Abstract

This paper aims to square our considered judgements about the moral significance of healthcare with various empirical and conceptual challenges about its role in a theory of justice. I do so by defending the moral significance of healthcare by reference to a central but neglected dimension – healthcare’s expressive function. Over and above its influence on health outcomes and other metrics of justice (such as opportunity or welfare), and despite its relatively limited impact on population health outcomes, healthcare expresses respect for individuals in a distinctive and morally salient way. Grounding the moral significance of healthcare in this way not only highlights an important distinguishing feature of healthcare, but it also makes our support for healthcare immune from several powerful objections against its significance. This conclusion has important implications for theorists of (health) justice and for political philosophers more widely, highlighting the appropriate role of healthcare within public policy and normative theorising about theories of justice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: What Is the Point of Healthcare?

Health and healthcare are contested concepts subject to much debate over their definitions, scope, and relative importance compared to other goods. One important point of contention is the role (if any) of healthcare within the pursuit of health or justice more broadly, given various empirical and conceptual challenges against its significance. The challenge is to articulate the moral significance of healthcare (the practice of providing clinical care by health professionals) as opposed to the broader notion of health (a state of the absence of disease) and non-clinical interventions (such as public health initiatives or action aimed at the social determinants of health). By moral significance, I simply mean the fact of something possessing normatively salient features such that it warrants inclusion as a central component of justice.

This paper aims to square our considered judgements about the moral significance of healthcare with various empirical and conceptual challenges about its role in a theory of justice.Footnote 1 I do so by defending the moral significance of healthcare by reference to a central but neglected dimension – healthcare’s expressive function. Over and above its influence on health outcomes and other metrics of justice (such as opportunity or welfare), and despite its relatively limited impact on population health outcomes, healthcare expresses respect for individuals in a distinctive and morally salient way. Grounding the moral significance of healthcare in this way not only highlights an important distinguishing feature of healthcare, but it also makes our support for healthcare immune from several powerful objections against its significance.

The philosophical implications of this paper are not merely theoretical. The moral significance of healthcare determines the contours of the state’s duty to provide healthcare services, including the stringency and content of this obligation. As we shall see, if healthcare is merely intended to promote health, then the empirical evidence seems to suggest – perhaps counterintuitively to many – that we are better off taking money away from the healthcare budget and diverting these towards non-healthcare interventions to improve the social conditions in which people live.Footnote 2 Accordingly, a health-based argument for healthcare may have the effect of undermining state policies intended to provide universal healthcare. If we can establish that healthcare is a good with high moral significance – as I shall argue – then the state’s duty to provide this good and ensure equitable access to it is made stronger. The provision of healthcare, as a matter of justice, may then have increased priority or stringency compared to (for example) ensuring citizens’ access to cars or computers. This paper presents an original argument for how we might think about the moral significance of healthcare and, in doing so, highlights the contours of the state’s obligations of justice with regard to the provision of this good.Footnote 3

By healthcare, I mean treatment and care provided by clinical professionals (doctors, nurses, pharmacists, paramedics, and other allied health professionals) for the purpose of alleviating disease and promoting our health. Following Norman Daniels and Christopher Boorse, we can define health as a state of normal species functioning (defined by reference to the bio-statistical norm for the class) and most notably the absence of pathology (Boorse 1977; Daniels 2007). This is not an uncontroversial definition of health, as debates in the bioethics and philosophy of medicine literature highlight (Kingma 2010a, b, 2007; Go 2018; Hausman 2006). I have included this definition – despite my personal disagreement with it – for prudential reasons, namely, due to its significant influence in the philosophy of health and political theory literature, and because it strikes a middle ground between the overly expansive definition of the World Health Organization (WHO) where health is ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’ and the more minimalist, physicalist definition championed by Dan Callahan, where health merely concerns the absence of physical but not mental illness (WHO 1946; Callahan 1973). Ultimately, however, my account of healthcare’s expressive function is compatible with a wide range of other accounts of health, and not much turns on this definition. Individual health concerns the health status of a particular individual, while population health concerns the aggregate level of health in the population as well as the distributive pattern of health within a population.Footnote 4

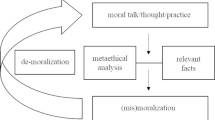

My strategy in this paper unfolds as follows. In the first section, I analyse the so-called specialness of healthcare thesis, presenting two core reasons proponents advance in support: the Health View and the Justice View. I present several objections to these views – the relative insignificance objection, the undue narrowness objection, and the circumvention objection – which I argue undermine the plausibility of these views for grounding the moral significance of healthcare. In the second section, I argue that a central (though not exclusive) feature of healthcare which explains its moral significance is its expressive function. That is, its ability to express respect to individuals in a morally significant and salient way in light of our status as inherently vulnerable individuals. In the third section, I explore several objections to my account, including general scepticism about the significance of respect and the expressive function and whether this is sufficiently strong to justify state policies; concerns about my account being too broad or too narrow; concerns that my account may be self-defeating; and worries about paternalism.

2 The Specialness of Healthcare Thesis

Most of us value healthcare and regard it as an important aspect of egalitarian justice. The idea that healthcare is somehow special is an intuitive one, with many people supporting the view that healthcare should be universally accessible and distributed independently of people’s ability to pay. For many, inequalities in access to healthcare are often viewed as more troubling than inequalities in other domains, such as in income or education. The idea that healthcare has special moral significance and should be a central concern of justice has been referred to as the specialness thesis.Footnote 5 The specialness thesis is generally premised on one of two somewhat interrelated reasons: first, that healthcare is special because of the way it contributes to health (which proponents regard as intrinsically valuable) or second, that healthcare is special because of the way it contributes to health which in turn contributes to some other ultimate goal of justice (such as opportunity, welfare, or capabilities).

The language of specialness is widely used in the literature, in a large part due to its foremost proponent, Norman Daniels. However, it is much more fruitful, in my view, to analyse what makes healthcare ‘morally significant’ (a question that invites a potentially complex, non-binary answer) rather than whether healthcare is ‘special’ (a question that invites a binary answer and one which can isolate those already tired of this debate).Footnote 6 In the remainder of the paper, then, my focus is not whether healthcare is special, but whether it is morally significant and, if so, in what ways. That is, what features about healthcare warrant its inclusion at the bar of justice. In the language of moral significance rather than specialness, the aforementioned reasons can be phrased as follows:

HC 1 (Health View)

The moral significance of healthcare lies in its ability to promote health – to alleviate, manage, and/or minimise illness and disease.Footnote 7

HC 2 (Justice View)

The moral significance of healthcare lies in its ability to promote some broader metric of justice (such as wellbeing or opportunity) because of the link between health and that broader metric of justice.

On the Health View in HC1, health is treated as something intrinsically valuable and the ultimate end of healthcare. Healthcare serves the function of promoting health through mitigating or curing disease and managing chronic conditions. This seems to align with most laypeople’s intuitive view about the function of healthcare, whereby we go to the doctor to get treated and have our health restored. It is also the dominant language of those involved in health activism. Proponents of universal healthcare, for example, support such a policy on the grounds that it would ensure everyone can be healthy, rather than limiting this privilege only to those who can pay for their own healthcare. The Justice View in HC2 takes the form of a two-step justification. In HC2, healthcare promotes health (as in HC1) and this is important because of health’s central contribution to justice in the form of promoting opportunity, welfare or capabilities. In HC1, health is treated as intrinsically valuable, while in HC2, health is treated as instrumentally valuable for a further good that is the subject of justice. Norman Daniels is the foremost defender of HC2, arguing that healthcare is morally significant because of the way it promotes health, which in turn promotes fair equality of opportunity (Daniels 1985, 2007).Footnote 8 For Daniels, healthcare is morally significant because of the way it realises fair equality of opportunity, which is a fundamental demand of justice.

