Abstract

According to John Rawls’s famous Liberal Principle of Legitimacy, the exercise of political power is legitimate only if it is justifiable to all citizens. The currently dominant interpretation of what is justifiable to persons in this sense is an internalist one. On this view, what is justifiable to persons depends on their beliefs and commitments. In this paper I challenge this reading of Rawls’s principle, and instead suggest that it is most plausibly interpreted in externalist terms. On this alternative view, what is justifiable to persons is not in any way dependent on, or relativized to, their beliefs and commitments. Instead, what is justifiable to all in the relevant sense is what all could accept as free and equal. I defend this reinterpretation of the view by showing how it is supported by Rawls’s account of the freedom and equality of persons. In addition, a considerable advantage of this suggestion is that it allows for an inclusive account of to whom the exercise of political power must be made justifiable.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

One of the classical problems in political philosophy is the problem of political legitimacy. This is the problem of whether, and in virtue of what, a government may possess the right to rule.Footnote 1 According to one currently influential approach to this problem, formulated by John Rawls as the Liberal Principle of Legitimacy, it is a necessary requirement for political legitimacy that the exercise of political power is “justifiable to all” (2001: 141). Putting some of the specifics of Rawls’s view aside, the core idea that has gained such a significant following among liberal political philosophers may be formulated as follows:

The Liberal Principle

The exercise of political power is legitimate only if it is justifiable to all citizens.Footnote 2

On this view, justifiability to citizens is a necessary requirement for governmental legitimacy as well as the legitimacy of the actions performed by a government.Footnote 3 That the exercise of political power needs to be justifiable to citizens means that political legitimacy, in a particular society, depends on justifiability to the members of that society. But what does it take for some act on the part of a government (or some law, policy, or institution) to be justifiable to the relevant persons? One possible view is that for it to be justifiable to these persons it must be the case that they could, from their particular perspectives – on the basis of their beliefs and commitments – come to see it as acceptable or justified. An interpretation of justifiability to persons along these lines can be characterized as internalist. In general terms, it construes justifiability to a person in such a way that what determines whether something is justifiable to some particular person is what she happens to believe and value, and what is relevantly accessible to her from this perspective of hers.

The internalist interpretation is currently the dominant interpretation in the literature on liberal legitimacy. Indeed, it appears to be almost universally assumed that internalism is an essential feature of the Liberal Principle.Footnote 4 The main aim of this paper is to challenge this assumption. In order to do so I shall suggest, and defend, an alternative externalist interpretation of what justifiability to persons consists in. On this view, justifiability to persons does not depend on the beliefs and commitments they may hold. Something being justifiable to a person is thus not a matter of what this particular person could be brought to accept from her particular perspective, and her specific beliefs and commitments. Instead, what is justifiable in the relevant sense is determined by moral standards that are not themselves derived from such facts about what persons happens to believe and value. More specifically, what is justifiable to all in the externalist sense that I shall propose is what all could accept as free and equal.

In brief, what I shall argue is the following. The proper ground on which to decide between internalism and externalism is not, as some advocates of the Liberal Principle appear inclined to believe, considerations relating to solving the problem of stability that Rawls addresses in his Political Liberalism. Instead, we should choose between them in the light of which most accurately captures how we are to treat persons in order to treat them as free and equal. This crucially depends on how the freedom and equality of persons should be understood. I distinguish between two very different accounts of freedom and equality, and show how a Rawlsian view provides a foundation for externalism. Finally, I offer further support for my suggested reinterpretation of the Liberal Principle by showing how it makes possible an inclusive account of to whom justifiability is owed. This last point illustrates how important the choice between internalism and externalism is, in the continued search for the most plausible interpretation of this influential approach to political legitimacy.

I shall advance my view as an interpretation of the Rawlsian idea that political legitimacy requires justifiability to all citizens. I expect that some will take issue with this on exegetical grounds, since how to best interpret Rawls is a difficult and highly controversial topic. In response to such worries, I want to emphasise that my primary aims in this paper are not exegetical. What I argue is that the externalist interpretation results in a philosophically more compelling account of political legitimacy than internalism does, not that it provides the most accurate depiction of Rawls’s thinking on these matters. Hence, though I believe that my view is in important respects in line with core Rawlsian ideas – in particular, the conception of free and equal persons – I would not consider it a decisive objection if it turns out that it departs from other aspects of the theory of Rawls. The view that I defend here should thus be of interest to all those who find the Liberal Principle appealing, regardless of one’s preferred reading of Rawls.

2 Internalism and Externalism about Justifiability to Persons

That something is justifiable to certain persons is not the same as it simply being morally justified. If it were, then talk about justifiability to persons would be superfluous. Rather, that something is justifiable to someone is supposed to consist in something like it being acceptable to the person. On most views, however, the relevant form of acceptance is not actual acceptance. Rather, what determines whether something is justifiable to someone is whether he or she could, in some specific sense, accept it. Internalism and externalism can be understood as supplying two completely different accounts of how to construe this “could”.

Let us first look at internalism. It is evident that this is the dominant interpretation among both adherents and critics of the Liberal Principle. Here are just a couple of typical expressions of the view. Jonathan Quong holds that what is justifiable to a person depends on what he or she “is justified in believing”. This, in in turn, depends on what is “accessible to” the person, and his or her “wider epistemic situation” (2011: 141–142). In an attempt to capture what all versions of the view have in common, Fabian Wendt characterizes justifiability to an individual as being “relative to the individual’s values and beliefs, not relative to some external standard” (2019: 40). Similarly, Chad Van Schoelandt claims that all who are committed to some version of the Liberal Principle “commit to a mode of justification internal to, or starting from, the beliefs and values of citizens” (2015: 1032). Finally, consider David Enoch’s characterization of this account of political legitimacy (which he does not endorse) as the idea that the legitimacy of a political authority must “be somehow accessible to” those subjected the authority. The general idea being, according to Enoch, that “unless an authority can be justified to you pretty much as you are, it does not have legitimacy over you” (2015: 114–115, emphasis in original).Footnote 5

The general internalist approach expressed in these statements can be fleshed out in different ways, resulting in different accounts of what justifiability to persons consists in.Footnote 6 I shall here not consider how such forms of internalism may differ, but instead focus on what they all have in common. What they have in common is the following. What someone could accept in the relevant sense – and hence what is justifiable to him or her – is taken to be a matter of what is accessible to the person, where the relevant form of accessibility is understood in such a way that what is accessible is significantly limited by the beliefs and commitments that the person holds. Hence if what two persons believe is sufficiently different, what is justifiable to one of them may not be justifiable to the other. Since what is justifiable to these two persons “starts from” (Schoelandt) and “is relative” (Wendt) to the beliefs and values of these two persons, what is relevantly “accessible to” (Quong and Enoch) them is constrained by these particular beliefs and values.

