Abstract

We construct the first consistent series on the long-term distribution of income in Poland by combining tax, household survey and national accounts data. We document a U-shaped evolution of inequalities from the end of the nineteenth century until today: (1) inequality was high before WWII; (2) abruptly fell after the introduction of communism in 1947 and stagnated at low levels during the whole communist period; (3) experienced a sharp rise with the return to capitalism in 1989. We find that official survey-based measures strongly under-estimate the rise in inequality since 1989. Our results highlight the prominent role of capital income in driving the U-shaped evolution of top income shares. The unique inequality history of Poland speaks to the central role of institutions and policies in shaping inequality in the long run.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Our understanding of the evolution of inequality and its determinants depends on the available empirical evidence. As we have obtained new evidence, charting inequality further back in time, the old paradigms have been challenged and new ones developed (Atkinson & Piketty, 2007, 2010; Kuznets, 1953; Piketty, 2001, 2014). Although numerous countries have been extensively studied, Poland has been missing from the picture. The episodes of state formation, war, socialism, transition into capitalism, and integration into the EU make Poland a particularly compelling case for studying the determinants and effects of income inequalities. More recently, Poland’s profound transformation from communism to a market economy happened in less than one generation, and the accompanying economic growth has been the fastest in Europe (Piątkowski, 2018), but little is known about which income groups have benefited from it. How do inequalities evolve in such fast-changing societies and what is the relative role of technological change versus transition policies and emerging institutions? The Polish economy has been also deeply transformed by the new wave of globalization. This is the only major European country which has recently experienced a substantial re/industrialization and a growing share in the World’s GDP (Baldwin, 2016). But we know little about the distributional effects of these processes.

This paper is a first comprehensive attempt to examine the long-run evolution of inequality in Poland in order to shed light on the determinants and implications of inequality. We combine tax, survey and national accounts data to provide consistent series on the long-term distribution of national income in Poland. First, we construct top income shares for the whole period from the end of the nineteenth century until today. Next, we combine household surveys and income tax data in order to provide more reliable estimates of the full income distribution in Poland from 1983 until 2015. More precisely, we use tax data on high-income taxpayers to correct the top of the survey distribution. We thus produce the first homogeneous series that offer a possibility to compare the level and evolution of income inequality in Poland both through time and across countries.Footnote 1

Figure 1 summarizes our main results on the long-run income inequality in Poland.Footnote 2 We interpret these results through the lenses of theories analysing the determinants of income inequality and the implications for economic development (Galor & Moav, 2004; Kuznets, 1955; Piketty, 2014). Table 1 provides a concise overview of Polish history since the nineteenth century and we follow the outlined periodization in our analysis throughout the paper.Footnote 3

Source: Authors’ computation based on income tax statistics. Distribution of fiscal income among tax units. Note: the Prussian Poland is the Province of Posen and West Prussia, the Austrian Poland is Galicia. For 1925–1937 Poland is the Second Polish Republic (with 1918–1939 borders), for 1945–1989 Poland is the Polish People’s Repulbic (with post-1945 borders), for 1992–2015 Poland is the Third Polish Republic.

Top 1% income share in Poland, 1892–2015.

Top income shares in Poland followed a U-shaped evolution from 1892 until today. We find that top income share followed different trajectories in the Prussian and Austrian partitions, a steady rise in the former contrasting with the stagnation in the latter,Footnote 4 which we link with the different political institutions and economic structures. The destruction of the First World War and a set of post-war shocks and redistributive polices led to a sharp reduction in top income shares. During the 1920s, however, top income shares recovered from this low-point and the Great Depression resulted in further concentration of income at the top. We document a high concentration of capital income at the top of the distribution throughout the first half of the twentieth century.

The introduction of communism led to a dramatic fall in top income shares. As documented now in many countries, the post-WWII downward trend in inequality was induced by the fall in capital income concentration. Communism signified comparatively greater shock to capital incomes relative to other countries, by literally eliminating private capital income with nationalisations and expropriations, while in addition it implied strong reduction of top labour incomes. During the remaining four decades of the communist rule, top income shares displayed notable stability at these—to some extent artificially—lower levels.Footnote 5

We analyse the transition from communism to a market economy by constructing the full income distribution (1983–2015) from combined tax and survey data. Figure 2 presents our series on the income distribution. We show that within one generation, Poland has moved from being one of the most egalitarian to one of the most unequal countries in Europe. Inequality experienced a substantial and steady rise after the fall of communism, which was driven by a sharp increase in the income shares of the top groups within the top decile. Over the whole 1989–2015 period, real income rose for nearly all income groups, but the top 1% captured almost twice as large a portion of the total income growth as the bottom 50% (24% versus 13%). The middle 40% and bottom 50% income shares experienced a similar evolution characterized by a stable fall from 1989 until the mid-2000s, and a stagnation afterwards. These results remain in contrast to the official survey-based measures, which substantially underestimate the rise of inequality since the end of communism, primarily by underestimating the top of the income distribution.Footnote 6

The highest increase took place immediately at the onset of the transition in the early 1990s and was induced both by the rise of top labour and capital incomes. However, the strong rise in inequality in the 2000s, after Poland joined the European Union, was driven solely by the increase in top capital incomes, which are dominant sources of income for the top percentile group. Today, Polish top income shares are at the level of most unequal European countries, most notably Germany and the United Kingdom, but still substantially below those documented in Russia (Novokmet et al., 2018).

The new long-run inequality series present a critical input to investigate the determinants and implications of inequality. Overall, we point to the central role of country-specific institutions and policies in shaping the U-shaped evolution of inequality in Poland in the long run. The long-run evolution of top income shares presents suggestive evidence against the ‘natural’ decline of inequality along the development path. That is, the secular fall of inequality after WW2 in Poland was not an outcome of natural economic forces innate to the development process, nor its rise after 1989 can be explained by the new ‘technological revolution’. Although a closer look at certain episodes in Polish history underlines the importance of economic forces, in particular, technological change and globalisation, we argue that their distributional impact depends on a broader institutional setting (e.g., labour market institutions such as unions, minimum wage, corporate governance; provision of public education; government transfers and safety nets, or social norms towards inequality). Our series also shed new light on the role of inequality for growth in Poland and other post-communist countries. We highlight several ways in which institutional systems have mattered regarding the way inequality affected development through accumulation and efficiency channels.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 discusses the literature on the interplay between inequality and development through the lens of the Polish distributional history. Section 3 describes data sources and methodology. Section 4 presents the trends of the top income shares since the end of the nineteenth century until the end of communism. Section 5 presents the evolution and composition of the full income distribution since 1983 until 2015 and discusses the potential mechanisms at play. Section 6 compares the estimates for Poland with other countries. Finally, Sect. 7 concludes. Additional analysis is provided in the Appendix. The details of the data and estimation are discussed in the Online Appendix.

2 Inequality and development: through the Polish lens

This paper lies at the intersection of different strands of literature looking at the interplay between inequality and growth. In what follows, we present those theoretical strands through the lens of Polish distributional history.

2.1 Determinants of inequality

This paper shows the evolution of inequality in Poland in the long run and its determinants. Here our work directly builds on the top income literature. Kuznets (1953) first constructed top income shares for the US, which served as the empirical basis of the inverse-U curve, according to which inequality first increases and then declines as a country develops (Kuznets, 1955). A huge (‘Kuznetsian’) literature subsequently emerged investigating the distributional effects of economic development. One of its features is that the evolution of inequality along the development path is primarily driven by economic forces.Footnote 7

Economists have generally discussed the distributional impact of growth through the distributional effects of factor accumulation and technical change (e.g., Bourguinon 2005). The instance of the ‘skill-biased’ technological change has figured prominently in debates discussing the recent changes in earning inequality. Analysed in the ‘demand and supply of skills’ framework, it can generate a Kuznets-type process: inequality initially rises as technological advances (also augmented by globalization) increase the demand for skilled workers, but then falls as the rest of the workforce acquire new skills and enter high-productive sectors (the ‘race between technology and education’; Galor & Tsiddon, 1997; Goldin & Katz, 2008; Tinbergen, 1974, etc.).Footnote 8 The cyclical evolution of inequality is thus sometimes seen as inherent to the development process, when growth is driven by consecutive skill- or capital-biased technical changes.