Some important conceptual clarifications are required at the outset. First, despite my statements about the centrality of healthcare to most conceptions of egalitarian justice, my primary analysis in this paper is about whether healthcare promotes health, broadly conceived, rather than whether healthcare can equalise it. The promotion of health is, in many ways, prior to the question of equalising health. This is because unless we want to level down health – something most would regard as implausible, especially with regards to health – then we need to first work out if healthcare can promote health before deciding if we want to use it to achieve the ends of egalitarianism (and if so, how).Footnote 9

Second, HC1 and HC2 may be phrased in strong and moderate variants. On the strong variant, the moral significance of healthcare lies solely in its ability to attain the respective ideal (i.e., solely for the promotion of health in HC1 or solely for the pursuit of other metrics of justice in HC2). On the moderate variant, the moral significance of health lies primarily (though not solely) in its ability to attain the respective ideal. Third, HC1 and HC2 are not necessarily mutually exclusive. The moral significance of healthcare may simultaneously lie in its ability to alleviate disease (recognising the intrinsic value of health) and to promote opportunity. Because of this conceptual relationship, my constructive argument engages simultaneously with HC1 and HC2, and with both its strong and moderate variants. These conceptual distinctions do not substantively challenge my forthcoming critical and constructive arguments.

Despite their initial plausibility in justifying the supposed point of healthcare, neither HC1 nor HC2 can establish the moral significance of healthcare in a sufficiently robust manner. In the case of HC1, decades of empirical evidence around the social determinants of health and the literature detailing the influence of non-clinical public health initiatives refute the idea that healthcare is the primary determinant of population health outcomes (Marmot and Wilkinson 2006; CSDH and Marmot 2008).Footnote 10 The social determinants of health (including housing, class, working conditions, education, social capital, as well as broader conditions such as the political, structural, and welfare and economic policies of the society) and non-healthcare-based public health initiatives (such as nutrition and sanitation) have a much greater impact on population health outcomes than healthcare. The WHO estimates that the social determinants of health are responsible for up to 55% of population health outcomes, while one study showed that access to health coverage (including through insurance) reduced the likelihood of poor health by only 10% (WHO 2021; Barker and Li 2020). An OECD report shows that universal healthcare is associated with around a 1-year increase in life expectancy, but that education, high income, environmental air quality, and healthy environments contributed 3.75 years more (OECD 2016, 6).

Non-healthcare public health initiatives, most notably in the area of improved nutrition and sanitation, are widely regarded as having a relatively greater impact on population health outcomes than healthcare. Historians of health argue that it was improved nutrition and sanitation, not healthcare advances, that was the primary contributor to increased life expectancy over the past few centuries (Fogel 1986). More recent evidence on the effects of nutrition and environmental health initiatives also supports the view about the relatively greater impact of non-clinical public health interventions on population health outcomes compared with healthcare (Strulik and Vollmer 2013; Rahman, Rana, and Khanam 2022).

These findings have been traced to the fact that it is the social determinants of health and non-healthcare public health-based interventions (especially in nutrition and sanitation) that are the primary influence on population health outcomes and not healthcare, universal or otherwise. Healthcare is, metaphorically speaking, merely the ‘ambulance at the bottom of the cliff’. Its influence on health is much less than commonly assumed. Call this the relative insignificance objection.

If we really cared about promoting better, more equitable population health outcomes, we would focus on non-healthcare-based interventions at the level of social policy. Not only would such interventions have a statistically greater impact in improving overall health outcomes, but they would also reduce the incidence of people falling ill and requiring the healthcare system in the first place. In fact, Gopal Sreenivasan argues that there may be a strong case at the bar of justice to reallocate the entire healthcare budget towards non-healthcare interventions that focus instead on the social determinants of health (Sreenivasan 2007).Footnote 11 As a striking example, the United States spends more on publicly-funded healthcare per capita than most developed countries, but is regularly at the very bottom in rankings of overall health outcomes (Schneider et al. 2021). Most disturbing to many egalitarian theorists is the fact that population health outcomes have not improved for the poorest and most disadvantaged groups even with the introduction of universal healthcare. Two influential reports published in the UK – the Black Report and the Acheson Report – showed that since the creation of the National Health Service, population health outcomes among the most disadvantaged have not improved and, in many cases, health inequalities in society have actually widened (Black et al. 1982; Acheson 1998).

There is, of course, the question of the right counterfactual to use. Even if universal healthcare has not improved population health outcomes, it might be that they would have been worse without universal healthcare. From the fact that population health outcomes did not improve much with universal healthcare, we cannot infer that health outcomes would not have gotten worse without it. Even if it were true that health outcomes would have been relatively worse without universal healthcare, the overwhelming evidence still shows that the social determinants of health are greater in their influence on health outcomes regardless of how much healthcare we provide to all.

To be clear, the claim is not that healthcare does not improve population health. Rather, it is that the impact of healthcare is much less than commonly thought and relatively small when compared to non-healthcare public health initiatives and interventions targeting the social determinants of health. Given competing priorities for the national budget and the distributive implications of moderate scarcity and given that there are competing priorities for the budget and a desire to make health policy as effective as possible, policymakers and theorists of justice who defend healthcare on grounds that it promotes health are faced with the relative insignificance objection. Arguing for the moral significance of healthcare solely or primarily on the grounds that it promotes population health (HC1) is empirically questionable and thus ultimately unsuccessful.Footnote 12

In the case of HC2 (the Justice View), two additional objections can be marshalled. First, as Shlomi Segall and others have pointed out, justifying the moral importance of healthcare on the grounds of promoting opportunity – one version of the HC2 view – risks making it too narrow and failing to justify healthcare in situations when we think it is called for (Segall 2007, 2010). Healthcare treatment for mild eczema or asthma, for example, may not be justified on opportunity grounds because these conditions do not curtail one’s opportunity range or affect equality of opportunity in any meaningful way. Call this the undue narrowness objection. Second, and moving beyond the opportunity conception of HC2 it is not clear that healthcare is always an effective way of promoting the ultimate goal of justice we are aiming towards, whether this is opportunity, welfare, or some other metric. It is possible that welfare or opportunity can be promoted in more direct ways, by circumventing healthcare and therefore denying it a distinctive role. Consider, for example, an HC2 view grounded in welfare. If what we ultimately care about is welfare rather than health (unlike in HC1), then it is always possible to just bypass healthcare and do something else to promote welfare directly. To give just some rough examples, many people get more welfare from money and luxurious holidays than they do from receiving healthcare or from the health that healthcare (let us grant) supposedly secures. If welfare is the ultimate goal of justice and healthcare is merely a way to get there, then there would be nothing wrong with the state diverting resources from healthcare to promote welfare in more direct and effective ways.Footnote 13 Call this the circumvention objection.

