Abstract

Purpose

Childhood exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) is a pervasive problem worldwide. In addition to directly observing or indirectly experiencing IPV, children may be killed because of IPV. To date, research on child IPV-related deaths exists in various, disconnected areas of scholarship, making it difficult to understand how IPV contributes to child fatalities. As such, this scoping review located and synthesized research on child fatalities that resulted from IPV, seeking to understand the state of global research concerning the prevalence and circumstances of IPV-related child fatalities.

Methods

Using a combination of keywords and subject terms, we systematically searched PsycINFO, CINAHL Plus, PubMed, and seven research repositories. We located empirical studies published in English in peer-reviewed journals that reported findings concerning children (aged 0–17) who were killed because of IPV and/or people who killed children due to IPV. Among 9,502 de-duplicated records, we identified 60 articles that met review inclusion criteria. We extracted and synthesized information concerning research methods, circumstances and consequences of the fatalities, characteristics of people who committed IPV-related homicide of a child, and characteristics of children who died because of IPV.

Results

Studies were published from 1986–2022 and analyzed data from 23 countries. Most studies did not focus exclusively on IPV-related child homicides, and overall, studies reported sparse information concerning the contexts and circumstances of such fatalities. There were two predominant and distinct groups of children killed due to IPV: children killed by a parent or other adult caregiver and adolescents killed by an intimate partner. It was often difficult to ascertain whether the demographic characteristics of individuals who kill a child in the context of IPV and other contextual details might be similar to or different from child fatalities that occur under different circumstances or for other motivations.

Conclusions

This review highlighted that children die because of IPV. Findings indicated that such fatalities, while maybe difficult to predict, are often preventable if earlier intervention is made available and professionals are alert to key circumstances in which fatality risk is high. Future research and practice efforts should attend to understanding child fatalities resulting from IPV to identify critical intervention points and strategies that will save children’s lives.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Characteristics of Child Fatalities that occur in the context of current or past Intimate Partner Violence: a Scoping Review

Childhood exposure to intimate partner violence (IPV) is a pervasive problem worldwide that increases the risk of chronic and severe behavioral and mental health problems across developmental periods (Finkelhor et al., 2015; Holt et al., 2008; Moylan et al., 2010). IPV includes sexual, physical, or psychological abuse or stalking within current or former intimate relationships (Niolon et al., 2017). IPV is a gendered phenomenon. Available research indicates that girls, women, and particularly transgender and gender diverse people are disproportionately harmed by IPV victimization compared to boys and men (e.g., Cunningham & Anderson, 2023; Peitzmeier et al., 2020). Children may be exposed to IPV by directly observing such abuse or indirectly experiencing it, such as by overhearing violent incidents or more generally being aware of IPV occurring around them (Kieselbach et al., 2022). Children may also die in the context of current or past IPV —a devastating and preventable outcome that is the focus of this scoping review.

Childhood IPV Exposure Prevalence and Consequences

Globally in low- and lower-middle-income countries, on average, an estimated 29% of children are exposed to IPV in their lifetimes (Kieselbach et al., 2022); similarly in the United States (US), a national study (2013–2014 data) estimated that more than 25% of children are exposed to IPV (Finkelhor et al., 2015). Notably, children exposed to IPV often also experience child maltreatment resulting from adult caregivers’ revenge against an intimate partner or caregivers’ inability to engage in safe, nurturing, and responsive parenting behaviors (Chiesa et al., 2018; Dekel et al., 2019). A recent systematic review found that the European prevalence rates of IPV and child maltreatment co-occurrence reported in nine studies (1999–2019) ranged from 10–90%, with most rates around 30%; past year prevalence rates for North American community samples were from 1–89%, with most from 10–30% (Sijtsema et al., 2020).

Evidence of high rates of IPV and child maltreatment co-occurrence have led to growing recognition of IPV’s wide-ranging negative impacts on children (Skafida et al., 2022). A strong evidence base demonstrates that IPV exposure, even as early as during the perinatal period (Mueller & Tronick, 2020), is associated with significant, harmful consequences for children’s well-being at the time of exposure and beyond; interruptions in typical development due to IPV exposure can lead to life-long implications. Studies have indicated that such consequences include but are not limited to children exhibiting mood and eating disturbances; delayed and atypical social, emotional, and behavioral development; problematic internalizing and externalizing behaviors; and additional responses associated with trauma exposure (Holt et al., 2008; Moylan et al., 2010; Mueller & Tronick, 2020; Weir et al., 2021). As the field’s attention to the impact of children’s experiences of IPV has developed, acknowledgement and understanding of the heterogeneity of such experiences has expanded. Evidence exists that impacts on children can be mediated by a range of factors including the child’s gender, the age at which they were first exposed to violent and controlling behavior, the length of time that they were exposed to such problematic behavior, and the nature of the experience itself (Holt et al., 2008; Moylan et al., 2010; Mueller & Tronick, 2020; Weir et al., 2021).

Research on Child Fatalities in the Context of Current or Past IPV

Regarding the nature of IPV exposure, over the past several decades some scholars have investigated the extreme end of the spectrum of IPV experienced by young people—fatalities that occur in the context of current or past IPV or, in other words, when there is evidence of current or past IPV experienced by a child or to which a child has been exposed that precipitated the child’s death (also referred to as “IPV-related child fatalities” in this paper). Although there is some research that examines IPV-related child fatalities, this literature is not well-developed and is often contained within somewhat disparate and siloed bodies of knowledge, such as child maltreatment literature (e.g., Chan et al., 2021; Frederick et al., 2019; Michaels & Letson, 2021); domestic/family homicide or familicide scholarship (e.g., Kim & Merlo, 2023; Truong et al., 2023); and IPV studies concerning corollary victimhood (e.g., Graham et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2014). Notably, several recent reviews have focused on synthesizing literature concerning domestic/family homicide (e.g., Kim & Merlo, 2023; Truong et al., 2023) and familicide (e.g., Boyd et al., 2022; Karlsson et al., 2021). Among these was an umbrella review (Kim & Merlo, 2023) that located 25 reviews published from 2010–2020 that focused on various aspects of domestic homicides, in a variety of countries, though primarily Western nations, including Western Europe and the US. Twelve of these reviews synthesized literature on intimate partner homicide (IPH) and IPH-suicide events involving adult and/or child fatalities. Eight of the reviews examined child homicide (within and outside of the IPV context). Among these eight, only two focused specifically on child fatalities in the context of “domestic homicide” (Jaffe et al., 2012) and “familicide” (Mailloux, 2014), with Jaffe et al. (2012) focused only on studies with US and Canadian samples and Mailloux (2014) conducting a non-systematic search of newspaper and journal articles to comment on possible reasons why children die in the context of familicide. Overall the aformentioned umbrella review demonstrated that research on IPV-related child fatalities shows up in various areas of scholarship that often do not cross-pollinate. Further, it supports our understanding that individual studies concerning the global prevalence and characteristics of IPV-related child fatalities that occur because of IPV have not yet been systematically located and synthesized across various bodies of literature to inform related research and practice efforts. Such synthesis is critical because it can elucidate how IPV contributes to child fatalities, which can in turn help identify potential intervention points and ways to prevent such child deaths. It may also help to improve understanding of whether there are particular risk factors in addition to IPV that indicate that children dying in the context of IPV are similar to, or different from, other child maltreatment deaths. Finally, as IPV services are generally designed for supporting adult victim-survivors of IPV, this effort can help guide the development of services that attend to the unique needs of children exposed to and at risk for dying in the context of IPV.