The externalist alternative that I shall defend in this paper rejects this dependence on the beliefs and commitments of persons. On this alternative view, what persons in the relevant sense could accept – and hence what is justifiable to them – is not constrained by, or in any way relative to, what they happen to believe and value. As an example of the kind of view that I have in mind, consider the famous contractualism of T.M. Scanlon. On Scanlon’s view the moral rightness of an act depends upon whether it is allowed by principles that can be justified to others. Whether principles can be so justified depends, in turn, on whether they could reasonably be rejected by people who were motivated to find principles for the general regulation of behaviour that others, with a similar motivation, could not reasonably reject (1998: 4).

According to this view, what determines the reasonable rejectability of a principle is the moral reasonableness of possible objections to it, from the points of view of those who would be relevantly affected by the actions under consideration. Importantly, however, the reasonableness of such objections is not dependent on the particular aims and interests that different people may have. Rather than being dependent on such characteristics of particular individuals, they depend on the generic reasons that people have in virtue of occupying certain positions (Scanlon 1998: 194, 204).

A consequence of this view is that it makes no difference exactly who it is that occupies the relevant positions (Kumar 2009: 261). What can be justified to me, for instance, is not dependent on the specifics of my point of view. What would be reasonable for me to object to is the very same as what would be reasonable for some other person, were he or she instead to occupy my position, to object to. The moral reasonableness of rejecting a principle is thus based on normatively relevant general facts about persons, and the various positions they may find themselves in. Hence this view denies what internalism asserts, namely that justifiability to persons is constrained by, or relative to, what they believe and value. What could be accepted (or not rejected) in the relevant sense is simply independent of such facts about persons.Footnote 7 Something can thus be justifiable to some group or persons in the externalist sense without it being justifiable to them in the internalist sense, and vice versa.Footnote 8

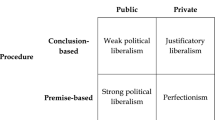

On the externalist view, justifiability to a person is determined by what is reasonable, in a moral sense, to accept or reject from the person’s standpoint understood in generic terms. Hence externalism employs a moral notion of reasonableness that has no place in internalism. Internalists often employ the notion of reasonableness as well, but when they do, they apply it to a different element of their interpretation of the Liberal Principle. They typically specify the citizens to whom justifiability is required as “the reasonable” only, thereby excluding those who fail to qualify as such.Footnote 9 But as I shall explain in Sect. 5 below, this is a move made necessary precisely because the internalist account of justifiability to persons is lacking the moral content we find in externalism. It makes it possible to affirm an internalist version of the Liberal Principle, and yet avoid the libertarian or anarchical implications that would otherwise seem to follow.Footnote 10

It should be emphasized that, just as in the case of internalism, externalism can be fleshed out in different ways. Scanlon’s account of reasonable rejectability is merely one possible way of doing so, and nothing in this paper will depend on the details of this specific externalist view. What I am interested in is the choice between internalism and externalism as such, in the context of trying to identify the most plausible interpretation of the Liberal Principle.

2.1 Other Alternatives?

Before proceeding, it is necessary to offer some further support for my proposed taxonomy. Some may think that there are other relevant positions that ought to be taken into account here, and I shall consider two such suggestions: hypothetical forms of internalism, and hybrid views. My take on these is that the former is not, despite appearances, a distinct view at all. The latter might be, but we are presently lacking a clear account of what such a view would look like.

In my exposition of internalism above, I included Quong on the list of internalists. However, there is one feature of Quong’s view that one may take as evidence that this is a mistake. Quong repeatedly claims that the “justificatory constituency” – the persons to whom the exercise of political power must be justifiable – consists of a “hypothetical” group of reasonable citizens (2011: 144). This might be taken to suggest that he construes of justifiability to these hypothetical persons in the internalist sense, but that the result is a different form of internalism. Perhaps this form of hypothetical internalism, as we might call it, is a distinct alternative that should be taken into account?Footnote 11

In order to determine this matter, we need to consider how to understand Quong’s claim that the justificatory constituency is a hypothetical one. This is far from clear, but one interpretation is to take him as suggesting that what is justifiable to real persons is determined by what is justifiable to hypothetical reasonable persons. Justifiability to these hypothetical persons is then construed in internalist terms – by reference to their stipulated reasonable moral beliefs – resulting in a view where what is justifiable to real persons is a matter of what they would accept if they were to hold these beliefs as well. The result, it may seem, is a distinct form of internalism; one that appeals to the beliefs of these hypothetical persons, not to the beliefs of real people.

But this is not, despite appearances, a distinct form of internalism at all. Rather, it is a form of externalism, though one formulated in internalist-sounding terms. Externalism, remember, construes justifiability to persons in such a way that what is justifiable to them is independent of their beliefs and commitments. On the interpretation considered above, Quong would turn out to be an externalist in precisely this sense. The seemingly internalist element would concern the beliefs and commitments of the hypothetical persons, not the real persons to whom the exercise of political power is to be made justifiable. Hence, if we were to incorporate this view into the Liberal Principle, we would arrive at a version of it where what is justifiable to the citizens over whom political power is being exercised is independent of their beliefs and commitments. This is, quite clearly, an externalist version of the principle.

So, rather than motivating the introduction of another distinct position, the above interpretation would motivate removing Quong from the list of internalists altogether. But I think that would be a mistake, since portraying Quong as an externalist makes it exceedingly difficult to make any sense of other parts of his theory. In particular, it would make it completely mysterious as to why he excludes the unreasonable – who he clearly treats as real people, not hypothetical ones – from the justificatory constituency. Externalism, as I explain in Sect. 5 below, makes such a move entirely unnecessary. I therefore believe that another interpretation is more charitable, and comes closer to capturing Quong’s actual view. What Quong is trying to avoid is any reliance on the beliefs and commitments of “actual citizens” in “current liberal democratic societies” (2011: 144). He wants to explain how the exercise of political power can be made legitimate in another kind of society; a well-ordered liberal society, populated by reasonable persons. He therefore holds a view that requires justifiability in the internalist sense to real persons, but the relevant group of persons – the reasonable citizens of a well-ordered society – is hypothetical in the sense that it is not a currently existing one.Footnote 12 I therefore believe that Quong is, after all, an internalist in my sense.Footnote 13

Let me now turn to the other suggestion: hybrid views. Such views appear to be possible since we can imagine a view according to which justifiability to persons depends on the beliefs and commitments that they hold, in some combination with certain external moral constraints. Charles Larmore appears, somewhat hesitantly, to embrace such a view. Larmore explicitly admits that his liberal view excludes those who do not share certain moral convictions. He denies that “the basic terms of our political life must be justifiable to citizens who reject the cardinal importance of the search for common ground amid different convictions about the essence of the human good” (2015: 85). The idea apparently being that a liberal order will not be justifiable in the internalist sense to those who do not share certain liberal convictions, most importantly an idea of respect for persons. But Larmore then goes on to suggest that those who are excluded are not excluded altogether. Instead, it can be claimed that only certain beliefs of theirs are excluded, and that a liberal order can be made “justifiable to such people as well, on the assumption – counterfactual in their case – that they too held this sort of respect to be a fundamental commitment, but given everything else in their present perspective that they could, compatibly with that, continue to affirm” (2015: 86). This latter passage suggests that Larmore should not admit that his view excludes anyone, since the relevant form of justifiability to persons is not, after all, internalist. Instead, it is a hybrid one, with a significant externalist element which subjugates the beliefs and values that it comes into conflict with.Footnote 14

