Abstract

This paper explores the link between infrastructures built by autocratic regimes and political values in the wake of the transition to democracy and in the long run. In Fascist Italy (1922–43), Mussolini founded 147 “New Towns” (Città di Fondazione). Exploring municipality-level data before and after their construction, I document (1) that the New Towns enhanced local electoral support for the Fascist Party and (2) that the effect persisted through democratization, enhancing local support for Italy’s neo-fascist party, which endured until recent times. Placebo estimates of New Towns planned but not built and spatial regression discontinuity design both support a causal interpretation of this pattern. Survey respondents near the New Towns currently exhibit preferences for a stronger leader in politics, for nationalism, and for the fascists as such. The effect is greater for individuals who lived under the Fascist Regime and is transmitted across generations inside the family. The findings suggest that authoritarian leaders may exploit public investment programs to induce a favorable view of their ideology, which persists across institutional transitions and over the long term.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Nationalism, racial resentment, xenophobia, and preferences for strong leaders are widespread. In the U.S., for instance, more than 30% of respondents to the 2010 World Value Surveys say that “it would be “good” or “very good” to have a “strong leader” who doesn’t have to “bother with parliament and elections” (Foa & Mounk, 2016). Such views are anything but new. They resemble the Fascist ideologies of the 1920s and 1930s, and so should recall memories of the disastrous experiences of those regimes, loss of freedom, and war. The persistent popularity of a rhetoric echoing such a dark past is puzzling.

The explanation may lie partly in the long-lasting impact of historical institutions on beliefs. But such an effect is ambiguous, ex ante. While institutions may complement beliefs (Alesina & Fuchs-Schundeln, 2007; Becker et al., 2016), they may also crowd out parental investment in transmitting those beliefs to their children (Lowes et al., 2017), so the effect of institutions on values is ambiguous. In this context, the empirical challenge in establishing the direction of causality compounds the difficulty of identifying the mechanisms by which historical institutions may affect beliefs.

This paper examines these issues by investigating the relationship between infrastructure built by the Italian Fascist regime and political beliefs.Footnote 1 Authoritarian leaders often exploit infrastructure to expand their popular support.Footnote 2 I explore the case of Mussolini’s New Towns (Città di Fondazione)—a major infrastructural program running from 1922 until the early 1940s—and investigate whether it led to a more favorable view of Fascism and its ideology, possibly influencing the formation of political beliefs that persisted in the face of democratization and over the long run. Differences in the exposure to the infrastructures provide the ideal variation for empirical identification of a novel mechanism whereby historical institutions may have an enduring influence on political beliefs, which may persist via cultural transmission, in turn, casting new light on the persistent popularity of extremist, anti-democratic ideologies.

In line with the hypothesis, I find (1) that the foundation of the New Towns enhanced local electoral support for the Fascist Party at the onset of the regime; (2) that this effect persisted through democratization, favoring the emergence and persistence of one of the largest neo-fascist parties in the West; and (3) that the Fascist New Towns explain differences in current political and cultural attitudes that can be traced back to the Fascist ideology, including preferences for a strong leader, nationalism, and racial resentment.

When the Fascist Party came to power, a substantial part of the country consisted in swampland. An extensive program of land reclamation was instrumental for Mussolini to show the economic and technological competence of the regime. As the Party advertised, draining the swamps was an achievement of the Fascist government that neither the Roman Empire nor the Papal State had been capable of. Reclamation entailed massive infrastructural investment that was unprecedented in the history of the country, including dewatering plants, canals, bridges, roads, and buildings. These infrastructures formed the New Towns.

The towns of Littoria, whose name was rendered into English as “Fascistville” (Snowden, 2008), and Mussolinia are two of the 147 New Towns built by the regime in Fascist Italy. The foundation of modern cities constructed on former swampland was a key motif of Fascist propaganda and resonated internationally (Ghirardo, 1989; Kargon & Molella, 2008). After the end of the dictatorship, despite legal restrictions and social stigma against fascist principles, the political landscape saw the emergence of the Italian Social Movement (Movimento Sociale Italiano, MSI), a political party advocating ideological positions directly rooted in the Fascist regime. This neo-fascist party, while a political pariah and never in government, enjoyed steady electoral support of around 5%. Its ideological roots and its limited influence on policy offer a unique opportunity to investigate the ideological legacy of Italian Fascism. In the cities founded by the regime, the fairly substantial electoral support for the MSI is associated with neo-fascist rallies, which are the norm rather than the exception.Footnote 3

The empirical analysis uses a rich dataset at the level of Italian municipalities and at the individual level. Novel data on the location of the Fascist New Towns augmented with information digitized from primary sources on the historical map of the largest catchment area of the New Towns, as well as on the historical presence of malarial swamps—a key determinant of their location. These data are combined with a rich set of socioeconomic data from several censuses and detailed geographic information.

Support for the Fascists is measured by three sets of data. First, I use voting data to measure the electoral support for the Fascists in the two elections that took place before the institution of the dictatorship, in 1921 (the year before the initiation of the New Towns project) and 1924. Second, I investigate the footprint of the New Towns on voting choices after the demise of the dictatorship, gauged by the electoral support for the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement (MSI) in the eleven elections from the party’s formation in 1948 to its dissolution in 1992. Third, I use contemporary individual surveys on political and cultural values from the Italian National Election Studies (ITANES), which ask about respondents’ preferences for a stronger leader, their attitudes towards immigrants, electoral choices of the respondents and their parents, as well as other measures of preferences for fascism, nationalism, and racial resentment.

In line with the hypothesis, I document that areas near the Fascist New Towns exhibited larger increase in the electoral support for the Fascist Party between the elections of 1921 and 1924. The estimated coefficient is large. A 1-standard-deviation increase in proximity to the New Towns is associated with an increase in the Fascist vote of 10% of the average share in 1924. Next I investigate the persistent effect of the intervention, finding that areas near the Fascist New Towns exhibited significantly more electoral support for the neo-fascist party several decades after the demise of Fascism itself. For example, in the elections of 1992 a 1-standard-deviation increase in proximity to the New Towns was associated with an increase in neo-fascist electoral support of 20% of the party’s average share of the vote.

The Fascists may have chosen the location of the New Towns on the basis of preexisting popular support. This would be a concern if they had targeted places already exhibiting strong support. However, the election data for 1921, the year before the initiation of the New Towns project, indicate that the relevant areas were less supportive of the Fascists, which suggests that the estimated effect is a lower bound of the parameter of interest. The New Towns were built in former swamplands, so their location may have had an independent effect on political views. The dates of foundation show that the support for the Fascist Party increased only in the municipalities near the New Towns constructed just before the 1924 elections, and not in those near the towns founded just afterward, which suggests that absent the new towns Fascist electoral support would not have increased in those areas. Furthermore, if characteristics explaining the locations chosen had influenced political preferences, then the areas where towns were planned but not built should also exhibit greater support for the Fascists. Reassuringly, however, this is not the case: those places did not show greater support for the Fascist or neo-fascist party, thus further mitigating identification concerns.

Results are robust to a large set of controls including measures of elevation, suitability for wheat and agriculture, prevalence of (or suitability for) malaria, distance to water, macro-region fixed effects, pre-policy population level and market access, distance to large cities, local political pre-conditions, and WWII-related events. Results are also robust to the exclusion of traditionally right-wing regions, corrections for spatial correlation, and a host of other checks.

