Abstract

During the medieval and early modern periods the Middle East lost its economic advantage relative to the West. Recent explanations of this historical phenomenon—called the Long Divergence—focus on these regions’ distinct political economy choices regarding religious legitimacy and limited governance. We study these features in a political economy model of the interactions between rulers, secular and clerical elites, and civil society. The model induces a joint evolution of culture and political institutions converging to one of two distinct stationary states: a religious and a secular regime. We then map qualitatively parameters and initial conditions characterizing the West and the Middle East into the implied model dynamics to show that they are consistent with the Long Divergence as well as with several key stylized political and economic facts. Most notably, this mapping suggests non-monotonic political economy dynamics in both regions, in terms of legitimacy and limited governance, which indeed characterize their history.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Note that the timing of the reversal of fortunes cannot be inferred from this figure. First of all, pre-modern population data are subject to significant measurement error, perhaps mis-dating the precise point of reversal by centuries. Second, urban population is just one of many metrics social scientists employ as an indicator of socio-economic development. Levels of trade, science, technology, and architecture almost certainly diverged at different times.

We focus our explanatory analysis of the Long Divergence on historical forces that arose when the divergence took place during the medieval and early modern periods. Arguably, and importantly, these forces act upon—and interact with—more deeply-rooted dynamics at a slower frequency, like those stressed in Galor and Moav (2002); Ashraf and Galor (2013); Galor and Özak (2016); Bockstette et al. (2002) and Galor (2022). Our analysis hence necessarily relies on a sort of adiabatic assumption that the political economy and cultural processes we study are rapid enough to be the ones which mostly matter at the time-scale under consideration.

More precisely, we focus on the period starting from the end of the Western Roman Empire in the West and the emergence of the Umayyad Caliphate in the Middle East until the onset of the Reformation in Europe and the capture of the Egyptian Mamluk Empire by the Ottoman Empire. Beginning the historical narratives from the end of the Roman Empire in the West and the Umayyad Caliphate in the Middle East is appropriate because both represent “initial conditions” far from either a secular or a religious stationary state.

Christianity was born in the Roman Empire, and its followers were a persecuted minority. It was hence in no position to legitimate the emperor. Meanwhile, Islam formed conterminously with an expanding empire, and numerous important Islamic dictates specify the righteousness of following leaders who act in accordance with Islam (Hallaq, 2005; Rubin, 2011, 2017) There is a historical literature, discussed further in Sect. 4.2, which disputes how much early Islamic empires, especially the Umayyad Empire (661–750), relied on religious legitimacy. For the time being, we note the distinction between the exogenous legitimating technology and its endogenous use by the state. Our model attempts to understand the latter conditional on the former, and in fact predicts that early Islamic empires should have initially sought to reduce reliance on religious legitimacy despite the relatively high (exogenous) capacity of Muslim religious authorities to legitimate rule.

In the Appendix in supplementary file, we further extend the model to consider the role of religion and religious legitimacy in inhibiting innovation and technological change (Mokyr, 1990, 2010, 2016; White, 1972, 1978; Davids, 2013; Bénabou et al., 2015, 2020; Coşgel et al., 2012; Squicciarini, 2020) More generally, it is certainly not the case that religion as a whole always has a negative impact on economic development; see Barro and McCleary (2003) and McCleary and Barro (2019) for an overview of the literature and a theory of the positive associations between religion and economic development.

In Sect. 5 we extend the model to study the equilibrium relationship between religious legitimacy and limited governance.

The study of political legitimacy has a long history in the social sciences. Perhaps most famously, Weber (1947) defined political legitimacy as either charismatic, traditional, or legal-rational. Our definition follows more closely in the footsteps of the definition of political legitimacy employed by Lipset (1959, p. 86): “the capacity of a political system to engender and maintain the belief that existing political institutions are the most appropriate or proper ones for the society.” For similar definitions of political legitimacy, see Hurd (1999), Tyler (2006), Gilley (2006), Levi et al. (2009), Greif and Tadelis (2010), Rubin (2017), and Greif and Rubin (2023a, 2023b). More specifically, in our context, see also Lewis (1974, 2002); Rubin (2011); Platteau (2017); Auriol and Platteau (2017); Auriol et al. (2022); Coşgel et al. (2012); Coşgel and Miceli (2009), and Kuru (2019). In our context, legitimacy takes the form of a religious justification, provided by religious elites, supporting the ruler’s right to rule and have her demands obeyed (Greif & Rubin, 2023b)