Though this view may appear to occupy some middle ground, there is a significant risk of it simply collapsing into externalism. If the externalist element of the view dominates – as Larmore suggests that it does – by it excluding all beliefs and commitments in conflict with it, it is hard to see how the actual beliefs and commitments that people hold make any real difference. If justifiability can be achieved by asking what people would accept, on the counterfactual assumption that they held some other set of beliefs, then what beliefs they actually hold becomes irrelevant. The very same thing will be justifiable to them no matter what beliefs they hold, and hence the internalist element could be removed without it at all affecting what is in fact justifiable. The plausible conclusion to draw seems to be that the internalist element has no real function, and that this seemingly hybrid view would be hybrid in name only.Footnote 15

This does not rule out the possibility of a hybrid view. Perhaps such a view can be developed, but we have not yet seen a clearly worked out view of this kind. I shall thus put hybrid views aside, and confine my discussion to a comparison of internalism and externalism. The main reason for this being that internalism is clearly the currently dominant view.Footnote 16 My aim is to challenge this dominant view and to suggest a superior alternative, and that is a task that can be pursued without any attempts to address all possible interpretations of the idea of justifiability to persons. Also, I believe that we are in a better position to consider the possible merits of a view that attempts to occupy the middle ground, once we have better understanding of the relative merits of internalism and externalism. Hence, I shall now put this matter aside and instead go on to consider, and reject, one line of reasoning that may have led proponents of the Liberal Principle to prematurely reject the externalist view.

3 The Irrelevance of Stability

In we want to identify the most plausible version of the Liberal Principle, should we interpret the central notion of justifiability to persons along internalist or externalist lines? I strongly suspect that some proponents of the Liberal Principle would be inclined to reply that the answer is simple; it is only if we go for internalism that the Liberal Principle can help us solve the problem of stability. But as I shall here explain, considerations relating to stability will not settle this issue.

The idea that the Liberal Principle has a certain role in solving a particular problem of stability, or that it is its goal to do so, is a fairly common idea. Han van Wietmarschen, for instance, expresses this idea clearly when claiming that the principle “is meant to play a crucial role in an explanation of how a stable and just political society is possible despite profound and persistent disagreement” (2021: 354–355). An even clearer, and more developed, instance of this line of reasoning is found in the work of Quong. Quong explicitly states that the Liberal Principle has a certain goal. This goal he describes as showing “that the kind of citizens who would be raised in a society well-ordered by a liberal conception of justice could endorse and support their own liberal institutions and principles”, which would in turn show that liberalism “can generate its own support under ideal conditions and thus is not incoherent or unstable” (2011: 158).

Showing that a well-ordered liberal society could achieve stability in this way is, as Quong correctly points out, the overarching aim of Rawls’s political liberalism. In brief, the problem of stability that Rawls tried to solve with his political reformulation of his theory is the following. In Theory, Rawls had tried to demonstrate that the well-ordered society of justice as fairness could achieve inherent stability. This is the kind of stability brought about by just institutions themselves, by their tendency to generate the willing support of those living under them. In pursuit of demonstrating the possibility of inherent stability, Rawls argued that justice and the good are congruent. That is, that those living in a just society would view adhering to the demands of justice as congruent with their understanding of the good. This argument, however, depended on everyone accepting a certain Kantian conception of the good. This Rawls came to see as unsatisfactory, since he came to believe that just institutions would inevitably generate reasonable pluralism. That is, people living in a just society would come to hold different and incompatible conceptions of the good (1971: 255–57, 398, 572–75; 2005: xvi).Footnote 17

The main aim of Rawls’s Political Liberalism (2005) is thus to provide a new solution to the problem of stability; one which is compatible with pluralism about the good. Rawls therefore argues for the possibility of an overlapping consensus. Such a consensus occurs when persons who hold different conceptions of the good nevertheless affirm and support the very same conception of justice in the way required for inherent stability. Simply put: congruence is achieved in different ways for different persons, from the point of view of their respective conceptions of the good (2005: 11, 40).

Quong makes no effort to distinguish between political liberalism as such and the Liberal Principle. What he refers to as “the defining feature” of the former is clearly a version of the latter (2011: 138, 161). Consequently, he holds that it is the proper role of the Liberal Principle itself to somehow contribute to the main aim of political liberalism. The goal of the principle is, as he puts it, to show how inherent stability can be achieved under conditions of pluralism.Footnote 18 If you assume that this is the goal of the Liberal Principle, you may reach the conclusion that externalism is hopeless by the following line of reasoning. Inherent stability is something that is achieved from the point of view of persons who hold particular beliefs about their good. To show that inherent stability is possible, it must be shown that persons can, in the light of these beliefs of theirs, come to support just institutions in the right way. But externalism would have us disregard the beliefs and commitments that people hold, and justifiability to persons in the externalist sense will hence not ensure inherent stability. It seems, then, that internalism is necessary if the Liberal Principle is to successfully fulfil its role in solving the problem of stability.Footnote 19

Reasoning of this kind may be what has caused proponents of the Liberal Principle to disregard externalism. But this reasoning is misguided in at least two ways. First, it is not clear how an internalist construal of the Liberal Principle could contribute to solving the problem of stability. To see this, let us assume that showing that just institutions are justifiable in the internalist sense will also show that inherent stability is possible; if a particular set of institutions are justifiable to me in the internalist sense, this will also make it the case that I can be brought to support these institutions in the way required for inherent stability. Even if this is assumed, formulating the Liberal Principle in internalist terms appears completely superfluous. The only thing that we have then accomplished is to make an additional normative claim; we have said that not only will justifiability in the internalist sense show that inherent stability is possible, but that such justifiability is also necessary for political legitimacy. But clearly, this additional normative claim does not contribute to solving the problem of stability. Even without it, it will be the case that it can be shown that justifiability in the internalist sense makes inherent stability possible. If one aims to demonstrate the possibility of stability for the right reasons by way of justifiability in the internalist sense, bringing in political legitimacy is simply redundant.

Against this charge of redundancy, it might be pointed out that Rawls appears to hold that there is an important connection between stability and legitimacy. “Stable social cooperation”, he claims, “rests on the fact that most citizens accept the political order as legitimate” (2001: 125). If this is true, there is indeed some kind of connection between stability and legitimacy. But this is merely a connection regarding what people must believe in order for stability to be achieved, and what they must believe in order to achieve this end does not determine what is in fact required for legitimacy in the moral sense. These are simply different questions altogether.