Finally, I exploit the fact that a subset of the New Towns was built within a large catchment area (comprensorio di bonifica). I take advantage of the discrete nature of the border of the catchment area and find a discrete increase in support for the neo-fascist party precisely at the border cutoff: specifically, up to 4 percentage points more support in municipalities just inside than in those just outside the area. This is quite a sizable effect, given the party’s national average vote of 5%. The spatial Regression Discontinuity identification assumption requires that there be no other relevant factors exhibiting a discrete change at the border. Robustness tests and placebo checks support this assumption.

Different factors may explain the effect of the Fascist infrastructures on voting outcomes long after the demise of the dictatorship. Even though during the Fascist period migration was severely restricted, politically motivated migration would be an explanation if the settlers of the New Towns were already in favor of the fascists. Fascistville (Littoria) and 20 more New Towns were built in the Agro Pontino area, which was the emblem of the reclamation project and by far the place that received the greatest number of settlers. This area provides the ideal setting to investigate settlers’ preexisting political ideology.

A major difficulty is to measure extremist ideology in the past. I tackle this issue by developing a novel names-based measure of nationalistic (proto-fascist) views. The myths of the nation, war interventionism, and colonial expansion were key ideological principles of the Fascist rhetoric. Individuals with those values were more likely to develop positive attitudes towards Fascism. I explore the prevalence of patriotic, pro-war, and pro-colonization first names as an indicator of parental transmission of nationalistic views. I then use two novel databases of individuals located in the Agro Pontino in the 1930–40s. One covers the family heads’ names of all of the 3300 families who settled in the area over the Fascist period. Another covers 4000 police records, which provide the names of the suspected dissenters of the Regime (non-fascists) and its supporters (fascists).Footnote 4 I find that the prevalence of nationalistic names is twice as high for the fascists than for the non-fascists, in turn validating my names-based measure. I then find that the settlers (1) turn out to be less likely than the fascists to have nationalistic names; and (2) exhibited no difference in the prevalence of nationalistic names with respect to non-fascists. These findings indicate that the settlers were not already in favor of Fascism. Overall, these and other results do not point to migration as the main explanation.Footnote 5

An influential body of works examines the effect of institutions on political values.Footnote 6 Besley and Persson (2019a) show that autocratic institutions can influence the popular prevalence of political values that are then transmitted across generations. While persuasion has been shown to have important effects on beliefs also in democratic contexts (DellaVigna & Gentzkow, 2010; Guriev & Treisman, 2019) emphasize that authoritarian leaders take actions designed to show competence and enhance popular support. A view that finds empirical support in the context of the highway construction in Nazi Germany (Voigtlaender & Voth, 2014). I build upon this literature and advance the hypothesis that the Fascist New Towns influenced citizens’ opinion of the economic competence of the Fascists, fostering partisan identification and shifting beliefs towards Fascism (Ortoleva & Snowberg, 2015), which persisted across generations, despite democratization, via cultural transmission.Footnote 7

In line with this hypothesis, I find that the long-lasting legacy of the New Towns is greater in places where market access increased during Fascism (but not before), which citizens possibly linked to the new infrastructures. And is greater when the New Towns had larger infrastructural investments. In addition, estimates are larger in places where WWII Allies’ bombing attacks damaged infrastructures (but not other targets), possibly improving citizens’ appraisal of the Fascist works. I find limited evidence of explanations related to agricultural specialization, New Towns population size, the strength of local Fascist institutions, propaganda, or Fascist associations in the towns. Taken together, these findings point to the perceived economic improvements that —even if not caused by the New Towns or the Dictatorship—were associated with the fascist infrastructures, enhancing people’s attitudes towards Fascism.

I substantiate the effect on attitudes with survey data on political and cultural attitudes in recent times. Individuals near the New Towns built more than 70 years ago turn out to be more likely to be hostile to immigrants, to voice racial resentment, and to express preferences for fascists (but not other extremist parties or groups), for stronger leaders, and for nationalism —the central ideological pillars of the Fascist regime. The estimated link between New Towns and political attitudes is higher for individuals who actually lived under Fascism. And I find evidence that these political views were transmitted across generations from parents to children, in line with the vertical transmission cultural values (Bisin & Verdier, 2011).

This research mainly contributes to three strands of the literature. First, by exploring a novel mechanism whereby autocratic regimes may affect political attitudes, it may reconcile divergent views on the connection between institutions and political preferences and beliefs. For instance, Shiller et al. (1992) find no systematic differences in individual attitudes in surveys of three former communist and three capitalist countries. This concurs with the potentially slow-moving nature of cultural attitudes compared to institutions, as discussed by Roland (2004). Alesina and Fuchs-Schundeln (2007), by contrast, show that the exposure to communism in East Germany did influence redistributive preferences. The present paper indicates the role of heterogeneous exposure to regimes’ interventions in explaining these contrasting findings. Furthermore, while some works emphasize complementarity between institutions and cultural traits (Becker et al., 2016), other emphasize crowding-out effects (Lowes et al., 2017). Such contrasting findings point to the need to identify these mechanisms empirically, which I investigate by exploring a public investment program exploited by an autocracy to influence political views. Thus, the paper casts new light on the interaction between institutions and culture (Tabellini, 2008; Belloc et al., 2016; Bisin & Verdier, 2017; Buonanno et al., 2019).

Second, in exploring the link between infrastructures and political attitudes, this paper provides novel evidence on the long-term influence of historical events on attitudes.Footnote 8 While existing works have mainly studies traumatic episodes, including African slavery (Nunn & Wantchekon, 2011; Acharya et al., 2016), the Black Death (Voigtländer & Voth, 2012), natural disasters (Bentzen, 2019), and the WWII Nazi troops (Fouka & Voth, 2013; Fontana et al., 2016), the present work analyzes a non-traumatic historical episode,Footnote 9 which induced positive attitudes.

Third, this paper is related to the political economy literature studying the interlink between public funds allocation and electoral support. Recently, Finan and Mazzocco (2021) explore how politicians interest in getting elected, along with their interest in the welfare of people from their state, affect the allocation of public funds and welfare in the context of Brazil. Glaeser and Ponzetto (2018) show that voter attention can shift democratic governments provision of public funds away from the socially optimal level. The present paper differs from this stream of works as it focuses on the electoral consequences of infrastructures rather than their determinants, in line with (Cinnirella & Schueler, 2017; Drazen & Eslava, 2010; Levitt & Snyder Jr, 1997; Manacorda et al., 2011; Huet-Vaughn, 2019; Caprettini et al., 2021). And adds a focus on the autocratic context, thus related to Voigtlaender and Voth (2014), who show that railways boosted Nazis popular support. Yet, differently from Germany, in Italy the Neo-fascist party was admitted to the polls after the collapse of the dictatorship. I explore this unique setting to study the link between infrastructures and the electoral support for the Neo-fascist party after the end of the Regime, thus emphasizing the persistent influence of the intervention across a major institutional transition via persistence in political attitudes—a key innovation with respect to the aforementioned literature. That also links this work to the literature on the persistent effects of authoritarian interventions on political beliefs, which hitherto mainly focused on indoctrination and repression (Voigtländer & Voth, 2015; Xue & Koyama, 2016). Thus the paper provides an explanation for the persistent popularity of extremist ideologies, and complement works that take them as given (e.g. Cantoni et al., 2019).Footnote 10

2 Historical background

Seemingly of little significance at the time, an event that occurred in Milan on 23 March 1919 would shape the history of the world. Previously expelled from the Italian Socialist Party (PSI) for his nationalistic stance in favor of intervention in the Great War, a journalist named Benito Mussolini formed a new political movement called the Italian Fasci of Combat. The Fasci were composed of people from different social classes and political views, united by the principles of war interventionism and nationalism (Leoni, 1971; Lyttelton, 2004). The elections of 1921 saw the new party’s debut on the national political scene. Only one year later, Mussolini, with his followers, conducted a “march on Rome” to become prime minister. The consolidation of Mussolini’s power came with the 1924 elections. After another year dictatorship was officially instituted and all the other parties outlawed.