One immediate suggestion is that we should distinguish between objective and subjective conceptions of welfare. The person who desires the luxurious holiday over receiving vital healthcare might simply be mistaken about what would promote her welfare, and this is something an objective theory of welfare can correct. While objective theories of welfare such as an objective list theory that included health status among its metric may ameliorate the force of the circumvention objection, the risks of paternalism may provide us with even stronger countervailing reasons to favour a subjective view of welfare. Most importantly, however, the relative insignificance objection rears its head again. For unless the objective account of welfare lists healthcare as the good to be included – a position that would be unjustifiably ad hoc without further reasoning – then we are back to the issue of health not necessarily being promoted through healthcare interventions. The result is a dilemma: either we list health as among the lists of objective goods to be distributed, in which case the relative insignificance objection tells us that healthcare does not actually secure this goal, or we list healthcare as one of the objective goods to be distributed, in which case we are stuck with the task of explaining what makes healthcare morally significant that it requires inclusion in the list. The first horn does not secure the moral significance of healthcare and the second horn leaves us precisely where we started, namely, trying to identify the feature(s) that makes healthcare morally significant.

This is a similar response we could give to those who propose resourcist theories of justice, whereby health or healthcare is to be listed as a resource.Footnote 14 It would still be the case that the value of health(care) cannot be reduced to a resourcist variant of HC2. The reasons that would justify health(care) being a separate resource in the first place falls prey to the same dilemma. If healthcare is to be reduced to the value of health as a resource, it fails because of the relative insignificance objection. If healthcare is itself the resource, it leaves our normative endeavour exactly where we started. Resourcist theories are therefore of no help in vindicating HC2.

The relative insignificance objection, together with the undue narrowness objection and the circumvention objection show that both HC1 and HC2 are empirically and normatively insufficient to ground the moral significance of healthcare. Empirically, the link between healthcare and its supposed function in promoting the ideal is tenuous and contingent. The evidence around the social determinants of health and non-clinical public health initiatives undermine the claim that healthcare is significant because of its impact on population health. Normatively, the arguments advanced by HC1and HC2 are not connected to a central feature of healthcare and are therefore unable to demonstrate moral significance independently of the ideal it supposedly serves.

One potential rejoinder against the relative insignificance objection is worth considering. Someone may argue that we can accept the implications of the relative insignificance objection (as an empirical issue) but nevertheless provide healthcare. This is because we can concede that acting on the social determinants of health and enacting public health initiatives would indeed maximise health outcomes, but we do not need to care about maximisation. It is merely enough that we achieve good enough health outcomes, and healthcare enables us to do this. It is questionable whether justice requires us to aim merely towards a good enough level of population health outcomes or if it demands something more. Let me grant, for the sake of argument, that justice is concerned with securing a good enough level of population health outcomes rather than maximising it. Even with this concession, the rejoinder would not establish the moral significance of healthcare or carve out an argument to value its provision.

Rejecting the ideal of maximising population health outcomes would not entail the moral significance of healthcare or guarantee a role for it. It remains open, for instance, that we should promote some of the social determinants of health to a sufficient level so that we can have a good enough level of population health. The problem of why healthcare is necessary or important for a good enough level of health remains unanswered. Unless healthcare has independent value, it is entirely open that it can be excluded in our aim for a good enough level of health. The relative insignificance objection affects the core claims contained in HC1 and HC2, and this holds independently of whether or not we care about maximising population health outcomes.

We are therefore back to our primary challenge, namely, articulating reasons that enable us to square the powerful intuition we have about the moral significance of healthcare with the reality of the empirical evidence from non-clinical public health initiatives and the social determinants of health. To successfully provide an argument for healthcare’s moral significance, a function that is more centrally related to healthcare needs to be advanced. In the face of these objections, theorists sympathetic to the idea that healthcare is morally significant have turned to more intrinsic justifications based, for example, on public reason liberalism and care ethics (Badano 2016; Horne 2017; Engster 2014). In the remainder of the paper, I follow this general method of defending the moral significance of healthcare by reference to something more centrally linked to it.

3 Vulnerabilities, Respect, and the Moral Significance of Healthcare

Over and above the benefits of healthcare in terms of HC1 and HC2, I argue that healthcare possesses a unique expressive function that is central to its purpose and indispensable for grounding its moral significance:

HC 3 (Expressive View)

The moral significance of healthcare lies in its ability to express respect to individuals in a morally salient and distinctive way.

The Expressive View focuses on individuals (rather than populations) and it is the respect that healthcare expresses to individuals who are inherently vulnerable that imbues healthcare with its moral significance, doing so in a way that does not rely on the empirically and normatively contingent manner of HC1 and HC2. My argument is not that HC1 and HC2 have no role to play in grounding the moral importance of healthcare but that they are incomplete and unable to ground the moral significance of healthcare by themselves. HC3 is an overlooked and central component of establishing the moral significance of healthcare. Except for a very small handful of theorists, philosophers have not seen it apt to theorise the expressive dimension of healthcare.Footnote 15 In what follows, I develop the thought that what makes healthcare morally significant lies primarily in the respect it expresses to individuals rather than its contribution to (population) health or broader notions of justice. I articulate the normative mechanism by which healthcare expresses respect to individuals and, in doing so, aim to ‘rescue’ healthcare from the devastating objections outlined and thereby establish its moral significance.

My argument for healthcare’s expressive function proceeds in two key normative steps: first, to highlight the state of what we can call inherent vulnerability that everyone experiences qua human person, and second, to show that this intrinsic part of our personhood is something healthcare is able to address in a morally salient way. In doing so, it expresses respect to us as individuals, in flesh and blood, with precarious and variable health needs. It is through the reality of our inherent vulnerability and healthcare’s ability to address it that it gains its moral significance and makes it a worthy focus of egalitarian justice.Footnote 16

3.1 Universal Vulnerability

The first step in the argument is to highlight our universal vulnerability qua human persons. Human beings are inherently vulnerable creatures. Susceptibility to death and disease are central characteristics of our personhood. We are all but one mutation away from cancer; one misfortune or accident away from serious injury, disease, or death. The nature of our personhood as human beings is that we are fragile and vulnerable creatures, susceptible to a range of biochemical and physiological forces. Because this reality of vulnerability is inherently tied to our fragile nature as human beings – compared to, say, perfectly engineered robots free of such vulnerabilities – the vulnerability is a universal feature across every person. This view of vulnerability can be referred to as inherent vulnerability.Footnote 17

Martha Albertson Fineman argues that ‘vulnerability is – and should be understood to be – universal and constant, inherent in the human condition … a universal, inevitable, enduring aspect of the human condition that must be at the heart of our concept of social and state responsibility’ (Fineman 2008: 1, 8). Onora O’Neill points to the persistent and universal feature of inherent vulnerability:

‘Human beings begin by being persistently vulnerable in ways typical of the whole species: they have a long and helpless infancy and childhood; they acquire even their most essential physical and social capacities and capabilities with others’ support; they depend on long-term social and emotional interaction with others; their lives depend on making stable and productive use of the natural and man-made world.’ (O’Neill 1996: 192)

Alasdair MacIntyre draws attention to the fact that there is only so much individuals can do in response to their own our inherent vulnerability:

‘How we cope is only in small part up to us. It is most often to others that we owe our survival, let alone our flourishing, as we encounter bodily illness and injury, inadequate nutrition, mental defect and disturbance, and human aggression and neglect.’ (MacIntyre 1999)

Inherent vulnerability can be contrasted with the idea of specific vulnerability, prevalent in the bioethics and research ethics literature. Specific vulnerability focuses on particular individuals or groups who are seen as particularly vulnerable, such as the elderly, those with disabilities, or those who stand in a particular relationship to us. Robert Goodin’s early account of the ethics of vulnerability – in addition to providing a general grounding for the significance of vulnerability in theorising our duties and responsibilities – is both laudable and significant in this respect.Footnote 18 For specific vulnerability, vulnerability is a deviation from the norm and something specific people experience rather than something universally experienced by all. While there is merit to focusing on specific vulnerabilities, the reality of inherent vulnerability is frequently forgotten about. In doing so, we overlook a significant way in which we are all vulnerable and run the risk of failing to recognise the implications of our own vulnerability – for example, in our universal need for care.

