Abstract

Leadership development is essential to the well-being of medical organizations, but leadership concepts do not easily translate into skills or actions. The Mayo Leadership Behavior Index© (Leader Index), a validated instrument describing eight leadership traits associated with constituent well-being, can serve as a guide. The authors analyzed narratives from a qualitative study of senior medical leaders describing successful leadership behaviors to see how the tenets of the Leader Index can be applied. Current/emeritus chairs of major academic departments/divisions from a single institution were asked to describe anecdotes of actions used by leaders in actual settings. Narratives from interviews were analyzed for behaviors that map to the eight traits in the Leader Index. Eleven senior leaders volunteered multiple scenarios of effective and ineffective leadership with illustrative examples. The behaviors they identified mapped to all eight traits of the Leader Index, specifically career conversations, empowerment to do the job, encouragement of ideas, treatment with respect and dignity, provision of job performance feedback and coaching, recognition of well-done work, information about organizational changes, and development of talents and skills. These findings provide faculty development experts and psychologists tangible behaviors and actions they can teach to enhance leadership skills.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Leadership is essential to the well-being of medical organizations as health care is fundamentally a human enterprise and individuals are heavily influenced by their direct leadership (Montgomery, 2016; Smith, 2015; Tawfik et al., 2019). The evidence for the relationship between effective leadership and physician satisfaction, engagement, values alignment, and professional fulfillment has been growing (Penwell-Waines et al., 2018; Shanafelt et al., 2015, 2020, 2021a, 2021b). And a recent national study of close to 5500 physicians across 11 organizations demonstrated that individuals who rated their leaders highest on core leadership traits were almost six times more professionally fulfilled, had almost half the degree of burnout, and were 66% less interested in leaving their current position (Mete et al., 2022). Leadership development is an excellent way to address work force well-being, but it is not without its challenges since leadership concepts and traits do not easily translate into skills or actions (Lucas et al., 2018). Individuals with a track record for teaching leadership skills, such as psychologists (Kirch & Ast, 2017; Robiner et al., 2021; Shaeffer et al., 2020), and individuals who work in faculty development (Jagsi & Spector, 2020; Steinart et al., 2012) can play a unique role.

There are many competing skills that need to be covered in leadership development programs (Tung et al., 2021) and curricular focus can be difficult. One potential guide is the Mayo Leadership Behavior Index© (Leader Index), an instrument developed by Shanafelt and Swensen (Shanafelt et al., 2015) that strongly correlates with the well-being of health care workers, consisting of eight core leadership traits. These traits can serve as a framework for leadership developers to further elaborate upon with teachable, specific leadership behaviors.

Actual leadership scenarios is one method of demonstrating how principles can be turned into actions. We developed a set of narratives from volunteered scenarios of firsthand experiences of senior medical leaders at one of our affiliated institutions, Hospital for Special Surgery. These recounts of actual leadership challenges were collected to address a desire at this institution for a practical leadership ‘roadmap,’ served as springboards for group mentoring discussions, and were not informed by knowledge of the Leader Index.

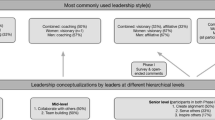

The goals of this report (Fig. 1) were to demonstrate that behaviors and actions identified in the narratives mapped to the eight Leader Index traits, validating this instrument as a theoretical framework for faculty development programs to use in teaching the leadership skills that positively impact constituent well-being.

Methods

Senior leaders at Hospital for Special Surgery (HSS) were recruited as part of a qualitative study to optimize academic mentoring. The protocol was approved by the institutional review board at HSS (protocol 2020-2138) and all participants provided verbal consent. HSS is affiliated with Weill Cornell medicine and is an academic center focusing on musculoskeletal health with faculty in diverse specialties including orthopedic surgery, rheumatology, anesthesiology, physiatry, and radiology/imaging. Current and emeritus chairpersons/chiefs of major departments/divisions were interviewed one-on-one with open-ended questions. Thirteen leaders were recruited, eleven were available and interviewed between March 8, 2021, and April 6, 2021. Interviews emphasized what individuals should do, i.e., what behaviors were necessary to be successful leaders. Participants were asked to relay anecdotes of effective and ineffective leadership, the actions that characterized them, and what potentially jeopardizes success as a leader. The investigator (CAM) recorded responses in field notes, transcribed them into narratives, and coded them to identify unique concepts (described in detail in a prior publication) (Mancuso & Robbins, 2023). For the current report, the investigator re-analyzed the narratives for examples of behaviors that map to the items in the Leader Index (Fig. 1). A second investigator (JT) reviewed the examples to confirm agreement on mapping.

