Abstract

Purpose

This review aimed to investigate and describe the current research that has reported on family violence and food insecurity and to explore any links. Research is beginning to explore the relationship between food insecurity and family violence, as such, this is a good time to review the current body of literature to identify existing gaps.

Methods

This research employed a narrative systematic review allowing for a broad search while maintaining methodological rigour. Key word searches were performed in 6 electronic databases in January 2023. Two overarching concepts were used: “family violence” and “food security”. The findings were synthesised into a narrative review, reporting on specific population groups separately.

Results

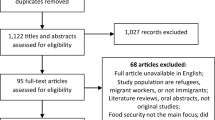

The search generated 1724 articles, of which 868 were duplicates. The titles and abstracts of 856 articles were screened; 765 articles were excluded because they did not investigate the experience of food insecurity and family violence. The full text of 91 articles was reviewed, with 32 included in this review. Most were from the USA, and most employed qualitative or mixed methods. Studies explored food insecurity and family violence in women, men and women, children, people who are HIV positive, and the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and food insecurity.

Conclusions

Food insecurity and family violence are significant societal problems, with evidence that both have increased in prevalence and severity due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This review provides initial evidence for a bi-directional relationship between food insecurity and family violence in high income countries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life (FAO, 2013). Food insecurity describes a situation when a household or individual does not have access to food because of a lack of financial or other resources (Gundersen & Ziliak, 2015). Despite increased access to resources and economic advantages, approximately 10% of people living in high‐income countries experience food insecurity, with factors relating to food insecurity varying by level of development and Gross Domestic Product per capita (Smith et al., 2017). Hunger is the most serious outcome of food insecurity and typically refers to insufficient consumption of food or energy required for daily living and activity (FAO, 2021). Food insecurity is a social determinant of health and can lead to and result from a range of household stressors. Researchers have begun to explore the relationship between food insecurity and family violence, highlighting the possibility of a bidirectional relationship, where family violence both leads to and results from food insecurity (Laurenzi et al., 2020). To date there is no clear consensus on this relationship. This narrative review aims to investigate and describe the current research that has reported on family violence and food insecurity and to explore any links.

Background

Estimates suggest that globally, over 820 million people experienced food insecurity in 2021, an increase over previous years (FAO et al., 2022). Experiences of food insecurity can range from mild to severe; from compromising on quality and variety of food, through to eating reduced portions or skipping meals, to not consuming any food for a day or longer (McKay et al., 2023).

Household food insecurity is linked with a range of negative health outcomes (Murthy, 2016), and chronic health conditions for both adults and children (Goldstein et al., 2017; Gundersen & Ziliak, 2015). Food insecurity during pregnancy is of particular concern with food insecure pregnant women found to be more likely to have excessive gestational weight gain (Crandall et al., 2020; Demétrio et al., 2020; Nunnery et al., 2018), develop gestational diabetes and enter preterm labour (Laraia et al., 2010), and experience mental health concerns (Augusto et al., 2020; Maynard et al., 2018). The children born of women who are food insecure are more likely to experience birth defects, cognitive problems, and anxiety, and when compared to children in food secure households are two to three times more likely to develop anaemia, two times more likely to be in fair to poor health, and are more likely to have asthma (Gundersen & Ziliak, 2015). Additionally, children who grow up with the stress of food insecurity are more likely to develop chronic health conditions as adults, including obstructive pulmonary disease, depression, autoimmune diseases, and cancers (Garner et al., 2012), and are more likely to be obese (Dubois et al., 2016). Among adults, food insecurity is associated with increased risk of some chronic conditions including type 2 diabetes (Abdurahman et al., 2019; Thomas et al., 2021), and cardiovascular disease (Holben & Marshall, 2017; Liu & Eicher-Miller, 2021), and is strongly linked with overweight and obesity (Burns, 2004; Dinour et al., 2007; Moradi et al., 2019).

Households that experience financial, or cost of living, pressures can also experience food insecurity. These pressures have increased over recent years as major global disruptions such as the Great Recession (2007 to 2009), the Coronavirus pandemic (2020 to 2023), and the period of high inflation during 2022 and 2023, have led to increased inequality and to the increased risk of household food insecurity (Idzerda et al., 2022; Waxman et al., 2022). To manage their household food insecurity, households often change their food preferences and behaviours. As income is reduced, so too is the ability to afford nutrient-rich foods, forcing these households to substitute highly processed, energy dense foods (Drewnowski, 2009). It has also been suggested that the stress surrounding food scarcity activates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis pathway in the brain, which in turn activates the hedonic, or reward, brain pathway (Dallman et al., 2003). Ongoing consumption of a lower quality diet, particularly one that includes ultra-processed foods, results in further risk of developing chronic health conditions including obesity, type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and some cancers (Hall et al., 2019; Jayedi et al., 2020).

Family violence similarly has long and short-term implications on households and individuals. Family violence is the physical, psychological, sexual or verbal harm inflicted upon relations within a household, most commonly from male partners to female partners (partner here referring to an intimate relationship, for example, a boyfriend, husband, or de facto partner) (Kelsey Hegarty et al., 2000). Family violence is a complex public health issue that affects individuals from a diverse range of economic, social, geographic, and racial backgrounds (Kelsey Hegarty et al., 2000). In high income countries, 22% of women aged 15–49 are estimated to experience some form of family violence (WHO, 2021). When attempting to leave an abusive relationship many women report that they find it difficult to leave their abusive partner, due to a wide range of factors (Yamawaki et al., 2012), including a lack of financial resources, lack of support from police or from other support services, lack of alternative housing, negative self-perception, and difficulties relating to legal issues surrounding the custody of children (Anderson et al., 2003; Martin et al., 2000). Women who have experienced family violence are more likely to have ongoing concerns for their safety, post-traumatic stress disorder, increased experiences of fear, and a greater degree of absenteeism from their work (Black et al., 2011). Children who experience violence in the home are more likely to experience anxiety, depression, aggressive behaviour, and emotional dysregulation (Zarling et al., 2013). Those who experience family violence also experience significant stigma, which prevents them from accessing social support and services (Murray et al., 2016).

Research exploring the links between food insecurity and family violence is in its infancy. There is, however, evidence that demonstrates the associations between family violence and mental health (Humphreys & Thiara, 2003), and between food insecurity and mental health (Tarasuk et al., 2018; Weaver & Hadley, 2009). Proposed reasons for the link between food insecurity and family violence are that families who are vulnerable to food insecurity may be experiencing increased household stress and poor mental health, which may lead to or result from family violence.

With an increasing number of people experiencing household food insecurity as cost-of-living pressures impact household budgets, there is a risk that the incidence of family violence will also increase, compounding the short- and long-term impacts of both experiences. Understanding the relationship between these experiences is important when designing programs and responses that seek to assist families who are experiencing both food insecurity and family violence. This systematic narrative review seeks to summarise current research and highlight any examined links between family violence and food insecurity.

Method

This research employed a systematic narrative review. As outlined by Ferrari, (2015), narrative reviews tend to have broad research questions and allow for the greater scope in inclusion criteria. A narrative review was selected for this study as the links between food insecurity and family violence are only beginning to be explored, so this approach allowed for a broader scope of searching, while maintaining methodological rigour.

Eligibility Criteria

Eligible publications were those that examined both food insecurity and family violence. All study designs were included, and no limitations were placed, on study population, or the type of the study.

Studies were excluded if they did not examine both food insecurity and family violence, or if they were not from a high-income country (as defined by the Human Development Index). Non-English language papers were excluded. Non-empirical studies, such as editorials, theses, and reviews were excluded. Conference abstracts were excluded.

Search Strategy

Consistent with the method for narrative reviews proposed by Ferrari, (2015), where search terms are purposely general, the search included two overarching concepts to identify relevant articles: “family violence” and “food security”, Table 1 shows the key search terms used for each concept. Literature searches of key words were performed in 6 electronic databases, Medline, Embase, CINAHL, Global Health, PsycARTICLES, SocINDEX, Academic Search Complete. The search was completed in January 2023.

