Abstract

The study aims to empirically assess the control-mastery theory hypothesis that considers chronic couple conflictuality as the repetition of relational vicious circles—that is, interactions where both partners test their pathogenic beliefs and fail their reciprocal tests, confirming their reciprocal pathogenic beliefs. In addition, the study aims to verify if interpersonal guilt is more activated during couple conflicts. Our study involved 11 couples treated by four experienced therapists and nine trained, independent judges who, after reading verbatim transcripts of the couples’ psychotherapy sessions, used the Patient Scale of Couple Testing (PSCT), and the Patient Interpersonal Guilt Rating Scale (PIGRS) to rate segments of couple sessions. The results were obtained by applying generalized estimating equations and confirm our hypotheses: we could observe a greater presence of testing activity and confirmation of pathogenic beliefs in segments classified as conflictual for both partners and a stronger presence of interpersonal guilt in conflictual versus nonconflictual interactions. These findings support the idea that conflict interactions can be seen as failed attempts by both partners to disconfirm their pathogenic beliefs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Within the psychoanalytic and systemic traditions, dysfunctional couple conflicts have been mainly understood as the consequences of three broad factors: (1) the excessive use of projective identification (Nielsen, 2019), (2) the presence of deficits in the abilities of mentalization and affective regulation (Feeney & Fitzgerald, 2019), and (3) the collapse of effective communication strategies (Ringstrom, 2012). Moreover, research (Crenshaw et al., 2021) has highlighted the importance of specific topics that trigger couple conflict, suggesting that dysfunctional interactions can be the outcome of communication deficits and stressing the influence of gender roles on demand/withdrawn conflict configurations.

Notwithstanding the theoretical and clinical importance of the topic of chronic couple conflictuality, there have been no empirical studies analyzing chronic conflictuality from the perspective of control-mastery theory (CMT), which is an integrative, cognitive-dynamic relational theory of psychic functioning, psychopathology, and the psychotherapy process. CMT was originally developed by Joseph Weiss and empirically validated by the San Francisco Psychotherapy Research Group and the Control-Mastery Theory–Italian Group (Gazzillo et al., 2021; Gazzillo, 2023; Silberschatz, 2005; Weiss, 1993; Weiss et al., 1986). According to CMT, human beings (consciously and unconsciously) exert some degree of control over their mental processes by following a safety principle (Fiorenza et al., 2023) and are intrinsically motivated to adapt to reality, master traumas, and solve problems. To adapt to reality, since infancy they have learned to develop a system of beliefs (conscious/unconscious, explicit/implicit) about reality and morality that will guide them throughout adulthood. According to CMT, psychopathology stems from the unconscious pathogenic beliefs developed to adapt to childhood traumatic and adverse experiences (Fimiani et al., 2020). These beliefs are considered pathogenic because they associate the pursuit of healthy and adaptive goals with harm to the self, to significant others, or to important relationships, and arouse fear, shame, or guilt (Bush, 2005; Faccini et al., 2020; Gazzillo, 2022). Many of these pathogenic beliefs result in maladaptive interpersonal guilt.

CMT has deepened the understanding of five broad families of pathogenic beliefs that fuel interpersonal guilt: (1) survivor’s guilt, which is based on the belief that having more success, capacity, wealth, and so forth than loved ones makes them suffer; (2) separation/disloyalty guilt, which is based on the belief that separating, differentiating, and becoming autonomous from loved ones will hurt them; (3) omnipotent responsibility guilt, which stems from the belief that one has the duty and power to make other people feel happy and must take care of loved ones in distress, putting aside any personal need; (4) self-hate, which involves the feeling that one is inherently wrong, inept, and bad and, thus, undeserving of love and respect from others; and (5) burdening guilt, which is derived from the belief that one’s own needs are unduly burdensome to others.

Because these beliefs are constricting and painful, people are often unconsciously powerfully motivated to disconfirm them, testing them in their close relationships (even therapeutic ones). Tests involve communication, attitudes, and behaviors (unconsciously) aimed at disproving pathogenic beliefs. By testing, people actively seek—albeit unconsciously—experiences that will help them master the traumas underlying those beliefs (Fimiani et al., 2022). Usually, a patient tests his/her therapist by expressing or stirring up emotions that are stronger than usual (Gazzillo et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c; Gazzillo et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c); making an implicit or explicit request; behaving more absurdly, illogically, or provocatively than usual; or placing the therapist in a situation where they feel pressure to intervene in some way (Weiss, 1993). When the therapist passes the patient’s tests, through communication, attitudes, or interventions that are experienced by the patient as disconfirming the pathogenic belief, the latter will likely become less anxious and depressed and more involved in the therapeutic work and relationship, gain new insights, and show other signs of improvement.