Current Study

This scoping review sought to systematically locate and synthesize existing global research on child fatalities (among those aged 0–17 years at the time of death) that occurred within the context of current or past abusive intimate relationships, including those ruled as homicides or otherwise legally categorized (e.g., suicide). Collating such evidence from across multiple bodies of literature has the potential to guide how the field conceptualizes the risks that exist in families experiencing IPV and how practitioners and the services they provide might bridge the gap between adult-focused and child-focused services that are widely used in formal support systems. This scoping review sought to answer the following primary research question: what is the state of global research concerning the prevalence and circumstances of child fatalities in the context of current or past IPV? More specifically, we attended to the data sources and research methods used to understand such child fatalities, circumstances in which such fatalities occurred, and the characteristics of child victims and those who killed children in the context of IPV. Given the nascent state of the research, as well as heterogeneity in the literature, we used a scoping review approach to systematically locate and synthesize this body of knowledge (Tricco et al., 2016).

Methods

This scoping review adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist (Tricco et al., 2018). We systematically identified and assessed peer-reviewed literature that analyzed and presented quantitative data concerning child fatalities that occurred in the context of IPV. We focused on peer-reviewed articles that reported quantitative information for this review because such articles were most likely to report prevalence information, a key focus of this effort, and to help ensure our ability to meaningfully synthesize information across a large number of articles. Our team followed a detailed review protocol developed by the authors that is available upon request; the protocol is not registered with an outside body.

To be included in this scoping review, articles had to: (1) be published in English in a peer-reviewed journal during or before December 2022; (2) analyze and report on primary or secondary quantitative data; and (3) report findings concerning children aged 0–17 years old who were killed in the context or as a result of current or past IPV and/or people who killed children aged 0–17 years in the context or as a result of current or past IPV. Books, book chapters, audio/visual media, case studies, systematic reviews, meta-analyses, and qualitative studies were excluded. Articles that did not break down and report data specific to children ages 0–17 were excluded.

To locate articles, a research librarian who consulted on our search strategy ran searches in PsycINFO, CINAHL Plus, and PubMed first in November 2019 and again in December 2022. A research team member also ran searches in seven research repositories in November 2019: ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global, Open Grey, National Resource Center on Domestic Violence publication, WorldCat Dissertations, National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) publication list, European Institute on Gender Equality, World Health Organization publications. These searches were not repeated in December 2022 due to the focus on peer-reviewed literature, which was better identified through database searches. No filters were used in the searches, except for a human subjects filter in PubMed. We used relevant subject headings in each database; an incomplete list includes homicide, child, infant, adolescent, parents, caregivers, and legal guardians (for a full database search strategy, see the Supplementary Materials). The three main concepts searched with a combination of keywords and subject terms were homicide, children, and perpetrators.

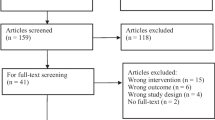

In database and repository searches, 9,834 results were exported to Covidence in 2019 and another 761 were exported in 2022 for a total of 10,595 records (see Fig. 1 for the PRISMA flow diagram). Before title and abstract screening, 1,093 duplicates were removed. At least two research team members independently reviewed each article title and abstract in Covidence. Conflicts in screening decisions were reviewed and resolved through consensus by at least three team members. At this stage, we excluded 8,491 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. Next, at least two team members independently reviewed the full texts of each remaining article, and they recorded their decisions in Covidence. Three senior research team members with extensive expertise concerning IPV and child fatalities reviewed full-text screening decisions and reached consensus on additional articles that should be excluded at this stage, leaving 131 articles for data extraction. During data extraction, an additional 71 articles were excluded due to insufficient information on the homicide sample, not being a peer-reviewed journal article, or because it was a duplicate of an article already located for inclusion. As such, this scoping review includes 60 articles.

The six team members who extracted data from articles followed a specific protocol developed prior to completing full-text reviews and initiating data extraction. They extracted data into an Excel template that they had piloted with multiple articles and refined based on this experience to increase data extraction consistency across extractors. One person extracted data from each article. For each article, a second team member independently reviewed extracted data and updated extracted data if needed to help ensure accuracy. Team members extracted data concerning research characteristics and methods, circumstances/context and consequences of the fatalities, characteristics of children who died in the context of current or past of IPV, and characteristics of people who committed homicide of a child in the context of current or past IPV. We then analyzed and synthesized data across articles in narrative form.

Results

This scoping review located 60 articles that reported quantitative and mixed methods research. These articles were published from 1986–2022 and reported research on child fatalities in the context of current or past IPV. Next, we report synthesized information on research characteristics and methods, contexts and circumstances in which IPV-related child fatalities occurred, characteristics of children who were killed or died because of current or past IPV, and characteristics of people who killed children in the context of current or past IPV. Overall, many of the articles reported information on multiple types of child fatalities—not only those that occurred in the context of IPV; typically, IPV-related child homicides or fatalities more generally were not the primary focus of the research. As such, it was often difficult to extract information specific to IPV-related child fatalities as opposed to child fatalities that occur under other circumstances or for other motivations.

Research Characteristics and Methods

Studies analyzed data from 23 countries, with six (10.0%) analyzing data from multiple countries (see Table 1, column 2 for countries for each article). Most frequently, article authors used data from the US (k = 23, 38.3%), followed by Europe (k = 21, 35.0%), Canada (k = 9, 15.0%), Australia (k = 7, 11.7%), Africa (k = 3, 5.0%), and Asia (k = 3, 5.0%). Across all articles, 42 (70.0%) reported only quantitative methods, and 18 (30.0%) reported mixed methods. Only one article reported the collection of primary data through an online survey (Douglas, 2013). Fifty-nine (98.3%) relied on secondary data, with many using multiple data sources (see Table 1, column 4 for details on data sources by article); the data sources reported by these articles included national surveillance data (k = 21; e.g., US National Violent Death Reporting System data); police/prison/crime/coroner’s records (k = 16); newspaper articles (k = 10); case files (k = 13); a specific data set (k = 5; e.g., Innocents Lost Database, National Suicide Prevention Project); and/or forensic/medical records (k = 3). Twenty-six (43.4%) reported on data collected after the year 2000 and 14 (23.3%) before 2000, with the remainder unspecified.

Articles focused on child and/or adult fatalities (e.g., homicides, suicides) that occurred in the context of a range of violence types, including “intimate partner,” “dating,” “domestic,” “family,” “marital,” and “spousal” violence, as well as “filicide,” “familicide,” and “femicide,” and these terms were defined differently across articles (see Table 1, column 3 for details on focal violence type by article). More than one-fifth (k = 13, 21.7%) of articles did not discuss specific case inclusion and exclusion criteria. Among those that did report such criteria, most commonly, articles included homicide-suicide or familicide-suicide (k = 16, 26.7%), filicide only (k = 12, 20.0%), and child homicide only cases (k = 11, 18.3%). Almost all child fatalities examined were identified as homicides. The exception to this trend were a small number of children who died by suicide (e.g., Adhia et al., 2019a examined homicide-suicides committed by adolescents). The number of child fatalities included in articles’ analytic samples was often difficult to discern due to insufficient or unclear reporting, precluding overall prevalence estimation in our review; this number ranged from 1 to at least 324.