Following the literature search, all identified citations were uploaded into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, 2022), a web-based software platform designed to simplify and expedite the research review process. Duplicate search results were then removed. Titles and abstracts were independently screened by two authors. Full texts were screened independently by both authors. Disagreement between authors regarding study inclusion were resolved through discussion to meet consensus.

Family violence can be described in the literature in a variety of ways, including domestic violence and intimate partner violence. For the purposes of this review, all such descriptors of family violence were included. Similarly, studies that referred to both food insecurity or food security were included. Survivors of family violence could include men, women, and children. A study could examine those who previously experienced family violence, or who were currently experiencing it. Included studies are those that examined the relationship between family violence and food insecurity, studies were excluded if they reported independently on food insecurity and family violence. Studies that were conducted or related to low- or middle-income countries, as defined by the Human Development Index were excluded.

Data Extraction

Data were extracted from included studies. Using a data extraction template, the following data were extracted: Author, year, journaltitle, country, method, population group (women, men, both men and women, children), and the main findings, if family violence was found to increases food insecurity, and if food insecurity increases family violence. Findings were narratively synthesised and reported according to specific population groups. Two individual health outcomes were commonly reported; HIV infection and the COVID-19 pandemic, as such, these are reported separately.

In reporting the findings from these studies, we have used the language of the original authors. This means that in the following results section, we use the terms family violence, domestic violence, and intimate partner violence as they have been used in the original studies. When not reporting directly on findings, we use the term family violence as an umbrella term for all these forms of violence.

Results

The search generated 1724 articles, of which 868 were duplicates. The titles and abstracts of 856 articles were screened; 765 articles were excluded because they did not investigate the experience of food insecurity and family violence, leaving 91 articles for full text review. The full text of 91 articles was reviewed; 58 articles were excluded as they did not meet the inclusion criteria, see Fig. 1. The remaining 32 studies have been included in this review, of which 27 were from the United States of America (USA), three from Canada, and one each from the United Kingdom and New Zealand. Ten studies employed a cross sectional methodology, twelve employed a longitudinal methodology, six used a qualitative methodology, two were prospective cohort studies, and one used a mixed method approach. Time of publication ranged from 2006 to 2022, with 27 published since 2015. See supplementary table 1 for description of the studies included.

Family Violence, Food Insecurity, and Women

Twelve studies reported on the experiences of family violence and food insecurity among a female population (Barreto et al., 2019; Brandhorst & Clark, 2022; Chilton & Booth, 2007; Chilton et al., 2014, 2017; Daundasekara et al., 2022; Hernandez et al., 2014; Hunt et al., 2019; Laraia et al., 2022; Melchior et al., 2009; Power, 2006; Ricks et al., 2016), nine of these studies were based in the USA, two in Canada, and one in the UK. Five studies that focused on a female population specifically were longitudinal, four were qualitative, two were cross sectional, and one was a case study. When considering the direction of the relationship between food insecurity and family violence all studies but one reported that experiencing family violence or abuse was associated with an increased risk of experiencing food insecurity. One study (Hunt et al., 2019), did not report on the direction of the relationship.

Studies sought to explore the relationship with severity of food insecurity and family violence. In a large, repeated cross sectional study, Ricks et al., (2016) used six years of data from the California Women’s Health Survey to assess the relationship between different levels of food insecurity and the experience of intimate partner violence. Findings indicate that 22% of participants were food insecure, with increased severity of food insecurity related to increased severity of intimate partner violence. Similarly, Hunt et al., (2019) found that women in Chicago who were food insecure were more likely to report intimate family violence compared with those who were food secure, though this relationship was not significant, while women who were food insecure were statistically more likely to access emergency and community food assistance (food stamps) than those who were food secure (65.2% vs 30.1%, respectively). Use of food stamps by women who were experiencing intimate partner violence was also reported in the study by Brandhorst & Clark, (2022) in an examination of the experience of intimate partner violence on food security, and the relationship between food insecurity and wellbeing. This study found food insecurity highest among women who had experienced domestic violence in the previous 3 months, who were using emergency and community food assistance, or who had children (Brandhorst & Clark, 2022).

Five studies reported on women who were pregnant or who had children in the home and all reported an association between food insecurity, family violence, and maternal depressive symptoms (Chilton et al., 2014; Daundasekara et al., 2022; Hernandez et al., 2014; Laraia et al., 2022; Melchior et al., 2009). In a longitudinal study of women from the UK, Melchior et al., (2009) found that food insecurity was associated with maternal depression (OR: 2.82 [95% CI: 1.62–4.93]) and domestic violence (OR: 2.36 [95% CI: 1.18–4.73]) when controlled for income. Similarly, in longitudinal work with women from the USA, Hernandez et al., (2014) found that food insecurity was associated with domestic violence (OR: 1.22 [95% CI: 1.01–1.49]) and significantly associated with depression (OR: 2.03 [95% CI: 1.45–2.84] p < 0.001). Also in longitudinal work from the USA Daundasekara et al., (2022) found that mothers had increased odds of major depression when experiencing food insecurity (OR = 1.69, p < 0.001), domestic violence (OR = 1.54, p < 0.001), or both concurrently (OR = 1.88, p = 0.004). Laraia et al., (2022) found that women reporting very low food security had a 165% (95% CI: 1.86–3.79) greater risk of experiencing domestic violence compared to those not experiencing food insecurity, while having a husband or partner who were unemployed, who were experiencing depressive symptoms, and experiencing domestic violence were all significantly associated with food insecurity. Finally, in a mixed-method study Chilton et al., (2014) employing a survey, photo voice, and semi structured interviews to explore violence and food insecurity in households headed by women. This study found that a higher proportion of women who reported very low food security also reported experiencing depressive symptoms, when compared to the food secure groups (71% vs 17%, respectively), with women who reported very low food security also reported currently experiencing violence from an intimate partner, compared with women who were food secure (88% vs 75%, respectively). Experiences of violence were common in all women in this cohort, but the most severe experiences (with a “life changing impact” such as rape, or murder or suicide of someone close to the participant) were proportionally greater in the very low food security cohort compared with food secure (59% vs 33%), while those experiencing very low food security were also more likely to describe themselves as a perpetrator of domestic violence, compared with the food secure women (59% vs 17%, respectively). In qualitative work with women, of which half had children in the home, Chilton & Booth, (2007) found that family violence and food insecurity was associated with depression and worry about running out of food and not being able to get more.

Exploring the impact of intergenerational hardship on food insecurity and violence Chilton et al., (2017), found household food insecurity was linked with exposure to violence and adversity across the life course, with some indications that it can transfer across generations. This qualitative study with mothers showed how hunger, violence, and adversity were interrelated, and inseparable.

In work exploring the experiences of cis and trans women sex workers through a longitudinal study Barreto et al., (2019) found that almost two thirds of sex workers were food insecure, increasing to almost three-quarters at the end of the five year study period, while almost all of the sex workers living with HIV were food insecure at some point during the study, compared to 69.3% of sex workers who were not living with HIV. This study reported an almost fivefold increased odds for food insecurity among those who experienced lifetime violence and 50% increased odds among those experiencing recent physical and/or sexual violence.

Power, (2006) explored the experiences of one woman who was experiencing financial, sexual, and physical abuse from her husband. The financial abuse was found to compound her experiences of food insecurity, as it affected her ability to provide enough food for herself and her children. While the women engaged in traditional coping strategies (using coupons, altering recipes, comparison shopping), she was unable to meet the exacting standards of her husband’s food requests, leading to further abuse.

Family Violence, Food Insecurity, and Both Men and Women

Six studies reported on the relationship between family violence and food insecurity among both men and women. All were based in the USA, five employed a cross sectional methodology (Adhia et al., 2020; Breiding et al., 2017; Caetano et al., 2019; Cunradi et al., 2020; Fedina, Ashwell, et al., 2022) and one study employed a longitudinal design (Schwab-Reese et al., 2016). Two used a study population who had attended an emergency department in the same northern California hospital (Caetano et al., 2019; Cunradi et al., 2020).