For centuries, the Roman Empire had sought unsuccessfully to drain the malarial swamplands. By implementing a major land reclamation, “where Caesars had fallen short the Duce prevailed” (Kargon & Molella, 2008, p. 50). Before the Fascist regime, the attempts to drain the swamps failed mainly because they dealt only with the problem of the excess of water in the swampland itself. By contrast, the Fascist reclamation project intervened also in the nearby territories (Ramadoro, 1930). To reduce the excess water they undertook hydraulic engineering both in the flat lands covered by swamps and also in the nearby mountainous areas, reforestation, and rearrangement of rivers and canals for drainage. On these canals they built bridges, and then roads and buildings. These major infrastructural investments formed the New Towns.

Mussolini founded them with the objective of exhibiting Italy’s power to the rest of the world and forging nationalistic sentiment and political support for the Fascist Party. The towns were populated with settlers recruited directly from areas with similar environmental and agricultural conditions—mainly the Veneto region (Pennacchi & Caracciolo, 2003; Protasi & Sonnino, 2003; Snowden, 2008; Treves, 1976). While the limited benefits of the sharecropper contract offered to the settlers (Treves, 1976, p. 76) and the inhospitable environment induced dissatisfaction and the desire of many to return homeFootnote 11 (Ipsen, 1996, p. 107) “the New Towns were of enormous propaganda significance for the government, whose ability to produce functioning towns from swamplands in a very short time, almost by magic, certainly enhanced the propaganda value of the reclamation” (Ghirardo, 1989, p. 26).

After the demise of the dictatorship, the Italian political scene saw the emergence of the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement. Founded in 1946 by veterans of Mussolini’s Italian Social Republic, the party, though politically marginal, was the fourth largest in Italy and “possibly the strongest neo-fascist Party in the advanced industrial countries” (Ferraresi, 1988). It was rooted in the ideology of the former regime: hierarchy, obedience to the leader, and nationalism.

The MSI’s electoral support was relatively stable throughout the second half of the 20th century, with an average of about 5% of the vote, but it never formed part of any government coalition. Its ideological proximity with the Fascist regime, together with its limited role in policy implementation, provides a unique opportunity to investigate the ideological legacy of Italian Fascism in postwar politics and develop novel evidence on the persistence effect of the New Towns on political attitudes.

3 The data

This section describes the data used for the empirical analysis. They cover more than 7000 municipalities over almost a century, combined with contemporary survey data for over 3000 respondents and geographic information. To a substantial degree the historical data have been digitized from primary sources. What follows is a brief description of the main variables and sources. For greater detail, see Online Appendix E.

For decades the historical literature dealt chiefly with the land reclamation and infrastructural investments in the Pontine Marshes southeast of Rome, while research into the New Towns built in the rest of the country was limited. However, Pennacchi and Caracciolo (2003) and Pennacchi (2008) have now presented an inventory of the New Towns, that builds on archival sources and previous works, including Protasi and Sonnino (2003), as well as Mariani (1976), Nuti and Martinelli (1981) and Fagiolo and Madonna (1994). The New Towns are defined as new urban settlements planned from their inception (Martinelli & Nuti, 1978; Pennacchi & Caracciolo, 2003). The inventory includes a total of 147 of them built over the study period, and another 15 were planned but not built because of the war (Protasi & Sonnino, 2003).Footnote 12

The data on infrastructure location also include the historical map of the largest catchment area of the New Towns (comprensorio di bonifica) from the official records of the Undersecretary of the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (Tassinari, 1939). Reassuringly, as shown in the following, the empirical evidence based on these alternative sources is in line with the hypothesis.

To investigate the enduring influence of the Fascist New Towns on political attitudes, I explore electoral outcomes and survey data. Electoral outcomes are the share of votes won by a party in the elections for the Chamber of Deputies. The parties considered are the Fascist Party, before and during the construction of the New Towns, and the neo-fascist party (MSI) for the period after the end of the dictatorship. The data are drawn from Corbetta and Piretti (2009).

The main analysis is based on outcomes for the period after the dictatorship. I employ voting records for more than 7000 municipalities. Electoral outcomes are measured as the share of the vote for the neo-fascist MSI in the 11 general elections from 1948 (the first time the neo-fascists were admitted to the polls) to 1992. After 1992, the scandals that affected the Italian political environment caused the dissolution of most political parties in their original form, including the MSI.

Figure 1, panel (a), depicts the electoral support for the neo-fascist party in 1992, the last elections in which it participated, and the location of the New Towns, which were built up to seven decades earlier under Fascism. As is evident from the map, greater support for the MSI is associated with proximity to the New Towns. This is particularly evident on the west coast of the peninsula, where several New Towns were built, but also on the east coast, in western Sardinia, and the North-East. To better visualize the relationship between proximity to the New Towns and the neo-fascist vote, Fig. 1, panel (b), depicts the average neo-fascist vote at different distances from the nearest New Town. Consistently with the hypothesis, greater distance is negatively associated with support for the MSI in 1992.

Mussolini’s New Towns and the Electoral Support for the Neo-fascist Party in 1992. Notes: Panel a shows a map of the share of votes for the neo-fascist party (MSI) in 1992 and the location of the Fascist New Towns. Panel b shows a histogram of the share of votes for the neo-fascist party (MSI) in 1992 for different distance intervals to the nearest New Town. A similar figure for the 1924 electoral support for the Fascist Party is depicted in Online Appendix Figure A8. A histogram with a larger set of distance intervals is provided in Online Appendix A, Figure A4

I complement long-run results with evidence on the short-term effects of the New Towns. I use voting records for the 1921 and 1924 elections, which is a more limited sample and covers more than 2000 municipalities. The Fascist Party took part in the 1921 elections as a part of larger political entities (electoral slates). These slates (lists) are indicated in the official electoral statisticsFootnote 13 and in Leoni (1971), as explained in detail in Online Appendix E. Among these slates, the right-wing coalition called National Blocs, included the Italian Nationalist Association, the former Prime Minister Giolitti, and the Italian Fasci of Combat led by Mussolini. I measure popular support for fascist views in 1921 as the total vote for this right-wing coalition.Footnote 14 As is shown below, the validity of this gauge is empirically supported by its strong positive correlation with the vote for the Fascist Party in 1924, when the Party took part independently, in its own name. In Sect. 6.1, I show that the electoral results of 1924 are highly correlated with those of the free elections of other years. This suggests that, while Fascist intimidation may have influenced the average vote on that year, heterogeneity in the 1924 voting share reflect differences in electoral preferences for (or in the absence of resistance to) the Party.

In the empirical analysis I control for a host of observable characteristics to allay concerns about potential confounding factors. I take into account geographic differences across municipalities including measures of elevation and distance to water. I calculate the municipality-level average suitability for agriculture (measured by the Caloric Suitability Index of Galor and Özak (2015)) and for producing wheat (from the Food and Agricultural Organization, Global Agro-Ecological Zones). The suitability data, which are originally in raster form, have been averaged within the boundary of each municipality. I take into account differences in the prevalence of (or suitability for) malaria, population and market access before the intervention, and distance to the closest major urban centers.Footnote 15

In addition to voting outcomes, I measure differences in political attitudes and cultural values using individual survey data from the Italian National Election Studies (ITANES) for 2001, 2004, and 2008. The surveys ask several questions that can be used to measure the similarity of individual political preferences to Fascist ideology: measures of nationalism, preference for a stronger leader, for the fascists, for racists, measures of feelings against migrants and others. The surveys also provide an extensive set of demographic characteristics, information on migration, socioeconomic status of the respondent and the respondent’s parents, and more.