This is in line with the conceptualization of institutional change proposed in Greif and Laitin (2004) and Greif (2006), in which institutions are exogenous to the players at any given point in time but evolve over time in response to the actions taken by the players at that time in response to institutional and cultural incentives. A fully forward-looking model of institutional change is analytically intractable when joined with cultural dynamics; see Bisin and Verdier (2017) for a discussion and Lagunoff (2009) and Acemoglu et al. (2015) for forward-looking institutional change. Some historical motivation for myopic institutional change in the study of the emergence of democracy is found in Treisman (2020).

These costs are assumed to be increasing in \(m_{t}\) and sufficiently convex to satisfy a regularity condition, needed to ensure that when religious clerics have a high political weight \(\lambda _{t}\), the policy problem associated with institutional design is well behaved and provides a finite equilibrium provision of m.

This is just one of the several dimensions of the ruler’s governance ability which are affected by legitimacy. Importantly, for instance, legitimacy lowers the likelihood of revolt (Gill, 1998; Hurd, 1999; Gilley, 2008; Guo, 2003; Tyler, 2006; Hechter, 2009; Chaney, 2013; Bentzen & Gokmen, 2022; Greif & Rubin, 2023a, b)

These are the types of proscriptions that typically have the largest effect on economic growth. We are not concerned with other types of prohibitions that only affect religious believers, such as certain dietary restrictions or marriage or divorce restrictions (Tolan, 2019; Freidenreich, 2013, 2015) The model could be amended to allow secular individuals to be less affected than religious individuals by the cost of religious proscriptions. In such a case, it can be shown that this increases the likelihood of a long-run theocratic state compared to a secular state. See footnote 26 for a discussion.

The parameter \(\phi\) is held as exogenous in the model, even though there are clearly endogenous elements of religious proscriptions (Rubin, 2011; Seror, 2018) In fact, both Islamic law and Christian (canon) law changed over time to address economic exigencies (Noonan, 1957, 2005; Berman, 1983; Hallaq, 1984, 2005). Nonetheless, note that the effective cost of economically-inhibitive religious proscriptions \(c(\alpha _{c,t})=1+\phi \alpha _{c,t}\), is an outcome of the “religious” political-economy equilibrium. Consequently the effective impact of the restrictiveness of religious proscriptions on economic development depends on the relative weight of religious authorities in political decision-making, which is endogenous in the model.

In various times and places, such as Golden Age Islam or medieval Europe, religious authorities were also directly involved in economic activities. Although we do not explicitly model this possibility here, it follows from our setup that religious authorities can benefit from a greater economic surplus since it provides more revenue for expenditure on religious services.

We also assume that \(F^{\prime }(m)<C^{\prime }(m)\) for all \(m>0\); i.e., that the marginal cost of infrastructure maintenance is smaller than the marginal cost of building infrastructure.

In turn, the relative political power of the groups is endogenously determined in the model; see Sect. 3.2.

In the logic of our model, religious infrastructure represents all those policies which are the outcome of political economy factors and whose effects are not fully internalized by the political economy process (and over which the political economy process does not have full commitment). With respect to these policies, the institutional forces identified in our analysis are salient.

In accordance with our interpretation of the political economy process, the social welfare function \(W_t\) can be thought as the objective of a “fictitious policy-maker,” who makes decisions based on the political weight of each segment of society.

This is just for simplicity and concreteness: all that is needed is that the ruler has large enough power with respect to the other members of society.

\({\overline{\tau }}\) \(<1\) is associated with the fiscal capacity of the ruler (i.e., the maximum tax rate implementable in this economy).

The equilibrium is fully characterized in the Appendix in supplementary file. Since there is a complementarity between the provision of the religious good \(m_{t}\) and the investments of the clerics in religious infrastructure \(\alpha _{c,t}\), the uniqueness of the equilibrium is not guaranteed. Under mild conditions, however, the equilibrium is uniquely determined.

In the societal equilibrium, the ruler takes as given citizens’ efforts and does not internalize the negative effect of taxation on the tax base. Therefore he chooses the maximum possible tax rate \({\overline{\tau }}\).

