Abstract

The phenomenon of moral transformation, though important, has received little attention in virtue ethics. In this paper we propose a virtue-ethical model of moral transformation as character transformation by tracking the development of new identity-defining (‘core’) character traits, their expressions, and their priority structure, through the change in what appears as possible or impossible to the moral agent. We propose that character transformation culminates when what previously appeared as morally possible to the agent now appears impossible, i.e. unconceived and unthinkable, moving through stages of transformation where some possibilities gradually disappear while others open up. While we show an example of moral transformation towards virtue, we allow that such transformation can occur in the opposite direction, hence we make claims about ‘character traits’ rather than virtues of vices. Through the example of former slave-trader Rodrigo’s transformation in the film The Mission, we follow the parallel development of new objects of value and ways of valuing (with respect to a group of indigenous people of South America) with the closing down of the possibility of disrespecting and harming them, to the end-point of transformation, where allowing their capture is for Rodrigo both unconceived and, when conceived, unthinkable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As counterintuitive as it may appear, despite being essentially focused on moral improvement via the development of good character, virtue ethics rarely considers phenomena such as change, progress, and transformation as part of its agenda. This is not to say that virtue ethics is not interested in changes in character as such; on the contrary, it is within virtue ethics – and in particular among character education scholars committed to a neo-Aristotelian virtue ethical framework – that most contemporary discussions over moral development takes place. In particular, the field abounds with conceptual and empirically-minded theoretical and educational work on what it means to become virtuous and how to train dispositions that can remain stable over time and across situations (see, among others, Kristjánsson 2007, 2015; Sanderse 2015; Steutel and Carr 1999), to the point that it is now possible to flesh out both the basics of an independent virtue-based account of moral development – corroborated by empirical evidence – and the main stages of moral development in terms of virtue acquisition. However, within this literature, the process by which individuals undergo moral changes – be they marginal or radical ones – in the values they are committed to, and in the virtues they need to pursue and protect those values, is seldom if ever exploredFootnote 1. As Kristjánsson (2018) has it, the Aristotelian picture of moral development seems to suffer from a difficulty in accounting for epiphanic moral conversions; put another way, virtue ethicists, in most cases, offer robust accounts of virtue development, but they rarely discuss instances of progress and transformation, if we conceive the latter as radical changes whereby an already virtuous agent embraces new values, abandons the previous ones, and re-orients the virtues she possesses and/or the goals whereby those virtues are specified. This has led some virtue-sceptics to the mistaken assumption that virtue ethics – as an approach to education and moral agency – is an ethics for ‘good dogs’ (Korsgaard 2009), incapable of making sense of experiences of moral transformations and of doing justice to the need for such changes.Footnote 2

At the same time, even when moral changes of this kind are discussed in virtue ethics, it is almost always through a focus on its positive goals: what to aim for, how perception becomes clearer, how to appreciate new objects of moral consideration (see, e.g., Swanton, 2021). However, change is also change away from something. In the same way, the route to transformation does not only go through the positive path of greater understanding, refined sensibility, and moral knowledge, but also through the negative path of what is no longer available to the moral subject in the process of moral development. While it is possible to hypothesise some reasons for this neglect,Footnote 3 the consequence is that one unavoidable dimension of moral change – not what is acquired, but what is lost, and how – remains largely overlooked.

In this paper, we fill this dual gap by proposing a novel account of moral transformation in virtue ethics in terms of what possibilities become unavailable to the moral agent as a result of moral transformation.Footnote 4 To develop the account, we will explore the process of moral transformation in terms of character transformation, observing the stages of moral change as a change in the possibilities that are subjectively open to the agent, culminating in the experience of ‘moral impossibility’ as the mark of character-transformation. Moral impossibility coincides with character transformation insofar as the new traits have become (i) stable and (ii) fundamental to the individual, i.e. part of the ‘core’ of her moral identity: these core character traits, we argue, can be identified through what has now become morally impossible for the individual. In other words, we propose moral impossibility as an explanatory feature of core character traits.Footnote 5

Through this discussion we aim to show that virtue ethics can account not only for moral development, but also for genuine cases of moral transformation. By moral transformation, in turn, we mean a radical revision in the structure of one’s character, a structure whose building blocks are the core traits, and that core traits are in turn partly defined and expressed by the moral possibilities that are and are not open to the agent. Since such transformations are not, typically, sudden, we will defend a developmental path which goes from imperfect degrees of character development to full-fledged new character acquisition, and in parallel fashion from degrees of possibility to moral impossibility.

2 Beyond Silencing

In the virtue ethics literature, there exists an account of the role of possibilities in revealing character, and that is John McDowell’s idea of ‘silencing’. While two people may both do the right thing for the same reasons, McDowell argues, the difference between the virtuous and the continent person is that, for the virtuous, considerations that could have counted as reasons to do otherwise than the virtuous action were not ‘heard’, i.e. they were not regarded as reasons, while the continent could feel the pull of competing reasons but then was able to act on the correct one (McDowell 1998a, b, c). The idea of silencing has not been uncontroversial, partly because it goes against a more widely accepted rational model of moral reasoning, where an agent deliberates among available but conflicting reasons, partly because it seems to present an unreachable ideal, in which the virtuous agent is not only acting well, but is not even tempted by competing attractors (Hursthouse 1999; Swanton 2003; Jacobson 2005; Seidman 2005).