Contexts and Circumstances in which IPV-related Child Fatalities Occurred

Overall, articles reported sparse information concerning the contexts and circumstances surrounding child fatalities that occurred in the context of IPV. A quarter of the articles (k = 15; 25.0%) reported some information on where the IPV-related child fatalities (generally homicides) occurred, and the level of detail on this topic varied. Among articles that reported data on the locations of the child fatalities, most child victims were killed in their own home, the home of the person who committed the homicide, or a home in which both the child victim and perpetrator lived. Overall, fewer occurred in public places (Adhia et al., 2019a, b;Cooper & Eaves, 1996; Fowler et al., 2017). The setting might vary by type of violent death (e.g., homicide versus homicide-suicide; Cooper & Eaves, 1996; Flynn et al., 2016) and/or the age of the victim (e.g., young children versus older children; Fowler et al., 2017). Five articles explicitly reported that the majority (> 50.0%) of cases included in the study took place in the victim’s home, although sometimes it was unclear whether “victim” referred to child and/or adult victims in cases involving multiple deaths (Adhia et al., 2019c; Ferrara et al., 2015; Lyons et al., 2021a, b; Tosini, 2017). One article stated that the majority of cases (91.0% of filicide cases examined) took place in the perpetrator’s home (Bourget & Gagné, 2005), and another article specified that in 19 out of 20 familicide cases reviewed, the “ … crime scene was the family home” (Frei & Ilic, 2020; p. 4). Additionally, one article reported that in all but one instance (of 26), the homicide took place either in the child victim’s or perpetrator’s home (Cavanagh et al., 2007).

Nearly two-thirds (k = 38, 63.3%) of all articles reported some information about the intimate relationship status (e.g., current versus former intimate partner and/or relationship type such as boyfriend/girlfriend, cohabiting, spouse) between the person who committed homicide and the person with whom they were in an abusive partnership. However, in multiple articles, it was unclear if the status reported was specific to the abusive relationship (e.g., the article reported that the perpetrator was married at the time of the homicide, but it was unclear if they were married to the person they killed or someone else). Details on this topic varied across articles at least in part due to variations in study aims, types of cases examined (e.g., familicide, filicide, IPV-related deaths), and how the studies defined relationship type or status. Most commonly, articles reported that the largest proportion of partners in an abusive relationship in their sample were married, or more generally, that the perpetrator was married at the time of the homicide (k = 13). Ten articles reported that the largest proportion were in current relationships, with one article explicitly noting that just over half of the IPV-related cases in their sample involved currently married partners (Alexandri et al., 2022). Four articles reported that the largest proportion were cohabiting at the time of the violent death(s) (Cavanagh et al., 2007; Dobash & Dobash, 2012; Flynn et al., 2016; Kauppi et al., 2010), and two of these articles explicitly described that these individuals were both cohabiting and married (Flynn et al., 2016; Kauppi et al., 2010). Though not always clear, most articles appeared to focus on mixed-sex/heterosexual partnerships, most of them reporting on child and adult fatalities that resulted from IPV committed by men against women. A minority of articles specifically addressed separation and/or divorce (e.g., Brown et al., 2014; Cooper & Eaves, 1996; El-Hak et al., 2009; Frei & Ilic, 2020). For example, Cooper and Eaves (1996) found that nearly one-third of the homicide victims in their study who were killed following marital separation were children who were murdered by their fathers. Although we sought to extract data on whether a child victim was living with the person who killed them at the time of death, we found that no articles reported clear information on this topic.

More than half of articles (k = 37, 61.7%) reported some information on the timing (e.g., past, present, ongoing) of IPV (also called domestic, family, or marital violence) experienced by any portion of their samples. In some articles it was unclear whether this history of violence was with a partner and associated child who was killed or a different relationship unconnected to the homicide(s) included in the research (e.g., Ferrara et al., 2015; Flynn et al., 2016). Though the details varied, collectively, the articles indicated past and/or ongoing IPV precipitated some portion of violent child deaths and should be attended to as a risk factor for such deaths; however, it was not possible to estimate how commonly IPV precipitated child homicides from this sample of articles and our review. Five of the 37 articles reported that in most of their sample, IPV between parents was present prior to and/or at the time of the child homicides (Adhia et al., 2019a, c; Bush, 2020; Cavanagh et al., 2007; Dobash & Dobash, 2012). Among articles that did not focus exclusively on cases involving IPV, a few mentioned that their estimate of the presence of IPV is likely an underestimation (e.g., Brown et al., 2014; Dawson, 2015). Some articles also reported on familial behaviors that might or might not constitute IPV but precipitated child homicides (e.g., heated arguments between parents; e.g., Eke et al., 2015; El-Hak et al., 2009). Also, as noted by Dobash and Dobash (2012), it might have been hard for study authors to disentangle violence that was directed toward children and that toward adult partners.

Less than half of articles (k = 25, 41.7%) reported data on precipitating circumstances or motivations for IPV-related child fatalities, although we could not always identify when such motivations or circumstances were specific to incidents that involved child fatalities and/or other cases included in each study (see Table 1, column 5 for more information on this topic). Across articles, four such reasons commonly surfaced. First and most often, multiple articles described revenge/jealousy as a motivation for such fatalities, including having suspicion of extramarital affairs, jealousy concerning a new partner, or related issues toward (most often female) partners (Adhia et al., 2019b; Adinkrah, 2001; Alexandri et al., 2022; Dawson, 2015; Graham et al., 2021; Myers et al., 2021); jealousy or resentment toward women because of their attention on children (Dobash & Dobash, 2012); or unspecified jealousy (Alexandri et al., 2022; Bush, 2020; Ferrara et al., 2015; Moen & Bezuidenhout, 2023; Shiferaw et al., 2010). Second, some articles highlighted economic concerns or financial trouble as a potential motivation for such child fatalities (Alexandri et al., 2022; Chan & Beh, 2003; El-Hak et al., 2009; Ferrara et al., 2015; Flynn et al., 2016; Saleva et al., 2007). Third, a few articles discussed separation/break-up and divorce from a partner or termination of sexual relations as potential motivation for these child fatalities (Adhia et al., 2019a, b; Chan & Beh, 2003; Cooper & Eaves, 1996; Ferrara et al., 2015; Flynn et al., 2016; Frei & Ilic, 2020; Holland et al., 2018; Saleva et al., 2007; Shiferaw et al., 2010). Fourth, mental health issues or mental illness, sometimes including substance abuse, were identified among potential motivations or precipitating circumstances in multiple articles (Cooper & Eaves, 1996; Ferrara et al., 2015; Flynn et al., 2016; Frei & Ilic, 2020; Holland et al., 2018; Jonson-Reid et al., 2023; Jordan & McNiel, 2021).

Characteristics of Children who were Killed or Died in the Context of IPV

Additionally, we sought to identify key characteristics of children who were killed or died in the context of IPV. Among articles reviewed, there were two predominant and distinct groups—children killed by a parent or other adult caregiver; and adolescents killed by an intimate partner. Most articles (k = 34, 56.6%) found that murdered children were either biological or stepchildren of the person who killed them, with the larger proportion being biological children. For example in one study, 95% of the child victims were biological children and 5.0% stepchildren of the person who killed them (Barnes, 2000). In another study, 89.0% were biological children and 11.0% stepchildren of the person who killed them (Sillito & Salari, 2011). In Wilson et al. (1995), 89.3% of child victims from Canada were biological children and 10.2% stepchildren of the person who killed the children, and 83.1% of child victims from the United Kingdom were biological children and 16.9% stepchildren of the person who killed them.