4 Short-term effects

Mussolini became prime minister in 1922, so there is no reason to believe that the New Towns should have had a positive effect on support for the Fascist Party before that date. In Table 1, Column 1 shows the coefficient of a regression of the electoral support for the Fascist Party in 1921 (before the New Towns) and the log of the distance to the closest New Town. The estimated coefficient is positive. That is, the areas in the proximity of the New Towns displayed less support for the Fascist Party. Thus the Fascist government built the New Towns in areas where the support for the Party was weaker. Such a selection rule would, if anything, underestimate the link between the New Towns and Fascist support in later periods.Footnote 16

Column 2 shows that, in line with the hypothesis, the coefficient is negative and statistically significant for the relevant outcome, namely electoral support for the Fascist Party in 1924. The coefficient also indicates that the effect is substantial. A 1-standard-deviation increase in the log-distance is associated with lower support for the Party in 1924 equal to 24% of a standard deviation (6 percentage points).

For 83% of the New Towns, information on the year when construction was initiated is available. Constructions dates—described in detail in Online Appendix A, Figures A1 and A3—show that only a subset of the New Towns was built before 1924. So if the estimated relationship was due to the infrastructure, then only those built before the 1924 elections should be factors in the estimated coefficient. I investigate this hypothesis in column 3, which restricts the computation of the distance measure to the New Towns already under construction in 1924. As hypothesized, the coefficient is negative and highly significant.Footnote 17

As a falsification test, I employ as an explanatory variable the distance to the closest New Town that was initiated after 1924, distinguishing in column 4 between the distance to the New Towns already under construction in 1924 and the distance to those initiated afterwards. Again, only the distance to the relevant New Towns is statistically significant.Footnote 18 Finally, column 5 regresses electoral support in 1924 on the minimum distance to New Towns planned but not built. Reassuringly, in this case the coefficient is statistically indistinguishable from zero, suggesting that the estimated coefficient is not due to confounding factors.

Table 2 investigates the relationship between the distance to the New Towns that were already under construction and the share of votes for the Fascist Party in 1924, conditioning on the support in 1921 and other controls explained below. Column 1 shows the unconditional relationship between the two variables. The estimated coefficient is negative and statistically significant: a 1-standard-deviation increase in the distance to the closest New Town implies 28% of a standard deviation lower support for the Fascist Party in 1924. Column 2 includes as a control the electoral support for the Fascist Party in 1921. Thus, the coefficient is an estimate of the link between the distance to the closest New Town and the change in support for the Party.

Column 3 takes into account the variables that the historical literature sees as the major determinants of the location of the Fascist New Towns. In particular, given that they were built after land reclamation of malarial areas, the disease may have induced higher support for the extreme political positions of the Fascist Party. Column 3 tackles this issue by controlling for a dummy variable that taking value 1 if the municipality was affected by malaria in 1871.Footnote 19 Furthermore, I control for market access in 1921 and distance to the closest major urban center (see Online Appendix E for variables definition and sources).

Column 4 takes into account additional potentially confounding factors. Over the period of the Fascist dictatorship the Regime emphasized the role of agricultural production, thus potentially stimulating support from areas more suitable for agriculture. I take into account this potentially confounding factor by controlling for the Caloric Suitability Index (Galor & Özak, 2015)—a measure of suitability of the soil for agriculture. The Fascist Regime adopted a policy called Battle for Grain which, by favoring wheat producing areas (Carillo, 2021), may have induced a local shift in their political support. I take into account this potentially confounding factor by controlling for land suitability for wheat production. The estimated coefficient is robust to the inclusion of these controls, further highlighting the importance of the foundation of the Fascist New Towns in explaining differences in the support for the Fascist Party.

Column 5 controls for geographic conditions that may have been favorable for the presence of malarial swamps, in turn leading to the location of the New Towns. In particular, it includes distance to water, median elevation, standard deviation of elevation, and elevation range. The coefficient is not affected by these controls. Controlling for the size of the municipality, as measured by the logarithm of population in 1921, the coefficient remains negative and statistically significant (column 6). I correct inference by clustering standard errors at the provincial level.Footnote 20

Column 7 controls for the change in the total number of votes between 1921 and 1924, which may have been also induced by migration to the new towns. The estimated coefficient is unaffected by this control.Footnote 21 Additional evidence of the limited role of migration is provided in Sect. 7.1.4.

Here we have seen that distance to the New Town is related to electoral support for the Fascists only when the project was already in being, not before. Moreover, only the distance to the New Towns that were already under construction (not those not yet initiated) is relevant to explaining the Party’s electoral support in 1924.

To analyze the timing of the construction of the New Towns and the relationship with Fascist support more closely, Fig. 2 depicts a set of coefficients from two regressions. The squares are the estimated coefficients from a regression using as an outcome the share of votes for the Fascist Party in 1921 on a set of dummy variables taking value 1 if a New Town was initiated within 30 km in each year from 1922 until 1928.Footnote 22 The triangles are the coefficients from a similar regression but with the Fascist share of the vote in 1924 as outcome variable. Outcome variables are standardized and thus comparable. To get the appropriate control group, both regressions also control for a dummy indicating whether the construction of the New Town was begun in any year after 1928. The shaded area divides the estimated coefficients based on municipalities near the New Towns initiated before the 1924 elections (full symbols), from those near those built after that date (hollow symbols).

The Timing of the Treatment: Graphical Analysis. Notes: The figure shows estimated coefficients and 90% confidence intervals from two regressions. The squares are the coefficients from a regression of the share of votes for the Fascist Party in 1921 on dummy variables that take value 1 if the construction of a New Town was initiated within 30 km in a given year. The triangles are the coefficients from a regression of the share of votes for the Fascist Party in 1924 on the same dummy variables. The regressions also include a dummy taking value 1 if a New Town was built within 30 km in any year after 1928. The shaded area divides the estimated coefficients based on municipalities near the New Towns initiated before the 1924 elections (full symbols), from those near the New Towns built afterward (hollow symbols).

Three main elements emerge. First, full-colored squares for the years 1923 and 1924 tend to be below hollow squares in 1925 and 1926. Thus, not only were the New Towns built in places exhibiting low 1921 support for the Fascists; before the elections they were initiated in localities exhibiting even weaker support, suggesting that the timing of the infrastructure investment was chosen to boost electoral support in 1924. Second, the full-colored triangles for 1923 and 1924 are above the full-colored squares. This vertical difference is in line with the estimates of Table 2, which only explores the change in electoral support. Third, this vertical difference is positive and statistically significant only for municipalities in the proximity of New Towns built in 1923 and 1924, not after.Footnote 23 This finding strongly supports the hypothesis that the increase in electoral support would not have taken place in the absence of the infrastructures. Furthermore, Online Appendix Figure A3 Panel (b) shows that no construction was completed in 1923 and 1924, which suggests that the initiation of the towns was sufficient to induce a more favorable view of the dictatorship in the local populations. A more formal analysis of the hypothesis by estimating a regression model is performed in Online Appendix Section D.1.