Piketty (2001, 2006, 2014) has challenged the optimistic message inherent in the Kuznets’ process. He argues that the ‘great levelling’ of the twentieth century was a historically unique episode and that there is no spontaneous fall in inequality. Instead, he has emphasized the important role of policies and institutions in shaping inequality in the long run. For example, the recent rise of inequality in countries such as the US is largely a consequence of changes in policies and labour market institutions, such as lower tax progressivity, deregulation, erosion of unions or decline in minimum wage (Levy & Temin, 2007; Piketty & Saez, 2003, etc.).Footnote 9

Overall, it has been recognized that to assess the complex effects of development on distribution, it is necessary to study the development process of individual countries. This allows us to assess the role of country-specific institutional contexts and policies in shaping inequality (e.g. Kanbur, 2000; Piketty, 2006). Furthermore, the comparative historical account provides a unique perspective from which to assess the relative importance of different factors in determining inequality. This paper is a step in this direction. We next discuss what the Polish experience tells us about the determinants of inequality in light of these theories.Footnote 10

The unique Polish distributional history highlights the central role of institutions and public policies in shaping inequality in the long run. We find that the U-shape development of inequality in Poland was critically shaped by the changes in the institutional structures, as most clearly manifested in unparalleled changes in the labour market and capital ownership arrangements which have accompanied the rise and fall of communism (Sects. 4.3 and 5.2). This presents suggestive evidence against the ‘natural’ decline of inequality along the development path as envisaged by the Kuznets process. Moreover, a broad synchronisation of top income shares in communist and non-communist countries in the long run suggests that institutional and political factors played a decisive role both in reducing inequality in the first half of the twentieth century and in inducing an upward turn in inequality since the 1980s (Sect. 6; Atkinson, 2015; Atkinson & Piketty, 2007; Piketty, 2001).Footnote 11 In this respect, the evolution of inequality in Poland may be seen as an extreme version of the inequality dynamic observed in Western countries.

This is not to say that economic forces do not matter as determinants of inequality. We indeed show that the models emphasizing the importance of market forces, in particular of technological change and capital accumulation, are useful for understanding Polish inequalities in particular moments of the country’s history. However, we argue that their distributional impact depends on a broader country-specific institutional and social context. This interaction is visible during two periods of Polish distributional history—industrialization in pre-WW2 Poland and the transformation to capitalism after 1989.

Using regional data for interwar Poland, we find patterns broadly consistent with the predictions of the upswing of the Kuznets curve (Appendix 1 and Sect. 4.2), which suggests that productivity advances shifted economic activity to cities and led to an increase in inequality. Yet, different institutional endowments inherited from the Partitions period (1772–1918) mattered for the distributional impact of the ‘first’ industrialization. For example, the legacy of ‘agrarian capitalism’ amplified inequalities in the case of former Prussian counties (Appendix 1 and Sect. 4.1). More generally, this suggests that neglecting country-specific institutions and policies presents the main obstacle in accounting for deviations from the Kuznets curve in empirical research (Kanbur, 2000; Williamson, 1991). The distributional effects of ‘classical’ industrialization cannot thus be generalized without considering a wider context (such as the general level of nutrition and hygiene, public infrastructure and education, the balance of political power, social legislation and safety nets, etc.) (Sects. 4.2. and 4.3). As a revealing case in point, the distributional impact of ‘socialist industrialization’ in Poland critically depended on its distinct institutional and socio-political features, in particular, the unique pattern of capital ownership or social policies aimed at elimination of mass poverty and improvements in healthcare (Sects. 2.2 and 4.3).

We devote special attention to the analysis of inequality determinants after the fall of communism, in particular, the role of institutional reforms, technological change and globalisation. Following the canonical ‘demand and supply of skills’ framework, we highlight the role of the demand for higher-educated workers in driving an increase of earnings inequality after 1989 (Appendix 2). We also show that a rise of top income shares, driven largely by top business incomes, is closely linked with the evolution of the capital share and the export share of GDP (Sect. 5.2). But here as well, we show that the country-specific institutional setting critically mediated the effect of market forces. This is visible in divergent inequality trajectories in Poland and Russia during the transition to a market economy, which we link with the different transition strategies (Keane & Prasad, 2002; Novokmet et al., 2018). In particular, we provide suggestive evidence for the role of minimum wage and privatization in driving the difference in the rise of inequality between the two countries (see Sect. 5.2).

2.2 The effects of inequality on growth

The theoretical literature has broadly examined the general effects of inequality on economic growth through: i) factor accumulation (investment in physical and human capital), and ii) efficiency in using factors and technology (Weil, 2013, ch.13).Footnote 12

Factor accumulation channel. The ‘classical’ approach posits that inequality is beneficial for economic growth as it shifts resources to rich individuals, who have higher marginal propensity to save, thereby leading to higher aggregate savings and higher physical capital accumulation, and hence growth (Bourguinon, 1981; Kaldor, 1957; Keynes, 1920; Lewis, 1954, etc.). The ‘modern’ approach, first advanced by Galor and Zeira (1993), argues instead that in the presence of credit market imperfections, inequality may adversely affect human capital formation and economic development. Galor and Moav (2004) have reconciled these views in the unified theory of the dynamic effects of inequality on development. In the unified framework, the way inequality affects growth depends on the relative return to human and physical capital. In the early stages of the development, when the physical capital is crucial for growth, the beneficial impact of inequality through the saving channel dominates the negative impact of inequality on human capital formation. And vice versa in the modern period when human capital is the key for development. Our series offers a possibility to assess this framework for the development process of the ex-communist countries.

According to Galor and Moav (2004), physical capital accumulation was key during the take-off from Malthusian stagnation (i.e. the Industrial Revolution; Galor, 2005; Galor & Weil, 2000). The partitioned Poland underwent a phase of classical industrialization from the mid-nineteenth century until WW1. This may be primarily seen in the rise of industry in the Congress Kingdom (e.g. textiles in Łódź, manufacturing in Warsaw; Wandycz, 1974), but also in the ‘agrarian capitalism’ in Prussian Poland. The presence of the ‘classical channel’, according to which inequality ensured necessary capital accumulation, may only be indirectly inferred from higher concentration of capital income at the top (see Sect. 4.1). Correspondingly, a shift of the political power from capital to labour after the unification of Poland in 1918 may have possibly discouraged accumulation and precipitated the sluggish interwar growth.Footnote 13 Overall, despite occurrences of industrial development, Poland was still in the first half of the 20th c. predominantly an agricultural economy. Levels of industrialization and urbanization were among the lowest in Europe (Buyst & Franaszek, 2010, T. 9.1; Malanima, 2010) and the slow economic growth implied no convergence with Western Europe (see Figs. 10 and 13).

After WW2 Poland experienced three decades of strong economic growth. The introduction of communism brought a massive accumulation of physical capital (Feiwel 1981). However, due to comprehensive nationalization of the means of production, the positive effects of inequality on aggregate saving operated through a more pronounced functional, rather than personal, inequality.Footnote 14 Higher profits, and hence higher investment, were in part ensured at the expense of the lower wage fund (and sacrifices in consumption). The beneficial effects of (functional) inequality on growth were operative because the aggregate productivity of physical capital is generally independent of its distribution (Galor, 2011; Galor & Moav, 2004). The rapid industrialization of Poland accentuated the demand for human capital due to capital-skills complementarity (Galor & Moav, 2004). In this respect, communists fostered investments in human capital, such as school construction projects, development of specialized vocational schooling, or promoted female labour participation.Footnote 15 In addition, communist reforms contributed to sweeping away feudal growth-inhibiting institutions—pervasive in Poland until well up WW2—and inducing structural change (see Sect. 4.3; Galor & Moav, 2006; Milanović, 2019; Piątkowski, 2018).