All studies reported an association between experiences of food insecurity, and either being a perpetrator or a victim of family violence. In a large cross sectional study (n = 1620) Adhia et al., (2020) sought to determine if life events, such as loss of food security or support, could change family violence perpetration. This study separated the sample into those who had never perpetrated violence, ‘persisters’ who had a long history of engaging in family violence, ‘desisters’ who stopped perpetrating family violence, and ‘late onsetters’ those who began perpetrating family violence after the age of 31. Loss of food security was associated with 10.3 times higher odds being a late-onsetter of domestic violence (OR = 10.3, 95% CI = 1.9, 55.4) compared with those who perpetrated family violence also as a young adult, with the authors suggesting that life events such as food insecurity can contribute to the incidence of family violence. A cross sectional study by Breiding et al., (2017) found that women and men who experienced food insecurity were more likely to experience forms of intimate partner violence than those who were food secure. This study combined food insecurity with housing insecurity to form the variable ‘economic insecurity’. Women who reported high levels of economic insecurity were more likely to report physical violence (AOR = 4.5, 95% CI = [2.7–7.5]), psychological aggression (AOR = 3.6, 95% CI = 2.7–4.7]) and control of reproductive or sexual health (AOR = 5.9, 95% CI = [2.3–15.1]), than those who were food secure, in the previous 12 months. Similar results were observed for men, with men who reported high levels of economic insecurity more likely to experiences all forms of intimate partner violence in the previous 12 months than men who were food secure.

Cunradi et al., (2020), identified a positive association between experiences of food insecurity, and both intimate partner violence victimisation and perpetration among women in a large (n = 1037) cross sectional study. Intimate partner violence victimisation and perpetration frequencies were greater for women than men, as was the frequency of ‘severe’ intimate partner violence (which included choking, slamming against walls, and use of a weapon like a knife or a gun). Women who reported experiencing food insecurity also experienced greater intimate partner violence frequency (b = 15.763; p < 0.01) when compared with women who were food secure. There were no significant findings for food insecurity and family violence in men. Caetano et al., (2019) examined the same population (n = 1037), finding that respondents who were food insecure ‘sometimes’ or ‘often’ were 1.76 (95% CI = 1.19–2.61) and 1.95 (95% CI = 1.14–3.35) times more likely, respectively, to report that they had experienced intimate partner violence compared to those who did not experience food insecurity.

A large longitudinal study by Schwab-Reese et al., (2016) examined associations between different types of intimate partner violence (minor, severe, or causing injury) and different financial stressors, including food insecurity. More women than men reported food insecurity (14% vs 9.9% respectively, p < 0.001). More women than men also reported perpetrating minor (11.4% vs 6.7%, p < 0.001) or severe (8.8% vs 3.4%, p < 0.001) violence against an intimate partner, but men perpetrated domestic violence causing injury more commonly (32% vs 21%, p = 0.003). After adjusting for confounders, food insecurity remained the only identified financial stressor that was significantly associated with all three levels of perpetrating intimate partner violence. This contrasts a recent study by Fedina, Ashwell, et al. (2022), who used data from the USA National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey to examine the experiences of men and women with victimisation from domestic violence. Findings indicate that more men than women experienced intimate partner violence, described in this study as including physical, psychological, controlling, sexual, or isolating abuse (22.9% vs 19%, respectively), while more women reported experiencing food insecurity (28.3% vs 21.6%, respectively). For women, experiencing intimate partner violence was significantly associated with higher odds of also experiencing food insecurity (OR = 2.16, 95% CI = [1.75–2.66]), and this association was greater in men (OR = 2.40, 95% CI = [1.88–3.06]).

Family Violence, Food Insecurity and Children

Six studies focused on the relationship between family violence and abuse of children and the relationship with food insecurity. Five studies were based in the USA (Chilton et al., 2015; Helton et al., 2019; Jackson et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2022; Vaughn et al., 2016), one from New Zealand (Gulliver et al., 2018), three studies employed a longitudinal design, two studies employed a cross sectional design, and one each employed a qualitative design.

In a longitudinal investigation of risk factors that can explain changes in adolescent exposure to family violence from New Zealand, Gulliver et al., (2018) suggested that over time, food insecurity was associated with witnessing emotional or physical violence at home. This work suggests that a decrease in witnessing family violence over time can lead to an improvement in food security.

The remaining five studies based in the USA found that mistreatment, abuse, and violence against children was associated with households that were food insecure. Jackson et al., (2018) found a significant relationship between household food insecurity across each time points and violence in the home. These results held even after cofounders were taken into consideration. Kim et al., (2022) used a measure of ‘child maltreatment reports’, records of reports made to local child protection services, and include neglect, physical violence, and sexual violence across seven years. An average 47.7 per 1000 children were the subject of a child maltreatment report, with neglect the most common reason followed by physical violence, with each year, on average, 12.3% of households experiencing food insecurity. The within-effect and between-effect of food insecurity were both significantly associated with an increase in child maltreatment report rates in all models, with a one percentage increase in within-effect of food insecurity resulting in an increase of child maltreatment report rates (with controls) of 1.28 (coefficient = 1.28; 95% CI: 2.76, 4.33) There was a strong bivariate association between the rate of food insecurity, and the rate of child maltreatment reports (r = 0.6, p < 0.0001). Helton et al., (2019) used ten questions relating to physical or psychological violence perpetrated by parents towards their children (‘aggression scores’) as part of a larger survey relating to child health, behaviour, and parenting strategies. Across the waves of the study the mean prevalence of persistent food insecurity was 29% of households. An association between the aggression scores of parents and food insecurity was identified. Across all models, the presence of food insecurity resulted in increased rates of psychological, physical, and total aggression. Independent of the type of abuse, aggression scores increased by 0.077–0.136 standard deviations when the household was also experiencing food insecurity. Chilton et al., (2015) explored if adverse childhood experiences are associated with food insecurity through an exploring of caregivers’ perceptions of the impact of their childhood adversity on educational attainment, employment, and mental health. Adverse childhood experiences and severity were significantly associated with reports of very low food security (Fisher’s exact p = 0·021). Mothers reporting childhood emotional and physical abuse were more likely to report very low food security (Fisher’s exact p = 0·032). Qualitatively, participants described the impact of childhood adverse experiences with emotional and physical abuse/neglect, and household substance abuse, on their emotional health, school performance and ability to maintain employment, these experiences negatively affected their ability to protect their children from food insecurity. Vaughn et al., (2016) explored the association of food insecurity and hunger during childhood and with an array of developmental problems including impulse control problems and violence. This longitudinal study found that participants who experienced frequent hunger during childhood had significantly greater impulsivity, worse self-control, and greater involvement in several forms of interpersonal violence.

Family Violence, Food Insecurity and Human Immunodeficiency Viruses (HIV)

Five studies reported on the association of food insecurity and family violence, among women who were living with HIV or at risk of HIV infection (Conroy et al., 2019; Leddy et al., 2021; Lim et al., 2019; Montgomery et al., 2015; Ohtsuka et al., 2022). Four studies were from the United States, and one from Canada. All five studies focused on women.

All studies found a significant relationship between family violence and food insecurity. Montgomery et al., (2015) found that all kinds of reported family violence were associated with risky HIV behaviours, including unprotected sex, and sex work. Sexual or physical domestic violence was found to be associated with disclosure of the participant’s HIV status without their consent (Ohtsuka et al., 2022). The reported prevalence of violence was high among the women surveyed, with 79% of women reporting physical or sexual domestic abuse in their lifetime (Ohtsuka et al., 2022), 43% reporting childhood sexual violence, and 14% reporting physical intimate partner violence (Lim et al., 2019). Food insecurity among participants was reported to be 46.3% (Montgomery et al., 2015), 77.3% (Ohtsuka et al., 2022), and 26% described going without food at night ‘most days of the week’ (Lim et al., 2019). Lim et al., (2019) reported that those with ‘severe’ food insecurity were more likely to be engaging in unsafe HIV behaviours, such as using drugs intravenously (p = 0.025). After adjusting for confounders, Conroy et al., (2019) found the odds of experiencing sexual or physical violence were 3.12 times greater for women with ‘very low’ food security, compared to those who were food secure (95% CI: 1.88, 5.19). Similarly, Lim et al., (2019) found that women whose food insecurity was ‘severe’ were more likely to experience physical intimate partner violence (p = 0.004) than women who were food secure. Using multivariate GEE analysis Ohtsuka et al., (2022) found that food insecurity was associated with an increased odds of experiencing physical or sexual violence in the previous six months (AOR: 1.57, 95% CI [1.13, 2.17]). Women who reported experiencing multiple kinds of violence in the previous six months were almost twice as likely to also report food insecurity (OR: 1.93, CI [1.41, 2.65]) (Montgomery et al., 2015).