According to the CMT, there are two main testing strategies: transference testing and passive-into-active testing. Someone conducting a transference test may behave as though the pathogenic belief that they want to disprove is true (transference test by compliance) or behave in a way that defies it (transference test by noncompliance). The hope is that the other person will respond differently from traumatizing parents/others when the individual tries to pursue adaptive goals that they fear will cause danger or harm. In passive-into-active testing, the person puts the other in a position similar to the one they previously held in a traumatizing situation or relationship. The person may identify with a traumatizing caregiver and treat another person in a way that they previously experienced as traumatizing (passive-into-active test by compliance). Conversely, the person may treat the other the way they would have wanted to be treated (passive-into-active test by noncompliance), hoping that this person will appreciate that behavior and, thus, legitimize their thwarted infantile needs. Thus, by observing the other’s response to both kinds of passive-into-active testing, the person can begin to disprove pathogenic beliefs (Gazzillo et al., 2019; Gazzillo et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c).

By virtue of the adaptive unconscious motivation and abilities of patients to get better through therapy, patients usually come into psychotherapy with a more or less conscious plan to achieve their healthy goals, disconfirm their pathogenic beliefs (mainly through testing activity), and master their traumas (Gazzillo et al., 2019). This plan underlines the general areas the patient wants to work on and the patient’s likely approach for undertaking this work, and it can be useful for the therapist to deliver a case-specific treatment (Gazzillo et al., 2022a, 2022b, 2022c), that is, a therapy set up and conducted based on the specific goals, pathogenic beliefs, traumas, and testing strategies of a patient. The therapist’s task is to support the patient’s plan by providing pro-plan responses.

The Plan Formulation Method (PFM) is an empirically validated, standardized procedure that has been developed and validated to formulate the patient’s plan (Curtis & Silberschatz, 2022). It has five components: (1) healthy and adaptive goals, (2) the pathogenic beliefs obstructing the achievement of these goals, (3) the traumas that contributed to the development of the pathogenic beliefs, (4) the ways in which the pathogenic beliefs might be tested within the therapy (tests), and (5) the kind of understanding (insights) or experiences that may be helpful for the patient to gain.

Couples Therapy and Chronic Conflictuality in Control-Mastery Theory

CMT has also been applied in settings with couples (Zeitlin, 1991). In line with other approaches to couples therapy (Elkaïm, 1997; Epstein & Zheng, 2017; Lebow, 2019; Sprenkle et al., 2009), the hypothesis is that a circular causality exists between the beliefs, emotional experiences, attitudes, and behaviors of the individual partners and overall organization of the couple system. Intimate relationships, in fact, by virtue of their emotional stability and intimate involvement, represent a privileged field for partners to test their pathogenic beliefs, and when one partner fails the tests, the other partner can retest them, which encourages even more testing activity in the couple.

Couples request therapy for different reasons; a cross-cutting element is chronic conflictuality and the suffering that arises from what CMT defines as relational vicious circles (Fiorenza et al., submitted for publication; Rodomonti et al., 2019, 2022). Relational vicious circles are rigid and repetitive maladaptive patterns derived from the failure of partners to pass their reciprocal tests, thus confirming their pathogenic beliefs, increasing individual and couple suffering and conflicts, and decreasing dyadic satisfaction. According to this perspective, partners experience a chronic and distressing conflict when they systematically fail their reciprocal tests, thus confirming their individual pathogenic beliefs. Suppose Partner 1 has the pathogenic belief that her own needs burden others (burdening). Partner 1 tests this belief in transference by noncompliance, beginning to complain to Partner 2 while he is relaxing after a busy day. Partner 2 has the pathogenic belief that he has a duty to take care of others by giving up his own needs (omnipotence responsibility). In an attempt, then, to rebel against this belief, he does not show interest in Partner 1 (transference test by noncompliance), rather showing himself burdened by her problems. Partner 2’s attitude of apparent disinterest could be read by Partner 1 as a confirmation of her own pathogenic belief related to burdening. To disconfirm it, Partner 1 will continue to test it by noncompliance by showing she is in pain and becoming very demanding. This will then confirm Partner 2’s belief that he must take care of loved people to make them happy; thus, Partner 1 fails his test. As a result, Partner 2 will test his belief more vigorously, acting even more dismissively and showing progressively more lack of attention, again confirming Partner 1’s pathogenic belief and perpetuating the vicious relational cycle.