The fall of communism and the transition to a market economy amplified the complexity of the inequality-growth nexus, entailing a change in the relative returns and the way inequality affects growth. Lower inequality at the outset of the transition, with binding credit constraints, was conducive to the large expansion of tertiary education documented, which has been critical for the country to successfully adapt to the global environment and to approach the technological frontier (Galor & Weil, 2000; Goldin & Katz, 2008; Schultz, 1975).

On the other hand, the transition to a market economy entailed a renewed role of physical capital accumulation as the engine of growth. Actually, capital deepening has been one of the key contributors of labour productivity growth in Poland since the mid-1990s (see Gradzewicz et al., 2014; Rincon-Aznar et al., 2014). Indeed, Baldwin (2016) calls it re-industrialization and puts Poland as part of the global ‘Industrializing Six’. Thus, more pronounced top-end inequality in Poland, as evidenced in this paper, might have been growth-enhancing if top income groups had higher saving rates. However, opening to international capital flows might have reduced the beneficial effects of (interpersonal) inequality on growth through the saving channel.Footnote 16

Efficiency channel. Inequality may stimulate growth due to investment indivisibilities, that is, when set-up costs of new businesses are high and capital markets are highly imperfect (e.g., Aghion et al., 1999; Banerjee & Newman, 1993). Indeed, this reasoning has been often used to point to the beneficial effects of inequality for the transition countries. Privatization of state-owned enterprises was intended to channel resources to the highest-value users to improve efficiency and strengthen profit incentives (Roland, 2000). Relatedly, it has been often argued that low inequality during communism adversely affected work incentives and effort. In this respect, a decentralization of the wage setting process after communism and the resulting earning decompression—especially in the upper part of the distribution (see Sect. 4.3 and Fig. 5)—may have improved incentives and stimulated growth.Footnote 17

However, an important takeaway from the ‘modern’ approach is that there is a need for sustained redistributive policies (especially in the presence of credit market imperfections in investment in education; Aghion et al., 1999). Indeed, recent empirical research has found that (non-extreme) redistribution is not harmful for growth (e.g., Ostry et al., 2014), particularly if it promotes productive policies, such as investment in education, healthcare or infrastructure (Lindert, 2004). In contrast, higher inequality may hurt growth through the political channel exactly by impeding implementation of these kind of policies (e.g. through lobbying or corruption) and generally through socio-political instability (e.g., Alesina & Perotti, 1996; Easterly, 2001; Galor et al., 2009). Indications of the operating political channel may be inferred from the recent sharp political polarisation of Polish society (Lindner et al., 2020).

3 Data and methodology

We combine tax, survey and national accounts data to construct our measures of long-run income distribution. First, we construct new consistent series on the entire income distribution for the 1983–2015 period. More precisely, we correct the top of the household income survey distribution with administrative data on high-income taxpayers. The methodology follows the Distributional National Accounts (DINA) guidelines (Alvaredo et al., 2016). For the earlier period, we focus on top income shares due to the absence of viable household survey data. We combine income tax and national accounts data to construct top income shares for the whole period from the end of the nineteenth century until today. Online Appendixes OA.1–OA.3 discuss the data and methodology in detail.

3.1 Data sources

Income Tax Statistics in Poland. We first present data sources on income tax statistics, which present the central block for the construction of top income shares and the distributional national accounts. The first modern income tax in the Polish lands was established by the Prussian (1891) and Austrian Empires (1898) during the Partitions of Poland. Both Prussian and Austrian income tax statistics provide tabulations of income taxpayers in a regional breakdown, which has allowed us to construct top income shares for provinces with significant Polish population (the Province of Posen and West Prussia in Prussia; Galicia in Imperial Austria). There is no tax data for the Russian Partition (the Congress Kingdom), as comprehensive income tax was never introduced in Imperial Russia.

In 1924, the newly independent Poland introduced a unified progressive income tax for its whole territory. Detailed interwar income tax statistics were published separately for unearned income (fundowany) and earned income (niefundowany), organised by a large number of income brackets containing the number of taxpayers in each bracket and their corresponding tax obligation.

The communist government was established in 1947, so the interwar income tax system was still in use for several years after WWII, and the income tax tabulations are available for 1945–7. However, with the waves of nationalisation and the elimination of the private sector in the late 1940s, the personal income tax de-facto disappeared along with tax statistics. Instead, we combine different data sources to construct top income shares during the socialist period. As our starting point, we look at the detailed earnings statistics, published annually since 1956. The statistics covered all workers in the socialised sector, which accounted for the greatest part of the labour force (Atkinson, 2008; Atkinson & Micklewright, 1992). Published tabulations range workers in a large number of brackets according to the size of their gross earnings, providing, as a result, a detailed insight into both the upper and lower tail of the earnings distribution.Footnote 18 Next, we assume that top earnings in the earnings statistics are representative of the right-end tail of the income distributionFootnote 19 (more precisely, we focus on brackets covering 5% of individuals with highest earnings), while the remaining adult population is bulked into the bottom bracket (the bottom 95%). We attribute the remaining income from self-employment and social transfers to the bottom bracket.

For the post-communist era, income tax data come from the annual reports on the settlement of the personal income tax (PIT). The tax administration has published annual income tax tabulations since 1992. Tabulations are organised by income ranges that correspond to tax brackets as defined by the progressive tax schedule, with each bracket containing the number of taxpayers, their total income, deductions and the corresponding tax obligation. Due to the limited progressive structure of Polish PIT, the number of brackets in published statistics has been relatively small (generally equal to three for the post-communist period), with more than 90% of taxpayers located in the bottom bracket. As a result, although a great majority of the population is subject to PIT, the available income tax tabulations cannot be used to recover the entire income distribution. Instead, we use information on high-income taxpayers in combination with the household survey data.

Household income surveys. A Household Budget Survey (HBS) has been regularly conducted in Poland since 1957. Until 1972, it covered only employees in the socialized sector, excluding agriculture. Thereafter, it was conducted for four types of households: worker, mixed, farmer, and pensioner households (Atkinson & Micklewright, 1992, pp. 258–263). The survey underwent important changes after 1990, becoming fully representative of the population (Kordos et al 2002; Keane & Prasad, 2002; Milanović 1999).

For the 1980s, we use the Polish Household Budget Survey (HBS) data from Atkinson and Micklewright (1992, Tables PI1 and PI2). The authors provide tabulations of the individual distribution of household income per capita by combining the distribution of income for four types of households from the official HBS reports.Footnote 20 The tabulations are organized by eight income groups, providing in each case the number of individuals and the mean income. For the 1992–2004 period, we use harmonised HBS microdata from the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS). Finally, for the period 2005–2015, we use the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). We harmonize the definition of income and the unit of analysis across the surveys.

National accounts data. We construct the total income and population controls based on the definition of income and the tax unit in the tax code. For the 1992–2015 period, we use National Accounts data published by the Central Statistical Office of Poland (GUS). For the interwar period we rely on historical series published by Kalecki and Landau (1934) and series constructed by the Maddison project (Bolt et al., 2018). The data for the period before World War I comes from the Prussian and Austrian censuses, yearbooks and various monographies.