McDowell’s explanation for this phenomenon is that the virtuous agent has such a perception of the situation where the right action appears to her clearly along with the consideration that support it, and it is those considerations that become reasons for action, acting both on reason and affect to provide motivation. The considerations supporting other possible courses of action either do not appeal to the agent as giving rise to reasons to act, or they appear as motivationally inert – following Jeffrey Seidman’s helpful distinction (2005). This does not require that the virtuous agent is unaware of the other possibilities or the other considerations. It only requires the agent not to take them as reasons for action. It is important that, in other circumstances, the competing possibilities and considerations would be able to play that role for the agent.

McDowell is interested in presenting a picture of fully fledged virtue and marking a contrast in the moral psychology of virtuous and merely continent agents. What is interesting but unexplored is the process by which certain possibilities become silent for the agent. If silencing is an element of virtue, can we reconstruct the process of virtue acquisition by looking at the way in which certain possibilities become gradually quieter, until they become silent?

Furthermore (and switching metaphors), in proposing silencing, McDowell’s focus – as well as McDowell’s agent’s focus – remains on the bright side, the one illuminated by virtue which in turn places other things in the shade. But there is more to be said about the path not taken. On the one hand, there is more than one way in which something may not be present as a reason for us, including cases in which we are not moved by any attractive alternative. Tragic situations are typically of the kind where all the options are morally impossible. Hence, what is silent needs to be taken seriously in its own right, not just as a counterpart of the right choice. On the other hand, if silencing requires that we do not take something as a reason because something else appears clearly as the right option, is this phenomenon unique to virtue, or can it be extended to any case in which the otherwise possible consideration or reason is incompatible with something else that the agent feels compelled to pursue as a good?

In the moral domain, something may not be present as a reason for us in a number of different ways. To think about these ways, we can begin by considering what it takes for something to be present as a reason. McDowell discusses silencing in relation to both considerations and reasons. A consideration is something that can play the role of a reason or not: A. can take the consideration that cheating on her spouse would feel physically good as a reason to do it, or not. The consideration itself is not yet a reason. But, importantly, for the possible pleasure even to be a consideration, and then a reason, the possibility of cheating needs to also be something that A. takes seriously as a possibility for her. Possibilities are primary with respect to considerations, because something counts as a consideration if the possible action that it can be a consideration for is also open to the subject. That is why, in what follows, we will use the concepts of possibilities and impossibilities, as opposed to considerations and reasons on the one hand, and silencing on the other.

Vigani (2019), in her defence of McDowell’s silencing, makes a similar point regarding the ‘construal’ of a situation:

Each construal gives the individual access to a different set of reasons (or, perhaps, reasons to do different things), but note: that individual only gets access to those reasons via the construal. When the situation is construed as an occasion to help, then the dropped money can serve as a reason to return it to its owner. When the situation is construed as an occasion for self-enrichment, then the dropped money can serve as a reason to keep it. (243)

But these construals are presented precisely in terms of the possibilities that the agent sees in the situation. And while it is true that to see a possibility, a situation needs to be construed in a particular way, what carries the force of the reasons within the construal are the possibilities that it involves. While we agree that construal is a fitting reading of McDowell’s proposal, taking the idea of possibility and impossibility as mark of character has the further advantage of being both a situation-specific identifiable mark of character, and a general one that does not refer to any particular situation. While silencing, understood as construal, refers to the way one perceives a situation in question, possibilities can relate both to what one takes to be possible in the situation, and to the kinds of possibilities that are habitually available to their particular sensibility, or their option-generating attitudes. Someone can be a person for whom betrayal is impossible, and that, while allowing us to predict their construal of a situation where betrayal may be someone else’s first choice, is part of who they are because of what is essential to their character, beyond any specific manifestation.Footnote 6 In these cases, unlike the silencing considered by McDowell, where considerations could, in other circumstances, play the role of reasons, there are no foreseeable cases in which the course of action counts as possible for the person.Footnote 7

3 Impossibilities

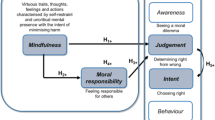

But what does it mean to take something as a possibility? In the moral domain, there are at least three broad ways in which something can be present or absent for someone as a possibility: (a) something needs to occur to me; (b) it needs to occur to me as a possibility for me, as opposed to something ‘one’ might do (i.e. the possible course of action is capable of activating the intellectual, affective, and imaginative elements that can lead to intention and action); (c) it can occur to me as something that is possible for me to do. The converse of this structure, which interests us here, is this: (a) something does not occur to me (call it the ‘unconceived’); (b) something occurs to me, or is suggested to me, but I do not take the idea seriously (it’s ‘unthinkable’) – one manifestation of this unthinkability is the fact that any consideration that would lead to this possibility is silent for me; (c) if I try to do it, I realise I cannot bring myself to do it (following Bernard Williams, this is a ‘moral incapacity’).Footnote 8 These categories can reveal something about someone’s character, in different ways, as we shall see below. Let us stress that these are subjectively perceived, moral possibilities and impossibilities, which means that they are neither possible-world concepts, nor related to what the agent understands to be possible abstractly and impersonally: they are possibilities-for-me, and, as we will show, constrained and changed by the values that define me.