This point brings me to the more fundamental mistake: the very assumption that the Liberal Principle must have a role in solving the problem of stability. That this assumption is mistaken is evident once we remind ourselves of the fundamental difference between the problem of political legitimacy and the problem of inherent stability. The former concerns the requirements for the instantiation of the normative property of legitimacy, and is therefore a normative problem. In contrast, the problem of inherent stability concerns the instantiation of a certain non-normative property, and is a completely different problem. Though Rawls refers to this form of stability as “stability for the right reasons”, this is merely a way of describing stability achieved in a certain way. It is the kind of stability achieved by institutions when “those taking part in these arrangements acquire the corresponding sense of justice and desire to do their part in maintaining them” (1971: 454). Hence “right reasons” merely refers to the sense of justice fostered by the institutions; this sets inherent stability apart from other kinds of stability in how it is brought about, but does not imply that the institutions actually are just, or that citizens have correct beliefs about what justice requires. We may of course have very good reasons to value achieving this kind of stability, but stability as such is nothing more than a descriptive fact about the relation between institutions and those living under them. In this it is similar to legitimacy in the descriptive sense, which consist in a certain kind of support for the government or the state; the instantiation of legitimacy in this sense is clearly the instantiation of a non-normative property, but it is a property that we may have very good reasons to value.

The point of this distinction between normative and non-normative properties is not meant to suggest that the problem of inherent stability is not a normatively important one. I merely want to emphasize that the problem of political legitimacy is clearly distinct from the problem of inherent stability, and that we lack good reasons to believe that a principle of legitimacy must be such that it contributes to solving other problems. The problem of political legitimacy is the normative problem of whether, and in virtue of what, a government may possess the right to rule. If a principle of political legitimacy can be said to have any role or goal at all, it should surely be to correctly solve this normative problem, and nothing more. Whether the correct solution to this problem will also in some way contribute to solving the distinct problem of stability is a completely open question. Therefore, it is hardly a consideration that can count against a version of the Liberal Principle that it will not be of any help in solving this problem; it may nevertheless provide the correct account of political legitimacy. Differently put: solving the problem of inherent stability is not a plausible adequacy condition for a principle of political legitimacy.

None of this amounts to an argument against the significance of the problem of stability. It does not in any way suggest that Rawls’s political reformulation of his theory was a mistake, and it does not show that a version of the Liberal Principle cannot in some way contribute to solving the problem of stability.Footnote 20 What it does suggest, however, is that we should avoid assuming that any version of the Liberal Principle should contribute to solving this problem. We should be careful to distinguish between stability and legitimacy, and avoid assuming that establishing inherent stability will simultaneously establish political legitimacy. I realize that this may strike some political liberals as an unwelcome result, as it makes their task more difficult. Not only do they need to worry about the kind of justifiability to citizens that can secure inherent stability, but also about the kind of justifiability that is necessary to secure legitimacy. But while this may make their task more difficult, it would strengthen rather than weaken their view if they were to clearly uphold the distinction between stability and legitimacy. Failing to adequately distinguish between two distinct philosophical problems can, in my view, only be detrimental to the project that they pursue.

The upshot of this discussion is that once we clearly distinguish between stability and legitimacy, considerations relating to solving the problem of stability appear highly unlikely to be decisive in the choice between internalism and externalism. We should therefore look elsewhere, in order to determine the matter.

4 Freedom and Equality

In order to decide between internalism and externalism, we should consider what motivates the requirement of justifiability to persons in the first place. A very plausible suggestion, which is the one I shall here pursue, is that justifiability to persons is motivated by their moral status as free and equal.

Appeals to the freedom and equality of persons are common in the literature on liberal legitimacy. Quong claims that we “honour the idea of persons as free and equal by supposing that one cannot rightly wield power over another unless they can justify the exercise of that power to the person over whom it is exercised” (2011: 2). Similarly, Kevin Vallier holds that unless state coercion is “based on principles and ideas that all can reasonably accept” it will be “incompatible with our understanding of ourselves as free and equal” (2019: 213). And Paul Weithman explicates the fundamental idea underlying the Liberal Principle as the claim that the “exercise of political power must be consistent with citizens’ freedom and equality” (2019: 56).

The basic idea expressed in these statements may be formulated as follows. Persons are, in a fundamental moral sense, free and equal. The exercise of political power is only legitimate if it treats everyone over whom it is exercised as free and equal, and it treats them in that way only if it is justifiable to them. If this is the basic idea that underlies the Liberal Principle, the proper kind of justifiability is the one that fits with treating persons as free and equal. This, in turn, will depend on how, exactly, this freedom and equality of persons should be understood.

4.1 Freedom as Individual Authority

One way to arrive at an interpretation of the freedom and equality of persons that supports internalism is by a particular understanding of the idea, expressed by Rawls in his early writings, that “free persons […] have no authority over one another” (1999: 59). We may understand this idea of no authority as implying a far-reaching individual authority. If free persons are not under the authority of others, then the only authority with regard to how they are to act and live is, it may be thought, the individuals themselves. Free persons are thus, to a considerable extent, free to live in accordance with how they themselves believe they ought to live.

This way of reasoning is perhaps most clearly expressed in the work of Gerald Gaus. On Gaus’s view, to treat a person as free is to “acknowledge that her reason is the judge of the demands morality makes on her” (2011: 15). The idea is not, of course, that a free person is free to determine what morality demands of her. But as free, and not under the authority of anyone else, she is free with regard to what other persons believe that these demands are. Others may not force her to live in accordance with their views on this matter, precisely because they lack the authority to do so. Free and equal persons are thus, as Gaus puts it, “equal interpreters of morality” (2011: 17). They are equals in the project of determining how they ought to live, in virtue of being equally in possession of individual authority.

It could, quite plausibly, be thought that everyone is being treated as an equal, with no one having a greater authority than the others, in a well-functioning democratic society (Kolodny 2016: 65–66). But on Gaus’s view, that is not the case. If a majority were to force (with democratic means) their views on a dissenting minority, that would be “to manifest disrespect for them as equal interpreters of morality” (2011, 17). The individual authority possessed by a free person thus acts as a kind of veto on how she is treated by others. Such a strong notion of individual authority is clearly not realized by the equal authority shared by citizens in a democratic society.

It should come as no surprise that this view leads Gaus to an internalist interpretation of the requirement of justifiability to persons. In order to treat others as free and equal in this sense, we cannot exercise political power over them unless this exercise is justifiable to them from their particular perspectives. This does not mean that they need to actually consent to what we do. But what is justifiable to them in the sense required to treat them as free is significantly constrained by their beliefs and commitments, and what is accessible to them by exercising their powers of reasoning (2011: 250).Footnote 21

Views very similar to this have been expressed by others as well, though put in somewhat different terms. Vallier, for instance, appeals to the value of individual integrity. The integrity of free and equal persons implies that they have a strong interest to live in accordance with their “own projects and principles”, which requires justifiability to them in the internalist sense (2014: 86–87). Steven Wall formulates a similar idea in terms of respect for rational agency. It is in order to respect this rational capacity of persons that we need to treat them “in ways that they can see to be justified” (2016: 222).Footnote 22

Though there are differences between these views, they share the idea that free persons have a far-reaching individual authority to determine how to live. Since they have such an authority, the exercise of political power over them must be such that they themselves can come to see it as justified or acceptable. In other words: it must be justifiable to them in the internalist sense if they are to be treated as free and equal.