However, according to CMT, in intimate relationships, there also exists a functional class of circular dynamics, called virtuous relational circles (Fiorenza et al., submitted for publication; Rodomonti et al., 2019, 2022), that represent resources that allow the partners to disconfirm their pathogenic beliefs and provide a more positive relationship model. In other words, these dynamics can be understood as the reasons why partners feel safe and want to be together. For example, Partner 3 developed the pathogenic belief that being more successful than loved ones would humiliate them (survivor). Suppose he gets a promotion at work; Partner 4, who has the pathogenic belief that she does not deserve love and attention from the other (self-hate), welcomes him by celebrating and praising him for his success (passive-into-active test by non-compliance). This disconfirms Partner 3’s pathogenic belief supporting survivor guilt. Partner 3, then, feeling supported, tells her that being with her has given him the strength to commit himself, so he decides to invite Partner 4 to her favorite restaurant for dinner to celebrate, making her feel valuable and disconfirming the pathogenic belief supporting self-hate.

Because CMT can also be applied to couple dynamics, the plan formulation method for couples (PFMC; Rodomonti et al., 2022) was developed and empirically validated as an adaptation of the PFM to the specificities of couples therapy; it consists of six sections: (1) the couple’s goal; (2) the obstructions—that is, pathogenic beliefs that prevent the couple’s achievement of adaptive goals (divided into the individual and shared pathogenic beliefs); (3) traumas, which are all those experiences that led to the formation of pathogenic beliefs (divided into individual couple traumas); (4) relational vicious circles; (5) relational virtuous circles; and (6) relational insights that may help the couple understand the origin and significance of their pathogenic beliefs, traumas, and vicious relational circles.

Within the therapeutic setting, the goal is to make the partners aware of the meanings, activating factors and the origins of their vicious circles, helping them reinforce virtuous circles with the aims of supporting their ability to pass each other’s tests, disconfirming each other’s pathogenic beliefs, and creating a climate of emotional stability and safety in the relationship. As with individual therapies, it is also important for the therapist to pass the tests that the couple gives them.

Aims and Hypotheses

The main aim of the present study is to empirically assess the hypothesis that the repetition of relational vicious circles—that is, interactions in which both partners test each other and fail their reciprocal tests—is an essential component of chronic couple conflictuality. The second aim is to observe, through the Patients’ Interpersonal Guilt Rating Scale (PIGRS), the interpersonal guilt activated during couple conflicts because guilt is derived from and sustains many of the pathogenic beliefs that trigger vicious relational circles and conflicts within a relationship. In particular, in a conflictual interaction, we expect the activation of self-hate. Several research studies (Kealy et al., 2021; Fimiani et al., 2020; Leonardi et al., 2020, 2022) have shown that self-hate is associated with the development of severe discomfort and disorders. It is reasonable to hypothesize that, within an intimate relationship, self-hate may contribute to vicious relational circles where one or both partners feel unworthy of love and respect and do not expect understanding and empathy for their suffering from the other partner. We believe that attempts at unconscious self-punishment due to guilt are, along with failure to disconfirm pathogenic beliefs, two of the most important sources of couple conflict.

In sum, we hypothesize that higher levels of testing failure will be present in segments classified as conflictual compared with those classified as nonconflictual. We also hypothesize that a systematic relationship will exist between couple conflictuality and the presence of guilt, particularly self-hate.