The Leader Index was developed as part of a large institution program to periodically survey physicians and scientists about multiple practices and work-related conditions (Shanafelt et al., 2015). Items for the Leader Index were designed to reflect measurable and actionable characteristics that potentially could be improved upon (Shanafelt et al., 2021a). The Index was validated by showing that more favorable ratings correlated with greater well-being, less work burnout, more job satisfaction (Dyrbye et al., 2020) and also influenced values alignment between individuals and organizations (Shanafelt et al., 2021b). The eight core items address leaders’ interactions with constituents regarding career conversations, empowerment to do the job, encouragement of ideas, treatment with respect and dignity, provision of job performance feedback and coaching, recognition of well-done work, information about organizational changes, and development of talents and skills.

Results

The age range of the eleven leaders was 52–81 years. Four participants were women (mean age 71 year) and seven were men (mean age 64 years). All participants were forthcoming with advice on leadership behaviors by describing their own experiences and the observed experiences of peers. Their responses addressed leadership situations when dealing with senior colleagues, hospital administrators, policy makers, and the individual constituents directly under their leadership (Mancuso & Robbins, 2023). This last category corresponds to the focus of the Leader Index. Participants volunteered multiple anecdotes that mapped to all eight core traits of the Leader Index. The traits are listed below with direct quotations from participants and the number of participants voicing each trait.

Hold Career Conversations (6 Participants)

Senior leaders advised explicit and direct conversations with their faculty about career goals, work activities, and desired future plans and roles.

Ask them what their goals are, then set expectations for their work and plans.

Such conversations were advocated for all faculty, including those not traditionally thought to require mentoring.

Even for the most senior members, ask “how long do you want to do this? how do you see your role for the service and what part of the service do you want to play a role in?”

Empower Constituents to Do the Job (6 Participants)

Senior leaders described a variety of ways to empower their faculty including decoding expected routines (“Help them understand how the system works, the nuances of the place”) and sponsoring new opportunities (“Open doors for them, ensure their membership in networks”). Leaders also provided details on how to effectively delegate, especially by providing structure and being specific with tasks.

If you delegate to others, you must give instructions—for example, be at every teaching conference, you are responsible for ACGME, you are responsible for reviewing the first list of fellowship applicants. Don’t say ‘just run it; just go run the fellowship.’ It is a mistake not to be concrete when you delegate work and responsibility.

They also noted that when leaders delegate, they must choose those who have earned the position and then imbue them with the authority to carry out the job.

It can turn out to be too big for one person. So, divide and delegate more to others. But don’t give without choosing based on merit; educate yourself on who deserves it. Then let them know they are empowered to do it. But make sure you also impart structure, that they know what they are responsible for and that they will have the authority.

Encourage Constituents to Suggest Ideas for Improvement (7 Participants)

Senior leaders advised that good listening skills require humility and openness to different viewpoints (“Be open to listening. Never say ‘that’s not the way I do it.’ Throw out ideas that someone can pick up on. Be ready to say ‘I never thought of that’ [and] “Be attentive to the smaller groups and their goals. Help to preserve their voice, include them in your long-term plans.”).

Leaders offered several methods to achieve this, such as tossing out ideas to the entire group to solicit a variety of reactions as well as meeting privately with individuals and senior advisory groups to vet particular decisions.

Bad leadership is when the leader makes decisions without input from faculty. They are not incorporated into developing and implementing decisions. For example… I [once] made a unilateral decision about funding… it was not well received… The solution to this scenario was to collect individuals and set up a committee …to discuss options, vet opinions. There should have been a senior advisory group with some chiefs to pound it out, then get them to refine the decision.

If you have a new plan or initiative that you will present to a group, first meet with individuals privately, get them to buy in along the way. Otherwise, you won’t know how they might feel about it. Get their input. Have the support of others who are not afraid to speak up.