Studies investigated a variety of different types of cases, including incidents involving one or multiple fatalities. In studies that investigated cases in which there were multiple deaths of children and adults, frequently, these incidents involved a male perpetrator killing their adult female intimate partner together with one or more people under age 18 (e.g., Abolarin et al., 2019; Barnes, 2000; Bourget & Gagné, 2005). Further, in many situations in which children were killed, violence was also used against female intimate partners (e.g., Cavanagh et al., 2007; Dobash & Dobash, 2012). Notably, Daly and Wilson (1994) found that men who killed their biological children were also more liable time than men who killed their stepchildren to kill their spouses at the same time (p < 0.05).

Across articles, child victims’ ages ranged from 0 to 19 years. A variety of age ranges were found in different articles (e.g., 0–11 in Cheung, 1986; 0–5 in Daly & Wilson, 1994; 5–19 years in Moskowitz et al., 2005); however ‘under 18 years of age’ was common among those that reported age (e.g., Brown et al., 2014; Messing & Heeren, 2004; Morton, 1998). Regarding the potential influence of age on risk for child fatality, Brown et al. (2014) suggested that an older age might protect against child homicide victimization given that over one-third of child victims in their study were under the age of 4 years. Relatedly, child homicide by biological mothers often occurred in the first 12 months after childbirth and among those aged 3 to 6 years old at the time of death (e.g., Cheung, 1986; Eke et al., 2015).

Regarding child victim sex, findings were mixed. Out of the 18 (30.0%) articles that reported the sex distribution of child victims within their samples, 10 indicated a majority (> 50.0%) of male victims, while six indicated a majority (> 50.0%) of female victims (Adhia et al., 2019a, b; Alexandri et al., 2022; El-Hak et al., 2009; Lyons et al., 2021a; Tosini, 2017). Additionally, in two articles, the sex distribution was evenly split (Cavanagh et al., 2007; Frei & Ilic, 2020). Notably, several of these articles reported similar proportions between females and males (Abolarin et al., 2019; El-Hak et al., 2009; Lyons et al., 2021a, b; Moen & Bezuidenhout, 2023). For example, El-Hak et al. (2009) reported that about 48.0% were male and 52.0% female, with no statistically significant difference in sex. On the other hand, several studies found larger differences. Brown et al. (2014) found that child victims killed by adults were more often male (70.0%) than female (30.0%), as did Douglas (2013) with 65.2% male and 34.9% female. Additionally, in multiple articles (k = 13, 21.7%), the sample included adolescents under age 18 who were in abusive intimate relationships with the person who killed them (e.g., Adhia et al., 2019b; Bush, 2020; Graham et al., 2021; Mathews et al., 2019; McLachlan & Harris, 2022; Moskowitz et al., 2005). Among articles that reported details about child victim sex, child victims killed by their dating or intimate partners were largely female adolescents. For example, Adhia et al., (2019b) found that of the 2,188 homicides of children aged 11–18 years, 150 (6.9%) were classified as IPH, of whom 90.0% (n = 135) were female. Other information, including child victims’ race, ethnicity, and education level, was not considered in most articles reviewed.

Characteristics of People Who Killed Children in the Context of IPV

As previously noted, many articles reported information on multiple types of child homicides—not only those that were the result of IPV-related. As such, it was often difficult to ascertain whether the demographic characteristics of individuals who kill a child in the context of IPV and other contextual details might be similar to or different from child fatalities that occur under different circumstances or for other motivations. Across all articles (k = 34, 56.7%) that looked at deaths caused by both men and women, in all but one article (Putkonen et al., 2011) the majority of child fatalities in the context of current or past IPV were caused by men, ranging from between 36.3–95.5% of such fatalities. Drawing upon the Statistics Canada’s annual Homicide Survey, Dawson (2015) found fathers were more commonly the accused in cases involving a history of family violence compared to mothers by almost four to one (79.0% to 21.0%, respectively).

In their study using the US National Violent Death Reporting System for 2003–2015, Abolarin et al. (2019) identified 2,425 homicide incidents involving multiple victims, of which 741 were intimate partners or family members of the victims. Overall, the most common pattern in these incidents was a male offender who killed their intimate partner as well as one or more children (182 incidents, 24.6% of incidents examined). A similar pattern emerged over a period of 20 years (1973–1992) across five Australian states where 73 children were killed by a parent (55 children killed by their father) who then died by suicide. This represented 73 deaths of children in the context of murder-suicides in 188 incidents during this period (Barnes, 2000).

In their study of IPHs of adolescents, Adhia et al., 2019b analyzed data from the US National Violent Death Reporting System for 2003–2016. Overall, 134 (89.9%) of those who committed homicide were male, with 15 female (10.1%). One hundred and two people who killed their current or former intimate partners (77.9%) were aged 18 years and older (M = 20.6 years; SD = 5.0 years), and 94 (62.7%) were current intimate partners of the victim. Those who committed homicide were more likely to be Black and non-Hispanic (48.2%) or White and non-Hispanic (31.2%), compared to victims who were most likely White and non-Hispanic (42%) or Black and non-Hispanic (40.7%).

Relationship to the Child

Articles captured by this review indicated that for child homicide in the context of IPV, there were three distinct groups of individuals who caused harm. First, the largest group were men who were current or former intimate partners of a child’s mother, either biologically related to the child or not, who harmed the child (k = 56, 93.3%). Next, there was a smaller group of women who were current or former intimate partners of a child’s father, either biologically related to the child or not, who harmed the child (k = 11, 18.3%; Adhia et al., 2019c; Cavanagh et al., 2007; Dawson, 2015; Ferrara et al., 2015; Logan-Greene et al., 2013). Finally, as indicated previously, studies demonstrated that female adolescents are at times killed by their current or former male intimate partner (k = 13, 21.6%; e.g., Adhia et al., 2019a, b; Ferrara et al., 2015; Meyer & Post, 2013; Nielssen et al., 2009).

Method of Death

Barnes (2000) noted that men who killed were more likely to use more violent ways of committing both murder and suicide. Notably, most studies were undertaken in national contexts with wide ownership or access to firearms. As such, many of the deaths in the articles reviewed were caused by firearm injuries (k = 7, 11.7%; Abolarin et al., 2019; Adhia et al., 2019b, c; Bourget & Gagné, 2005; Byard et al., 1999; Dawson, 2015; Sillito & Salari, 2011), including the deaths of adolescents under age 18 years killed by their current or former intimate partner (Adhia et al., 2019b). Drawing upon the North Carolina Violent Death Reporting System for 2004–2013, Smucker et al. (2018) highlighted that for men who killed, IPH with a gun averaged 1.58 victims, compared with 1.14 victims in IPH with other weapons (p < 0.001). This pattern was much less pronounced for women, where IPHs committed with firearms had just 1.09 victims, compared with 1.01 victims for non-firearm cases (p < 0.10).

In contexts with less access to firearms, stabbing with a sharp implement, strangulation and blunt trauma were the most common methods used (Chan & Beh, 2003; El-Hak et al., 2009; Ferrara et al., 2015). However, for most of these studies, the distinction between children killed in the context of IPV from more general child homicide was unclear, apart from instances where the current or former adult intimate partner was killed as well as the child.

Homicide-Suicide

Multiple articles indicated that some portion of people who committed homicide died by suicide after they murdered one or more children and often other family members (Barber et al., 2008; Barnes, 2000; Ferrara et al., 2015; Saleva et al., 2007; Shiferaw et al., 2010; Smucker et al., 2018). Abolarin et al. (2019) highlighted that suicide following homicide increases with the increasing number of homicide victims, with Wilson et al. (1995) reporting that the incidence of suicide in familicides substantially and significantly exceeds that in non-familicidal, IPHs only, and filicides. For those who killed a current or former intimate partner under 18 years, 16.0% (n = 24) of them died by suicide (Adhia et al., 2019b).