We assume that institutional design is myopic, anticipating only socio-economic outcomes one generation ahead. This implies that the institutional structure does not internalize institutional “slippery slopes," whereby moving to a different structure of decision rights may in turn trigger subsequent institutional changes leading to undesirable outcomes from the point of view of the initial structure. See Bisin and Verdier (2017) for a discussion of how this issue can be accounted for in this kind of framework.

In this sense, our conception of institutional change follows in the spirit of Greif and Laitin (2004), Greif (2006), and Bisin and Verdier (2017) in that institutions change over time in response to the actions taken by the relevant players at a point in time given the incentives they face at that time. As in our conception of \(\lambda _t\), such “quasi-parameters” (to use the term coined in Greif and Laitin (2004)) are exogenous to all players in period t but change over time in response to their actions.

Note that if secular individuals suffer less than religious individuals from religious proscriptions, an increase in the clerics’ weight \(\lambda _{t}\) is more likely to happen as civil society as a whole is less affected by the economic cost of such religious proscriptions. Formally, the threshold \({\overline{q}}(\lambda _{t})\) becomes smaller when religious proscriptions are less satisfied by secular individuals than by religious individuals.

Given the quadratic specification of the utility function \(U_{i}(e_{i})\), and substituting the optimal labor efforts in the utility of the citizens, we find that \(\Delta V_{Re}(\lambda _{t})=\Delta V_{S}(\lambda _{t})=\frac{(\tau \theta \alpha _{c}(\lambda _{t}))^{2}}{2(1+\phi \alpha _{c}(\lambda _{t}))}\), which is increasing in \(\lambda _{t}\).

Random economic shocks or uncertainty regarding the parameters would help provide a closer map with historical narratives. For instance, the re-emergence of European commerce around 1000CE could be construed as one such shock, as could the Mongol invasions of the Middle East or the Black Death. We stick to a deterministic model, however, since allowing for such stochastic structure should not change the qualitative insights of the model, while the analytical complexity would increase by orders of magnitude.

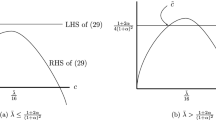

It can be shown that \(q^{*}(0)=0,\) and that \({\overline{q}}(0)>0\) with \({\overline{q}}^{\prime }(0)>0\). Under parametric conditions ensuring that \({\overline{q}}(1)<q^{*}(1),\) continuity of \({\overline{q}}(\lambda )\) and \(q^{*}(\lambda )\) implies that \({\overline{q}}(\lambda )\) necessarily cuts from below \(q^{*}(\lambda )\) characterizing an interior steady state point \(\left( q^{*},\lambda ^{*}\right)\) as shown in Figure 2. Such a point can be shown to be a saddle point steady state of the joint dynamics of culture and institutions, leading formally to the possibility of institutional divergence away from \(\left( q^{*},\lambda ^{*}\right)\). See Appendix in supplementary file A.6 for details.

\({\overline{q}}(\lambda )\) and \(q^{*}(\lambda )\) may intersect more than once at some interior point. This would provide other steady states whose dynamic stability will alternate between saddle points and stable points. The qualitative discussion of our analysis about institutional and cultural divergence between secular and a religious steady states are not affected by these possibilities.

Part of the reason for the dispute is the difficulty in interpreting the sources. The Abbasid Empire (750–1258), who followed the Umayyads, attempted to undermine the legitimacy and religious credentials of the Umayyads in order to justify their own rule. Historians have been forced to read between the lines to determine the degree to which the Umayyads (and early Abbasids) actually employed religious legitimacy. For more on this debate, see Donner (2010, 2020); El-Hibri (2002), and Anthony (2020).

For more on the role that tax revenue, particularly the jizya tax on non-Muslim subjects, played in conversion goals, see Saleh and Tirole (2021).

While we do not explicitly model discriminatory taxes, religious legitimacy works as such a tax in the model, given the presence of religious proscriptions. Formally including an explicit discriminatory tax would strengthen the results.

This notion of limited governance is akin to “inclusive political institutions” (Acemoglu & Robinson, 2012) or a broad-based ruling coalition (North et al., 2009). Limited governance is distinct from fiscal decentralization (Dincecco, 2009; Gennaioli & Rainer, 2007; Gennaioli & Voth, 2015). Fiscal decentralization is typically associated with lower tax revenue. Dincecco (2015) calls states that had both fiscal centralization and limited governance “effective states.” For more on the connection between fiscal capacity and executive constraint, see Mann (1986); North and Weingast (1989); Tilly (1990); Acemoglu et al. (2005b); Dincecco (2009); Besley and Persson (2009, 2010); Acemoglu and Robinson (2012, 2019); Bisin and Verdier (2017), and Johnson and Koyama (2017).