In a qualitative study Leddy et al., (2021), examined the relationship between food insecurity, domestic violence, and HIV related behaviours. All the women interviewed (n = 24) experienced very low food security, and experienced disrupted eating patterns because they lacked food or the resources to access it. The women commonly experienced physical partner violence, emotional partner violence, or concurrent physical and emotional violence, with the experience of simultaneous violence and food insecurity reinforcing poor mental health and substance abuse. Lack of material resources meant that women were reliant on abusive partners for food or money, and they were often unable to leave these situations as they could not support themselves. Additionally, the experience of domestic violence was often heightened by food insecurity, with abusive partners withholding food or consuming an unequal share of the household’s food.

Family Violence, Food Insecurity and the COVID-19 Pandemic

Three studies reported on the potential effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on food insecurity and family violence (Clark & Jordan, 2022; Fedina et al., 2022a, b; Krause et al., 2022). All three studies were based in the USA.

All studies reported an increase in food insecurity due to the pandemic but did not find an increase in family violence. Fedina et al., (2022a, b) explored the imapct of the pandemic and stay at home orders on women and transgender adults to assess if food insecurity and family violence had increased, finding that violence decreased during this period (from 16.6% to 15.5% of the sample), while around one quarter of participants reported an increase in food insecurity since the beginning of the pandemic. Significant associations between food insecurity and experiences of intimate partner violence were not identified, despite finding significant associations between intimate partner violence and housing insecurity (AOR = 3.06, p < 0.001), and health care insecurity (AOR = 2.95, p < 0.001).

Clark & Jordan, (2022) reported increased food insecurity as a result of the pandemic among women who had experienced abuse in their lifetime. This increase in food insecurity was attributed not only to changes in financial situation due to unemployment or reduced work hours due to stay at home orders, but also due to difficulty in getting to supermarkets and food stores (Clark & Jordan, 2022).

Krause et al., (2022) explored the prevalence sexual and physical dating violence victimization among adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic and to investigate whether experiences of disruption and adversity put adolescents at greater risk of interpersonal violence. Both male and female adolescents experienced sexual and physical dating violence. Hunger was associated with sexual and physical dating violence among female students and homelessness was associated with physical dating violence among male students. Abuse by a parent, hunger, and homelessness created precarity that may have increased the likelihood that adolescents would be exposed to risky peer or dating relationships.

Discussion

This is the first narrative review to synthesise the literature exploring the associations between family violence and food insecurity in high income countries. This synthesis of 32 studies published between 2006 and 2022 highlight a relationship between food insecurity and family violence across multiple settings, including family violence against children, and adults who are both perpetrators and victims of intimate partner violence, and in populations with health conditions such as HIV, and the potential effects of the Covid-19 pandemic.

The cross-sectional and qualitative nature of many of the studies included make it difficult to establish the direction of the relationship between family violence and food insecurity, or if other intervening variables might explain the association, however, there is emerging evidence for a bi-directional relationship. For example, women who were being abused, or who are economically trapped, might be denied access to financial resources or employment opportunities by their abuser, restricting their ability to purchase food, leading to food insecurity (Goodman et al., 2009; Montgomery et al., 2015). Experiencing economic insecurity that affects a household’s ability to buy adequate food could lead to stress and increase relationship conflict, making family violence and conflict in a relationship more likely (Capaldi et al., 2012). It may also be that women who leave abusive situations are at increased risk of food insecurity as they often experience financial insecurity because of the drastic socioeconomic changes that may result after leaving a financially supportive abuser (Laurenzi et al., 2020).

Previous studies investigating the relationship between family violence and food insecurity in low- and middle-income countries have found similar results as our review. A 2016 study of women from Cote d’Ivoire found that women who reported experiencing severe food insecurity were eight times more likely to also have experienced intimate partner violence in the previous 12 months, compared to women who were food secure (AOR = 8.36 95% CI = [2.29–30.57]) (Fong et al., 2016). A study of HIV positive men and women (n = 720) from Kenya identified a relationship between family violence and food insecurity, with most of the women surveyed (57.6%) experiencing intimate partner violence and most of the men (58.4%) perpetrating the violence (Hatcher et al., 2021). Those who reported being victims of, or perpetrating, domestic violence also reported higher household food insecurity scores compared with those without violence (21.8 vs 21.3, p = 0.02)(Hatcher et al., 2021). Similarly, a study by Diamond-Smith et al., (2019) of Nepalese women found that severe food insecurity was significantly associated with the experience of emotional abuse (OR = 1.75, 95% CI = 1.06–2.77) or physical abuse (OR = 2.48, 95% CI = 1.52–4.04). That this pattern of behaviour has been experienced globally, by people from vastly different individual circumstances, speaks to the likely relationship between household stressors and household conflict (Buller et al., 2016; Capaldi et al., 2012). Further examination of the relationship between the experiences of food insecurity and family violence in low- and middle-income countries could be explored in additional research.

Food insecurity is one of many outcomes of financial insecurity and stressors, with financial stress, job loss, or housing insecurity associated with psychological distress (Taylor et al., 2017). Financial stress has also been found to contribute to difficulties with self-care, pain, anxiety, and depression (French & McKillop, 2017). These factors have been conceptualised in the ‘family stress model’ which describes how economic disadvantage triggers perceived economic pressure, leading to psychological distress (Conger et al., 1992). The family stress model has previously been used in studies examining the predictors of family violence, including economic hardship (Lucero et al., 2016). After controlling for variables, the longitudinal study of 941 women found that those who experienced high levels of economic hardship over time had the highest odds of experiencing family violence when compared with women who did not experience economic hardship. As previous studies have shown, adverse events such as job loss or extreme financial insecurity cause a similar amount of stress or trauma as natural disasters (Parkinson, 2019; Parkinson & Zara, 2013)events being shown to cause an increase in family violence (Sety et al., 2014). Witnessing or experiencing family violence as a child, is significantly associated with continuing the ‘cycle of violence’ through perpetrating intimate partner violence as an adult, or continued victimisation (Jung et al., 2018; Manchikanti Gómez, 2010). In the studies included in this review, the experience of food insecurity and material deprivation appeared to lead to family violence. While parents often seek to protect children from experiencing food insecurity, not all children in households with food insecurity are protected (Parekh et al., 2021; Sun et al., 2016).

Only three studies included in this review discussed the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. These studies reported that food insecurity increased due to the pandemic, but family violence did not. This is in contrast a meta-analysis of published domestic violence data from multiple countries, finding that domestic violence increased during the “stay at home orders” during the pandemic, though the evidence was somewhat limited due to relying on officially reported crime statistics (Piquero et al., 2021). Considering that family violence disclosures to police are often underreported, the true magnitude of family violence is likely to be larger than reported (Gracia, 2004). In contrast to the studies included in our review, the significant economic, social, and physical effects of the pandemic were found to have an impact on both food insecurity and domestic violence in middle income countries (Abrahams et al., 2022; Hamadani et al., 2020). A 2020 study of South African women found that they had significantly greater odds of experiencing psychological distress during lockdowns if they were concerned that they had less food in their household (OR = 2.24, 95% CI = 1.52–3.31), they were experiencing severe food insecurity during lockdown (OR = 2.39, 95% CI = 1.76, 3.25), or if they had experienced physical abuse in the previous 12 months (OR = 2.77, 95% CI = 1.86–4.11) (Abrahams et al., 2022). Similarly, a study of Bangladeshi women found that household food insecurity rose from 8.2% of the sample to 51.8% during stay at home orders, and 56% of victims reported an increase in physical domestic violence (Hamadani et al., 2020). The novel nature of the Covid-19 pandemic means that as research is continuing, in time a better understanding of the effects of lockdowns and stay at home orders on family violence and food insecurity may emerge that aligns the experiences of those living in high income countries with those reported in middle incomes countries.

