Abstract

Artificial intelligence (AI) technologies are increasingly creeping into the work sphere, thereby gradually questioning and/or disturbing the long-established moral concepts and norms communities have been using to define what makes work good. Each community, and Muslims make no exception in this regard, has to revisit their moral world to provide well-thought frameworks that can engage with the challenging ethical questions raised by the new phenomenon of AI-mediated work. For a systematic analysis of the broad topic of AI-mediated work ethics from an Islamic perspective, this article focuses on presenting an accessible overview of the “moral world” of work in the Islamic tradition. Three main components of this moral world were selected due to their relevance to the AI context, namely (1) Work is inherently good for humans, (2) Practising a religiously permitted profession and (c) Maintaining good relations with involved stakeholders. Each of these three components is addressed in a distinct section, followed by a sub-section highlighting the relevance of the respective component to the particular context of AI-mediated work. The article argues that there are no unsurmountable barriers in the Islamic tradition against the adoption of AI technologies in work sphere. However, important precautions should be considered to ensure that embracing AI will not be at the cost of work-related moral values. The article also highlights how important lessons can be learnt from the positive historical experience of automata that thrived in the Islamic civilization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introductory Remarks

Robots, together with many other artificial intelligence (AI) technologies, have already found their way into different workplaces. In various instances, they can now assist or even replace human workers. Just as examples, one can refer to the order-picking robots in warehouses, the starship delivery robots that deliver items on college campuses, the robots that are assigned warfare tasks, such as the bomb disposal robots and killer robots, robots in the healthcare sector, such as the surgery robots and care robots (Smids et al. 2020: 504), in addition to the so-called robot priests that can aid the ministry of pastors and priests (Smith 2022:118). This increasingly robotized world makes part of the broader “Fourth Industrial Revolution”, which comprises automation, digitization and artificial intelligence (Brynjolfsson and McAfee 2014; Schwab 2017).

As for the Muslim world, one observes increasing interest in joining these developments, especially from the side of the oil-rich countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC)Footnote 1. As part of their urge to diversify their economies by moving from oil-based to knowledge-based economies, these countries find investing in AI technologies a great opportunity. According to estimates in published reports, AI is expected to contribute over US$135.2 billion in 2030 to the economy (equivalent to 12.4% of GDP) (PwC 2018: 4; Azar and Haddad 2021: 4). In the Saudi Vision 2030, digital transformation is identified as integral part of the national transformation strategy. In 2017, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) launched a national AI strategy, the Dubai Future Foundation launched an autonomous transportation strategy, and the world’s first AI Minister was appointed. In 2019, a dedicated AI university was established in Abu Dhabi, with specialized M.A. and PhD programs (Azar and Haddad 2021: 4). Additionally, different AI-enabled applications have found their way to different sectors. In 2020, the Dubai Health Authority (DHA) introduced “smart” robots to assist with sterilizing government-run hospitals and clinics. The AI applications also found their way to the religious domain of issuing religious advice (iftāʾ) (El Sherif 2020). The Islamic Affairs and Charitable Activities Department (IACAD), which belongs to the Government of Dubai, launched in 2019 the AI-powered ‘Virtual Ifta’ service. This service, said to be the first-of-its-kind worldwide, is available in both English and Arabic. In its first pilot phase, it was designed to answer around two hundred questions related to the topic of ritual prayer (ṣalāh), with further plans to widen the scope of the service to cover other topics, such as fasting and financial matters (Masudi 2019). In August 2019, the Saudi National Authority for Data and AI was established and it hosted a virtual Global AI Summit in October 2020Footnote 2.

These global developments continue raising tough ethical questions and challenges that necessitate revisiting people’s moral worlds and ethical frameworks at both theoretical and applied levels. Available literature shows awareness within the Muslim world of the need to address such ethical questions and associated social risks through the lens of their socio-religious values and cultural norms (Azar and Haddad 2021: 6). However, the AI principles and national strategies produced in some Muslim-majority countries could not always succeed in translating this awareness into socio-religiously sensitive documents. In 2019, Smart Dubai issued “AI Ethics Principles and Guidelines”. The document covered four main domains, namely Ethics, Security, Humanity and Inclusiveness. The document is primarily addressing the global AI community with the aim of creating commonly-agreed policies to inform the ethical use of AI, not just in Dubai but worldwide (Smart Dubai 2019: 14). With such approach that focuses on universal ethics, the document hardly contributed to showing how values rooted in the Islamic tradition, or religious values in general, would shape, or contribute to, the proposed ethical framework.

After an initial blueprint issued by the Qatar Computing Research Institute (QCRI) at Hamad Bin Khalifa University (HBKU), the National Artificial Intelligence Strategy for Qatar was published in 2019, in collaboration between the QCRI and the Ministry of Transport and Communication. This national strategy, which is available in both English and Arabic, is premised on six pillars, the sixth of which is Ethics and Public PolicyFootnote 3 (QCRI 2019: 15). The strategy called for developing “AI Ethics and Governance” that is both rooted in the local context and aligned to international norms. However, the document did not provide any substantial details about how such framework would look like, except a note in passing about Islamic philosophy, arguing that it aided the shift from sense-based to intellectual perception (QCRI 2019: 3–4, 7–8).

The latest document in this regard is the “AI Ethics Principles”, issued by the Saudi Data and Artificial Intelligence Authority in August 2022. Besides its aim to align with international standards, recommendations and overall global benchmarks, the document has also reiterated its commitment to national laws and cultural values (SDAIA 2022: 3, 7, 10–11, 16, 19). With the exception of discrete notes about considering person’s ethnic or tribal origin, religious, intellectual or political beliefs as part of the sensitive data that should not be revealed (SDAIA 2022), the document did not include much about how these cultural values would impact shaping or implementing the AI ethical principles. Unlike the Emirati and Qatari document, the Saudi document did not have a distinct section or pillar dedicated to ethics.

To sum up, Muslim communities will make no exception in people’s need to address the ethical questions triggered by the AI field. This necessitates developing ethical frameworks and approaches that are both rooted in the Islamic moral tradition and critically engaging with other religious and secular discourses. However, the state of academic scholarship on the interplay of AI and religion, in general, is still in its infancy (Dhawdī 2000; Smith 2022; Trothen 2022; Muḥaymid 2022). The religious perceptions of AI and its ethical questions, especially in world religions like Judaism, Christianity and Islam, are not only significant for those who embrace these religions but they are also essential to develop a truly diverse international discourse.

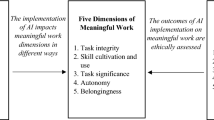

Against this background, this article is meant to fill one of the glaring lacunas in the field of AI ethics. Considering the overall theme of this thematic issue, this article will focus on examining the ethics of AI-mediated work from an Islamic perspective. After providing an overview of the governing “moral world” of good work in the Islamic tradition, the article will further analyze how such a moral world can engage with the ethical questions triggered by the particular context of AI-mediated work.

2 Moral World of Good Work

Generally speaking, the concept of work in the Islamic tradition is broader and richer than a narrow business model whose goodness/badness is governed by a thin profit-loss calculation. Good work is rather a thick and multifaceted concept that encompasses rights, obligations and moral values, while regulating power mechanisms and asymmetries. For a condensed overview of the work-related moral world in the Islamic tradition, three key elements will be highlighted in three distinct sections; namely, 1.1 Work is inherently good for humans, 1.2 Practising in a religiously permitted profession and 1.3 Maintaining good relations with involved stakeholders. To highlight the relevance of this moral world to the article’s focus, each section is followed with a dedicated sub-section entitled “Relevance to AI-mediated work”.

These three elements were thoughtfully selected because of their relevance to the modern context of AI-mediated work and because each of these elements have been widely accepted across various scholarly disciplines rooted in the Islamic tradition. However, it should be noted that no claim is made in this article that the selected elements universally represent a definitive consensus within the Islamic tradition. Some divergent views did exist, as outlined throughout the article, but they never dominated any scholarly discipline. Additionally, no claim is made that these three elements constitute the entirety of the Islamic work-related moral world. Future research on specific AI-enabled professions could entail further nuances and modifications in this regard.