4.2 Rawlsian Freedom and Equality

In Rawls’s work we find an account of the freedom and equality of persons that differs significantly from the one presented above. And importantly, it is an account that supports externalism, rather than internalism. This account can therefore, I shall argue, provide a foundation for my suggested interpretation of the Liberal Principle. However, one caveat is in order. Rawls’s view is a complex one, and I shall here not attempt to capture it in full. For my purposes it is enough to describe some of its most central features, and explain how it differs from the view described above.

As previously noted, Rawls holds that free and equal persons have no authority over one another. But rather than understanding this as implying a far-reaching individual authority, Rawls conceives of it as implying a certain kind of equal authority. Persons who have no authority over one another are equals in the sense that they have “a right to equal respect and consideration in determining the principles by which the basic structure of their society is to be regulated” (1999: 233). But this reference to determining the principles that are to regulate their society is not, of course, a reference to an actual process of decision making. Instead, this equal respect and consideration requires that one be equally represented in the process that Rawls holds is to determine principles of justice; that is, the hypothetical original position.

The idea of free and equal persons is therefore, in combination with the idea of society as a fair system of cooperation, what determines (to a significant extent, at least) the description of the original position. Indeed, the function of the original position can be described as correctly capturing these fundamental ideas, in order to yield the principles that best coheres with them (Rawls 1971: 13; 1999: 236–37; 2005: 22). The idea that persons are equals – and that they have an equal authority – motivates that the parties in the original position are symmetrically situated, and each given an equal say. It also serves as a rationale for the veil of ignorance, since describing the parties as equals requires that factors such as level of wealth and position in society be granted no influence on what is decided (Rawls 1971: 18–19; 2005: 24–25).

Turning now to freedom, Rawls holds that there are several aspects in which persons are free. Of these, one is especially important here.Footnote 23 This concerns how persons are free in relation to the particular conceptions of the good that they hold. Rawls assumes that persons have, at any given time, a determinate conception of the good. That is, they have an idea of what they value in life which shapes their plans and aims. But as free, they are not to be considered as “inevitably tied to” a certain conception of this kind (2005: 30). This aspect of the freedom of persons implies, first, a freedom to select what ends to pursue, and to change those ends at any time. But this freedom with regard to the conception of the good that one affirms is circumscribed. It only amounts to freedom within the limits set by the principles selected in the original position. Some people may have ideas of the good the pursuit of which would conflict with these principles of right. But even though they are free, they are not free to pursue these ends. This is what Rawls refers to as the “priority of the right over the good” (1971: 31; 2005: 449).

Secondly, and more fundamentally, this aspect of freedom means that the moral status of persons, and the nature and strength of their claims on others, are not in any way affected by the particular conception of the good that they hold at some given time (Rawls 1999: 255, 331, 404–5; 2005: 30). In this sense, persons are free in relation to the particular conception of the good that they hold at any given time. More concretely, this aspect of the freedom of persons means that information about the particular conceptions of the good that people affirm must be hidden behind the veil of ignorance. To instead include this information would not only make it the case that the parties could try to select principles tailored to serve their interests on the expense of others; it would be a failure to represent persons as free.

The rival view presented in the previous section fails to treat persons as free in this respect. On this view, what determines how we may treat others is what is justifiable to them on the basis of the beliefs that they happen to hold. This makes it the case that how we may treat others will, to a significant extent, depend on the conceptions of the good that they happen to affirm. But this, according to the Rawlsian view, is a manifest failure to treat others as free. This follows from the idea that as free, the nature and strength of our claims on others does not depend on the particular beliefs and aims that we may have at any given time. Hence internalism is incompatible with this account of the freedom of persons.

This brief exposition should suffice to demonstrate the extensive differences between these two interpretations of the freedom and equality of persons. On the view favoured by Gaus and others, the lack of authority over others implies a far-reaching individual authority. This makes it the case that how we may treat others, and what is justifiable to them, depends on what they believe, and what their reason can lead them to acknowledge. The Rawlsian view, on the other hand, instead interprets the lack of authority as implying an equal authority. Therefore, the freedom and equality of persons does not in any way imply that they are free to live in accordance with their own understandings of the demands of morality. Rather, to be treated as free and equal persons we are to be treated in accordance with the principle that best coheres with this moral status of ours. That is, the principles that would be selected in the original position.

In Theory, this view is clearly expressed by Rawls in his dismissal of the idea that we ought to be free “to form our moral opinions, and that the conscientious judgment of every moral agent ought absolutely to be respected” (1971: 518). This view is, Rawls contends, mistaken. It is not the case that we are to respect the conscientious judgments of individuals. We are instead to respect a dissenting person “as a person and we do so by limiting his actions […] only as the principles we would both acknowledge permit” (1971: 519). These principles are the principles that would be selected in the original position. Hence it is does not matter whether persons are able, from their particular perspectives, to validate these principles by their own reason; they are treated as free and equal even if they themselves are not in a position to appreciate this fact.

4.3 Justifiability to Persons as Free and Equal

On Rawls’s way of formulating the Liberal Principle, it requires that the exercise of political power is such that “all citizens as free and equal may reasonably be expected to endorse” it (2005: 137, my emphasis).Footnote 24 What I want to suggest is the following. We should take this as implying the view that what is justifiable to all is what they could accept as free and equal. Further, this reference to persons as free and equal should be understood as a reference to the Rawlsian account of freedom and equality presented above; and if it is understood in that way, we are quite naturally led to an externalist interpretation of the Liberal Principle.

The internalist interpretation follows from an account of the freedom and equality of persons according to which they have a far-reaching individual authority to determine how to live. But as we have seen, the Rawlsian account does not involve anything close to that kind of individual authority. Instead, it implies that we are treated as free and equal when we are treated in accordance with the principles selected in the original position. In line with this, it can quite plausibly be claimed that what is justifiable to us as free and equal is determined in the same way.

In fact, this view is suggested by Rawls in at least one, seldomly noted, passage in his Political Liberalism.Footnote 25 In this passage he discusses political legitimacy and how we are to identify what “other citizens (who are also free and equal) may reasonably be expected to endorse along with us”. His suggestion, he says, is “the values expressed by the principles and guidelines that would be agreed to in the original position” (2005: 226–27). This is a suggestion which is exceedingly difficult to combine with the dominant internalist interpretation, since the fact that something would be selected in the original position does very little to show that it is justifiable to everyone in the internalist sense. It is both possible and highly expected that there will be some to whom the results of the hypothetical contract are not justifiable; no matter how much they would reason about the matter, they would not be able to see the resulting principles as justified or even acceptable.