It is true, of course, that these vulnerabilities and risks – not least those relating to health and healthcare – are not evenly felt and distributed (Wolff and De-Shalit 2007; Wolff 2009). However, even the richest billionaire is vulnerable to a heart attack or metastatic cancer, no matter what precautions she takes and no matter her surroundings. A member of the dominant group in society will still bleed when we prick him and die when we poison him. While the differences in degrees of vulnerability may itself be a concern of justice, there is something morally significant about the presence of vulnerability simpliciter. A useful thought is to consider the Kantian conception of personhood as linked to the possession of rationality (Kant 2017). Once we are above a certain threshold of rationality, we are considered persons in the Kantian sense. Our humanity does not diminish or increase in proportion to our level of rationality, such that the more rational one is, the more human or the more of a person one is. Above some relevant threshold, our status as persons and the corresponding rights and duties that come with this are equal.Footnote 19 Analogously, on this form of reasoning, the salient feature is the mere presence of vulnerability in the morally relevant degree in each and every human being rather than the relative degrees.Footnote 20

3.2 From Universal Vulnerability to Respect

The second step in the argument is to highlight the role of healthcare in relation to these universal vulnerabilities and how it connotes respect for individuals. Healthcare has an important expressive function, over and above its biomedical function and despite its relatively limited effect on population health outcomes. This expressive function comes from the way healthcare signifies respect to individuals given the reality of inherent vulnerability. Healthcare expresses respect through three principal normative mechanisms, which I call the individuating mechanism, the conceptual mechanism, and the direct mechanism. These mechanisms are not mutually exclusive, not exhaustive, and are consistent with valuing certain aspects of HC1 and HC2.

We can define respect, in the sense we are concerned with, as recognising the dignity, importance, value or significance of an entity independently of one’s own feelings and sentiments towards it. It is tied with what Stephen Darwall calls recognition respect: “The most general characterization which I have given of recognition respect is that it is a disposition to weigh appropriately some feature or fact in one’s deliberations. Strictly speaking, the object of recognition respect is a fact. And recognition respect for that fact consists in giving it the proper weight in deliberation” (Darwall 1977: 39, my emphasis).Footnote 21 This fact, using Darwall’s description above, is the fact of inherent vulnerability. Recognition respect demands that we recognise the fact of inherent vulnerability and feature this in our actions and deliberations. Part of taking this inherent vulnerability seriously, I shall argue, is the provision of healthcare to individuals (regardless of its limited impact on population health). Through providing healthcare to individuals, recognition respect is shown. To understand respect in more practical terms, we can draw on a simple strategy used by Jonathan Wolff, who argues that we can understand the nature and demands of respect by reflecting on what it means for someone else to treat us with respect. Wolff argues that a comprehensive answer is not required: ‘It is not necessary to develop a full analysis of an egalitarian notion of respect, even if that were possible. … Rather I need only make plausible that certain forms of treatment undermine respect: that is, if I feel people are treating me in a certain way, this will either lead me to believe that they do not respect me, or lead me to lose my self-respect’ (Wolff 1998: 107).Footnote 22 Both Darwall and Wolff’s respective conceptions of respect – one more theoretical and one more practical – give us sufficient guidance for now to proceed with illustrating the expressive function of healthcare.

3.3 Individuating Mechanism

The individuating mechanism highlights healthcare’s characteristic focus on the individual. Despite its limited impact on health outcomes at a population level (as the relative insignificance objection demonstrates), healthcare is innately focused on individuals and cognisant of the way inherent vulnerability manifests for specific persons. The inherent vulnerability of the human body means that even in a world with perfect population-level health policies, individuals will continue to fall ill and be afflicted by disease. For these people, it is scant reassurance to say that population health interventions have given them the best possible chance of overcoming their vulnerability. Healthcare plays a vital role in this regard, coming to the aid of individuals who fall prey to the vulnerable reality of the human condition.

To understand how this focus on individuals expresses respect, consider the contrast between healthcare and population-level interventions. Population health generally deals with anonymous statistical figures. When we create inclusive social structures that thereby reduce mortality and morbidity, for example, we cannot point to an individual and say that she is the one who benefited from a population policy. The effects of preventive and population level policies are invisible at the level of the individual, due to the complexities of determining counterfactual outcomes for each individual. Compared to public health and broader policy interventions, healthcare focuses on the individual in a unique way. Healthcare may be the so-called ambulance at the bottom of the cliff, but it serves a vital role in relation to a central characteristic of our personhood; namely, addressing our vulnerability to ill health or at a time of health need. In doing so, it signifies respect to individuals, in flesh and blood rather than primarily as an epidemiological consideration. Even if we believe – as I think we should – that prevention and proactive health measures should have a central role in our policy concerns, it does not follow that there is therefore no need for healthcare and ambulances, any more than supporting crime prevention entails the negation of maintaining an emergency police service.

The individuating mechanism is reminiscent of the debate around identified and statistical lives.Footnote 23 Of particular relevance to my individuating mechanism argument, Johann Frick has argued for the priority of identified over statistical lives on the grounds that we are giving identified individuals a concentrated benefit against certain harm, whereas the benefits to statistical individuals are necessarily more diffused (Frick 2015). In the structure of a typical case – something mirrored in the provision of healthcare versus action on the social determinants of health – we are giving an identified individual a 100% certainty of benefit compared with giving 100 statistical individuals a 1% reduction in risk for a certain condition. My argument thus far is that we ought to favour identified over statistical lives when it comes to expressing respect in the form articulated, but I do not make the stronger (and I think mistaken) claim that we ought to favour identified over statistical lives all things considered.Footnote 24 After all, expressing respect is not all there is to the demands of morality or justice – an issue I return to in Sect. 4.

Another way of expressing the link between healthcare and respect for individuals through the individuating mechanism is that healthcare respects the separatenesss of persons. Unlike population health interventions, which is necessarily aggregative, healthcare focuses on the claims of each individual independently of aggregate benefit. This language appeals to the liberal conception of respect, whereby the ultimate unit of moral concern is the individual who generally has primacy over the collective’s interests. This need not be in tension with the idea that inherent vulnerability requires us to rely on others for care. We can engage in interdependent relations and acknowledge our vulnerability and dependence on others while still believing that individuals are the ultimate unit of moral concern.

Population health measures alone – to wit, an exclusive focus on public health initiatives and action on the social determinants of health – can lead to the neglect of individuals which strikes us as tragic and unbearable. The Expressive View adds a non-consequentialist dimension against a backdrop where much of the discussion is consequentialist in nature. The Expressive View does not challenge the consequentialist dimensions as such, as the aggregate population-level benefits are undoubtedly important; it merely adds a further consideration over and above these, justified at the altar of each individual’s interests.

3.4 Conceptual Mechanism

At a more theoretical level, healthcare demonstrates a very particular kind of respect linked to a central feature of our humanity, in a way that the provision of other services may not do. Healthcare is linked, conceptually, with what it means to acknowledge our inherent vulnerabilities qua human beings. The concept of respecting persons imbued with vulnerability entails the provision of healthcare. We can establish this conclusion by drawing on our considered judgements about the moral and conceptual demands of respecting a vulnerable entity.