2.1 Work is Inherently Good for Humans

By examining the discourse on work and labor within different Islamic scholarly disciplines, it becomes evident that there is an overall agreement on the notion that work holds intrinsic value, irrespective of possible financial gains or impact on social status. Besides the scattered discussions across various disciplines, Islamic scholarship also has a distinct genre of sources whose authors, hailing from different disciplines, have repeatedly stressed this element (Shaybānī 1980: 4–5; Setia 2016: 74). As to be shown below, each scholarly discipline employed its own mode of reasoning to highlight this element and demonstrate its compatibility with the Islamic value system.

2.1.1 Theology

Muslim theologians, representing various schools such as Muʿtazilī, Ashāʿirī, Māturīdī, and Ḥanbalī scholars, agree that one of the Islamic fundamental beliefs is that God is not only the sole Creator (khāliq) but also the sole Sustainer or sustenance provider (rāziq), in the sense that He guarantees sufficient provision (rizq), for every creature, as supported by Quranic verses such as “There is no moving creature on earth whose provision (rizq) is not guaranteed by Allah” (Q. 11:06) (Ashʿarī 2005: 1/205; ʿAbd al-Jabbār 1996: 784; Maqdisī 2011: 471–480; Saffārīnī 1982: 1/343–345).

On the other hand, most of these theologians recognized the empirical reality that provision does not automatically reach each assigned creature. Although one would sometimes effortlessly obtain money, e.g., through inheritance, the norm is that people need to exert effort in order to earn a livelihood. In this context, theologians referred to the exemplary behavior of non-human creatures, e.g., birds, ants, foxes, and spiders, which are commended in Prophetic traditions for their diligent efforts in securing their provision. Human beings, endowed with intellectual and rational capacities, are thus under obligation to be proactive and exert effort to get the provision that God has created (ʿAbd al-Jabbār 1996: 786; Ibn al-Qayyim 2011: 2/690–694).

Within this theological framework, work not only demonstrate compliance with divine guidance but also reflects a proper understanding of the natural laws that regulate human activities in this worldly life, as established by God. The required proactive stance of human beings towards work and their serious efforts to obtain provision were couched in widely-circulated terms among Muslim scholars. Arabic terms such as saʿy (diligent pursuit) and ḥaraka (literally, moving) are often featured in the titles of book on work ethics (Habīshī 1978).

Over time, a majority position emerged among theologians of different schools, holding that work is in principle good (ḥasan), and, under certain conditions, can even be considered a religious obligation. Thus, work would be deemed as a morally bad and blameworthy act only by exception, e.g., when work is pursued for the sake of excessive financial accumulation to show off. While some theologians held a minority position that work can never be a religious obligation, others went as far as considering it as a religiously forbidden act. Nonetheless, these views were consistently regarded as either representing a minority stance or simply too incoherent and ungrounded to be seriously examined. To underscore the marginality of these positions, the Muʿtazilī theologian ʿAbd al-Jabbār (d. 1025) argued that engaging in permissible professions like trade and agriculture or work in general is at the very least morally good, according to the agreement of rational people (ʿuqalāʾ) and consensus of Muslim community (umma) (ʿAbd al-Jabbār 1996: 786–787; ʿAbd al-Jabbār 1963: 11/37, 43; Maqdisī 2011: 600–606).Footnote 4

2.1.2 Jurisprudence

This discipline primarily concerns practical rulings, many of which are intended to regulate interpersonal relationships, including matters related to purchases, leases, gifts, bequeaths, work contracts, etc. Thus, the inherent value of work is so apparent and self-evident among Muslim jurists across different schools that it hardly necessitates a detailed explanation. Thus, the inherent value of work is widely recognized and embraced by Muslim jurists from various schools. While disagreements may arise regarding certain applications of this principle, the principle itself is seldom questioned or deliberated.

Briefly speaking, juristic discussions pertaining to this element of the work-related moral world can best be found within the broader discourse of jurists on the concept of maintenance (nafaqa). They agree that individuals who are capable of working have a religious obligation to engage in earning livelihood up to the extent necessary for fulfilling their basic needs, as well as the needs of those whom they are responsible for, particularly their children. The scriptural basis for this general ruling is the Prophetic tradition which reads “it is sufficient sin for a person to neglect those whom they should provide for” (Shaybānī 1980: 32–33, 44; Ibn Mufliḥ n.d.: 3/265; Wizārat 1983–2006: 41/34–100).

This ruling extends to situations when an individual needs additional income beyond the level of self-sufficiency to fulfil other financial obligations, such as repaying debts. Muslim jurists also held that even in cases of financial self-sufficiency, work is still recommended as it can enhance one’s standard of living and provide assistance for those in need (Shaybānī 1980: 57; Ibn Mufliḥ n.d.: 3/265).

2.1.3 Philosophy

As to be outlined further in this section, the writings of prominent Muslim philosophers, like Ikhwān al-Ṣafā (ca. 9th -10th century), al-Farābī (d. 950), Ibn Sīnā (d. 1037), Abū Ḥayyān al-Tawḥīdī (d. 1023), Miskawayh (1030) and others, demonstrate the considerable attention paid to work-related questions. These writings reflect wide agreement among Muslim philosophers that work and labor are not only “good” but also “necessary” for both individuals and societies at large.

As for understanding the significance of work for one’s pursuit of self-fulfillment and happiness, the correspondence between al-Tawḥīdī and Miskawayh provides important philosophical insights. Building upon the Greek understanding of human psyche (nafs), especially the famous platonic trichotomy of its concupiscent, irascible and rational powers (Fakhry 1991:112), it is argued that one’s psyche never remains idle or inactive, except during sleep. While awake, the psyche will always activate bodily organs to get engaged in either beneficial and purposeful work or in useless and aimless activity. The former is commended by rational people and mandated by political authorities, whereas the latter is prohibited by the Islamic religio-ethical system (Sharia) and reprehended by morality and etiquettes. That is why inactivity and idleness remain bad and ugly, and human reason is always averse to this behavior (Tawḥīdī and Miskawayh 2017: 273–274). In the same vein, philosophers like Ikhwān al-Ṣafā and al-Farābī held that one’s profession is part of the good life and Ibn Sīnā said political authorities must get rid of idleness and unemployment so that the city will have no unemployed person that has no specific role or position to fulfil (Ikhwān 1992: 1/284–287; Farābī 1985; 45–46 Ibn Sīnā 1957: 496, Marlow 1997: 53–64; Black 2011: 74, 76).

The significance of work and labour for society was expounded by Muslim philosophers as part of their broader political philosophy, where they wrote about the ideal state and virtuous city or utopia (al-madīna al-fāḍila). The fundamental idea reiterated in various philosophical writings is that an essential component of our human nature is that each individual inherently requires numerous things that one cannot procure independently. In order to align with this innate human nature, human societies must rely on the collaboration and unity of diverse groups who excel in a variety of crafts and develop well-regulated labour division. Labour division should be carefully regulated, not only professionally but also morally, so that producing groups can help those who cannot work because of having diseases or disabilities. Within this frame, benefits accruing from the variety of professions or crafts in society should not necessarily assume the form of material gains or financial compensation, but can assume other forms of human goodness, e.g., expressions of gratitude (Ikhwān 1992: 1/284–287; Farābī 1995: 135–137; Ibn Sīnā 1957: 497; Miskawayh n.d.: 0.37–38; Ibn Khaldūn 1988: 1/476–477).

2.1.4 Sufism

Sources from the previously examined disciplines often argued that perspectives opposing the widely accepted principle of the inherent value of work actually originate in, or come from, Sufi circles (Shaybānī 1980: 37; ʿAbd al-Jabbār 1963: 11/45 ; Maqdisī 2011: 600). Thus, this section will pay attention to these views and how they were presented and discussed within their own scholarly discipline, namely SufismFootnote 5.

One of the distinctive characteristics of Sufism is its primary occupation with the inner cultivation of spiritual virtues, such as tawakkul (trust in and, reliance on, God), waraʿ (abstinence), zuhd (detachment), etc. It seems that some Sufis struggled in balancing between enhancing these spiritual aspects and engaging in the worldly pursuit of livelihood. In his celebrated book on work ethics, the prominent Sufi master al-Muḥāsibī (d. 857) spoke about one group who argued that engaging in work and labor, as reflected in the purport of the abovementioned terms of saʿy and ḥaraka, is sinful. He referred to another group who adopted a less harsh position by arguing that work is, spiritually and morally speaking, inferior to inactivity. The main argument of both groups revolved around the concept of trust in God (tawakkul) and His guarantee for securing every creature’s provision. They argued that exerting efforts, e.g., through work, to earn provision goes contrary to the required practice of tawakkul and demonstrates that one’s trust in God is either weak or completely missing (Muḥāsibī 1992: 24, 41).