Characteristics of the Perpetrators’ Personal History

Many of the articles (k = 50; 83.3%) included some information on the background of adults who had killed children, including adversity experienced in childhood (e.g., Cavanagh et al., 2007; Cheung, 1986), prior criminal convictions (e.g., Cavanagh et al., 2007; Dobash & Dobash, 2012), and history of mental illness and/or problematic substance use (e.g., Bourget & Gagné, 2005; Brown et al., 2014; Flynn et al., 2016). However, this information was generally not disaggregated for children who died in the context of IPV.

Context

Notably, in many of these fatal assaults the child victim was in the sole care of the person who killed them, mothers having left fathers with temporary responsibility for the care of the child. The data from Cavanagh et al. (2007) indicated some men appeared unable or unwilling to discharge their limited parenting responsibilities without enacting violence. Findings suggested that violence seemed to be a preferred choice for many who killed children, and trial judges highlighted their propensity to use violence to resolve problems. Alternatively, Sillito and Salari (2011) highlighted that an estranged relationship between parents may actually be a protective factor for child survival, especially if the child spent time with a parent in another household.

Discussion

This scoping review sought to systematically locate and synthesize existing global research on child fatalities (among those aged 0–17 years at the time of death) that have occurred within the context of current or former abusive intimate relationships, including those ruled as homicides or otherwise legally categorized. In doing so, we sought to identify what is known about such deaths, and what is still unclear, to characterize the state of global research concerning the prevalence and circumstances of IPV-related child fatalities.

In our review, we identified several key themes and points of learning. First, to better understand and describe the prevalence and circumstances in which children die in the context of IPV, we need to distinguish between the deaths of young people who are killed or die by suicide within their own intimate relationships and child fatalities that occur in the context of IPV among adults who are responsible for caring for those children. Recognizing these distinct groupings has the potential to ensure that policy and practice responses aimed at both prevention and intervention are sensitive to the specific context and needs of each group. However, to date, only a few studies have adopted this approach (e.g., Adhia et al., 2019a, b and address IPV-related homicides and suicides among adolescents; Adhia et al., 2019c examines deaths among children ages 2–14 who die in the context of IPV among parents).

Second and relatedly, this review demonstrates that the existing literature that paid attention specifically to IPV-related child fatalities is very limited; most studies identified did not aim to conduct investigations of these deaths specifically, making prevalence estimation impossible. Research has tended to treat children who die in the cxontext of IPV as either collateral victims of adult IPV (e.g., Graham et al., 2021); or to merge the deaths of children in the context of IPV with the wider pool of deaths resulting from child maltreatment or homicide more broadly (e.g., Cavanagh et al., 2007). However, in doing so, the deaths of children in the context of IPV are less likely to be identified and treated as a primary research focus on their own. This lack of targeted research hinders our understanding of the unique dynamics surrounding IPV-related child fatalities. Accordingly, conducting such investigations would help ascertain what professional and service responses are required to support these children and address their distinct needs. In the United Kingdom and elsewhere, there is growing acceptance that not only are children victim-survivors of IPV but that their experiences and needs may differ from that of adult victim-survivors (e.g., Giesbrecht et al., 2023). Conversely, systemic responses to managing the risks of IPV for children needs to attend to the most appropriate and effective ways to work with the child’s safe parent/caregiver (Hale et al., 2024), as well as account for the benefits of the child-mother relationship in terms of being protected and nurtured in both the immediate- and long-term (Skafida & Devaney, 2023).

Research, Practice, and Policy Implications

Several implications arise from these findings. Our review covered studies undertaken across five decades. As such, it is unsurprising that terminology and concepts have changed over such a lengthy period. However, it is also clear that time alone cannot explain the diversity of terms used to refer to deaths of adults and children resulting from various forms of familial violence. Greater consistency and transparency in how deaths are defined, along with the adoption of an agreed core dataset or set of indicators that reflects current theoretical frameworks and empirical findings related to deaths of children in the context of IPV would allow for greater pooling and comparison of data between and across studies, contexts, and countries. Such efforts would increase the potential to then explore the intra-group commonalities and differences of sub-groups of children, such as comparisons between those killed in the context of family separation and those killed due to other motivations or under other circumstances. One promising example of such a dataset that is being used to study IPV-related deaths among young people is the National Violent Death Reporting System, a surveillance system that captures a wide array of data on violent deaths among individuals of all ages across all US states, districts, and territories. Though not without limitations and flaws (see AbiNader et al., 2023), national surveillance systems of this type can shed light on the circumstances in which children die in the context of of IPV. There is clearly need for additional studies that focus specifically on the IPV-related child fatalities, and to develop methodologies that gather quantifiable, comparable data alongside qualitative studies that seek to understand such incidents.

Additionally, several current practice and policy discourses align with and are supported by our findings. There is increasing recognition that young people may experience IPV or even homicide in their dating relationships, need focused support to recognize the harm they are experiencing and/or causing, and would likely benefit from having tailored support (Bundock et al., 2020; Debnam & Kumodzi, 2021). Such discourses and findings from this review further demonstrate the need to engage young people in programs that seek to reduce and prevent the incidence of adolescent dating violence (Reyes et al., 2021) and explore the ways in which IPV among adolescents contributes to homicide and suicide mortality (Graham et al., 2022; Kafka et al., 2023). Further, the field is beginning to acknowledge that children can be victims of and harmed by parental/caregiver IPV and need to be included in discussions about related service responses (Turner et al., 2017). Relatedly, the field is also more deeply examining whether and how to approach children’s experiences of parental/caregiver IPV as potential child maltreatment, an area deserving of careful attention to contexts and systems of care, with input from those with lived experience and professionals from across disciplines and service sectors. A recent systematic review (Lewis et al., 2018) of research on child, parent, and professional perspectives concerning child IPV exposure identification and early response highlights the need for such processes to be trauma-informed and tailored to the specific dynamics and presentation of IPV. Others have underscored the importance of taking great care in such processes to ensure that the victim parent is not placed at greater risk or otherwise harmed by being made responsible for the risk posed to children by their partner’s behavior (Hale et al., 2024).

Strengths and Limitations

This review is the first to systematically search for and synthesize existing quantitative literature concerning child fatalities in the context of IPV. The study has benefitted from a rigorous approach to searching and analyzing the relevant literature. However, this review is not without limitations. Had the study included a wider range of literature types, including work published in other languages and using qualitative designs, our understanding of these issues may have been fuller. The field would benefit from future reviews that identify and collate qualitative research, non-peer reviewed reports/documents, and literature written in languages other than English to assist with creating an even more comprehensive understanding of the state of global research on this topic, particularly given that culture and place have significant implications for how IPV is defined and manifests (e.g., Sokoloff & Dupont, 2005). Additionally, it is possible that we missed or misinterpreted some details in the large body of research reviewed; however, our rigorous approach that employed a protocol, multiple reviewers, and research team with a depth and range of IPV-related research and practice experience helped address this potential issue.