Consider how I would ‘respect’ a fragile and ‘vulnerable’ Fabergé egg compared to a rugby ball. By taking exceptional care in handling the Fabergé egg – covering it in silk, cradling it with soft cushions, taking exceptional care in my movements, storing it in a secure safe – I am respecting it qua vulnerable entity. The fragility and vulnerability of the Fabergé egg means that the demands on me are different to the rugby ball. The respect I show for the Fabergé egg is directly based on my acknowledgement of its vulnerability. I would not kick the Fabergé egg in the same way I would a rugby ball, and I would take additional care in how I handle and maintain it. Extending the structure of this conceptual argument, we show respect for human beings’ vulnerability by guaranteeing and providing healthcare, among other things. To fail to do so is to violate the very concept of what it means to respect human beings qua vulnerable beings. It is akin to rolling the Fabergé egg around the garden as a toy or failing to cushion and secure it. To be clear: the Fabergé egg example simply establishes the fact that certain features of vulnerability demand particular responses that directly connotate conceptually whether or not we treat it with respect. The argument is not that human vulnerability is like the Fabergé egg’s or that how we respect a Fabergé egg can be directly translated to how we respect a human person.

At this stage, one might turn the Fabergé egg example against my account of healthcare’s expressive function. Is it not the case, it might be argued, that we are taking preventive steps to stop the Fabergé egg from breaking in an analogous way to acting on the social determinants of health to prevent people from falling ill in the first place? Two responses can be offered. First, as alluded to above, the example is designed to illustrate the conceptual demands of respect rather than to establish something more substantive about the similarities of vulnerability between Fabergé eggs and humans. Second, and notwithstanding the first reply, preventive healthcare focused on individuals is not the same as population-level prevention schemes focused on the social determinants of health. A healthcare professional providing a specific individual with an immunisation against an infectious disease is not analogous to improving the neighbourhood’s social and urban design (i.e., action on the social determinants of health) to prevent that same infectious disease across the population.

It may be said that my account focuses on the ex post, as opposed to the ex ante, dimension, with the Expressive View calling our attention to the significance of the ex post dimension. That is, my arguments about healthcare are concerned with dealing with individuals after illness or injury (ex post), whereas policies targeting public health initiatives and the social determinants of health focus on reducing risks before individuals fall ill or get injured (ex ante). This characterisation of my argument is misleading, and we cannot reduce the debate about the moral significance of healthcare to a mere dichotomy between ex ante and ex post considerations. This is because healthcare is not limited to ex post considerations and deals with many ex ante considerations, including individual-level preventive interventions such as immunisation (which reduces, ex ante, the risk of contracting a disease in the future). The expressive function of healthcare is therefore not concerned merely with ex post considerations, and the expressive function account cannot be collapsed merely to the thought that it is simply another way of articulating the importance of ex post considerations. My argument for the expressive function of healthcare may track the focus on (identified) individuals, but it does not follow from this that I am committed solely to ex post considerations.Footnote 25

A recent proposal by Benedict Rumbold to ground the significance of healthcare on its propensity to meet actual rather than hypothetical health needs is unconvincing and diverges with my strategy in this paper (Rumbold 2021). Not only is the ex ante and ex post distinction – implicit in Rumbold’s account – irrelevant to my account, the distinction he draws between actual and hypothetical health needs is conceptually untenable on its own terms. For example, low calcium that predisposes one to osteoporosis or hypertension that predisposes one to cardiovascular disease seem to be both actual health needs requiring intervention now, as well as hypothetical health needs with future implications. The expressive account of healthcare that focuses on individuals’ inherent vulnerabilities does not fall prey to these considerations.

While the provision of healthcare to a particular individual simpliciter can meet part of the expressive function, only an egalitarian system of universal healthcare in which each and every individual has fair access to healthcare fulfils the conceptual demands of respect and expresses HC3 in full.Footnote 26 This is because the recognition of our inherent vulnerability must be universal for it to serve the respect-expressing function, in the same way respecting and acknowledging fragility means treating all Fabergé eggs with care rather than only those we particularly like. To understand this shift, we can distinguish between two senses in which healthcare expresses respect:

Respect1 (Isolated Respect) – Respect is shown by a healthcare professional who provides treatment to a particular individual. The specific individual is respected in this instance.

Respect2 (Generalised Respect) – Respect is shown by the healthcare system to each and every individual within its scope of responsibility. All individuals are respected in this instance.

It is possible for Respect1 to be realised without Respect2. The US is a good example of this, where many individuals have access to high-quality private healthcare. When these individuals access such healthcare, respect is still shown to them qua individuals with inherent vulnerability. However, Respect2 is a much more demanding condition. The focus is still on clinical intervention for an individual patient, here and now, but from the vantage point of the health system as a whole. The ideal of Respect2 is whether or not Respect1 obtains for each and every individual. This vantage point is not ad hoc and relates to the conceptual demands of respect as well as the reality of collective vulnerability. It starts from the generalised idea that all human beings are vulnerable and extends this thought to recognising the collective vulnerability of humanity. Some vulnerabilities are reinforced as a result of living in larger communities, such as the increased danger from the spread of pathogens or the risk of violence at the hands of others. This collective vulnerability can only be mitigated and addressed, by the mechanisms of respect identified, through the provision of healthcare that is universally accessible in some substantive way. Providing only some people with healthcare does not show respect in the substantive sense of Respect2 because it does not recognise the feature of universal vulnerability that inheres in all individuals.Footnote 27Respect2 does not collapse into population-level action on the social determinants of health as the focus is on the provision of clinical care by healthcare professionals to individuals, rather than on non-healthcare-based interventions with the explicit aim of improving population health.

3.5 Direct Mechanism

Healthcare can address and reduce our vulnerability more directly. If one is severely injured, healthcare reduces our vulnerability not only physically but psychologically. In providing us with healthcare, respect is shown to us, generally at a time when we are at our most needy and fearful. To understand the force of this link, we have only to consider scenarios where we are in great health need and are not provided with the requisite healthcare. Stories abound of people in need being denied healthcare for all kinds of morally irrelevant reasons (including due to lack of ability to pay or because of nationality and ethnicity). Relying upon Wolff’s strategy for understanding the practical demands of respect, we can see that such denial of healthcare is inconsistent with respecting persons, especially given that their vulnerability is inherent and unavoidable. The direct mechanism arguably draws on the moral significance of healthcare captured by HC1 and HC2, but it cannot merely be reduced to these considerations without also understanding the expressive function. After all, if HC1 and HC2 are the totality of our moral considerations, we fall prey to the raft of objections canvassed in Sect. 2.

Healthcare also provides us with a means to transcend, in a sense, our inherent vulnerability. It weakens the link between the practical reality of our lives and our inherent vulnerability. When riding a bicycle around town or going for a stroll along the meadow, the availability of healthcare provides us with important assurance that we are looked after should misfortune strike us.Footnote 28 Healthcare, in this sense, is agency promoting in an important way. The mere knowledge that healthcare is available to us should something go wrong is anxiety-reducing and enables us to face our inherent vulnerability more candidly.

These three mechanisms are a set of non-exhaustive and non-mutually exclusive features that demonstrate the expressive function of healthcare. Another way to think of my aim in highlighting the expressive function of healthcare is to place the traditional focus on ‘health’ at the same level as the ‘care’ component of healthcare. Healthcare is significant not only in its impact on health, limited though it may be at the population level, but in the way it signifies respect (through the provision of care) to individuals characterised by inherent vulnerability.