Al-Muḥāsibī provided a detailed critique of both positions, arguing that they are incompatible with the purport of key Quranic versesFootnote 6 and Prophetic traditionsFootnote 7, which instructed Muslims how to work and earn their livelihood in a religio-morally acceptable way. Additionally, he added, these positions deviated from the standard practice of morally committed Muslims, as exemplary demonstrated by the Prophet of Islam and His Companions, whose biographies show that they were always engaged in one type of work or another (Muḥāsibī 1992: 31–38, 41–47). Al-Muḥāsibī further argued that work does not contradict the concept of tawakkul, because trust in God resides in one’s heart. Thus, it falls within the domain of theoretical beliefs rather than practical behavior. Employing physical activity to earn livelihood, he explained, does not necessarily mean missing this trust but it can even reflect achieving a higher level of the required trust in God. In al-Muḥāsibī’s view, the form of tawakkul that gets both hearts (qulūb) and bodily organs (jawāriḥ) engaged in fulfilling God’s commands should, spiritually and morally speaking, be superior to the other form that involves hearts only (Muḥāsibī 1992: 45–46). It is to be noted here that al- Muḥāsibī’s reasoning is also premised on a broader perception of human nature, which implies that God created humans as “embodied beings”, and thus made their survival tied to getting sufficient food and nutrition. Hence, working to earn one’s living also reflects a proper understanding of, and respect to, the natural laws that God created (Muḥāsibī 1992: 16).

Al-Muḥāsibī’s argumentation and reasoning find resonance in the writings of other prominent Sufi masters, such as al-Ḥakīm al-Tirmidhī (d. ca. 910) and al-Ghazālī (d. 1111) (Al-Ḥakīm al-Tirmidhī 1976: 141–188; Ghazālī n.d.: 2/61–87). In his highly regarded manual, where he aimed to establish mainstream Sufi doctrines, Abū Bakr al-Kalabādhī (d. ca. 990) dedicated a section to this topic titled “Qawluhum fī al-makāsib (Their view on earnings)”. He spoke about a Sufi consensus “on the permissibility of earning through professions, trades, agriculture, and other means that are permitted by Sharia” (Kalabādhī 1960: 89). Thus, the divergent Sufi views mentioned above did not influence the prevailing position within the scholarly discipline that they belong to, let alone other scholarly disciplines.

2.1.5 Relevance to AI-mediated Work

A great deal of the ethical discourse on AI focuses on the impact of these modern technologies on the job market. Some voices warn that expanding the scope of AI-mediated work will eventually make more humans lose their jobs, certain types of work may not be available for humans in the near or far future, and some speak about incoming mass technological unemployment. Other voices hold that many AI technologies will not replace humans but just assist people in the work they already do. They add that these technologies may actually prompt a spike in new jobs and thus the total number of jobs for humans will not necessarily decrease but may even increase (WEF 2020). The analytical remarks below will not be premised on taking a position for or against one of these voices, keeping in mind that the controversy is still ongoing, with no conclusive evidence about how the future will exactly look like. The focus will be on providing relevant broad lines in the light of the information outlined in the previous section.

To start with, future plans and strategies for AI-mediated work should always keep in mind that it is essentially and inherently good for humans to have work, not only for earning livelihood but also for many other equally or more important reasons. People remain in need of work for pleasing their God, making their worldly life meaningful and securing salvation in the hereafter. Thus, it is indefensible from an Islamic ethical perspective to adopt a governing philosophy of work, in the name of improving people’s quality of life, which encourages humans to be increasingly idle, even if the working machines will make these humans more affluent. Additionally, it should be noted that some tasks and professions cannot be entrusted to AI-enabled systems or robots, even if they can outperform human skills at the technical level. This point will be clarified at the hand of the possible example of “robot imam”, viz., a robot designed to lead Muslims during their daily ritual prayers. To understand the complexity of this example, reference should be made to the central concept of people’s religious responsibility towards God (taklīf).Footnote 8 The mainstream position in Islam is that humans, unlike other creatures like animals and plants, are under obligation to worship God by performing specific religious rituals, including the five daily prayers, as part of the broader concept of taklīf. In order to fall within the category of those who are charged with taklīf, and thus become mukallaf, persons should fulfil a number of qualifications, where being alive (ḥayy) and human (ādamī)Footnote 9 always make part of these qualifications (Zarkashī 1994: 2/54–56). It is possible to design a robot that can outperform many human imams in various related tasks (e.g., good memorization of the Quran and proper recitation) but it remains untenable to argue that “robot imam” is a living human, and thus will be unfitting for this profession.

Beyond the abovementioned cautious remarks, one can safely argue that the very existence of AI-mediated work does not create inherent problems that would make it necessarily or absolutely evil or bad from an Islamic perspective. When it comes to assisting humans in their work, the use of artificial intelligence can even facilitate enhancing crucial Islamic work-related values by improving the overall performance in certain professions. According to optimistic voices like the American cardiologist, Eric Topol, medicine will be one of the good candidate professions in this regard. On one side, patients will benefit from higher levels of accuracy, productivity, and smoother workflow of available services. On the other side, assigning the time-consuming, monotonous and less innovative tasks to the AI-enabled systems will enable clinicians to dedicate more time to more complex tasks and to have better communication with their patients (Topol 2019a, b). By realizing such promised impact, the use of AI applications will be a helping factor to achieve the highly commendable value of excellence (iḥsān) in the Islamic moral tradition. Besides its moral aspect, which implies developing a virtuous character, this concept also entails mastering one’s professional skills to operate as perfectly as possible. Because of its particular relevance to those working in the healthcare sector, transnational Islamic institutions proposed incorporating iḥsān as one of the bioethical principles rooted in the Islamic tradition (Ghaly 2016: 25–26, 242, 253, 257, 280–281).

As for replacing humans at work by AI systems because of the latter’s better performance, the issue is more complex and controversial than the case of just assisting human workers. One of the main ethical concerns in this regard is that the first victims will be those who belong to the lower classes of society and earn their livelihood through work that can be efficiently automated, e.g., receptionists, retail salespersons, proofreaders, commercial couriers, etc. Replacing these human workers by more “efficient” AI-enabled systems or robots cannot be justified by creating other (new) jobs that will be in demand because of expanding the AI-mediating work, including fields like data mining, machine learning, robotics, etc. It is very unlikely that the low-skilled workers who are going to lose their jobs will be the ones who can take over the newly created jobs. (Inter)national economy may not be negatively affected, or may even get better, by these shifts. However, the actual cost will be borne by “vulnerable” groups in society, who will have to cope with joblessness for short or extended periods until the job market retains normal balance. In the Islamic moral system, having more power means bearing greater responsibility and having less power entails more protection (Zarqā 1989: 161; Ghazzī 2003: 2/459–460). The AI-created joblessness of these groups makes them more vulnerable and thus should be entitled to strong protective measures to secure their temporary financial needs and also their permanent need for meaningful work.

Despite the above-outlined serious ethical concerns that should always be carefully considered, numerous examples in Islamic and human history show that these concerns remain circumstantial in nature and do not make the very shift to AI-mediated work indiscriminately evil. One of the relevant examples in this regard is the profession of scribes (nassākhūn or warrāqūn), which thrived in the pre-modern Islamic civilization during the dominant culture of hand-written manuscripts. Besides its socio-political significance, where scribes sometimes assumed high-rank positions, the profession could also provide important religious services. By the growth of educated people, there was an increasing demand for copies of the Quran, collections of Prophetic traditions and works on Islamic scholarly disciplines. This religio-socio-political context made scribes indispensable in Muslim societies. By the introduction of the then new technology of printing in the Muslim world, it was no surprise that the scribes fiercely opposed it. The 18th -centuty scribes in Istanbul, whose number ranged between 20.000 and 90.000, carried an empty coffin with manuscript and writing tools therein and marched towards the graveyard. They wanted to express their fear that accommodating the technology of printing would result in the extermination of their profession. Within such context, different religious scholars issued fatwas against the use of printing to make copies of the Quran or religious books in general. However, when the new technology proved its efficacy, ethical concerns were addressed and the overall social reality became more accommodative. As a result, the new technology was eventually embraced in the Muslim world to the extent that Muslim scholars ended up judging it as a blessed practice (Ghaly 2009b).