However, one may note, the fact that something is not present to somebody as a possibility, in any of the ways above, is not always a mark of character, and character traits do not always give rise to impossibilities. On the one hand, possibilities are unconceived for a myriad of different reasons, from lack of information, to social conditioning, habit, culture, and so on. The experience of unthinkability, as the confusion and fear of even considering a possibility, may be the result of narrow-mindedness or prejudice. Incapacities can appear to be the result of squeamishness or phobias.Footnote 9 On the other hand, one may be courageous without finding it impossible to run away, or express one’s fairness by deciding to give the job to the most qualified person without finding it unthinkable to offer it to one’s friend. For these reasons, further distinctions are needed to put into focus more precisely the object of our claim.

Let’s start with the second worry. Character traits do not always carry with them impossibilities. At the same time, a change in character traits does not always entail a moral transformation. These two claims go together: it is only when character traits are ‘core’, i.e. (i) stable and (ii) fundamental to one’s moral identity, that their change entails a transformation of the agent; and it is these changes that, once stabilised, are related to impossibilities. Matthew Noah Smith (2010) has used the concept of ‘narrative identity’ to identify what it is that determines the range of options that are subjectively open to an agent (what we conceive, but also what we find thinkable). He concludes that the link between identity and possibility is given by the way in which the ‘practical imagination’ is only able to present to the agent possibilities that have a place within the defining aspects of one’s identity: ‘When an agent sees an action as an option, she sees it as one possible component of her narrative identity (although not under that guise). For, if an agent chooses to enact some option, she will thereby add to her narrative identity’ (18). When moral commitments define who we are, then these will be the character-defining traits that determine the limits of the moral imagination, i.e. what is conceived and, if suggested, thinkable. While the concept of ‘narrative identity’ may lead us to think that one needs to be aware of one’s life, it is not necessary for one’s core traits to be explicitly or consciously endorsed. This adds to the importance of the experience of moral impossibility as revealing core character traits that the agent, herself, may not be aware of.

The first worry was that we cannot distinguish between the possibilities that are not present to ourselves because of our character, and those that go unheard because of other limits or habits such as social conditioning or lack of imagination. It is clear that, while a possibility remains unconceived, there can be no phenomenological difference. Therefore, we suggest a test to indicate which possibilities we had not thought of due to character or other factors: unconceived possibilities are part of character when, (1) should they emerge into the open, they present themselves to the agent as ‘unthinkable’: the experience of a practical impossibility to even conceive to act against one’s character, and (2) the impossibility is accompanied by a parallel discovery, deepening, or broadening of a valueFootnote 10 which becomes part of one’s character, and with which the unthinkable act is incompatible.

If unconceived possibilities appear unthinkable once brought to the agent’s awareness, and are linked to a broadening of a value as perceived by the subject, then they qualify as possibilities that are character-defining. As suggested above, these impossibilities define not all character traits, but the ‘core’ ones of an agent, which are fundamental to her self-concept and moral identity, and are therefore not only stable, but deeply so, which means that the very idea of betraying them would amount to self-betrayal, disintegration, loss, or even ‘practical death’.Footnote 11 The agent, in other words, would feel that she is not herself anymore. We will explore both these requirements further below through a sustained example.

4 Beyond Virtue

The claims we have made so far all relate to character traits, rather than virtue. This is one last point on which we depart from McDowell. For the sake of our discussion, what matters is the ways in which possibilities open up and close down to the agent in the process of character transformation, i.e. looking at the role of experienced possibilities as marks of new stable and core character trait acquisition. There is no obvious reason why this process applies only to transformation towards virtue, rather than character transformation in general.

Even in the context of silencing, some have raised doubts that silencing of considerations and reasons is necessarily driven by virtue. One may feel the compelling salience of certain courses of action and then silence considerations leading to conflicting ones, without being right about the course of action chosen. It is enough that one considers that action to be best overall. The claim we are offering, that radical character change goes via a change in what is possible, does not require a meta-ethical commitment to the true goodness or otherwise of such values. All that our account requires is that the new character traits are (a) stable, (b) fundamental (i.e. core), and (c) constitutively connected with a specific value or set of values as perceived by the agent. While our main example revolves around a moral transformation which most readers will agree (we hope!) is for the better, we leave it open whether a similar opening up and closing down of possibility can occur in cases of transformations for the worse. Searching for possible criteria for distinguishing between the two may be possible, but it should be the matter of another paper.Footnote 12

Moreover, it is important to clarify that character transformation is not only about acquiring new traits. There are at least two other ways in which character transformation can happen without the acquisition of new traits. The first is the case of transformation which consists in exercising old traits in new ways, such as when one realises that being generous or just implies considering the needs and interests of a broader set of agents than one thought. Let us imagine a compassionate person who, after a difficult personal experience, is able to extend her compassion to people she previously was hardened to because they violated important values of hers, such as violent criminals; after a personal acquaintance with a convict, she is now able to extend her compassion to a further group. She has not acquired compassion; rather, she has applied her already established trait of compassion more fully and deeply.Footnote 13 The second case is that of a transformation which implies revising one’s way of prioritising one’s traits. This can be, e.g., the case of someone who is both truthful and respectful, but who values respect over truthfulness so much so that she would never hurt a friend with a painful truth unless strictly necessary. This person may come to realise that true respect implies a higher degree of sincerity, and that truthfulness should not be sacrificed.