3.2 Methodology

There have been long-standing attempts to combine various data sources in order to produce consistent series on the distribution of national income over time and across countries. One of the pioneering works was done on Poland by Jan Wiśniewski (1934), who combined numerous data sources, such as income tax data, occupational ‘social tables’, and census data, in order to estimate the income distribution in Poland in 1929. In recent years, the large body of empirical work on the income distribution has estimated long-run series of top income shares, by combining income tax tabulations with national account totals for the population and the income, and using Pareto interpolation techniques. The methodology was pioneered by Kuznets (1953) and recently advanced by Piketty (2001, 2014), Atkinson and Piketty (2007, 2010), among others. We produce top income shares in Poland for the whole period from 1892 until 2015. All details are provided in Online Appendixes OA.1–OA.3.

Although tax data has proven to be especially useful to chart the long-term dynamics at the upper end of the distribution, they are silent on the remaining part of the distribution. On the other hand, it is well documented that household income surveys underestimate top incomes, which can critically impact overall distributional measures and misread the general trends in the income distribution (Atkinson et al., 2011; Piketty & Saez, 2003). Consequently, there have been various attempts to combine administrative tax and survey data to obtain more reliable estimates of the income distribution (e.g. Burkhauser et al., 2016; Piketty et al., 2018). Major progress in this direction has been made by the WID.world project. We follow its Distributional National Accounts guidelines (Alvaredo et al., 2016; Piketty et al., 2018) in the construction of comprehensive measures of income distribution in Poland.

The general methodology we use to combine survey and fiscal data consists of two basic steps. In the first step we use the raw survey tabulations and generalized Pareto interpolation techniques (Blanchet et al., 2017) to estimate series on the distribution of survey income by generalized percentiles (g-percentiles). In the second step, we use tax data on high-income taxpayers to correct upwards the survey series and obtain corrected estimates of the distribution of fiscal income. We assume that survey data provide a reasonable description of the income distribution below the 85th percentile. On the other hand, we take that tax data is accurate above the percentile corresponding to the first available income threshold in tax tabulations (generally corresponding to the 95th percentile). We then apply the piecewise-linear correction factors f(p) between these percentiles.Footnote 21

In our accompanying work in progress (Bukowski et al., 2021) we show that the above methodology produced series on income inequality remarkably similar to those based on the registry database of the universe of individual-level tax returns for the period 2004–2017 (see also Kośny, 2019 for Lower Silesia).

Unit of observation. The unit of observation is the individual aged 20 or more. Household income in the survey is equally split between adults who belong to the same household. We should bear in mind that when combining survey and tax data we make implicit assumptions that high-income individuals in tax data are either singles, or that spouses have reported equal income. Since the option of joint filing for couples is widely used (the tax unit in the tax code is individual), it is reasonable to assume that eligible high-income taxpayers file a joint declaration by equally splitting their income in order to reduce their tax obligation. According to the PIT reports, the majority of eligible taxpayers used the joint taxation.

A further issue is that the homogeneity over time can be impaired by changes in the tax unit in the tax code. While the data for the communist and post-communist period relates to individual units, the tax unit in Austria, Prussia, and in interwar Poland was the household, with the total income of household members ascribed to the head of the household.Footnote 22 The total number of households is estimated as all adult above 20 years of age minus the number of married females. The corresponding data is taken from population censuses and annual figures from the statistics on the movement of the population, and linearly interpolated for missing years.

Definition of Income. We focus on the distribution of pre-tax income, which refers to the sum of all income flows going to labour and capital, plus pensions but before other taxes and transfers. This income concept corresponds to the concept of fiscal income reported in the income tax statistics (Alvaredo et al., 2016; Piketty et al., 2018).Footnote 23

Taxable income in both Austria and Prussia, as well as in the interwar period was quite broad and allowed very few exemptions. The post-communist tax data include income from employment, pensions, income from non-agricultural business activity and special agricultural activity, income from self-employment, rental income and income from other sources.Footnote 24 We account for the changes in the tax law, which modify the definition of income. There were no major reforms of the tax system during the interwar period. However, the post-communist tax law has been amended several times since 1992. Most importantly, since 2004 income from non-agricultural business activity (further referred to as business income) can be taxed separately using a newly introduced flat tax. See Online Appendix OA.1.7. for all details of how we combine statistics on business income taxed at linear rates and income taxed using the progressive scale.

As noted, when joining the survey and tax data, we produce the distribution of fiscal income. A distinction needs to be made between fiscal income and national income, which is defined as GDP minus consumption of fixed capital plus net foreign income (SNA 2008). A major difference is due to the fact that the national income includes in addition tax-exempt capital income, such as undistributed corporate profits or imputed homeowners’ rents. We do not impute these items due to data availability, but, in general, it has been found that the fiscal correction (using income tax data) accounts for the bulk of upward correction of raw survey inequality, and further adjustment for the distribution of tax-exempt capital income has been shown to be of limited importance (e.g. Novokmet et al., 2018). Most importantly, correcting income distribution by imputing corporate retained earnings is less important in Poland, because business income is predominantly taxed according to the pass-through concept and hence attributed to individuals (Alstadsæter et al., 2017; Kopczuk, 2012).Footnote 25 Alstadsæter et al. (2017, T.1) show that Poland has by far the highest share of employment in pass-through entities in Europe. Finally, in order to allow an international comparison, we scale fiscal income distribution up to the national income totals by proportionally upgrading thresholds and average incomes for each percentile of the fiscal income distribution.

4 Top income shares in Poland 1892–1989

This section presents the evolution of top income shares in Poland from 1892 until 1989. Over this period, Poland experienced dramatic economic and political transformations. Until the 1980s, the real income per adult in Poland was around half of the income in Western Europe (Fig. 13), but the gap widened during the last decade of the communist period.

4.1 Partitioned Poland and World War I

The three Partitions displayed different levels of economic development as well as specific institutions and different social conditions.Footnote 26 Only Prussia and Austria introduced a comprehensive income tax in the Polish lands. We construct top income shares for the Austrian and Prussian partitions. Unfortunately, we omit the Russian partition as there are no comprehensive tax sources available. However, in Online Appendix OA1.3, we discuss alternative estimates of inequality in the Congress Kingdom.

Figure 1 shows the top 1% income shares in Poland from 1892 until today (see Online Appendix Tables OA6-OA9). We start with the Prussian Partition. Following a moderate rise from the 1890s until 1914, the top percentile increased sharply by 7 percentage points after the outbreak of World War I. The overall rise in top income shares was mostly driven by very high-income shares (see Online Appendix Figures OA3 and OA4, Table OA6) and almost exclusively due to a rise of very high incomes in rural areas, while shares of urban incomes remained stable throughout the whole period under consideration (Fig. 15). We believe that an explanation for the documented rise of top income shares in the Prussian partition should be sought in the growth of capitalist agriculture and the development of related industries (such as distilleries, sugar refineries or machines for agriculture, etc.) (Dumke, 1991; Grant, 2005). Diffusion of advanced farming techniques, related to an adoption of capital-intensive industrial crops such as sugar beet, contributed to a spectacular improvement in productivity in the Prussian partition between 1882 and 1907, surpassing that in the rest of Germany (see Online Appendix Figure OA5, Grant, 2002). Productivity advances were dominantly captured by the top of the distribution because of relatively high land inequality—an outcome of the Prussian land reforms, which favoured larger estates at the cost of smallholdings (Eddie, 2013; Grant, 2005; Mieszczankowski, 1960). Large estates were the driving force behind the structural transformation of agriculture in East Elbia, in what has often come to be generalised as the ‘Prussian’ road to industrialisation (Lenin, 1908). However, the causation might have run the other way, from inequality to growth, notably by alleviating accumulation constraints in line with the “classical channel” (see Sect. 2).Footnote 27

Top income shares in the Prussian partition soared during World War I (Fig. 1 and Online Appendix Figures OA3-OA4, Table OA6). The economic environment favoured the capital owners, especially due to the wartime demand for armaments and food. The Allied blockade was the root cause of the German food problem, as it caused a plunge in food imports (Hardach, 1977; Ritschl, 2005). Food shortages led to a surge in prices, bringing, in turn, extraordinary profits to agricultural producers, which were proportionally more concentrated in Prussian Poland.