2.2 Practising a Religiously Permitted Profession

As outlined in Sect. 1.1 above, the concept of provision (rizq) is tied to exercising activity. Through diligent pursuit (saʿy) and movement (ḥaraka), one can gain one’s provision. In this regard, there are religious rulings and regulations that should be followed so that the acquired provision will be judged as religiously permissible (ḥalāl) and good/pure (ṭayyib). One of the agreed upon rulings in this regard is that one’s profession (ḥirfa) should be religiously permissible in itself (Muḥāsibī 1992: 24, 29–34; Ibn Sīnā 1957: 497 − 298; ʿAbd al-Jabbār 1963: 11/33–40; Wizārat 1983–2006: 31/281–294). The general rule in this regard is outlined in the Quranic verse, “O People! Eat from what is lawful and good on the earth and do not follow Satan’s footsteps. He is truly your sworn enemy” (Q. 2: 168). Certain profit-making activities or professions are prohibited in Islam, such as gambling, prostitution and doing business in religiously prohibited material, like wine and pigs (Qaraḍāwī 1980: 130–132; Wizārat 1983–2006: 8/129; Mīlād 2004: 185–207, 365).

Classical discussions on the profession of making the to-be-worshipped statues (anṣāb or aṣnām) will be given particular attention here. This is because some recent fatwas made this centuries-old profession analogous to the modern profession of robotics. The focus below will be on specific elements of the discussions on making idols, which were recalled in the discussions on robotics.

One of the core tenets of Islam is monotheism (waḥdāniyya or tawḥīd), which entails belief in God’s oneness and that He has no associates or other gods who would match any of His attributes. This concept has been recurrently stressed and extensively explained in the QuranFootnote 10, SunnaFootnote 11 and related scholarly disciplines, especially Islamic theology (Ghaly 2009a: 4–5; Rāzī 1986a: 312–318). Making idols to be worshipped rather than God or next to God, i.e., idolatry (shirk), which was dominant in the birthplace of Islam, viz., Mecca, has been harshly condemned and ridiculed in the QuranFootnote 12 and judged as categorically prohibited by Muslim scholars. Some scholars went as far as prohibiting making statues almost in toto, including those that represent humans, other living beings or even inanimate objects. This implicates that the very profession of making statues would be forbidden and could not be a source of permissible or pure rizq (Damīrī 2004: 7/383; Ṣaqr 1977: 101; Qaraḍāwī 1980: 131–132)Footnote 13. However, the majority of Muslim scholars adopted a nuanced position, where they usually distinguished between two main categories. The first category, which is prohibited, relates to making statues of “ensouled beings” (dhawāt al-arwāḥ), which comprises human and non-human animals (Mīlād 2004: 301–307). The second category, which is not prohibited but judged as either permitted or reprehensible, relates to making the statues of “non-ensouled beings”, which includes objects like tree, sun, moon, or ship (Mīlād 2004: 315–318)Footnote 14. In their reasoning for the validity of this distinction, Muslim scholars explained that the first category is more likely to be adopted for worshipping purposes and thus its idolatry-related risk is higher. They also added that breathing the soul into human and non-human animals is an exclusively divine act that demonstrates God’s unity. Making statues that externally resemble such ensouled beings is an indication of human arrogance and thus comes close to defying God’s authority. In other words, this act was seen as emulating or mimicking (muḍāhāt) God’s creation of ensouled beings; a divine act that should remain exclusive to God (Mīlād 2004: 312–315, 318–320; Ṣaqr 1977: 101–102)Footnote 15. Based on these lines of reasoning, some scholars argued that using statues for purposes that do not reflect glorification, e.g., objects for children to play with or for educational purposes, will not be judged as prohibited because the idolatry-related risk is quite minimal or non-existing (Mīlād 2004: 310–312; Ṣaqr 1977: 101). Also, some scholars held that making a statue that lacks an essential organ (e.g., head), without which humans or animals cannot survive, would move it to the second category (Shribīnī 1994: 4/409; Mīlād 2004: 304). This is because the risk of mimicking an exclusively divine act, viz., creating ensouled beings, is minimal or completely missing in this case.

It is to be noted here that some religious scholars, especially within the Ḥanafī school, held that making the statues of ensouled beings is just reprehensible and thus would also fall into the second category (Sarakhsī 1993: 1/210–211). Other scholars, including the prominent Shāfiʿī jurist, Abū Saʿīd al-Iṣṭakhrī (d. 940), held that the prohibition of making statues in general is a time-limited and context-specific ruling. According to him, making statues was prohibited during the lifetime of the Prophet of Islam because the risk of idolatry was real and people were still close to the dominant culture of worshipping idols. However, al-Iṣṭakhrī added, this idolatry-related risk has disappeared now and today’s people would naturally avert glorifying statues. This means that the ruling of prohibition does not apply anymore to al-Iṣṭakhrī’s historical context. Had the ruling been perpetual and not time-limited or context-specific, al-Iṣṭakhrī explained, it would have been prohibited to make statues of all what people generally admire and adore, not just those of ensouled beings. He reminded his readers that people in the pre-Islamic period used to worship a wide of range of objects that they admired, including trees and stones (Māwardī 1999: 9/564; Ibn Ḥajar 1959: 1/525; Mīlād 2004: 304–305).

The almost solitary voice of al-Iṣṭakhrī in these pre-modern discussions received support from important contemporary religious scholars. The famous Muslim reformist Muḥammad Rashīd Riḍā (d. 1935) also argued that the prohibition of making statues is contextual and that its main ratio is blocking the means to idolatry. Once the underlying reasons of this prohibition are not present, then making statues should not be judged as prohibited anymore. This was also the practice of influential early Muslim figures, Riḍā explained, including Companions of the Prophet of Islam, when they realized that the idolatry-related risk was not present (Riḍā 1917: 271–273, 276). In response to the controversy around the frieze of the U.S. Supreme Courtroom, which included an image representing the Prophet of Islam, the Azahri scholar, Ṭāhā al-ʿAlwānī (d. 2016) issued a fatwa. Building upon the reasoning provided by Riḍā, ʿAlwānī held that the prohibition of making statues is tied to specific reasons, without which making statues will be permissible. As for the particular case of the frieze, ʿAlwānī even expressed his gratitude and appreciation for those who included an image of the Prophet of Islam in such a highly regarded site (Al-Alwani 2001: 20–22, 25).

2.2.1 Relevance to AI-mediated Work

The abovementioned discussions on making idols resurfaced in the context of discussions related to robotics. Questions were raised, especially by Muslim engineers and roboticists, on whether making humanoid robots can be analogous to making human-like idols and thus would be judged as religiously prohibited. In response, some fatwas published by the famous website Islamweb.net held that the analogy is relevant and thus Muslim engineers should not make robots that assume the shape of ensouled beings, including both humans and animals. Some of these fatwas added that the Prophetic traditions that fore-warned the makers of idols of harsh punishment in the hereafter equally apply to the constructors of humanoid robots. The general advice provided by these fatwas was to avoid constructing robots that resemble any of the ensouled beings. If it was necessary to make such robots, then they should be constructed in a way that would lack some of the essential parts that humans and animals always have, e.g., head (Islamweb 2002, 2003, 2009, 2013).

As is clear from this condensed overview, these fatwas agree on two main premises, namely (a) making statues that assume the shape of humans or animals are prohibited unless they lack an essential part, without which an ensouled being would not survive, and (b) robots are analogous to the statues in this regard. As explained in Sect. 1.2 above, the first premise aligns with the mainstream and nuanced position adopted by pre-modern Muslim jurists.Footnote 16 However, none of the fatwas referred to the other recognized positions in the classical works of Islamic jurisprudence. For instance, no reference was made to the Ḥanafī jurists who held that making human-or animal-like statues is just reprehensible or to the Shāfiʿī jurist, al-Isṭakhrī, who argued that it is permissible. Additionally, no mention was made of the permissive opinions of contemporary scholars like Riḍā and ʿAlwānī. More importantly, the fatwas did not do justice to the rigorous reasoning that Muslim jurists provided to explain the underlying reasons (ʿilla) of prohibiting human- or animal-like statues, especially the idolatry-related risk and the risk of mimicking the exclusively divine act of creating ensouled beings. The fatwas did not inquire whether these reasons are still valid in our modern context, and particularly the context of robotics. For the idolatry-related risk, Muslim-majority countries are replete with statues of prominent national figures. Moreover, many of these countries have specialized colleges and departments, where university students study the art of sculpture and making statues. However, there is no indication whatsoever that Muslims get so infatuated with statues to the extent that one could speak about a phenomenon of Muslims who leave Islam to embrace idolatry. Additionally, making modern statues is usually presented in the context of practicing art rather than promoting theological doctrines and thus it is devoid of the pre-modern Meccan context, which had the outspoken challenge to God’s exclusive authority.