This is a simplification to reduce the dimensionality of the dynamics of institutions while expanding the qualitative features of the narrative of the interactions between ruler, clerics, and citizens analyzed in Sect. 3.

This setup captures the idea that there is an implicit bargaining process within the “secular ruling coalition” (ruler and secular elite) that is related to the institutional governance structure and which determines how the two parties share the rents extracted in society. This institutional structure implies that the equilibrium level of religious infrastructure only depends on the weight of the clerics relative to the secular ruling coalition, independent of the structure of power within the coalition.

For analytical convenience, we assume \(\epsilon (\alpha _{l,t})=\frac{\epsilon _{0}}{1-\alpha _{l,t}}\), so that \(\epsilon _{0}\in (0,1)\) is the enforcement level when the secular elites are not providing an effort (\(\alpha _{l,t}=0\)). For simplicity, we also assume that the maximum enforcement level that the secular elite can undertake \({\overline{\alpha }}_{l,t}\) is less than \(1-\epsilon _{0}\), so that \(\epsilon (\alpha _{l,t})\) always lies in the interval \([\epsilon _{0},1]\).

This consumption penalty is “burned out" and not recovered by tax collectors.

With this production specification, we highlight the distortions associated with the extensive margin of taxation, rather than the intensive margins of labor effort as in the base model. Introducing the intensive margin of production effort does not change the qualitative conclusions of this section, at the cost of increased analytical complexity.

When deciding on their optimal socialization effort, parents take into account that their children will draw in their adult life an idiosyncratic evasion capacity c, which matters for their decision to comply or not with taxation.

Because the equilibrium tax collection effort \(\alpha _{l}(\lambda ,\beta ,q)\) of the secular elite enters into the paternalistic motives, we note that \(\Delta V(\lambda _{t},\beta _{t},q_{t})\) is an increasing function of \(q_{t}\) (see the Appendix in supplementary file).

References

Acemoglu, D. (2005). Politics and Economics in Weak and Strong States. Journal of Monetary Economics, 52(7), 1199–1226.

Acemoglu, D., Egorov, G., & Sonin, K. (2015). Political economy in a changing world. Journal of Political Economy, 123(5), 1038–1086.

Acemoglu, D., Egorov, G., & Sonin, K. (2021). Institutional change and Institutional Persistence. In A. Bisin & G. Federico (Eds.), Handbook of Historical Economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier North Holland.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2012). Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty. New York: Crown.

Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty. New York: Penguin.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). Institutions as a fundamental cause of long-run growth. Handbook of Economic Growth, 1, 385–472.

Acemoglu, D., Johnson, S., & Robinson, J. A. (2005). The rise of Europe: Atlantic trade, institutional change, and economic growth. American Economic Review, 95(3), 546–579.

Angelucci, C., Meraglia, S., & Voigtländer, N. (2022). How Merchant towns shaped parliaments: From the Norman conquest of England to the great reform act. American Economic Review, 112(10), 3441–87.

Anthony, Sean W. (2020). Prophetic dominion, umayyad kingship: Varieties of mulk in the Early Islamic period. In The Umayyad World. Routledge pp. 39–64.

Ashraf, Q., & Galor, O. (2013). The “Out of Africa" hypothesis, human genetic diversity, and comparative economic development. American Economic Review, 103(1), 1–46.

Auriol, E., & Platteau, J.-P. (2017). Religious co-option in autocracy: A theory inspired by history. Journal of Development Economics, 127, 395–412.

Auriol, E., Platteau, J.-P., & Verdier, T. (2022). The Quran and the Sword. Journal of the European Economic Association 20(6).

Balla, E., & Johnson, N. D. (2009). Fiscal crisis and institutional change in the Ottoman empire and France. Journal of Economic History, 69(3), 809–845.

Barro, R. J., & McCleary, R. M. (2003). Religion and economic growth across countries. American Sociological Review, 68(5), 760–781.