With all this in mind, we need to reformulate the question posed above (§ 2), about the process that leads to silencing. Our interest lies in possibilities and character traits, both of which are broader than but include considerations and virtues. Hence, our question is the following: can we reconstruct the process of character transformation by looking at the way in which certain possibilities become gradually less open, until they become impossible for the agent? If that is possible, then moral impossibility can be helpfully used to identify and express the defining traits of character, and the dynamics of moral possibility can serve to pinpoint the process of character transformation.

5 Rodrigo’s Transformation in The Mission

As character is not static, possibilities shift, open up and narrow down, all the time. What is rarer, and worthy of consideration, is when possibilities just stop being present to the agent. That, we are arguing, is the mark of core character traits, and the endpoint of moral transformation. In order to understand not only character trait in terms of impossibility, but the process that leads to a radical change in both, and how they go hand in hand, let us now offer a description of this process through the example of Rodrigo’s transformation in Roland Joffé’s 1986 film The Mission.

The story is set in the 1750s, in the Southern American Spanish and Portuguese colonies. Its central character, played in the film by Robert De Niro, is Rodrigo Mendoza. Rodrigo is a mercenary, who makes a living kidnapping and selling native people into slavery. After one of his expeditions, he returns to the village to find out that his girlfriend is now in love with his half-brother. Rodrigo engages the brother in a duel, and in a fit of rage, kills him. After this, Rodrigo is paralysed by guilt, and in an attempt to atone for his sins, accepts to join Father Gabriel in his mission in a Guaraní community in the mountains. As he climbs the mountain, carrying a heavy burden on his shoulders containing his armour and sword as a way to punish himself, one of the natives approaches him and cuts the rope holding the armour and sword. This is a pivotal moment, when Rodrigo both sees himself as worthy of redemption, and is able to do so through the recognition bestowed upon him by the Guaraní man. At the same time, then, Rodrigo perceives the man as a helper, a fellow human being, even a friend, and feels joy and gratitude towards him – a range of perceptions and emotions he never experienced in relation to a native person. From here on, Rodrigo discovers many possibilities that were until then closed to him: that he could be friends with the Guaraní; that he could learn from them; that he could work for them, without feeling humiliated; that he could join them as family, and play with their children; possibilities that taken together disclose the fact that, now, Rodrigo has discovered a value in the Guaraní that he had not seen before. He identifies so much with the new life in the community, and with the new love he had discovered (both through spending time with the people and through reading the Bible), that he chooses to become a Jesuit.

Together with this opening of possibilities, comes a narrowing down. Rodrigo starts to feel more and more discomfort in behaviours that make little of the Guaraní’s moral worth, not only violence, but also disregard or condescension. He distances himself from those acts and attitudes, until it no longer occurs to him, not only to treat the Guaraní in the ways he formerly did, but to treat them as having anything but non-negotiable moral value. Ultimately, when the village is threatened by the Portuguese colonizers who want to capture its inhabitants, Rodrigo finds it unthinkable to let that happen. Not only is it unthinkable for him to join the Portuguese. Any possibility but that of fighting with the Guaraní to the death in a desperate attempt to defend them is now closed to him. He accepts this as his fate, with sadness but without hesitation.

Rodrigo’s reaction shows that he does not conceive of not defending the people he lives with. The possibility is unconceived, insofar as Rodrigo does not spontaneously think about it. However, it is a possibility he is rendered very much aware of through confrontation with Father Gabriel, whose values and Christian faith make it impossible for him to consider fighting and killing the Portuguese. Realising that the possibility is open to someone else, Rodrigo does not however find it thinkable not to defend the Guaraní.Footnote 14 The possibility is now clearly in his awareness, but not as a possibility – not as something that plays any role in his thinking about what to do. In fact, there is no deliberation, showing even more clearly the absence of the possibility from his mind.

Interestingly, in this instance Rodrigo’s newly acquired impossibility goes hand in hand with a discovered practical necessity – that of defending the Guaranì no matter the cost. In this example, not only one, but two overlooked and controversial dimensions of moral modality, necessity and impossibility, come to the fore. It is clear to Rodrigo that he cannot let the Guaranì be captured and that he must fight for them. Practical necessity (a notion introduced into Anglophone philosophy by Williams (1981), emerges in this case as the other side of impossibility: when everything but this action appears to me as impossible, this is what I must do. In other cases, it is the attraction of this option that makes the rest impossible, but in a different sense: not because the rest is unthinkable, but because it’s irrelevant (these are the cases most central to McDowell’s silencing). Moral impossibility and practical necessity, then, overlap in important respects. However, while we claim that moral transformation is marked by impossibilities, not all moral transformations end up in practical necessity. A core value will render what negates it impossible, but that may, and often does, still leave a range of other possibilities open to the agent.