Methods

Participants

The sample is the same as the one used to empirically validate the PFMC (see Rodomonti et al., 2022) and consists of verbatim transcripts of the first two sessions of psychotherapy for 15 couples who required couples therapy in both public and private settings. We decided to assess the first two sessions of couple therapy based on the hypothesis that, in these first sessions, the couples’ interactions, not having been significantly modified by the therapy, would have been as similar as possible to the interactions the partners have at home. As inclusion criteria, couples had to live together—although they did not necessarily have to be married—and had to have been in a stable relationship for at least two years. We selected couples based on their complaints about relationship problems and general lack of satisfaction with their intimate relationship. Exclusion criteria were evidence of psychosis, severe substance abuse, or organic brain impairment in one or both partners. The average age of the participants was 50.67 years for men (SD = 8.05; range of 39–70 years) and 46.87 years for women (SD = 10.40; range of 31–72 years). All couples were heterosexual, were Italian, and had children; the self-reported social-financial status of two couples was low; in eight couples, it was medium; and in five couples, it was high. Of the 30 partners, only 10 had previous experience with individual psychotherapy. However, only 11 couples were analyzed because the others did not achieve a good inter-rater reliability score regarding the identification of conflictual versus nonconflictual segments; hence, they were excluded from the research.

Measures

The Plan Formulation Method for Couples (PFMC; Rodomonti et al., 2022) is an empirically validated procedure for formulating the case, planning, and monitoring couple therapies according to CMT, here following the five steps indicated by Curtis et al. (1994) for the formulation of the plan for adult patients. Rodomonti et al. (2022) used it to formulate couples’ plans. The results of this study showed good interjudge reliability for each couple’s plan formulation (average ICC = 0.82), attesting to the validity of the procedure.

For the identification of conflictual versus nonconflictual segments, the raters rated a sample of 248 transcribed session segments (see below) on a 5-point Likert scale created ad hoc from 0 (the segment is nonconflictual) to 4 (the segment is entirely conflictual). Only segments with an average score ≥ 3 were considered relevant. For this reason, from a total of 248, only 92 segments were used in the research.

The Patient Scale of Couple Testing (PSCT; Gazzillo & Fiorenza, 2021b) is a revised version of the Patient Scale of Key Test (see Silberschatz & Curtis, 1986) and is rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (partner is not testing/partner is not confirming partner’s pathogenic beliefs) to 4 (partner is testing/partner is confirming partner’s pathogenic beliefs). It also assesses the degree to which each of the previously selected segments represents a clear example of a test—that is, an instance of one partner testing a pathogenic belief in the relationship.

The Patient Interpersonal Guilt Rating Scale (PIGRS; Gazzillo & Fiorenza, 2021a) is a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no presence of interpersonal guilt) to 4 (clear presence of interpersonal guilt). It is an ad hoc adaptation for assessing the presence and intensity of interpersonal guilt within segments of psychotherapy sessions of the Interpersonal Guilt Rating Scale-15 clinician report (IGRS15-c; Gazzillo et al., 2017), which is a brief clinician-rated tool for clinically assessing interpersonal guilt as conceived in CMT.

Raters

The current study involved nine independent judges who assessed the transcriptions using the scales described in the previous section. The judges were divided into four groups and assigned to different scales. All the judges are female, and their average age was 32 years (SD = 5.25; range of 26–41 years). Three judges had a PhD in dynamic and clinical psychology and had completed training in psychodynamic and/or systemic psychotherapy with three or more years of post-training clinical experience, three had a master’s degree in clinical psychology and a specialization in clinical and/or psychodynamic psychotherapy with three or more years of post-training clinical experience, and three had a master’s degree in clinical psychology and were completing their training in psychodynamic psychotherapy. All judges completed a 98-h course on the theoretical basis and clinical application of CMT provided by the CMT-IG before participating in the present study. This course included 80 h of training in the PFM and its application in clinical practice.

Procedures

Using the couples’ plans that had already been formulated in our research group’s previous study (Rodomonti et al., 2022), the procedure was as follows: (1) One judge read the transcripts and extrapolated an equal number of segments in which the couple presumably interacted conflictually and nonconflictually; these segments were subsequently randomized and read by two independent judges, identifying all possible circumstances in which the couple enacted conflictual and nonconflictual interactions. (2) Passages of the same length identified as conflictual and nonconflictual were extrapolated from the transcriptions. Three other independent raters read the passages and rated the presence of testing using the Patient Scale of Key Test and how much the partner passed the tests. (3) Three other raters rated the presence of the five forms of interpersonal guilt on the Patient Scale of Couple Testing. In each step, the raters read the segments without knowing which category the segments belonged to and used the couples’ plan for evaluations.

Statistical Analysis

A series of descriptive statistics was estimated for all variables included in the study (i.e., mean and standard deviation). To compare the intensity and passing of testing activity in conflictual versus nonconflictual interactions and the intensity of guilt present in these two categories of interactions, generalized estimating equations (GEEs; Ziegler & Vens, 2010) were applied. Using GEEs allowed us to control for pair-specific variance (within subjects) in conflictual and nonconflictual interactions in the same couple therapy. All analyses were performed using SPSS.26.