Bénabou, R., Ticchi, D., & Vindigni, A. (2015). Religion and innovation. American Economic Review, 105(5), 346–51.

Bénabou, R., Ticchi, D., & Vindigni, A. (2020). Forbidden fruits: The political economy of science, religion and growth. Working Paper.

Bentzen, J, & Gokmen, G. (2022). The power of religion. In: CEPR Discussion Paper No. DP14706.

Berman, H. J. (1983). Law and revolution: The formation of the western legal tradition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Besley, T., & Persson, T. (2009). The origins of state capacity: Property rights, taxation, and politics. American Economic Review, 99(4), 1218–44.

Besley, T., & Persson, T. (2010). State capacity, conflict, and development. Econometrica, 78(1), 1–34.

Besley, T., & Persson, T. (2014). Why do developing countries tax so little? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 28(4), 99–120.

Bessard, F. (2020). Caliphs and merchants: Cities and economies of power in the near east (700–950). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (1998). On the cultural transmission of preferences for social status. Journal of Public Economics, 70(1), 75–97.

Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (2000). Beyond the melting pot: Cultural transmission, marriage, and the evolution of ethnic and religious traits. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 955–988.

Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (2001). The economics of cultural transmission and the dynamics of preferences. Journal of Economic Theory, 97(2), 298–319.

Bisin, A, & Verdier, T. (2011). The economics of cultural transmission and socialization. In: J. Benhabib, A. Bisin and M. Jackson (Eds.), Handbook of social economics, Vol. 1 Elsevier pp. 339–416.

Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (2017). On the joint evolution of culture and institutions. NBER Working Paper 23375.

Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (2021). Phase diagrams in historical economics: Culture and institutions. In A. Bisin & G. Federico (Eds.), Handbook of historical economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier North Holland.

Bisin, A., & Verdier, T. (2022) Advances in the economic theory of cultural transmission. Technical report. NBER Working Paper 30466.

Blaydes, L., & Chaney, E. (2013). The feudal revolution and Europe’s rise: Political divergence of the Christian West and the Muslim World before 1500 CE. American Political Science Review, 107(1), 16–34.

Blaydes, L., Grimmer, J., & McQueen, A. (2018). Mirrors for princes and sultans: Advice on the art of governance in the Medieval Christian and Islamic worlds. Journal of Politics, 80(4), 1150–1167.

Bockstette, V., Chanda, A., & Putterman, L. (2002). States and markets: The advantage of an early start. Journal of Economic Growth, 7, 347–369.

Bosker, M., Buringh, E., & Zanden, J. L. V. (2013). From Baghdad to London: Unraveling urban development in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, 800–1800. Review of Economics and Statistics, 95(4), 1418–1437.

Boyd, R., & Richerson, P. J. (1985). Culture and the evolutionary process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Cantoni, D., Dittmar, J., & Yuchtman, N. (2018). Religious competition and reallocation: The political economy of secularization in the protestant reformation. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 133(4), 2037–2096.

Cantoni, D., & Yuchtman, N. (2014). Medieval universities, legal institutions, and the commercial revolution. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 129(2), 823–887.

Cavalli-Sforza, L. L., & Feldman, M. W. (1981). Cultural transmission and evolution: A quantitative approach. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Chaney, E. (2013). Revolt on the Nile: Economic shocks, religion, and political power. Econometrica, 81(5), 2033–2053.

Chaney, E. (2016). Religion and the rise and fall of Islamic science. Working Paper.

Coşgel, M. M., & Miceli, T. J. (2005). Risk, transaction costs, and tax assignment: Government finance in the Ottoman Empire. Journal of Economic History, 65(3), 806–821.

Coşgel, M. M., Miceli, T. J., & Rubin, J. (2012). The political economy of mass printing: Legitimacy and Technological change in the Ottoman Empire. Journal of Comparative Economics, 40(3), 357–371.

Coşgel, M. M., Miceli, T. J., & Ahmed, R. (2009). Law, state power, and taxation in Islamic history. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 71(3), 704–717.

Coşgel, M., & Miceli, T. J. (2009). State and religion. Journal of Comparative Economics, 37(3), 402–416.