As for the second premise, one would argue that it is even more controversial, and less coherent, than the first premise. The straightforward counterargument to this premise would be that robots and statues belong to two different worlds. This is especially the case when it comes to the fields that they belong to, the purposes for which they are made, the roles they can play in society, in addition to their relevance to the abovementioned two underlying reasons for prohibiting statues. Such differences would make the analogy between the two professions (viz., making human-like statues and humanoid robots) either unconceivable or not solid enough to conclude that both professions are equally prohibited.Footnote 17 Strikingly enough, one of the fatwas issued by the same online portal, Islamweb, stressed that the broad field of AI does not entail any challenges to the belief that God is the sole creator of ensouled beings (Islamweb 2018). Because of its relevance to the question of robots, I want to highlight a point that these fatwas did not pay attention to. Historically speaking, statues are not the closest example to robots because the classical roots of these robots go back to the theory of automata, which were known in the Greek civilization. Automata are pre-programmed machines designed to automatically follow a sequence of operations in accordance with a predetermined set of instructions without human intervention at every step. Making automata thrived in the pre-modern Islamic civilization, thanks to seminal contributions made by engineers and a class of skilled people that can be named as early “technologists”. What is relevant for our discussion here is that some of these automata not only assumed human- and animal shapes but they could also produce human- and animal-like movements and they could utter words (Jazarī 1974, 1979; Banū Mūsa 1979; Hill 1996). Consequently, it is clear that the anti-statues position adopted by the majority of early Muslim jurists did not obstruct the flourishing of (humanoid) automata in the Islamic civilization, although this was the case with making statues.

The example of the prominent Mālikī jurist, Shihāb al-Dīn al-Qarāfī (d. 1285), shows that at least some early Muslim jurists did not draw analogy between statues and automata. Al-Qarāfī upheld the Muslim scholars’ mainstream position towards statues, as outlined in Sect. 1.2 above, which prohibited the statues of ensouled beings (Qarāfī 1994: 13/285–286). However, in one of his works on Islamic legal theory (uṣūl al-fiqh), al-Qarāfī described an automaton that was dedicated to the Sultan which he came to know of. This automaton had a human-like shape that, by the time of the dawn prayer (fajr), would utter the sentence “May God bless the morning of the Sultan with happiness”. Al-Qarāfī himself could construct a similar automaton, with some further enhancements (e.g., adding the shapes of an extra person, a lion and two birds) but he conceded that he could not make the automaton utter that sentence. He also spoke about making another automaton assuming an animal shape that could walk, turn right and left and whistle but, again, he could not make the automaton speak (Qarāfī 1995a, b: 1/441–442).

Although solid conclusions are still in need of thorough review of pre-modern juristic literature, I am not aware of any controversy inside or outside al-Qarafī’s Mālikī school regarding his construction of automata and whether this practice should be as prohibited as making statues. As for the contemporary discussions, the late Syrian scholar ʿAbd al-Fattāḥ Abū Ghudda (d. 1997) commented on what al-Qarāfī wrote and did in this regard by saying that it is indicative of his marvelous intelligence and impressive craftsmanship. As for the possible critique that al-Qarāfī should not have done such automata because they are analogous to statues, which are forbidden in Islam, Abū Ghudda rejected the validity of drawing such analogy. He added that a jurist of the scholarly caliber and moral excellence of al-Qarāfī would have never embarked upon constructing something that is categorically prohibited. Additionally, Abū Ghudda mentioned that al-Qarāfī was not singular in his craftsmanship and that other religious scholars, throughout distant historical periods, mastered similar or even more impressive skills (Qarāfī 1995a: 26–27).

To conclude this section, these robot-fatwas cannot be taken without serious reservations. They are based on two main premises, both of which are quite controversial and in need of critical evaluation. In my opinion, the main problem with these fatwas is the lack of contextual awareness, including both historical shifts and the technical aspects of robotics. Future Islamic ethical discussions on this emerging field should benefit from the accumulated experience of other interdisciplinary fields like Islamic bioethics, especially when it relates to the mechanism of collective reasoning (al-ijtihād al-jamāʿī), where Muslim religious scholars collaborated with specialists in biomedical sciences. To develop Islamic ethical perspectives based on right perceptions and proper understanding of the AI technical aspects, Muslim religious scholas should also collaborate with engineers, computer scientists and specialists in related fields.

2.3 Maintaining Good Relations with Involved Stakeholders

Work agreements and labor contracts initiate a special relationship among the involved stakeholders, which is regulated not only through sets of rights and corresponding obligations but also through associated etiquettes and moral values. Determining what type of work-related juristic and ethical commitments should be in place depends on varied factors, including the moral standing of the respective stakeholders. The abovementioned dichotomy of ensouled vs. non-ensouled beings remains of relevance to this section.

The concept of rūḥ, often accompanied by related terms such nafs (psyche), jism (body) and ʿaql (intellect), has been extensively examined across scholarly disciplines throughout Islamic history (Rāzī 1986b; Ibn al-Qayyim 1996; Makhlūf 1963)Footnote 18. Due to the limited scope of this study, our attention will be solely directed towards the concept of rūḥ, exploring its impact on the categorization of creatures and how this classification further influences work-related relationships. This aspect has predominantly been deliberated within the field of Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh).

As mentioned in Sect. 1.2, the act of creating humans and animals, as beings endowed with souls, is exclusively reserved within the domain of divine agency. The act is regarded as a manifestation of God’s uniqueness, and any attempts by humans to imitate it are strictly prohibited. This theological principle carries significant implications within the discipline of fiqh. Consequently, Muslim jurists have devised the concept of “ḥurmat al-rūḥ (sanctity of the soul)”, which grants both humans and animals, as ensouled beings, distinct entitlements to more dignified treatment compared to other beings. In adherence to this principle, fiqh manuals from different schools devised a broad spectrum of juridical rulings, specifically catering to serve the needs, interests and overall well-being of both humans and animals (ʿAynī 2000: 4/310; Haytamī 1983: 8/373; Bujayrimī 1995: 4/85 Nafrāwī 1995: 1/73)Footnote 19.

Within the broad category of ensouled beings, the focus below will primarily be on human slaves and animals. Unlike free humans, historical ethical discourse have explored the treatment of human slaves and animals as “property” that can be owned but still can be assigned “rights”, some of which resemble those of free humans. In the modern context of AI technologies, the pertinent question arises as to whether AI systems and humanoid robots can be classified within such an intermediate category that was historically assigned to human slaves and animals. It is important to acknowledge that delving into historical discussions on human slaves may evoke sensitivity and even discomfort, given the significant progress made in achieving human consensus on the abolition of slavery. Similar concerns can be raised regarding historical discussions on animals, especially within the modern context of environmental ethics and animal rights. Thus, it is essential to clarify that the discussions and analyses below are not intended to argue for the applicability or relevance of these historical perspectives to our modern societies’ discourse on human rights or animal rights. The sole purpose of examining these historical discussions is to highlight the fundamental role of the concept of rūḥ in the Islamic tradition, particularly for those who contemplate classifying humanoid robots into an intermediate category between humans and inanimate objects, akin to the categorization historically applied to human slaves and animals.