A majority (n = 28) of studies were from the USA. Food insecurity is experienced by 10.2% of the US population (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2021) and policy measures targeting food insecurity and hunger have been in place since the 1930s (Landers, 2007). The two main programmatic responses to food insecurity are the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) (Landers, 2007). Despite previous studies demonstrating the impacts of SNAP and WIC on reducing food insecurity (Mabli & Ohls, 2015), particularly among children (Mabli & Worthington, 2014), most (n = 21) of the studies from the USA did not include a measurement of participation in SNAP or WIC in their methodology. Studies that did report on participation in a nutrition assistance program had mixed findings, with four studies reporting that most food insecure participants did use SNAP benefits, and three studies reporting that food insecure participants did not use SNAP benefits. Both findings are relevant. Participants reporting that they are not utilising SNAP or other nutrition assistance indicates that they have not engaged with the SNAP benefit program, despite their situation. Previous studies have identified many reasons for not engaging with nutrition assistance programs, including feelings of judgement and mistreatment by society (Chilton et al., 2009) and insufficient outreach programs (Fricke et al., 2015). Vulnerable populations, such as those at the focus of this review, are an important target for SNAP benefits as they are likely to meet the low income eligibility requirements (Landers, 2007). In food insecure populations, gaining SNAP benefits has shown a reduced probability of depression compared to those without nutrition assistance (Munger et al., 2016). Additionally, many of the studies examined in this review feature households with children. Children who participate in SNAP or WIC programs in childhood have a four times greater odds of being food secure as adults than children whose households are eligible but do not participate (Insolera et al., 2022). Four studies in this review reported that food insecure participants were accessing SNAP benefits. Individuals who are receiving SNAP benefits but still reporting experiencing food insecurity may be indicative that the program is insufficient to meet their needs. Criticisms of SNAP have included perceptions that the income testing required for eligibility is unrealistic and is too low when considering the costs of living, especially of raising children (Gaines-Turner et al., 2019). Additionally, previous studies have reported participants refusing extra work or an increase in pay as the small increase would mean they were no longer eligible for SNAP benefits (Ettinger de Cuba et al., 2019; Gaines-Turner et al., 2019).

Most of the studies reported in this review use quantitative methodology. Complex social phenomena such as food insecurity or family violence likely require deeper investigation than is possible through quantitative methods, as the causes and experiences have variations between individuals (Silverman, 2006). The flexibility of qualitative methods allows for participants to share their experiences without the potential interference of preconceived ideas from the researcher (Prosek & Gibson, 2021). Lived experience methodology have previously been used in studies examining domestic violence (Loke et al., 2012; Taylor et al., 2001), and food insecurity (Connors et al., 2020; Laraia, 2013) so may also be appropriate for a study involving both subjects. Individuals who are experiencing challenging personal circumstances such domestic violence or food insecurity can be difficult populations to involve in research as these occurrences are often kept secret or hidden due to perceived judgement or shame (Overstreet & Quinn, 2013; Purdam et al., 2015), so methods such as lived experience may appeal to them as an avenue of sharing their story. Conversely, the relative anonymity of a survey may also appeal to such individuals, which may explain why so many studies included in this review chose this method of data collection. Future research that delves into the diverse experiences of individuals, particularly women as they make up the majority of those who experience domestic violence (World Helath Organization, 2021), is necessary to better understand the complex associations between food insecurity and family violence. Particularly, there is a lack of research examining the resilience and recovery of family violence victims in the wake of disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic (Sety et al., 2014).

These findings highlight the important role of agencies to consider both food insecurity and family violence. During the Covid-19 pandemic, emergency and community food providers reported an increase in the number of people who were seeking food assistance and reporting family violence (Abrahams et al., 2022; Hamadani et al., 2020), with some research suggesting this was related to perpetrators having greater access to their domestic partners due to stay at home orders (Anurudran et al., 2020; Kourti et al., 2021). With pandemic restrictions now all largely lifted, new research is needed to explore if the increase in people presenting at food charities due to intimate partner and family violence will recede, or if this trend continues.

Limitations

There are some limitations of this review that must be acknowledged. While every attempt was made to ensure this review was comprehensive, it is possible that articles have been missed. In particular, one key limitation that needs to be addressed relates to the search terms. The scoping review nature of this work means the search terms related only to a general definition of family violence. Other search terms, such as child mistreatment, abuse, or maltreatment, may have resulted in a larger number of studies. However, given this is the first review of its kind, with the inclusion of several databases and a range of broad key terms, the authors are confident that much of the available information is presented here. Given the largely heterogeneous nature of the inquiry into food insecurity and family violence, the authors decided to present this as a narrative review and have not sought to present a meta-analysis.

Conclusion

Food insecurity and family violence are significant societal problems, with evidence that both have increased in prevalence and severity due to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. This review provides initial evidence for a bi-directional relationship between food insecurity and family violence in high income countries. Populations experiencing food insecurity and family violence are both vulnerable and hard to reach, so gaining a clear understanding of their experiences is difficult. Future studies and policy making decisions will require the engagement of these communities to ensure that proposed supports and solutions are appropriate and will be effective .

References

Abdurahman, A. A., Chaka, E. E., Nedjat, S., Dorosty, A. R., & Majdzadeh, R. (2019). The association of household food insecurity with the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Nutrition, 58(4), 1341–1350.

Abrahams, Z., Boisits, S., Schneider, M., Prince, M., & Lund, C. (2022). The relationship between common mental disorders (CMDs), food insecurity and domestic violence in pregnant women during the COVID-19 lockdown in Cape Town, South Africa. Social Psychiatry And Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-021-02140-7

Adhia, A., Lyons, V. H., Cohen-Cline, H., & Rowhani-Rahbar, A. (2020). Life experiences associated with change in perpetration of domestic violence. Injury Epidemiology, 7(1), 37. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-020-00264-z

Anderson, M. A., Gillig, P. M., Sitaker, M., McCloskey, K., Malloy, K., & Grigsby, N. (2003). “Why Doesn’t She Just Leave?”: A Descriptive Study of Victim Reported Impediments to Her Safety. Journal of Family Violence, 18(3), 151–155. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023564404773

Anurudran, A, Yared, L, Comrie, C, Harrison, K, & Burke, T. (2020). Domestic violence amid COVID-19 [https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13247]. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 150(2) 255–256 https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13247

Augusto, A. L. P., de Abreu Rodrigues, A. V., Domingos, T. B., & Salles-Costa, R. (2020). Household food insecurity associated with gestacional and neonatal outcomes: A systematic review. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 20, 1–11.

Barreto, D., Shoveller, J., Braschel, M., Duff, P., & Shannon, K. (2019). The effect of violence and intersecting structural inequities on high rates of food insecurity among marginalized sex workers in a Canadian setting. Journal of Urban Health, 96(4), 605–615.

Black, M. C., Basile, K. C., Breiding, M. J., Smith, S. G., Walters, M. L., Merrick, M. T., Chen, J., & Stevens, M. R. (2011). The national intimate partner and sexual violence survey (NISVS): 2010 summary report. https://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/NISVS_Report2010-a.pdf. Accessed 18 Aug 2023

Brandhorst, S, & Clark, DL. (2022). Food security for survivors of intimate partner violence: Understanding the role of food in survivor well-being. Health Soc Care Community. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.14064

Breiding, M. J., Basile, K. C., Klevens, J., & Smith, S. G. (2017). Economic Insecurity and Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Victimization. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(4), 457–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2017.03.021

Buller, A. M., Hidrobo, M., Peterman, A., & Heise, L. (2016). The way to a man’s heart is through his stomach?: a mixed methods study on causal mechanisms through which cash and in-kind food transfers decreased intimate partner violence. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 488. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3129-3

Burns, C. (2004). A review of the literature describing the link between poverty, food insecurity and obesity with specific reference to Australia. Melbourne, Australia: VicHealth.