Coulson, N. J. (1969). Conflicts and tensions in Islamic jurisprudence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Crone, P., & Hinds, M. (1986). God’s Caliph: Religious authority in the first centuries of Islam. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Davids, K. (2013). Religion, technology, and the great and little divergences: China and Europe compared, c. 700–1800. Leiden: Brill.

de Lara, G., Yadira, A. G., & Jha, S. (2008). The administrative foundations of self-enforcing constitutions. American Economic Review, 98(2), 105–09.

Dincecco, M. (2009). Fiscal centralization, limited government, and public revenues in Europe, 1650–1913. Journal of Economic History, 69(1), 48–103.

Dincecco, M. (2015). The rise of effective states in Europe. The Journal of Economic History, 75(3), 901–918.

Donner, F. M. (2010). Umayyad efforts at legitimation: The Umayyads’ silent heritage. In: Umayyad Legacies. Brill pp. 185–211.

Donner, F. M. (2020). Narratives of Islamic origins: The beginnings of Islamic historical writing. Gerlach Press.

Duby, G. (1982). The three orders: Feudal society imagined. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

El-Hibri, T. (2002). The redemption of Umayyad memory by the Abbāsids. Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 61(4), 241–265.

Ensminger, J. (1997). Transaction costs and Islam: Explaining conversion in Africa. Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, 153(1), 4–29.

Feldman, S. M. (1997). Please don’t wish me a Merry Christmas: A critical history of the separation of church and state. New York: NYU Press.

Freidenreich, D. (2013). Food-related interaction among Christians, Muslims, and Jews in high and late medieval latin christendom. History Compass, 1(11), 957–966.

Freidenreich, D. (2015). Dietary laws. In: A Silverstein, G. G. Stroumsa and Moshe Blidstein (Ed.), The Oxford Handbook of the Habrahamic religions, Oxford University Press pp. 466–482.

Galor, O. (2022). The journey of humanity: The origins of wealth and inequality. Penguin.

Galor, O., & Moav, O. (2002). Natural selection and the origin of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117(4), 1133–1191.

Galor, O., & Özak, Ö. (2016). The agricultural origins of time preference. American Economic Review, 106(10), 3064–3103.

Gennaioli, N., & Voth, H.-J. (2015). State capacity and military conflict. Review of Economic Studies, 82(4), 1409–1448.

Gennaioli, N., & Rainer, I. (2007). The modern impact of precolonial centralization in Africa. Journal of Economic Growth, 12(3), 185–234.

Gill, A. (1998). Rendering Unto Caesar: The catholic church and the state in Latin America. University of Chicago Press.

Gilley, B. (2006). The meaning and measure of state legitimacy: Results for 72 countries. European Journal of Political Research, 45(3), 499–525.

Gilley, B. (2008). Legitimacy and institutional change: The case of China. Comparative Political Studies, 41(3), 259–284.

Greif, A. (2006). Institutions and the path to the modern economy: Lessons from medieval trade. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Greif, A. (2008). The impact of administrative power on political and economic developments: Toward a political economy of implementation. In: E. Helpman (Ed.), Institutions and economic performance, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press pp. 17–63.

Greif, A., & Laitin, D. D. (2004). A theory of endogenous institutional change. American Political Science Review, 98(4), 633–652.

Greif, A., & Rubin, J. (2023a). Endogenous political legitimacy: The Tudor roots of England’s constitutional governance. Working paper.

Greif, A., & Rubin, J. (2023b). Political legitimacy in historical political economy. In: J. Jenkins and J. Rubin (Ed.), Oxford handbook of historical political economy, New York: Oxford University Press p. forthcoming.

Greif, A., & Tadelis, S. (2010). A theory of moral persistence: Crypto-morality and political legitimacy. Journal of Comparative Economics, 38(3), 229–244.

Guo, B. (2003). Political legitimacy and China’s transition. Journal of Chinese Political Science, 8(1), 1–25.

Hallaq, W. B. (1984). Was the gate of Ijtihad closed? International Journal of Middle East Studies, 16(1), 3–41.

Hallaq, W. B. (2001). Authority, continuity and change in Islamic law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hallaq, W. B. (2005). The origins and evolution of Islamic law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hechter, M. (2009). Legitimacy in the modern world. American Behavioral Scientist, 53(3), 279–288.

Hollenbach, F. M., & Pierskalla, J. H. (2020). State-building and the origin of universities in Europe, 800-1800. Working Paper.

Hurd, I. (1999). Legitimacy and authority in international politics. International Organization, 53(2), 379–408.