4 Objections and Concerns

The expressive function of healthcare may be a shift from how we typically view the moral significance of healthcare and is likely to elicit some objections. I explore four such major objections. The first objection casts various doubts about the moral significance of the ‘expressive function’. The doubt can manifest in reservations about the value or possibility of expressivism; doubt about whether the expressive function can justifiably motivate demanding duties of justice; and scepticism about the significance of respect. The second objection points to a problem all accounts of health(care)’s significance must grapple with, namely, whether the account strikes the right balance between being appropriately narrow and broad. The charge is whether my account can consider minor conditions such as mild eczema, on the one hand, and whether my commitment to healthcare on the grounds of its link to vulnerability also requires me to support the moral significance of other policies around social welfare or housing, on the other hand. The third objection concerns paternalism, and whether healthcare still has expressive value when provided against the will of individuals. The fourth objection highlights a way in which my account might be self-defeating, given that acting on the social determinants of health might also express respect.

4.1 Objection 1: Doubts About the Expressive Function

One powerful objection against grounding the moral significance of healthcare on its expressive function is to cast doubt on the idea of expressivism altogether. Writing in another context, Jason Brennan and Peter Jaworski criticise what they call semiotic or symbolic objections (Brennan and Jaworski 2015). For Brennan and Jaworski, the social meaning of something does not in itself provide a normative reason to act or refrain from acting a certain way. Applying their argument to healthcare, the objection is that the social meaning healthcare expresses is highly contingent and socially constructed and does not provide us with sufficient normative reason to value it. In response, notice that I am not concerned with the social meaning of healthcare. My argument is more conceptual, highlighting the demands of addressing vulnerability and the way this expresses respect given certain starting presuppositions (such as Darwall’s recognition respect) in a way that does not rely upon highly contingent, socially constructed meanings. In this regard, Brennan and Jaworski’s criticism of semiotic arguments may not land against mine.

To respond more fully to critics of expressivism, and those not satisfied with the above response to Brennan and Jaworski, we can point to the diverse ways in which expressivism (of which symbolic value is a component) occupies a central and inseparable role in our moral and social universe. The very act of a romantic kiss, for example, derives its meaning from the expressive and symbolic dimensions of what it connotes. Reducing the act to a description of the movement of the mouth muscles involved does not do justice to the social significance of such an action. Other examples abound in historical and contemporary societies: the obsession with national flags, anthems and other symbols; the idea of martyrdom and dying for one’s cause; many acts of protest and civil disobedience; and countless social, cultural and religious rituals. These actions all gain their moral significance in a large part because of their expressive function. To cast doubt on the idea of expressivism is to ignore a central way in which our lives are given meaning in the social and political universe we occupy – a view acknowledged by a wide variety of theorists, from Elizabeth Anderson to Robert Nozick (Anderson and Pildes 2000; Nozick 1993).Footnote 29 Nozick explicitly acknowledges that the views he presented in Anarchy, State, and Utopia failed to take into account the importance of symbolic and expressive dimensions: ‘The political philosophy presented in Anarchy, State, and Utopia ignored the importance to us of joint and official serious symbolic statement and expression of our social ties and concern and hence … is inadequate’ (Nozick 1993, 32). This argument, however, may still leave some unconvinced about healthcare having an expressive function in this regard. In response to these sceptics, I can only point again to the starting point of inherent vulnerability experienced by each individual and the mechanisms in which healthcare expresses respect through the recognition of this fact, and to appeal to the conceptual understanding of respect and their considered judgements of what an alternative state of affairs might look like.

Another argument is to argue that expressivism is not strong enough to motivate state action or individual obedience, on grounds that it is a morally irrelevant criterion to support a law or policy. The provision of healthcare demands significant regulation and tax payments, and there may be doubt whether the fact that it expresses respect is a strong enough reason to compel obligations on the part of citizens. In response, we can offer three rejoinders. First, we can double down and reassert the importance of expressing respect and the ways in which healthcare meets these conditions, as my foregoing arguments highlight. Second, we can point to analogous cases outside of healthcare where the expressive dimension of particular policies are central considerations. Joel Feinberg, for example, defends an influential account of punishment, whereby its role is to express disapprobation towards wrongdoers (Feinberg 1965). Much of the jurisprudence around anti-discrimination law (especially concerning indirect discrimination) is strongly motivated by ideas related to the symbolic and expressive wrong associated with it (Sunstein 1996; Anderson and Pildes 2000). Many countries’ provision of welfare benefits in cash, rather than in voucher form, is motivated strongly by concerns about expressing dignity to beneficiaries. The provision of many government services is thus already motivated by the expressive dimension.Footnote 30

Third, the claim is not that healthcare has only an expressive function and does nothing else. After all, if this were the case, it would remain an open question whether we ought instead to express respect to individuals in other, more effective non-healthcare-related ways. Instead, the claim is that healthcare may have a relatively insignificant role at the bar of population health when compared to public health initiatives and action on the social determinants of health (the relative insignificance objection), but it has a vital effect on individuals’ health. This effect on health, albeit limited in form and focused on the individual level, is central to the Expressive View of healthcare. It is precisely because of the way healthcare addresses inherently vulnerable individuals’ health needs that it expresses respect. The objection against the Expressive View on the grounds that we have no reason to support healthcare merely for the sake of expressivism is therefore misled, as the expressivism is itself tied to the provision of important health benefits for individuals.

A related concern is the vague and indeterminate nature of respect. Many moral and political philosophers are suspicious about the way in which ‘respect’ is carelessly thrown around as a catch-all term, coming to signify everything and nothing at once. Two responses can be offered against this objection. First, I am concerned with a particular notion of respect, namely, recognition respect. Insofar as I have provided a working definition of this concept, including its link to the recognition of the relevant fact and feature of inherent vulnerability in human persons, it is harder to accuse my account of vagueness, in the same way we might criticise (for example) the vague concept of ‘dignity’ in international human rights law. Second, there is a sense in which we can use the concept of respect as a catch-all term. This is because not much actually turns on the precise term we use for what healthcare expresses. If we want, we can use the language of equal concern (healthcare expresses equal concern for our universal vulnerabilities), interests or needs (healthcare expresses the view that our interests or needs matter equally qua vulnerable entities), or rights (healthcare expresses rights that we have in virtue of, or grounded on the fact of, our shared vulnerable condition) instead of or alongside respect. The expressive function account, then, can be ecumenical and indifferent to our preferred language of justice without diluting its substantive claims.

4.2 Objection 2: Simultaneously Too Narrow and Too Broad

Consider, first, the charge of undue narrowness – the same one Segall levies against Daniels’ account. One might be convinced that providing essential healthcare services (such as emergency medical treatment or cancer surgery) expresses respect for individuals in the sense I have articulated but voice scepticism at whether treating minor conditions (such as mild eczema) really expresses respect for individuals in the same sense. Several comments can be offered in response. First, minor conditions such as mild eczema or mild asthma are still linked to our inherent vulnerability. It is because of the reality of our inherent vulnerability that we suffer from conditions such as asthma and eczema, be they minor or serious in form. In this regard, my arguments about expressing respect through recognising and addressing our inherent vulnerabilities in Sect. 3 still holds. Second, we could imagine a situation in which we seek healthcare for minor eczema, (which is a nuisance and causes us itchiness but is otherwise benign) but are declined such care by the provider or state on grounds that the condition is minor. Using Wolff’s strategy for understanding the practical demands of respect, we would invariably conclude that such a policy does not express respect for us qua vulnerable individuals.