To further elaborate how hopeless this suggestion appears if we assume the correctness of internalism, consider the information excluded by the veil of ignorance. This feature of the original position excludes information about the persons that the parties represent in such a way that there is nothing that sets them apart from each other behind the veil. This effectively ensures that what internalism holds to be of central importance for what is justifiable to a person – what the person believes and values, and hence what distinguishes her particular perspective from that of others – has no impact whatsoever on what is justifiable to her. For instance, the fact that one person holds a specific conception of the good that differs from that of others does not make a difference in terms of what is justifiable to her.

But Rawls’s suggestion makes perfect sense in the light of his view on the relation between the original position and the idea of persons as free and equal. And it is easy to combine with the Liberal Principle, once we recognize that externalism is a viable option. Just as in the case of Scanlon’s externalist view, what is justifiable to us in the relevant sense does not depend on our personal characteristics, or the specifics of our individual perspectives. Instead it depends on a moral notion of reasonableness, which on Rawls’s view is modelled by the various constraints imposed on the parties in the original position (2005: 305). Since we are being represented as free and equal in this hypothetical situation, and as fairly situated with regard to each other, we can reasonably (in the moral sense) be expected to endorse the outcome of it. In this externalist sense we could accept it, irrespective of whether we in fact will do so, or if we are able to do so on the basis of our beliefs and commitments. We could accept it as free and equal, and what we could accept as such is what determines what is justifiable to us.

5 Avoiding Exclusion

We have seen that the Rawlsian account of freedom and equality is incompatible with internalism about justifiability to persons, and that it instead suggests an externalist reinterpretation of the Liberal Principle. But my aims in this paper are not, as I emphasized in the introduction, primarily exegetical. What matters the most is not which interpretation of the Liberal Principle is the best interpretation of Rawls’s views, but rather which is the philosophically most plausible one. I therefore want to argue, without committing myself to a specific externalist version of the Liberal Principle, that adopting externalism will have significant consequences for how this view of liberal legitimacy should be understood. I shall here explain one such consequence, which suggest that externalism has a considerable advantage compared to internalism.

As formulated in the introduction above, The Liberal Principle requires justifiability to all citizens. But in fact, most advocates of the principle hold a view according to which the notion of “all citizens” is significantly qualified. Strictly speaking, it is only to the “reasonable” (or “qualified”) to whom justifiability is required (Estlund 2008: 4; Quong 2011: 290; 2018; Lister 2013: 8–9, 127; Bajaj 2017: 3135). Different philosophers define the reasonable in different ways, but the general idea is that qualifying as reasonable requires, at the very least, that one holds certain moral beliefs.Footnote 26 Those who do not hold these beliefs are classified as “unreasonable” (or “unqualified”), and political legitimacy does not require justifiability to them.

This significant qualification of the view – one that may be labelled exclusionary, due to the exclusion of the unreasonable – is an unfortunate one. Part of the intuitive appeal of the Liberal Principle is surely that it makes the legitimacy of the exercise of political power dependent on justifiability to all those who are directly subjected to it. But those deemed unreasonable are no less subjected to it than those who qualify as reasonable. Furthermore, this qualification of the view appears especially difficult to accept on the assumption that it is the idea of persons as free and equal that provides the rationale for the requirement of justifiability. As Enoch has argued, surely the unreasonable are also free and equal in the fundamental moral sense (2015: 120–23). But if so, we should treat the unreasonable as well, and not only those who are reasonable, as free and equal by exercising political power over them only in ways that is justifiable to them.

I suggest that the exclusionary interpretation of the Liberal Principle be understood as a consequence of internalism. If we consider the reasons put forward in favour of qualifying the principle so that it only requires justifiability to reasonable persons, we find that it is motivated by the worry that the existence of persons with sufficiently illiberal beliefs will render liberal institutions illegitimate. David Estlund, for instance, worries about those who are “crazy or vicious”. If we were to demand justifiability to them as well, it would “be hard to find much legitimate authority” (2008: 4). Similarly, Quong believes that trying to show that liberal institutions are justifiable to everyone – the liberal and the illiberal alike – would be “an attempt to do the impossible” (2011: 140).

The reason as to why certain persons are identified as obstacles to the legitimacy of liberal institutions is, it is plain, the beliefs that these persons hold. It is precisely because the illiberal hold illiberal beliefs that liberal institutions are believed to be impossible to justify to them. This clearly suggests that the problem is caused by an internalist interpretation of what justifiability to persons consists in. Since internalism construes justifiability to persons in such a way that it is relative to their beliefs, sufficiently illiberal beliefs will result in the illegitimacy of liberal institutions. Without exclusion of the unreasonable, internalism thus threatens to lead to anarchical or at least libertarian implications.Footnote 27

Differently put, the present point is this. Internalism places no moral constraints on what is justifiable to persons. Hence if what I believe is sufficiently immoral, then what is justifiable to me in the internalist sense will most likely not be reasonable in a moral sense. What is justifiable to the righteous may be morally exemplary, while what is justifiable to the wicked will most likely be morally unacceptable. Hence if an internalist version of the Liberal Principle is to have plausible implications, moral constraints must be incorporated in some other way. One way to incorporate such constraints is – as proponents of the exclusionary interpretation propose – to ensure that we only require justifiability to persons with acceptable moral beliefs. In this way exclusion functions as a corrective to what would otherwise be unacceptable implications of internalism.

Exclusion is thus a consequence of internalism. But if we instead adopt externalism, there is no need to qualify the Liberal Principle so that it only requires justifiability to the reasonable. Since externalism does not make justifiability to persons dependent on what they happen to believe and value, the problem that animates the exclusionary interpretation does not even arise in the first place. What is justifiable to the crazy or vicious, and the illiberal, is not dependent on their crazy, vicious, and illiberal beliefs. There is thus no need to exclude them from the group of persons to whom justifiability is owed. Hence externalism makes it possible to retain the appealing idea that legitimacy is dependent on justifiability to all those over whom political power is being exercised. We can thus have an inclusive account of liberal legitimacy. This I consider to be a significant advantage of the reinterpretation of the Liberal Principle that I have here suggested.

Internalism thus comes with considerable costs, which externalism allows us to avoid. But proponents of internalism could perhaps respond by claiming that externalism comes with considerable costs as well. In particular, they could claim that externalism fits poorly with how we are inclined to think about justification to others. On the internalist view, it may be suggested, it is clear how justifiability to persons is justifiability to them; to particular real persons, as they more or less are. But on the externalist view this connection to real persons, and how they differ from each other, is severed. Justifiability thus becomes justifiability to no one in particular, instead of justifiability to specific persons. This, it may be thought, is an account alien to how the idea of justifiability to persons is most naturally spelled out.