Results

Tables 1, 2, and 3 present the descriptive statistics for all included variables. The means and standard deviation of the level of conflictuality of conflictual segments and nonconflictual segments were, respectively, M = 1.52, SD = 1.02 and M = 0.99, SD = 0.85.Footnote 1

Regarding the identification of conflictual versus nonconflictual segments, the average pooled ICC of the identification of conflictual versus nonconflictual segments assessed by two independent judges was 0.72.

We also obtained good levels of inter-rater reliability for the ratings of couples’ tests; the pooled ICC of the PSCT assessed by three independent judges on 92 segments of partners’ communication was 0.80 for the intensity of partners’ testing activity and 0.85 for the partners’ confirmation pathogenic beliefs.

We obtained adequate levels of interjudge reliability for the ratings of interpersonal guilt; the pooled ICC of the PIGRS assessed by three independent judges on 92 segments of patients’ communication was 0.67, ranging from 0.26 to 0.86. Specifically, survivor guilt assessed in the female partner and burdening guilt in the male partner had inter-rater reliability scores below 0.70; therefore, they were not included in the data analysis.

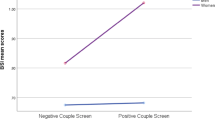

To investigate the first hypothesis, we ran GEEs to compare the presence and intensity of testing activity and of test failing in conflictual versus nonconflictual interactions. The results show a greater presence of testing activity and confirmation of pathogenic beliefs in segments classified as conflictual for both partners (Table 3). We found no differences in the intensity of testing or in the failures in passing tests between conflictual and nonconflictual segments. In line with our first hypothesis, the difference between conflictual and nonconflictual interactions was in the presence of the activity of testing pathogenic beliefs in one partner and the failure of the other partner in passing these tests.

To assess the second hypothesis, we ran GEEs to compare the intensity of interpersonal guilt in conflictual versus nonconflictual interactions. Table 4 shows that there was a stronger presence of interpersonal guilt in conflictual versus nonconflictual interactions, except for omnipotent responsibility guilt for female partners. In other words, in conflictual segments, we were able to find higher levels of separation/disloyalty, self-hate, and burdening guilt in female partners and higher levels of survivor, separation/disloyalty, omnipotent responsibility, and self-hate guilt in male partners. Partially in line with our second hypothesis, the difference between conflictual and nonconflictual segments was in the presence of the activation of interpersonal guilt in both partners.

Discussion

The findings support our first hypotheses (Rodomonti et al., 2019), according to which conflictual interactions can be seen as attempts by both partners to disconfirm their pathogenic beliefs and create a sense of safety within the relationship; thus, repeated test failures by each partner cause negative escalations that can lead to an impasse and suffering. In couples therapy sessions, the therapist, through a good formulation of the couple’s plan, had the fundamental task of identifying and interrupting dysfunctional relational circles while helping the partners enhance their ability to reciprocally pass their tests—in other words, increasing virtuous relational circles that help the couple to become a therapeutic field in which the partners can experiment safely through each one’s ability to disconfirm the other’s pathogenic beliefs (Rodomonti et al., 2022). Clarifying these dynamics can enable therapists to defuse negative emotions and foster an alternative view of reality, as well as help the couple experiment with new, more functional relational modes. Indeed, if the therapist—whatever their theoretical approach—supports the couple’s plan, the individual partners and couple improve, and the therapy progresses (Rodomonti et al., 2022).

The second aim of the study was to empirically assess the stronger presence of interpersonal guilt in segments classified as conflictual. The results revealed that interpersonal guilt was the most active in conflict interactions. This finding is in line with the hypothesis within CMT that guilt is derived from and sustains many of the pathogenic beliefs (Gazzillo et al., 2019) that cause vicious relational circles and conflicts within an intimate relationship. Although we assumed greater activation of self-hate during conflictual interactions, the data contradict this. Indeed, our results suggest that all guilt, except for omnipotent responsibility in female partners, concurs with the activation of testing and testing failure, hence sustaining vicious relational circles.