Rodrigo’s moral transformation culminates here: in the moment when it becomes impossible for him to do what he used to do so easily, namely, to let the Guaraní lose their freedom and in some cases their lives. The impossibilities that mark his transformation satisfy our requirements for the link between impossibility and moral transformation: (1) the unconceived, once disclosed becomes unthinkable; (2) the impossibilities go hand in hand with the discovery and integration into his character of new value-related possibilities; (3) the new impossibilities and possibilities become part of his core character traits.

We can explain Rodrigo’s transformation in terms of two axes that connect the ways in which character relates to moral impossibilities. The first axis has to do with the different degrees of robustness in the possession of a character trait, and amounts to explaining the increasingly firm possession of a trait in terms of the kind of moral impossibility it involves. The second is the one, already sketched, that distinguishes between core character traits, and traits and that may be relevant to an agent, but not as crucial to their moral identity as others are. Character-based moral impossibilities require both. Character transformation requires a change in both.

5.1 Degrees of Character Traits

Since the development of character traits is incremental and admits of degrees, different degrees correspond to different kinds of (im)possibility. Rodrigo’s development corresponds to the distinction that McDowell’s silencing tracks according to the traditional Aristotelian distinction of the three main degrees of (good) character in its way to being acquired: lack of self-control (akrasia), self-control (enkrateia), and proper virtue (Sanderse 2015: 386ff). Keeping open, as we have suggested, whether the end-point applies to the acquisition of good character traits, or simply of any robust and stable character trait, the important stages remain parallel: at the first stage of development, the akratic is the one for whom nothing is morally unconceived, and of the things conceived, nothing is unthinkable. Lack of habituation, insufficiently educated emotions, and lack of self-assessing emotions such as shame and pride, impede them from ‘going practical’, i.e., internalizing their judgments when correct, and acting accordingly. Rodrigo’s slave trading life is one where love and the value of human life are up for grabs, and while he may have caring emotions, he is not able to let even love for his brother prevent him from killing him out of jealousy.

The lack of restriction in what is possible is connected with a character that has little stability and integrity. Here we follow Harry Frankfurt, who argues that limits are necessary for identity, because without them our will itself loses shape and becomes unanchored:

If the limits of choice have genuinely been wiped out, some possible courses of action will affect the person’s desires and preferences themselves and hence bring about profound changes in his volitional character… In that case, however, he will have to face his alternatives without a definitive set of goals, preferences, or other principles of choice… Any volitional characteristics that he may have prior to making that choice will be merely adventitious and provisional. (1999: 109–110)

What anchors the will, placing limits to what we can choose among, for Frankfurt, is what we love or care for. Compatibly with his account, we argue that character traits, understood as constituted by their relations to values, become stabilised and deepened the more those values become part of our identity, and the more they become part of our identity, the more some possibilities disappear for us.

Next is the self-controlled, who have overcome akrasia, but are, so to speak, on the threshold of proper character acquisition. They experience conflicting emotions, and they struggle against inclinations contrary to virtue; they are ‘almost there’, but they still find virtuous acts difficult and unpleasant. The main difference between akratic and enkratic agents is action: while akratic agents fail to act on their best judgement, the enkratics do. Therefore, from the outside, their behaviour is indistinguishable from that of the fully virtuous. Although the film does not show much of what happens between Rodrigo’s almost-epiphanic moment and his full integration with the Guaraní, we may imagine that, in the early days of life on the mission, Rodrigo could have still conceived of the possibility of Guaraní being displaced if that meant saving his and their lives. The possibility, we might imagine, was not yet dead to him. He might have listened to someone arguing for the displacement of the Guaraní, and might have understood the benefits that could bring, while disagreeing, even passionately, with the idea. Perhaps he could have argued that the Guaraní deserved some respect, so they could be displaced, but they should not be hurt. And if captured, they should be treated kindly – while not, himself, be willing to take any part whatsoever in those ventures. This is the gradual move from his previous openness to possibilities with regards to the native peoples, to a state like enkrateia or self-control, where some possibilities are still present, some accepted, some rejected but still seen as possible, as evidenced by the very fact of engaging with them and judging them wrong.

Then, as the moral worth of the Guaraní deepens within him, the possibility of acting in such a way that would destroy their home diminishes. It narrows down. Until it becomes impossible. This is parallel with McDowell’s idea of the virtuous agent’s silencing, without claiming that Rodrigo has reached full virtue. But the character traits that identify the Guaraní as equal and as family are now robust and stable within him, and those new traits, together with the new possibilities of living with them and loving them, make allowing their destruction impossible to him – unconceived, unthinkable, and therefore undoable.

We can therefore present a sketch of character development as a shift in the way an agent sees possibilities thus:

-

Conceived, thinkable, and done.

-

Conceived, thinkable, but not done (self-control).

-

Unconceived; when presented, unthinkable (and undoable).

