmer, B. A., Richardson, E. J., Heesacker, M., & Kristina DePue, M. (2018). Public stigma and the label of gambling disorder: does it make a difference? Journal of Gambling Studies, 34(4), 1281–1291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-017-9735-x.

Peter, S. C., Li, Q., Pfund, R. A., Whelan, J. P., & Meyers, A. W. (2018). Public stigma across addictive behaviors: casino gambling, esports gambling, and internet gaming. Journal of Gambling Studies. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-018-9775-x.

Rockloff, M. J., & Schofield, G. (2004). Factor analysis of barriers to treatment for problem gambling. Journal of gambling studies, 20(2), 121–126. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JOGS.0000022305.01606.da.

Rosenthal, R. (2010). Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Newbury Park: Sage Publ.

Rothstein, H. R., & Hopewell, S. (2009). Grey Literature. In H. M. Cooper, L. V. Hedges, & J. C. Valentine (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (pp. 103–125). New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

Schomerus, G. (2017). Das Stigma von Suchterkrankungen verstehen und überwinden. Psychiatrische Praxis, 44(5), 249–251. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0043-109924.

Schomerus, G., & Rumpf, H.-J. (2017). Das Stigma von Suchterkrankungen muss überwunden werden. SUCHT, 63(5), 251–252. https://doi.org/10.1024/0939-5911/a000500.

Sulkunen, P. (2007). Images of addiction: Representations of addictions in films. Addiction Research and Theory, 15(6), 543–559. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066350701651255.

Thege, K., Barna, I. C., el-Guebaly, N., Hodgins, D. C., Patten, S. B., Schopflocher, D., et al. (2015). Social judgments of behavioral versus substance-related addictions: a population-based study. Addictive behaviors, 42, 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.025.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Human and Animal Rights

This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wöhr, A., Wuketich, M. Perception of Gamblers: A Systematic Review. J Gambl Stud 37, 795–816 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-020-09997-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10899-020-09997-4