Limitations and Future Directions

One of the limitations of the present research was the rather limited sample (11 couples). Moreover, the couple conflicts that we were able to investigate were confined to those that occurred or recounted within the couple’s therapy. Another limitation was the sex of the raters because the judges were all females. Finally, low inter-rater reliability scores for survivor guilt (she) and burdening guilt (he) prevented us from assessing their contributions to couple conflictuality.

However, because the data confirm that vicious circles, which cause chronic conflict in an intimate relationship, represent the systematic failure of partners to pass their reciprocal tests, we can assume that, in clinical work, if the therapist follows the couple’s plan, identifies the pathogenic beliefs, and passes and help the partners pass their reciprocal tests, this can contribute to the couple’s improvement in therapy; more importantly, it can help the partners learn to pass each other’s tests in daily life as well, reinforcing those virtuous circles that promote couple well-being and satisfaction.

Notes

Analyzing the conflictual segments, the average length of female partners was 528.20 (sd = 367.61), and the average length of male partners was 471.20 (sd = 344.32). Analysis of the difference between the two averages showed T student = .37 p = .71, so there is no significant difference.

References

Bush, M. (2005). The role of unconscious guilt in psychopathology and in psychotherapy. In G. Silberschatz (Ed.), Transformative relationships: The control mastery theory of psychotherapy (pp. 43–66). Routledge.

Crenshaw, A. O., Leo, K., Christensen, A., Hogan, J. N., Baucom, K. J. W., & Baucom, B. R. W. (2021). Relative importance of conflict topics for within-couple tests: The case of demand/withdraw interaction. Journal of Family Psychology, 35(3), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000782

Curtis, J. T., & Silberschatz, G. (2022). The plan formulation method. In T. D. Eells (Ed.), Handbook of psychotherapy case formulation (3rd ed., pp. 88–112). Guilford Press.

Elkaïm, M. (1997). If you love me, don’t love me: Undoing reciprocal double binds and other methods of change in couple and family therapy. Jason Aronson.

Epstein, N. B., & Zheng, L. (2017). Cognitive-behavioral couple therapy. Current Opinion in Psychology, 13, 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.09.004

Faccini, F., Gazzillo, F., Gorman, B. S., De Luca, E., & Dazzi, N. (2020). Guilt, shame, empathy, self-esteem, and traumas: New data for the validation of the interpersonal guilt rating scale–15 self-report (IGRS-15s). Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 48(1), 79–100. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2020.48.1.79

Feeney, J., & Fitzgerald, J. (2019). Attachment, conflict and relationship quality: Laboratory-based and clinical insights. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 127–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.04.002

Fimiani, R., Gazzillo, F., Fiorenza, E., Rodomonti, M., & Silberschatz, G. (2020). Traumas and their consequences according to control-mastery theory. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 48, 113–139. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2020.48.2.113

Fimiani, R., Gazzillo, F., Gorman, B., Leonardi, J., Biuso, G. S., Rodomonti, M., Mannocchi, C., & Genova, F. (2022). The therapeutic effects of the therapists’ ability to pass their patients’ tests in psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2022.2157227

Fiorenza, E., Santodoro, M., Dazzi, N., & Gazzillo, F. (2023). Safety in control-mastery theory. International Forum of Psychoanalysis. https://doi.org/10.1080/0803706X.2023.2168056

Gazzillo, F. (2022). Toward a more comprehensive understanding of pathogenic beliefs: Theory and clinical implications. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 53, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-022-09564-5

Gazzillo, F. (2023). La Control-Mastery Theory nella pratica clinica. Carocci Editore.

Gazzillo, F., Bush, M., & Kealy, D. (2022a). The plan formulation method from control mastery theory and management of countertransference. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 50(4), 639–658. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2022.50.4.639

Gazzillo, F., Curtis, J., & Silberschatz, G. (2022b). The plan formulation method: An empirically validated and clinically useful procedure applied to a clinical case of a patient with a severe personality disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(3), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23299

Gazzillo, F., Dimaggio, G., & Curtis, J. T. (2021). Case formulation and treatment planning: How to take care of relationship and symptoms together. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 31(2), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/int0000185

Gazzillo, F., & Fiorenza, E. (2021a). Patient Interpersonal Guilt Rating Scale (PIGRS) [Unpublished manuscript]. Sapienza University of Rome.

Gazzillo, F., & Fiorenza, E. (2021b). Patient Scale of Couple Testing (PSCT) [Unpublished manuscript]. Sapienza University of Rome.