Conclusion

This review has highlighted that children die in the context of of IPV. There is a danger of viewing these deaths as the result of extreme violent incidents; however, the literature we reviewed demonstrates that IPV and related death of children and others is often the most extreme culmination of a much longer pattern of violence, abuse, and coercive control that adult and child victims commonly have been living with for some time. Therefore, such deaths, while maybe difficult to predict, are often preventable if earlier intervention is made available and professionals are alert to key circumstances in which risk may increase significantly, such as before and after periods of separation or in high conflict disputes about child contact. Future research and practice efforts should attend very specifically to understanding IPV-related child fatalities to identify critical intervention points and strategies that will save children’s lives.

Data Availability

The data underpinning this paper is available as a supplemental file.

References

*indicates an article included in this scoping review

AbiNader, M. A., Graham, L. M., & Kafka, J. M. (2023). Examining intimate partner violence-related fatalities: Past lessons and future directions using U.S. national data. Journal of Family Violence, 38(6), 1243–1254. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00487-2

Abolarin, J., McLafferty, L., Carmichael, H., & Velopulos, C. G. (2019). Family can hurt you the most: Examining perpetrators in multiple casualty events. Journal of Surgical Research, 242, 172–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2019.04.018

*Adhia, A., DeCou, C. R., Huppert, T., & Ayyagari, R. (2019a). Murder–suicides perpetrated by adolescents: Findings from the National Violent Death Reporting System. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, 50(2), 534-544. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12607

*Adhia, A., Kernic, M. A., Hemenway, D., Vavilala, M. S., & Rivara, F. P. (2019b). Intimate partner homicide of adolescents. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(6), 571–577. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.0621

*Adhia, A., Austin, S. B., Fitzmaurice, G. M., & Hemenway, D. (2019c). The role of intimate partner violence in homicides of children aged 2–14 years. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 56(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.08.028

*Adinkrah, M. (2001). When parents kill: An analysis of filicides in Fiji. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 45(2), 144–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X01452002

*Alexandri, M., Tsellou, M., Antoniou, A., Skliros, E., Koukoulis, A. N., Bacopoulou, F., & Papadodima, S. (2022). Prevalence of homicide-suicide incidents in Greece over 13 years. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(13), Article 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19137736

*Barber, C. W., Azrael, D., Hemenway, D., Olson, L. M., Nie, C., Schaechter, J., & Walsh, S. (2008). Suicides and suicide attempts following homicide: Victim–suspect relationship, weapon type, and presence of antidepressants. Homicide Studies, 12(3), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767908319597

*Barnes, J. (2000). Murder followed by suicide in Australia, 1973-1992: A research note. Journal of Sociology, 36(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/144078330003600101

*Bourget, D., & Gagné, P. (2005). Paternal filicide in Québec. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 33(3), 354–360.

Boyd, C., Sutton, D., Dawson, M., Zecha, A., Poon, J., Straatman, A.-L., & Jaffe, P. (2022). Familicide in Canada, 2010 to 2019. Homicide Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/10887679221097626

*Brown, T., Tyson, D., & Arias, P. F. (2014). Filicide and parental separation and divorce. Child Abuse Review, 23(2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2327

Bundock, K., Chan, C., & Hewitt, O. (2020). Adolescents’ help-seeking behavior and intentions following adolescent dating violence: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 21(2), 350–366. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018770412

*Bush, A. (2020). A multi-state examination of the victims of fatal adolescent intimate partner violence, 2011-2015. Journal of Injury and Violence Research, 12(1), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.5249/jivr.v12i1.1197

*Byard, R. W., Knight, D., James, R. A., & Gilbert, J. (1999). Murder-suicides involving children: A 29-year study. The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology, 20(4), 323–327. https://doi.org/10.1097/00000433-199912000-00002

*Cavanagh, K., Dobash, R. E., & Dobash, R. P. (2007). The murder of children by fathers in the context of child abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(7), 731–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.016

*Chan, C. Y., & Beh, S. L. (2003). Homicide-suicide in Hong Kong, 1989-98. Forensic Science International, 137, 165-171. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0379-0738(03)00350-5

Chan, K. L., Chen, Q., & Chen, M. (2021). Prevalence and correlates of the co-occurrence of family violence: A meta-analysis on family polyvictimization. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(2), 289–305. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019841601

*Cheung, P. T. K. (1986). Maternal filicide in Hong Kong, 1971–85. Medicine, Science and the Law, 26(3), 185–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/002580248602600303

Chiesa, A. E., Kallechey, L., Harlaar, N., Ford, C. R., Garrido, E. F., Betts, W. R., & Maguire, S. (2018). Intimate partner violence victimization and parenting: A systematic review. Child Abuse & Neglect, 80, 285–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2018.03.028

*Comstock, R. D., Mallonee, S., Kruger, E., Rayno, K., Vance, A., & Jordan, F. (2005). Epidemiology of homicide-suicide events: Oklahoma, 1994–2001. The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology, 26(3), 229–235. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.paf.0000160681.40587.d3

*Cooper, M., & Eaves, D. (1996). Suicide following homicide in the family. Violence and Victims, 11(2), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.11.2.99

Cunningham, M., & L. Anderson, K. (2023). Women experience more intimate partner violence than men over the life course: Evidence for gender asymmetry at all ages in a national sample. Sex Roles, 89(11), 702–717. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-023-01423-4

*Daly, M., & Wilson, M. I. (1994). Some differential attributes of lethal assaults on small children by stepfathers versus genetic fathers. Ethology and Sociobiology, 15(4), 207–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/0162-3095(94)90014-0

*Dawson, M. (2015). Canadian trends in filicide by gender of the accused, 1961–2011. Child Abuse & Neglect, 47, 162–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.07.010

Debnam, K. J., & Kumodzi, T. (2021). Adolescent perceptions of an interactive mobile application to respond to teen dating violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(13–14), 6821–6837. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518821455

Dekel, B., Abrahams, N., & Andipatin, M. (2019). Exploring the intersection between violence against women and children from the perspective of parents convicted of child homicide. Journal of Family Violence, 34, 9–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-018-9964-5

*Dobash, R. P., & Dobash, R. E. (2012). Who died? The murder of collaterals related to intimate partner conflict. Violence Against Women, 18(6), 662–671. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801212453984

*Douglas, E. M. (2013). Case, service and family characteristics of households that experience a child maltreatment fatality in the United States. Child Abuse Review, 22(5), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2236

*Eke, S. M., Basoglu, S., Bakar, B., & Oral, G. (2015). Maternal filicide in Turkey. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 60, S143–S151. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.12560

*El-Hak, S. A. G., Ali, M. A., & El-Atta, H. M. A. (2009). Child deaths from family violence in Dakahlia and Damiatta Governorates, Egypt. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 16(7), 388–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2009.04.010

*Ferrara, P., Caporale, O., Cutrona, C., Sbordone, A., Amato, M., Spina, G., Ianniello, F., Fabrizio, G. C., Guadagno, C., Basile, M. C., Miconi, F., Perrone, G., Riccardi, R., Verrotti, A., Pettoello-Mantovani, M., Villani, A., Corsello, G., & Scambia, G. (2015). Femicide and murdered women’s children: Which future for these children orphans of a living parent? Italian Journal of Pediatrics, 41(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13052-015-0173-z

Finkelhor, D., Turner, H. A., Shattuck, A., & Hamby, S. L. (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: Results from the national survey of children’s exposure to violence. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(8), 746–754. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0676

*Flynn, S., Gask, L., Appleby, L., & Shaw, J. (2016). Homicide–suicide and the role of mental disorder: A national consecutive case series. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 51(6), 877–884. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-016-1209-4