5 Long-term effects

5.1 Neo-fascist vote

A number of works have shown that once political and cultural values are instilled they may be very persistent. Therefore, if the increased electoral support for the Fascist Party was associated with an effect on political attitudes, one may expect the effect to have persisted even after the end of the Fascist regime, leading to persistent differences in voting choices. Here I explore this hypothesis by studying whether the Fascist New Towns can explain differences in the support for Italy’s neo-fascist party more recently, when the regime was long gone. I then complement this analysis with Sect. 5.2, in which I explore the influence of the New Towns on measures of political attitudes.

Table 3, Panel A, presents the regression of the share of votes for the neo-fascist party in 1992 on the log-distance to the closest New Town.Footnote 24 Column 1 shows the unconditional relationship between these two variables. As hypothesized, the coefficient is negative, statistically significant, and large. Specifically, a 1-standard-deviation increase in proximity to the New Towns is associated with a 20% reduction in voting support for the neo-fascists in 1992.

Column 2 takes into account the presence of malaria,Footnote 25 market access in 1921, and distance to the closest urban center (see Online Appendix E for definition of the variables and sources). The coefficient remains negative and highly significant. Column 3 takes into account suitability for agriculture (the Caloric Suitability Index by Galor and Özak (2015)) and for wheat production, to capture the potentially confounding factor of the “Battle for Grain” (Carillo, 2021). The estimated coefficient is robust to the inclusion of these controls.

Column 4 controls for distance to water, median elevation, standard deviation of elevation, and elevation range. The coefficient is not affected by these additional controls. Column 5 takes into account population in 1921 and in 1991. The coefficient is still of the hypothesized sign and statistically significant. Finally, column 6 takes as explanatory variable the distance to New Towns that were planned but not built. Consistent with the hypothesis, distance to these sites is not negatively correlated with the support for the neo-fascist party. Actually the estimated coefficient is positive, which may be due by resentment or by the effect of potentially confounding factors opposite in sign to the coefficient of interest.

I investigate the limited role of unobservable characteristics associated with the location of the New Towns by employing variation across municipalities that are close to each other and thus similar. The results are given in Table 3, Panel B. To cast some light on the role of migration, column 1 excludes municipalities within 20 km of the closest New Town.Footnote 26 The coefficient remains high and statistically significant, thus suggesting that the results are not driven only by the New Towns (or by migration towards them) but also by the local populations in the surrounding areas. If the estimates were driven by areas far away from the New Towns, concerns on potentially unobserved confounding factors may arise. While this is partly taken into account with the use of log-distance, Column 2 further investigates this aspect excluding municipalities that are more than 80 km (about 50 miles) from the closest New Town. Remarkably, the coefficient barely changes, suggesting that the identifying variation comes from municipalities close to the New Towns rather than by the low support for Fascism in places that are far away.

Column 3 takes into account differences in unobservable characteristics across macro-regions by controlling for NUTS 1 regional fixed effects.Footnote 27 The coefficient remains statistically significant, suggesting that the results are not driven by regional heterogeneity.

To make sure that the use of a continuous measure of distance is not capturing some unobservable factors, column 4 employs as independent variable a dummy that takes value 1 if the closest New Town is within 30 km. Consistent with the hypothesis, the coefficient is positive and statistically significant, meaning that municipalities within 30 km of a New Town are characterized by greater support for the neo-fascist party, by 37% of a standard deviation. The coefficient is robust to the inclusion of macro region fixed effects, as demonstrated in column 5. Different cutoffs yield similar results, as shown in column 6 with a 20 km threshold (for different cutoffs and specifications across all the elections, see Online Appendix Figure A12). The results show that the New Towns can predict differences in the support for the neo-fascist party in 1992. In the following I explore the link between the towns and the evolution of the electoral support for the Fascist and neo-fascist parties.

The Evolution of the Support for Neo-Fascism and the New Towns. Notes: This figure shows the estimated coefficients and 90% confidence intervals, from a set of regressions of the electoral support for the neo-fascist party on the distance to the closest New Town. Each regression controls for baseline controls, including presence of malaria in 1870, distance to the closest provincial capital, and the standard measure of market access based on population in 1921. See Online Appendix E and main text for variables definition and sources. The coefficients of the figure are estimated in Online Appendix Table B20. Alternative specifications are shown in Online Appendix Figure A12

Figure 3 illustrates the estimated coefficients from regressing the electoral support for the neo-fascist party (after 1946) on the distance to the closest New Town. While election-specific fluctuations may be explained by supply-side shocks (Cantoni et al., 2019), in line with the hypothesis of this paper distance to the New Towns is associated with stronger support for the neo-fascist party from its onset (1948) to its dissolution (1992). The estimated effects are sizable. Across all elections, the standardized coefficients are around -.2%.

5.1.1 Spatial Regression Discontinuity Design

In addition to the effect of distance, the effect of the New Towns on attitudes towards Fascism may have been stronger in areas that actually received the infrastructures. This section explores this possibility in a spatial regression discontinuity (RD) design. In addition, by comparing areas very close to each other and thus similar in observable characteristics, this approach has the advantage of minimizing concerns on the direct effect of geography and other potential confounding factors on long-run voting outcomes.Footnote 28

A key aspect of the Fascist land reclamation project was that, rather than only targeting the swamps, it extended to their surrounding areas. Draining the swamps without resolving the cause of their formation was considered the main reason why the previous attempts failed. Conversely, by extending canals, roads, and other infrastructures to surrounding areas, the Fascist Regime could ensure that swamps would not reform (Ramadoro, 1930).

In south-east Italy, constructions took place beyond the swamps over a \(4000 km^2\) area called comprensorio di bonifica. The foundation of the New Towns in this “catchment” area entailed the construction of a very dense body of infrastructure facilities, including more than 360 km of roads, 20 km of canals crossed by a number of bridges and dewatering plants (Tassinari, 1939). While geographic conditions vary continuously across the catchment borders, the location of the catchment’s boundaries originated in a cost-benefit analysis, in turn, generating a plausibly exogenous spatial discontinuity in the allocation of infrastructures.

I employ a spatial RDD across the catchment area’s border for empirical identification of the effect of infrastructures on the support for the neo-fascist party. Figure 4 depicts a map of the study area and the study border, along with the location of the New Towns. The reclamation catchment area employed in the analysis was the largest of the comprensori di bonifica and thus proves a sufficient number of municipalities on both sides of the study border to allow the spatial RD analysis. While the swamps were located on coastal areas, the constructions took place also in the interior, thus minimizing concerns on preexisting hydro-geological differences between treated and control group. The figure also shows that the segment adopted in the spatial RD design, which is chosen as it does not overlap with administrative or geographical boundaries. Online Appendix Figure A13 shows a map of the catchment borders and elevation, indicating the absence of discontinuity in geography at the study border, which is formally investigated in the following.Footnote 29

The model employed to estimate the spatial RD coefficients is the local linear regression model, the forcing variable being the distance to the study border (Keele & Titiunik, 2015; Cattaneo et al., 2019). The linearity assumption requires performing the analysis within a very small distance to the border (defined bandwidth). The identification assumption is based on the characteristics other than the outcomes that vary continuously at the border.Footnote 30 I investigate this assumption by studying whether observable characteristics that induced land reclamation and the location of the catchment border (Ramadoro, 1930) vary smoothly at the border. Online Appendix Table B2 shows these placebo estimates of the local linear regression approach to the spatial RD design at the study border.

The estimates given in Online Appendix Table B2 are calculated within the data-driven optimal bandwidth, which is chosen in automatic fashion to avoid ad-hoc decisions (Calonico et al., 2014). The first column reports the outcome variables, the second column the estimated coefficient with the local linear regression model, and the third column the conventional confidence intervals. The fourth and fifth columns report the conventional and bias-robust P-values.