5.2 Core and peripheral character traits

At this point, one might wonder whether this account of character and closing possibilities is too strong. After all, it is not at all true that every time we are presented with a course of action contrary to our character, we experience it as unthinkable. That is true: as we have claimed above, the character traits that issue in impossibilities need to be not only stable and robust, but also fundamental to one’s identity, or ‘core’, as opposed to peripheral character traits. Here is where our second axis comes to the fore. Moral impossibility does not come with the possession of any character trait, but only those which are perceived as most fundamental to the agent and which connect the agent to values that are fundamental to her. This is where the agent’s moral identity lies.

That moral identity is definable in terms of core character is a thesis well supported by the literature. As Aquino and Reed (2002) have it, moral identity can be defined as ‘a self-conception organized around a set of moral traits’ (1424), which ‘tends to be relatively stable over time’ (1425). In Blasi’s (1984; 1993) influential account, moral identity is, more specifically, linked to making distinctions about what is core and fundamental to our identity - which we are motivated to protect and promote - and what is peripheral and optional (Blasi and Glodis 1995).

Although there is a good amount of divergence about the exact nature of moral identity, and about the exact personological models that can better account for it, an important feature of identity, as Daniel Lapsley has argued, is a sense of integrity which is at the same time a source of practical necessity and impossibility. As we saw above with Frankfurt, integrity goes hand in hand with having limits to what one can will or desire. As Lapsley writes,

Integrity is felt as identity when we imbue the construction of self-meaning with moral desires. When constructed in this way living out one’s moral commitments does not feel like a choice but is felt instead as a matter of self-necessity. It is rather like Martin Luther at the Diet of Worms: ‘Here I stand; I can do no other.’ (2008: 37)

In sum, moral identity theory claims that some character traits protect and promote values to which one assigns the utmost importance in defining who one is. It is to those character traits that is due a sense of practical necessity, and – we argue – the closure of possibilities entrenched in the unthinkable.

We can spell out, at the risk of oversimplifying, the moral transformation of Rodrigo in terms of four fundamental changes: (1) he has a new awareness of the value of human life; (2) this value includes, centrally, the Guaraní; (3) he has a new understanding of love and of family bonds; (4) he now acts according to conscience rather than profit or self-interest, as seen for instance in his defying the Spanish governor when he demeans the Guaraní as ‘savages’.

Rodrigo’s character transformation can be explained by the establishment of a new trait that was not there before. In this case, integrity and love seem to stand out. But equally important in his character transformation is the fact that he has radically reframed previous character traits that had different values as its goals, thus effectively transforming them, although retaining their structure. We can suppose, for instance, that Rodrigo was already capable of manifestations of courage, but he had never considered the Guaraní as adequate objects of such attitude. This change – which corresponds to the first case of transformations which do not involve acquisition of new traits (see above) – can be framed in terms of what Buchanan and Powell, in their influential volume devoted to moral progress, call ‘better understandings of the virtues’ (2018: 55), i.e., the process by which one comes to revise one’s conceptualization of what it takes to be virtuous (or, in our case, to possess a certain character trait considered as a virtue) in each domain. Their example, quite fitting for our purpose, concerns the transition from a view of honour as overlapping with chastity for women, and with violent self-affirmation for men, to one which assigns priority to autonomy and rejects violence unless strictly necessary. Similarly, Rodrigo’s sense of honour goes from taking revenge for sexual betrayal, to refusing to betray the Guaraní by allowing their capture and by speaking up in their defense.

Two changes in possibility stand out to specify the acquisition of new character traits and their objects, goals, and scopes, in Rodrigo and identify it as a mark of moral transformation. One is the opening up of new possibilities, the other is the parallel narrowing and then closing down of others. On the other hand, we see the acquisition of a value, or the new formulation of a value (love, humanity), together with the new possibilities it entails (living together in the mission, defending its people), which is parallel to the narrowing down and eventual closing of possibilities that are incompatible with that value (letting them be enslaved). It is important that these two developments go hand in hand. The value of the Guaranis thus discovered becomes, over time, a stable and fundamental feature of Rodrigo’s moral identity. The other, as we have seen, is the unthinkability of the possibility now closed, should it be presented to him. In the final stage, Rodrigo does not even think about not fighting for the Guaranís. That possibility is unconceived. And it is so because even conceiving of it as a possibility would show that his valuing of the Guaraní is still unstable, or tentative. What shows that his conversion is complete is that the possibility is no longer there for him. And, when it is presented by someone else, he cannot take it seriously: he sees it as an abstract hypothetical course of action, but not as a possibility for himself.

6 Conclusion

We have argued that we can use the changes in possibilities and impossibilities as marks of moral transformation, to track the development of core character traits. Looking at character through the lens of moral impossibility, we hope to have shown, is a fruitful way to highlight the development of individual traits: from unstable and peripheral character traits corresponding to having the full range of possibilities open for consideration; to a gradual deepening of character traits in relation to a specific value, corresponding to a movement from possibilities open but rejected through deliberation, to the absence of such possibilities, either entirely absent from one’s imagination (unconceived) or present as possibilities open to others but impossible for oneself to engage in (unthinkable). It is a mark of the morally impossible that it corresponds to an opening of possibilities related to a certain value with which the absent possibility is incompatible. It is a mark of the morally unthinkable that it tends to be also unconceived, and becomes unthinkable only when an external source presents the possibility to the agent. The establishment within an agent of one or more core character traits implies gaining a different outlook, not only different actions or different deliberative conclusions. Part and parcel of that outlook is what does and what does not present itself as possible to the agent.