*Fowler, K. A., Dahlberg, L. L., Haileyesus, T., Gutierrez, C., & Bacon, S. (2017). Childhood firearm injuries in the United States. Pediatrics, 140(1), e20163486. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-3486

Frederick, J., Devaney, J., & Alisic, E. (2019). Homicides and maltreatment-related deaths of disabled children: A systematic review. Child Abuse Review, 28(5), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2574

*Frei, A., & Ilic, A. (2020). Is familicide a distinct subtype of mass murder? Evidence from a Swiss national cohort. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 30(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.2140

*Fujiwara, T., Barber, C., Schaechter, J., & Hemenway, D. (2009). Characteristics of infant homicides: Findings from a U.S. multisite reporting system. Pediatrics, 124(2), e210–e217. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3675

Giesbrecht, C. J., Kikulwe, D., Watkinson, A. M., Sato, C. L., Este, D. C., & Falihi, A. (2023). Supporting newcomer women who experience intimate partner violence and their children: Insights from service providers. Affilia, 38(1), 127–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/08861099221099318

*Graham, L. M., Ranapurwala, S. I., Zimmer, C., Macy, R. J., Rizo, C. F., Lanier, P., & Martin, S. L. (2021). Disparities in potential years of life lost due to intimate partner violence: Data from 16 states for 2006–2015. PLOS ONE, 16(2), e0246477. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0246477

Graham, L. M., Kafka, J. M., AbiNader, M. A., Lawler, S. M., Gover-Chamlou, A. N., Messing, J. T., & Moracco, K. E. (2022). Intimate partner violence–related fatalities among US youth aged 0–24 years, 2014–2018. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 62(4), 529–537. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.09.018

Hale, H., Bracewell, K., Bellussi, L., Jenkins, R., Alexander, Devaney, J., & Callaghan. (2024). The child protection response to domestic violence and abuse: A scoping review of interagency interventions, models and collaboration. Journal of Family Violence.

*Harris, G. T., Hilton, N. Z., Rice, M. E., & Eke, A. W. (2007). Children killed by genetic parents versus stepparents. Evolution and Human Behavior, 28(2), 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.08.001

*Holland, K. M., Brown, S. V., Hall, J. E., & Logan, J. E. (2018). Circumstances preceding homicide-suicides involving child victims: A qualitative analysis. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 33(3), 379–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515605124

Holt, S., Buckley, H., & Whelan, S. (2008). The impact of exposure to domestic violence on children and young people: A review of the literature. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(8), 797–810. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.02.004

Jaffe, P. G., Campbell, M., Hamilton, L. H., & Juodis, M. (2012). Children in danger of domestic homicide. Child Abuse and Neglect, 36(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.06.008

*Jonson-Reid, M., Cheng, S.-Y., Shires, M. K., & Drake, B. (2023). Child fatality in families with prior CPS history: Do those with and without intimate partner violence differ? Journal of Family Violence, 38(4), 687–702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-022-00383-9

*Jordan, J. T., & McNiel, D. E. (2021). Homicide-suicide in the United States: Moving toward an empirically derived typology. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 82(2), 28068. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.20m13528

Kafka, J. M., Moracco, K. E., Pence, B. W., Trangenstein, P. J., Fliss, M. D., & Reyes, H. L. M. (2023). Intimate partner violence and suicide mortality: A Cross-sectional study using machine learning and natural language processing of suicide data from 43 states. Injury Prevention. https://doi.org/10.1136/ip-2022-044662

Karlsson, L. C., Antfolk, J., Putkonen, H., Amon, S., da Silva Guerreiro, J., de Vogel, V., Flynn, S., & Weizmann-Henelius, G. (2021). Familicide: A systematic literature review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 22(1), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838018821955

*Kauppi, A., Kumpulainen, K., Karkola, K., Vanamo, T., & Merikanto, J. (2010). Maternal and paternal filicides: A retrospective review of filicides in Finland. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 38(2), 229–238.

Kieselbach, B., Kimber, M., MacMillan, H. L., & Perneger, T. (2022). Prevalence of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence in low-income and lower-middle-income countries: A systematic review. British Medical Journal Open, 12(4), e051140. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051140

Kim, B., & Merlo, A. V. (2023). Domestic homicide: A synthesis of systematic review evidence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(2), 776–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211043812

*Kristoffersen, S., Lilleng, P. K., Mæhle, B. O., & Morild, I. (2014). Homicides in Western Norway, 1985–2009, time trends, age and gender differences. Forensic Science International, 238, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2014.02.013

*Lecomte, D., & Fornes, P. (1998). Homicide followed by suicide: Paris and its suburbs, 1991–1996. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 43(4), 760–764. https://doi.org/10.1520/JFS14303J

Lewis, N. V., Feder, G. S., Howarth, E., Szilassy, E., McTavish, J. R., MacMillan, H. L., & Wathen, N. (2018). Identification and initial response to children’s exposure to intimate partner violence: A qualitative synthesis of the perspectives of children, mothers and professionals. British Medical Journal Open, 8(4), e019761. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019761

*Liem, M. c. a., & Koenraadt, F. (2007). Homicide-suicide in the Netherlands: A study of newspaper reports, 1992 - 2005. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology, 18(4), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789940701491370

*Logan-Greene, P., Nurius, P. S., Hooven, C., & Thompson, E. A. (2013). The sustained impact of adolescent violence histories on early adulthood outcomes. Victims & Offenders, 8(2), 231–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2012.755139

*Lyons, V. H., Adhia, A., Moe, C. A., Kernic, M. A., Schiller, M., Bowen, A., Rivara, F. P., & Rowhani-Rahbar, A. (2021a). Risk factors for child death during an intimate partner homicide: A case-control study. Child Maltreatment, 26(4), 356–362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559520983901

*Lyons, V. H., Adhia, A., Moe, C., Kernic, M. A., Rowhani-Rahbar, A., & Rivara, F. P. (2021b). Firearms and protective orders in intimate partner homicides. Journal of Family Violence, 36(5), 587–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00165-1

Mailloux, S. (2014). Fatal families: Why children are killed in familicide occurrences. Journal of Family Violence, 29, 921–926. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-014-9643-0

*Mathews, S., Abrahams, N., Martin, L. J., Lombard, C., & Jewkes, R. (2019). Homicide pattern among adolescents: A national epidemiological study of child homicide in South Africa. PLOS ONE, 14(8), e0221415. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221415

*McLachlan, F., & Harris, B. (2022). Intimate risks: Examining online and offline abuse, homicide flags, and femicide. Victims & Offenders, 17(5), 623–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2022.2036658

*Messing, J. T., & Heeren, J. W. (2004). Another side of multiple murder: Women killers in the domestic context. Homicide Studies, 8(2), 123–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088767903262446

*Meyer, E., & Post, L. (2013). Collateral intimate partner homicide. SAGE Open, 3(2), 2158244013484235. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244013484235

Michaels, N. L., & Letson, M. M. (2021). Child maltreatment fatalities among children and adolescents 5–17 years old. Child Abuse & Neglect, 117, 105032. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105032

*Moen, M., & Bezuidenhout, C. (2023). Killing your children to hurt your partner: A South African perspective on the motivations for revenge filicide. Journal of Investigative Psychology and Offender Profiling, 20(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/jip.1603

*Morton, E., Runyan, C. W., Moracco, K. E., & Butts, J. (1998). Partner homicide-suicide involving female homicide victims: a population-based study in North Carolina, 1988-1992. Violence and Victims, 13(2), 91-106. https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.13.2.91