When it comes to the human stakeholders who are involved in a work contract, the main difference between free persons and slaves is that the latter is bound by extra obligations towards his/her master, which put limits on the slave’s scope of authority. To start with, the slave is seen as part of the master’s own property and thus the master is entitled to make the slave part of a purchase contract, lease contract, or to give the slave as a donation (Wizārat 1983–2006: 23/32). With the master’s consent, the slave can engage in agreements on financial transactions or profit-making work with both slaves and free persons, including his/her own master (Wizārat 1983–2006: 23/20–24). As for the revenues of the slave’s work, some Muslim jurists held that they would always be part of the master’s property because the slave is always an owned property and thus would never have the capacity of an owner. Other jurists argued that the slave is in principle entitled to be an owner because of being human (ādamiyya) and being alive (ḥāyāh), and thus can own one’s work revenues as long as the master consents (Ibn 1968: 7/87; Wizārat 1983–2006: 23/39–40). On the other hand, the master has different obligations towards his/her slave, because both the master and slave are God’s servants and the real Owner of all property is eventually God (Wizārat 1983–2006: 23/28). Among these obligations, the master is not allowed to overburden the slave with work beyond his/her capacity and is further prohibited from causing harm to the slave in general (Wizārat 1983–2006: 23/20). The master is also under obligation to provide maintenance (nafaqa) for the slave, spouse and children, even when the slave is unable to work because of temporary or permanent health conditions (Wizārat 1983–2006: 23/25–28).

As for involving animals in labor, Muslim religious scholars put them in a lower category than that of humans, including free persons and slaves, and thus can in principle be used and instrumentalized for the benefit of humans (Ibn ʿAbd al-Salām 1991: 1/6, 68, 74, 102–103; Ibn Khaldūn 1988: 1/120–121; Mūjān 2004: 54–66). Despite this lower rank of moral standing, an animal still enjoys a certain level of dignity or inviolability (ḥurma), because it still remains within the category of ensouled beings. Different juristic rulings translated this abstract concept of ḥurma into practical procedures meant for protecting the animal’s dignity. Different Muslim scholars held that the owner of an animal is under obligation to feed it and to provide it with overall care. Some scholars even argued that the obligation of care towards animals is stronger than the concurrent obligation towards slaves because the latter can complain and express his/her concerns but the former cannot (Ḥaṭṭāb 1992: 4/207). Also, unauthorized aggression against the animal’s life, including certain scenarios within the context of war, would entail disciplinary procedures for the human aggressor (Rūyānī 2009: 4/36; Ibn 1968: 9/289–290; Wizārat 1983–2006: 2/126; Mūjān 2004: 352–353). As for the context of work and financial transactions, an endowment can be dedicated for animal welfare (Mūjān 2004: 681–683). Finally, animals in principle fall within the category of properties that have commercial value (māl mutaqawwam) and thus can be the subject of a wide range of financial contracts, including purchase, lease, donation, and pledged property (rahn) (Wizārat 1983–2006: 36/34; Mūjān 2004: 141, 301–573, 687–701).

2.3.1 Relevance to AI-mediated work

As outlined above, the moral standing of the involved stakeholders in work relationship is crucial in the Islamic tradition for determining how far this relationship would entail obligations, rights and etiquettes. The secular discourse on AI ethics has provided intensive discussions that touched upon the moral standing of AI systems or robots in particular, and whether they will be entitled to rights similar or close to those of human slaves or animals (Bryson 2010; Gunkel 2018; Danaher 2019; Crawford 2021).Footnote 20

Based on the discussions outlined in the previous section, one can safely argue that AI-systems, including humanoid robots, cannot fall within the above-outlined intermediate category that was historically assigned to human slaves and animals. Without delving into the discussions about the possibility that (future) AI systems would have conscience, sentience or self-awareness, no claim can be made that they have souls and would thus be entitled to the rights emanating from the concept of “ḥurmat al-rūḥ (sanctity of the soul)”.Footnote 21

As explained above, slaves are viewed as humans who have human dignity, despite the limited scope of their autonomy because they are considered as part of their owners’ property. Also, animals fall within the category of ensouled beings and thus enjoy that soul-related dignity, even if they are classified in a lower category than that of humans. Humans who mistreat an animal will be, religiously speaking, judged as sinful in front of God and can also be liable to disciplinary procedures imposed by the judge or the state. To the best of my knowledge, no authoritative opinion among early or modern Muslim religious scholars ever defended the thesis that any other being or object, beyond humans and animals, would fall into the category of ensouled beings. This applies to the items that used to play a significant role in work agreements or profit-making transactions, e.g., houses, ships, agricultural tools, minerals, etc. If we take Muslim scholars’ discussions on work agreements related to cultivating land as an example, one sees scenarios where a free human, a slave, an animal and an agricultural tool like the plow can all be involved. Scholars would generally tolerate the possibility that the tool would play the most important role in getting a specific work done and thus can be the most expensive part of the work agreement. However, this would not make Muslim scholars assign the tool a moral standing, which is higher than, or even equal to, that of an animal or slave. (Mawwāq n.d.: 7/30).

Besides the literature produced by religious scholars, the celebrated work written by the Muslim engineer, Badīʿ al-Zamān al-Jazarī (d. 1206), also consolidates the thesis that humanoid robots do not fall within the category of ensouled beings. Al-Jazarī’s work was on automata that we discussed in the previous section (1.2.1), The automata described in al-Jazarī’s work included various examples that not only assumed the shape of humans (humanoid automata) and animals but also could produce movements (ḥarakāt) close to those made by ensouled beings (mushabbaha bi al-rūḥāniyya) (Jazarī 1979: 3).Footnote 22 However, al-Jazarī did not indicate that such automata can be classified as humans or animals. Although he would use words like girl, boy, man, elephant, and peacock to indicate the shape that the respective automaton would assume, al-Jazarī always referred to these automata by using terminology, which is specific to inanimate objects, e.g., ālah (tool, instrument, device or machine) and shakl (shape, model or construction) (Jazarī 1979: 576, 581).

It is true that modern AI-enabled humanoid robots, unlike al-Jazarī’s automata, have “artificial intelligence” and thus are designed to “think” and make decisions. However, these extra features will not justify classifying these robots within the category of ensouled beings. One of the agreed-upon positions among Muslim religious scholars is that ensoulment is a metaphysical concept and an exclusively divine act, which falls beyond the scope of human agency. In his renowned work dedicated to the concept of rūḥ, the Ḥanbalī theologian and jurist Ibn al-Qayyim (d. 1328) provided a comprehensive examination of the different perspectives held by Muslim theologians and philosophers regarding this concept. He asserted that the correct understanding of rūḥ, substantiated by abundant evidence from the Quran, Sunna, consensus of the Prophet’s Companions, and rational reasoning, is that it is a distinct entity whose nature differs from the physical body. He further elaborated that rūḥ is a light-filled, celestial, subtle, animate, and mobile body that permeates the very essence of the organs and flows within them, akin to water flowing in a rose, oil flowing in olives, and fire burning within charcoal. Emphasizing the inherent connection between possessing a soul and having the distinctive characteristics of being alive, he added that as long as these physical organs are receptive to the influences emanating from the soul, they experience sensations and produce voluntary movements. Upon departure from the physical body and the dysfunctionality of the organs, the soul leaves the physical world to join the metaphysical and spiritual one (Ibn al-Qayyim 1996: 256–257).Footnote 23 In the context of work and labor, AI systems, including humanoid robots, will thus remain within the category of non-ensouled beings, more specifically the tools which have commercial value (māl mutaqawwam). As a result, there is no inherent problem in including them in work agreements and assigning them a financial value that can be purchased, leased, borrowed, gifted, etc. However, by not classifying these smart tools as ensouled beings, they cannot be held liable for errors that caused material damage or financial losses for the other involved stakeholders. This is because they are not human. Also, the other stakeholders will not be under obligation to respect their dignity (ḥurma) because they are not animals.

On the other hand, it is important to emphasise that many of the objects categorized as non-ensouled beings can hold moral significance from an Islamic perspective, and that their value is not solely determined by their market price. The overall value of such objects is usually tied to their benefit (manfaʿa), which can assume non-financial forms. A notable example is the work of al-Jazarī who manufactured automata designed to serve a religious purpose, such as automating the ritual of ablution (wuḍūʾ) (Jazarī 1979: 323–344). Muslim philosophers have also written about the idea that humans can feel so attached to non-human creatures, including inanimate objects like tree, mosque or a specific place therein, leading to a special companionability (ilf) and amicability (uns) between the two (Tawḥīdī and Miskawayh 2017: 108–109). The discussions of Muslim jurists in the Shāfiʿī school regarding condolences (taʿyiza) are relevant to this kind of companionability with non-ensouled beings. They held that it is recommended to offer condolences to anyone who experienced a significant loss, whether it involves losing ensouled or non-ensouled beings (Ramlī 1984: 3/13; Bujayrimī 1995: 2/306–307).