Third, the fact that something expresses respect gives us a central but nonetheless pro tanto reason rather than an all-things-considered reason for providing it as a matter of (egalitarian) justice. We can accept that addressing minor conditions expresses respect to individuals without holding on to the view that addressing such conditions is always demanded by justice all things considered, or that addressing minor conditions is on par with addressing more serious conditions. How exactly we ought to balance considerations of expressing respect and other competing demands of justice is beyond the scope of this paper, but the fact that such balancing is possible should reassure sceptics who resist the thought that treating minor conditions expresses respect on the grounds that this would make healthcare justice unduly demanding.

Consider, second, the charge of undue broadness. This objection focuses on the implications of my account for other vulnerability-reducing goods in society, such as welfare benefit payments or social housing, and whether they are also morally significant due to their function in expressing respect for our vulnerability. In response, it is important to note that healthcare is innately focused on the individual, expressing respect through the three normative mechanisms, grounded in its relationship with our vulnerability as human beings. While the provision of other vulnerability-reducing, respect-promoting goods (such as welfare benefits) is important, they operate at a more superficial level compared with healthcare. The requirement for money in order to reduce our vulnerability to poverty (for example) is not fundamentally linked to our personhood. It is contingent upon, among other things, an alterable structure that relies upon the commodification of essential goods. Our inherent vulnerability is significantly less alterable and makes healthcare much more central to our personhood. For as long as we are subject to the vicissitudes of our body’s biomedical processes, from mutations to so-called lifestyle diseases, healthcare will continue to have a central role to play in addressing our vulnerabilities in a way that other social policies may not.

The objection is different, however, when it draws attention to other vulnerabilities that are similarly inherent in our human condition, such as our requirement for food, water, and shelter. At the same time, the response is simple. I do not make the claim that healthcare is the only good that possesses an expressive function, and it poses no problem to the account if other analogous vulnerability-reducing goods are also treated as parallel in moral significance. In the case of basic needs such as water and food, however, the consequentialist reasons are likely to be stronger than the expressive reasons we have for supporting its provision as a matter of justice. After all, the provision of basic needs at the population level is not prone to analogous objections against HC1 and HC2 outlined in Sect. 2.

This does not entail that we ought to provide these other vital goods in the same manner as we do with healthcare. For example, guaranteeing the provision of food does not necessarily mean establishing a ‘universal food service’, in the same way we have a universal healthcare system. The existence of state-funded universal healthcare is a response to the practical, and policy- and market-related complexities of delivering healthcare, not present in food provision. Most people cannot perform surgery and the provision of healthcare suffers from well-known market failures.Footnote 31In contrast, we do not need a Ministry of Food to guarantee that most people can secure food, at least in normal circumstances.

4.3 Objection 3: Paternalism

A third objection is concerned with the expressive function account opening the floodgates to paternalism. Because I have grounded the moral significance of healthcare on the way it addresses our vulnerability (and in doing so, expressing respect for us qua individuals), it might be an implication of the account that even non-consensual healthcare, insofar as it addresses our vulnerability, expresses respect for the individual. This implication, if it follows, would indeed be highly troublesome. One response is to argue, as many healthcare professionals do, that receiving healthcare to address a health need is objectively valuable whether or not one wants it. There is thus always a pro tanto respect shown in providing healthcare, but this might be outweighed in an all-things-considered way. This is not a particularly appealing response, however, as few of us would want to hold the view that there is even one sense in which forced healthcare is expressive of respect.

A second, more promising response, is to focus on the way in which my account focuses on guaranteeing access to healthcare as a matter of justice, not on ensuring it is actually provided to patients. Of course, the provision should have robust desiderata around fair and equitable access, to ensure that those who need it can access it, but this does not mean that respect is expressed only when treatment is provided. While there is an important grain of truth to this response, it risks undermining the way in which the actual delivery of healthcare to a needy individual does express respect in the way I canvassed in Sect. 3. A third, and I think the best response, is to simply observe that from the fact that something is good if it is freely chosen and accepted, it does not follow that something is still good if it is not freely chosen and not freely accepted. Freedom is good if freely accepted but being forced to be free may not be. Engaging in sex is good when freely accepted but being forced to have it is evidently not good. Money may be good when freely accepted, but it is less clear that it is good if it is thrust upon someone who rejects it. Analogously, healthcare may express respect (and be good) when it is subject to widely accepted norms of consent and autonomy but it fails to express respect (and may express disrespect and violate rights) if it breaches these norms.

4.4 Objection 4: Self-Defeat

A fourth and final objection is whether my defence of the moral significance of healthcare is self-defeating on the grounds that it would still fall prey to the objections I canvassed in Sect. 2. The thought is that we would express respect equally, if not more, if we prevented people from falling ill in the first place through non-clinical public health initiatives or broad action on the social determinants of health. Public health actions and interventions on the social determinants of health therefore also have an expressive function.

First, I have argued that there is something significant in the way healthcare focuses on needy individuals, here and now, in flesh and blood rather than as statistical considerations at a population level. This is something that action on the social determinants of health, which is necessarily aggregative and population focused, cannot take into account. The expressive function of public health actions and interventions on the social determinants of health are much harder to establish at the altar of each individual’s right to respect and therefore does not meet the bar of expressing respect to individuals to the same level as healthcare. There are important reasons to act on the social determinants of health and other population-level concerns, but this can be for reasons that are different from reasons for providing healthcare.

Second, and relatedly, one can accept my arguments about the expressive function of healthcare and believe that we ought to devote more funding than we currently do to action on the social determinants of health. My central claim about the expressive function of healthcare would not be challenged, as I do not argue that healthcare should be pursued exclusively, at the expense of non-clinical public health initiatives or action on the social determinants of health. Third, as I noted in response to a previous objection, none of this precludes healthcare professionals from engaging with individual patients on preventive healthcare to prevent them from falling ill in the first place. Such treatment, such as giving proactive advice on mental health resilience or administering a vaccine, does not necessarily treat an actual or ex post health need, but it is still focused on recognising the vulnerable nature of individuals’ health.

5 Conclusion

This paper has argued that what makes healthcare morally significant is its expressive function. Over and above its influence on health and other metrics of justice, and in spite of its relatively limited impact on population health outcomes, healthcare expresses respect for individuals in a distinctive and morally salient way. The respect-expressing dimension of healthcare is linked to the fact that healthcare characteristically focuses on individuals, addressing our inherent vulnerability as human beings in three central ways and, in doing so, signifying respect to us qua persons. This respect-expressing function of healthcare provides a central argument for acknowledging the moral significance of healthcare and for supporting its universal provision as a matter of egalitarian justice. Despite my paper not outlining specific policy recommendations, the expressive function framework provides general guidance for what practical options would best realise the respect-promoting dimension of healthcare. Not only does grounding the moral significance of healthcare on its expressive function escape many of the objections against the role of health in an egalitarian theory of justice, but it also promises to bring the practise of healthcare closer to what many feminist theorists have pointed out all along: the importance of care, expression and communication, and the recognition of our inherent vulnerability and dependence.

Notes

I take it as a starting point that egalitarian theorists are right that there is something morally significant about the provision of healthcare in a theory of justice. My role is not to challenge this conceptual starting point, but to show that prevailing accounts may be mistaken and that we need a revised conception of why we ought to care about healthcare in (egalitarian) theories of justice.

For such an argument, see (Sreenivasan 2007).