The impossibility that Rodrigo exhibits at the end of The Mission is one that grows out of a character transformation including both new traits (integrity and love) and new objects of these traits (the Guaraní as objects of love and part of a family). This impossibility is beautifully highlighted, in the closing dialogue of the film, through a contrast with a sham kind of impossibility.

After the Guaraní have been slaughtered, alongside Rodrigo and Father Gabriel, and the mission destroyed, the Portuguese representative Hontar discusses the facts with Cardinal Altamirano, who allowed it to happen in order to prevent the fracture in the Church that would have occurred had the Jesuits been allowed to resist.

To validate his decision, Hontar tells Altamirano: ‘You had no alternative, your Eminence. We must work in the world. The world is thus.’

Altamirano rejects the framing of impossibility. He is fully aware that his actions have been the result of a deliberate choice. A difficult one, no doubt. But one that was made between two competing possibilities, both of which he was able to survey, weighing reasons and considerations against each other. What sets his character apart from both Rodrigo and Gabriel is not that he lacked moral conscience and awareness, which he did not. It is precisely that he was not so committed to the value of life, in the form of the natives’ lives, as to be subject to the impossibility of destroying them. Refusing to hide behind a fake impossibility, Altamirano replies:

No, Señor Hontar. Thus have we made the world. Thus have I made it.’Footnote 15

Notes

This could appear in contrast with the growing amount of work in virtue and vice epistemology, which focuses on how to achieve radical changes in one’s beliefs (Cassam 2019; Kidd et al. 2021; Tanesini 2021). However, such ‘progressive’ focus seems so far almost exclusive of virtue epistemologists, rather than ethicists. Thus, even though these works have clear ethical implications, a direct discussion of changes in moral character traits is still missing. An exception within the virtue-ethical domain is represented, however, by works such as Kristjánsson 2018; Swanton 2021; Vaccarezza 2019.

For a recent accusation of conservatism, although coming from a virtue-sympathetic perspective, see Ohlhorst 2023.

One hypothesis concerns the fact that it is more inspiring, and hence more motivating, to consider the positive goal to move towards, while what is left aside does not offer the same kind of motivation. While these are psychological claims, they also contain the heritage of a Platonic idea of the good as uniquely motivating and magnetic.

We are not claiming that all moral transformation is character transformation, but we are focusing on cases where it is.

On this we follow Bernard Williams’s work on moral incapacity in taking impossibility to explain something about character, rather than vice versa (1993: 66).

Bernard Williams makes this point about impossibilities as predictors in relation to impossibilities in action, or moral incapacities.

‘Foreseeable’ is important, because we are not denying that extreme circumstances may change that, or that one may be suddenly transformed by circumstances and hence, as per our proposal, find something to be possible which was not possible before.

From the taxonomy presented in Panizza 2021.

The distinction between these and moral incapacities is at the heart of Williams 1993.

What this ‘deepening’ and ‘broadening’ mean will be explained more clearly in the next section.

We are not claiming that character disintegration is always morally undesirable. The claim is, rather, that it poses boundaries to the subject in terms of what she conceives of as possible.

The non-exclusivity of silencing to virtue has been noted e.g. by Garrard (1998), Vigani (2019), and Paul (2017). For both Garrard and Paul, silencing can occur for the vicious where considerations leading to virtuous action are silenced by their evil desires. Paul argues that silencing may in fact be the object of moral corruption, by making better alternatives invisible to the agent. While we take these points, it does not contradict that fact that silencing can be an expression of virtue; more importantly, there are strong arguments to the effect that even considering certain appalling possibilities, like genocide, is either a mark of bad faith or displays something more disturbing about the agent (see e.g. Gaita (1999), Pihlström (2009), Łukomska, (2022)).

Some might object that this person was not compassionate before, because her compassion excluded a certain group. Our reply in this case is twofold. First, virtues come in degrees, which means that an extension of the virtuous goals or targets is always possible, but someone with a sufficient grasp of virtuous targets can be already counted as virtuous. Secondly, there are situations where limited knowledge or lack of acquaintance with the relevant individuals may make the application of a virtue difficult, and ignorance about certain facts is not always culpable in the same way. In this case, the person whose compassion was limited was already fully compassionate, which is proven by the fact that after expanding her scope of experience she was able to expand her compassion to previously unlikely targets.