Recognizing the wide range of benefits that modern robots can provide, from treating diseases up to the military service of defending one’s country against enemies, would also add to their overall value. Additionally, every Muslim individual is required to develop a virtuous character to maximize one’s good acts and minimize the bad ones, irrespective of the nature of the creature that one is dealing with, including both ensouled and non-ensouled beings. With regards to the scope of moral excellence (iḥsān), the Prophet of Islam stressed that it encompasses “ all things”Footnote 24. By extension, a virtuous person should also be virtuous in dealing with robots, not because robots have inherent dignity similar to those of ensouled beings but because of one’s quest to be virtuous.

3 Concluding Remarks

The emerging field of AI ethics, along with its sub-field of AI-mediated work ethics, has been predominantly secular, with limited contributions from religious traditions, including world religions like Islam, Christianity and Judaism. However, the breadth and depth of ethical challenges posed by advancing AI technologies require a diverse ethical discourse that reflects the diversity of people’s moral worlds, including those shaped by religious beliefs and value systems. In this article, we tried to show how Islamic perspectives would contribute to the discourse examining the ethics of AI-mediated work. Specifically, we focused on three key components of the moral world of work in the Islamic tradition and examined how they relate to the modern context of AI-mediated work.

Regarding the first component, we explained the widely accepted position among different Islamic scholarly disciplines holding that work has inherent value for humans. Besides meeting material needs and generating financial profits, work also entails theological, philosophical, juristic and spiritual benefits. That is why, we argued, it is not good to keep the excessive increase in work automation or robotization, where smart machines would replace human labor, and humans would solely reap the benefits of these machines’ work. Nevertheless, we have shown that a minority position, particularly within Sufism, held that engagement in work and labour is either not good or at least morally inferior to the cultivation of spiritual virtues, such as reliance on God, abstinence and detachment from worldly life. Thus, an important question for future exploration is whether the AI technologies will disrupt the long-standing position about the inherent value of work and give more prominent and appeal to these Sufi perspectives.

In relation to the second component, we explained the consensus among Muslim scholars that one should only engage in work or profession, which is religiously permissible (ḥalāl). We examined recent fatwas that drew analogy between the historically prohibited profession of making human-like statues and modern humanoid robots. This perspective was critically analyzed by highlighting the crucial differences between the two. Instead, we proposed a more suitable analogy with the historical profession of making automata, the classical roots of modern robotics, which thrived in the Islamic civilization despite the then prevailing opposition to making statues. Nonetheless, the increasing interest in making AI systems and humanoid robots that may not resemble humans externally but get mimic human cognition, will pose new challenges. Therefore, another question requiring further exploration in advancements in this direction will amplify religious concerns about the profession of creating humanoid robots that will increasingly resemble humans in both appearance and cognitive abilities.

In exploring the third component, we examined how the moral standing of stakeholders involved in work relationships would affect the set of mutual rights, obligations and associated etiquettes. Muslim scholars generally categorize all creatures into two broad groups, namely ensouled beings, comprising humans and animals and non-ensouled beings, encompassing inanimate objects and other creatures. We also considered the possibly intermediate category that was historically assigned to human slaves and animals, where they both could be “owned” but still possessed rights emanating from the concept of the dignity of soul (ḥurmat al-rūḥ). We conclude that AI-systems and robots can only be classified as non-ensouled beings and thus cannot be assigned the set of rights and obligations emanating from the concept of ḥurmat al-rūḥ. However, the material and non-material benefits accruing from the AI technologies will inevitably disrupt this long-standing dual classification. While we do not anticipate serious claims advocating for robots to be considered ensouled beings, there is a need for more nuanced sub-categorization within the group of non-ensouled beings, enabling AI systems to be better situated among the stakeholders involved in work relationships or within society at large. Drawing upon classical discussions in Islamic philosophy and jurisprudence, we argue that human-robot relations can be better regulated at the hand of moral obligations stemming from one’s relationship with God, with human owners of these robots and from one’s own virtuous character. Future research should delve into more detailed questions in this regard as well.

Notes

The GCC is a regional union established in 1981, currently comprising six countries in the Gulf region, viz., Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates. https://www.gcc-sg.org/en-us/AboutGCC/MemberStates/pages/Home.aspx (accessed 26 September 2022).

https://sdaia.gov.sa (accessed 27 August 2022).

The other five principles are Race for Talent in the “AI + X” Era, Data Access is Paramount, the Changing Landscape of Employment, New Business and Economic Opportunities, and the AI + X Nation (QCRI 2019: 8–14).

Further examination of these minority views will be elucidated below, as part of discussing the discipline of Sufism. The intricacies associated with pro-work and anti-work perspectives do not necessarily stem from disagreements within Islamic theology but mainly from the variations between Sufi perspectives and those developed in other scholarly disciplines.

The critique from outside the discipline of Sufism was sometimes harsh. For instance, the Ḥanafī jurist Muḥammad b. al-Ḥasan al-Shaybānī (d. 805) described the advocates of the position that work is sinful as “A group of the ignorant ascetics and foolish Sufis” (Shaybānī 1980: 37).

The list of Quranic verses provided by al-Muḥāsibī included the following: “O believers! Spend from the best of what you have earned” (02: 267), “O believers! When you contract a loan for a fixed period of time, commit it to writing” (02:282), and “O believers! Do not devour one another’s wealth illegally, but rather trade by mutual consent” (04:92) (Muḥāsibī 1992: 42).

The Prophetic tradition that was central in al-Muḥāsibī’s scriptural reasoning reads “The best (afḍal) or most pure (aṭyab) food that a man eats is that which he has earned himself” (Muḥāsibī 1992: 24, 25, 38, 43–44).

Besides humans, Muslim religious scholars generally accept that idea that taklīf applies for the jinn and angels as well (Zarkashī 1994: 2/56). For our human world, however, both the jinn and angels make part of the invisible world (ghayb). Further, I am not aware of any voices, inside or outside the Islamic tradition, arguing that robots can be analogous to the jinn or angels, especially in the context of work.

Examples of Quranic verses include “And your God is One God; there is no god but He, the Most Compassionate, Most Merciful” (02:163); “There is nothing like Him, for He [alone] is the All-Hearing, All-Seeing.” (42:11).

One of the key Prophetic traditions in this regard relates that the Prophet of Islam said to His Companion Muʿādh, “Do you know what is the right of God upon His servants, and what is the Right of His servants upon God?” Muʿādh said: “God and His Messenger know better.” Upon this, the Prophet said, “God’s right upon His servants is that they should worship Him alone and associate nothing with Him; and His servants’ right upon Him is that He should not punish who does not associate a thing with Him” (Ibn Ḥajar 1959: 13/355).

Examples of Quranic verses include “Indeed, Allah does not forgive associating others with Him” (04:48); “So proclaim openly what you have been commanded and ignore the idolaters” (15:94); “He argued, “How can you worship what you carve [with your own hands], although it is Allah Who created you and whatever you do?” (37:95–96); “Indeed, true devotion is due to God alone. As for those who take other lords besides Him, saying, ‘We worship them only so they may bring us closer to God,’ surely God will judge between all regarding what they differed about. God certainly does not guide whoever persists in lying and disbelief.” (39:03).

Some contemporary scholars extended the scope of this ruling to include the prohibition for Muslim countries to establish museums comprising statues of previous non-Muslim figures or to collect money by imposing entrance fees for such museums (Subayʿī 2014: 384, 386–387).

The Islamic tradition has a standard fivefold scheme for the classification of human acts. So, each action would normally fall into one of five main categories, namely obligatory (wājib), forbidden (ḥarām), recommended (mandūb), reprehensible (makrūh) or permissible (mubāḥ). The (non-)conformity of one’s act with God’s will plays a key role in judging the moral worth of such act and thus will be categorized within one of these categories accordingly. For instance, the category of prohibited acts will include those acts whose commission would incur God’s wrath and punishment in this life or in the hereafter. However, the category of reprehensible acts would include those acts that are discouraged from a religio- ethical perspective although they are not strictly forbidden (Ghaly et al. 2016: 37–39).