The Austrian Partition (also known as Galicia) was economically the least developed of the three ‘partitioned’ Polish regions.Footnote 28 Top income shares in Galicia showed no clear trend in the two decades preceding WW1 (Fig. 1). The top 1% income share increased by almost 3 percentage points in the short period from 1898 until 1901, when it peaked at 14.3%. Afterwards we observe a falling trend during the years preceding WW1. We believe that top incomes in Galicia were mainly an urban phenomenon, given the backwardness of its agriculture and the notoriously poor living standards of the rural population—overwhelmingly living at the bare subsistence level (‘Galician poverty’; Bujak, 1908; Szczepanowski, 1888). As we look below, the rural–urban income gap figured prominently during the interwar period. Among the interwar Polish counties, those located in Galicia were characterized by the highest correlation between urbanisation ratio and top 1% income shares (see Appendix 1). Further, modest industrialization in Galicia since the end of the nineteenth century had an important resource-export dimension (crude oil and salt mining; Frank, 2005), possibly entailing a relatively larger importance of non-tradable services in cities (e.g. commerce or personal services; Gollin et al., 2016).Footnote 29

The positive relationship between inequality and growth may be postulated both for Austrian and Russian industrialization (Table 3 shows the positive role of urbanisation and industrialization for counties in the former Russian partition during the interwar period; see Appendix 1). Conceivably, inequality tendencies were further strengthened as the accelerating rate of capital accumulation was accompanied by the ‘surplus’ of unskilled labour amid a strong population increase during the Post-Malthusian phase (further reinforced after the serf emancipation in Austria in 1848 and especially in Russia in 1864).Footnote 30

4.2 Interwar Poland

The unification of Poland in 1918 is one of the pivotal events in Polish history. Poland was established on the world map after 123 years under foreign dominions. However, this century-long dream had to be realised in quite a tumultuous atmosphere of economic crisis, broken international trade, and recovery from the massive destruction and human losses of the Great War.

Our starting point in the interwar period (1924) coincides with the lowest documented point in top income shares during the existence of interwar Poland, with the share of the top percentile slightly above 8% (Fig. 1). There are several arguments in favour of the lower top shares in the first half of the 1920s. First, Poland was among the countries that suffered the greatest losses during the First World War, both in the number of human casualties as well as in the extent of physical destruction (Landau, 1968). The deleterious effects of shocks to capital income in the interwar period are now well documented as the main reason behind the secular fall in top incomes initiated after WWI (Piketty, 2001; 2003).Footnote 31 Next, the risk of political radicalization and the communist upheaval pressured the new leadership of Poland into passing new social legislation, such as the eight-hour working day, trade unions or the right to strike (Derengowski, 1930; Sztrum de Sztrem, 1922; Wolf, 2007). Further, various anti-capital policies were introduced, including a sharp increase in tax progressivity and heavier taxation of capital than labour (including a one-time capital levy).Footnote 32 Industrial capital tied up in export sectors especially suffered from the loss of the large and protected Russian market and the Polish-German trade war of 1925. The currency stabilization in 1923 further negatively affected the international competitiveness of Polish products, while another great shock was hyperinflation.Footnote 33 Generally speaking, the post-war situation worldwide signified altogether a new page in the distributional history in comparison to the pre-WW1 political and social setting (e.g. Keynes, 1920; Piketty, 2014; Scheidel, 2017; Scheve & Stasavage, 2016). Thinking in terms of predictions of the ‘physical capital regime’ in the unified framework of Galor and Moav (2004), it is interesting to ponder to what extent the distributional conflict accompanied by a shift of the political power from capital to labour discouraged capital accumulation and thus precipitated the sluggish interwar growth (Fig. 13).Footnote 34

The following six years, however, saw a continuous rise in the top percentile share and reached almost 11% in 1930. The economy eventually stabilised in 1926, and the country experienced three years of steady growth, halted only by the advent of the Great Depression in 1929. The economic recovery brought better prospects for top incomes, which experienced a strong increase in the late 1920s.Footnote 35

However, when the tax data become available in 1935, the series on top income shares re-emerged at 15%, which corresponds to its secular peak in the time of peace. All top income groups saw rising shares in this period, suggesting a rising dispersion between the top and the rest of the distribution (e.g. P0-99, Online Appendix Table OA7). Accordingly, it is plausible that this development indicates a deteriorating position of Polish farmers relative to other social groups. Almost two-thirds of the population was made of small farmers and it was agriculture that was most adversely affected by the Great Depression, in the first place due to a strong fall in agricultural prices (Landau, 1963). In contrast, the fall in industrial prices was much less steep due to rapid cartelization, which safeguarded industrial profits at the top.Footnote 36 The deflationary trend was, on the other hand, beneficial to high-salaried employees that were able to keep their jobs due to rigid salaries, making this group a relative winner behind this development (Kalecki & Landau, 1935; Landau, 1933, Fig. 16).

The Great Depression led to a differential income fall for different top groups (see Fig. 16). The top 0.1% saw a proportionally stronger fall at the start of the crisis (1929–1931) than the lower groups in the top percentile. Yet, in 1935 (unfortunately, there is no data for three years after 1931) we find that top groups had managed to retain their relative standing. Plausibly, the rapid cartelization should be identified as the main tool allowing top incomes to steer through the crisis successfully, and the main beneficiaries should be searched for among the capital income recipients. Figure 3 shows the composition of top income groups in 1929 between earnings and other sources of income (defined in the tax statistics as ‘unearned’ income, roughly corresponding to the broad definition of capital income). Groups below the top percentile, such as the top 5–1%, were mainly composed of earnings. The importance of earnings, however, decreases with income rank. For the top 0.1% group, unearned income made up as much as 80% of the total income.

Source: Authors’ computation based on income tax statistics and Wiśniewski (1934)

The composition of the top 5%, Poland in 1929.

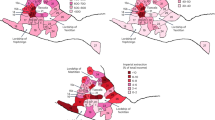

Further insights could be obtained by looking at the spatial distribution of county-level top income shares in Poland.Footnote 37 Figure 4a presents the map of Polish counties in 1927 and the contribution of each county to the aggregate national top 1% income share. We find that the most significant contributor to the national top percentile is the size of the local economy (e.g. Warsaw, Łódź and Lviv contributed with around 40% of all top percentile constituents) (see more details in Appendix 1). Figure 4b displays county-level top 1% income shares (calculated using the county control population and total county income). The dashed line marks the former borders between the partitions. The geographic distribution of top income shares has a donut-shape, with high levels at the edges of interwar Poland and relatively low in the centre. The largest inequalities are in the former Prussian Partition (the west) and the eastern parts of the former Russian Partition (the east). The picture is less clear for the former Austrian Partition (the south and south-eastern parts), where there are no clusters of counties with high top income shares.Footnote 38 Appendix 1 looks at the determinants of the county-level top 1% income share. We find that the county-level top 1% income share is positively associated with urbanization, employment share in industry and agriculture, and land inequality. However, we document heterogeneity in the importance of these factors across the former partitions of Poland (e.g. the importance of land inequality and the agricultural employment in the former Prussian partition is indicative of the ‘agrarian capitalism’). We also analyze a joint distribution of income and inequality for the rural and urban counties and find patterns broadly consistent with the predictions of the upward part of the Kuznets curve.