Caetano, R., Cunradi, C. B., Alter, H. J., Mair, C., & Yau, R. K. (2019). Drinking and Intimate Partner Violence Severity Levels Among U.S. Ethnic Groups in an Urban Emergency Department. Academic Emergency Medicine, 26(8), 897–907. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13706

Capaldi, D. M., Knoble, N. B., Shortt, J. W., & Kim, H. K. (2012). A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse, 3(2), 231–280.

Chilton, M., & Booth, S. (2007). Hunger of the body and hunger of the mind: African American women’s perceptions of food insecurity, health and violence. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 39(3), 116–125.

Chilton, M., Rabinowich, J., Council, C., & Breaux, J. (2009). Witnesses to hunger: Participation through photovoice to ensure the right to food. Health and Human Rights, 11(1), 73–85.

Chilton, M. M., Rabinowich, J. R., & Woolf, N. H. (2014). Very low food security in the USA is linked with exposure to violence. Public Health Nutrition, 17(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980013000281

Chilton, M., Knowles, M., Rabinowich, J., & Arnold, K. T. (2015). The relationship between childhood adversity and food insecurity:‘It’s like a bird nesting in your head.’ Public Health Nutrition, 18(14), 2643–2653.

Chilton, M., Knowles, M., & Bloom, S. L. (2017). The intergenerational circumstances of household food insecurity and adversity. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 12(2), 269–297.

Clark, D., & Jordan, R. (2022). Recognizing Resilience: Exploring the Impacts of COVID-19 on Survivors of Intimate Partner Violence. Gender Issues, 39(3), 320–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12147-021-09292-5

Conger, R. D., Conger, K. J., Elder, G. H., Jr., Lorenz, F. O., Simons, R. L., & Whitbeck, L. B. (1992). A family process model of economic hardship and adjustment of early adolescent boys. Child Development, 63(3), 526–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1992.tb01644.x

Connors, C., Malan, L., Canavan, S., Sissoko, F., Carmo, M., Sheppard, C., & Cook, F. (2020). The lived experience of food insecurity under Covid-19. A bright Harbour collective report for the food standards agency. London, UK.

Conroy, A. A., Cohen, M. H., Frongillo, E. A., Tsai, A. C., Wilson, T. E., Wentz, E. L., Adimora, A. A., Merenstein, D., Ofotokun, I., Metsch, L., Kempf, M. C., Adedimeji, A., Turan, J. M., Tien, P. C., & Weiser, S. D. (2019). Food insecurity and violence in a prospective cohort of women at risk for or living with HIV in the US. PLoS ONE, 14(3), e0213365. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0213365

Crandall, A. K., Temple, J. L., & Kong, K. L. (2020). The association of food insecurity with the relative reinforcing value of food, BMI, and gestational weight gain among pregnant women. Appetite, 151, 104685. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104685

Cunradi, CB, Ponicki, WR, Caetano, R, & Alter, HJ. (2020). Frequency of Intimate Partner Violence among an Urban Emergency Department Sample: A Multilevel Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010222

Dallman, M. F., Pecoraro, N., Akana, S. F., la Fleur, S. E., Gomez, F., Houshyar, H., Bell, M. E., Bhatnagar, S., Laugero, K. D., & Manalo, S. (2003). Chronic stress and obesity: A new view of “comfort food.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(20), 11696–11701. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1934666100

Daundasekara, S. S., Schuler, B., & Hernandez, D. C. (2022). Independent and combined associations of intimate partner violence and food insecurity on maternal depression and generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 87, 102540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102540

Demétrio, F., Teles, CAd. S., Santos, DBd., & Pereira, M. (2020). Food insecurity in pregnant women is associated with social determinants and nutritional outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 25, 2663–2676.

Diamond-Smith, N., Conroy, A. A., Tsai, A. C., Nekkanti, M., & Weiser, S. D. (2019). Food insecurity and intimate partner violence among married women in Nepal. Journal of Global Health, 9(1), 010412. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.09.010412

Dinour, L. M., Bergen, D., & Yeh, M.-C. (2007). The Food Insecurity Obesity Paradox: A Review of the Literature and the Role Food Stamps May Play. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(11), 1952–1961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.006

Drewnowski, A. (2009). Obesity, diets, and social inequalities. Nutrition Reviews, 67(suppl_1), S36–S39. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00157.x

Dubois, L, Francis, D, Burnier, D, Tatone-Tokuda, F, Girard, M, Gordon-Strachan, G, Fox, K, & Wilks, R. (2016). Household food insecurity and childhood overweight in Jamaica and Quebec: a gender-based analysis. In Food Security and Child Malnutrition (195–216). Apple Academic Press.

Ettinger de Cuba, S., Chilton, M., Bovell-Ammon, A., Knowles, M., Coleman, S. M., Black, M. M., Cook, J. T., Cutts, D. B., Casey, P. H., Heeren, T. C., & Frank, D. A. (2019). Loss Of SNAP Is Associated With Food Insecurity And Poor Health In Working Families With Young Children. Health Affairs, 38(5), 765–773. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05265

FAO. (2013). The State of Food Insecurity in the World 2013; The multiple dimensions of food security. Food and agriculture organization. http://www.fao.org/docrep/018/i3434e/i3434e.pdf

FAO. (2021). Hunger and food insecurity. https://www.fao.org/hunger/en/

FAO, IFAD, UNICEF, WFP, & WHO. (2022). The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. https://www.fao.org/publications/sofi/en/

Fedina, L., Ashwell, L., Bright, C., Backes, B., Newman, M., Hafner, S., & Rosay, A. B. (2022a). Racial and Gender Inequalities in Food, Housing, and Healthcare Insecurity Associated with Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(23–24), Np23202-np23221. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221077231

Fedina, L., Peitzmeier, S. M., Ward, M. R., Ashwell, L., Tolman, R., & Herrenkohl, T. I. (2022b). Associations between intimate partner violence and increased economic insecurity among women and transgender adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychology of Violence, No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000429

Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing, 24(4), 230–235. https://doi.org/10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

Fong, S, Gupta, J, Kpebo, D, & Falb, K. (2016). Food insecurity associated with intimate partner violence among women in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.03.012]. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 134(3), 341–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2016.03.012

French, D., & McKillop, D. (2017). The impact of debt and financial stress on health in Northern Irish households. Journal of European social policy, 27(5), 458–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928717717657

Fricke, H. E., Hughes, A. G., Schober, D. J., Pinard, C. A., Bertmann, F. M. W., Smith, T. M., & Yaroch, A. L. (2015). An Examination of Organizational and Statewide Needs to Increase Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) Participation. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 10(2), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2015.1004217

Gaines-Turner, T., Simmons, J. C., & Chilton, M. (2019). Recommendations From SNAP Participants to Improve Wages and End Stigma. American Journal of Public Health, 109(12), 1664–1667. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305362

Garner, A., Shonkoff, J., Child, Co. PAo., & Health, F. (2012). Section on Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. Early childhood adversity, toxic stress, and the role of the pediatrician: translating developmental science into lifelong health. Pediatrics, 129(1), e224–e231.

Goldstein, R. F., Abell, S. K., Ranasinha, S., Misso, M., Boyle, J. A., Black, M. H., Li, N., Hu, G., Corrado, F., & Rode, L. (2017). Association of gestational weight gain with maternal and infant outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of American Medical Association, 317(21), 2207–2225.

Goodman, L. A., Smyth, K. F., Borges, A. M., & Singer, R. (2009). When crises collide: How intimate partner violence and poverty intersect to shape women’s mental health and coping? Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 10(4), 306–329.