Treat Constituents with Respect and Dignity (10 Participants)

Conveying respect and ensuring dignity can take many forms and are not always intuitive (“Don’t assume your people are like you are, instead you need to adapt to your group” [and] “…make them feel that you heard them and support them in important issues. Acknowledge their issues.”) Seasoned leaders emphasized that it is important to establish baseline credibility, walking the walk alongside their constituents (“You can only be empathetic if you are experiencing what they are doing. Be in the trenches, join where they are. Do the job, show you are experiencing what they are at that time.” [and] “Go to their workplace, whether office or lab. You need to show appreciation, that you respect and value them.”).

Leaders noted that certain situations are particularly challenging, e.g., when emotions are high or when subordinates show disrespect.

Approach people in a non-adversarial way when you have a highly hot topic, even if controversial and at odds with others. Be dispassionate; as soon as you are in fighting mode, you are not leading any more. Think and communicate. There is no winning or losing, only best compromises.

Another important thing to remember is not to over-react. You may ask “where did that come from?” It is hard for a leader to figure out why they said or did something, but don’t ruminate on it. Move on instead. Continue to have a relationship with that person. Don’t dwell on it, don’t hate for life.

Another challenge is how leaders should deal with their mistakes, so their constituents do not have to function under bad decisions.

Not all decisions are perfect or correct, you never have 100% of the information… if you are wrong, explain it and correct it. Don’t ignore people who notice and voice that they notice. Address that you made a mistake.

If you make a bad decision, admit it, be transparent. If a program is a mistake, rectify it or disband it. Do not throw subordinates under the bus by blaming them or making them have to live with a mistake.

Provide Performance Feedback and Coaching (4 Participants)

Senior leaders advised private feedback (“Honest thoughts should be expressed only one-on-one”) and should “focus on shared values.” Also “If something is not right and you have to give feedback, do so without taking over and micro-managing.” Leaders also advised that coaching entails lauding current job performance as well as striving for higher goals “If you are mentoring a leader, a challenge is to get the mentee to pick an area of inquiry where not all the answers are known.”

Recognize a Job Well Done (5 Participants)

Senior leaders advocated acknowledging good work by “giving rewards that matter to them”; examples offered were “issue protected time, authorship, a fellow promotion based on merit.” In addition, “Obtain more resources for them to pursue their interests and improve their workplace; try to raise money for your people.” Senior leaders also acknowledged that successes often result from team effort, and in these situations, leaders should step away from the limelight to ensure their constituents receive most of the credit.

A good leader will take an idea and make others feel it was their idea. A good leader doesn’t care for credit. Selflessness is what is important. A good leader brings out the best in others, gets out of the way, lets others take the glory.

You really need an element of generosity. You must get out of one’s desires and think what does the division need, and want to make this better. You must relinquish some opportunities to advance yourself.

Provide Information About Organizational Change (5 Participants)

Leaders noted that frequent communication is needed to apprise constitutes of organizational changes and how decisions are made (“Be transparent and fair with decisions; communicate why you are doing something.” [and] “Provide Q&A; tell them how challenges were met.”) Leaders acknowledged that communication is also important to secure cooperation.

It is not good to say ‘here is the end result of a priority, now you make it work.’ An example is [a recent partnership]. The direct input of physicians was not taken into account, there was a domino effect of problems with lack of buy in and loss of trust. It could have been avoided.

Senior leaders also emphasized that communication is needed multiple times and across different platforms.

Tell everyone about your future goals, keep looking forward. Then communicate and over communicate. You cannot over communicate enough. Most don’t hear it the first, second or third time, but hear it the fourth or fifth time.

For me I hear something and remember it forever. I initially assumed everyone was like that too. I would announce it at a meeting or in an email and then wonder why are they ignoring this? Now I over communicate and in multiple medias.

Encourage Development of Constituent’s Talents and Skills (9 Participants)

Leaders reported that “It is important to recognize strengths and weaknesses of each subordinate and choose ways for each to be effective.” Then the leader needs to “support that person’s strengths” [and] “always look for ways to promote constituents, for opportunities to help them achieve their potential.”

Sometimes this requires proactively seeking opportunities for constituents outside the typical offerings at the institution.

A person needs the tools. I got an MBA to focus on leadership. Formal education is key to getting tools and teaching. We need tools to be effective. On-the-job training is one way to get it, but it is difficult to do it that way. In addition to on-the-job training, you need formal training.