Gazzillo, F., Genova, F., Fedeli, F., Dazzi, N., Bush, M., Curtis, J. T., & Silberschatz, G. (2019). Patients’ unconscious testing activity in psychotherapy: A theoretical and empirical overview. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 36(2), 173–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/pap0000227

Gazzillo, F., Gorman, B., Bush, M., Silberschatz, G., Mazza, C., Faccini, F., Crisafulli, V., Alesiani, R., & De Luca, E. (2017). Reliability and validity of the Interpersonal Guilt Rating Scale-15: A new clinician-reporting tool for assessing interpersonal guilt according to control-mastery theory. Psychodynamic Psychiatry, 45, 362–384. https://doi.org/10.1521/pdps.2017.45.3.362

Gazzillo, F., Kealy, D., & Bush, M. (2022c). Patients’ tests and clinicians’ emotions: A clinical illustration. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 52(3), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-022-09535-w

Kealy, D., Treeby, M. S., & Rice, S. M. (2021). Shame, guilt, and suicidal thoughts: The interaction matters. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 60, 414–423. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12291

Lebow, J. L. (2019). Current issues in the practice of integrative couple and family therapy. Family Process, 58(3), 610–628. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.1247

Leonardi, J., Fimiani, R., Faccini, F., Gorman, B. S., Bush, M., & Gazzillo, F. (2020). An empirical investigation into pathological worry and rumination: Guilt, shame, depression and anxiety. Psychology Hub, 38, 31–42. https://doi.org/10.13133/2724-2943/17229

Leonardi, J., Gazzillo, F., Gorman, B. S., & Kealy, D. (2022). Understanding interpersonal guilt: Associations with attachment, altruism, and personality pathology. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 63(6), 573–580. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12854

Nielsen, A. C. (2019). Projective identification in couples. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 67(4), 593–624. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065119869942

Ringstrom, P. A. (2012). A relational intersubjective approach to conjoint treatment. International Journal of Psychoanalytic Self Psychology, 7(1), 85–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/15551024.2011.606642

Rodomonti, M., Crisafulli, V., Angrisani, S., De Luca, E., Mazzoni, S., & Gazzillo, F. (2022). Description and first steps toward the empirical validation of the plan formulation method for couples. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 52, 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-022-09534-x

Rodomonti, M., Crisafulli, V., Mazzoni, S., Curtis, J. T., & Gazzillo, F. (2019). The plan formulation method for couples. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 37(3), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1037/pap0000246

Silberschatz, G. (2005). Improving the yield of psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy Research, 27(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2015.1076202

Silberschatz, G., & Curtis, J. T. (1986). Clinical implications of research on brief dynamic psychotherapy II. How the therapist helps or hinders therapeutic progress. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 3(1), 27–37. https://doi.org/10.1037/0736-9735.3.1.27

Sprenkle, D. H., Davis, S. D., & Lebow, J. L. (2009). Common factors in couples and family therapy. The Guilford Press.

Weiss, J. (1993). How psychotherapy works. Guilford Press.

Weiss, J., Sampson, H., Zion, M., Psychotherapy Research Group. (1986). The psychoanalytic process: Theory, clinical observation, and empirical research. Guilford Press.

Zeitlin, D. J. (1991). Control-mastery theory in couples therapy. Family Therapy, 18, 201–203.

Ziegler, A., & Vens, M. (2010). Generalized estimating equations. Methods of Information in Medicine, 49(05), 421–425.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Specifically, the conceptualization and methodology were performed by FE and GF. Resources acquisition and supervision were performed by FG. Material preparation, data collection, and formal analysis were performed by the FE and GF. CV, CR, EDL, CDF, MLS, LJ, MC, RM, RL, and SM contributed to data acquisition and its subsequent interpretation. The first draft of the manuscript was written, reviewed, and edited by FE and GF, and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Department of Dynamic and Clinical Psychology, Sapienza University of Rome, Italy; Prot. n. 0001728 del 10/11/2021—[UOR: SI000092—Classif. VII/15].

Consent for Participants

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for Publication

The authors affirm that research participants signed informed consent forms for their data processing and publishing for research purposes.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Eleonora, F., Valeria, C., Renato, C. et al. Vicious Relational Circles and Chronic Couple Conflictuality: An Empirical Study. J Contemp Psychother 54, 155–162 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-023-09607-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-023-09607-5