The coefficients suggest that socioeconomic conditions, as proxied by population in 1921, vary smoothly at the border. This is indicated by the fact that the P-values are all above the conventional levels of significance, especially those based on bias-robust estimates, which display values that are far from the conventional levels of statistical significance. Importantly, also population in 1936—after the construction of the towns in the area—vary smoothly at the border. Thus, indicating that migration-driven population growth was not significant at the discontinuity, and thus is unlikely to explain the findings. Additional evidence on the role of migration is discussed in Sect. 7.1.4.

As shown in the table, also suitability for wheat and suitability for agriculture do not change discretely at the border. In other words, cross-border geographical differences that may have implied high returns for the regime from investing in those places are not statistically significant. Elevation and distance to water are important determinants of the presence of swamps. Reassuringly, the mean and the standard deviation of elevation, as well as of distance to waterways, vary smoothly at the border.

The presence of malarial swamps was one of the key elements of the land reclamation infrastructure. In the last row of Online Appendix Table B2, I show the absence of a discontinuity in malaria suitability. This is an important result, because the presence of malarial swamps was an important determinant of the towns’ location but not of the location of the study border, thus strongly supporting the spatial RD identification assumption.Footnote 31 While these characteristics may vary significantly between treated and untreated areas, what is important in this setting is that they vary smoothly at the border. Overall, these results provide strong evidence in support of the identification assumption.

Having shown evidence in support of the identification strategy, Table 4 investigates the presence of a discontinuous increase in the vote share for the neo-fascist party across the study border. Panel A gives the estimates from the linear local regression analysis. For completeness, Panel B gives the estimates based on a second-order local polynomial.

The estimate for the 1992 elections in panel A indicates that municipalities just inside the catchment gave 4 percentage points more of the vote to the neo-fascist party than those just outside. The estimated coefficient is statistically significant at least at the 5% level both with the conventional and with the bias-robust p-values. Furthermore, it is large, equal to the party’s average percentage in the elections that year (descriptive statistics are reported in Online Appendix Table E33). Note that the estimate is within a 17-km bandwidth: that is, municipalities inside the catchment area within 8.5 km of the study border are compared to those up to 8.5 km outside the area. The small distance from the cutoff within which the municipalities are located, along with the lack of discrete changes in observable characteristics (Online Appendix Table B2), strongly supports the causal interpretation that the coefficients reflect the impact of the fascist infrastructures on support for the neo-fascist party.

The estimated coefficients for other elections too are positive and highly significant.Footnote 32 Panel B depicts the estimated coefficients with a quadratic polynomial. Apart from 1958, the estimates are very similar to the foregoing, or even slightly larger. Having non-linear specifications allows a larger sample (i.e. a broader bandwidth), which typically improves efficiency, at the cost of including observations that are further away and thus less comparable. For this reason, this is not my preferred specification, but in any case it is reassuring to see that the estimates are robust to this alternative specification.

Figure 5 displays several RD plots to visually investigate the presence of a discontinuity at the study border. For ease of visualization, each panel plots bins of data with average vote shares for the neo-fascist party against distance to the study border in kilometers, as well as a linear fit of the underlying data (for a non-linear fit, see Online Appendix Figure A17). Observations on the right-hand side of the border represent municipalities inside the catchment area. The panels show that there is a significant increase in electoral support for the neo-fascist party exactly at the cutoff.

The New Towns and the Neo-fascist Party: Regression Discontinuity Plots. Notes: The figures show the discontinuity in electoral support for the neo-fascist party at the border of the New Towns catchment area. The x-axis depicts distance to the cutoff in kilometers (positive within the area and negative outside it). Diagrams are qualitatively similar when a quadratic fit is used, as shown in Online Appendix Figure A17. For ease of visualization and consistency with the empirical analysis, plots are drawn within a small distance (40 km) to the cutoff

Online Appendix Figure A16 shows the spatial RD coefficients for all the elections ordered by year. The coefficient is positive and statistically significant for most of the elections. The years when it is not statistically distinguishable from zero may be explained by election-specific conditions. For instance, in the aftermath of the war very strong social stigma attached to any expression of fascist ideology, which may explain why the coefficient for 1948 elections is statistically indistinguishable from zero. In line with this interpretation, the neo-fascist vote in 1948 was just 2%, compared with almost 6% in 1953. Overall, these results indicate that being directly exposed to the program was an important element to boost Fascists electoral support, informing on how voters assess policymakers (Drago et al., 2020), and explaining voting choices over the long term.

5.2 Political attitudes

The investment undertaken in building the New Towns may have shaped political attitudes toward a more favorable view of the Fascist government and its political creed, ultimately influencing voting choices even after the demise of the dictatorship. While the estimated effects on voting behavior are in line with this hypothesis, four kinds of evidence would constitute strong support for an effect also on beliefs. First, neo-fascist voting preferences linked to the infrastructures could persist via a mechanism of cultural transmission. Second, individuals near the Fascist New Towns should display preferences in favor of the fascists as such. Third, they should exhibit political opinions that are close to Fascist principles. Fourth, the results should not be explained by individual migration patterns. In the following, I explore these hypotheses with rich individual-level survey data.

5.2.1 Neo-fascist voting preferences

The survey ITANES 2001 includes questions on whether the respondent has ever voted for the neo-fascist party, which I employ to cross-validate the results across municipalities.Footnote 33 Importantly, the survey also reports the voting behavior of the respondent’s parents, which I use to consider the inter-generational transmission of voting choice. The results are illustrated in Table 5.

Column 1 displays the estimates from regressing a binary outcome variable that takes value 1 if the respondent has ever voted for the neo-fascist party on the distance of the municipality from the closest Fascist New Town. Column 2 also controls for the baseline municipality-level factors: the presence of malaria in 1870, distance to the closest provincial capital, and the standard measure of market access based on population in 1921, i.e. before the construction of the New Towns.

Column 3 controls for a dummy that takes value 1 if the individual is in the same region as the father was when he was 14. This is an important source of variation given that, in the Italian context, migration took place predominantly across regions both during and after the regime (Treves, 1976). If the estimated coefficient were entirely driven by migration towards (or from areas near) the New Towns, then the introduction of this control should annihilate the estimates. In contrast, the comparison between column 2 and column 3 shows that, if anything, the estimated coefficient increases in magnitude (in absolute value), minimizing the possibility of migration as a main mechanism.

Average individual characteristics may differ in areas in the proximity of the New Towns and have an independent effect on the propensity of an individual to support the neo-fascist ideology. To take these potentially confounding factors into account, column 4 introduces a set of individual controls: age, years of education, gender, an indicator for married or not, number of children, an indicator variable for employed, and a set of indicator variables for salaried, self- or atypical employment. The introduction of these individual controls further improves the estimated coefficient, suggesting that individual characteristics, if anything, may bias the coefficient towards zero.

The sector in which the respondent is employed may affect the propensity to support the neo-fascist party independently of the presence of the New Towns. Similarly, the sector of the parents’ employment may determine cultural aspects that may influence the political propensities of the respondent. Column 5 controls for a set of indicator variables: sector in which the respondent is employed (agriculture, manufacturing, services, public administration), the sector in which the head of the household is employed, and the sector in which the father was employed when respondent was 14 y old (only available in the waves of 2001 and 2004). These additional controls further strengthen the estimated link between the Fascist New Towns and the propensity of the respondent to vote for the neo-fascist party.

Column 6 restricts the sample to individuals who are in the same region in which their father was at the age of 14. Reassuringly, the estimated coefficient holds despite the reduction in the number of observations. This further suggests that the effect of the infrastructures goes beyond the potential effect of migration.