4.3 Communist Poland

In theory, the distribution of income under a socialist state should be based on the rule “from each according to his ability, to each according to his labour” (Atkinson & Micklewright, 1992; Marx, 1875). The rule does not imply an inequality-free society, as long as production concerns are pressing. In practice, however, the introduction of communism in Poland and other socialist countries led to a dramatic reduction in income inequality. The communist reforms signified an unprecedented change in the institutional framework, as manifested in the abolition of the private ownership of the means of production and the comprehensive reorganization of labor market with the direct bureaucratic control of employment and wages. The communist accession to power was further accompanied by the comprehensive redistribution of income and wealth, as well as the promotion of egalitarian ideology (e.g. Bergson, 1944; Kornai, 1992).

The post-war development of top income shares clearly reveals a secular fall in inequality. Right after the Second World War, in 1946–7, we find top income shares at the level of 9%—a significant fall from the level of 14.6% in 1936 (Fig. 1). In order to understand this decline, one needs again to ascertain a development at the ‘bottom’ of the distribution. The post-WW2 years saw a relative improvement in the living conditions of the rural population in comparison to the devastating experience of the Great Depression. This came about in the first place through rising prices of agricultural products, large land redistribution, debt release and new social legislation, such as the increased availability of education in the countryside (Landau & Tomaszewski, 1985). These reforms also contributed to sweeping away feudal growth-inhibiting institutions, pervasive in Poland until well into WW2, and induced structural change (Milanović, 2019; Piątkowski, 2018; see also Galor & Moav, 2006; Galor et al., 2009).Footnote 39

However, a decline in top concentration also ensued as communists strengthened their rule in the country, which led to an almost complete expropriation of capital income by the state.Footnote 40 The most radical legislation in the direction of nationalisation was passed in 1947. In the succeeding years, during the so-called Battle for Trade (Bitwa o handel), even the majority of small shops and crafts were nationalised. The next decisive episode was the currency reform in 1950 that virtually confiscated all personal financial wealth.

As a result, labour income and the wage setting process become the main determinants of the interpersonal income distribution in a socialist society. Indeed, Atkinson and Micklewright (1992, p. 128) document that in socialist Poland “the changes [in income distribution] over time mirror those in the earnings distribution”.Footnote 41 The wage setting process was largely centralized, with a limited role for incentive schemes. The wage structure across occupations/positions was used as a policy tool, for instance, to provide incentives for people to invest in particular skills, to stimulate the economy by widening earning differentials or to calm social dissatisfaction by narrowing them (Atkinson & Micklewright, 1992; Flakierski, 1986). In addition, bonuses were given to establishments whose performance was higher than expected. In practice, however, the wage levels were often more dependent on the political power of workers, managers and industry groups than on productivity (Brus, 1974).

Figure 1 depicts the evolution of top 1 percent income share during the communist period (see Online Appendix OA.1.6 for more details on the methodology). The inequalities slightly trended downward from 4.9% in 1956 to 3.4% in 1988, and the average level in this period is roughly half of the total top income shares in 1946 or 1992. Figure 5 presents the upper part of the earnings distribution, showing the evolution of the 90th percentile (expressed as a proportion to median) from the late 1920s until today. The evolution of wage ratios is more volatile than the top income share, yet the relative levels and trend are similar. It can be clearly seen that the upper tail inequality was substantially lower during communism than in the interwar period. The decline is further corroborated by the newly collected evidence on the wage distribution of manual workers. The figure shows a considerable upper tail inequality for manual industry workers in interwar Poland (the same is documented for manual workers in Warsaw) and a sharp decline after WWII.

Source: Own construction: 1921–1949 and 2008–2016, and for manual workers 1956–1965; other years: Atkinson, 2008; Atkinson & Micklewright, 1992; Rutkowski, 2001; (see Online Appendix OA.3). Note: 1955–1989: monthly wage for employees in socialized sector (1956–1970: gross monthly wage; 1970–1988: net monthly wage), 1992–2016: gross monthly wage; the estimate for all workers in 1929 excludes employed in agriculture

The upper part of the earnings distribution in Poland (90th percentile as proportion of median), 1919–2015.

Kalecki (1964) and Beskid (1964) show that earnings compression was primarily caused by a decline in premium between white-collar and manual workers. The fast industrialisation and urbanisation significantly improved living conditions of low and middle-income manual workers. But it should be remembered that there was a general reduction in skill differential, regardless of “collar denomination”.Footnote 42 Figure 5 conveys that a part of the decline in earnings inequality is to be attributed to the wage compression among the manual workers.

The Communist government used institutional factors, such as unionisation or centrally determined wages and prices, to control real wages. During the early years of communism, exceptional power was given to the high-level managers, which increased within-firm wage dispersion (Brus, 1974). Popular dissatisfaction was growing and culminated in massive and violent protests of workers in Poznań in 1956. The Party reacted by expanding and giving semi-independence to unions, resulting in a decline of the wage decile ratio after 1956. Notably, the P95/P50 ratio falls more abruptly than the P90/P50 (Online Appendix Figure OA10), possibly owing to the decline in the power of high-level management. Giving too much power to unions, however, was also threatening the position of the Communist government. The “thaw” of 1956 ended in the early 1960s, when the Party turned towards a more centralised economy and scrapped the independence of workers’ bodies, leading to a period of modest growth in wage dispersion.

Low labour productivity was a plague of the socialist economy in the 1960s (Flakierski, 1986). The Party reacted in the early 1970s, with a set of limited marketization reforms, which would increase worker incentives by directly linking their wages with output. It is hard to assess whether this policy had any effect on productivity, as it was also a period of foreign loan-financed consumption growth. What can be seen, however, is that wage inequality entered a decade of continuous growth, driven by the growth of within-industry dispersion and to a lesser extent by a shift in industry composition (Flakierski, 1986).

A marked tension between efficiency and equity concerns, as a reoccurring feature of the socialist economy, became again pronounced in the early 1980s. The previous decade’s precedence given to efficiency was followed by the pronounced egalitarian demands of the “Solidarność” movement. A remarkable fall in the wage ratios should be in part attributed to government policies in response to the demands of the Gdańsk Agreement (Atkinson & Micklewright, 1992; Flakierski, 1986).Footnote 43 However, this “honeymoon of egalitarianism”, in the words of Flakierski (1991, p. 99), was short-lived and the dispersion increased again after 1982.Footnote 44

Next, we briefly discuss specific ways how inequality impacted growth through factor accumulation during socialist Poland (Sect. 2.2.). Poland experienced stronger economic growth in the three post-war decades (Fig. 13). It was higher functional inequalityFootnote 45 that sustained socialist industrialization. Higher profits, and hence higher investment, were in part ensured at the expense of the lower wage fund.Footnote 46 At the same time, it may be surmised that substantial efforts to end mass (rural) poverty and improvements in healthcare ensured that hard work was performed during industrialization, and that malnutrition did not adversely affect the return to capital (Fogel, 1994; also Voigtländer & Voth, 2006). In addition, the rapid industrialization accentuated the demand for human capital due to capital-skills complementarity (Galor & Moav, 2004). Communists fostered investments in human capital in response, such as huge school construction projects, development of specialized vocational schooling, or promoted female labour participation.

However, there are qualifications to the above-mentioned features of communist development. It is now clear that a pronounced emphasis on physical capital accumulation, as practiced in communist countries (‘capital fundamentalism’), subsided over time (for alternative reasons see Allen, 2003; Easterly & Fischer, 1995; or Weitzman, 1970) and higher (forced) investment ceased to translate into higher growth (due to various ‘barriers and ceilings’ as posited by Kalecki).Footnote 47 Further, it may be conjectured that centrally-determined wage control suppressed returns on education, which led to suboptimal individual investment in education.