Muslim scholars usually refer in this context to the Prophetic tradition, which states that God would summon the makers of such statues on the Day of Resurrection and challenge them by saying “Make alive what you have created!”. Scholars argue that “Making alive” here refers to the act of breathing the soul, which is the source of human life (Mīlād 2004: 308). The most comprehensive list of the Prophetic traditions with relevance to this discussion was provided by Rashīd Riḍā (Riḍā 1917: 221–226).

In a pioneer study which reviewed some of the fatwas issued on robotics and AI, it was stated that the second premise was adopted because the fatwa-issuing website, viz., Islamweb, follows a Wahhabi-conservative and strict interpretation of the religious sources of Islam. Considering the specific focus of this study, it did not further investigate this issue in the classical works of Islamic jurisprudence to demonstrate or explain the conservativeness of this premise, compared to the other positions adopted by earlier Muslim jurists (Singer 2021: 283, 284, 289, 291).

Considering the focus of this study and that the primarily targeted audience are not necessarily specialists in Islamic studies, I did not get into in-depth discussions about analogy (qiyās) as a technical concept in Islamic legal theory (uṣūl al-fiqh). One of my future studies will hopefully focus on these aspects to analyze the pros and cons of the analogy made by these fatwas, from an uṣūlī perspective.

As shown in these quoted sources, the examination of similarities, distinctions, and subtleties among these concepts has been the subject of centuries-old extensive discussions and controversies. Various perspectives have emerged, with some arguing that rūḥ and nafs are identitcal and thus the two terms can be used interchangeably, whereas others held that nafs is the rūḥ when it gets united with the physical body, and so on. Delving into these intricate debates is beyond the scope of this study and thus the focus here will be on the moral significance of the concept of rūḥ and its juristic implications in the domain of work relations.

The quoted fiqh manuals include various examples that illustrate the juristic implications of ḥurmat al-rūḥ. One such example pertains to a scenario where a ship involved in skinning requires throwing some items into the sea in order to save it. In such a situation, the principle dictates that non-ensouled beings, including valuable goods, should be sacrificed first. Because of the sanctity of their souls, animals and humans should be granted greater protection, where animals are only secondarily to humans.

While this article focuses on Islamic perspectives, a brief note is due to clarify Dr. Joanna Bryson’s standpoint, as outlined in her extensively cited work “Robots should be slaves.” Despite using the term “slaves” in the title, Bryson clearly indicated that her aim was to argue that robots should be treated as objects or tools to which humans would have no moral obligations, and thus robots should not even be human-like because they will inevitably be owned by humans (Bryson 2015). Bryson’s perspective aligns with previous authors who discussed the concept of “machine slavery” although they explicitly condemned “human slavery” (Wilde 1891; Benjamin 2016). To my knowledge, there are no previous authors in the field of Islamic Studies who have adopted this distinction between “human” and “machine” slavery. As explained in this article, the dominant categorization throughout the history of Islamic scholarship is to divide creatures into (a) ensouled beings, comprising humans and animals, and (b) non-ensouled beings, including inanimate objects (jamādāt) and the rest of creatures. Although plants are usually classified in the (b) category, some scholars proposed putting them in a distinct category, because they have vegetative life but no soul (Ruʿaynī 1992: 1/89).

While the category of non-ensouled beings would usually include inanimate objects (jamādāt) and all other creatures apart from humans and animals, some scholars have proposed a distinct category for plants. The alternative triple categorization would consist of (a) ensouled beings, encompassing humans and animals, (b) plants, and (c) non-ensouled beings, which would include all other creatures (Ruʿaynī 1992: 1/89). To my mind, the alternative triple categorization will have no significant implications for the discussions on the moral standing of AI systems and humanoid robots. Furthermore, I am unaware of any researchers who argue for equating AI systems and plants regarding their moral standing.

This is my own reading of al-Jazarī’s original text in Arabic. It is to be noted in this regard that the art of manufacturing such automata was sometimes called the “science of spiritual tools” (ʿilm al-ālāt al-rūḥāniyya) and al-Jazarī’s book was sometimes known by the title of Al-Ālāt al-rūḥāniyya (spiritual tools). According to the famous Ottoman bibliographer, Ḥājjī Khalīfa (d. 1657), the link between this art and the term “spiritual tools” is that the automata can entertain one’s spirit/soul or psyche (Ḥājjī Khalīfa 1941: 1/148, 255, 2/1395). My interpretation of al-Jazarī’s text and Khalīfa’s note can be combined by arguing that such automata could entertain and startle human souls because they looked like humans, especially in the outer shape and the seemingly autonomous behavior.

The Prophetic tradition states “God has prescribed moral excellence (iḥsān) on everything” (Muslim n.d., 3/1548).

References

ʿAbd al-Jabbār. 1963. Al-Mughnī fī abwāb al-ʿadl wa al-tawḥīd Cairo: Al-Muʾassasa al-Miṣriyya al-ʿĀmma li al-Taʾlīf wa al-Tarjama wa al-Ṭibāʿa wa al-Nashr.

ʿAbd al-Jabbār. 1996. Sharḥ al-usūl al-khamsa. Cairo: Maktabat Wahba.

Al-Alwani, T. 2001. Fatwa concerning the United States Supreme courtroom frieze. Journal of Law and Religion 15: 1–28.

Al-Ḥakīm al-Tirmidhī. 1976. Ādāb al-murīdīn wa bayān al-kasb. Maṭbaʿat al-Saʿāda.

Ansari, Z. 1969. Taftazānī’s views on Taklīf, Ğabr, and Qadar: a note on the development of Islamic theology. Arabica 16(1): 65–78.

Ashʿarī, A., and al-. 2005. Maqālāt al-Islāmiyyīn wa ikhtilāf al-muṣallīn. Al-Maktaba al-ʿAṣriyya.

ʿAynī, B. al-. 2000. Al-Bidāyah sharḥ al-Hidāyah. Dār al-Kutub al-ʿIlmiyya.

Azar, E., and N. Haddad. eds. 2021. Artificial intelligence in the Gulf: Challenges and opportunities. Springer.

Banū, Mūsa. 1979. The Book of ingenious devices (Kitāb al-ḥiyal). Translated by Donald Hill. D. Reidel Publishing Company.

Benjamin, R. 2016. Catching our breath: Critical race STS and the carceral imagination. Engaging Science Technology and Society 2(0): 145–156.

Black, A. 2011. The history of Islamic political thought: From the Prophet to the present. Edinburgh University Press.

Brynjolfsson, E., and A. McAfee. 2014. The second machine age: Work, progress, and prosperity in a time of brilliant technologies. WW Norton & Company.

Bryson, J. 2010. Robots should be slaves. In Close engagements with artificial companions: Key social, psychological, ethical and design issues, ed. Y. Wilks, 63–74. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Bryson, J. 2015. Clones should NOT be slaves. An online article published on 04-10-2015. It can be accessed via https://joanna-bryson.blogspot.com/2015/10/clones-should-not-be-slaves.html (accessed 20 May 2023).

Bujayrimī, al-. 1995. Tuḥfat al-ḥabīb ʿalā sharḥ al-Khaṭīb, Dār al-Fikr.

Crawford, K. 2021. The atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Damīrī, K. al-. 2004. Al-Najm al-wahhāj fī sharḥ al-minhāj. Jeddah: Dār al-Mihāj.

Danaher, J. 2019. Welcoming robots into the moral circle: A Defence of ethical behaviourism. Science and Engineering Ethics 26: 2023–2049.

Dhawdī, M. al-. 2000. Al-Dhakāʾ al-insānī wa al-iṣṭināʿī fī ḍawʾ al-Qurʾān al-Karīm. Muntadā al-Lalima li al-Dirāsāt wa al-Abḥāt 7 (26): 64–77.

El Sherif, A. 2020. Dubai Health Authority deploys robots to disinfect facilities. Available at https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/emea/dubai-health-authority-deploys-robots-disinfect-facilities (accessed 27 September 2022).

Fakhry, M. 1991. Ethical theories in Islam. Brill.

Farābī, al-. 1985. Fuṣūl muntazaʿa. Iran: Al-Maktaba al-Zahrāʾ.

Farābī, al-. 1995. Arāʾ ahl al-madīna al-fāḍila wa muḍāddatuhā. Dār wa Maktabal al-Hilāl.