I highly doubt that the externalist view is really such a revisionary account of justifiability to others. To the contrary, I believe that we find this notion of justifiability to others in the influential theories of Scanlon and Rawls, and that it offers a quite natural and attractive way of spelling out this idea. But even if I am wrong about that, and it turns out to be revisionary, that does not appear to be a hard bullet to bite. Surely, the fact that the externalist account is more difficult to reconcile with our pretheoretical understanding of justifiability to persons (if there even is such a thing) is not as serious a drawback as the failure to treat everyone, and not only the reasonable, as free and equal. This is especially the case if it is this moral status of persons that provides the rationale for the requirement of justifiability to persons in the first place. That background makes it considerably more difficult, and more costly, to accept a view that fails to treat everyone as free and equal, than it is to accept a view that is somewhat more difficult to combine with how we are used to think about justifiability to others. I thus suggest, though I recognize that significantly more needs to be said in support of this conclusion, that adopting a revisionary account of justifiability to persons is a small cost to pay to better account for how we are to treat persons in order to treat them as free and equal.

6 Concluding Remarks

In this paper I have suggested a reinterpretation of the Liberal Principle that involves a significant departure from how it is usually understood. Though I have not attempted to demonstrate that this is the interpretation that best coheres with Rawls’s view as whole, I believe that the externalist version of the principle is supported by the Rawlsian account of the freedom and equality of persons. This, in combination with the considerable intuitive appeal of an inclusive account of to whom justifiability is owed, give proponents of the Liberal Principle good reasons to favour externalism over internalism.

However, I do not claim that this case for externalism is in any way conclusive. A complete assessment of how to best conceive of justifiability to persons requires consideration of a host of other issues that I have not been able to address here. One important question is whether my suggestion can adequately account for reasonable pluralism. Proponents of the Liberal Principle typically hold that this kind of pluralism ought to have a significant impact on what is justifiable to all, and it might be thought that externalism rules this out. Whether this is so depends on what kind of pluralism that we should be concerned to accommodate in a theory of political legitimacy, as well as how we should do so. My own view is that it is primarily pluralism about the good, not about the right, that we should accommodate, and externalism has no problems with achieving that. It may also, I believe, be able to accommodate some disagreement about the right, but only within a quite limited range.Footnote 28 Though I have not been able to explore these issues here, they must certainly be addressed if the case for externalism is to be made more complete.

Another area of further inquiry regards a more thorough evaluation of the competing accounts of freedom and equality. Though I find the Rawlsian view that I have here described to be a highly plausible one, more certainly needs to be said in support of it. In addition, there might be those who think that the grounds for the requirement of justifiability to persons is to be located elsewhere. For instance, it has been suggested that it is respect for persons that is the underlying value. Footnote 29 Those who find that view plausible will most likely wonder whether my view can accommodate the importance of respect. Others might wonder how it fares with regard to other important values, such as reciprocity and civic friendship.

Interesting and important as these questions may be, addressing them is a task that must be left to another occasion. What I have tried to do here is to challenge internalism, and to demonstrate that externalism is a view to be taken seriously by those who find the Liberal Principle appealing as an account of political legitimacy. Hence, I do not claim that the arguments here provided settles the matter of how to best understand the Liberal Principle. But I do claim that they show, at the very least, that construing justifiability to persons in externalist terms merits considerably more attention than it has hitherto received.Footnote 30

Availability of Data and Material

Not applicable.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Notes

There are different ways of understanding this right to rule, and different accounts of the normative significance of political legitimacy. With regard to the question of what the right to rule consists in, there is disagreement on whether this right correlates with a duty to obey the commands of the government. Some claim that the right to rule entails no such duty, while others hold that it does. Regarding the issue of normative significance, some appear to equate legitimacy with what is morally justified all things considered, while others see legitimacy as merely one among many normative considerations that contribute to determining whether something is morally justified or not. For different views on both of these issues, see for instance Buchanan (2004: 233, 239) and Simmons (2001: 130, 136). I believe that the right to rule need not correlate with a duty to obey, and that a legitimate government need not be morally justified all things considered. But the arguments that I provide in this paper are compatible with different views on these matters, and hence I shall not discuss them any further.

Throughout this paper I will use “the Liberal Principle”, and sometimes “liberal legitimacy”, to refer to this principle. For Rawls’s different formulations of the Liberal Principle, see (1999: 490; 2001: 41, 141, 202; 2005: 137, 217). See also Sect. 4.3 below.

The Liberal Principle thus applies to the exercise of political power in a general sense, including who rules as well as how it is done. With regard to the question of who has the right to rule, Rawls’s view is that governmental legitimacy depends on “the general structure of authority” being justifiable to all citizens (2005: 393). Since this general structure can be justifiable even if the government performs an action that is not, the Liberal Principle does not entail the implausibly strong view that governmental legitimacy requires that each and every action performed by the government is a legitimate one.

I say “almost” since there are some rare exceptions. See the end of Sect. 2.1 and footnote 25 below.

In order to avoid misconceptions, it may be noted that this form of independence concerns only the standard of justifiability to persons internal to the Liberal Principle. Other forms of dependence may thus be fully compatible with externalism of this kind. For instance, take the meta-ethical view that moral truth somehow depends on the beliefs and attitudes of people. An externalist account of justifiability to persons may clearly be rendered true in that way without ceasing to be externalist in the relevant sense.

Some may worry that externalism renders the notion of justifiability to persons redundant, and that it may just as well be expressed in terms of what is simply morally justified. This redundancy objection has been discussed, and convincingly responded to, by Ridge (2001) and Suikkanen (2005). In brief, Scanlon’s view is not vulnerable to this charge due to the fact that the reasons for rejecting a principle must be personal, or agent-relative. This makes it the case that what is reasonably rejectable is not simply a function of what is morally right independently of justifiability to persons. If suitably constructed, other versions of externalism will be similarly invulnerable to charges of this kind.

Some proponents of the Liberal Principle, most notably Gaus (2011) and Vallier (2014; 2019) are prepared to accept something quite close to libertarianism, or at least classical liberalism. As a consequence, there is no need for them to limit the requirement of justifiability to the reasonable only. But Gaus and Vallier endorses a view that radically departs from the view of Rawlsians, to whom implications of this kind are utterly unacceptable. Hence the discussion on internalism and the exclusion of the unreasonable in Sect. 5 below applies primarily to Rawlsians (and others with similar egalitarian commitments) who aims for a version of the Liberal Principle that is compatible with their views on what justice requires.

I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for The Journal of Ethics for suggesting this interpretation of Quong’s view, and for stressing the importance of addressing it.

This description of Quong’s project – one that may at first glance seem rather peculiar – is explained further in Sect. 3 below. In short, it is explained by the fact that he makes no sharp distinction between legitimacy and stability, and holds that the function of the Liberal Principle is to show how a well-ordered liberal society can be rendered stable by justifiability in the internalist sense.

For some additional support of this interpretation, consider Quong’s claim that “rules prohibiting murder and rape do not need to be justifiable to […] everyone, including those persons who sincerely wish to engage in these actions and would prefer that such actions be permissible” (2018). This is the exact opposite of what we should expect him to say if he was a proponent of the view that what is justifiable to a person is determined by what is justifiable to hypothetical reasonable persons. He would then instead be able to say that rules prohibiting murder and rape are justifiable even to those who sincerely wish to engage in these activities, on the grounds that these prohibitions are justifiable to reasonable hypothetical persons. That he does not say that is, I submit, clear evidence for him using the notion of justifiability to persons in the internalist sense.