Imber, C. (1997). Ebu’s-su‘ud: The Islamic legal tradition. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Iyigun, M., Rubin, J., & Seror, A. (2021). A theory of cultural revivals. European Economic Review, 135, 103734.

Johnson, N. D., & Koyama, M. (2017). States and economic growth: Capacity and constraints. Explorations in Economic History, 64, 1–20.

Karaman, K. K., & Pamuk, Ş. (2013). Different paths to the modern state in Europe: The interaction between warfare, economic structure, and political regime. American Political Science Review, 107(3), 603–626.

Karaman, K. (2009). Decentralized coercion and self-restraint in provincial taxation: The Ottoman Empire, 15th-16th centuries. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 71(3), 690–703.

Kuran, T. (2005). The absence of the corporation in Islamic law: Origins and persistence. American Journal of Comparative Law, 53(4), 785–834.

Kuran, T. (2011). The long divergence: How Islamic law held back the middle east. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kuran, T., & Rubin, J. (2018). The financial power of the powerless: Socio-economic status and interest rates under partial rule of law. Economic Journal, 128(609), 758–796.

Kuru, A. T. (2019). Islam, authoritarianism, and underdevelopment: A global and historical comparison. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lagunoff, R. (2009). Dynamic stability and reform of political institutions. Games and Economic Behavior, 67(2), 569–583.

Levi, M., & Sacks, A. (2009). Legitimating beliefs: Sources and indicators. Regulation & Governance, 3(4), 311–333.

Levi, M., Sacks, A., & Tyler, T. (2009). Conceptualizing legitimacy, measuring legitimating beliefs. American Behavioral Scientist, 53(3), 354–375.

Lewis, B. (1974). Islam: From the Prophet Muhammad to the capture of Constantinople. New York: Harper and Row.

Lewis, B. (2002). What went wrong?: The clash between Islam and modernity in the middle east. New York: Harper Collins.

Lipset, S. M. (1959). Some social requisites of democracy: Economic development and political legitimacy. American Political Science Review, 53(1), 69–105.

Ma, D., & Rubin, J. (2019). The paradox of power: Principal-agent problems and administrative capacity in Imperial China (and other absolutist regimes). Journal of Comparative Economics, 47, 277–294.

Mann, M. (1986). The sources of social power: A history of power from the beginning to A.D. 1760. Vol. 1 Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCleary, R. M., & Barro, R. J. (2019). The wealth of religions: The political economy of believing and belonging. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Michalopoulos, S., Naghavi, A., & Prarolo, G. (2016). Islam, inequality and pre-industrial comparative development. Journal of Development Economics, 120, 86–98.

Michalopoulos, S., Naghavi, A., & Prarolo, G. (2018). Trade and geography in the spread of Islam. Economic Journal, 128(616), 3210–3241.

Mokyr, J. (1990). The lever of riches: Technological creativity and economic progress. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mokyr, J. (2010). The enlightened economy: An economic history of Britain, 1700–1850. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Mokyr, J. (2016). A culture of growth: The origins of the modern economy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Noonan, J. T. (1957). The scholastic analysis of Usury. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Noonan, J. T. (2005). A church that can and cannot change: The development of catholic moral teaching. South Bend, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

North, D. C., & Weingast, B. R. (1989). Constitutions and commitment: The evolution of institutions governing public choice in seventeenth-century England. Journal of Economic History, 49(4), 803–832.

North, D. C., Wallis, J. J., & Weingast, B. R. (2009). Violence and social orders: A conceptual framework for interpreting recorded human history. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Özmucur, S., & Pamuk, Ş. (2002). Real wages and standards of living in the Ottoman empire, 1489–1914. Journal of Economic History, 62(2), 293–321.

Pamuk, Ş. (2004). The evolution of financial institutions in the Ottoman empire, 1600–1914. Financial History Review, 11(1), 7–32.

Pamuk, Ş. (2004). Institutional change and the longevity of the Ottoman empire, 1500–1800. Journal of Interdisciplinary History, 35(2), 225–247.

Paniagua, V., & Vogler, J. P. (2022). Economic elites and the constitutional design of sharing political power. Constitutional Political Economy, 33(1), 25–52.

Persson, T., & Tabellini, G. (2021). Culture, institutions, and policy. In A. Bisin & G. Federico (Eds.), Handbook of historical economics. Amsterdam: Elsevier North Holland.