Leaders also noted it is bad leadership to suppress advancement of constituents because of perceived threat and the desire for personal gain.

There was leader who although he had a good reputation and appeared confident, he actually was insecure, and he would block subordinates because he didn’t like them personally or felt threatened by their very ambitious motivation. He worked to hold them down, not put them in the mix. He disincentivized people, he put in his cronies, had yes men around him and a lot of people on the service became very discouraged; it was very discouraging to the rest of the group.

According to the senior leaders, look for skills and talents the leader may not have (“The most important thing leaders must care more about those they are leading, as much as or more than themselves. Hire those who are smarter and better than you are and let them run their group.”).

Discussion

This report summarizes actual leadership scenarios volunteered by established senior leaders that mapped to all eight traits in the Leader Index. Multiple examples provided by most of the leaders throughout their interviews support the validity of using the Leader Index as a theoretical framework for medical leadership curricula that aims to impact constituent engagement and well-being. In addition, applying a framework developed by others in different medical systems provides credibility and standardization for curriculum development and its potential dissemination to other academic settings.

There were specific behaviors corresponding to the framework that were described by the senior leaders that can be used in instructional environments. They specified that career conversations with constituents should include explicit goals, detailed roles, and realistic timelines. They described job empowerment to include explanations of institutional systems, right sizing of tasks, and provision of structure along with new authority to delegate. To encourage employees to suggest ideas for improvement, they suggested a variety of methods for conducting meetings, including roundtable solicitation of ideas or straw man suggestions to stimulate discourse. While everyone would likely agree that treating employees with respect and dignity is vitally important, conveying respect is not always intuitive, especially when tensions may be high. These leaders stressed the importance of remaining calm during conflict and owning mistakes when inadvertently made. Feedback, they advised, should be delivered privately, and coaching done without micromanagement. Credit and meaningful rewards should be bestowed generously and often. Repetition is necessary for well-delivered communication and the rationale for decisions, those executed and not executed, should always be given. Finally, health professionals need to feel that they are constantly growing, and their skills need to be supported though professional development opportunities. This set of recommendations, while applicable and useful for many medical organizations, is especially helpful for institutions such as Hospital for Special Surgery, where leaders from surgical specialties are often revered for their technical prowess, rising in position without enough opportunity to focus specifically on their leadership skills (Palmer et al., 2015). This setting was the impetus for assembling practical, hands-on advice, and a roadmap of actionable leadership.

As desired next steps, our findings suggest potential behavioral enhancements to complement instruction on attitudinal and interpersonal skills. For example, possible topics on how to treat people with respect and dignity can include a practice of acting dispassionately under high emotion or learning how to get comfortable with owning errors. Designing instructional methods for managing such situations could include case studies, role playing, identifying pros/cons of responses to actual leadership dilemmas, and directly observed practice with real-time feedback.

A multi-disciplinary team of faculty development experts and psychologists are optimal to lead in the hands-on teaching of these behaviors and skills. For example, in implementing fundamental tenets of the Leader Index, psychologists can guide learners in interpretations and deductions from everyday challenges. Their expertise in teaching well-developed interpersonal skills between leaders and their constituents and in emphasizing the link between constituent well-being and fruitful interactions with institutional leaders is invaluable.

In conclusion, our findings add to the body of knowledge that medical leadership has attitudinal and relational components that can be taught as actionable behaviors within an established theoretical framework. Advancing skills in leadership that can impact constituent well-being will require an enhanced curriculum that is developed and delivered by a multi-disciplinary team of psychologists and educators devoted to professional faculty development.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are not openly available due to reasons of sensitivity and are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are located in controlled access storage at Hospital for Special Surgery.

References

Dyrbye, N., Major, E. B., Hays, T., Fraser, H., Buskirk, J., & West, P. (2020). Relationship between organizational leadership and health care employee burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 295, 698–708.

Jagsi, R., & Spector, N. (2020). Leading by design: Lessons for the future from 25 years of the Executive Leadership in Academic Medicine (ELAM) program for women. Academic Medicine, 95, 1479–1482.

Kirch, D., & Ast, C. (2017). Health care transformation: The role of academic health center and their psychologists. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 24, 86–91.