Gracia, E. (2004). Unreported cases of domestic violence against women: Towards an epidemiology of social silence, tolerance, and inhibition. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 58(7), 536–537. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.019604

Gulliver, P., Fanslow, J., Fleming, T., Lucassen, M., & Dixon, R. (2018). Uneven progress in reducing exposure to violence at home for New Zealand adolescents 2001–2012: A nationally representative cross-sectional survey series. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 42(3), 262–268.

Gundersen, C., & Ziliak, J. P. (2015). Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Affairs, 34(11), 1830–1839.

Hall, K. D., Ayuketah, A., Brychta, R., Cai, H., Cassimatis, T., Chen, K. Y., Chung, S. T., Costa, E., Courville, A., Darcey, V., Fletcher, L. A., Forde, C. G., Gharib, A. M., Guo, J., Howard, R., Joseph, P. V., McGehee, S., Ouwerkerk, R., Raisinger, K., … Zhou, M. (2019). Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell Metab, 30(1), 67-77.e63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008

Hamadani, J. D., Hasan, M. I., Baldi, A. J., Hossain, S. J., Shiraji, S., Bhuiyan, M. S. A., Mehrin, S. F., Fisher, J., Tofail, F., Tipu, S. M. M. U., Grantham-McGregor, S., Biggs, B.-A., Braat, S., & Pasricha, S.-R. (2020). Immediate impact of stay-at-home orders to control COVID-19 transmission on socioeconomic conditions, food insecurity, mental health, and intimate partner violence in Bangladeshi women and their families: an interrupted time series. The Lancet Global Health, 8(11), e1380–e1389. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30366-1

Hatcher, A. M., Weiser, S. D., Cohen, C. R., Hagey, J., Weke, E., Burger, R., Wekesa, P., Sheira, L., Frongillo, E. A., & Bukusi, E. A. (2021). Food Insecurity and Intimate Partner Violence Among HIV-Positive Individuals in Rural Kenya. American journal of preventive medicine, 60(4), 563–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.025

Hegarty, K., Hindmarsh, E. D., & Gilles, M. T. (2000). Domestic violence in Australia: Definition, prevalence and nature of presentation in clinical practice. The Medical Journal of Australia, 173(7), 363–367.

Helton, J. J., Jackson, D. B., Boutwell, B. B., & Vaughn, M. G. (2019). Household Food Insecurity and Parent-to-Child Aggression. Child Maltreatment, 24(2), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559518819141

Hernandez, D. C., Marshall, A., & Mineo, C. (2014). Maternal depression mediates the association between intimate partner violence and food insecurity. Journal of Womens Health (Larchmt), 23(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2012.4224

Holben, D. H., & Marshall, M. B. (2017). Position of the academy of nutrition and dietetics: Food insecurity in the United States. Journal of the Academy of Nutrition Dietetics, 117(12), 1991–2002.

Humphreys, C., & Thiara, R. (2003). Mental health and domestic violence:‘I call it symptoms of abuse.’ British Journal of Social Work, 33(2), 209–226.

Hunt, B. R., Benjamins, M. R., Khan, S., & Hirschtick, J. L. (2019). Predictors of Food Insecurity in Selected Chicago Community Areas. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 51(3), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneb.2018.08.005

Idzerda, L., Gariépy, G., Corrin, T., Tarasuk, V., McIntyre, L., Neil-Sztramko, S., Dobbins, M., Snelling, S., & Garcia, A. J. (2022). Evidence synthesis What is known about the prevalence of household food insecurity in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 42(5), 177–187.

Insolera, N., Cohen, A., & Wolfson, J. A. (2022). SNAP and WIC Participation During Childhood and Food Security in Adulthood, 1984–2019. American Journal of Public Health, 112(10), 1498–1506. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2022.306967

Jackson, D. B., Lynch, K. R., Helton, J. J., & Vaughn, M. G. (2018). Food insecurity and violence in the home: Investigating exposure to violence and victimization among preschool-aged children. Health Education & Behavior, 45(5), 756–763.

Jayedi, A., Soltani, S., Abdolshahi, A., & Shab-Bidar, S. (2020). Healthy and unhealthy dietary patterns and the risk of chronic disease: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of prospective cohort studies. British Journal of Nutrition, 124(11), 1133–1144. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007114520002330

Jung, H., Herrenkohl, T. I., Skinner, M. L., Lee, J. O., Klika, J. B., & Rousson, A. N. (2018). Gender Differences in Intimate Partner Violence: A Predictive Analysis of IPV by Child Abuse and Domestic Violence Exposure During Early Childhood. Violence Against Women, 25(8), 903–924. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801218796329

Kim, H., Gundersen, C., & Windsor, L. (2022). Community food insecurity predicts child maltreatment report rates across Illinois zip codes 2011–2018. Annals of epidemiology, 73, 30–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2022.06.002

Kourti, A, Stavridou, A, Panagouli, E, Psaltopoulou, T, Spiliopoulou, C, Tsolia, M, Sergentanis, TN, & Tsitsika, A. (2021). Domestic Violence During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 0(0), 15248380211038690. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380211038690

Krause, KH, DeGue, S, Kilmer, G, & Niolon, PH. (2022). Prevalence and correlates of non-dating sexual violence, sexual dating violence, and physical dating violence victimization among US high school students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey, United States, 2021. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 08862605221140038.

Landers, P. S. (2007). The Food Stamp Program: History, Nutrition Education and Impact. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 107(11), 1945–1951. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2007.08.009

Laraia, B. A. (2013). Food insecurity and chronic disease. Advances in Nutrition, 4(2), 203–212.

Laraia, B. A., Siega-Riz, A. M., & Gundersen, C. (2010). Household Food Insecurity Is Associated with Self-Reported Pregravid Weight Status, Gestational Weight Gain, and Pregnancy Complications [Article]. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 110(5), 692–701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2010.02.014

Laraia, B. A., Gamba, R., Saraiva, C., Dove, M. S., Marchi, K., & Braveman, P. (2022). Severe maternal hardships are associated with food insecurity among low-income/lower-income women during pregnancy: results from the 2012–2014 California maternal infant health assessment. BMC pregnancy and childbirth, 22(1), 138. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-022-04464-x

Laurenzi, C., Field, S., & Honikman, S. (2020). Food insecurity, maternal mental health, and domestic violence: A call for a syndemic approach to research and interventions. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 24(4), 401–404.

Leddy, A. M., Zakaras, J. M., Shieh, J., Conroy, A. A., Ofotokun, I., Tien, P. C., & Weiser, S. D. (2021). Intersections of food insecurity, violence, poor mental health and substance use among US women living with and at risk for HIV: Evidence of a syndemic in need of attention. PLoS ONE, 16(5), e0252338. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252338

Lim, S., Park, J. N., Kerrigan, D. L., & Sherman, S. G. (2019). Severe Food Insecurity, Gender-Based Violence, Homelessness, and HIV Risk among Street-based Female Sex Workers in Baltimore, Maryland. AIDS Behavior, 23(11), 3058–3063. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-019-02643-0

Liu, Y., & Eicher-Miller, H. A. (2021). Food insecurity and cardiovascular disease risk. Current Atherosclerosis Reports, 23(6), 1–12.

Loke, A. Y., Wan, M. L. E., & Hayter, M. (2012). The lived experience of women victims of intimate partner violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 21(15–16), 2336–2346.

Lucero, J. L., Lim, S., & Santiago, A. M. (2016). Changes in Economic Hardship and Intimate Partner Violence: A Family Stress Framework. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 37(3), 395–406. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-016-9488-1

Mabli, J., & Ohls, J. (2015). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation Is Associated with an Increase in Household Food Security in a National Evaluation. The Journal of Nutrition, 145(2), 344–351. https://doi.org/10.3945/jn.114.198697

Mabli, J., & Worthington, J. (2014). Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program Participation and Child Food Security. Pediatrics, 133(4), 610–619. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-2823

Manchikanti Gómez, A. (2010). Testing the Cycle of Violence Hypothesis: Child Abuse and Adolescent Dating Violence as Predictors of Intimate Partner Violence in Young Adulthood. Youth & Society, 43(1), 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X09358313

Martin, A. J., Berenson, K. R., Griffing, S., Sage, R. E., Madry, L., Bingham, L. E., & Primm, B. J. (2000). The process of leaving an abusive relationship: The role of risk assessments and decision-certainty. Journal of Family Violence, 15, 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1007515514298

Maynard, M., Andrade, L., Packull-McCormick, S., Perlman, C. M., Leos-Toro, C., & Kirkpatrick, S. I. (2018). Food insecurity and mental health among females in high-income countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(7), 1424.