5.2.2 Preferences for the fascists

I now explore differences in preferences for the fascists via the survey question: “There are groups of people whose opinions many people do not like. For each of these groups, tell me if you think they should be allowed or forbidden to publicly manifest. What do you think, for example, regarding the fascists?” This same question is asked for other groups: communists, racists, Muslims, homosexuals, and others.Footnote 34 The answer to the question embeds preferences for fascism together with preferences for giving the right to expression and demonstration. In fact, as shown in Online Appendix Table E35, despite the significant differences in political views between some of these groups, the answers to the question across groups are positively and significantly correlated. However, there are significant differences in the magnitudes of the correlations, suggesting that these data also contain information on individual preferences towards each of the groups.

Ideally, in order to isolate preference for the fascists, one should account for individual preferences in favor of freedom of expression in general. I tackle this issue by employing as an outcome the answer to the question on whether the fascists should have the right to expression, controlling for the answers to the same question for each of the other groups. Given that some are characterized by political attitudes related (positively or negatively) to fascism, controlling for all other answers is particularly conservative. Furthermore, given that the respondents are comparing extremist groups, they may be less likely to under-report, potentially underestimating preferences for the fascists. Table 6 illustrates the results that include the full set of control variables (see Online Appendix Table B14 for the results without these controls).Footnote 35

Column 1 uses as outcome whether the fascists should have freedom of expression, controlling for the answer to the same questions for each of the other groups. As hypothesized, the coefficient is negative, suggesting that respondents in the proximity of the New Towns are more likely to support fascists than any of the other groups.

Columns 2–8 employ as outcomes the answer to the same question for each of the other groups, controlling for the answers for all the remaining ones (including fascists). None of the coefficients from columns 2 to 7 is statistically significant. The coefficient in column 8 is positive and significant: here the outcome variable is the answer to the question whether people who want the secession of the North from the rest of Italy should be allowed free expression. Thus, low values indicate stronger preferences for national unity. The positive and statistically significant coefficient shows that in proximity to the New Towns respondents are less likely to support the secession of the North from the rest of Italy, showing greater support for national unity—a central element of the fascist ideology.Footnote 36 The table supports the hypothesis that the New Towns influenced preferences for fascists.

In the last period of the dictatorship, the Fascist regime also embraced and espoused racism and anti-Semitism. These views may still be present in the proximity of the New Towns. However, column 5 in Table 6 shows that, controlling for the support for the neo-fascist group, the respondents close to the New Towns do not seem to favor racists. Nevertheless, if the New Towns positively affected racist views through preferences for neo-fascists, then the removal of the control variable that captures such preferences should make the coefficient negative and significant. Remarkably, this is indeed the case (Online Appendix Table B16).

5.2.3 Persistence of fascist values

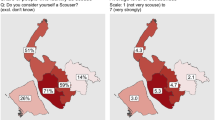

I explore differences in political opinions and vicinity to fascist views. For instance, “a central ideological tenet of Fascism was the cult of the omniscient and omnipotent leader” (Snowden, 2008, p. 143). Therefore, in areas more exposed to the Fascist New Towns, individuals may still display preferences for a strong leader in politics. By exploring the ITANES surveys conducted in 2001 and 2008, Online Appendix Table B4 investigates this hypothesis (see Online Appendix Table B15 for specifications without control variables). Column 1 takes as outcome the answer to the question on whether the country needs a strong leader (higher values of the outcome indicate stronger agreement). The coefficient is negative and significant, suggesting that respondents farther away from the New Towns are less likely to prefer stronger leaders.Footnote 37

The regime promoted the ideological principles of nationalism and also racism. Columns 2 and 3 employ as outcomes the answers to the questions whether immigrants are a threat to national culture/identity and employment, respectively. Higher values of the outcome indicate stronger agreement. In line with the hypothesis, both columns display negative and significant coefficients. Taken together, they indicate that proximity to the Fascist New Towns is associated with less tolerance for migrants and thus greater nationalistic sentiment.Footnote 38 While information on migration patterns is not available in the data employed in B4, these findings provide further evidence of the channel through which the fascist infrastructures persistently affected political and cultural values.

6 Robustness

The long-lasting shadow of the New Towns is estimated with, and robust to, a number of empirical strategies and estimation techniques (including spatial RDD) and a variety of databases from different sources. Besides the additional controls and interaction terms discussed in the following, Table 3 Panel B shows robustness to the use of local variation, including macro region fixed effects and sample cuts. To demonstrate that the results are not driven by specific regions, Online Appendix Table B22 shows robustness to the exclusion of each of the regions more exposed to the land reclamation project (Lazio, Apulia, and Sardinia). Restricting the sample within South-Island and Center-North regions, Online Appendix Table B22 shows that the estimates are larger within the South, possibly due to weaker preexisting political identity. The results also show robustness to alternative controls for malaria exposure (Online Appendix Table B10), to taking into account spatial correlation of the error term (Online Appendix Table B13), and show limited role of voting turnout (see Online Appendix Figure A10). Online Appendix Table B24 shows robustness of the results presented in Table 6 to the exclusion of (1) municipalities that are in the northern part of the Country, (2) municipalities that are far away from the New Towns, and (3) to the inclusion of macro-regions fixed effects. Section 6.1 provides evidence in favor of the hypothesis that the 1924 can be used as a measure of local support for the fascists, in line with other works (Acemoglu et al., 2022).

6.1 Intimidation and the 1924 electoral outcome

Violence and intimidation, which were often employed by the fascist squads, may have affected the electoral outcomes in the 1924 elections. In case of perfect intimidation, the support for the Fascist Party in those elections would have been 100% in all municipalities. Yet, there is significant variation in the electoral support for the Party in 1924. For example, about 10% of the municipalities exhibited less than 20% of the votes for the Party. Suggesting that intimidation was not perfect and that resistance to the regime was highly heterogeneous.

However, if intimidation was mainly used in the New Towns in boosting electoral support, then using 1924 electoral outcomes as a dependent variable may rise concerns on intimidation as an omitted factor. If instead intimidation was used far from the towns, then the estimated coefficient would be a lower bound of the true parameter of interest. Finally, intimidation may have been so pervasive and increase the average support for the country as a whole, in turn setting aside the role of intimidation as an omitted variable in the context of this study.

The latter hypothesis would be corroborated if the 1924 fascist votes are correlated with the support for the Neo-fascist party in the post-war period, when no intimidation took place. In contrast, if intimidation were the only driver of the electoral support in 1924, then there should be limited to no correlation between the fascist and Neo-fascist votes.

Persistence in the Support for Fascism. Notes: The figures show the striking correlation between the support for Neo-Fascism and for Fascism. The left panel shows binned scatter plots (30 equally-sized bins) of the share of votes for the neo-fascist party in 1953 and for the Fascist Party in 1924. The right panel shows the same graph excluding municipalities that exhibited no votes for the Fascist Party in 1924 and thus were presumably unaffected by the Fascist intimidation

In the first elections in which the neo-fascist party was allowed to participate (1948), social pressure against the ideology of the Fascist Regime discouraged people from voting for the neo-fascist party.Footnote 39 Thus, I look at the relationship between the electoral support for the Fascist Party in 1924 and for the Neo-fascist party in 1953, when there was no intimidation and limited social stigma associated to the Neo-fascist vote. Figure 6 shows a binned scatter plot of the electoral support for the Fascist Party in 1924 against the support for the neo-fascist party in 1953. The striking positive association displayed in the figure supports the hypothesis that intimidation was mainly enhancing the average support for the Fascist Party in the country as a whole. Or at least that, even though intimidation was present, differences in the 1924 fascist votes across municipalities captures meaningful variation in the differences in the resistance to the Fascist Regime.