Lucas, R., Goldman, E., Scott, A., & Dander, V. (2018). Leadership development programs at academic health centers: Results from a national survey. Academic Medicine, 93, 229–236.

Mancuso, C., & Robbins, L. (2023). Narratives of actionable medical leadership from senior leaders for aspiring leaders in academic medicine. Hospital for Special Surgery Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/15563316231179472

Mete, M., Goldman, C., Shanafelt, T., & Marchalik, D. (2022). Impact of leadership behavior on physician well-being, burnout, professional fulfilment and intention to leave: A multicentre cross-sectional survey study. British Medical Journal Open, 12, 1–7.

Montgomery, A. (2016). The relationship between leadership and physician well-being: A scoping review. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 8, 71–80.

Palmer, M., Hoffmann-Longtin, K., Walvoord, E., Bogdewic, S., & Dankoski, M. (2015). A competency-based approach to recruiting, developing, and giving feedback to department chairs. Academic Medicine, 90, 425–430.

Penwell-Waines, L., Ward, W., Kirkpatrick, H., Smith, P., & Abouljoud, M. (2018). Perspectives on health care provider well-being: Looking back, moving forward. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 25, 295–304.

Robiner, W., Hong, B., & Ward, W. (2021). Psychologist’s contributions to medical education and interprofessional education in medical schools. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 26, 666–678.

Shaffer, L. A., Robiner, W., Cash, L., Hong, B., Washburn, J. J., & Ward, W. (2020). Psychologist leadership roles and leadership training needs in academic health centers. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 28, 252–261.

Shanafelt, T., Gorringe, G., Menaker, R., Storz, K., Reeves, D., Buskirk, S., Sloan, J., & Swenson, S. (2015). Impact of organizational leadership on physician burnout and satisfaction. Mayo Clinic Proceedings, 90, 432–440.

Shanafelt, T., Makowski, M., Wang, H., Bohman, B., Leonard, M., Harrington, R., Minor, L., & Trocket, M. (2020). Association of burnout, professional fulfillment and self-care practices of physician leaders with their independently rated leadership effectiveness. JAMA Network Open, 3, 1–11.

Shanafelt, T., Trockel, M., Rodriguez, A., & Logan, D. (2021a). Wellness-centered leadership: Equipping health care leaders to cultivate physician well-being and professional fulfillment. Academic Medicine, 96, 641–651.

Shanafelt, T., Wang, H., Leonard, M., Hawn, M., McKenna, Q., Majzun, R., Minor, L., & Trockel, M. (2021b). Assessment of the association of leadership behaviors of supervising physicians with personal-organizational values alignment among staff physician. JAMA Network Open, 4, 1–12.

Smith, P. (2015). Leadership in academic health centers: Transactional and transformational leadership. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 22, 228–231.

Steinart, Y., Naismith, L., & Mann, K. (2012). Faculty development initiatives designed to promote leadership in medical education. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 19. Medical Teacher, 24, 483–503.

Tawfik, D., Profit, J., Webber, S., & Shanafelt, T. (2019). Organizational factors affecting physician well-being. Current Treatment Options in Pediatrics, 5, 11–25.

Tung, J., Nahid, M., Rajan, M., & Logio, L. (2021). The impact of a faculty development program, the Leadership in Academic Medicine Program (LAMP), on self-efficacy, academic promotion, and institutional retention. BMC Medical Education, 21, 1–9.

Funding

The study was supported by Hospital for Special Surgery and the Office of Faculty Development, Weill Cornell Medicine.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design and to drafting or reviewing the work critically for intellectual content. JT and CAM conceived and designed the study, acquired, and interpreted the data, drafted and wrote the manuscript. MN and MR and SB contributed to the intellectual content, interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Judy Tung, Musarrat Nahid, Mangala Rajan, Stephen Bogdewic, Carol A. Mancuso have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval

This study was first approved by the Institutional Review Board at Hospital for Special Surgery (protocol 2020–2138) in 2020 and renewed in 2022.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tung, J., Nahid, M., Rajan, M. et al. Putting Traits Associated with Effective Medical Leadership into Action: Support for a Faculty Development Strategy. J Clin Psychol Med Settings (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-024-10031-7

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-024-10031-7