McKay, F, McKenzie, H, & Lindberg, R. (2023). The coping continuum and acts reciprocity – a qualitative enquiry about household coping with food insecurity in Victoria, Australia. ANZJPH, 47(1), 100004.

Melchior, M., Caspi, A., Howard, L. M., Ambler, A. P., Bolton, H., Mountain, N., & Moffitt, T. E. (2009). Mental health context of food insecurity: a representative cohort of families with young children. Pediatrics, 124(4), e564-572. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0583

Montgomery, B. E., Rompalo, A., Hughes, J., Wang, J., Haley, D., Soto-Torres, L., Chege, W., Justman, J., Kuo, I., Golin, C., Frew, P., Mannheimer, S., & Hodder, S. (2015). Violence Against Women in Selected Areas of the United States. American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), 2156–2166. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2014.302430

Moradi, S., Mirzababaei, A., Dadfarma, A., Rezaei, S., Mohammadi, H., Jannat, B., & Mirzaei, K. (2019). Food insecurity and adult weight abnormality risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Nutrition, 58(1), 45–61.

Munger, A. L., Hofferth, S. L., & Grutzmacher, S. K. (2016). The Role of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program in the Relationship Between Food Insecurity and Probability of Maternal Depression. Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition, 11(2), 147–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2015.1045672

Murray, C., Crowe, A., & Akers, W. (2016). How Can We End the Stigma Surrounding Domestic and Sexual Violence? A Modified Delphi Study with National Advocacy Leaders. Journal of Family Violence, 31(3), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9768-9

Murthy, V. (2016). Food Insecurity: A Public Health Issue. Public Health Reports, 131(5), 655–657. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354916664154

Nunnery, D., Ammerman, A., & Dharod, J. (2018). Predictors and outcomes of excess gestational weight gain among low-income pregnant women. Health Care for Women International, 39(1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2017.1391263

Ohtsuka, MS, Shannon, K, Zucchet, A, Krüsi, A, Bingham, B, King, D, Axl-Rose, T, Braschel, M, & Deering, KN. (2022). Prevalence and Social-Structural Correlates of Gender-Based Violence Against Women Living With HIV in Metro Vancouver, Canada. J Interpers Violence, 8862605221118611. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221118611

Overstreet, N. M., & Quinn, D. M. (2013). The Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization Model and Barriers to Help Seeking. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(1), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.746599

Parekh, N., Ali, S. H., O’Connor, J., Tozan, Y., Jones, A. M., Capasso, A., Foreman, J., & DiClemente, R. J. (2021). Food insecurity among households with children during the COVID-19 pandemic: results from a study among social media users across the United States. Nutrition Journal, 20(1), 73. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12937-021-00732-2

Parkinson, D. (2019). Investigating the increase in domestic violence post disaster: An Australian case study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(11), 2333–2362.

Parkinson, D., & Zara, C. (2013). The hidden disaster: Domestic violence in the aftermath of natural disaster [Other Journal Article]. The Australian Journal of Emergency Management, 28(2), 28–35. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.364519372739042

Piquero, A. R., Jennings, W. G., Jemison, E., Kaukinen, C., & Knaul, F. M. (2021). Domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic - Evidence from a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Criminal Justice, 74, 101806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2021.101806

Power, E. M. (2006). Economic abuse and intra-household inequities in food security. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 97(3), 258–260. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03405600

Prosek, EA, & Gibson, DM. (2021). Promoting Rigorous Research by Examining Lived Experiences: A Review of Four Qualitative Traditions [https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12364]. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(2), 167–177 https://doi.org/10.1002/jcad.12364

Purdam, K., Garratt, E. A., & Esmail, A. (2015). Hungry? Food Insecurity, Social Stigma and Embarrassment in the UK. Sociology, 50(6), 1072–1088. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038515594092

Ricks, J. L., Cochran, S. D., Arah, O. A., Williams, J. K., & Seeman, T. E. (2016). Food insecurity and intimate partner violence against women: results from the California Women’s Health Survey. Public Health Nutrition, 19(5), 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980015001986

Schwab-Reese, L. M., Peek-Asa, C., & Parker, E. (2016). Associations of financial stressors and physical intimate partner violence perpetration. Injury Epidemiology, 3(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40621-016-0069-4

Sety, M, James, K, & Breckenridge, J. (2014). Understanding the Risk of Domestic Violence During and Post Natural Disasters: Literature Review. In L. W. Roeder (Ed.), Issues of Gender and Sexual Orientation in Humanitarian Emergencies: Risks and Risk Reduction (99–111). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-05882-5_5

Silverman, D. (2006). Interpreting qualitative data: Methods for analyzing talk, text and interaction. London, UK: Sage.

Smith, M. D., Rabbitt, M. P., & Coleman-Jensen, A. (2017). Who are the world’s food insecure? New evidence from the Food and Agriculture Organization’s food insecurity experience scale. World Development, 93, 402–412.

Sun, J., Knowles, M., Patel, F., Frank, D. A., Heeren, T. C., & Chilton, M. (2016). Childhood Adversity and Adult Reports of Food Insecurity Among Households With Children. American journal of preventive medicine, 50(5), 561–572. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.09.024

Tarasuk, V., Cheng, J., Gundersen, C., de Oliveira, C., & Kurdyak, P. (2018). The relation between food insecurity and mental health care service utilization in Ontario. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63(8), 557–569.

Taylor, W. K., Magnussen, L., & Amundson, M. J. (2001). The lived experience of battered women. Violence against Women, 7(5), 563–585.

Taylor, M., Stevens, G., Agho, K., & Raphael, B. (2017). The Impacts of Household Financial Stress, Resilience, Social Support, and Other Adversities on the Psychological Distress of Western Sydney Parents. International Journal of Population Research, 2017, 6310683. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/6310683

Thomas, M. K., Lammert, L. J., & Beverly, E. A. (2021). Food Insecurity and its Impact on Body Weight, Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Mental Health. Current Cardiovascular Risk Reports, 15(9), 1–9.

U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2021). Food Security Status of U.S. Households in 2021. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/

Vaughn, M. G., Salas-Wright, C. P., Naeger, S., Huang, J., & Piquero, A. R. (2016). Childhood reports of food neglect and impulse control problems and violence in adulthood. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 13(4), 389.

Veritas Health Innovation. (2022). Covidence systematic review software www.covidence.org

Waxman, E., Salas, J., Gupta, P., & Karpman, M. (2022). Food insecurity trended upward in midst of high inflation and fewer supports. Retrieved 18/08/2023 from https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2679417/food-insecurity-trended-upward-in-midst-of-high-inflation-and-fewer-supports/3702752

Weaver, L. J., & Hadley, C. (2009). Moving beyond hunger and nutrition: A systematic review of the evidence linking food insecurity and mental health in developing countries. Ecology of Food and Nutrition, 48(4), 263–284.

WHO. (2021). Violence against women. Retrieved 13/07/2023 from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

World Helath Organization. (2021). Violence Against Women. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-women

Yamawaki, N., Ochoa-Shipp, M., Pulsipher, C., Harlos, A., & Swindler, S. (2012). Perceptions of domestic violence: The effects of domestic violence myths, victim’s relationship with her abuser, and the decision to return to her abuser. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 27(16), 3195–3212. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260512441253

Zarling, A. L., Taber-Thomas, S., Murray, A., Knuston, J. F., Lawrence, E., Valles, N.-L., DeGarmo, D. S., & Bank, L. (2013). Internalizing and externalizing symptoms in young children exposed to intimate partner violence: Examining intervening processes. Journal of Family Psychology, 27(6), 945.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Author information

Authors and Affiliations