7 Mechanisms

The New Towns built by the Fascist government can explain differences in voting patterns well beyond the end of the dictatorship, right up to quite recent times. The question is what mechanisms produced this persistent link. While various and possibly complementary channels may be at work, which may be investigated with various data and identification strategies, it will be of interest to cast light on some of these aspects empirically.

7.1 The nature of the treatment

7.1.1 New communities and the size of the new towns

By creating new communities the Fascists may have left a long-lasting cultural footprint in those places. This mechanism, which is in line with the hypothesis that public resources can be exploited by autocratic regimes to influence political support, may explain the estimated effect of distance if municipalities near the New Towns were exposed to the diffusion of political and cultural values from those communities. If this is the case, then larger communities in the New Towns may have led to larger electoral support for the neo-fascist Party. But large population in the New Towns may also be correlated with the size of the infrastructure investments, which may have independently induced a more favorable view of the Fascists in the neighboring communities. Table 7 investigates these mechanisms.

I employ population in the closest New Town to measure the size of the community in the New Town. Due to limited data, size of investment is proxied by the number of years it took to build the closest New Town. I find that the estimated effect of distance to the New Town is greater in places where construction took longer, which points to the effect of the infrastructure investment as a functioning mechanism. The interaction with population of the closest New Town (measured in 1936 or 1951) is insignificant, possibly because under Fascism any manifestation of dissent was severely punished and after the end of the dictatorship canvassing or explicitly supporting fascist ideology was illegal, which may have induced those values to diffuse through other channels rather than spatially.

7.1.2 New markets, local institutions, and agricultural specialization

Over the Fascist period, citizens in the proximity of the New Towns that also experienced a rise in living standards—even if not induced by Fascism—may have been more likely to be impressed by the economic competence of the regime. I explore this interaction of exposure to the New Towns with the perceived rise in living standard by interacting distance to the towns with the change in market access over the relevant period.Footnote 40 In line with the hypothesis, in column 1 of Table 8, I show that the effect of proximity to the New Towns on the support for the neo-fascist party is stronger where the increase in market access is greater. And in Online Appendix Section C.1, I show that this interaction term is statistically insignificant in all periods before the Fascist regime.

The strength of local Fascist institutions in the New Towns may explain the finding by virtue of a supply-side effect. For instance, Fascist leaders may have captured local power, influencing voting patterns even after the end of the dictatorship.Footnote 41 This mechanism may lead the effect of proximity to the New Towns to be larger in the new provinces created outright in 1927, given that local government there was created and administrators directly appointed by the Fascist regime (Sergi, 2011). I investigate this issue in column 2 of Table 8, finding that the interaction between distance to the New Towns and the Fascist provinces is not statistically different from zero, which suggests that the findings depend mainly on the hypothesized demand-side mechanism. The effect of the New Towns may differ based on specialization in agriculture. To capture exogenous characteristics that may explain differential specialization patterns, columns 3 and 4 explore interactions with suitability for wheat production and for agriculture, respectively. The statistical insignificance of the interactions terms indicates that the results are not explained by channels of agricultural specialization or by wheat specialization and the “battle for grain” campaign (Carillo, 2021).

7.1.3 Perceptions and propaganda: allied bombs and the radio

Citizens’ perception that the Fascists improved their well-being may explain the long-lasting political legacy of the New Towns. Bombing attacks occurring during WWII threatened the perceived benefits of the newly constructed Fascist infrastructures, possibly strengthening people’s appraisal of Fascists’ infrastructural project.Footnote 42 To cast light on this mechanism, I explore data provided by Gagliarducci et al. (2020) on municipality-level number of days of bombing attacks carried out by the Allied Forces in Italy during WWII from the Theater History of Operations Reports. I interact the intensity of bombings with the distance to the towns. The results are illustrated in Table 9.

Column 1 of Table 9 shows no significant interaction with the number of days the municipality was exposed to bombing attacks. Columns 2 and 3 distinguish between bombing attacks with non-infrastructural targets and those with infrastructural targets, respectively. Interestingly, only attacks targeting infrastructures interact with distance to the towns. This result is in line with the hypothesis that the perceived value of the Fascist infrastructures is a plausible explanation. Column 4 introduces both infrastructural and non-infrastructural bombings. Again, only the infrastructure-related bombings exhibit a significant interaction term. This significant interaction could be driven by bombings targeting the Fascist infrastructures. Column 5 excludes municipalities that were exposed to Allied Forces’ bombings and were located within 10 km from the New Towns. The results are unchanged. These findings suggest that the threat of non-fascist infrastructural damage enhanced the perceived value of the Fascist works and the long-lasting shadow of the New Towns.

The effect of the New Towns may also have been stronger in places exposed to the propaganda of the regime. I explore this possibility by using data by Gagliarducci et al. (2020) on municipality-level radio signal strength of the the official radio of the Fascist Regime (EIAR, Ente Italiano Audizioni Radiofoniche) which had great propaganda content (Cannistraro, 1975). Results using these data sources are displayed in column 6, which show no interaction with the fascist radio signal strength. While this finding may be due to the limited diffusion of the radio in Italy at that time, it may also indicate that in the context of the Fascist New Towns propaganda did not have long-lasting effects. Other results, available upon request, show absence of significant interactions with the other radio signals (e.g. the BBC) and with Nazi-fascist violence during WWII.

7.1.4 Migration and the new towns settlers

The Fascist regime ended Italian emigration (D’Amico & Patti, 2018) and imposed severe restrictions on internal migration (Bacci, 2015; Treves, 1980). However, politically motivated migration would be an explanation of the findings if the settlers of the New Towns were already in favor of the fascists. I investigate this aspect by gathering a novel database covering all the heads of the settlers families (more than 3300) of the Agro Pontino. The area included Fascistville (Littoria) and 20 more New Towns. It was the emblem of the reclamation project and by far the place that received the greatest number of settlers. Thus, it provides the ideal setting to study settlers’ ideology.

Investigating preexisting differences in ideologies poses two main challenges. The first is to measure political ideology in the past. I tackle this challenge by developing a novel names-based measure of preexisting pro-fascist views. The myths of the nation, war interventionism, and colonial expansion were key pillars of the Fascist ideology. To measure these sentiments, I explore a novel catalog of ideological first names developed by Pivato (1999), who uses a comprehensive database of Italian first names in the center-north of Italy and provides detailed explanations and evidence of the link between each name and the historical and political events to which they are linked.Footnote 43 He provides a catalog of names exhibiting patriotic sentiment (e.g. Italo, Patria), pro-war sentiment (e.g. Guerrino, Cecchino), and pro-colonial expansion (e.g. Eritreo, Libia). First names in these categories indicate political views in line with the main ideological elements of Italian Fascism.

The second challenge is to compare the settlers to individuals whose ideology is known and investigate possible differences. The ideal comparison groups would be one composed by individuals known to be fascists, and another by individuals known to be non-fascists. I tackle this challenge by gathering novel data covering more than 4000 individuals recorded by the Fascistville police (questura) for political reasons. During the dictatorship, police records cover individuals apprehended or surveilled for dissenting from the Regime. I code these individuals as non-fascists. After the dictatorship, police records cover individuals supporting the fallen Fascist Regime (which was outlawed). I code these individuals as fascists. I minimize risks of false positives using information on the “felony”, when available.Footnote 44 Importantly, even though police records are not a perfect assessment of the true political ideology, for the case at hand it suffices to isolate groups that are more (less) likely to be fascist.