Finally, we must consider the meaning of monetary inequality during communism, as summarized by our measures. Given the potential distributional implications of well-known non-monetary features of the socialist economy—such as shortages and queueing, widespread consumer price subsidies and price controls, extensive social benefits in kind, or various non-wage benefits of the communist elite, among others (Bergson, 1984; Atkinson & Micklewright, 1992, c.6)—it may be asked to what extent monetary inequality reflected the true inequality of living standards. Most importantly, the varying importance of non-monetary aspects of inequality could bias inequality comparisons over time and across countries.

Notwithstanding the importance of the distortions mentioned, the consensus reached by authorities has been that money incomes were the most important welfare dimension in the socialist economies (Atkinson & Micklewrigth, 1992; Bergson, 1944, 1984; Milanović, 1998; Rutkowski, 1996, etc.) and that monetary indicators may be taken as indicative of the broad development in living standards. We do recognize them as imperfect, but as pointed out by Bergson (1984, p. 1057) “the ideal is hardly realized anywhere”. Moreover, biases tended to balance on average, leaving the overall inequality largely unchanged (Milanović, 1998).Footnote 48 Specifically, when it comes to (questioning) the reality of the increase of inequality in Poland during the transition, Rutkowski concludes that “biases seem to be of the second order and do not alter the main results” (1996, p. 91; Atkinson, 2008). In Online Appendix OA 1.6.2 we discuss in length the limitations and different interpretations of the official data on income distribution during the socialist period.

5 The full distribution of income in the post-communist Poland

5.1 The evolution of income inequality, 1983–2015

In this section we present the evolution of the full income distribution in Poland during the transition from communism to a market economy. This was a period of strong economic growth, re-industrialization and integration into the global economy. Poland has narrowed the income gap with Western Europe (Fig. 13), and today is considered by the World Bank as a high-income country.

Our new series on the evolution of income inequality in Poland show that official survey-based measures strongly underestimate the level of income inequality in Poland. In the same manner, our results suggest a notably higher increase in income inequality in Poland since the end of communism until today. The largest increase in income inequality occurred in the early 1990s, particularly between 1993 and 1995. The top 10 percent income share increased from levels around 22–23% in the 1980s to 25% in 1992–1993, and then jumped to 30% by 1995 (Fig. 2). This rise was accompanied by a fall in income shares of the middle 40 and of the bottom 50 percent. These groups experienced a roughly commensurate fall in income shares of around 5 percentage points between 1989 and 1995. Subsequently, we observe a steady rise in inequality, especially between 2003 and 2008, which has also been induced by the rising share of the top decile.

It is important to note that this rise has been altogether overlooked by the official survey-based measures (Fig. 6). Between 1989 and 2015, the top 10 percent income share rose from levels slightly above 20% in the 1980s up to 35% in 2015, as opposed to around the 26% suggested by surveys. In the same period, the top 1 percent income share more than tripled, rising from around 4% to 13%, as opposed to the 6% suggested by surveys (Online Appendix Figure OA13).Footnote 49 Overall, these results show the importance of correcting the upper end of the distribution in the survey data.

We next consider distributional effects of the transition in Poland by looking at the growth experience of different income groups. Over the 1989–2015 period, average real national income per adult has increased by 73%, or at about 2.1% per year. Overall, there has been a notable increase in the living standards of the Polish population since the fall of communism (especially when the grave stagnation of the 1980s is taken into account). However, this growth has not been equally shared. Table 2 shows that real incomes of the top 10 percent increased by 190% (or 4.2% per year) and of the top percentile by 458% (or 6.8% per year). On the other hand, the income growth of the bottom 90 percent has been much more modest: the bottom 50 percent experienced a 31% increase (1% per year) and the middle 40 percent a 47% increase (1.5% per year) in their real income. The finding that real incomes of the Polish bottom 50 percent have increased, but at the relatively lower rates, is consistent with the finding of Milanović and Ersado (2012) that in the former transition countries growth has been disequalizing in relative terms but increased absolute incomes of the bottom deciles. Table 2 also shows that the top 1 percent has captured almost twice as large a portion of the total income growth as compared to the bottom 50 percent group (24% versus 13%, respectively).

5.2 Accounting for the rise of inequality after 1989

In this section, we discuss (in chronological order) the most important forces driving the rise of inequality after 1989. The ‘return’ to a market economy may be seen as a reversal of the process of communist equalisation, manifested in comprehensive labour market liberalization and the privatization process. Economic forces consequently assumed a more important role in determining inequality, yet their distributional impact was critically mediated in a complex interaction with the specific institutional and political context. We show that a technology-driven demand for an educated workforce and globalisation contributed to the growing earning and income inequalities. However, an even stronger rise in inequality during the transition was precluded by extensive social transfers, higher minimum wage or more gradual privatization.

Rising earnings dispersion has been commonly identified as the main cause of rising income inequality in Central Eastern European countries during the first years of transition (Flemming & Micklewright, 2000; Milanović, 1998; Mitra & Yemtsov, 2006). The rise of earnings dispersion in Poland can be clearly seen in Fig. 5 above. The rising educational premium, triggered by the decentralisation of the wage setting process, has been usually singled out as the main cause of rising wage inequality in Poland (e.g. Keane & Prasad, 2006; Letki et al., 2014; Rutkowski, 2001).Footnote 50 In Appendix 2, we look jointly at the trends in the relative returns to education and the supply of educated workers, and infer about trends in the relative demand for educated workers (Goldin & Katz, 2008). Indeed, the university wage premium sharply increased from 35% in 1986 to 107% in 2007, which, together with the continual increase in the supply, implied a strong growth in the demand for educated workers, especially from emerging sectors such as financial, business and IT services. However, after the mid-2000s the supply growth outpaced the demand shifts and the wage premium declined to 78% in 2016. Consequently, wage inequality stagnated, although income inequality continued to grow (see Fig. 5, and Online Appendix Figures OA9-OA12).

Overall, a strong increase of educational attainments in Poland has often been singled out as the critical factor for the successful Polish transition. Consistent with the ‘modern channel’, lower inequality at the outset of the transition, with binding credit constraints, was conducive to the documented large expansion of tertiary education, which has been critical for the country to successfully adapt to the global environment and to approach the technological frontier (Galor & Weil, 2000; Piątkowski, 2018).

More extensive and well-targeted social transfers toward low-income groups and a generous minimum wage have often been seen as the most important mechanism in precluding a sharp rise in inequality in Poland during the transition (Keane & Prasad, 2002; Mitra & Yemtsov, 2006).Footnote 51 In this respect, the contrasting development of the bottom 50% of income shares in Poland and Russia is particularly striking (Fig. 20). The bottom 50% share was around 30% of national income in both countries in the 1980s. But, while the bottom 50% share in Russia more than halved between 1991 and 1996, its Polish counterpart experienced a relatively moderate decline during the same period. This development mirrors a divergent development of institutional and political factors during respective transitions in Poland and Russia, in particular, of transfer payments and minimum wage (see Fig. 19 and Online Appendix Figure OA15). Moreover, Keane and Prasad (2002) have argued that these social policies ensured social stability and provided the general political support for the market reforms and enterprise restructuring in Poland.Footnote 52 Further, the different privatization strategies pursued—‘big-bang’ in Russia versus more gradual in Poland—have often been highlighted as an important source of the documented divergence of income and wealth inequality trajectories in two countries.Footnote 53