Platteau, J.-P. (2017). Islam instrumentalized: Religion and politics in historical perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Putnam, R. D., Leonardi, R., & Nanetti, R. Y. (1994). Making democracy work: Civic traditions in modern Italy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Rubin, J. (2010). Bills of exchange, interest bans, and impersonal exchange in Islam and Christianity. Explorations in Economic History, 47(2), 213–227.

Rubin, J. (2011). Institutions, the rise of commerce and the persistence of laws: Interest restrictions in Islam and Christianity. Economic Journal, 121(557), 1310–1339.

Rubin, J. (2017). Rulers, religion, and riches: Why the west got rich and the middle east did not. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Rubin, U. (2003). Prophets and caliphs: The biblical foundations of the Umayyad authority. In: Method and theory in the study of Islamic origins. Brill pp. 73–99.

Saleh, M. (2018). On the road to heaven: Taxation, conversions, and the Coptic-Muslim socioeconomic gap in Medieval Egypt. Journal of Economic History, 78(2), 394–434.

Saleh, M., & Tirole, J. (2021). Taxing identity: Theory and evidence from early Islam. Econometrica, 89(4), 1881–1919.

Schacht, J. (1964). An introduction to Islamic law. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schulz, J. F. (2022). Kin networks and institutional development. Economic Journal, 132(647), 2578–2613.

Seror, A. (2018). A theory on the evolution of religious norms and economic prohibition. Journal of Development Economics, 134, 416–427.

Squicciarini, M. (2020). Devotion and development: Religiosity, education, and economic progress in 19th-century France. American Economic Review, 110(11), 3454–3491.

Stasavage, D. (2011). States of credit: Size, power, and the development of European polities. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stasavage, D. (2020). The Decline and rise of democracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Tierney, B. (1970). Western Europe in the middle ages, 300–1475. New York: Knopf.

Tierney, B. (1988). The crisis of Church and state, 1050–1300. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Tilly, C. (1990). Coercion, capital, and European states, AD 990–1990. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Tolan, J. (2019). Comparative remarks,a history of religious laws. In: R. Bottoni and S. Ferrari (Ed.), Routledge handbook of religious law, Routledge pp. 83–93.

Treisman, D. (2020). Democracy by mistake: How the errors of autocrats trigger transitions to freer government. American Political Science Review, 114(3), 792–810.

Tyler, T. R. (2006). Psychological perspectives on legitimacy and legitimation. Annual Review of Psychology, 57, 375–400.

van Zanden, J., Luiten, E. B., & Bosker, M. (2012). The rise and decline of European parliaments, 1188–1789. Economic History Review, 65(3), 835–861.

Weber, M. (1947). The theory of social and economic organization. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Weiss, B. (1978). Interpretation in lslamic law: The theory of Ijtihād. American Journal of Comparative Law, 26(2), 199–212.

White, L. (1972). Cultural Climates and Technological Advance in the Middle Ages. Viator, 2, 171–202.

White, L. T. (1978). Medieval religion and technology: Collected essays. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Wintrobe, R. (1998). The political economy of dictatorship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Thanks to Timur Kuran for excellent and detailed comments on an earlier draft of this paper. We also thank Oded Galor, four anonymous referees, Vladimir Asriyan, Marcello D’Amato, James Feigenbaum, Martin Fiszbein, Jordi Gali, Roger Lagunoff, Gilat Levy, Dilip Mookherjee, Andy Newman, Debraj Ray, Jaume Ventura and participants in seminars at Boston University, Brown University, George Mason University, Georgetown University, Iowa State University, LSE-NYU Conference in Political Science and Political Economy, Oxford University, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, UC Riverdale, Toulouse University, Vancouver School of Economics, CEPR Workshop on the Economics of Religion, ASSA, ASREC, Summer School for Quantitative History in Shanghai, DIAL, ThRed, and SIOE. Avner Seror acknowledges funding from the French government under the “France 2030” investment plan managed by the French National Research Agency (reference: ANR-17-EURE-0020) and from Excellence Initiative of Aix-Marseille University - A*MIDEX. All errors are our own.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bisin, A., Rubin, J., Seror, A. et al. Culture, institutions and the long divergence. J Econ Growth 29, 1–40 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-023-09227-7

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10887-023-09227-7