Another possible statement of a hybrid view is found in Wietmarschen (2021: 355). Though what he says could perhaps also be interpreted as an expression of externalism.

Does this mean that Larmore is actually an externalist? I highly doubt that. Because if he were, there would be no reason for him to admit that his view excludes anyone. In that light his apparent externalist claims appears as somewhat of an afterthought, and perhaps not fully incorporated into his view.

For additional support of the claim that internalism is indeed the dominant view in the literature, see Sect. 5 below.

Quong’s position is not, it should be emphasized, that it is by citizens accepting the Liberal Principle itself that the principle contributes to inherent stability. That view would leave it entirely open whether the principle should be internalist or externalist, as there is nothing that rules out that an externalist version of it could be accepted by citizens in the required way. Quong’s view is different, in that he holds that the principle is to show, by way of its account of justifiability to all, how inherent stability is possible.

Indeed, that it can do so is suggested by Weithman, who has argued that the Liberal Principle is necessary for Rawls in order to handle difficult cases where some citizens’ religious conceptions of the good would lead them to view certain actions as unjust. The Liberal Principle supplies a standard for political justification which may lead these citizens to view such laws as justified, even though they see them as unjust. This, in Weithman’s view, is an essential part of Rawls’s solution to the problem of stability (2015: 98–100). This is of course completely compatible with what I argue here.

For the other aspects, see Rawls (2005: 32–34).

For some additional examples of the Liberal Principle formulated in similar terms, see Rawls (2001: 141; 2005: 393).

Someone who does note this passage is Weithman. He is also the only one whom I know of who has suggested a reading of Rawls’s principle of political legitimacy similar to the one presented here (2019: 58).

For an example of an account of the relevant beliefs, see Quong (2011: 143–144).

This threat of anarchism is noted by Enoch (2015).

I discuss these topics in Andersson (2019).

Previous versions of this paper have been presented at the Higher Seminar of Practical Philosophy at the Department of Philosophy, Uppsala University, April 2021, and at the Stockholm June Workshop in Philosophy 2019: Morality and Modality, Stockholm University. I am grateful to all the participants for their helpful comments and suggestions. Special thanks to Folke Tersman, Jens Johansson, Kasper Lippert-Rasmussen, and Per Algander. Financial support from the Swedish Research Council (grant 2020-06502) is gratefully acknowledged..

References

Andersson, Emil. 2019. Reinterpreting Liberal Legitimacy. Doctoral dissertation, Uppsala University, Uppsala, Sweden.

Bajaj, Sameer. 2017. Self-Defeat and the Foundations of Public Reason. Philosophical Studies 174(12): 3133–3151.

Buchanan, Allen. 2004. Justice, Legitimacy, and Self-Determination. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Enoch, David. 2013. The Disorder of Public Reason. Ethics 124(1): 141–176.

Enoch, David. 2015. Against Public Reason. In Oxford Studies in Political Philosophy, Volume 1, eds. David Sobel, Peter Vallentyne, and Steven Wall, 113–140. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Estlund, David. 2008. Democratic Authority. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Freeman, Samuel Richard. 2007. Rawls. London: Routledge.

Gaus, Gerald F. 2011. The Order of Public Reason. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Kolodny, Niko. 2016. Political Rule and Its Discontents. In Oxford Studies in Political Philosophy, Volume 2, eds. David Sobel, Peter Vallentyne, and Steven Wall, 35–68. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kumar, Rahul. 2009. Wronging Future People: A Contractualist Proposal. In Intergenerational Justice, eds. Axel Gosseries and Lukas H. Meyer, 251–272. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Larmore, Charles. 2008. The Autonomy of Morality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Larmore, Charles. 2015. Political Liberalism: Its Motivations and Goals. In Oxford Studies in Political Philosophy, Volume 1, eds. David Sobel, Peter Vallentyne, and Steven Wall, 63–88. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lister, Andrew. 2013. Public Reason and Political Community. London: Bloomsbury.

Quong, Jonathan. 2011. Liberalism without Perfection. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quong, Jonathan. 2018. Public Reason. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2018 Edition), ed. Edward N. Zalta. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/public-reason/.

Rawls, John. 1971. A Theory of Justice. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, John. 1999. Collected Papers, ed. Samuel Richard Freeman. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, John. 2001. Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, ed. Erin Kelly. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Rawls, John. 2005. Political Liberalism (Expanded Edition). New York: Columbia University Press.

Ridge, Michael. 2001. Saving Scanlon: Contractualism and Agent-Relativity. Journal of Political Philosophy 9(4): 472–481.

Scanlon, T. M. 1998. What We Owe to Each Other. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap.

Schoelandt, Chad Van. 2015. Justification, Coercion, and the Place of Public Reason. Philosophical Studies 172(4): 1031–1050.

Simmons, A., and John. 2001. Justification and Legitimacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Suikkanen, Jussi. 2005. Contractualist Replies to the Redundancy Objections. Theoria 71(1): 38–58.

Vallier, Kevin. 2014. Liberal Politics and Public Faith: Beyond Separation. New York: Routledge.

Vallier, Kevin. 2019. Political Liberalism and the Radical Consequences of Justice Pluralism. Journal of Social Philosophy 50(2): 212–231.

Wall, Steven. 2002. Is Public Justification Self-Defeating? American Philosophical Quarterly 39(4): 385–394.

Wall, Steven. 2013. Public Reason and Moral Authoritarianism. Philosophical Quarterly 63(250): 160–169.

Wall, Steven. 2016. The Pure Theory of Public Justification. Social Philosophy and Policy 32(2): 204–226.

Weithman, Paul J. 2010. Why Political Liberalism?: On John Rawls’s Political Turn. New York: Oxford University Press.

Weithman, Paul J. 2015. Legitimacy and the Project of Political Liberalism. In Rawls’s Political Liberalism, eds. Thom Brooks and Martha Nussbaum, 73–112. New York: Columbia University Press.

Weithman, Paul J. 2019. Another Voluntarism: John Rawls on Political Legitimacy. In Legitimacy: The State and Beyond, eds. Wojciech Sadurski, Michael Sevel, and Kevin Walton, 43–65. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wendt, Fabian. 2019. Rescuing Public Justification from Public Reason Liberalism. In Oxford Studies in Political Philosophy, Volume 5, eds. David Sobel, Peter Vallentyne, and Steven Wall, 39–64. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wietmarschen, Han van. 2021. Political Liberalism and Respect. Journal of Political Philosophy 29(3): 353–374.

Funding

Swedish Research Council, grant number 2020-06502. Open access funding provided by Uppsala University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All work is made by the author.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The author has no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Andersson, E. Freedom, Equality, and Justifiability to All: Reinterpreting Liberal Legitimacy. J Ethics 26, 591–612 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10892-022-09406-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10892-022-09406-5