We provide suggestive evidence for the differential role of minimum wage and privatization for the evolution of inequality in Poland and Russia. We construct a panel of four countries (Poland, Russia, Hungary and Czech Republic) from the early 1990s until 2015. Next, we regress income shares (top 10%, middle 40% and bottom 50%) on minimum to average wage ratio or the EBRD privatization indicator, and a set of country fixed effects and year fixed effects, which together capture all country-specific time-invariant determinants of inequality and all common annual shocks to income shares. Figure 7a presents the estimated non-causal change in income shares due to the actual change in the minimum to average wage ratio (the privatization indicator) between 1989 and 2015 (2000)Footnote 54 (i.e. we estimate the effect of 1 pp increase of the independent variable and multiply it by the change of this variable between 1989 and 2015/2000). For the sake of brevity, we report only results for Poland and Russia (see Online Appendix Figure OA18 for the results for Czech Republic and Hungary). The results show that the actual changes in minimum wage in these two countries have opposite non-causal predictions for the evolution of inequality. The rise of minimum wage in Poland, ceteris paribus, is associated with the rise of bottom 50% by 3.6 pp, middle 40% by 0.4 pp and analogous fall of top 10% by 4 pp. In Russia, the predicted changes are opposite and show a 4 pp fall of bottom 50%. The predicted change in income shares due to the actual changes in privatization are also in line with our expectations. Strikingly, the rise of the indicator between 1989 and 2000 predicts a rise of top 10% by 2.1 pp in Poland, but more than 15 pp in Russia, and a fall of bottom 50% by 0.9 pp and 13.5 pp respectively. Overall, a markedly different transition experience in Poland and Russia suggests that there was no predetermined trajectory of inequalities during the transition. It clearly shows that policies and institutions play an important role in shaping inequality.

Source: EBRD transition indicator: EBRD. Minimum wage ratio, capital share and export share: OECD. Income share: authors’ computation and WID. Distribution of national income among equal-split adults. Note: the upper left (right) panel shows the estimated non-causal change in income shares due to the actual change in minimum wage to average wage ratio (EBRD transition indicator) between 1989 and 2015 (2000). The bottom left (right) panel shows the estimated non-causal change in income shares due to the actual change in capital share (export share) between 1995 (2000) and 2015. The estimates are constructed from country-specific correlation coefficients between the analysed factor and each income share, estimated from a panel fixed effect country-level regression (PL, CZ, HU, RU (upper panel), DE (bottom panel)), which includes a full set of year fixed effects. The bars are calculated by multiplying the estimated coefficients for each income share and country by the actual change in the independent variable. Online Appendix Figure OA18 presents the results for Czech Republic and Hungary

a The predicted (non-causal) effect of the cumulative change in minimum wage and institutional transition on income shares in Poland and Russia. b The predicted (non-causal) effect of the cumulative change capital share and export share on income shares in Poland and Germany.

The recent rise in inequality in Poland has been driven again by the increase in top income shares. The top 10 percent share has steadily increased since the early 2000s and reached levels of around 35% by 2015 (Fig. 2). To understand better this development, we turn to the income composition for top groups. Figure 8 shows that higher top income groups have been mostly composed of business income, while earnings have dominated for lower top groups constituting the top decile, such as for the ‘next’ 4%. Business income combines both the capital and the labour component (Kopczuk & Zwick, 2020),Footnote 55 but in the Polish context, it is plausible that business income at the top reflects in large part the return to capital (Alstadsæter et al., 2017; Kopczuk, 2012; see Sect. 3).

Source: Authors’ computation based on income tax statistics; Distribution of fiscal income among tax units. Note: labour income includes income from employment, pensions, as well as other non-business income sources

Top 1 and Top 5–1% income decomposition between business and labour income, 2002–2015.

A robust rise in top business incomes after 2004 was the main reason behind the structural rise in top income shares.Footnote 56 This also calls for a more detailed study of the effect of factor shares (Fig. 18). The period after the EU accession has been associated with capital deepening (Gradzewicz et al., 2014) and rising capital share (Growiec, 2012). With the top 1 percent income group holding almost two-thirds of the total fiscal business income, any notable change in the functional distribution towards capital could result in rising top concentration (e.g. Atkinson, 2009). This observation is confirmed by a regression of income shares on capital share. We construct a panel of four countries (Poland, Germany, Hungary and Czech Republic) for the period between 1995 and 2015, and regress income shares on capital share,Footnote 57 and a set of country fixed effects and year fixed effects. The left side of Fig. 7b reports the estimated non-causal change in income shares, which is attributed to the actual change in capital share between 1995 and 2015. For the sake of brevity, we report only results for Poland and Germany. If the correlations were causal, ceteris paribus, the rise of capital share in Poland would imply the rise of top 1% by 1.4 pp and the fall of all other income groups.

The rise of capital share has often been attributed to the new globalization phase and increasing participation in international trade. We point to three broad channels concerning how globalization might have potentially induced the rising capital share in Poland.Footnote 58 The first channel is the capital-augmenting technological change, which entered Poland through strong foreign direct investment (FDI) after the EU accession (Olszewski, 2009). The second channel is a trade-induced shift towards capital-intensive sectors. Traditional labour-intensive industries, such as mining or textile manufacturing, have been in decline due to the increasing trade competition, especially after China joined the WTO in 2001 (Balsvik et al., 2015; Growiec, 2012). Finally, the rising market power of multinational companies could have also contributed to the falling labour share (Autor et al., 2020; Bell et al., 2018; Benmelech et al., 2018). We provide suggestive evidence for the role of globalisation in the right side of Fig. 7b. We employ a similar method as in the case of capital share, except we regress income shares on the export share of GDP and a full set of country and year fixed effects. The actual rise of export share between 2000 and 2015 predicts (in a non-causal fashion) a strong and statistically significant increase of the top 1% by 4.6 pp, accompanied by a fall of all other income groups.

The distributional effects of globalization and technological change can also explain a decline in the income share of the middle 40% (Fig. 2), which can be attributed to the relative standing of the Polish middle class. It has been documented that middle-skilled jobs in developed economies are more likely to have been automatized, leading to so called ‘job polarization’ (Autor et al., 2006). At the same time, employment in manufacturing—a traditional sector of the middle class—has been in decline due to offshoring and trade competition with developing countries (Autor et al., 2016). The relative fall in the importance of the middle class, which is the ‘back-bone’ of democracy, might be related to the recent rise of populism across the CEE and internationally (Easterly, 2001; Lindner et al., 2020, etc.).

6 International comparison

We next turn to international comparisons. First, we compare the long-run evolution of income inequality in Poland and Western European countries. Figure 9a shows the evolution of the top 1% share in Poland, Germany, France, Sweden and the UK between 1914 and 2014. A broad U-shaped pattern can be observed in all countries throughout the twentieth century, but it has been especially pronounced in Poland. The period between 1914 and 1945 initiated a secular downward inequality trend worldwide due to wars, and political and economic shocks. While WW1 itself was advantageous to top incomes in presented countries, the immediate post-war development hit top incomes hard, with a particularly pronounced decline in Poland. It is now well documented that the evolution of top income shares in developed countries during the first half of the twentieth century reveals the fate of top capital incomes (Atkinson & Piketty, 2007; Atkinson et al., 2011).

Source: Poland: authors' computation based on income tax statistics. Distribution of fiscal income among tax units. Other countries: WID.world. Note: 1914–1919 for Poland refers to the Prussian Poland. b Top 1% in former communist countries, 1890–2015. Source: Poland: authors' computation based on income tax statistics. Distribution of fiscal income among tax units. Other countries: Mavridis & Mosberger, 2017; Novokmet et al. 2018, Novokmet, 2018, WID.world.

a Top 1% in Poland, Germany, France and Sweden, 1914–2014.

While inequality stood at low levels in all countries in the three post-WW2 decades, the introduction of communism dramatically reduced top income shares in Poland and kept them below the levels observed in western European countries. With the fall of communism, the top percentile share substantially increased in Poland between 1989 and 2015, to reach the levels characteristic for more unequal European countries, notably Germany and the UK, and placed Poland significantly above estimates for the group of Continental, Nordic and Southern European countries (e.g. Atkinson et al., 2011). It is interesting to point to the recent similar evolution of the top percentile share in Poland and Germany.Footnote 59