For both Gabriel and Rodrigo, it is impossible to leave the Guaraní to their fate: they cannot abandon them, and that impossibility stems from the recognition of their value, specifically as their right to remain in their land and be free. In the case of Rodrigo, whose passions are more local and personal than the Christian love of Gabriel (one reason why Francis is hesitant to accept Rodrigo’s desire to take vows), the impossibility also stems from recognising the Guaraní as family. So there is a shared impossibility, but with a different manifestation (fighting vs. peaceful sacrifice) because of the different scope of its source (universal love vs. particular love). Yet Rodrigo’s love is particular only up to a point, showing that he has transformed with regard to love more generally. When he kills the Portuguese, as opposed to previous killings, he is now visibly sad. His impossibility does not preclude him from seeing killing as a loss.

We would like to thank the participants at the Centre for Ethics research seminar for helpful feedback on an earlier version of this paper, as well as the editor of this journal and the two anonymous reviewers.

References

Aquino, K., and A. I. I. Reed. 2002. The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83(6): 1423–1440.

Blasi, A. 1984. Moral identity: its role in moral functioning. In Morality, moral behavior and moral development, eds. W. M. Kurtines, and J. J. Gewirtz. 128–139. New York: Wiley.

Blasi, A. 1993. The development of identity: some implications for moral functioning. In The Moral Self, eds. G. G. Noam, and T. E. Wren, 99–122. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Blasi, A., and K. Glodis. 1995. The development of identity. A critical analysis from the perspective of the self as subject. Developmental Review 15(4): 404–433.

Cassam, Q. 2019. Vices of the mind. From the intellectual to the political. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frankfurt, H. 1999. On the necessity of ideals. In Necessity, Volition, and love, 108–116. Cambridge University Press.

Gaita, R. 1999. Forms of the unthinkable. In A common humanity, 157–186. London: Routledge.

Garrard, E. 1998. The Nature of Evil. Philosophical Explorations 1: 43–60.

Hursthouse, R. 1999. On Virtue Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jacobson, D. 2005. Seeing by feeling: virtues, skills, and moral perception. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice 8: 387–409.

Kidd, I., H. Battaly, and Q. Cassam. eds. 2021. Vice Epistemology. London: Routledge.

Korsgaard, C. 2009. Self-Constitution. Agency, Identity and Integrity. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kristjánsson, K. 2007. Aristotle, emotions, and Education. London: Routledge.

Kristjánsson, K. 2015. Aristotelian Character Education. London: Routledge.

Kristjánsson, K. 2018. Epiphanic Moral conversions. Going beyond Kohlberg and Aristotle. In Self-Transcendence and Virtue. Perspectives from Philosophy, psychology, and Theology, eds. J. Frey, and C. Vogler. New York: Routledge.

Lapsley, D. 2008. Moral self-identity as the aim of education. In Handbook of Moral and Character Education, eds. L. P. Nucci, and D. Narvaez, 30–52. New York: Routledge.

Łukomska, A. 2022. Moral Evil as a ‘Thick’ ethical Concept. Studia z Historii Filozofii 13(3): 23–37.

McDowell, J. 1998a. The Role of Eudaimonia in Aristotle’s Ethics. In Mind, Value, and Reality, 3–22. Harvard University Press.

McDowell, J. 1998b. Virtue and reason. In Mind, Value, and Reality, 50–76. Harvard University Press.

McDowell, J. 1998c. Are Moral requirements hypothetical imperatives? In Mind, Value, and Reality, 77–94. Harvard University Press.

Ohlhorst, J. 2023. Engineering virtue: constructionist virtue ethics. Inquiry.

Panizza, S. 2021. Forms of Moral Impossibility. European Journal of Philosophy 30(1): 361–373.

Paul, S. 2017. Good intentions and the road to hell. Philosophical Explorations 20(2): 40–54.

Pihlström, S. 2009. Ethical unthinkabilities and philosophical seriousness. Metaphilosophy 40(5): 656–670.

Sanderse, W. 2015. An aristotelian model of Moral Development. Journal of Philosophy of Education 49(3): 382–398.

Seidman, J. 2005. Two sides of ‘Silencing’. Philosophical Quarterly 55: 68–77.

Smith, M.N. 2010. ‘Practical Imagination and its Limits’, Philosophers’ Imprint 10: 1–20.

Steutel, J., and D. Carr. 1999. Virtue Ethics and the Virtue Approach to Moral Education. In Virtue Ethics and Moral Education, eds. D. Carr, and J. Steutel. 3–18. London: Routledge.

Swanton, C. 2003. Virtue Ethics: a pluralistic view. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Swanton, C. 2021. Target Centred Virtue Ethics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tanesini, A. 2021. The mismeasure of the self: a study in Vice Epistemology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vaccarezza, M. S. 2019. Admiration, moral knowledge and transformative experiences. Humana Mente 12(35).

Vigani, D. 2019. Virtuous Construal: in defense of silencing. Journal of the American Philosophical Association: 229–245.

Williams, B. 1981. Practical necessity. In Moral Luck: philosophical papers 1973–1980, 124–131. Cambridge University Press.

Williams, B. 1993. Moral Incapacity. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, New Series 93: 59–70.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Skłodowska-Curie grant agreement No 101026701.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Caprioglio Panizza, S., Vaccarezza, M.S. Moral Transformation as Shifting (Im)Possibilities. J Ethics (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10892-024-09480-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10892-024-09480-x