*Moskowitz, H., Laraque, D., Doucette, J. T., & Shelov, E. (2005). Relationships of US youth homicide victims and their offenders, 1976-1999. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 159(4), 356–361. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.159.4.356

Moylan, C. A., Herrenkohl, T. I., Sousa, C., Tajima, E. A., Herrenkohl, R. C., & Russo, M. J. (2010). The effects of child abuse and exposure to domestic violence on adolescent internalizing and externalizing behavior problems. Journal of Family Violence, 25(1), 53–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-009-9269-9

Mueller, I., & Tronick, E. (2020). The long shadow of violence: The impact of exposure to intimate partner violence in infancy and early childhood. International Journal of Applied Psychoanalytic Studies, 17(3), 232–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/aps.1668

*Myers, W. C., Lee, E., Montplaisir, R., Lazarou, E., Safarik, M., Chan, H. C. (Oliver), & Beauregard, E. (2021). Revenge filicide: An international perspective through 62 cases. Behavioral Sciences & the Law, 39(2), 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2505

Nielssen, O. B., Large, M. M., Westmore, B. D., & Lackersteen, S. M. (2009). Child homicide in New South Wales from 1991 to 2005. Medical Journal of Australia, 190(1), 7–11. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02252.x

Niolon, P. H., Kearns, M., Dills, J., Rambo, K., Irving, S., Armstead, T., & Gilbert, L. (2017). Preventing intimate partner violence across the lifespan: A technical package of programs, policies, and practices. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/ipv-technicalpackages.pdf

*Nordlund, J., & Temrin, H. (2007). Do characteristics of parental child homicide in Sweden fit evolutionary predictions? Ethology, 113(11), 1029–1037. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1439-0310.2007.01412.x

*Olszowy, L., Jaffe, P. G., Campbell, M., & Hamilton, L. H. A. (2013). Effectiveness of risk assessment tools in differentiating child homicides from other domestic homicide cases. Journal of Child Custody, 10(2), 185–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/15379418.2013.796267

*Olszowy, L., Jaffe, P., & Saxton, M. (2021). Examining the role of child protection services in domestic violence cases: Lessons learned from tragedies. Journal of Family Violence, 36(8), 927–939. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-020-00171-3

*Panczak, R., Zwahlen, M., Spoerri, A., Tal, K., Killias, M., Egger, M., & Cohort, for the S. N. (2013). Incidence and risk factors of homicide–suicide in Swiss households: National cohort study. PLOS ONE, 8(1), e53714. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0053714

Peitzmeier, S. M., Malik, M., Kattari, S. K., Marrow, E., Stephenson, R., Agénor, M., & Reisner, S. L. (2020). Intimate partner violence in transgender populations: Systematic review and meta-analysis of prevalence and correlates. American Journal of Public Health, 110(9), e1–e14. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305774

*Putkonen, H., Amon, S., Eronen, M., Klier, C. M., Almiron, M. P., Cederwall, J. Y., & Weizmann-Henelius, G. (2011). Gender differences in filicide offense characteristics—A comprehensive register-based study of child murder in two European countries. Child Abuse & Neglect, 35(5), 319–328. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.01.007

Reyes, H. L. M., Graham, L. M., Chen, M. S., Baron, D., Gibbs, A., Groves, A. K., Kajula, L., Bowler, S., & Maman, S. (2021). Adolescent dating violence prevention programmes: A global systematic review of evaluation studies. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 5(3), 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30276-5

*Saleva, O., Putkonen, H., Kiviruusu, O., & Lönnqvist, J. (2007). Homicide–suicide—An event hard to prevent and separate from homicide or suicide. Forensic Science International, 166(2), 204–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2006.05.032

*Shiferaw, K., Burkhardt, S., Lardi, C., Mangin, P., & Harpe, R. L. (2010). A half century retrospective study of homicide–suicide in Geneva – Switzerland: 1956–2005. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine, 17(2), 62–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jflm.2009.09.003

*Sidebotham, P., & Retzer, A. (2019). Maternal filicide in a cohort of English Serious Case Reviews. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 22(1), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-018-0820-7

Sijtsema, J. J., Stolz, E. A., & Bogaerts, S. (2020). Unique risk factors of the co-occurrence between child maltreatment and intimate partner violence perpetration. European Psychologist. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000396

*Sillito, C. L., & Salari, S. (2011). Child outcomes and risk factors in U.S. homicide-suicide cases 1999–2004. Journal of Family Violence, 26(4), 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-011-9364-6

Skafida, V., & Devaney, J. (2023). Risk and protective factors for children’s psychopathology in the context of domestic violence–A study using nationally representative longitudinal survey data. Child Abuse & Neglect, 135, 105991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105991

Skafida, V., Morrison, F., & Devaney, J. (2022). Intimate partner violence and child maltreatment in Scotland-Insights from nationally representative longitudinal survey data. Child Abuse & Neglect, 132, 105784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105784

Smith, S. G., Fowler, K. A., & Niolon, P. H. (2014). Intimate partner homicide and corollary victims in 16 states: National Violent Death Reporting System, 2003–2009. American Journal of Public Health, 104(3), 461–466. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301582

Smucker, S., Kerber, R. E., & Cook, P. J. (2018). Suicide and additional homicides associated with intimate partner homicide: North Carolina 2004–2013. Journal of Urban Health, 95(3), 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-018-0252-8

Sokoloff, N. J., & Dupont, I. (2005). Domestic violence at the intersections of race, class, and gender: Challenges and contributions to understanding violence against marginalized women in diverse communities. Violence Against Women, 11(1), 38–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801204271476

*Tosini, D. (2017). Familicide in Italy: An exploratory study of cases involving male perpetrators (1992–2015). Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 088626051771443. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517714436

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’brien, K., Colquhoun, H., Kastner, M., Levac, D., Ng, C., Sharpe, J. P., & Wilson, K. (2016). A scoping review on the conduct and reporting of scoping reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 16, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-016-0116-4

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D., Horsley, T., & Weeks, L. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Truong, M., Yeganeh, L., Cartwright, A., Ward, E., Ibrahim, J., Cuschieri, D., Dawson, M., & Bugeja, L. (2023). Domestic/family homicide: A systematic review of empirical evidence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(3), 1908–1928. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380221082084

Turner, W., Hester, M., Broad, J., Szilassy, E., Feder, G., Drinkwater, J., Firth, A., & Stanley, N. (2017). Interventions to improve the response of professionals to children exposed to domestic violence and abuse: A systematic review. Child Abuse Review, 26(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2385

Weir, H., Kaukinen, C., & Cameron, A. (2021). Diverse long-term effects of childhood exposure to intimate partner violence: Development of externalizing behaviors in males and females. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(21–22), NP12411–NP12435. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519888528

*Wilson, M., Daly, M., & Daniele, A. (1995). Familicide: The killing of spouse and children. Aggressive Behavior, 21(4), 275–291. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(1995)21:4<275::AID-AB2480210404>3.0.CO;2-S

Acknowledgements

We want to thank Dr. Rebecca Macy for her assistance with conceptualizing this scoping review and determining which articles from initial searches met inclusion criteria. We also thank Ms. Ametisse Gover-Chamlou who supported early search and article screening processes as a Graduate Research Assistant at the University of Maryland School of Social Work in Baltimore, MD.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Graham, L.M., Jun, HJ., Kim, J. et al. Characteristics of Child Fatalities that Occur in the Context of Current or Past Intimate Partner Violence: a Scoping Review. J Fam Viol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-024-00713-z

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-024-00713-z