I am not explicitly concerned about proposing specific policy options. My claim is simply that viewing the special moral significance of healthcare in this way will have implications for the practice and policy of distributive justice and can provide a general framework for how the state ought to treat health within a general theory of justice.

Health and healthcare are therefore conceptually distinct, and the fact that one is morally significant would not entail the moral significance of the other. Health being morally significant would not entail the significance of healthcare.

A similar point has been made by James Wilson: (Wilson 2009)

The underlying thought of the Health View, for the sake of absolutely clarity, is that healthcare promotes the health of the population, and this is what makes it significant for a theory of justice.

Daniels subsequently extends this argument to take into account all factors that impact on health, but this is a matter for the next section. Jennifer Prah Ruger also supports the Justice Function account of healthcare’s moral significance: (Ruger 2007)

Susan Hurley, for example, has examined why many find it objectionable to undertake levelling down in the realm of health: (Hurley 2006)

Of course, this is not the same as saying healthcare has no significant impact on individuals’ health. This is the crux of a constructive argument I develop in Sect. 3.

Sreenivasan’s primary concern may be about promoting health for the sake of promoting equality of opportunity (rather than about promoting health directly), but any challenge to the link between healthcare and health will affect this argument. As I stated earlier, those who argue for the view that healthcare will promote health which will then promote equality of opportunity must still rely upon the link between healthcare and health. This first step is needed to link the argument.

For a broader discussion of the appropriate relationship between empirical evidence and normative theorising, see (Go 2020).

That people frequently prioritise other pursuits above health is testament to the fact that non-health-related welfare is often seen as more important. Think, for example, of choosing to live in a more polluted city for a higher salary, going skiing for the fun despite the risk of injury, driving cars for the convenience despite the risks, or eating fried chicken for the taste despite its link to cardiovascular disease.

See, for instance, (Dworkin 2000: 286)

For a more detailed account of the moral significance of vulnerability and why it matters for our normative theorising, see (Goodin 1985).

Goodin defends an object-centred account of vulnerability: A is vulnerable to B iff B’s acts or omissions have the potential to (severely) impact A. (Goodin 1985)

Even if there are some things we can be ‘certain’ about – for example, by undertaking a genetic test that will confirm that one will not develop a particular disease – the human body is still prone to a whole raft of vulnerabilities. There are still unknown pathogens that could kill us, or we could be involved in an accident on our way home. There are thus enough sources of vulnerability to motivate my account, for as long as our bodies remain inherently vulnerable in a plethora of different ways.

See also (Darwall 2006).

This is not merely a subjective account of respect, whereby disrespect is present when or only if one feels disrespected. Rather, it is an illustrative tool for us to understand the demands of respect, akin to an (objective) ideal observer account of respect.

Frick’s argument for the priority of identified lives is similar, arguing that it is open what we ought to do, all-things-considered.

I remain deliberately ambivalent about what ‘fair access to healthcare’ constitutes, as there are many compatible accounts, from single-payer systems such as the UK’s NHS to multi-payer universal healthcare such as Australia’s Medicare programme or universal social insurance schemes common in Europe.

For further discussion on health(care) as a positional good and its egalitarian implications, see (Brighouse and Swift 2006).

Jonathan Wolff mentions the importance of ‘health security’ in this regard: (Wolff 2012)

For further discussion on the expressive dimension of state action, see (Voigt 2018).

For more a recent analysis of market failures and its role in justifying healthcare provision, see (Horne and Heath 2022

References

Acheson, Donald. 1998. Independent Inquiry into Inequalities in Health Report. Department of Health and Social Care.

Adams, Robert Merrihew. 1997. “Symbolic value”. Midwest Studies in Philosophy 21(1): 1–15.

Anand, Sudhir. 2006. “The Concern for Equity in Health.” In Public Health, Ethics, and Equity, eds. Sudhir Anand, Fabienne Peter and Amartya Sen. Oxford University Press.

Anderson, Elizabeth, and Richard Pildes. 2000. “Expressive theories of Law: a General Restatement”. University of Pennsylvania Law Review 148(5): 1503–1575.

Badano, Gabriele. 2016. “Still Special, despite everything: a Liberal Defense of the value of Healthcare in the Face of the Social Determinants of Health”. Social Theory and Practice 42(1): 183–204.

Barker, Abigail, and Linda Li. 2020. “The cumulative impact of Health Insurance on Health Status”. Health Services Research 55(2): 815–822.

Black, Douglas, Peter Townsend, and Nick Davidson. 1982. Inequalities in Health: the Black Report. Penguin Books.

Boorse, Christopher. 1977. “Health as a theoretical Concept”. Philosophy of Science 44(4): 542–573.

Brennan, Jason, and Peter Jaworski. 2015. “Markets Without Symbolic Limits.” Ethics 125(4): 1053–1077.

Brighouse, Harry, and Adam Swift. 2006. “Equality, Priority, and positional Goods”. Ethics 116(3): 471–497.

Butler, Judith. 2004. Precarious Life. Verso.

Butler, Judith. 2009. Frames of War. Verso.

Callahan, Daniel. 1973. “The WHO definition of ‘Health’.”. Hastings Center Report 1(3): 77–87.

Cohen, Glenn, Norman Daniels, and Nir Eyal. 2015. Identified Versus statistical lives. Oxford University Press.

CSDH, and Michael Marmot. 2008. Closing the Gap in a Generation WHO.

Daniels, Norman. 1985. Just Health Care. Cambridge University Press.

Daniels, Norman. 2007. Just Health. Cambridge University Press.

Darwall, Stephen. 1977. “Two Kinds of Respect.” Ethics 88(1): 36–49.

Darwall, Stephen. 2006. The second-person standpoint. Harvard University Press.

Davis, Ryan. 2019. “Symbolic values”. Journal of the American Philosophical Association 5(4): 449–467.

Dworkin, Ronald. 2000. Sovereign Virtue. Harvard University Press.

Engster, Daniel. 2014. “The Social Determinants of Health, Care Ethics and Just Health Care”. Contemporary Political Theory 13(2): 149–167.

Feinberg, Joel. 1965. “The Expressive Function of Punishment.” Monist 49(3): 397–423.

Fineman, Martha Albertson. 2008. “The vulnerable subject: Anchoring Equality in the Human Condition”. Yale Journal of Law and Feminism 20(1): 1.

Fogel, Robert. 1986. Nutrition and the decline in Mortality since 1700: some additional preliminary findings. Cambridge: National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc.

Frick, Johann. 2015. “Contractualism and Social Risk”. Philosophy & Public Affairs 43(3): 175–223.

Go, Johann. 2018. “Should gender reassignment surgery be publicly funded?”. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry 15(4): 527–534.

Go, Johann. 2020. “Facts, principles, and global justice: does the ‘Real world’ Matter?” Critical Review of International Social and Political Philosophy: 1–21.

Goodin, Robert. 1985. Protecting the vulnerable. University of Chicago Press.

Hausman, Daniel. 2006. “Valuing Health.” Philosophy and Public Affairs 34(3): 246–274.

Hope, Tony. 2001. “Rationing and life-saving treatments: should identifiable patients have higher Priority?”. Journal of Medical Ethics 27(3): 179–185.

Horne, L., and Chad. 2017. “What makes Health Care Special? An argument for Health Care Insurance”. Kennedy Institute of Ethics Journal 27(4): 561–587.

Horne, L., Chad, and Joseph Heath. 2022. “A market failures Approach to Justice in Health”. Politics Philosophy & Economics 21(2): 165–189.